Question: Question #1 about the case below 1) Perform an analysis of external opportunities and threats to Good Hands Healthcare given the information presented in the

Question #1 about the case below

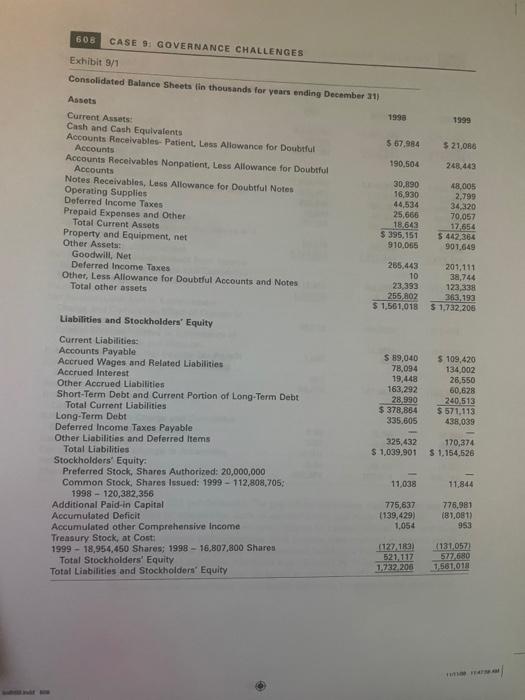

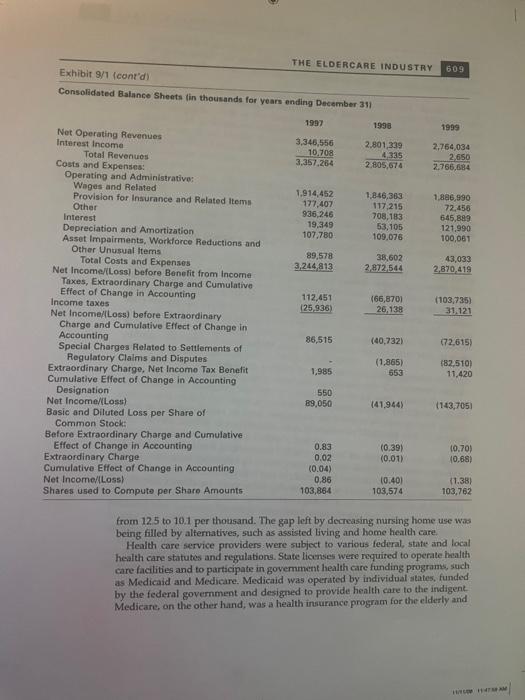

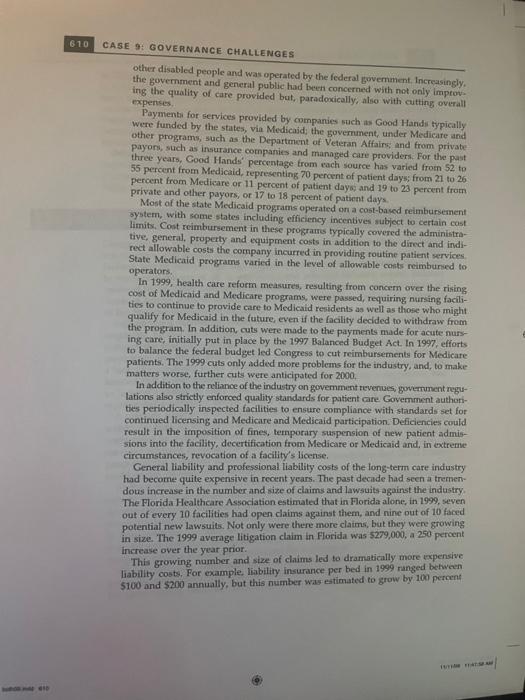

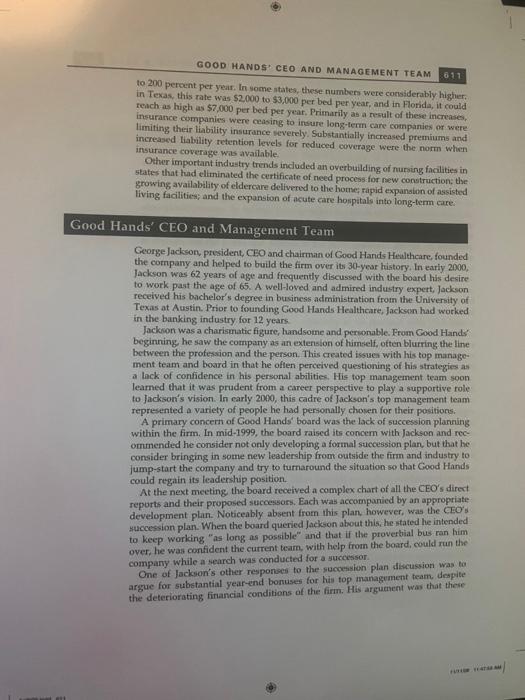

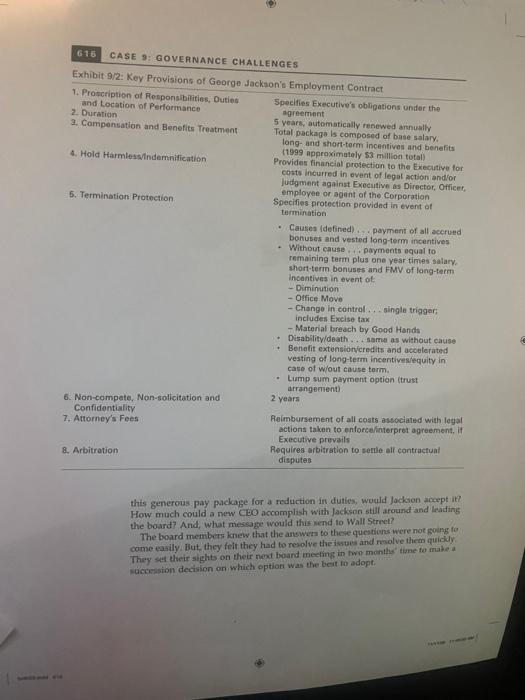

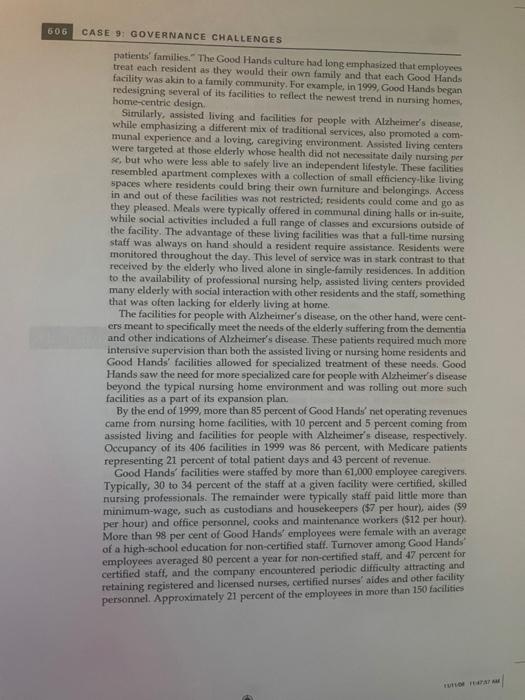

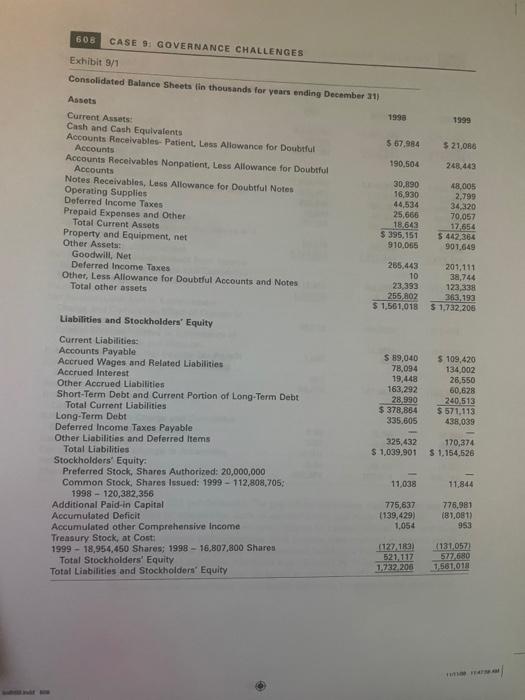

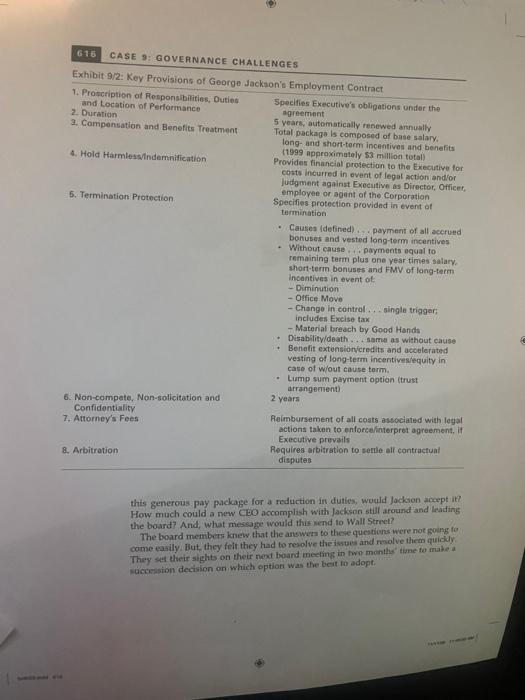

1) Perform an analysis of external opportunities and threats to Good Hands Healthcare given the information presented in the case. Report on all contributing factors. - Is Good Hands' performance slip primarily due to external, industry forces? - Do you feel that the elder care industry is attractive or unattractive? CAs 4 Governance Challenges at Good Hands Healtheare (A) In mid-2000, the board of directors of Good Hands Healthcare (Good Hands), a $3 billion company trading on the New York Stock Fichange, was pondering its current situationt It had becorne increisingly discouraged by the downward spiral of Good Hands" stock and financial performance and by the continuing explanations of the situation by the company's chief executive officer (CEO), George Jackson. Jackson, who had been Good Hand' CEO for the past 30 years, had attributed the slide of Good Hands' periormance to "external factors beyond our control" The health care industry was indeed subject to a great deal of envirormental factors, not the fenst of which was the reliance on government reimbursement for services. One of the major issues material far class discusion. The authors do not intend to lilustrate either elfective or incifective handling of a mansgerial witution. The atshon may have disguised eertain names and other identifying infoematine to protect confidentiality. lvey Management Servios prolitits any form of repreducticet lofage of: transmittal whehout iss writien permisinon. This material is not covered ander autharization from CenCopy or ary reprodocelon rifhts ofgantiation To eeder copies of mydest permlswion to ryproduce matrerithe eontad ivey Publivhing Ivey Management Services, c/o Riduard fvey 5chool of thasineis, The Univenily of Westem Ontario, Londor, Ontario, Canada N 6A 3X7; f hiane (519)66132015 : fax (519) 661-3892; e- nall casongivey awoca. Copyright o 2004. Ivey Manazenent Services facing the industry was significant reductions in federal funding of health and eldereare. In addition, the industry had experienced an increasing number of lawsuits filed by patients' families and attention by the media to incidents of poor care, especially of the elderly. Cood Hands, one of the largest US nuning home providers, was no exception to these lawsuits and, along with other indtestry players, was experiencing escalating patient care liability coste. The board of directors wondered, however, why Good Hands' major competitors, HealthUS, EderCare and Aged Services. Inci, were able to increase their protitability and market share at the same time that Good Hands' was stipping. After all, wasn't the whole industry affected by the same "external fictors"? Was there something else to explain Good Hands' recent troubles beyond these industry threats? In addition to questions regarding martagement's assessment of the firm's performance woes, the board of directors of Good Hands was concerned with the absence of a succession plan within the company. While Jackson was recognized as an industry leader, would he be able to stop the current dowrward spiral and perform a turnaround of the firm? And, if not, who would be able to step into his shoes? The lack of a succession plan at Good Hands coupled with no formal internal effort to develop leadership for the future cast an ominous shadow over the future of the company. The board knew it didn't have a lot of time to waste. Good Hands was sliding precipitously toward bankruptcy. In fact, several of its competitors had already filed Chapter 11, and as a result of their restructuring they were more nimble than Good Hands to weather the industry threats. The board set its sight on its next meeting, in two months, to address these important issues. All of the board members knew this meeting would be a critical turning point for the future of Good Hands. Good Hands Healthcare was founded as a small nursing home business in 1970 , in Browrisville, Texas. Through rapid expansion, the company went public in 1978 and now represented more than 400 facilities in 25 states. Good Hands operated facilities in three areas of operations: 285 nursing homes, 74 assisted living and outpatient ficilities, and 47 care units for people with Alzheimer's disease. George Jackson, the current CEO, had founded the business and had served as its president/CEO and chairman of the board for 30 years. While originally founded as a nursing home company, Good Hands diversified into assisted living and outpatient factlities in the early 1990 s and later, in 1995, into care facilities for people with Alzheimer's disease. Nursing home facilities now provided residents with long-term care, including daily skilled nursing and nutritional services, along with the social and recreational services that accompany a long-term residence facility. Pharmacy and medical supplies were also provided to residentr. Cood Hands saw themselves as an "extension of patients' families." The Good Hands culture had long umphasized that employees treat each resident as they would their own family and that each Cood Hands facility was akin to a family community. For example, in 1999, Good Hands began redesigning several of its facilities to reflect the neweit trend in nursing homes, home-centrie design. Similarly, assisted living and facilities for people with Alzheimer's disease, while emphasizing a different mix of traditional services, also promoted a communal experience and a loving, caregiving environment. Assisted living centen were targeted at those elderly whose health did not necessitate daily nursing per se, but who were less able to safely live an independent lifestyle. These facilitie resembled apartment complexes with a collection of small efficiency-like living spaces where residents could bring their own fumiture and belongings, Access in and out of these facilities was not restricted; retidents could come and go as they pleased. Meals were typtcally offered in communal dining halls or in-suite, while social activities included a full range of classes and excursions outside of the facility. The advantage of these living facilities was that a full-time nursing staff was always on hand should a resident require assistance. Residenbi. were monitored throughout the day. This level of service was in stark contrast to that received by the elderly who lived alone in single-farrily residences, in addition to the availability of professional nursing help, assisted living centen provided many elderly with social interaction with other reside The facilities for people with Alzheimer's disease, on the other hand, were centers meant to specifically meet the needs of the elderly suffering from the dementia and other indications of Alcheimer's disease. These patients required much more intensive supervision than both the assisted living of nursing home residents and Good Hands' facilities allowed for specialized treatment of these needs. Good Hands saw the need for more specialized care for people with Alzheimer's disease beyond the typical nursing home environment and was rolling out more such facilities as a part of its expansion plan. By the end of 1999 , more than 85 percent of Good Hands' net operating revenues came from nursing home facilities, with 10 percent and 5 percent coming from assisted living and facilities for people with Alzheimer's disease, respectively. Occupancy of its 406 facilities in 1999 was 86 percent, with Medicare patients representing 21 percent of total patient days and 43 percent of revenue. Good Hands' facilities were staffed by more than 61,000 employee caregivers, Typically, 30 to 34 percent of the staff at a given facility were certified, skilled nursing professionals. The remainder were typically staff paid little more than minimum-wage, such as custodians and housekeepers $7 per hour), aides (\$9 per hour) and office personnel, cooks and maintenance workers ( $12 per hour). More than 98 per cent of Good Hands' employees were female with an average of a hugh-school education for non-certified staff. Tumpver among Good Hands employees avenged 80 percent a year for non-certified staff, and 47 percent for certified staff, and the company encountered periodic difficulty aftracting and retaining registered and licensed nurses, certified nurses' aides and other facility personnel. Approximately 21 percent of the employees in more than 150 facilities were represented by various labor unions, the largest of which was the AFL-CEO While relations. with these unions had bein generally good (Good Hands had not experienced any wctric stoppages as a result). the unions had comtmonly targeted Good Hiands because of its visible position as one of thet largest companics in the US eidercare industry. Good Hands' financial position had deferivrated in the last there years (sce Faxhibet. 9/1). Most notably, for each of the previous three years, Good Hisnds had experienced declining sales growth and net income. In 1999 , this low was 103 percent. in sales from the previous year and a loss of $143.7 million in net income. Its competitors' expericnces in recent years were much more fobust. HealthUs grew sales from 1998 to 1999 by 442 percent despite a drop of 33 percent in het incorne. while ElderCare's oneyear sales growth was 5.7 percent with a 90,7 percent increase in net income. Aged Services, Ine, posted an 8 percent loss in sales over: the previous year, but had a total net income of more than $1 billion. As a result of Good Hands' declining performance, the company was in a crition cash position, with cash at the end of 1999 of only 521 million. The funds needed to sustain its business were provided largely through revolving credit that increased overall short-term borrowing to $173 million. Total debt, on and off balance sheet. had grown by sarly 2000 to nearly $1 billion, and, along with it, the cost of debt for Good Hands had also risen considerably. This put Good Hands at a substantial disadvantage pis-dewis its major coinpetitors. Health Ws and Aged Services, Inc.e Who as a result of coming oth of Chapter 11 bankruptcy had restractured their debt and were much less encumbered than Good Hands. Eldercare Industry Health care and general care for the elderly was a highly regulated industry and a fragmented industry with a significant number of "mom and pop" facilities. While Good Hands Healthcare was one of the fargest companies in the industry, and they had the largest share of the nursing home market, this only represented 3.8 percent of the market. It was estimated that in the also very fragmented assisted-living industry, the top 25 players accounted for only 2 to 5 percent of the market. The leader in the home health care industry, Sultivan Servicesi. similarly. had only 4 percent of the market. Increasing life expectancies and aging baby boomers were driving US revenues for long-term health care. US revenues for long-term health care were estimated to total $225.8 billion by 2003, versus $149.4 billion in 1998 . Revenues for nursing homes were expected to rise to $115.4 billion in 2003 , versus $S7.3 billion in 1998 when home-care reventes were expected to rise to $48.7 billion from $33.2 bitlion. Despite the healthy forecasts for growth in revenue, the 1995 National Nursing Home Survey suggested that elderly Americans were reducing their use of nursing home care. The chariges from 1985 to 1995 per thousand elderly are illustrntive. In 1985,219.4 per thousand elderly aged 65 to 74 uved nuring homes whereas by 1995, this number dropped to 198.6 per thousand. For ages 75 to 35 this number dropped from 575 per thousand to 45.9 per thousand, and for ages 85 and older, Consolidated Balance Sheeta fin thousanda fac Consofidated Balance Sheets tin thousands for years ending December 311 from 12.5 to 10.1 per thousand. The gap left by decreasing nursing home use was being filled by alternatives, such as assisted living and home health care. Health care service providers were subject to various federal, state and local health care statutes and regulations. State licunses were required to operate halth care facilities and to participate in government health care funding programs, such. as Medicaid and Medicare. Medicaid was operated by individual states, funded by the federal government and designed to provide health care to the indigent. Medicare, an the other hand; was a health insurance program for the elderly and othiz disabled people and was operated by the federal govemment. Increasingly. the govermment and general public had been concerned with not only imptov. ing the quality of care provided but, paradoxically, also with cutting overall expenses. Paymenti for services provided by companies such as Good Hands typically were funded by the states, vin Medicaid; the government, under Medicare and other programs, such as the Department of Veteran Affains and from private payors, such as insurance companies and managed care providers. For the past three years, Good Hands percentage trom each source has varied froen 52 to 55 percent from Medicaid, representing 70 percent of patient days; from 21 to 26 percent from Medicare or 11 percent of patient daywa and 19 to 23 percent from private and other payors, or 17 to 18 percent of patient days. Most of the state Medicaid programs operated on a cost-based reimbursement system, with some states including efficiency incentives subjoct to certain cost limits, Cost reimbursement in these programs typically covered the administrative, general, property and equipment costs in addition to the direct and indirect allowable costs the company incurred in providing toutine patient services. State Medicaid programs varied in the level of allowable conts reimbursed to operators. In 1999, health care reform measures, resulting from concern over the rising cost of Medicaid and Medicare programs, were passed, requiring nursing facilities to continue to provide care to Medicaid residents as well as those who might qualify for Medicaid in the future, even if the facility decided to withdraw from the program. In addition, cats were made to the payments made for acute nursing care, initially put in place by the 1997 Balanced Budget Act. In 1997, efforts to balance the federal budget led Congress to cut reimbursements for Medicare patients. The 1999 cuts only added more problems for the industry, and, to make malters worse, further cuts were anticipated for 2000, In addition to the reliance of the industry on govemment revenises, government negulations also strietly enforced quality standards for patient care. Govemment authorfties periodically inspected facilities to ensure compliance with standards set for continued licensing and Medicare and Medicaid participation. Deficiencies could result in the imposition of fines, ternporary suspension of new patient admissions into the facility, decertification from Medicare or Medicaid and, in extreme circumstances, revocation of a facility's license. General liability and professional liability costs of the fong-term care industry had become quite expensive in recent years. The past decade had seen a trernendous increase in the number and size of claims and lawsuits against the industry. The Florida Healthcare Association estimated that in Florida alone, in 1999, seven out of every 10 facilities had open claims against them, and nine out of 10 faced potential new lawsuits. Not only were there more claims, but they were growing in size. The 1999 average litigation claim in Florida was $279,000, a 250 percent increase over the year prior. This growing number and size of claims led to dramatically more ixpensive liability costs, For example, liability insurance per bed in 1999 ranged between $100 and $200 annually, but this number was estimated to grow by 100 percent to 200 peroent per year. In some ntates, these number were considerably higher, in Texas, this rate was $2,000 to $3,000 per bed per year, and in Florida, it could reach-as high as $7,000 per bed per year. Primarily as a result of these increases, insurance companies were ceasing to insure long-term care companies or were limiting their liability insurance severely. Substantially increased premiums and increased tiability retention levels for reduced coverage were the norm when insurance coverage was available. Other important industry trends induded an overbuilding of nursing facilities in 5 ates that hud eliminated the certificate of need process for new convtruction; the growing availability of eldercare delivered to the home; rapid expanaion of assisted fiving facilities; and the expanston of acute care hospitals into long-term care: Hands' CEO and Management Team George Jackson, president, CEO and chairman of Good Hands Healthcare founded the company and helped to build the firm over its 30 -year history, In eariy 2000 , Jackson was 62 years of age and frequently discussed with the board his desire to work past the age of 65 . A well-loved and admired industry expert, Jockson received his bachelor's degree in business administration from the University of Texas at Austin. Prior to founding Good Hands Healthcare, Jacksen had worked in the banking industry for 12 years Jackion was a charismatic figure, handsome and perwonable. From Good Hands' beginning, he saw the company as an extension of himself, otten blurring the line between the protession and the person. This created issues with his top management team and board in that he often perceived questioning of his strategies as a lack of confidence in his personal abilities. His top management team soon learned that it was prudent from a career perspective to play a supportive role to Jackson's vision. In carly 2000 , this cadre of Jackson's top management team represented a variety of people he had personally chosen for their positions: A primary concern of Good Hands' board was the lack of succession planning within the firm. In mid-1999, the board raised its concern with Jackson and recommended he consider not only developing a formal succession plan, but that he consider bringing in some new leaderahip from outside the firm and industry to jump-start the company and try to turnaround the situation so that Good Hands could regain its leadership position. At the next meeting the board received a complex chart of all the CEO's direct reports and their proposed successors. Each was accompanied by an appropriate development plan. Noticeably absent from this plan, however, was the CEO's succession plan. When the board queried Jackson about this, he stated he intended to keep working "as long as possible" and that if the proverbial bus ran him over. he was confident the current team, with help from the board, could run the company while a rearch was conducted for a successor. One of Jackson's other responses to the succession plan discussion was to argue for substantial year-end bonuses for his top management team. despite the deteriorating financial conditions of the firm. His argument was that these needed to retain them. would also be appropriate although he did not go so in his own compensation. Chief Jinancial Orficer (CFO) Bob. Waymot go so far as to threaten to quit 1976. Wayman had experience with a Wall Street investrnent company prict to 1976. Wayman had experience with a Wall Street investment company prior to ness administration from Minnesota Seate Univeraity. A high's degree in buajextremely competitive person, especially with Chief Legal Coursel David Baker the board was concerned that Wayman lacked the personality to be an effective leader. Wayman frequently commented that the numbers were the heart of the business. On multiple occasions, the board had questioned Wayman's ability to strategically manage the balance sheet to reflect the needs of the cash flow situatian The board questioned whether he was "old school" cautious since he refused to The baard questioned whether he was "old school cautious since he refused to to smooth out the peaks and valleys in the reimbursement stream. In addition. when asked questions by the board on routine financial issues, he tended to be defensive and often treated the question as if it were stupid. Another issue that arose with some frequency was that he did not see his role as reporting to the board's Audit Committee and often circumvented the committee to resolve an issue with the CEO without bringing it to the board's attention. However, the marked lack of financial expertfse among the rest of the senior management team had made him indispensable to the CEO, especially in his dealings with Wall Street. Chief Operating Officer (COO) Jarnes O'Malley (age 6:d) joined Good Hands in 1987 after working for a competitor in the health care industry for eight years. Since: that time, OMalley had risen up the ranks of Good Hands through the operations division and, in 1990, was appointed both COO and a member of the board of directors. While O'Malley was well liked and respected throughout the company. he was nearing retirement and was not likely to continue employment with Good Hands for more than another year or two. O'Malley was also well liked by the board but had been questioned frequently about his resistance to making changes to the operating model. His responses wete typically a stream of explanations and excuses, mostly attributable, in his estimation, to "causes outside his control." However, given the quality-of-care issues and the difficulty finding more quertioning of his effectiveness. Chuef Legal Counsel (CLO) David Baker (age 54) was a close confidant of Jackson. The two of them were social acquaintances before Jackson persuaded Baker to leave his law firm to become in-house counsel for Cood Hands in 1989. Baker often played the role of smoothing over the CEO's behavior when it was questioned by the board, and he was quick to defend Jackson's actions. While Haker was an accomplished attorney and had valuable expertise in the health care arena, he lacked any management experience beyond the legal areas of the business. The board commonly regarded him as "a thorn in their side" and often questioned his handling of legal maiters. His exclusive use of orly one outside law firm regardes of the matter, had caused many late-night discussions among board inemben. The board's concern over his competence had been discussed with the CEO in meral ececutive sessions and had become a point of contention between the board and the CEO, who ardently defended his friend, Bakie had also been the bey person to structure all of the employment contracts of the senior ruragement team and was, therefore, held in high regard by his peen in the company. Hands' Board Good Hands Healthcare's board was composed of 10 members total: eight outsidemembers with varied lengths of tenure and two inside members, Good Hands CEO and Chair George Jackson and 800 James OMMalley. Five of the board members had been on the board since it was founded and were handpicked by Jackson. The three newer members joined the board within months of each other in 1998 when the existing board realized that there were too few members to effectively handle all of the board committees. When there were only five indes pendent directors, they found they were all attending every committee meeting and, as a result, they were either devoting too much or not enough time to the issues at hand. Not wanting to be remiss, they decided that the addition of three new members, each with the ability to chair one of the committees, wouId be the appropriate number. They hired a search firm and recruited three directors within one year of beginning the search. Since adding the last three members to the board, no new directors had been added. The board diseussed frequently the need for "new ideas and diversity" but had made no progress in replacing the more senjor directors. Howard Learned was the dean of the School of Business at Minnesota State University. He was 62 years old and had been on the board for nine terms of three years each. He was a professor of business when the CFO of the company was in business school getting an MBA. When the company went public and was recuiting a board, the CFO thought of his old professor. Learned brought good experience and knowledge to the board and added the prestige of having a business schood dean on the board. Learned had chaired a number of committees over his board tenure, but, perhaps most importantly, he had daired the Compensation Committee for the past 20 years. He also had served on the local board of a national bank Steven Scales was 60 years old, from a small town near the corporate headquarters and was the managing partner of asmall law firm. He was known to the former CEO through years of golfing together, and his wife and the CEOr wife had been longtime friends. Steven Scales legal knowledge had been essential in keeping Good Hands in regulatory compliance as they grew. Scales had chaired the Governance Commitree, the Nominating Committee and the Audit Conmitter over his terms as a director. He did not serve on any other public board but wan active on many civic boards in his commurity. Norm Current, age 61, was a banker from Brownsville. Teas, where the curporation was founded. Although the corporate headquarten had ince relocated, Current decided to stay on and maintained an excellent contact base amons employve and legislaton. He had chaired the Compensition and Audit Conmitferi during: his tenure and was a closet, personal friend of the CBO. Hi behavior in board. He eicher cuntributed very unpredictable and he tended to be somewhat volatile. He either cuntributed very little or contributed on issues he felt strongly about in an aggressive fashion, using terms that were sometimes inapproptiate in the of the community hospital. of the commurity hospital. Don Ansan is 63 years old, an attorney and a former US congressman. He had been friends with Jackson since college. They frequently went on fishing trips, hunting trips and vacations together with their wives, His national clout had been an important factor in getting things done in Washington in a highly regulated industry. He had chaired the Nominating Committee for most of the years he was on the board and also had chaired the Compensation Committee for several years. He was active in national polition and, since his retirement from Congreso, served on the bourds of various political organizations. Frank Fowler, age 61, was an investment banker whose company did the earlest financing of Cood Hands. Fowler's company also took the company public and held a significant position of Cood Hands stock. He and Jackson had been hunting buddies for many years. Fowler was probably the board member who Was the closest business advisor/confidant of the CEO. He served on the boards of various comparies that his company had financed. The three newer members of the board had been recruited by executive search firms and had no prior relationship with aryone on the board or on the management team. Gerry Comco, age 62, was the retired CEO of a telecommunications company and lived in Boca Raton, Florida. He had been recruited during the time when the board was discursing a change to its strategy and wanted additional "out of industry" perspective. Comco was aggressive and outspoken, respected and liked by the rest of the board. He had recently been named chair of the Governance Committee and undertook a thorough review of the committee charters, calendars and board composition. Prior to leaving his company, he had served on its board of directors. Mark Andrews was 58 years old, and was the senior vice-president (SVP) of a global company. This was his firnt experience on a public board but his profes. sional background frade him an excellent board member. He was well liked and spoke up about the most important issues. He had particalar expertise in operations and could make some significant contributions as the company expanded its operating model beyond nursing home operations. He was the charman of the Compensation Committee and had initiated an exhaustive review of the company's compersation policies and philosophy upon accepting the chairmanship. He served on the board of one of the subsidiaries of his company and was a competitive athlefe. Gieg Simon, age 59 , was a consultant, a former banker and presidential appointee to the board of a national regulatory agency. He was also an expert in the areas of corporate govemance, strategy and risk. He had been asked to chair the Nominating Committee shortly after joining the board. In this capacity he had intitiated a formal process for evaluating the board and CFO. He nat on the boards of four pukie companist, Good Hands" board of directors knew the company was at a crossroads. Was the industry environment really the cause of Good Hands' sliding financial performance? What strategies would be necessary to stop the slide and regain Good Hands' dominant position? How would Good Hands weather the changing regulatory climate and reimbursement cuts? These were among many questions that the board knew had to be addressed to keep the company affoat and to ensure its survival as a viable entity in the future. But, perhaps more pragmatically, was Jackson still the best CEO to lead Good Hands? Did he have the management team in place that could help chart a new course for the future? If not, who would take Jackson's place? The board saw three primary alternatives, First, they could keep Jackson on as CEOand see how Good Hands fared in the coming months. But, could they continue to do so in light of the company's precarious financial position? Jackson had grown the company to its heights but also had presided over its recent decline. Had conditions changed so much that a new leader was needed? Most pragmatically, keeping Jackson in place would be the lowest cost option due to the nature of his employment contract. In 1997, the board (then consisting of Learned, Scales, Current, Anson and Fowler) had approved an employment contract for Jackson that would grant him in excess of $25 million (including severance, salary, options, benefits, etc.) if he were removed from his position as CEO (see Exhibit 9/2). Second, the board could ask for Jackson's resignation and underiake a search for his replacement. Asking lackson, the company's founder and leader for more than 30 years, to step down would be no easy task. if he ieft Good Hands, what would be the effect on the culture? How would the company make up for the payments when the company was already short on cash? Would they find a payments when the company was already short on cash? Would they find a need to look outside the company and/or industry? On the one hand, promoting from within would minimize the lack of additional losses in the top management team who may resign if they are overlooked for promotion. And, continuity in experience, strategy, etc. would be achieved by promotion within. On the other hand, was the board satisfied that any of the current top management team could tackle the job and work well with them? Going outside could bring in some fresh perspectives that may be much needed as well as one potentially improving Good Hands' competitiveness via the insights into other company's best practices and operating models. Finally, the board saw a compromise position. Could they ask Jackson to give. up his position as CEO yet stay on as chairman of the board? This option would be much easier than a total resignation and overcome the Joss of ls expertise, etc. Under this option the board expected to keep Jackson's current compensation package, which totaled just over $3 million annually, intact but they would not be liable for any additional compensation because such a move would not trigger any additional severance under the terms of his agreement. But even at this generous pay package for a reduction in duties, would Jackson accept it? How much could a new CEO accomplish with Jackson still around and leading the board? And, what mesogge would this nend to Wall Strect? The board membetn knew that the astswers to the qe questions were not going fo come easily. But, thcy feit they had to resolve the issues and ruolve them quiclly. They set their sights on their rient board meeting in fwo menths time to mahe a succersion decision or which option was the beit to adopt

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

1 Expert Approved Answer

Step: 1 Unlock

Question Has Been Solved by an Expert!

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts

Step: 2 Unlock

Step: 3 Unlock