Question: QUESTION, 1) Identify the personnel interviewed in the case study and construct an organizational chart. 2)Based on the interview with Mr. Doit (and any other

QUESTION,

1) Identify the personnel interviewed in the case study and construct an organizational chart.

2)Based on the interview with Mr. Doit (and any other information you can find in the case study), use Microsoft Visio to create process maps for the following:

i. Production of plastic products

ii. . Production of metal products

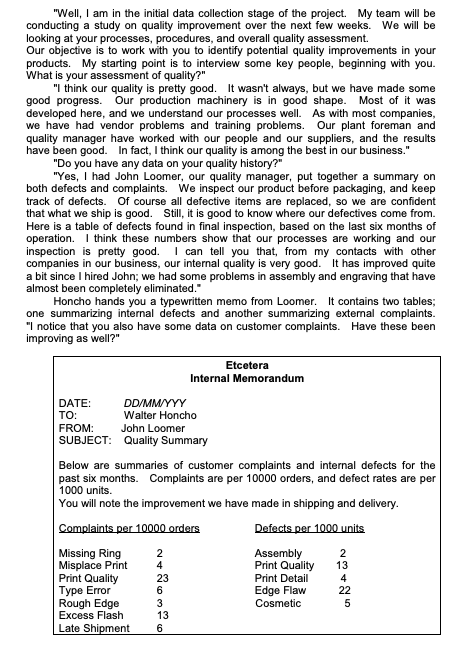

2.1 Irving Magnate, President Irving Magnate has been with the company since its formation. He worked for his father, Theodore Roosevelt Magnate (known as "Old T. R."), in Magnate Stampings in various capacities for 25 years. When Etcetera was formed, Irving was company controller and Old T. R. was president and CEO. Irving became president at Old T. R.'s retirement ten years ago. Irving Magnate is also the ownership spokesman; the other family owners are involved in other enterprises (some are retired), and leave the operation of Etcetera to Irving. For all practical purposes, Irving Magnate is authorized to make all decisions, including reorganization of the company. Irving's style of management could best be described as "enlightened paternalism". He thinks of himself as a surrogate father to the employees, and these feelings are reciprocated. He is very concerned about the fate of the company and its employees after his retirement, and this has led him to investigate reorganization into an employee-owned enterprise. He has read extensively on issues in quality, and recently attended a seminar presented by a well-known consultant. He has come to the conclusion that quality is the key to retaining market in an environment that is potentially more competitive that what now exists. Being both open-minded and conservative (not necessarily a contradiction), he is receptive to change, but wants it justified and a new stability reached before reorganization. The meeting takes place in Irving Magnate's office at the plant. He offers you coffee, and engages in casual conversation while he serves it. Upon returning to his desk, however, he becomes all business, and asks "Where do we start?" "Mr. Magnate, I want to begin by asking about your commitment to this process one last time. The likelihood is that our study will result in changes being made, both short-term and long-term. The study itself will be disruptive to some extent, and we should not start unless you are fully committed and your employees will understand and accept what we are doing. Starting this job and then stopping it short could be worse than doing nothing. Are you fully committed, and have you communicated your commitment to the company?" "First, please call me Irving. We are like a family here. You have a better parking place than I do because visitors park near the lobby, and all employees, including me, park in the lot first come first served. But to answer your question, I am fully committed. From what I have read and heard, I think I understand the importance of my commitment. I appreciate your bringing up some possible negatives, but I believe they are worth the risk. I have discussed this with the VP of Manufacturing and the Quality Manager, and we would like to defer notifying the rest of the company until we can tell them more about what to expect. I would like for you to tell me that as soon as you can." "Fine. I would like to talk to a few of your people today, and I can tell you what to expect by the end of the day." "All right. I will draft an announcement with your help, and have it distributed tomorrow. Now, how else can I help you?" "I would like to get a feel for your current status, and I would like to start with an overview of the situation. What is your assessment of current product quality?" "Our quality is very good, probably the best in the business. We hired a quality manager five years ago, and he has done an excellent job. He installed a quality audit system, and then trained some key people in quality, SPC, things like that. I think we had to hire a few inspectors, but the investment has been worth it. I am not so concerned about present quality as keeping ahead of our competitors." "How conscious are your workers of quality concerns?" "They are very aware of its importance. Every worker knows about our 'Do it right the first time' philosophy. We have a suggestion program, and a quarterly quality newsletter recognizing our best workers. In fact, your study here will fit right in with what we have been doing." "Are your suppliers involved in your quality program?" "No, and that is an occasional problem. We have had to step up our incoming inspections. Our suppliers know that if we get bad material, we send it back. Their contracts require replacement of bad material at no cost, so they are usually pretty good." "Are you concerned about quality costs?" "Well, yes, to the extent that I am concerned about all costs. Our quality costs have gone up a little through hiring of inspectors, and I have hired you, so you know I think of it as an investment. We don't get a lot of returned goods because we don't ship a lot of scrap. Our people know I won't tolerate shoddy work; quality has always been part of our reputation." "How much of an investment in time are you willing to make in improvement? In other words, how soon do you expect results from this study?" "I know better than to expect instantaneous results. I also know that longterm change takes a long time to accomplish. You told me your study would be complete within a month, and I expect some concrete recommendations from it. Getting that in place, though, is another matter. I expect major changes to take up to a couple of years to show results, but I hope we can make some headway in some areas sooner than that." "That's good. I wanted to be sure you were not expecting miracles. All the people involved, but most especially the management, need to understand, and accept, that lasting improvement means changing the processes. This invariably leads to someone's duties being changed, more responsibility given to the workers, and a perceived dilution of management's authority. These things don't happen overnight." "I'm not sure what you have in mind on dilution of management's authority." "Well, I start with the assumption that you have good workers and good managers, but they don't necessarily understand that what is best for a single department might not be best for the company. Some companies have management systems that guarantee that individual departments optimize their operations at the overall cost of the company. We have what appears to be a fundamental contradiction. We would like to free the workers and managers of constraints that limit how well they do their jobs, but central authority or management gets in the way. If we proceed to give workers more authority, this dilutes management authority, and it seems to mean that individuals, not departments, might optimize their own work at the cost of the overall company. To coordinate these efforts, we need a system of operation that lets each person know his or her role in the organization, not just the position title and reporting requirement. If all of your people are well trained, understand their roles, and work in an environment that fosters cooperation to achieve common goals, you have that system of operation. Of course that is a much simplified description of it." "And you are going to do this in a month?" "That's the key point. In a month, we can identify some process problems that can probably be profitably improved in the short term. The training, reaching a new level of understanding, and creating the environment to keep the system going can take a long time." "Is this the 'change in corporate culture' that I have read about?" "Yes, it is. And this is the most difficult part of improvement to achieve. You hear terms such as 'cultural change', 'transformation', and 'continuous improvement'. They all mean essentially the same thing. You eventually have to change the way you do business within the company to a mode and style that not just allows, but encourages all of your employees to participate in continuous improvement. The cultural change or transformation is what is necessary to get to this stage. And it is you and your management who will be most affected by it. Some of this change can be accomplished simply through correct training of workers and management, to give them the tools to do the job. But a large part of it is the acceptance by the management that the transformation is necessary." "I see why you are concerned about commitment. I probably have some managers who will have trouble accepting all of this." "I would be surprised if you did not. This acceptance will really be your job, not mine. I can help some, with training slanted especially for your managers, and with some good examples of successful companies who are in this transformation. You can't simply copy what they do, because the system you end up with should be developed with your own needs and environment in mind. This means the system will be created by your people, with some coaching and help." "Should we send some managers to visit Japan, and see what they are doing?" "Not right away and possibly not at all. I think it is a mistake to think in terms of Japanese methods. Many of the things that need to be done are common sense; they are difficult sometimes because they seem to be contradicted by what we have been taught and how we have practiced for years. We have the Japanese example to show us that what we have been taught is not necessarily right. But the methods the Japanese used are not uniquely Japanese. They had the benefit of some good teaching and coaching, from Deming and Juran, beginning in the 1950's. But they didn't succeed simply because they are Japanese, and they didn't succeed in a short time. As a country, they took about 20 years. Some companies developed much quicker, and continue to improve. The secret of their success was the way they used the training and coaching they got, with their commitment to improvement over the long term. They use their management methods in American plants with American workers, and are successful here, too. It is this kind of commitment that I mean when I ask if you are committed. It is recognition that, without this transformation, you are limited to short-term fixes that may be profitable in the short run, but do nothing to affect long term operations. My team is going to begin with short-term problems, but you need to be taking a longer view." "Well, now I understand better why you asked about my commitment, and I can see how this might be more disruptive to management than the workers. I must tell you that I have some reservations. I will need to be convinced before we go beyond the process improvements we have talked about. I am still committed to your study, but what you are talking about is a major change in the company." "That's right, it certainly is. Let us do this. I will begin the study, and you can announce to your employees that my team will be conducting a monthlong quality improvement study. During the course of the study, you will have opportunities to see what we are doing, and how we are doing it. This will show you what kind of training your line workers will need, because they should learn to do the same kinds of studies on their own. In the later stages of the study, I will want your management to participate in some sessions leading to development of a strategy for quality improvement in your company. This will address more longterm issues. At the end of the study, you will have seen the methods we use and the results we have gotten, and I will give you a set of recommendations for further action. At that point, we can discuss all this again. So, you have some options, and part of my job will be to give you information to use in selecting options." "That sounds fine. At the very least, you might discover some process improvements that we can use. What do we do next?" "I would like to talk with a few of your managers and employees. If you will introduce me to your VP of Manufacturing, I will start getting into details." 2.2 Walter Honcho, VP-Manufacturing Walter Honcho has been with Etcetera for ten years. He was hired in his present position from a position as senior manufacturing engineer. Walter is a mechanical engineer by education, and has an MBA that he earned part-time while working several years ago. He is in his late 40's, and appears to be in good physical condition. A potentially significant fact is that Walter Honcho was responsible for the design of much of Etcetera's production processes; he may take suggestions for improvement as implied criticisms of his design. His office is down the hall from Irving Magnate's, nearer the production area. Irving Magnate introduces you to Walter Honcho in his office. It is clear from the introduction that Magnate and Honcho have discussed the purpose of the visit. Magnate leaves, Honcho returns to his desk, and you take a seat across from him. Honcho begins by asking "How can I help you in your project?" "Well, I am in the initial data collection stage of the project. My team will be conducting a study on quality improvement over the next few weeks. We will be looking at your processes, procedures, and overall quality assessment. Our objective is to work with you to identify potential quality improvements in your products. My starting point is to interview some key people, beginning with you. What is your assessment of quality?" "I think our quality is pretty good. It wasn't always, but we have made some good progress. Our production machinery is in good shape. Most of it was developed here, and we understand our processes well. As with most companies, we have had vendor problems and training problems. Our plant foreman and quality manager have worked with our people and our suppliers, and the results have been good. In fact, I think our quality is among the best in our business." "Do you have any data on your quality history?" "Yes, I had John Loomer, our quality manager, put together a summary on both defects and complaints. We inspect our product before packaging, and keep track of defects. Of course all defective items are replaced, so we are confident that what we ship is good. Still, it is good to know where our defectives come from. Here is a table of defects found in final inspection, based on the last six months of operation. I think these numbers show that our processes are working and our inspection is pretty good. I can tell you that, from my contacts with other companies in our business, our internal quality is very good. It has improved quite a bit since I hired John; we had some problems in assembly and engraving that have almost been completely eliminated." Honcho hands you a typewritten memo from Loomer. It contains two tables; one summarizing internal defects and another summarizing external complaints. "I notice that you also have some data on customer complaints. Have these been improving as well?" "Yes, but not as much. Of course customers don't always look for the same things that we do, and as our costs increased a little we found that customers got a little more 'picky'. Still, we have improved there, especially in our counts and shipping dates. Our process related quality has been perceived as very good by our customers, but we have had to work on shipping and delivery. I worked with Fred Doit, the plant foreman, on some production control problems to help those problems." "I would appreciate having a copy of this, if I may." "You can keep that one." "Thank you. I appreciate the background I have gotten from you and Mr. Magnate, and with your permission I would like to continue my interviews. You mentioned Mr. Doit and Mr. Loomer; I would certainly like to talk to them. I would also like to speak with some experienced line workers." "There are two people you should talk to. Edith Scriptus is a lead engraver. She supervises our custom product section, and has a very good working knowledge of input processes in both plastics and metal. Our most experienced press operator is Jim Bob Twister. He has been with us for a long time, and has the best knowledge of our press and die operations in the plant. I will call ahead and tell them to expect you, if that would help." "Yes, it would. I would also like one additional favor. If you have an empty or idle office where I can leave my briefcase and work on notes without getting in anyone's way, I would appreciate using it." "There is an empty conference room just down the hall. If you don't have any more questions, I can take you there." "Thanks. I appreciate your time. I might need to clarify some points later, but you have helped a great deal already." Honcho takes you to the conference room and leaves you there. While he is calling the remaining interview contacts, you take out a notebook to make some notes on the interviews so far. In interviewing the top two people in the organization, one objective was to assess the level of commitment and understanding about quality. Another was to try to determine just how knowledgeable they were about operational problems. These interviews may also help guide the development of questions for other interviews. Finally, as a matter of courtesy, Magnate and Honcho should be informed of other interviews, and ideally would cooperate in identifying people to interview. 2.3 Fred Doit, Plant Foreman The plant foreman is the chief line worker at Etcetera. He manages and supervises all operations, and reports to Walter Honcho. Fred Doit has been with the company for several years. He has been trained as a machinist and machine operator, and has a two-year degree from a local tech school. While his theoretical knowledge of production problems might be slim, his working knowledge of the production system is excellent. You meet Mr. Doit after calling for an appointment, and arranging to meet at the production floor entrance from the executive offices. While he has an office, Fred spends much of his time on the floor, and your interview will be conducted as he gives you a tour of the system. Fred provides you with safety glasses and a lab coat. He tells you that this is one of his daily tours of the facility, and he will combine his tour with an orientation, if you don't mind his stopping to talk with operators along the tour. You ask his permission to record the tour on your pocket recorder, and he agrees. (Since Fred is about to give you information about the basic operation of the system, you want to be sure not to miss any critical steps in the process.) The tour begins as you walk toward a material storage area. "We are starting at the beginning of the processes for both the plastic and metal products. Both processes are mostly straight-line, with plastic on your left and metal on your right. The processes are similar except for the different materials. We store plastic chips, plastic coloring, and coils of mild steel and brass at this end; they are delivered in bulk from the receiving dock. The plastic chips are the basic material for the plastic tags, and we add coloring according to customer order. These are measured into a molding machine, with a die set for the size and shape we are running. On the other side, we feed metal coil into a press, where dies stamp out the metal tags." "Is there much difference between the metal and plastic tags?" "No, almost all of our products are standard size and shape, in both plastic and metal. We keep die sets for all the standard products, and have to have different sets for brass and steel. The machines are basically standard, except that we have modified the feed and output to fit our system. Plastics feed onto a conveyor into the trim machine, where we take off rough edges and square up the tag. It isn't really flashing, but we call it that. On the metal side, the tags come out in finished shape and size, and we send them through a finish operation, usually anodizing or just polishing. We used to have a problem with metal tag damage on the conveyor, but we changed the belt material and speed, and that cleared it up." "Are the cycle times about the same on both lines?" "Yes, they are pretty well balanced. Some finish operations take a little longer on the metal, but they are done in batches, while the plastics are one-at-a-time, so it balances out. After trimming, the plastics go into a stamping machine. A die puts whatever symbol or standard text the customer ordered into the plastic. On the other side the same thing happens to metal tags in a press. Some metal tags go into an ink-stamping machine instead." "The ink-stamping machine looks newer than the rest." "Yes, it is. Customers are ordering more metal tags with smooth surface and ink stamping, because we can put on more symbols at less cost. It is the same as engraving plaques at a jeweler's or sporting goods store. More people buy the smooth finish than the old-fashioned engraving. That is a pretty nice machine. We can change the symbol or text in a matter of minutes, and it has taken some load off the custom engraving section. That's the next stop. Standard tags go straight to assembly on conveyors to the press or stamping, but custom jobs go to engraving. That is mostly plastic now." "That gives you cleaner operations, doesn't it?" "Much cleaner than when we had metal chips all over. It is a lot easier to clean up around a plastic engraver. Edith, here, has been around through all these changes, and likes it a lot better now." You stop to talk with Edith Scriptus, lead engraver. After she talks with Doit, you make an appointment to speak with her later. "All tags go through assembly. All we do here is attach a metal ring. The machine is automatic, and the ringwire feeds off a coil, gets wrapped through the hole, and is cut off. Very little problem with this machine, but it misses a tag now and then. Next stop is inspection. Hello, John." John Loomer is in the inspection area talking to an inspector. He is the QC manager, and has been told by Honcho that you want to talk to him. You make an appointment for a later meeting. "Last stop is packaging. We have standard packages for all tags, with labels cut from the same order that started the batch. Most batches are shipped within 24 hours of packaging." "It seems to be a smoothly running system. Any peculiarities?" "It is smooth, but I won't say we can't run it better. We got rid of handling damage in the conveyors. The print quality suffers sometimes due to worn dies or a bad setup on the ink-stamp. The metal finish is pretty good, but the plastic trim sometimes leaves rough edges, and we have not been able to get a handle on that. I have wondered if it might be in the material, but I haven't been able to figure it out. Our vendors say nothing has changed, but then that's what I would expect them to say. Overall, things are running well, and we usually catch all the bad product at inspection." "Fred, thank you very much for the tour. It has been very informative. If you don't mind, I would like to get together with you again after I have talked to some other folks, and had a chance to think a little. We might be able to work on your material problem, too." You return to the conference room to change tapes, and make some notes on the tour. You realize that you don't yet know enough to begin a thorough analysis, but there are hints. After a short break, you walk to John Loomer's office. 2.4 John Loomer, QC Manager John Loomer has a degree in business, and has taken a few courses in statistics. He is a member of the American Society for Quality Control, and has attended a few ASQC workshops. He is a young man, and only has a few years of experience. Based on the Honcho interview, you assume that Loomer has primary responsibility for quality and is limited only by his knowledge of quality methodologies and processes. Major changes, however, will probably have to come from Honcho or Magnate. One of your objectives will be to enlist Loomer as an ally in your project, since he could easily block recommended changes. You begin by trying to determine his state of knowledge and experience. "Mr. Loomer, I appreciate your seeing me. I assume that Mr. Honcho has told you about my project. I want to assure you that I am not here to undermine the quality program you have installed. There may be recommended changes, but I would like to work with you on those recommendations." "I will admit I was a little concerned when I heard you were starting a project with quality as its focus. On the other hand, I know there is more to be done here. Why don't I bring you up to date on quality developments here at Etcetera?" "I would like to hear it." "Well, I was hired three years ago as QC Manager. That was my interest in college, and in my first job I was able to expand it and attend some seminars that were very useful. Irv and Walter wanted to institute a formal quality program, and hired me to do it. There was very little formal QC work at that time. Since then, I have concentrated on two areas: inspection, and customer complaints. I initiated a final inspection function, and hired and trained some inspectors. Until then, we had no idea of what our quality was. We found some problems right away on metal tags, that we traced to conveyor damage. Since then, things are going well for the most part." "Mr. Honcho told me you screen 100% of your products." "Yes, and that was a help, too. We found some assembly problems and a couple of others that operator training took care of. I make a point that the operators know that QC is there to improve the process, not get on somebody's case." "How is your customer feedback?" "Improving. The final inspection eliminated some complaints, but some others were due to shipping problems. Putting in a formal review of complaints helped us find that and fix it." "How does your formal review work?" "The receiving department sends all returns to me, and marketing sends me copies of complaint letters. We have a review committee of me, Edith Scriptus, and Fred Doit. We meet monthly and review returns and complaints, and then one of us takes action, depending on the problem." "Is Mr. Honcho involved in the review?" "Not formally, but I report to him from time to time on quality status and actions. He prefers to leave it to me and Fred, unless the problem involves other departments." "What is your overall assessment of quality here?" "It is improved, but there is more room for improvement. We have some potential material problems with edges that have been a nuisance. We still get too many complaints about print quality, too. Based on things I have read lately, I wonder if we might be getting as much as we are going to get from inspection. I have mentioned doing some process studies, but Fred and Walter say things are going pretty well, and they don't like to take productive time for experiments. Still, we are the best in the business, and we mean to stay that way." "Well, I need to think about what I have leamed so far. I like your idea about running some experiments; maybe we can talk them into it. Thanks for your help." 2.5 Edith Scriptus, Lead Engraver Edith Scriptus has been with the company for several years. She has worked in all of the production sections, and is expert in most of them. While she has no line management responsibility outside the custom engraving section, she is considered a valuable resource by Doit and Loomer. Her combination of experience and process knowledge is probably the best in the company. Her interview takes place in the engraving work area. It begins differently from the others when, in place of a greeting, she says, "So you're going to fix up the quality in this place. I wish somebody would!" "Is there a problem with quality here?" "Don't kid me. It would be nice to see some things fixed that have needed it for a long time." "You make it sound like there are chronic problems." "There are. We have gotten by for a long time by patching things, but I don't think we know enough to patch any more. If you can get Irv's attention and make Honcho take some action, that would be a good start. I'm no quality expert, but I can tell when a system isn't running as well as it should. I can also tell when people run in circles without making any progress, especially if I am one of them. We do too much of that." "What do you think of your quality systems?" "We do the best we can, but we don't do enough. John has done a lot of good, but he hasn't been around long enough to get to the deep problems. His inspection and training has helped; he found some problems and got them fixed. I'm afraid he is out of quick fixes, though. We're on top of our business right now, but if somebody starts beating us on quality and price, we could be in trouble." "I've been told your quality is the best in your business." "It is, but look at what it costs! It's better than before John came, as far as customers are concerned, but we work harder to get it. We used to run at about 80% of capacity. After inspection started, we still ship the same numbers, but now we run at 95% of capacity. We can't grow because we spend more time at inspection and rework. Honcho hasn't figured that out yet." "It sounds like you and Mr. Honcho don't agree on some things." "I like Honcho, don't get me wrong. It's just that he is in love with his equipment. It did a good job for a long time, but things have changed. We have new products, new materials. That ink-stamper, for example. That new process took a lot of load off my section, but it makes more rejects, and nobody knows why. Are you going to work on that?" "I might. My first step, though, is to do a study of the whole system and find out where all the problems are. I would appreciate your help." "I'll be glad to help. I've worked here for a long time, and I plan to retire here. I might as well make life easier on myself while I do it." "Ms. Scriptus, you have been very frank with me, and I appreciate it. I'm going to think about what you have said, and I will probably need some information on your processes later. I hope we can work on some of those deeper problems." "I'll be here." 2.6 Jim Bob Twister, Machine Operator Jim Bob Twister supervises operation of the presses and molding machines. He has been trained as a machinist, and has worked with Honcho in design and fabrication of some of the custom machinery. It was his work on the conveyors that reduced handling problems shortly after inspection began. His interview takes place in his shop near the metal presses. "Mr. Twister, thanks for setting aside some time for me. I suppose Mr. Honcho has told you about my quality study project." "Yes, he told me to give you some help. What exactly are you going to do?" "I don't know yet. Right now I just want to learn more about how things work and where people think the problems are. My objective is to work with all of you to find some ways to improve your quality. What is the biggest problem in your area?" "Well, the presses are working pretty well. Molding is my biggest headache. We have these edge problems, and we can't get rid of them. It's not a major problem, but it makes some rework. I told Fred I think our plastic supplier is throwing in some recycled stuff now and then." "How does that cause problems?" "I'm not sure how. But I know we have looked at practically every machine adjustment we can think of, and no matter what we do we get edge problems. And it's not consistent. It seems to me that it must be the material." "How about on the metal side? Do you have much die wear?" "We have some, but we have a handle on it. I have a schedule for die replacement, and as long as we stick to it, our quality is OK. I'm more concerned about the plastics." "Do you have time for some test runs?" "Sure. Just clear it with Fred, and let me know what you need." "Do you use SPC on your presses?" "No, not yet. I probably will, though, as soon as John gets around to it. I've been trained in SPC, and John wants to start a program. It might help." "How about the rest of your section? Have they been trained?" "No, just me. I don't think that will be a problem, though. They are pretty sharp fellows; they can pick it up." "Well, thanks for your time. I will be around for a few days, and I will probably be back for some more helpStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts