Question: QUESTION A) How was the performance management system in place in the case study representative of Traditional Public Administration (TPA) (give one characteristic/example and explain

QUESTION

A) How was the performance management system in place in the case study representative of Traditional Public Administration (TPA) (give one characteristic/example and explain how this is so (3 points) and

B) how are the recent efforts mentioned in the paper to change these practices related to New public management (NPM) (explain what the main change is and how this is representative of NPM vs TPA ( 3 points)?

PLEASE, label your answers and explain propely and relate your answer to the case study above.

give answer in 10 minutes.

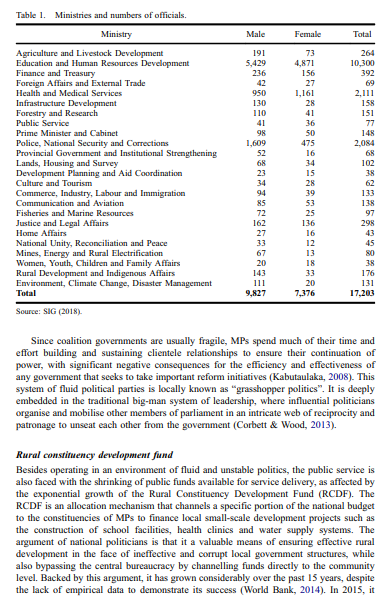

RESEARCH ARTICLE The Solomon Islands public service: organisations, challenges and reform Jude Devesi* Ministry of Public Service, Solomon Islands Government, P. O. Bax G29. Honiara, Salomon Islands (Received 4 September 2018; accepted 24 October 2018) This articles addresses various arrangements and dynamics of immediate significance to the structure and operation of the public service in the Solomon Islands. It describes responsibilities of core ministries and associated entities, along with a consideration of significant challenges and associated reform initiatives which seek to transform the way the public service is organised and works. The experience to-date indicates the extent to which the sustainability of reform depends on a complex array of factors, including a careful negotiation of both formal and informal governance practices within and beyond government. Keywords: public service, ministries, public service reform; performance manage- ment, strategic human resources governance; Solomon Islands Introduction The Solomon Islands is located in the southeast Pacific, between Vanuatu to the cast and Papua New Guinea to the west. The country comprises some 900 Islands, with a land mass of approximately 11,000 sqkms. The people are predominantly Melanesian (about 95%), with smaller Polynesian, Micronesian, Chinese and European communities. In the 2009 national census, the popula- tion was estimated at 515,870, of which approximately 80% live in rural areas (SIG, 2011). There are 83 distinct indigenous languages spoken, with Solomons Pidgin serving as the lingua franca. Besides language, differences in culture, beliefs, practices, and the structure of socio-economic and political life characterise the diversity of the people and the country. A complex web of kinship, lineage, social obligations, land tenure and entitlements underlies society and social identity. Of primary importance is the "wantok system", under which loyalty is ascribed to ethnic or familial groups, rather than to an island, province or the nation. Traditionally, the wantok system has been the social security of society and the communities still depend on this system in the linking of people across urban-rural, cash-subsistence, and public-private divides (McLeod & Herrington, 2016). While the population growth rate in the Solomon Islands declined from 2.8% in 1999 to 2.3% in 2009, it is still considered to be high, with estimates that the population will have reached 800,000 by 2024 (Katafono, 2017, p. 24). The country has a youthful population, with around 40% under the age of 15 years. Accordingly, one of the more pressing issues to be addressed concerns the needs of youth as they negotiate the challenges of a changing society. Failure to address these needs threatens to lead to increased social disorder and unrest. Progress on key social development indicators remain relatively low, with the country being ranked 156 on the human development index (UNDP, 2016). Between 1990 and 2015, the gross national income increased by only 14.8, with huge disparities existing between an urban minority population and the majority rural-based population. Development has focused on urban areas to the detriment of the wider rural community, as is reflected in differences in key indicators between rural and urban areas (UNDP, 2016). The economy is dependent on a small number of primary export products such as timber and fish, all of which are influenced by global market prices and climatic variations. The economy continues to improve from the shocks of recent years, but challenges loom such as increasing fuel prices. Real gross domestic product growth for 2019 is projected to be around 3.4% (SIG, 2018). That growth primarily reflects continued growth in such major sectors as agriculture, construction, manufacturing and the service sector, mainly retail and trade. The logging sector has been one of the key contributors to overall growth over the past years, although the volume of production is expected to slow down over the medium term once the government's sustainable devel- opment policy is implemented. The challenge for the government is to seek alternative sources of broad-based growth to offset the projected loss in logging revenues and to sustain the economy of the country over the medium term (SIG, 2018). Land is a key foundation of the society, and, as urbanisation has increased and more people have sought to join the cash economy, traditional and cultural norms have been undermined. Besides the serious implications for the environment and food security, the additional pressure of the need to generate income has led to serious conflict over land tenure. Rampant logging has seriously compromised customary resource management and land tenure, which is based on people's kinship relations and collective authority. Extractive resource activities have all but sidelined the role of women in traditional resource management and decision-making. In 1998, a major social crisis led to armed conflict between rival militant groups, the Isatabu Freedom Movement (IFM) of Guadalcanal and the Malaita Eagle Force (MEF). The resulting period of crisis between 1998 and 2000 led to more than 200 deaths, and the displacement of up to 35,000 people. In June 2000, MEF militants and elements of the police force broke open the police ammouries and took over the capital Honiara, deposing the government of prime minister Bart Ulufa'alu. In October 2000, the Townsville Peace Agreement (TPA) was concluded, providing for a general amnesty, weapons disarmament, and a restructuring of the Police Force. A National Peace Council was created to oversee the implementation of the TPA. Suggestions that the conflict was merely a clash between ethnic rivals ignored the broader context of cconomic change affected by globalisation, corruption, and the failure of a development model based on exploitation of natural resources such as timber and fisheries. The political and social conflicts involved arose from the interaction of local struggles for power and resources particularly land, paid employment, and services and global cconomic trends in trade and aid which disadvantage small island developing states. In response to a request from the government, an international police and military force was deployed to the country in July 2003, as the first stage of the Regional Assistance Mission to the Solomon Islands (RAMSI, 2018). RAMSI is a long-term cooperative intervention intended to address the crisis of development and governance that erupted in 1998. While it had early successes in relation to the restoration of law and order, its stated priority areas - support for the rule of law, budget stabilisation, and economic and public sector reform - have not fully addressed the root causes of the social tension. The success and sustainability of reform initiatives are highly question- able, as key challenges remain especially across the public service. Organisational arrangements The Constitution (1978) establishes the office of the prime minister, as well as that of other ministers, all of whom constitute the cabinet as a body to advise the head of state on the governance of the country. As with most parliamentary-executive arrangements, the cabinet is collectively responsible to parliament for all of the things done by or under the authority of any minister Core ministries and commissions Responsibility for the governance and management of the public service is jointly shared by the Ministry of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, the Public Service Commission (PSC), and the Ministry of Public Service. Other ministries such as the Ministry of Finance and Treasury and the Ministry of Development Planning and Aid Coordination also play roles regarding fiscal allocation and control, as well as policy development and coordination across all ministries. Prior to the separation of the Ministry of Public Service from the Ministry of the Prime Minister and Cabinet in 2007, the prime minister was responsible for the govem ment's HRM functions under a dedicated division called the public services division. At present, the Ministry of the Prime Minister and Cabinet is still responsible for the HRM functions in relation to permanent secretaries, constitutional post holders and political advisors, usually in consultation with the PSC. The public service and PSC are provided for in the Constitution (1978). The PSC consists of a chair and four other members, who are appointed by the head of state acting on the advice of the prime minister for a term of three to six years. The main functions of the PSC are to make appointments to public offices (including the confirmation of appointments after probation), and to exercise disciplinary control over all public offi- cials, including removing them from office. Besides the PSC, there are three other commissions: the Teaching Service Commission, the Judicial and Legal Services Commission, and the Police and Correctional Services Commission. The chair of the PSC is also the chair of the first two of these commissions, and is a member of the third. The PSC and other commissions are supported and serviced by a single secretariat located within the Ministry of Public Service. The Public Service Act (1988) grants the Minister for the Public Service responsi- bilities and powers concerning the reorganisation of the public service, in consultation with the PSC. The responsibilities and powers include the creation, amalgamation or abolition of new divisions within the public service, and the development, amendment or abolition of schemes of service for public officers. They also include the conduct of an inquiry or review of the administration of ministries, leading to possible changes in practices and procedures, as well as the review and approval of the postings of public officials within the headquarters of ministries and to the provinces. These responsibilities and powers are complemented by the Minister for the Public Service being authorised to make rules, regulations, orders, policies and guidelines conceming a range of matters. Included are the public service remuneration structure and position classification system, the expected conduct of public officials, the training and professional development of public officials, the management of the performance of public officials, and the proper organisation and efficient conduct of the business of the government; and the allocation, care and use of government property. Overall responsibility for the management of the country's finances rests with the Ministry of Finance and Treasury, which advises the government on taxation policies, collects revenue, and prepares the recurrent budget. The legislative framework guiding its operations include the Public Financial Management Act (2013) and the financial instructions which provide for the processes and procedures of prudent financial manage- ment. It also pays for all goods and services procured by other ministries and agencies, and ensures compliance with the regulation of fiscal spending. Annually, it sets the government payroll budget based on a manpower establishment prepared by the Ministry for Public Service, with a requirement that the establishment be tabled in parliament together with the budget documents for appropriation. It is consulted before a decision is made to award financial benefits for public officials in terms of remuneration policies and schemes of services for different occupational groups in the public service. Another core ministry is the Ministry of Development Planning and Aid Coordination, which has responsibility for the formulation and monitoring of the coun- try's development budget. It also coordinates all donor-funded activities and projects, ensuring alignment with the National Development Strategy 2016-2035 (2016) and policy priorities of the government. Other ministries Including the ministries addressed above, there are 24 ministries in the public service. They are listed in Table 1, along with their numbers of officials. Significant challenges The public service has faced, and continues to face, several significant challenges inherent in its environment, as well as internally. The challenges remain, despite recent reform initiatives having sought, among other objectives, to reduce their impact and, thereby, enable the public service to function more efficiently and effectively than it has to-date Unstable operating environment A long-standing feature of the country's political landscape is the weak political party system, which has been referred to as a system of "unbounded politics" (Steeves, 1996). Political parties are not sufficiently strong in fostering and maintaining the loyalty of elected members to ensure that the party controls their legislative behaviour. It is a regular occurrence, for example, for a member of the opposition group in parliament to resign from their post to take up a ministerial appointment in a government that they may have spent many years opposing. This illustrates the porous nature of the boundary between the opposition and government, and the fact that local politicians generally have weak loyalty to parties (Kabutaulaka, 2008). Because political allegiances change reg- ularly and political instability is endemic, it is difficult for ministries to implement medium and long-term policies and programmes, including much-needed public service reform. It has become common practice for a newly elected prime minister to discard previous programmes of change and reform in favour of new programmes, so that they can take credit for their outcomes. Table 1. Ministries and numbers of officials. Male Female Total 5,429 42 Ministry Agriculture and Livestock Development Education and Human Resources Development Finance and Treasury Foreign Affairs and External Trade Health and Medical Services Infrastructure Development Forestry and Research Public Service Prime Minister and Cabinet Police, National Security and Corrections Provincial Government and Institutional Strengthening Lands, Housing and Survey Development Planning and Aid Coordination Culture and Tourism Commerce, Industry, Labour and Immigration Communication and Aviation Fisheries and Marine Resources Justice and Legal Affairs Home Affairs National Unity, Reconciliation and Peace Mines, Energy and Rural Electrification Women, Youth, Children and Family Affairs Rural Development and Indigenous Affairs Environment, Climate Change, Disaster Management Total 989813303972CARCADE 73 4,871 156 27 1,161 28 41 36 50 475 16 34 15 28 39 53 25 136 16 12 13 18 33 20 7,376 264 10,300 392 69 2.111 15 151 77 148 2.084 68 102 38 133 138 97 298 43 45 80 38 176 131 17,203 9,827 Source: SIG (2018) Since coalition governments are usually fragile, MPs spend much of their time and effort building and sustaining clientele relationships to ensure their continuation of power, with significant negative consequences for the efficiency and effectiveness of any government that seeks to take important reform initiatives (Kabutaulaka, 2008). This system of fluid political parties is locally known as "grasshopper politics". It is deeply embedded in the traditional big-man system of leadership, where influential politicians organise and mobilise other members of parliament in an intricate web of reciprocity and patronage to unseat each other from the government (Corbett & Wood, 2013). Rural constituency development fund Besides operating in an environment of fluid and unstable politics, the public service is also faced with the shrinking of public funds available for service delivery, as affected by the exponential growth of the Rural Constituency Development Fund (RCDF). The RCDF is an allocation mechanism that channels a specific portion of the national budget to the constituencies of MPs to finance local small-scale development projects such as the construction of school facilities, health clinics and water supply systems. The argument of national politicians is that it a valuable means of ensuring effective rural development in the face of ineffective and corrupt local government structures, while also bypassing the central bureaucracy by channelling funds directly to the community level. Backed by this argument, it has grown considerably over the past 15 years, despite the lack of empirical data to demonstrate its success (World Bank, 2014). In 2015, it reached a high of SBD 426 million (US$50million), which represented 12% of total budgeted expenditure for the year (Batley, 2015). In reality, the RCDF is highly politicised and used to reward supporters of politicians with development projects as a form of consolidating voter support for national elections (Fraenkel, 2008; Wood, 2014). There is a notable absence of transparency in the way allocation decisions are made, as funding applications received from communities are deliberated on by a screening committee which is handpicked by the MP concerned. Also, as it sole custodian, the MP gives final approval before funds are disbursed. More often than not, it has also been used as a fund to meet the personal needs of constituents such as wedding and funeral expenses, reinforced by community expectations that MPs will take responsibility for people's welfare in their role as big-men. Overall, it con- tributes to the weakening of national and sub-national structures because it completely bypasses them and sets up a parallel system of service delivery in rural communities (World Bank, 2014). Performance management A key factor affecting performance in the public service is its organisational culture, which is characterised by an out-dated notion of permanent employment. As with public services in many other countries, it is one of the most secure employers in the country, which creates a tendency for a majority of public officials to accept the status quo with very little incentive to adapt to change. Until recently, the performance management system for individual performance was based on an annual confidential report, whereby a supervisor completed a performance report without the provision of any form of feedback or information to the employee. Under this system, annual salary increments were automatically given regardless of performance. Over the last three years, an attempt has been made to orient the mindset of public officials towards performance rewards and to link individual performance to organisa- tional goals and objectives. While there have been some modest achievements concer- ing these matters, progress remains limited. Most performance reports received by the Ministry of Public Service for the awarding of increments still give a majority of officials extremely high ratings, without supervisor-staff interviews having been conducted. This is partly attributable to societal values and norms of non-confrontation, as well as to the culture of secretive and closed communication that permeates the public service. There is also a key task of assessing the performance of ministries and related agencies in an operating environment where reporting systems are weak or close to non- existent. The Ministry of Development Planning and Aid Coordination plays a basic monitoring and evaluation role in terms of the implementation of development budget, but the role is limited to macro-level evaluations and based on proxy indicators of budget expenditure. This limitation is compounded by the corporate planning cycle for the entire government not being synchronised into a single planning framework in which ministry activities are aligned with one another and with the government's goals and priorities. Misconduct and corruption The PSC, which is responsible for the discipline of public officials, has faced capacity constraints in its key mandated area to investigate cases of misconduct, and, as a result, has a delegated this responsibility either to the permanent secretary of the public service under the auspices of the professional standards unit in the Ministry of Public Service, or to permanent secretaries for each of the other ministries. These officials also struggle to carry out this function, given very limited resources and human capacity. At present, there are only three staff in the professional standards unit who have responsibility for investigating cases of misconduct for senior level officials. Misconduct cases of lower level officials are seldom investigated because of capacity constraints and the reluctance of permanent secretaries to handle cases of misconduct in office. Also, dealing effectively with mis- conduct relies heavily on strong reporting mechanisms, and the absence of such a mechanism in the public service has meant that efforts only address the tip of the iceberg. The relatively low level of remuneration and financial benefits awarded to public officials has also contributed to the problem of mismanagement and corruption across the public service, with many of the misconduct cases involving fraud and embezzlement of public funds. Significantly, this high level of official corruption cannot be attributed to a lack of knowledge of relevant govemment procedures and policies, as a survey conducted for the PSC (2016) found that 84% of public officials included in the survey had a clear understanding of the behaviour expected of them by the public service code of conduct, and 93% were aware that there are consequences if the code of conduct is not followed. The same survey (PSC, 2016) found that 50% of citizen respondents had little or no confidence in the government's ability to handle economic challenges. This was attrib- uted largely to favouritism inherent in the wantok system and to the acceptance of bribes or extra payments for services provided. Coordination and a whole-of-government approach Despite the clearly defined roles of core ministries in the public service, horizontal coordination to ensure that all ministries align their work with the policy goals and priorities of the government remains very weak. The establishment of cabinet sub- committees with secretarial support from political advisors has sought partly to address this problem over the last few years, but with frequent changes of government, their institutional memories have been short-lived. The present government has established a central ministries coordinating committee, which is chaired by the prime minister and comprises the Ministers of Finance, Public Service, and Planning. The creation of this committee is seemingly a step in the right direction, but the effect of its activities are yet to be felt. In order for central policy coordination work to be successful, there is also a need to strengthen the interface between ministers and their permanent secretaries. Open and frequent communication between them is a key requirement in the implementation of the policy commitments of the govemment. Recent cases suggest that such communication has not occurred, with ministers often neglecting their ministerial duties in favour of constituency matters. This reinforces the system of patronage polities and contributes to a lack of political will or interest in national affairs, as ministers are heavily focused on retaining their parliamen- tary seats. Reform initiatives In October 2017, the cabinet approved the Public Service Transformation Strategy 2017-2021 (2017) for implementation across the public service. This strategy was formulated by a team of public officials with no technical assistance from outside the country. It seeks to shift away from the conventional approach of human resources management to a more transformative leadership approach. In doing so, it addresses the need for the following strategic objectives to be pursued. Strategie human resources governance A major initiative underway involves the review and recasting of the outdated Public Service Act (1988), with the noble intention of modernising the public service. The rules and regulations goveming, for example, the conduct of public officials have become irrelevant and disenfranchised from the reality of today's public service. In response, the Ministry of Public Service has recently considered the public service systems in Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, and Vanuatu in terms of the various organisational power-sharing arrangements for the management of the public service in these countries, and how the arrangements have been crafted to suit their specific country contexts. A result is that a Public Service Bill has been drafted for tabling in parliament after the general elections in early 2019. Organisational development A significant aim of organisational development is to create a sound corporate culture arising from a review and restructuring of the public service to ensure the effective and efficient delivery of services throughout the country. The Ministry of Public Service is embarking on a first-ever whole-of-government functional review exercise, beginning with the building of staff capacity to undertake the review, as opposed to hiring consultants to do it. As part of the process, several ministries have been identified for review, with relevant training having been provided for their staff. A functional review guideline mapping out the different processes involved has been developed as a way to sustain the work, particularly in the face of staff tumover and movements. E-governance Action is being taken to transform the public service from physical to digital business processes, using the present human resource management information system as a starting point to strengthen and reinforce arrangements for workforce planning and management. The major achievement to-date has been the electronic roll-out of a system across the public service. The usage of it has increased to almost 60% of all employees, despite the slow connectivity and high costs of internet access across the country. In this regard, the development of the high speed fibre optic cable into the country has high promises for transforming the e-governance basis of the public service. Remuneration system The underlying aim of transforming the remuneration system is to ensure a fair and affordable compensation framework which links financial and non-financial rewards to individual and organisational performance. The first major step involves the conducting of a review of the existing public service reward system, leading to the development of options for the government which are fair, affordable and aimed at increasing staff morale and retention. With the support of an extemal development partner, relevant material has been produced to guide this area of reform. Immediate needs are to simplify and harmonise the present complex system of allowances, and to formulate a robust job evaluation methodology that ascribes values to jobs in the public service. Learning and talent development Initiatives conceming learning and development appreciate the vital need for continuous improvement in the capacity, competency and skills of public officials at all levels, along with the encouragement and facilitation of continuous knowledge seeking and skills development. The main driver is the Institute for Public Administration and Management, which is the training agency of the government. Gender in governance The creation of an enabling environment for equality in the participation of women and men in essential in the development of the public service. The first stage of this work involves putting in place a gender and social inclusion policy, coupled with capacity building work of gender focal persons in each ministry and related agencies. Work is also to be undertaken to promote women into leadership positions across the public service through the provision of mentoring programmes by the PSC and Ministry of Public Service. Research and innovation The building of learning organisations requires comprehensive research and innovation. There is a need to encourage the generation and sharing of innovative ideas that will lead the public service into the future. A research and innovation team has been established in the Ministry of Public Service to act as the hub for knowledge management and dissemination across the public service. Concluding comments Recent locally-driven reform initiatives constitute a major shift from past practice involving reforms largely having been driven externally. Previous governments have suffered from political inertia and a lack of political will to drive reform from the top, leading to very limited change. The present government has the political support and will to proceed confidently in the implementation of the latest reform agenda. But to be successful in this regard, it also needs to facilitate considerable political reform with the aim of achieving a wide array of desired outcomes for the societyStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

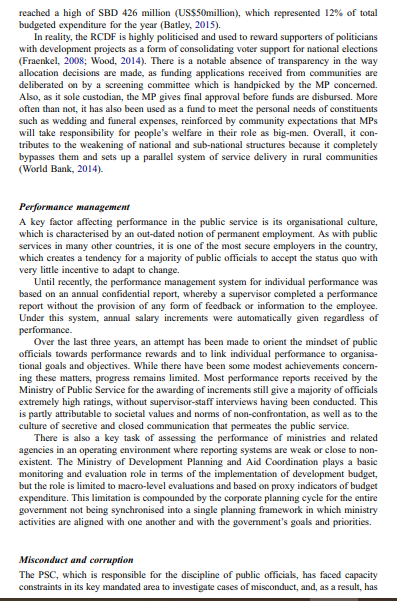

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts