Question: Question: What is a social construction? As social constructions, how are race and gender the same and how do they differ? What does it mean

Question:

What is a social construction? As social constructions, how are race and gender the same and how do they differ? What does it mean to say, Gender becomes a social construction like race when it is treated as an unchanging, fixed difference and then used to deny opportunity and equality to women? Consider the changing social constructions of race over time suggested by the Census Bureau categories. What do you make of them? Which categories make sense to you and why? How do those categories reflect particular meanings or ways of thinking at the time?

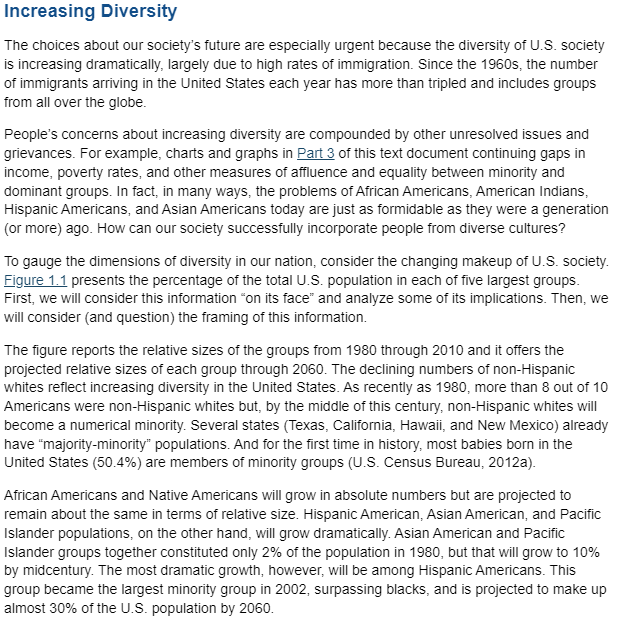

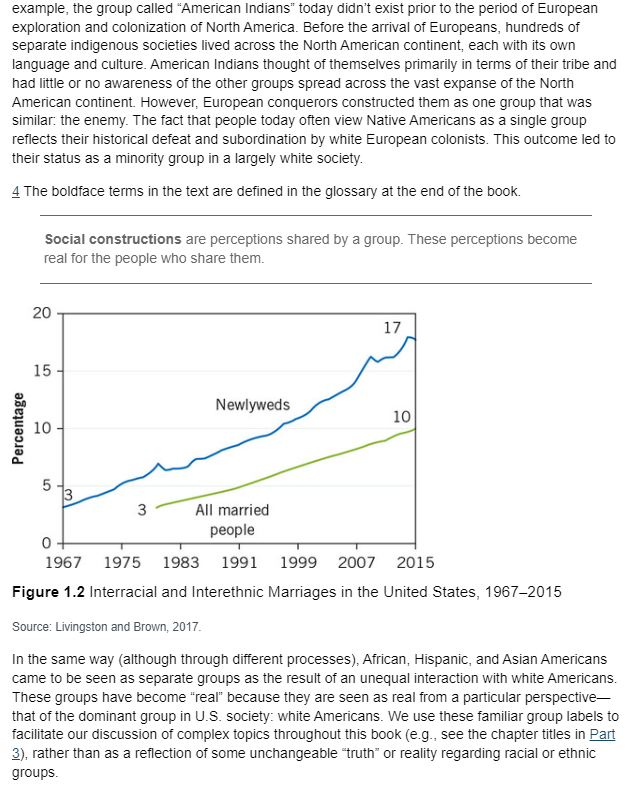

Increasing Diversity The choices about our society's future are especially urgent because the diversity of U.S. society is increasing dramatically, largely due to high rates of immigration. Since the 1960 s, the number of immigrants arriving in the United States each year has more than tripled and includes groups from all over the globe. People's concerns about increasing diversity are compounded by other unresolved issues and grievances. For example, charts and graphs in Part 3 of this text document continuing gaps in income, poverty rates, and other measures of affluence and equality between minority and dominant groups. In fact, in many ways, the problems of African Americans, American Indians, Hispanic Americans, and Asian Americans today are just as formidable as they were a generation (or more) ago. How can our society successfully incorporate people from diverse cultures? To gauge the dimensions of diversity in our nation, consider the changing makeup of U.S. society. Figure 1.1 presents the percentage of the total U.S. population in each of five largest groups. First, we will consider this information "on its face" and analyze some of its implications. Then, we will consider (and question) the framing of this information. The figure reports the relative sizes of the groups from 1980 through 2010 and it offers the projected relative sizes of each group through 2060 . The declining numbers of non-Hispanic whites reflect increasing diversity in the United States. As recently as 1980, more than 8 out of 10 Americans were non-Hispanic whites but, by the middle of this century, non-Hispanic whites will become a numerical minority. Several states (Texas, California, Hawaii, and New Mexico) already have "majority-minority" populations. And for the first time in history, most babies born in the United States (50.4\%) are members of minority groups (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012a). African Americans and Native Americans will grow in absolute numbers but are projected to remain about the same in terms of relative size. Hispanic American, Asian American, and Pacific Islander populations, on the other hand, will grow dramatically. Asian American and Pacific Islander groups together constituted only 2% of the population in 1980 , but that will grow to 10% by midcentury. The most dramatic growth, however, will be among Hispanic Americans. This group became the largest minority group in 2002, surpassing blacks, and is projected to make up almost 30% of the U.S. population by 2060. Figure 1.1 The U.S. Population by Race and Ethnicity, 19802060 (Projected) Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census (2015a). Note: "Hispanics" may be of any race. Projections about the future are just educated guesses based on documented trends; but, they suggest profound change. Our society will grow more diverse racially and culturally, becoming less white and less European, and more like the world as a whole. Some people see these changes as threats to "traditional" white, middle-class American values and lifestyles. Other people view them as an opportunity for other equally legitimate value systems and lifestyles to emerge. Which of these viewpoints are most in line with your own and why? What's in a Name? Let's take a moment to reflect on the categories used in Figure 1.1. The group names we used are arbitrary, and none of these groups have clear or definite boundaries. We use these terms because they are familiar and consistent with the labels used in census reports, much of the sociological research literature, and other sources of information. So, while such group names are convenient, this does not mean that they are "real" in any absolute sense or equally useful in all circumstances. In fact, these group names have some serious shortcomings. For example, group labels reflect social conventions whose meanings change from time to time and place to place. To underscore the social construction of racial and ethnic groups, we use group names interchangeably (e.g., blacks and African Americans; Hispanic Americans and Latinos). Further issues remain. First, the race/ethnic labels suggest groups are largely homogeneous. However, while it's true that people within one group may share some general, superficial physical or cultural traits (e.g., language spoken), they also vary by social class, religion, gender, sexual orientation, and in many other ways. People within the Asian American and Pacific Islander group, for example, represent scores of different national backgrounds (Japanese, Pakistanis, Samoans, Vietnamese, and so forth), and the category "American Indian or Alaska Native" includes people from hundreds of different tribal groups. If we consider people's other social statuses such as age and religious affiliation, that diversity becomes even more pronounced. Any two people within one of these groups (e.g., Hispanics) might be quite different from each other in some respects while being similar to people from "different" racial/ethnic groups (e.g., whites). Second, people do not necessarily use these labels when they think about their own identity. In this sense, the labels are not "real" or important for all the people in these racial/ethnic groups. For example, many whites in the United States (like William Buford, mentioned in the "Some American Stories" part of this chapter) think of themselves as "just American." A Hispanic American (like Hector Gonzalez or Juan Yancy) may think of themselves more in national terms, as Mexicans or Cubans or, even more specifically, they may identify with a particular region or village in their homeland. Gay or lesbian members within these groups may identify themselves more in terms of their sexual orientation than their race or ethnicity. Thus, the labels do not always reflect the ways people think about themselves, their families, or where they come from. The categories are statistical classifications created by researchers and census takers to help them organize information and clarify their analyses. They do not grow out of or always reflect the everyday realities of the people who happen to be in them. Third, even though the categories in Figure 1.1 are broad, several groups don't neatly fit into them. For example, where should we place Arab Americans and recent immigrants from Africa? These groups are relatively small (about 1 million people each), but there is no clear place for them in the current categories. Should Arab Americans be included as "Asian," as some argue? Should recent immigrants from Africa be placed in the same category as African Americans? Should there be a new group such as Middle Eastern or North African descent (MENA)? Of course, we don't need to have a category for every person, but we should recognize that classification schemes like the one used in Figure 1.1 (and in many other contexts) have boundaries that can be somewhat ambiguous. A related problem with this classification scheme will become increasingly apparent in the years to come: there is no category for the growing number of people who (like Juan Yancy) are members of more than one racial or ethnic group. The number of "mixed-group" Americans is relatively small today, about 3% of the total population (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2015 a). However, the number of people who chose more than one racial or ethnic category on the U.S. Census to describe themselves increased by 32% (from 2.4% to 2.9% of the total population) between 2000 and 2010 (Jones \& Bullock, 2012) and is likely to continue to increase rapidly because of the growing number of marriages across group lines. To illustrate, Figure 1.2 shows dramatic increases in the percentage of "new" marriages (couples that got married in the year prior to the survey date) and all marriages that unite members of different racial or ethnic groups (Livingston \& Brown, 2017). Obviously, the greater the number of mixed (racial or ethnic) marriages, the greater the number of "mixed" Americans. One study estimates that the percentage of Americans who identify with "two or more races" will more than double between 2014 (when it was 2.5\%) and 2060 (when it will be 6.2\%) (Colby \& Ortman, 2015 , p. 9). Finally, we should note that these categories and group names are social constructions, 4 created in particular historical circumstances and reflective of particular power relationships. For example, the group called "American Indians" today didn't exist prior to the period of European example, the group called "American Indians" today didn't exist prior to the period of European exploration and colonization of North America. Before the arrival of Europeans, hundreds of separate indigenous societies lived across the North American continent, each with its own language and culture. American Indians thought of themselves primarily in terms of their tribe and had little or no awareness of the other groups spread across the vast expanse of the North American continent. However, European conquerors constructed them as one group that was similar: the enemy. The fact that people today often view Native Americans as a single group reflects their historical defeat and subordination by white European colonists. This outcome led to their status as a minority group in a largely white society. 4 The boldface terms in the text are defined in the glossary at the end of the book. Social constructions are perceptions shared by a group. These perceptions become real for the people who share them. Figure 1.2 Interracial and Interethnic Marriages in the United States, 1967-2015 Source: Livingston and Brown, 2017. In the same way (although through different processes), African, Hispanic, and Asian Americans came to be seen as separate groups as the result of an unequal interaction with white Americans. These groups have become "real" because they are seen as real from a particular perspectivethat of the dominant group in U.S. society: white Americans. We use these familiar group labels to facilitate our discussion of complex topics throughout this book (e.g., see the chapter titles in Part 3 ), rather than as a reflection of some unchangeable "truth" or reality regarding racial or ethnic groupsStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

1 Expert Approved Answer

Step: 1 Unlock

Question Has Been Solved by an Expert!

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts

Step: 2 Unlock

Step: 3 Unlock