Question: Question: Year Up was started in the year 2000 when the internet were struggling with the millennial bug. Fast track to 2021 a lot of

Question:

Year Up was started in the year 2000 when the internet were struggling with the millennial bug. Fast track to 2021 a lot of changes have taken place. Year Up is now dealing with the effect of Covid19 and generation Z which are more tech savvy and prefers to be self-employed (gigsters). How best can Year Up deal with the current situations? Based on your experience, what new social innovations can Year Up introduces how and should it be done to move the company to the next level? (15 Marks)

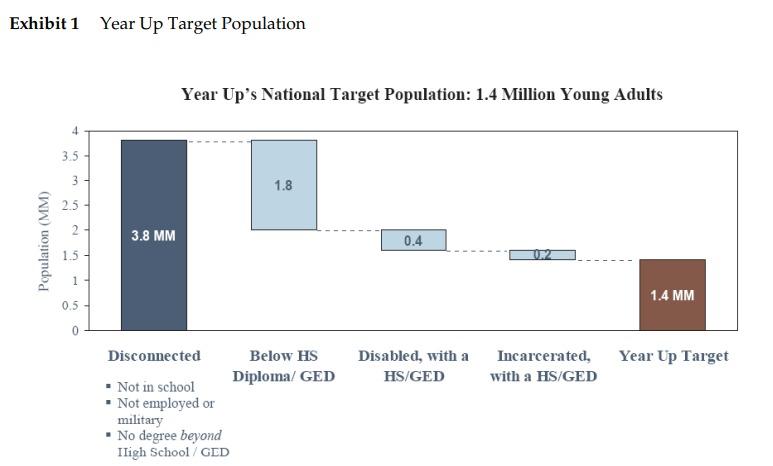

We are facing the challenges of scaling from a small to a midsize organization, managing sites across the country, and maintaining high quality in all of our programs. So far, we have done a few things right, but we are only on first base. There are 4.3 million disconnected young adults out there, so to anyone who says we have done well, I would point out that we have done nothing compared to the overall problem in our country. - Gerald Chertavian, Founder and CEO, Year Up It was a drizzly early spring morning in Boston in 2008 as Gerald Chertavian walked the halls of the new national headquarters of Year Up (YU). The fully renovated downtown Boston office represented another milestone achieved in the ambitious growth that YU, a job-skills training program for at-risk young adults, was undergoing. After its founding in 2000 and the opening of its first site in Boston in 2001, the organization had added three more sites in eastern cities, and it was poised to open in San Francisco in the fall and Atlanta over the coming winter. But YU's expansion was only beginning. The goal was to have a national footprint and be fully operational in eight urban centers by 2011. Rapid growth brought a number of pressing questions for Chertavian. While the recent capital campaign had been successful, would it be possible, without additional major fundraising, to achieve all of YU's ambitious objectives? Chertavian considered YU's leadership team second to none in the nonprofit sector, but would he be able to continue to find candidates with the unique skills that the organization needed? Would the close ties he had with his staff and the students erode as YU grew? Also, although the Boston board had been extremely effective, YU needed a national board, with members from across the country. How would he identify them and interest them in an organization that was currently only in four eastern cities? Each YU site needed a local board, and while one site had been successful in recruiting members, the other two had recruited a total of six people for this role. Perhaps the most gnawing worry of all was, would YU be able to sustain program quality as it grew to eight sites, to twenty-five sites? Even if it met all of its growth objectives, how much impact would the organization have on improving the lot of the 4.3 million young people he knew needed assistance? The list of unanswered questions went on, but it was time to spend an hour in class with his current group of excited and hopeful YU students. The Organization Gerald Chertavian graduated from Harvard Business School (HBS) with honors in 1992. He went on to co-found Conduit Communications, a London-based Internet strategy consulting firm. When he sold the company in 1999, he returned to the business plan for starting a nonprofit organization that he had written in 1989 as a part of his HBS application. While working on Wall Street before business school, Chertavian had volunteered as a Big Brother to a resident of a low-income public housing project. Chertavian saw that David, his Little Brother, along with many of the other young community residents, were stuck on the opposite side of what he called the "opportunity divide" they were talented and gifted yet lacked the support, education, and experience to become part of the economic mainstream in America. Research supported his disturbing observation. Students from low-income families left school at six times the rate of their peers from high-income families, and less than 10% of them ever earned a college degree. By 2015, according to the Department of Labor, eight out of ten jobs would require some form of training beyond high school. Even one year of post-secondary education increased lifetime earnings by an average of 5% to 15% per year. In 2004, the Annie E. Casey Foundation estimated that 3.8 million American young adults were neither employed nor enrolled in any post- secondary schooling (by 2006 the Foundation estimated that this population had grown to roughly 4.3 million). This represented nearly 15% of all 18 to 24-year-olds in the country. Of this population, 1.4 million had finished high school or completed a Graduate Equivalency Diploma (GED), and roughly 700,000 lived in the country's 30 largest urban centers (see Exhibit 1). This was YU's target populationlow-income, urban young adults, or what the policy community termed "disconnected youth." Chertavian outlined a plan for a school that would bridge the opportunity divide by training low- income urban young adults for careers in the economic mainstream. A job-training program for this population was not a new idea. However, Chertavian believed that his program would fill an unmet need for skilled technology workers. While other job-training programs had previously attempted to connect disengaged young adults with sustainable careers, they tended to be organizations with limited reach. Chertavian intended to build a scalable business model that had the potential to measurably impact the national problem. In January 2001 he opened Year Up in Boston. Its mission statement read: "Our mission is to close the opportunity divide by providing urban young adults with the skills, experience, and support that will empower them to reach their potential through professional careers and higher education." The new 501(c)(3) youth services and job-skills training organization welcomed its first class of 22 high school graduates, some of whom had limited college experience, but none of whom had prospects other than minimum-wage employment. The objective was to engage them in a year-long process that would transform them into highly qualified IT employees. Exhibit 1 Year Up Target Population Year Up's National Target Population: 1.4 Million Young Adults 4 3.5 3 1.8 2.5 2 Population (MM) 3.8 MM 0.4 1.5 1 - 1.4 MM 0.5 0 Disabled, with a HS/GED Incarcerated, with a HS/GED Year Up Target Disconnected Below HS Not in school Diploma/GED . Not employed or military - No degree beyond IIigh School / GEDStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts