Question: Read and study all the material and the Case Study: American Investment Management Services in Week 9 before beginning the final exam. Exhibits are found

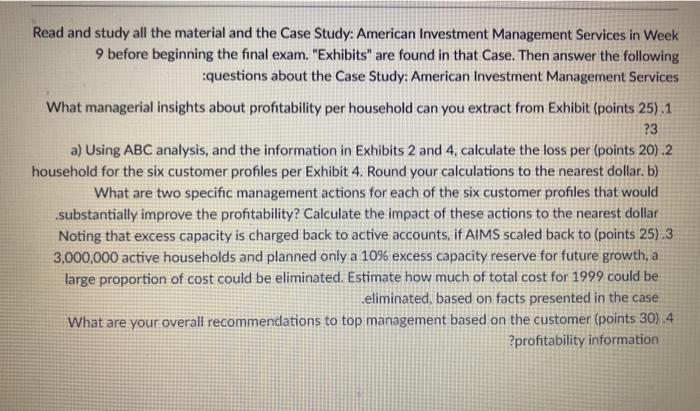

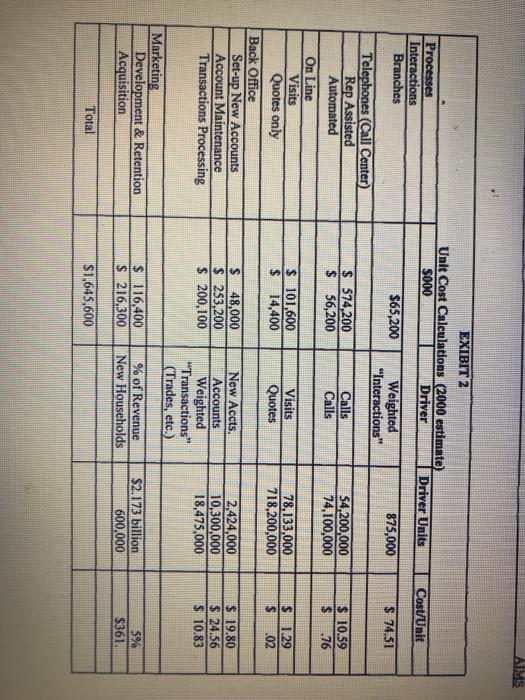

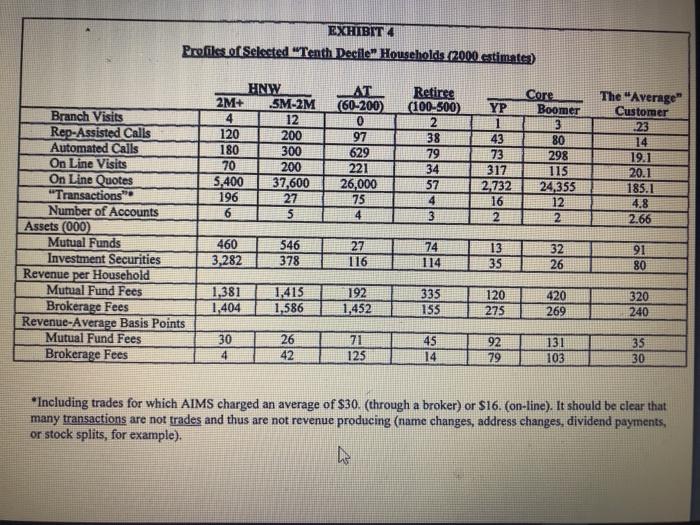

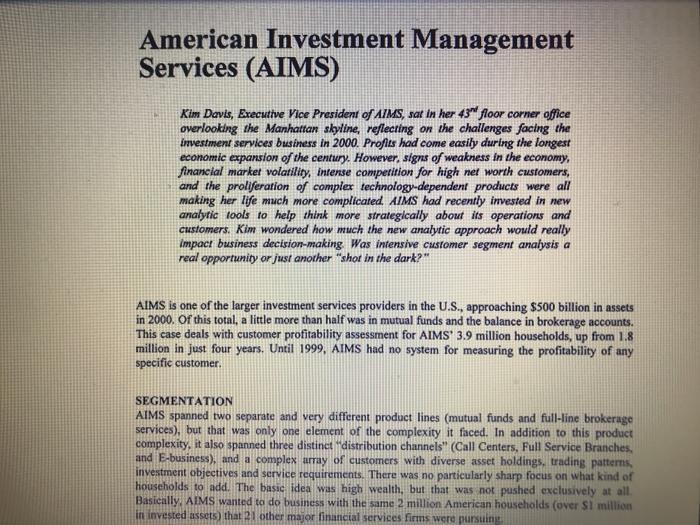

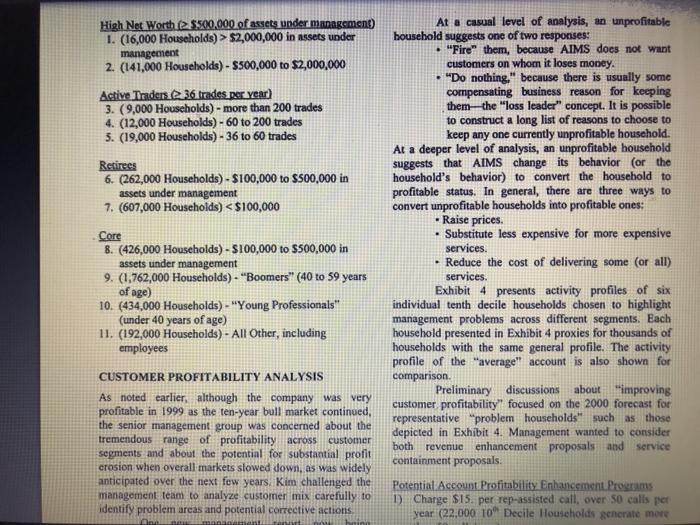

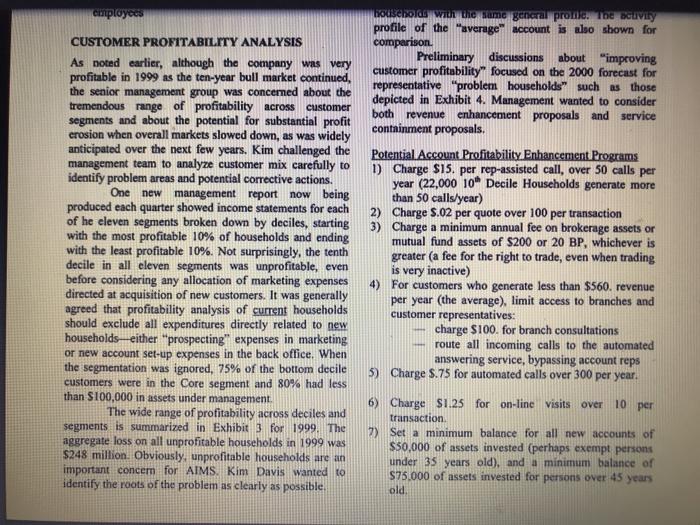

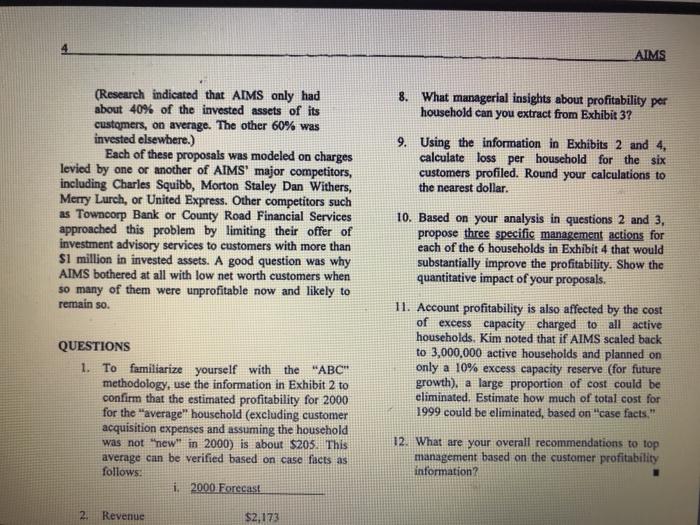

Read and study all the material and the Case Study: American Investment Management Services in Week 9 before beginning the final exam. "Exhibits" are found in that case. Then answer the following questions about the Case Study: American Investment Management Services What managerial insights about profitability per household can you extract from Exhibit (points 25).1 23 a) Using ABC analysis, and the information in Exhibits 2 and 4, calculate the loss per (points 20).2 household for the six customer profiles per Exhibit 4. Round your calculations to the nearest dollar. b) What are two specific management actions for each of the six customer profiles that would substantially improve the profitability? Calculate the impact of these actions to the nearest dollar Noting that excess capacity is charged back to active accounts, if AIMS scaled back to (points 25).3 3,000,000 active households and planned only a 10% excess capacity reserve for future growth, a large proportion of cost could be eliminated. Estimate how much of total cost for 1999 could be .eliminated based on facts presented in the case What are your overall recommendations to top management based on the customer (points 30).4 ?profitability information AIMS EXIBIT 2 Unit Cost Calculations (2000 estimate) $000 Driver Driver Units Cost/Unit Processes Interactions Branches $65,200 Weighted "Interactions" 875,000 $ 74.51 $ 574,200 $ 56,200 Calls Calls 54,200,000 74,100,000 $ 10.59 $ 76 Telephones (Call Center) Rep Assisted Automated On Line Visits Quotes only Back Office Set-up New Accounts Account Maintenance Transactions Processing $ 101,600 $ 14,400 Visits Quotes 78,133,000 718,200,000 wo S 1.29 .02 $ 48,000 $ 253,200 $ 200,100 New Accts. Accounts Weighted "Transactions" (Trades, etc.) 2.424,000 10,300,000 18,475,000 $ 19.80 $ 24.56 $ 10.83 Marketing Development & Retention Acquisition $ 116,400 S 216,300 % of Revenue New Households $2.173 billion 600.000 5% $361. Total $1,645,600 EXHIBIT 4 Profiles of Selected "Tenth Decile Households (2.000 estimates) HNW 2M+ .5M-2M 4 12 120 200 180 300 70 200 5,400 37,600 196 27 6 5 (60-200) 0 97 629 221 26,000 75 4 Retiree (100-500) 2 38 79 34 57 4 3 Core YP Boomer 1 3 43 80 73 298 317 115 2.732 24 355 16 12 2 2 The "Average" Customer 23 14 19.1 20.1 185.1 4.8 2.66 Branch Visits Rep-Assisted Calls Automated Calls On Line Visits On Line Quotes "Transactions" Number of Accounts Assets (000) Mutual Funds Investment Securities Revenue per Household Mutual Fund Fees Brokerage Fees Revenue-Average Basis Points Mutual Fund Fees Brokerage Fees 74 460 3,282 546 378 27 116 13 35 114 32 26 91 80 1,381 1,404 1.415 1,586 192 1.452 335 155 120 275 420 269 320 240 30 4 26 42 71 125 45 14 92 79 131 103 35 30 "Including trades for which AIMS charged an average of $30. (through a broker) or $16. (on-line). It should be clear that many transactions are not trades and thus are not revenue producing (name changes, address changes, dividend payments, or stock splits, for example). American Investment Management Services (AIMS) Kim Davis, Executive Vice President of AIMS, sat in her 43" floor corner office overlooking the Manhattan skyline, reflecting on the challenges facing the investment services business in 2000. Profits had come easily during the longest economic expansion of the century. However, signs of weakness in the economy, financial market volatility, intense competition for high net worth customers, and the proliferation of complex technology-dependent products were all making her life much more complicated. AIMS had recently invested in new analytic tools to help think more strategically about its operations and customers. Kim wondered how much the new analytic approach would really impact business decision-making. Was intensive customer segment analysis a real opportunity or just another "shot in the dark?" AIMS is one of the larger investment services providers in the U.S., approaching $500 billion in assets in 2000. Of this total, a little more than half was in mutual funds and the balance in brokerage accounts. This case deals with customer profitability assessment for AIMS' 3.9 million households, up from 1.8 million in just four years. Until 1999. AIMS had no system for measuring the profitability of any specific customer. SEGMENTATION AIMS spanned two separate and very different product lines (mutual funds and full-line brokerage services), but that was only one element of the complexity it faced. In addition to this product complexity, it also spanned three distinct distribution channels" (Call Centers, Full Service Branches, and E-business), and a complex array of customers with diverse asset holdings, trading patterns investment objectives and service requirements. There was no particularly sharp focus on what kind of households to add. The basic idea was high wealth, but that was not pushed exclusively at all Basically, AIMS wanted to do business with the same 2 million American households (over Si million in invested assets) that 21 other major financial services firms were pursuing SEGMENTATION AIMS spanned two separate and very different product lines (mutual funds and full-line brokerage services), but that was only one element of the complexity it faced. In addition to this product complexity, it also spanned three distinct "distribution channels" (Call Centers, Full Service Branches, and E-business), and a complex array of customers with diverse asset holdings, trading patterns, investment objectives and service requirements. There was no particularly sharp focus on what kind of households to add. The basic idea was high wealth, but that was not pushed exclusively at all. Basically, AIMS wanted to do business with the same 2 million American households (over $1 million in invested assets) that 21 other major financial services firms were pursuing. In 1999, AIMS introduced segment analysis, starting with a four-way segmentation that mixed three different dimensions: asset holdings, trading activity and age (as a proxy for investment objectives). The first segment was any household with more than $500,000 in assets under management at AIMS ("High Net Worth," or "HNW"). Failing this test, the second segment was households trading more than 36 times in 1998 ("Active Traders," or "AT"). Failing this test as well, the third segment was households where the principal customer was already retirement age 60 years old). Finally, customers failing all three of these tests comprised the fourth segment-all other, termed "Core" customers. *Core," with more than 70% of all households, was the largest segment. The primary role of any segmentation is to facilitate analysis leading to management actions tailored to the specific needs of defined customer subgroups. No particular segmentation is ever beyond dispute. Whatever approach is chosen necessarily emphasizes some distinctions and de- emphasizes others. But, the AIMS segmentation was particularly contentious on two grounds: 1) it segmented current customers rather than a market. It is as if Procter & Gamble were to segment the detergent market based on how many pounds of Tide are purchased; 2) the sequence specific classification scheme meant that labels could be misleading for example, the segment Active Trader applies only to households which are not each HNW. And, "Retiree applied only to households which were not each HNW or AT. FINANCIAL RESULTS As shown in Exhibit 1, AIMS did quite well in 1999. Net margin after tax was about $156 million on an underlying equity investment of about $625 million. But, 1999 represented the height of the prolonged bull market. The year 2000 was projected to be much less bullish, and most Wall Street observers envisioned the next few years to be much less rosy than the previous ten. Even in 1999, performance was not consistent across all the customer segments. Pre-tax margin ranged from a high of 48% for HNW, to only 6% for Retirees and minus 4% for Core, The revenue breakdown across segments in Exhibit 1 is based on actual identification with individual customers. The expense breakdown starts with an annual "unit cost" study that uses "Activity-Based Costing" (ABC) principles. The study first assigned all operating costs from the General Ledger to specific processes or activities." Then, the activity costs were divided by throughput measures for each activity, to create "cost per unit of activity" for each sub-stage of each process. This process is illustrated in Exhibit 2 for estimated costs for 2000. Individual unit costs were then multiplied by throughput totals for each segment and aggregated to provide total expenses per segment as shown in Exhibit I, a report format which was new at AIMS in 1999, Some of the assignments of costs to activities and some of the activity measures are "soft," but the activity costs tagged to individual households based on actual household activity are conceptually plausible and at least directionally correct. Similarly, product-specific and service-specific revenues are driven down to a household level. Household profitability calculations are thus based on actual asset holdings, fee-based services consumed and activity usage. The actual system in use allows for 11 categories of customer revenue and 70 categories of process cost, Conceptually. Exhibit 2 represents "long-run average cost" for each activity. It does not attempt to portray marginal or incremental cost because it is not intended for use in short-run cost-volume-profit (CVP) analyses. Since very little cost at AIMS is variable with short-run volume fluctuations anyway, short-run CVP analysis is really just based on revenue changes. Almost all costs are "step costs" which go up (or down), in chunks as capacity is added to (or deleted from) the system. In a business as fast-growing as AIMS has been in recent years, capacity is typically being added every year in many places across the process value chain ahead of usage requirements. Thus, there is almost always excess capacity in the system. And, the extent of excess capacity varies across processes, depending on where growth has been fastest and where recent expansions have been made. The analysis in Exhibit 2 divides current cost by current throughput to calculate unit cost. The analysis thus charges any excess capacity to the current users of the process. This is debatable, conceptually, but is not recognized as a practical problem at AIMS The expense base grew substantially faster than throughput volume between 1995 and 1999 anticipation of even greater future growth In 1995, there THE CUSTOMER/PRODUCT PROFITABILITY INITIATIVE As a management report, Exhibit I was too ageregated to identify actionable issues. In 2000, AIMS undertook a project to take customer product profitability reporting down to the individual household level to provide more uscable timely and integrated information for decision- NG 50 100% 2000 individun unit costs were then mutiplica by throughput totals for each segment and aggregated to provide total expenses per segment as shown in Exhibit 1, a report format which was new at AIMS in 1999. THE CUSTOMER/PRODUCT PROFITABILITY INITIATIVE As a management report, Exhibit I was too aggregated to identify actionable issues. In 2000, AIMS undertook a project to take customer/product profitability reporting down to the individual household level to provide more useable, timely, and integrated information for decision- making. The new system combined unit costs from the annual ABC study with current actual household activity and attributes (eg.. products held, services used, number of trades, number of rep-assisted phone calls) extracted from the Marketing Database to generate profitability by household. The data then were exported into easily queried online analytical processing (OLAP) "cubes." OLAP cubes allow profitability analysis of the intersections among customer attributes, product/service attributes, and channels of distribution. Exhibit 2, which illustrates the first step in this new system (unit costs across processes), is highly simplified for purposes of the case. As shown, a "driver" was chosen to proxy the activity in each process telephone calls as the driver of activity in the Call Center, for example. Next, a count was made of the total estimated units of the activity for 2000 for each driver 74.1 million calls for the Call Center, for example, Finally, the total cost for the process was divided by the total activity count to calculate cost per unit of activity for ahead of usage requirements. Thus, there is almost always excess capacity in the system. And, the extent of excess capacity varies across processes, depending on where growth has been fastest and where recent expansions have been made. The analysis in Exhibit 2 divides current cost by current throughput to calculate unit cost. The analysis thus charges any excess capacity to the current users of the process. This is debatable, conceptually, but is not recognized as a practical problem at AIMS. The expense base grew substantially faster than throughput volume between 1995 and 1999, in anticipation of even greater future growth. In 1995, there was about 10% excess capacity (on average) in the operating expense base. Capacity grew at a compound rate of about 26% from 1995 to 1999, versus households growth at about 21%. As a result, excess capacity in 1999 was a much larger percentage of the expense base, across branches, the call center, on-line activity, transactions processing and account maintenance activity. Kim wondered how much of operating capacity was devoted to unprofitable customers THE SEGMENTATION REFINEMENT INITIATIVE Another new initiative in 2000 to enhance customer profitability analysis involved further refining the segmentation. The goal was to better identify customer clusters that would be responsive to specific managerial actions. Kim Davis was chairing the task force coordinating this effort The primary four-way segmentation was expanded to 11 categories as shown below. that process High Net Worth (25500,000 of assets under management 1. (16,000 Households) >$2,000,000 in assets under management 2. (141,000 Households) - $500,000 to $2,000,000 Active Traders 36 trades per year 3. (9,000 Households) - more than 200 trades 4. (12,000 Households) - 60 to 200 trades 5. (19,000 Households) - 36 to 60 trades Retirees 6. (262,000 Households) - $100,000 to $500.000 in assets under management 7. (607,000 Households) $2,000,000 in assets under management 2. (141,000 Households) - $500,000 to $2,000,000 Active Traders 36 trades per year 3. (9,000 Households) - more than 200 trades 4. (12,000 Households) - 60 to 200 trades 5. (19,000 Households) - 36 to 60 trades Retirees 6. (262,000 Households) - $100,000 to $500.000 in assets under management 7. (607,000 Households)

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts