Question: Read Chapter 7 (Risk Management). Go over the cases two cases uploaded on Moodle (Dehavilland's Falling Comet and The Tacoma Narrows Suspension Bridge) and answer

Read Chapter 7 (Risk Management). Go over the cases two cases uploaded on Moodle (Dehavilland's Falling Comet and The Tacoma Narrows Suspension Bridge) and answer the following questions,

1. The process of risk identification can involve risk classification for likely risks. Note that risk classifications include financial risk, technical risk, commercial risk, execution risk, Which risk classifications are the most relevant for each of the cases?

2. Go over Tables 7.1 and 7.2 Determining Likely Risks and Consequences and Calculating a Project Risk Factor. Provide a score for each of the two cases. Justify your score for each category in Table 7.2.

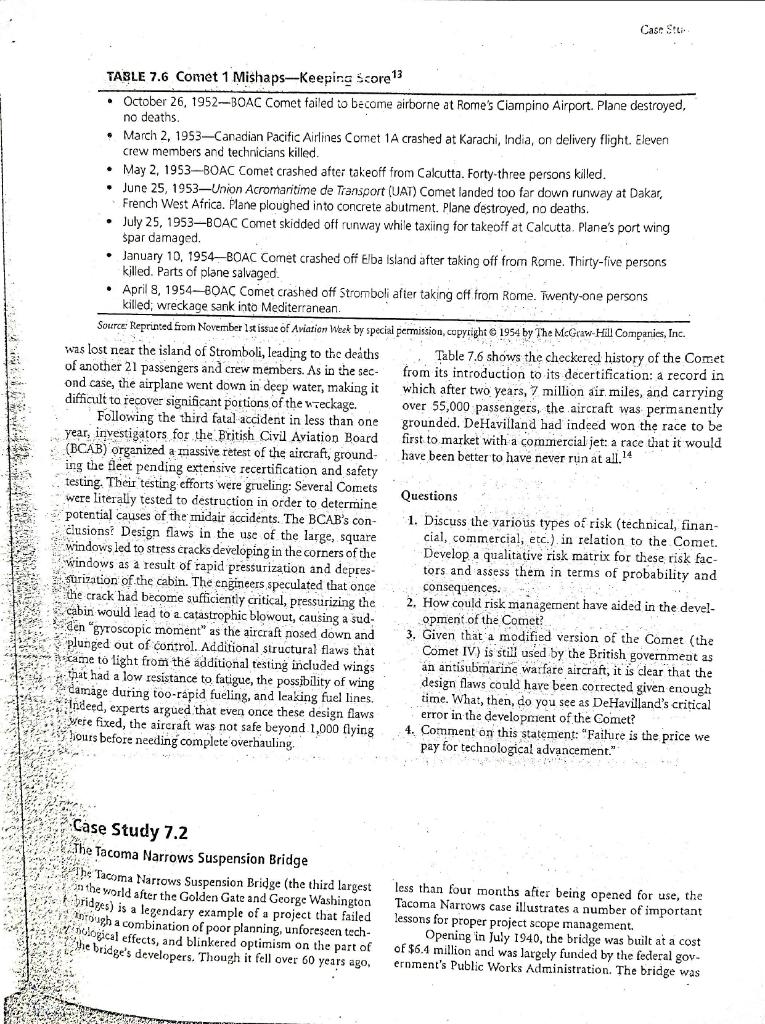

Case Study 7.1 De Havilland's Falling Comet Following World War II, De Havilland had been locked in a battle with Boeing Corporation to see which company could be the first to market with a jet-powered airplane to take advantage of the burgeoning commercial airline market. De Havilland's entry, the Comet (shown in Figure 7.9), won the race and was introduced in 1952, well ahead of the Boeing 707 model. The Comet was clearly a landmark aircraft for its day; featuring a fully pressurized cabin, a well-designed interior, large, square- shaped windows, and engines embedded in the wings, it was a trend-setter in every sense. When the Comet was offered commercially, De Havilland could not help but feel that it had the inside track on a market with enor- mous profit potential. Troubles began quickly after the airplane was intro- duced and taken into service by, among other airlines, the British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC). In May of 1953, a Comet broke apart in a storm and was lost 22 miles from Calcutta's airport, killing all 43 passengers and crew on board. The preliminary assessment of the cause of the crash was listed as pilot error coupled with weather condi- tions." No further action was taken. On January 10, 1954, 35 passengers and crew members of another Comet took off from Rome's Ciampino Airport for London. Just as the airplane reached its cruising altitude and speed, it disinte- grated over the Mediterranean, near the island of Elba. In the wake of this second midair disaster, the aircraft were taken out of service by BOAC for recertification test- ing. Following a brief examination, the aircraft were again deemed airworthy and reintroduced to the airline's fleet. In April, only 16 days after the reintroduction, a third Comet, also taking off from Rome but on its way to Johannesburg, FFURE 7.9 The DeHavilland Comet TABLE 7.6 Comet 1 Mishaps-Keeping Score 13 October 26, 1952---BOAC Comet failed to become airborne at Rome's Ciampino Airport. Plane destroyed, no deaths March 2, 1953-Canadian Pacific Airlines Comet 1A crashed at Karachi, India, on delivery flight. Eleven crew members and technicians killed. May 2, 1953-BOAC Comet crashed after takeoff from Calcutta. Forty-three persons killed. June 25, 1953Union Acromaritime de Transport (UAT) Comet landed too far down runway at Dakar, French West Africa. Plane ploughed into concrete abutment. Plane destroyed, no deaths. July 25, 1953-BOAC Comet skidded off runway while taxiing for takeoff at Calcutta. Plane's port wing Spar damaged. January 10, 1954--BOAC Comet crashed off Elba Island after taking off from Rome. Thirty-five persons killed. Parts of plane salvaged. April 8, 1954-BOAC Comet crashed off Stromboli after taking off from Rome. Twenty-one persons killed; wreckage sank into Mediterranean. Source: Reprinted from November 1st issue of Aviation Week by special permission, copyright 1954 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. was lost near the island of Stromboli, leading to the deaths Table 7.6 shows the checkered history of the Comet of another 21 passengers and crew members. As in the sec from its introduction to its decertification: a record in ond case, the airplane went down in deep water, making it which after two years, 7 million air miles, and carrying difficult to recover significant portions of the wreckage. over 55,000 passengers, the aircraft was permanently Following the third fatal accident in less than one grounded. DeHavilland had indeed won the race to be year, investigators for the British Civil Aviation Board first to market with a commercial jet: a race that it would (BCAB) organized a massive retest of the aircraft, ground have been better to have never run at all.14 ing the fleet pending extensive recertification and safety testing. Theis testing efforts were grueling: Several Comets Questions were literally tested to destruction in order to determine potential of the midair accidents. The BCAB's con 1. Discuss the various types of risk (technical, finan- clusions Design flaws in the use of the large, square cial, commercial, etc.), in relation to the Comet. Windows led to to stress cracks developing in the corners of the Develop a qualitative risk matrix for these risk fac- windows as a result of rapid pressurization and depres tors and assess them in terms of probability and urization of . The the crack had become sufficiently critical, pressurizing the neers speculated that once consequences. 2. How could risk management have aided in the devel- cabin would lead to ein lead to a catastrophic blowout, causing a sud opment of the Comet? den syroscopic moment" as the aircraft nosed down and 3. out of control. Additional structural flaws that Given that a modified version of the Comet (the came to light from the additional testing included wings Comet IV) is still used by the British government as an antisubmarine warfare aircraft, it is clear that the that had a low resistance to fatigue, the possibility of wing damage during too-rapid fueling, and leaking fuel lines . design flaws could have been corrected given enough time. What, then, do you see as De Havilland's critical Indeed, experts argued that even once these design flaws error in the development of the Comet? were fixed, the aircraft was not safe beyond 1,000 flying 4. Comment on this statement: "Failure is the price we by hours before needing complete overhauling, pay for technological advancement." causes of his Case Study 7.2 The Tacoma Narrows Suspension Bridge he Tacoma Narrows Suspension Bridge (the third largest on the world after the Golden Gate and George Washington bridges) is a legendary example of a project that failed tough a combination of poor planning, unforeseen tech- iogical effects, and blinkered optimism on the part of the bridge's developers. Though it fell over 60 years ago, less than four months after being opened for use, the Tacoma Narrows case illustrates a number of important lessons for proper project scope management. Opening in July 1940, the bridge was built at a cost of $6.4 million and was largely funded by the federal gov. ernment's Public Works Administration. The bridge was 242 Chapter 7 . Risk Management intended to connect Seattle and Tacome Puget Sound Navy Yard at Bremerton, Washington. It ada cen- ter span of 2,800 feet and 1,000-foot approaches at each end. Interestingly, the bridge was designed for only one lane of traffic in each direction, making it not only very long but also very narrow. Even before its inauguration and opening, the bridge exhibited strange characteristics that were immediately noticeable. For example, the slightest wind could cause the bridge to develop a pronounced longitudinal roll. The bridge would quite literally begin to lift at one ead and in a wave action, and the lift would "roll" the length of the bridge. Depending upon the severity of the wind, cameras were able to detect anywhere up to eight separate vertical nodes in its rolling action. Many motorists crossing the bridge complained of acute seasickness brought on by the bridge's rising and falling! So well known to the locals did the strange motion of the bridge become that they nicknamed the bridge "Galloping Gertie." On November 7, 1940, a bare four months after the bridge was opened, with steady winds of 42 miles per hour, the 2,800-foot main span, which had already begun exhibiting a marked flex, went into a series of violent ver- tical and forsional oscillations. The amplitudes steadily increased, suspensions came loose, the support structures buckled, and the span began to break up. In effect, the bridge had seemed to come alive, struggling like a bound animal, and was literally shaking itself apart. Motorists caught on the bridge abandoned their cars and crawled off the bridge as the side-to-side roll had become so pro- nounced (by now, the rol had reached 45 degrees in either direction, causing the sides of the bridge to rise and fall over 30 feet) that it was impossible to walk. After a fairly short period in which the wave oscillations became incredibly violent, the suspension bridge simply could not resist the pounding and broke apart. Observers stood in shock near the bridge and watched as first large pieces of the roadway, and then entire lengths of the span rained down into the Tacoma Narrows. Fortunately, no lives were lost, since traffic had been closed just in time. A three-p e-person committee of scientists was imme- diately convened to determine the causes of the Tacoma Narrows collapse. The board consisted of some of the top scientists and engineers in the world at that time: Othmar Ammann, Theodore von Karman, and Glenn Woodruff. While satisfied that the basic design was sound and the suspension bridge had been constructe competently, they nevertheless were able to quickly uncover the under- lying contributing causes of the bridge collapse First, the physical construction of the bridge con- tributed directly to its failure and was a source of continu- al concern from the time of its completion. Unlike other suspension bridges, one distinguishing feature of the Tacoma Narrows bridge was its small width-to-length ratio-smaller than any other suspension :: type in the world. That ratio means that the bridge was incredibly narrow for its long length, a fact that con- tributed hugely to its distinctive oscillating behavior. Although almost one mile long, the bridge carried only a single traffic lane in each direction. Another feature of the construction that was to play an important role in its collapse was the substitution of key structural components. The chief engineer in charge of con- struction, Charles Andrews, noted that the original plans called for the use of open girders in the bridge's sides. At some point, a local construction engineer substituted flat, solid girders, which deflected the wind rather than allowing it to pass. The result, Andrews noted, was that the bridge caught the wind like a kite" and adopted a permanent sway. In engineering terms, the flat sides simply would not allow wind to pass through the sides of the bridge, which would have reduced its wind drag. Instead, the solid, flat sides caught the wind, which pushed the bridge sideways until it swayed enough to "spill" the wind from the vertical plane, much as a sailboat catches and spills wind in its sails. A final problem with the initial plan lay in the loca- tion selected for the bridge's construction. The topography of the Tacoma Narrows is particularly prone to high winds due to the narrowing of the valley along the waterway. As a local engineer suggested, the unique characteristics of the land on which the bridge was built virtually doubled the wind velocity and acted as a sort of wind tunnel. Before this collapse, not much was known about the effects of dynamic loads on structures. Until then, it had always been taken for granted in bridge building that static (vertical) load and the sheer bulk and mass of large structures were enough to protect them against wind effects. It took this disaster to firmly establish in the minds of design engineers that dynamic and not static loads are really the critical factor in designing such structures. 15 Questions 1. In what ways were the project's planning and scope management appropriate? When did the planners begin taking unknowing or unnecessary risks? Discuss the issue of project constraints and others. unique aspects of the bridge in the risk management process. Were these issues taken into consideration? Why or why not? 2. Conduct either a qualitative or quantitative risk as.. sessment on this project. Identify the risk factors that you consider most important for the suspension bridge construction, How would you assess the riski ness of this project? Why? 3. What forms of risk mitigation would you consider appropriate for this projectStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts