Question: Read teaching and learning with infants and toddlers by Mary Jane maguire fong and an reflection on chapter 8 on your thoughts on it this

Read teaching and learning with infants and toddlers by Mary Jane maguire fong and an reflection on chapter 8 on your thoughts on it this should include the main ideas and supporting details from the book

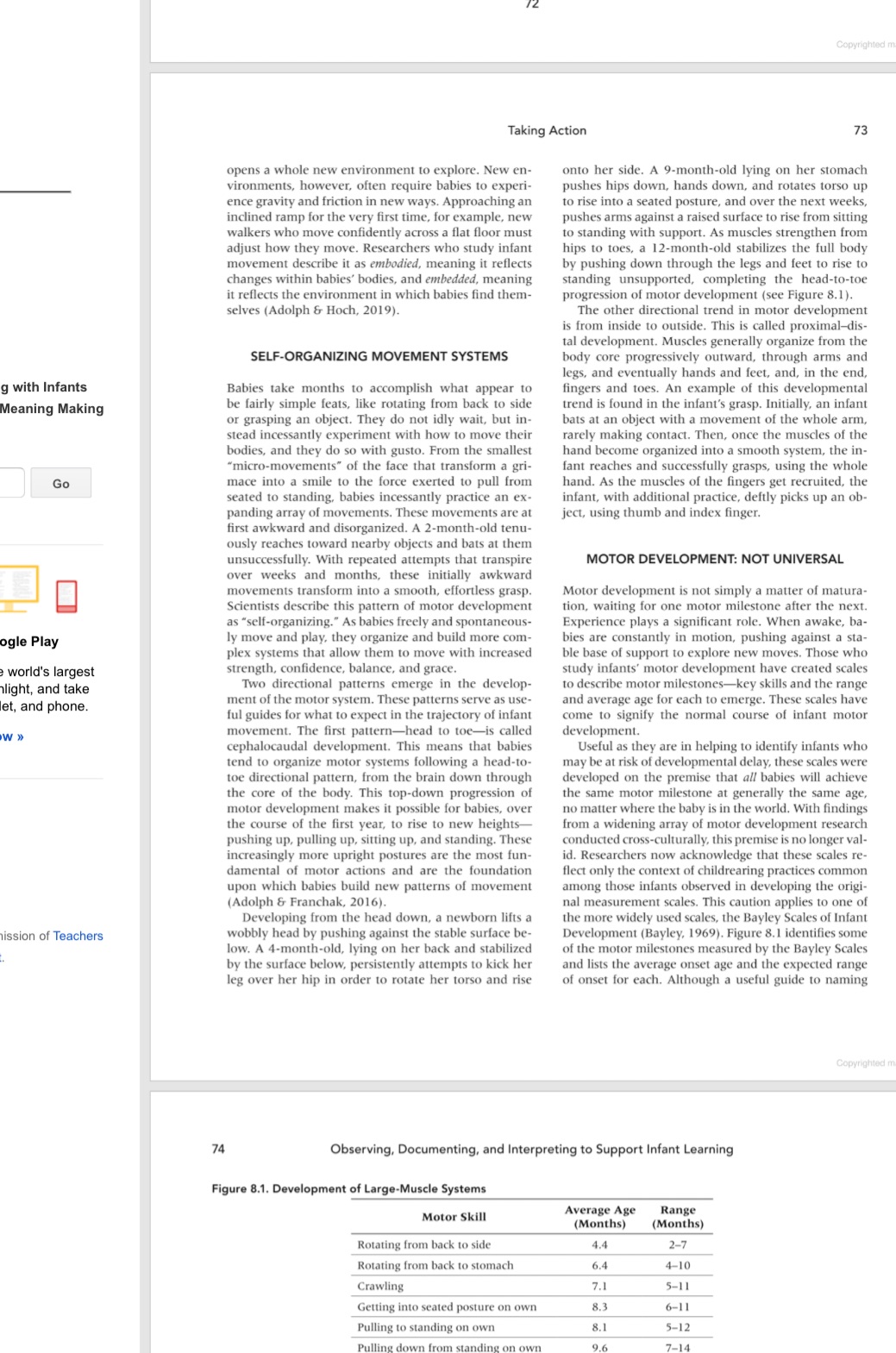

lable .com earning with Infants Where Meaning Making re-Fong ook Go |0 on Google Play rom the world's largest ad, highlight, and take eb, tablet, and phone. 'lay Now Taking Action Motor Development In the course of her motor development, a baby . . . learn[s] how to turn over onto her belly, to roll over, crawl, sit, stand and walk, [but] she also learns how to learn. She learns to tackle something on her own, to take interest in something, to try something out, to experiment. She learns to overcome difficulties. She experiences the joy and the satisfaction that comes with success, the result of her patience and perseverance. (Pikler, 1994, p. 16) BABY ROLLS OVER for the very first time and is greeted with cheers of delight. Although a cause for celebration, the more fascinating story is what oc- curred in the weeks prior to this new move, The study of infant movement is more than just a list of motor milestones. It is a window into babies' ways of making meaning about their bodies in relation 1o the world around them. This chapter describes the progression of maotor development in infancy, but more important, it explores infants' incessant quest to move with stabili- ty, balance, strength, conlidence, and grace, and what teachers and families can do to support them along the way, within the three contexts for learningplay spaces, daily routines, and everyday conversations and interactions. During infancy, babies experience a cascade of changes with respect to how they move and how they act on the world they encounter. An 18-month-old synchronizes muscles of the face and jaw to eat and to speak, effortlessly moves through a clutter of objects in the play space, crawls under a chair and up a series of stairs, moves objects in and out of places with ease, throws balls with vigor, gently touches a wiggly worm, and meticulously picks up tiny pebbles. In the short span of a year and a hall, infants develop an amazing variety of fluid movements, and they do this within a context of continual change, described by researchers Adolph and Robinson (2013} as \"learning to move and moving to learn\" (p. 113). Newborns arrive with a package of innate move- ments called reflexesmovements that occur without conscious intention or planning. Blinking is an exam- ple of a reflex that remains throughout life, but other reflexes, known as infantile reflexes, are temporary and appear to help newborns stay closely connected 72 10 the nurturing adult. An object touching the new- born's palm, for example, results in the fingers closing tightly around the object, and a sudden drop in the newborn's head position or a loud sound nearby elicits a sudden flexion of arms and legs, clutching inward. Over the course of the first few months, in typically developing infams, infantile reflexes become less evi- dent, replaced by voluntary actions. Movements, even those that involve simple actions like lifting a cup to drink, involve continuous cycles of information being relayed among the brain, the muscles, and the surrounding environment. As babies grow in size, so does the brain, and these changes bring new possibilities for movement and action, which Research Highlight: Newborns Reflexively Seek Nourishment In an unmedicated birth, a newborn baby, placed on the mother's abdomen, will inch reflexively and gradually to the mother's breast, pushing alternately with the feet in a reflexive stepping pattern (Widstrom et al., 1987). When the baby's cheek touches the mother's breast, the baby will turn in the direction of the touch, as if going in search of the nipple, a reflexive action called rooting. As the baby's lips touch the nipple, the baby's sucking reflex is triggered, pulling milk into the mouth. As the milk hits the back of the mouth, the baby reflexively swallows. These infant reflexes ensure that babies have the nourishment they need to survive outside the womb. g with Infants Meaning Making Go O ogle Play r world's largest Wight, and take let, and phone. W rission of Teachers Taking Action 73 opens a whole new environment to explore. New en- vironments, however, often require babies to experi- ence gravity and friction in new ways. Approaching an inclined ramp for the very first time, for example, new walkers who move confidently across a flat floor must adjust how they move. Researchers who study infant movement describe it as embodied, meaning it reflects changes within babies' bodies, and embedded, meaning it reflects the environment in which babies find them- selves (Adolph & Hoch, 2019). SELF-ORGANIZING MOVEMENT SYSTEMS Babies take months to accomplish what appear to be fairly simple feats, like rotating from back 1o side or grasping an object. They do not idly wait, but in- stead incessantly experiment with how 1o move their bodies, and they do so with gusto. From the smallest \"micro-movements\" of the face that transform a gri- mace into a smile to the force exerted o pull from seated to standing, babies incessantly practice an ex- panding array of movements. These movements are at first awkward and disorganized. A 2-month-old tenu- ously reaches toward nearby objects and bats at them unsuccessiully. With repeated attempts that transpire over weeks and months, these initially awkward movements transform into a smooth, effortless grasp. Scientists describe this pattern of motor development as \"self-organizing.\" As babies freely and spontaneous- ly move and play, they organize and build more com- plex systems that allow them o move with increased strength, confidence, balance, and grace. Two directional patterns emerge in the develop- ment of the motor system. These patterns serve as use- ful guides for what to expect in the trajectory of infant movement. The first patternhead 1o toeis called cephalocaudal development. This means that babies tend to organize motor systems following a head-1o- toe directional pattern, from the brain down through the core of the body. This top-down progression of motor development makes it possible for babies, over the course of the first year, to rise to new heights pushing up, pulling up, sitting up, and standing. These increasingly more upright postures are the most fun- damental of motor actions and are the foundation upon which babies build new patterns of movement {Adolph & Franchak, 2016). Developing from the head down, a newborn lifts a wobbly head by pushing against the stable surface be- low. A 4-month-old, lying on her back and siabilized by the surface below, persistently attempts to kick her leg over her hip in order to rotate her torso and rise onto her side. A 9-month-old lying on her stomach pushes hips down, hands down, and rotates torso up to rise into a seated posture, and over the next weeks, pushes arms against a raised surface to rise from sitting to standing with support. As muscles strengthen from hips to twes, a 12-month-old stabilizes the full body by pushing down through the legs and feet to rise to standing unsupported, completing the head-to-toe progression of motor development (see Figure 8.1). The other directional trend in motor development is from inside to outside. This is called proximal-dis- tal development. Muscles generally organize from the body core progressively outward, through arms and legs. and eventually hands and feet, and, in the end, fingers and 1oes. An example of this developmental trend is found in the infant's grasp. Initially, an infant bats at an object with a movement of the whole arm, rarely making contact. Then, once the muscles of the hand become organized into a smooth system, the in- fant reaches and successfully grasps, using the whole hand. As the muscles of the fingers get recruited, the infant, with additional practice, defily picks up an ob- ject, using thumb and index finger. MOTOR DEVELOPMENT: NOT UNIVERSAL Motor development is not simply a matter ol matura- tion, waiting for one motor milestone after the next. Experience plays a significant role. When awake, ba- bies are constantly in motion, pushing against a sta- ble base of support 10 explore new moves, Those who study infants' motor development have created scales to describe motor milestoneskey skills and the range and average age for each to emerge. These scales have come to signify the normal course of infant motor development. Useful as they are in helping to identify infants who may be at risk of developmental delay, these scales were developed on the premise that all babies will achieve the same motor milestone at generally the same age, no matter where the baby is in the world. With findings from a widening array of motor development research conducted cross-culturally, this premise is no longer val- id. Researchers now acknowledge that these scales re- flect only the context of childrearing practices common among those infants observed in developing the origi- nal measurement scales. This caution applies to one of the more widely used scales, the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (Bayley, 1969). Figure 8.1 identifies some of the motor milestones measured by the Bayley Scales and lists the average onset age and the expected range of onset for each. Although a useful guide to naming Observing, Documenting, and Interpreting to Support Infant Learning Figure 8.1. Development of Large-Muscle Systems Motor Skill Average Age Range {Months) (Months) Rotating from back to side Crawling Getting into seated posture on own Pulling 1o standing on own Pulling down from standing on own 4.4 2-7 6.4 4-10 7.1 s-11 83 6-11 8.1 5-12 9.6 7-14 and tracking some of the commonly referenced motor [An infant dedicates himself] with extraordinary inter- skills, it is important to keep in mind that motor devel- est and amazing patience. He attentively studies one opment happens within a social and physical environ- movement innumerable times. He enjoys and becomes on Google Play ment, and that how babies learn to move and when is absorbed in each little detail, each nuance of a move- a function of where they find themselves, with whom, ment, quietly taking his time in an experimenting mode. rom the world's largest and with what expectations. Perhaps it is the very repetitiveness of this study that ad, highlight, and take Cross-cultural studies (Adolph, Karasik, & Tami- brings such delight to a child. During the first two years, eb, tablet, and phone. LeMonda, 2009; Karasik, Ossmy, Tamis-LeMonda, & she is busy-or better, she is "playing"-with each move- Adolph, 2018) show clearly that motor development ment for days, weeks, sometimes months. Each move- Play Now >> is not universal. Although milestone charts suggest an ment has its own history of development. Each one is orderly march through a series of stages defined by based upon the other. (p. 12) onset ages, babies' path of motor development var- ies, and individual infants do not strictly adhere to Pikler emphasized the importance of babies be- the normative sequence. The order in which infants ing free to move, and demonstrated through her acquire skills varies, some infants skip a stage, and research that time spent in self-initiated practice re- many revert to earlier forms of movement (Adolph & sults in balance, confidence, and grace in posture and Franchak, 2016). movement. When free to move, to experiment, to try and fail, to try again, to test a variation, and to slowly and surely reach a posture of balance and grace, in- WHEN FREE TO MOVE fants thrive. Motor milestone charts also fail to describe the won- Rotating Up by permission of Teachers derful effort and work that transpire in the period lead- ing up to the attainment of each milestone. Hungarian Newborns, rested and free from hunger, will lie on opyright. pediatrician Emmi Pikler (2006) made this point when their back with legs and arms bent, with head turned she recorded in great detail infants' transformation of slightly to the side, a posture determined by the tonic postures from back to stomach, from creeping on belly neck reflex, which keeps the baby's head turned in to crawling, to sitting up, to pulling to standing, and the direction of the outstretched arm. Within weeks, to walking. She studied babies' spontaneous efforts this reflex disappears. As they lie on their back, new- to get into a posture, to achieve balance in that pos- borns move their arms and legs in motions that are ture, and eventually to master moving into and out at first erratic and choppy. As days pass, these move- of that posture with ease and grace. She observed as ments self-organize into smooth, rhythmic patterns, babies moved freely within thoughtfully designed play and they begin to lift parts of the body from the sup- spaces. Her records of motor development show a pur- port surface (Adolph & Franchak, 2016). Using a poseful sequence of movement transformations, with corkscrew-like move, they put great effort into rotat- one movement giving rise to another, as babies active- ing the body up onto the side, persistently attempting ly experiment with how to use their bodies. As Pikler to throw top leg over pelvis to tilt up onto the side (1994) explained: (Figure 8.2). Copyrighted m Taking Action 75Taking Action 75 Figure 8.2. Rotating from Back to Side This is a challenging move, but one that opens new vistas. Rotated onto their side, babies have a whole new perspective on their surroundings. They tense their full body to stay balanced in this side position. To relax and rest, they return to their back, but soon will return to balancing once again on their side. With repeated tries, their balance improves, and as illusirated in Figure 8.2, they can stay on their side for long periods of time (Pikler, 1988). According to the Bayley Scales, on aver- age, babies turn from back to side at 4.4 months, and do so as early as 2 months and as late as 7 months. Babies who have learned to turn from back 1o side are content to play on their side for weeks. On av- erage, 8 weeks will pass between the point when a baby learns to rotate from back to side to the point Reflection: Rolling Over What Does It Take? Compare the difference in average age for turning from back to side and average age for turning completely over from back to stomach. Then consider the kinds of furnishings and equipment marketed for babies of this age. Reflect on what the baby experiences when confined to a rigid seat, unable to move legs, arms, torso, and hips freely. Does such equipment support movement during this period or impede it? With this in mind, what would you recommend for designing a play space for babies who are between 2 and 10 months of age? when the baby masters rotating all the way over, from back to stomach. The average age for rotating from back to stomach is 6.4 months, within a range of 4-10 maonths of age, Once babies accomplish rotating fully from back to stomach, they often choose to spend in- creasing amounts of time lying on their stomach in a prone position. This gives them an opportunity to ex- periment with lifting the head, then using hands and arms to lift the torso. Sitting Up As infants extend and lift the torso while lying sup- ported on a stable base, they elongate and straighten the spine, movements that are important for postural control in an upright position, be it sitting, crawling, or standing (Adolph & Franchak, 2016; Pikler, 1988, 2006). These movements prepare infants to push up against gravity with enough force to rise into an un- supported seated position. They do this by rotating onto the side, then throwing the upper leg over the pelvis, while at the same time pushing down with an arm to prop themselves into a half-seated posture. With a stronger push of the arm, they lift the torso to a fully seated posture. This self-initiated movement brings the whole room into view and opens entirely new vistas. Pulling to an unsupported sitting posture occurs within a range of 6-11 months, and on average at 8.3 months (Bayley, 1969). Reflection: Sitting UpPropped or Free to Move? Observe a young baby who has been propped in a seated position. Most likely, you will see a curved spine, rather than an erect spine. The weight of the baby's body centers on the tailbone, rather than the buttock, forcing the baby to curve the spine unnaturally forward in order to resist falling backward. The baby's chest sags inward, compacting the lungs and other organs. Bones and muscles are misaligned. For a baby who cannot yet get into a seated posture on his own, sitting is a strain, even when propped. Some argue that babies enjoy being propped in a seated position. What advantages or disadvantages do you see of babies being propped to sit? What impact might this have on the muscle systems that organize in preparation for crawling or pulling to standing? 76 Observing, Documenting, and Interpreting to Support Infant Learning Pikler (1988) and Gerber (1998) urge caregivers to let babies get into seated or standing positions on their own. They discourage caregivers from propping babies in seated positions or holding them in standing positions if the babies cannot yet get into that posi- tion independently. Pikler notes that babies who get o a snated ool - e - mwnen vkl masialides ad to stand unsupported. Notice how this involves more effort of the hips, legs, and feet. The act of lowering to the ground is largely the work of the leg muscles, which are still organizing. The average age for independently getting down from = dn manmsbha (T asd o a vt ad atam