Question: Read the MacLeod Case Examples that is listed below and write about it concerning ergonomics. What surprised you (if anything)? What did you learn from

Read the MacLeod Case Examples that is listed below and write about it concerning ergonomics. What surprised you (if anything)? What did you learn from this case?

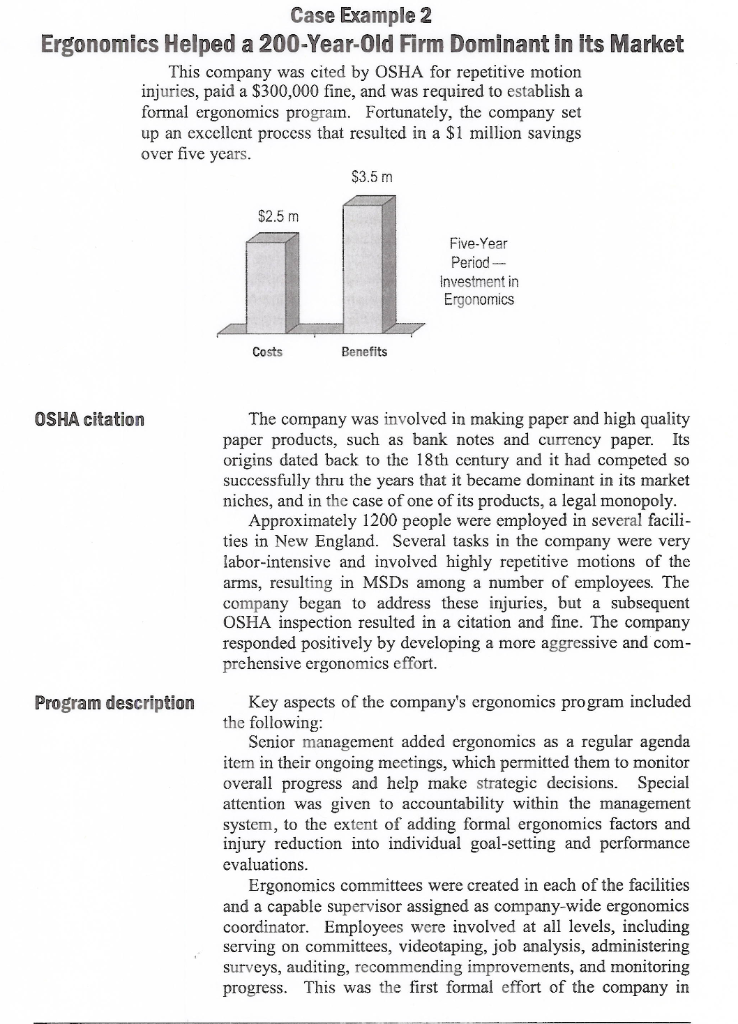

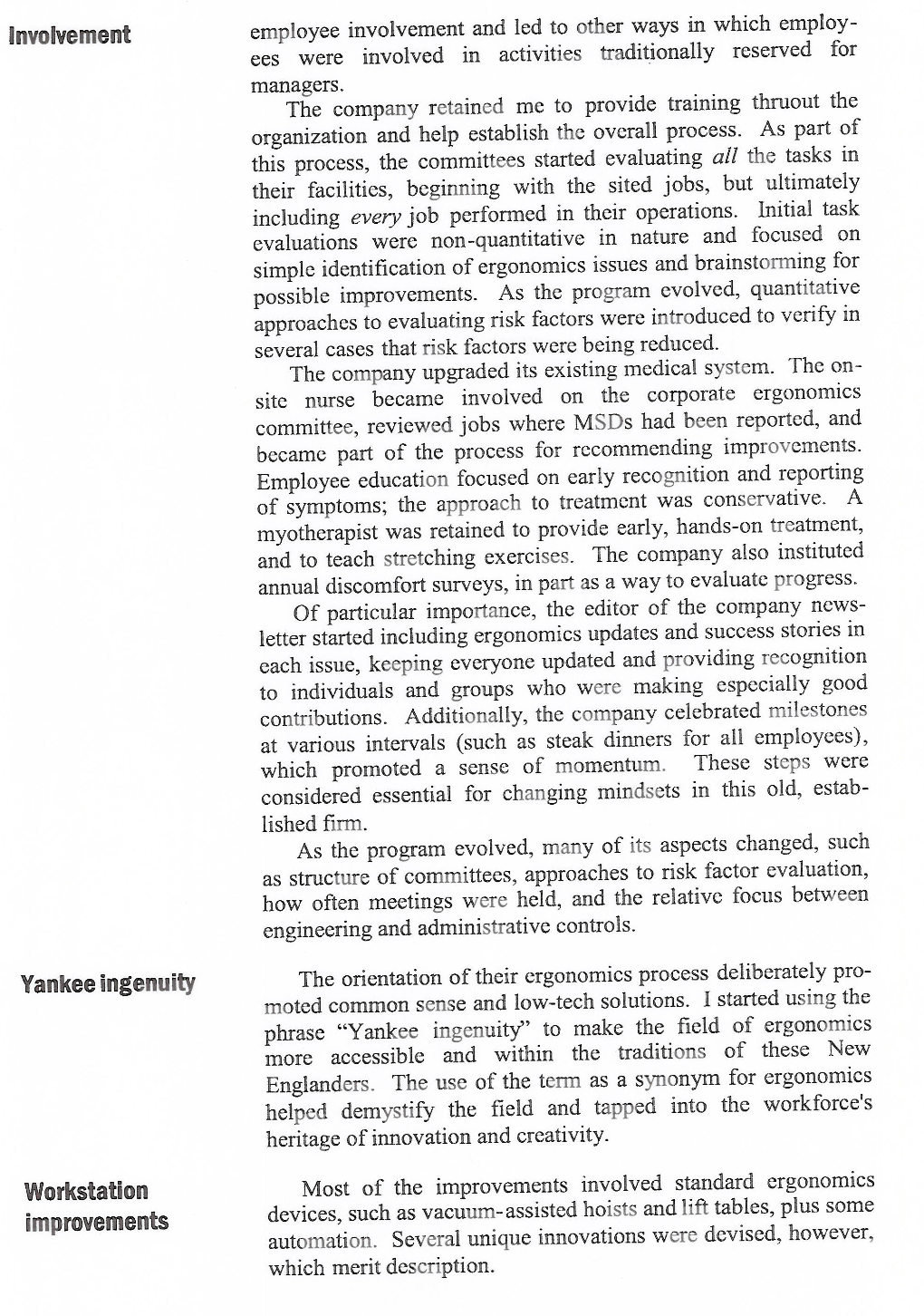

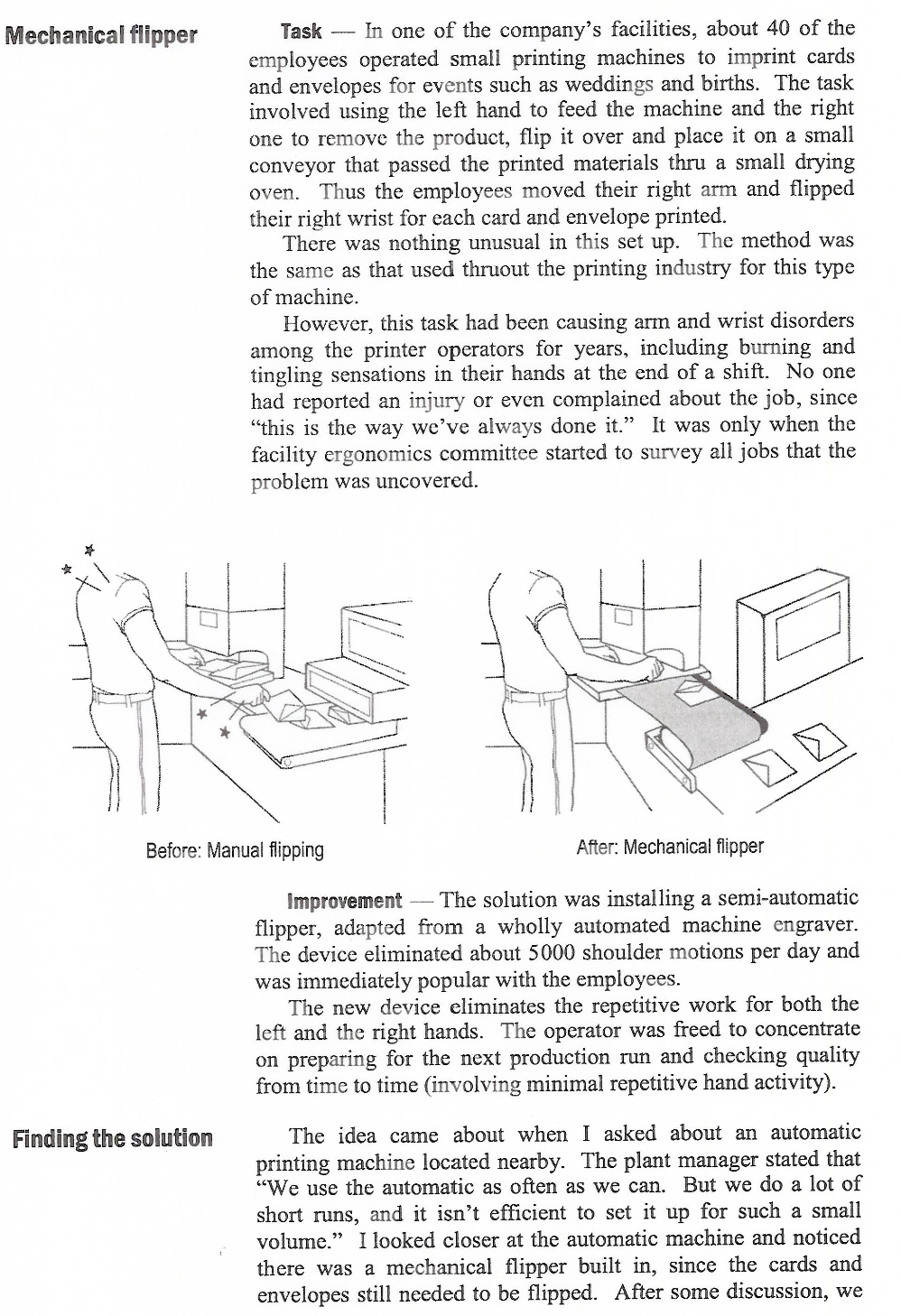

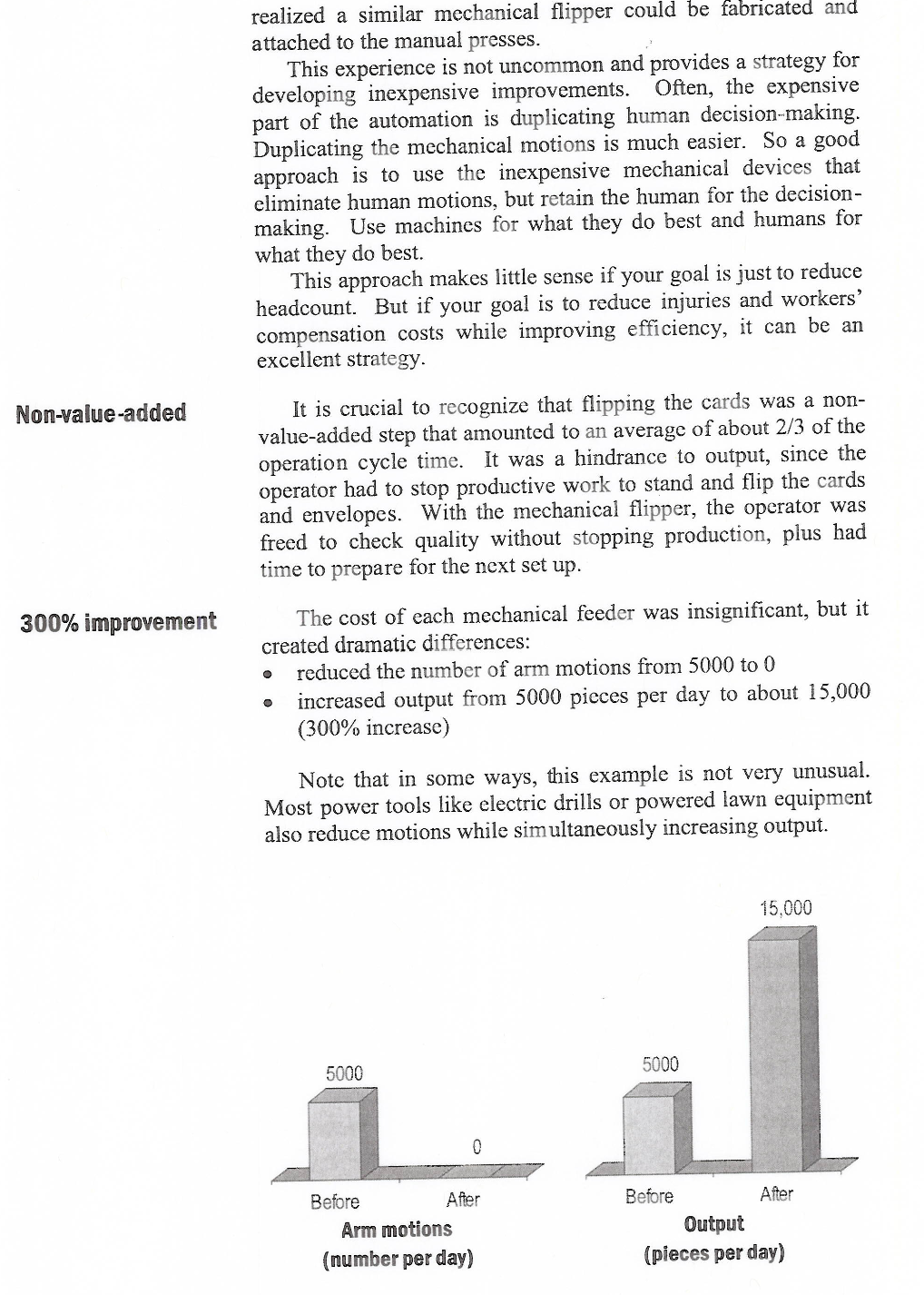

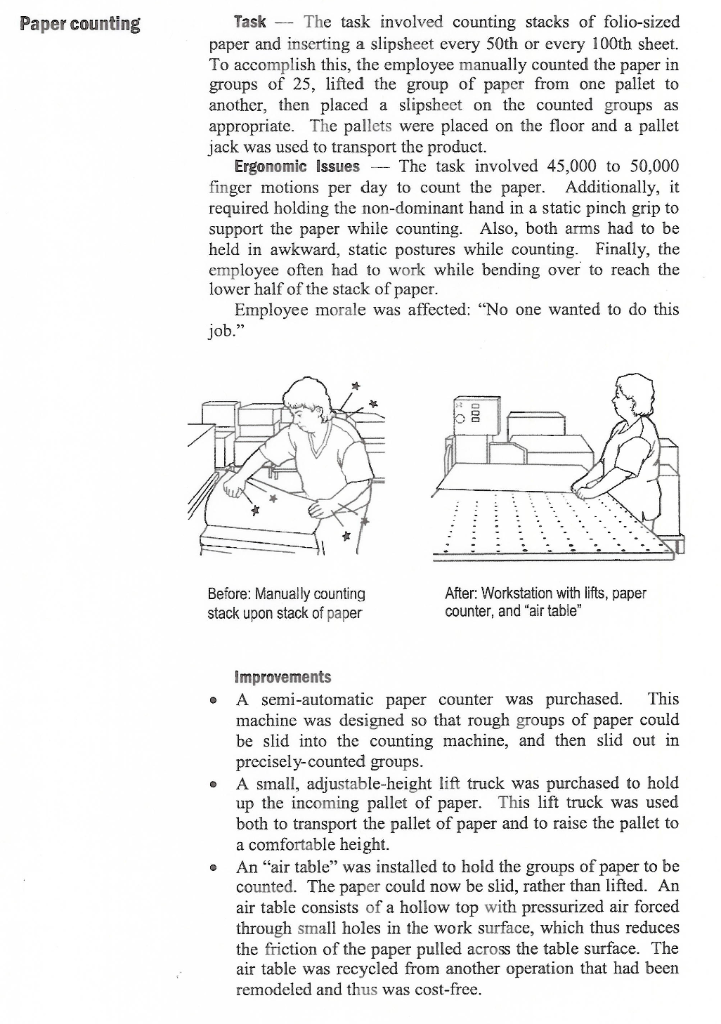

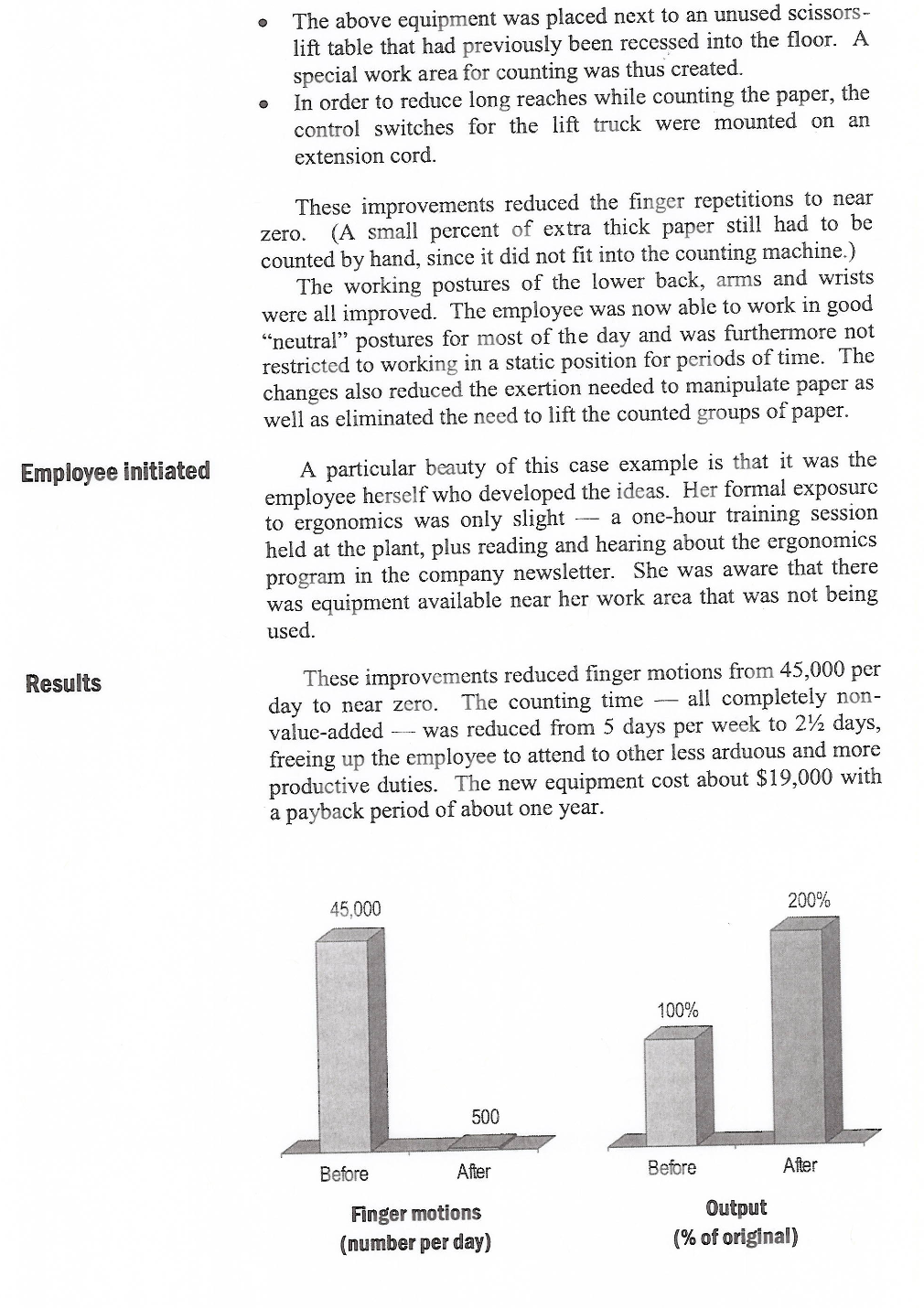

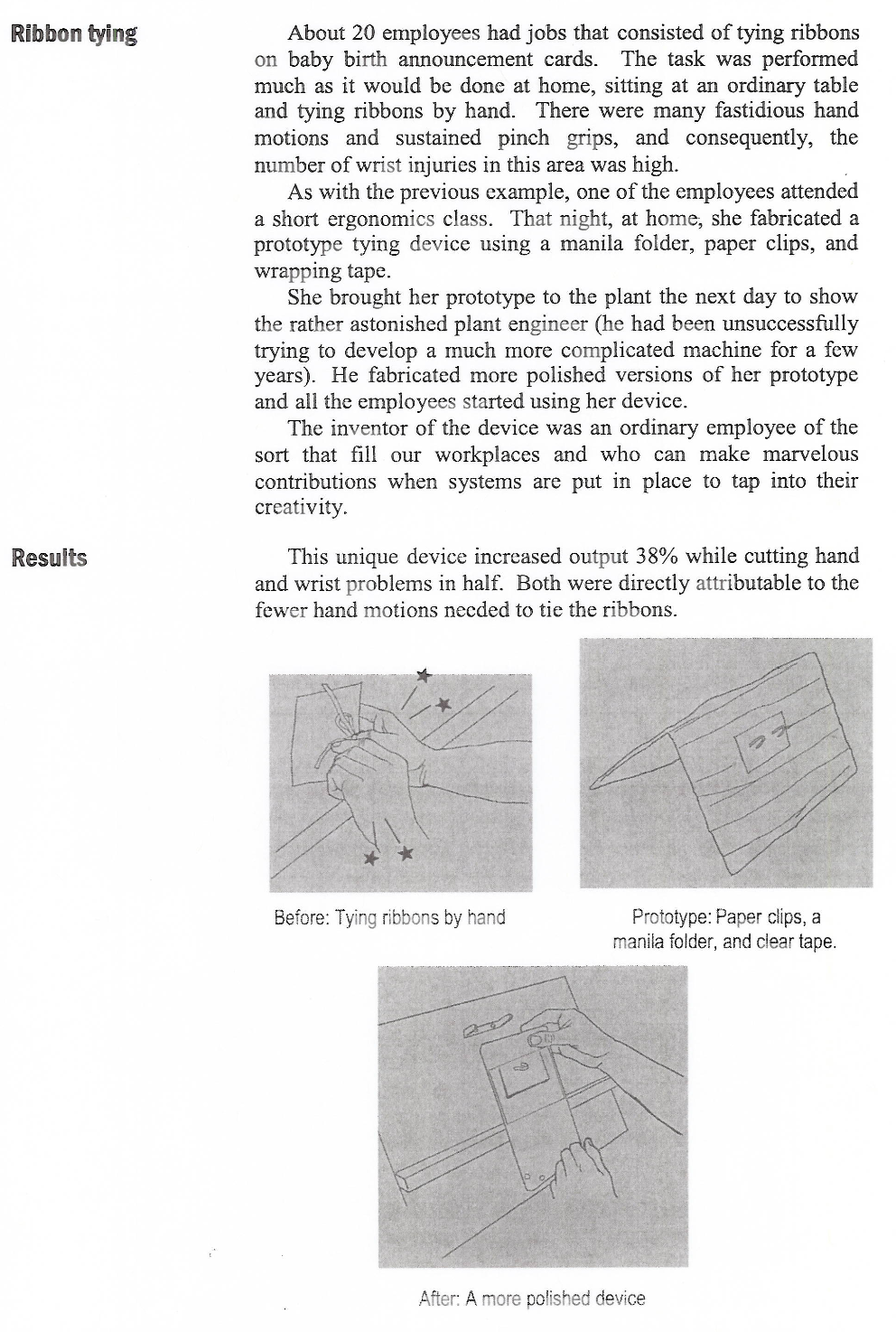

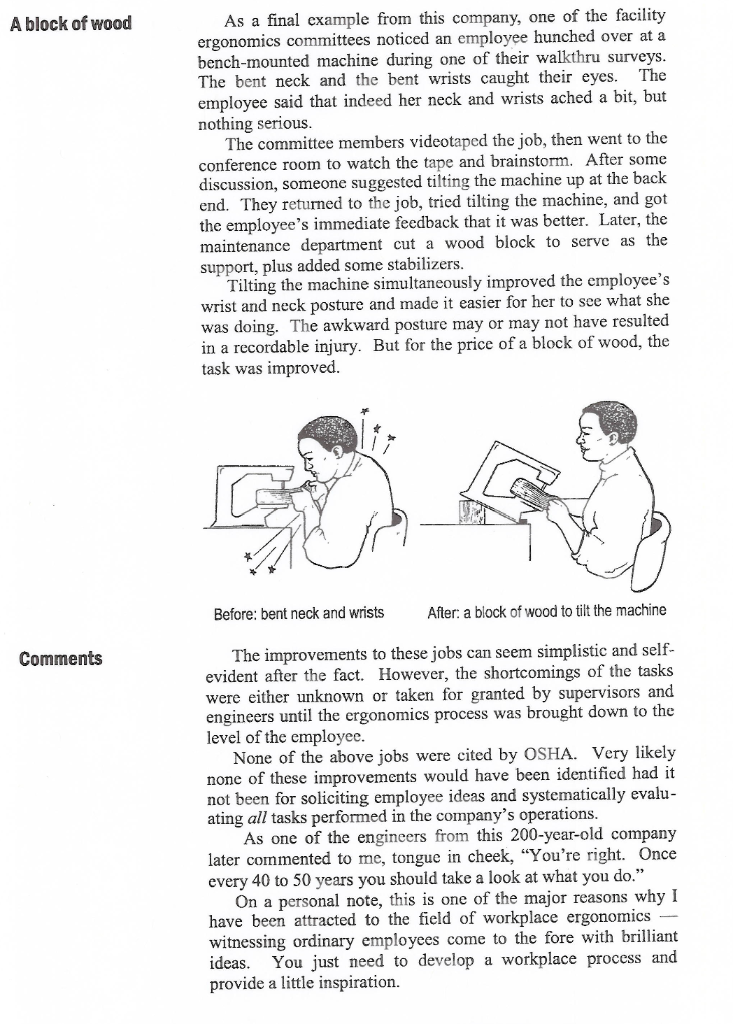

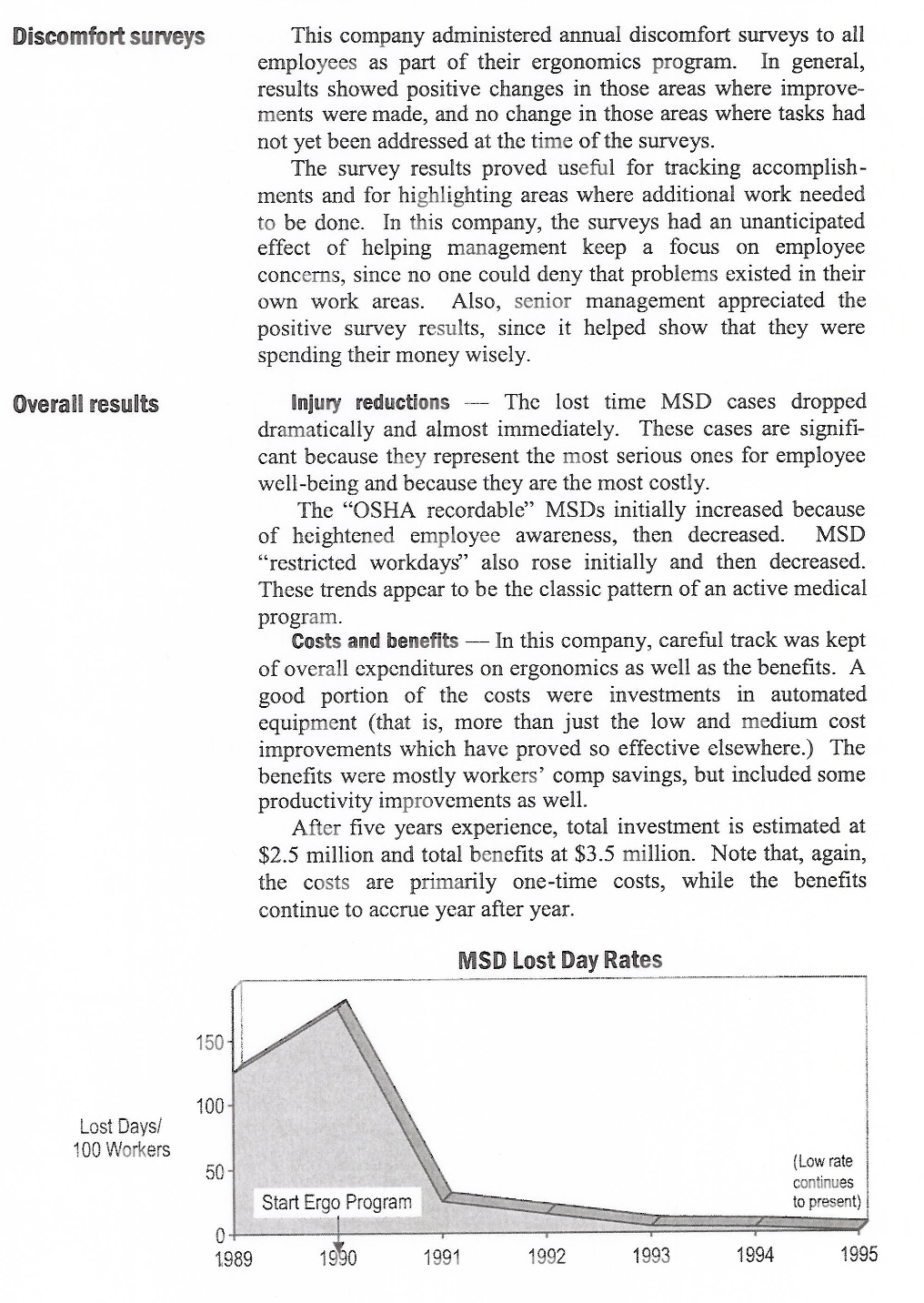

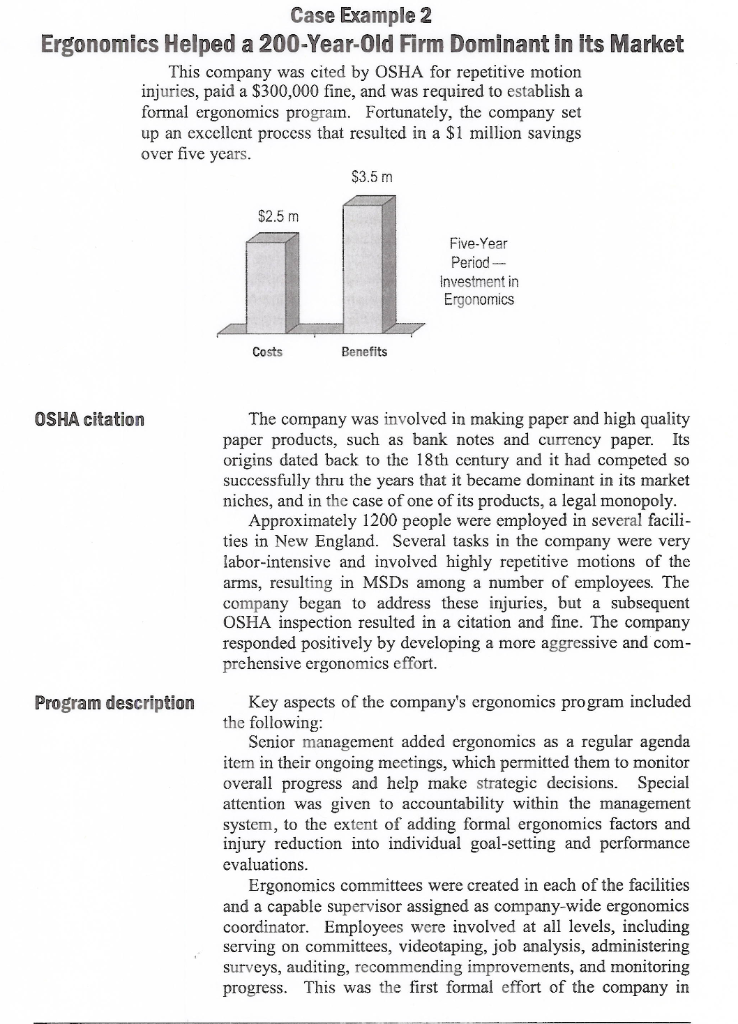

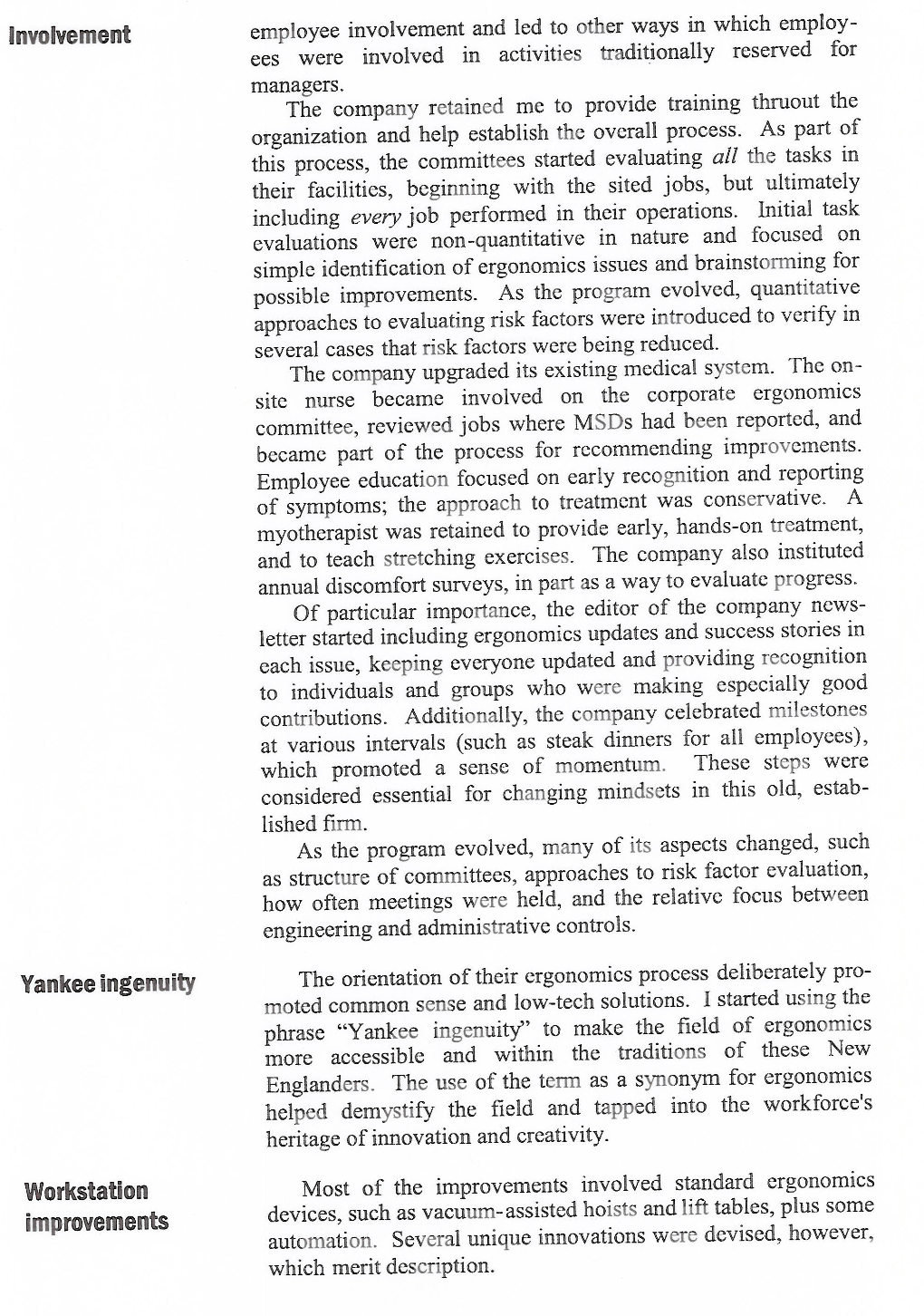

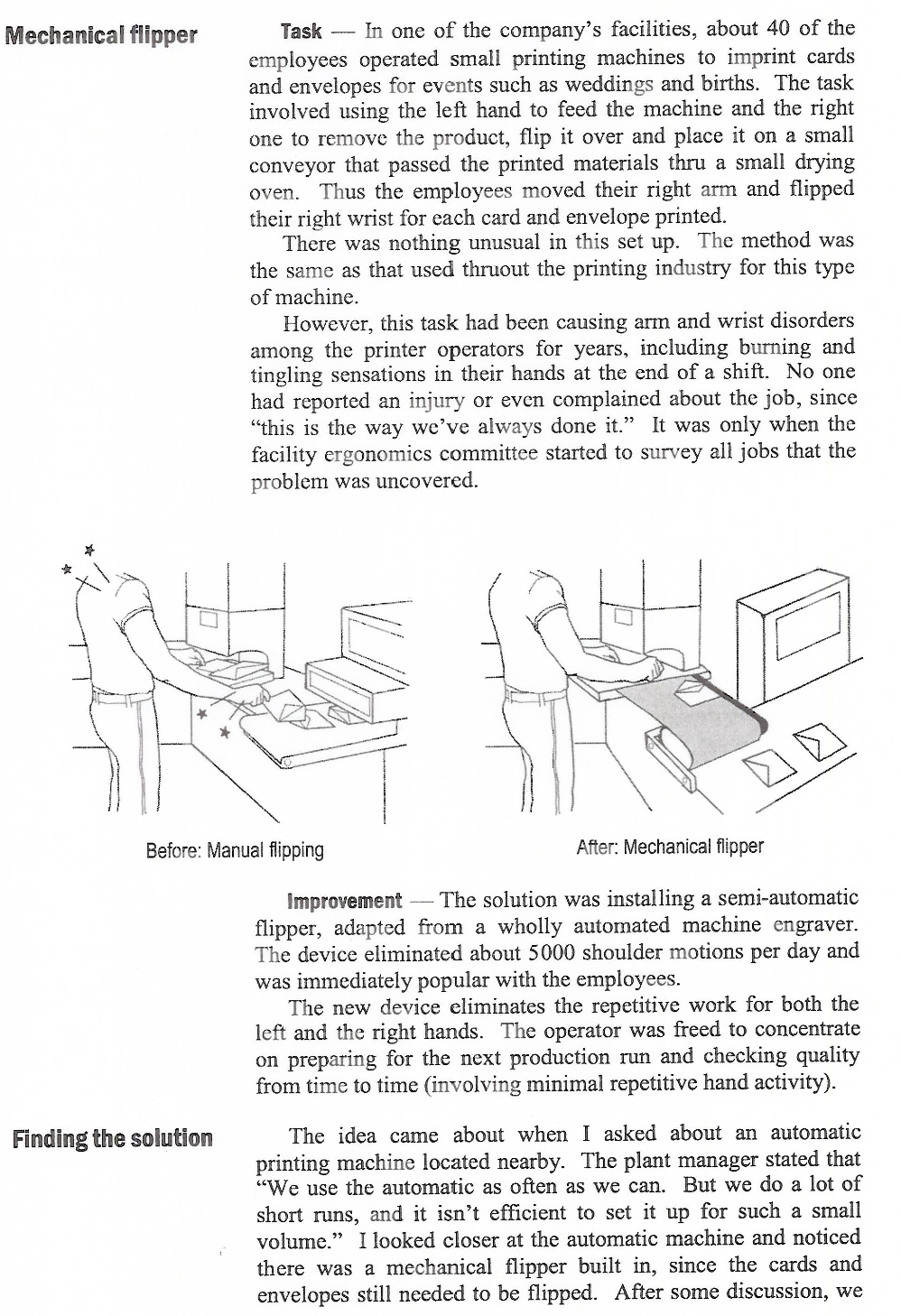

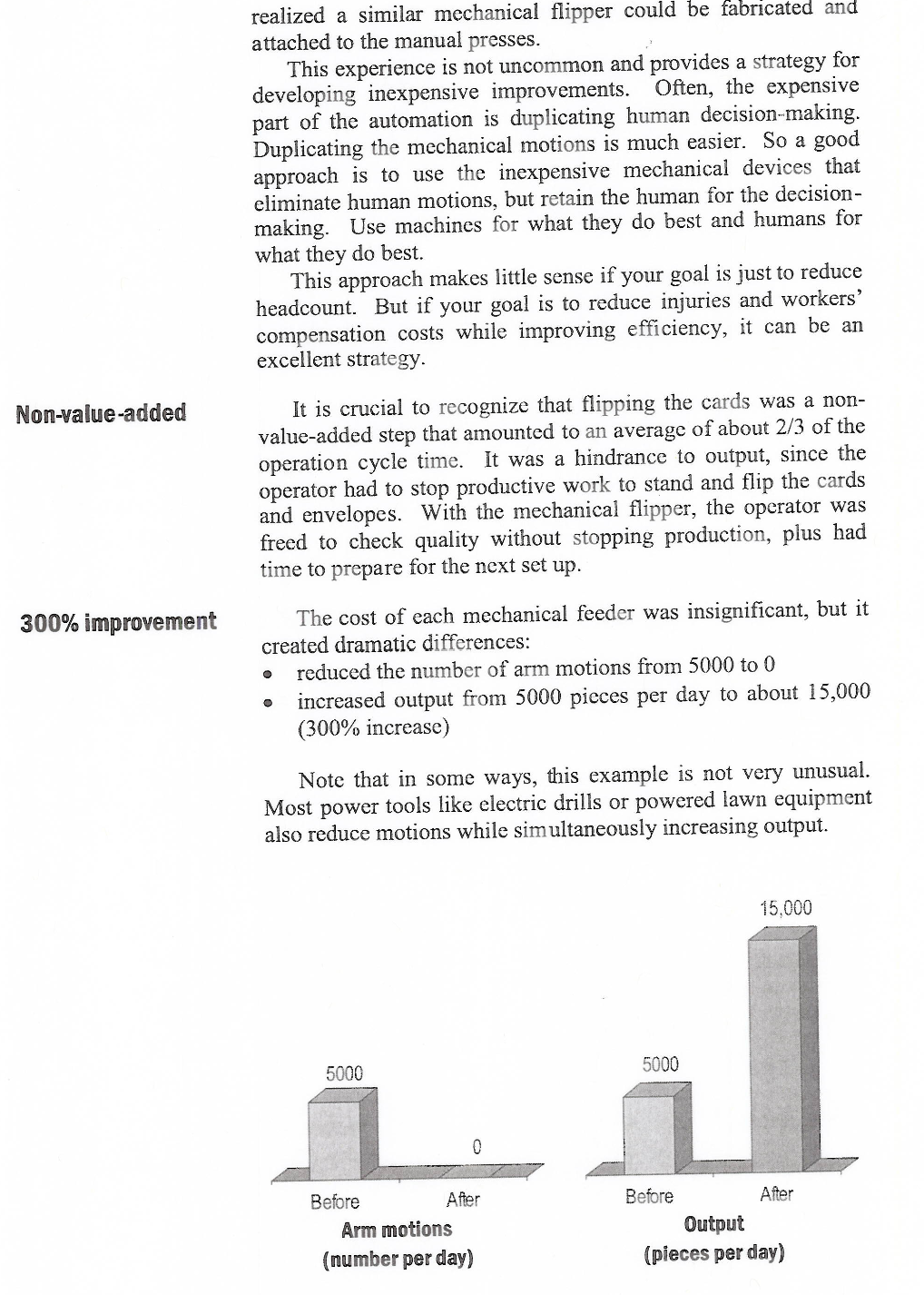

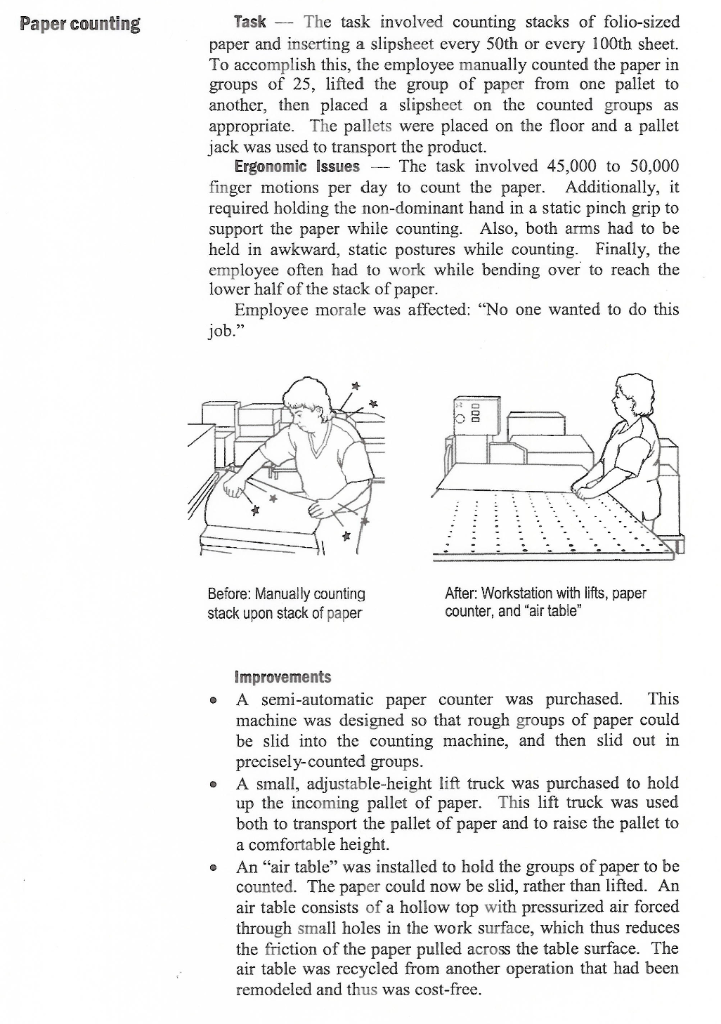

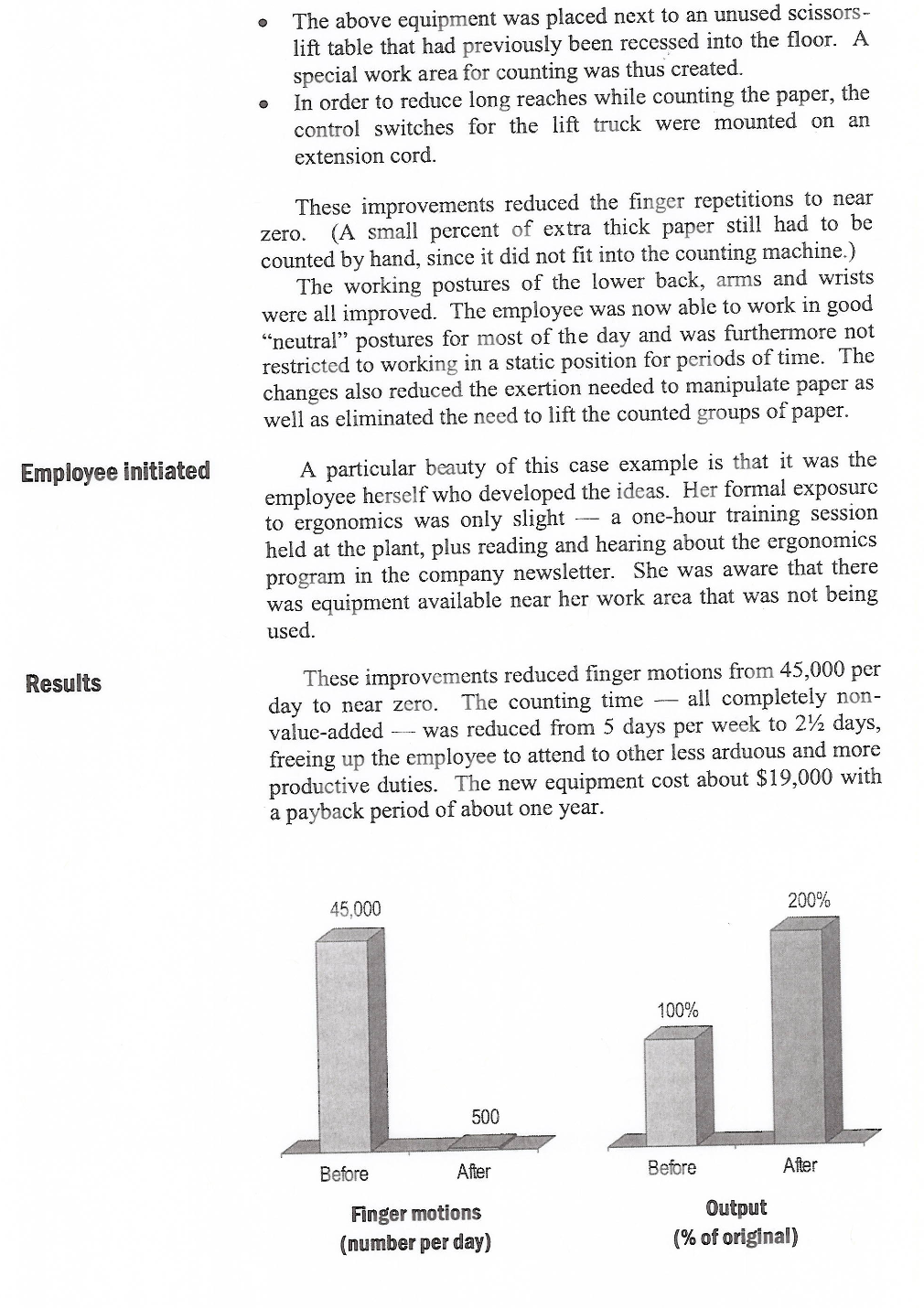

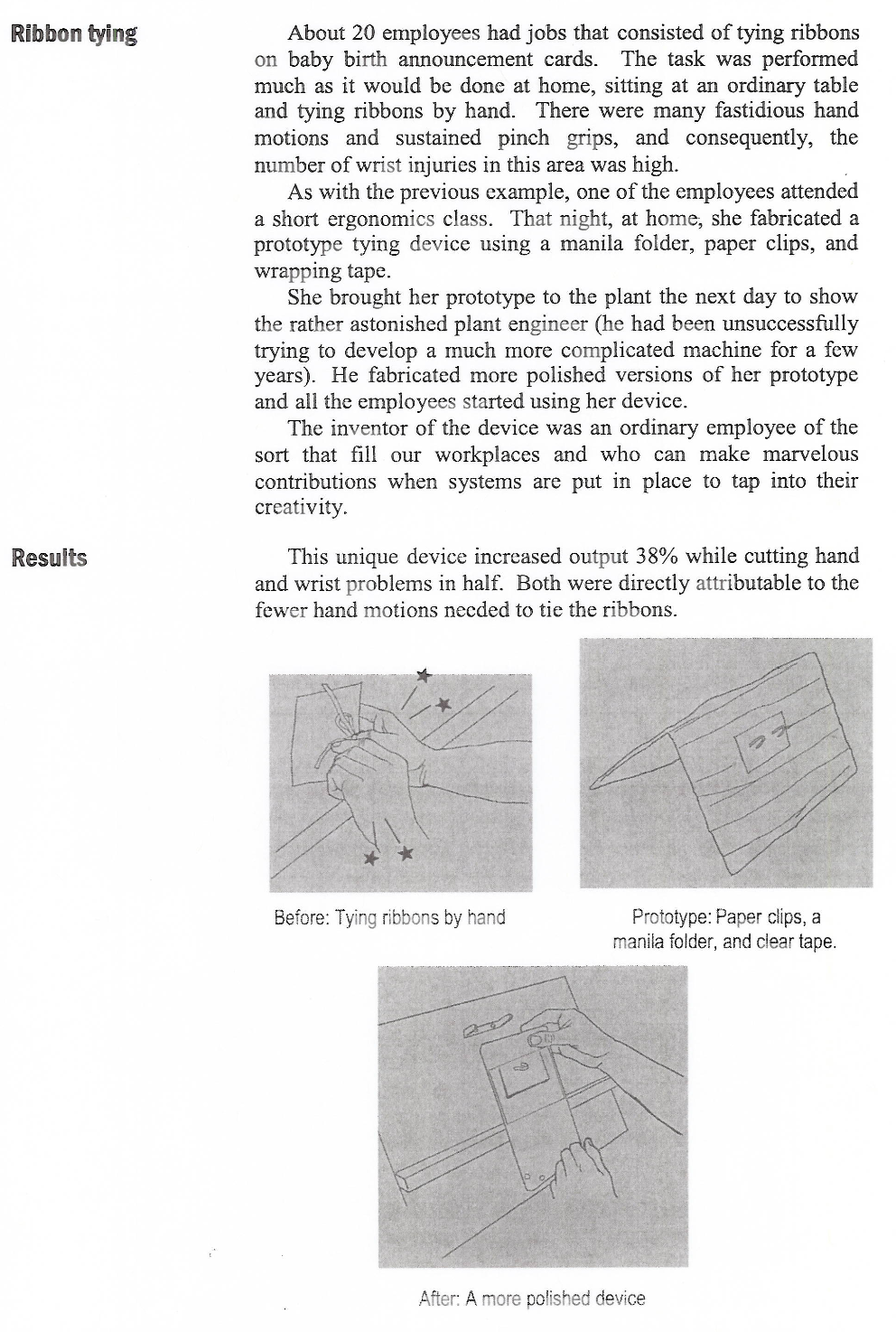

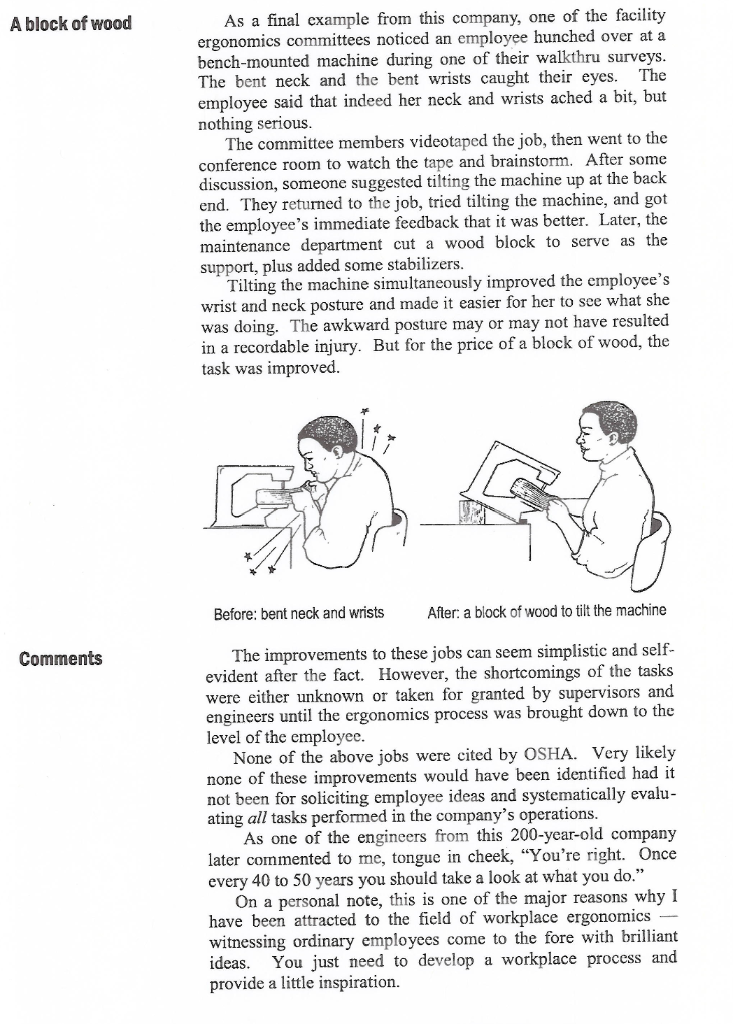

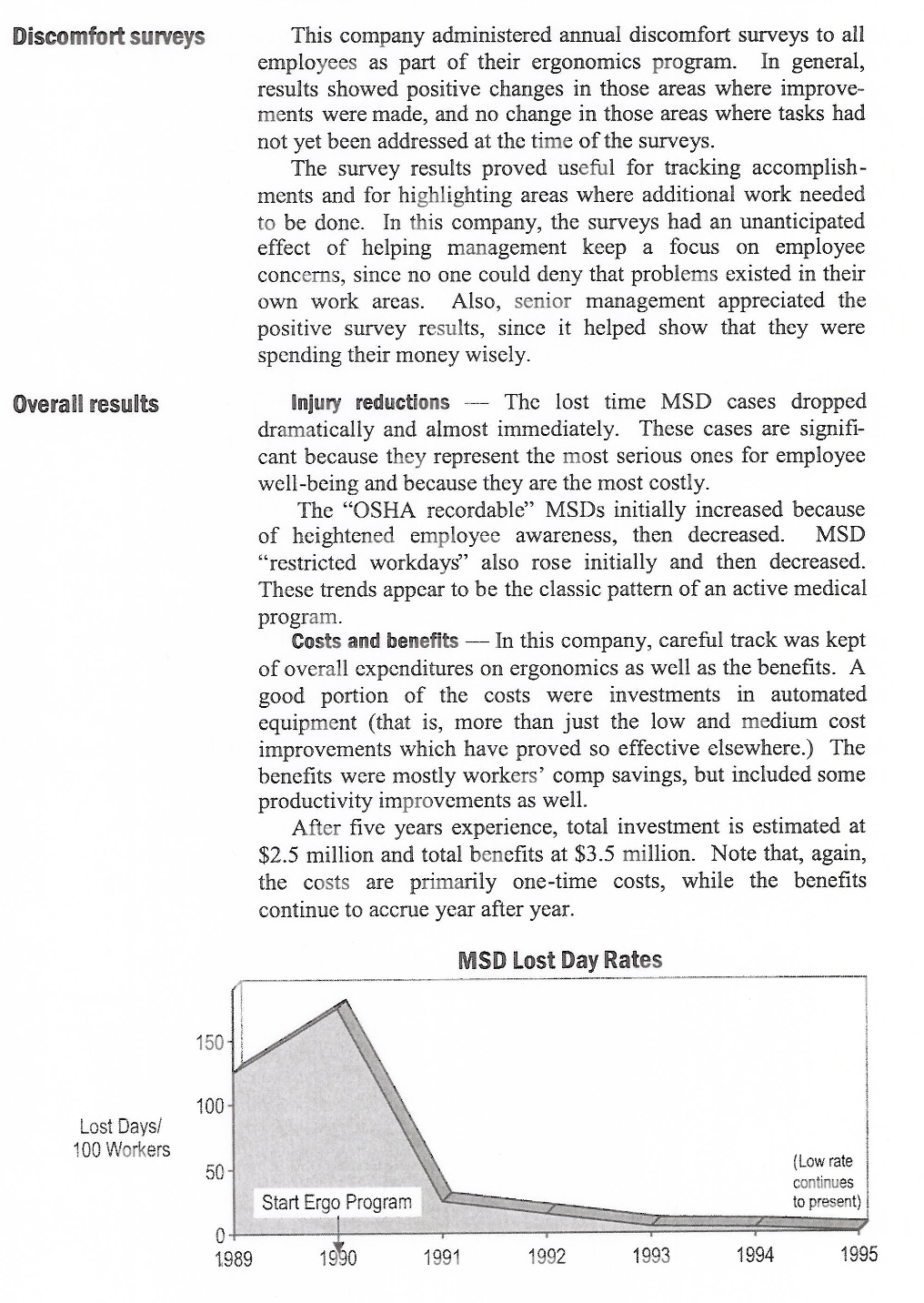

Case Example 2 Ergonomics Helped a 200-Year-Old Firm Dominant in its Market This company was cited by OSHA for repetitive motion injuries, paid a $300,000 fine, and was required to establish a formal ergonomics program. Fortunately, the company set up an excellent process that resulted in a $1 million savings over five years. OSHA citation Program description $3.5 m $2.5 m il Costs Benefits Five-Year Period --- Investment in Ergonomics The company was involved in making paper and high quality paper products, such as bank notes and currency paper. Its origins dated back to the 18th century and it had competed so successfully thru the years that it became dominant in its market niches, and in the case of one of its products, a legal monopoly. Approximately 1200 people were employed in several facili- ties in New England. Several tasks in the company were very labor-intensive and involved highly repetitive motions of the arms, resulting in MSDS among a number of employees. The company began to address these injuries, but a subsequent OSHA inspection resulted in a citation and fine. The company responded positively by developing a more aggressive and com- prehensive ergonomics effort. Key aspects of the company's ergonomics program included the following: Senior management added ergonomics as a regular agenda item in their ongoing meetings, which permitted them to monitor overall progress and help make strategic decisions. Special attention was given to accountability within the management system, to the extent of adding formal ergonomics factors and injury reduction into individual goal-setting and performance evaluations. Ergonomics committees were created in each of the facilities and a capable supervisor assigned as company-wide ergonomics coordinator. Employees were involved at all levels, including serving on committees, videotaping, job analysis, administering surveys, auditing, recommending improvements, and monitoring progress. This was the first formal effort of the company in Involvement Yankee ingenuity Workstation improvements employee involvement and led to other ways in which employ- ees were involved in activities traditionally reserved for managers. The company retained me to provide training thruout the organization and help establish the overall process. As part of this process, the committees started evaluating all the tasks in their facilities, beginning with the sited jobs, but ultimately including every job performed in their operations. Initial task evaluations were non-quantitative in nature and focused on simple identification of ergonomics issues and brainstorming for possible improvements. As the program evolved, quantitative approaches to evaluating risk factors were introduced to verify in several cases that risk factors were being reduced. The company upgraded its existing medical system. The on- site nurse became involved on the corporate ergonomics committee, reviewed jobs where MSDs had been reported, and became part of the process for recommending improvements. Employee education focused on early recognition and reporting of symptoms; the approach to treatment was conservative. A myotherapist was retained to provide early, hands-on treatment, and to teach stretching exercises. The company also instituted annual discomfort surveys, in part as a way to evaluate progress. Of particular importance, the editor of the company news- letter started including ergonomics updates and success stories in each issue, keeping everyone updated and providing recognition to individuals and groups who were making especially good contributions. Additionally, the company celebrated milestones at various intervals (such as steak dinners for all employees), These steps were which promoted a sense of momentum. considered essential for changing mindsets in this old, estab- lished firm. As the program evolved, many of its aspects changed, such as structure of committees, approaches to risk factor evaluation, how often meetings were held, and the relative focus between engineering and administrative controls. The orientation of their ergonomics process deliberately pro- moted common sense and low-tech solutions. I started using the phrase "Yankee ingenuity" to make the field of ergonomics more accessible and within the traditions of these New Englanders. The use of the term as a synonym for ergonomics helped demystify the field and tapped into the workforce's heritage of innovation and creativity. Most of the improvements involved standard ergonomics devices, such as vacuum-assisted hoists and lift tables, plus some automation. Several unique innovations were devised, however, which merit description. Mechanical flipper Task In one of the company's facilities, about 40 of the employees operated small printing machines to imprint cards and envelopes for events such as weddings and births. The task involved using the left hand to feed the machine and the right one to remove the product, flip it over and place it on a small conveyor that passed the printed materials thru a small drying oven. Thus the employees moved their right arm and flipped their right wrist for each card and envelope printed. There was nothing unusual in this set up. The method was the same as that used thruout the printing industry for this type of machine. Finding the solution However, this task had been causing arm and wrist disorders among the printer operators for years, including burning and tingling sensations in their hands at the end of a shift. No one had reported an injury or even complained about the job, since "this is the way we've always done it." It was only when the facility ergonomics committee started to survey all jobs that the problem was uncovered. Before: Manual flipping After: Mechanical flipper Improvement The solution was installing a semi-automatic flipper, adapted from a wholly automated machine engraver. The device eliminated about 5000 shoulder motions per day and was immediately popular with the employees. The new device eliminates the repetitive work for both the left and the right hands. The operator was freed to concentrate on preparing for the next production run and checking quality from time to time (involving minimal repetitive hand activity). The idea came about when I asked about an automatic printing achine located nearby. The plant manager stated that "We use the automatic as often as we can. But we do a lot of short runs, and it isn't efficient to set it up for such a small volume." I looked closer at the automatic machine and noticed there was a mechanical flipper built in, since the cards and envelopes still needed to be flipped. After some discussion, we Non-value-added 300% improvement realized a similar mechanical flipper could be fabricated and attached to the manual presses. This experience is not uncommon and provides a strategy for developing inexpensive improvements. Often, the expensive part of the automation is duplicating human decision-making. Duplicating the mechanical motions is much easier. So a good approach is to use the inexpensive mechanical devices that eliminate human motions, but retain the human for the decision- making. Use machines for what they do best and humans for what they do best. This approach makes little sense if your goal is just to reduce headcount. But if your goal is to reduce injuries and workers' compensation costs while improving efficiency, it can be an excellent strategy. It is crucial to recognize that flipping the cards was a non- value-added step that amounted to an average of about 2/3 of the operation cycle time. It was a hindrance to output, since the operator had to stop productive work to stand and flip the cards and envelopes. With the mechanical flipper, the operator was freed to check quality without stopping production, plus had time to prepare for the next set up. The cost of each mechanical feeder was insignificant, but it created dramatic differences: O reduced the number of arm motions from 5000 to 0 increased output from 5000 pieces per day to about 15,000 (300% increase) O Note that in some ways, this example is not very unusual. Most power tools like electric drills or powered lawn equipment also reduce motions while simultaneously increasing output. 5000 Before 0 After Arm motions (number per day) 5000 Before 15,000 After Output (pieces per day) Paper counting Task The task involved counting stacks of folio-sized paper and inserting a slipsheet every 50th or every 100th sheet. To accomplish this, the employee manually counted the paper in groups of 25, lifted the group of paper from one pallet to another, then placed a slipsheet on the counted groups as appropriate. The pallets were placed on the floor and a pallet jack was used to transport the product. Ergonomic Issues The task involved 45,000 to 50,000 finger motions per day to count the paper. Additionally, it required holding the non-dominant hand in a static pinch grip to support the paper while counting. Also, both arms had to be held in awkward, static postures while counting. Finally, the employee often had to work while bending over to reach the lower half of the stack of paper. Employee morale was affected: "No one wanted to do this job." Before: Manually counting stack upon stack of paper After: Workstation with lifts, paper counter, and "air table" Improvements A semi-automatic paper counter was purchased. This machine was designed so that rough groups of paper could be slid into the counting machine, and then slid out in precisely-counted groups. A small, adjustable-height lift truck was purchased to hold up the incoming pallet of paper. This lift truck was used both to transport the pallet of paper and to raise the pallet to a comfortable height. An "air table" was installed to hold the groups of paper to be counted. The paper could now be slid, rather than lifted. An air table consists of a hollow top with pressurized air forced through small holes in the work surface, which thus reduces the friction of the paper pulled across the table surface. The air table was recycled from another operation that had been remodeled and thus was cost-free. Employee initiated Results The above equipment was placed next to an unused scissors- lift table that had previously been recessed into the floor. A special work area for counting was thus created. In order to reduce long reaches while counting the paper, the control switches for the lift truck were mounted on an extension cord. These improvements reduced the finger repetitions to near zero. (A small percent of extra thick paper still had to be counted by hand, since it did not fit into the counting machine.) The working postures of the lower back, arms and wrists were all improved. The employee was now able to work in good "neutral" postures for most of the day and was furthermore not restricted to working in a static position for periods of time. The changes also reduced the exertion needed to manipulate paper as well as eliminated the need to lift the counted groups of paper. A particular beauty of this case example is that it was the employee herself who developed the ideas. Her formal exposure to ergonomics was only slight - a one-hour training session held at the plant, plus reading and hearing about the ergonomics program in the company newsletter. She was aware that there was equipment available near her work area that was not being used. These improvements reduced finger motions from 45,000 per day to near zero. The counting time all completely non- value-added - was reduced from 5 days per week to 2 days, freeing up the employee to attend to other less arduous and more productive duties. The new equipment cost about $19,000 with a payback period of about one year. 45,000 500 Before After Finger motions (number per day) 100% Before 200% After Output (% of original) Ribbon tying Results About 20 employees had jobs that consisted of tying ribbons on baby birth announcement cards. The task was performed much as it would be done at home, sitting at an ordinary table and tying ribbons by hand. There were many fastidious hand motions and sustained pinch grips, and consequently, the number of wrist injuries in this area was high. As with the previous example, one of the employees attended a short ergonomics class. That night, at home, she fabricated a prototype tying device using a manila folder, paper clips, and wrapping tape. She brought her prototype to the plant the next day to show the rather astonished plant engineer (he had been unsuccessfully trying to develop a much more complicated machine for a few years). He fabricated more polished versions of her prototype and all the employees started using her device. The inventor of the device was an ordinary employee of the sort that fill our workplaces and who can make marvelous contributions when systems are put in place to tap into their creativity. This unique device increased output 38% while cutting hand and wrist problems in half. Both were directly attributable to the fewer hand motions needed to tie the ribbons. Before: Tying ribbons by hand OD Prototype: Paper clips, a manila folder, and clear tape. After: A more polished device A block of wood Comments As a final example from this company, one of the facility ergonomics committees noticed an employee hunched over at a bench-mounted machine during one of their walkthru surveys. The bent neck and the bent wrists caught their eyes. The employee said that indeed her neck and wrists ached a bit, but nothing serious. The committee members videotaped the job, then went to the conference room to watch the tape and brainstorm. After some discussion, someone suggested tilting the machine up at the back end. They returned to the job, tried tilting the machine, and got the employee's immediate feedback that it was better. Later, the maintenance department cut a wood block to serve as the support, plus added some stabilizers. Tilting the machine simultaneously improved the employee's wrist and neck posture and made it easier for her to see what she was doing. The awkward posture may or may not have resulted in a recordable injury. But for the price of a block of wood, the task was improved. Before: bent neck and wrists After: a block of wood to tilt the machine The improvements to these jobs can seem simplistic and self- evident after the fact. However, the shortcomings of the tasks were either unknown or taken for granted by supervisors and engineers until the ergonomics process was brought down to the level of the employee. None of the above jobs were cited by OSHA. Very likely none of these improvements would have been identified had it not been for soliciting employee ideas and systematically evalu- ating all tasks performed in the company's operations. As one of the engineers from this 200-year-old company later commented to me, tongue in cheek, "You're right. Once every 40 to 50 years you should take a look at what you do." On a personal note, this is one of the major reasons why I have been attracted to the field of workplace ergonomics witnessing ordinary employees come to the fore with brilliant ideas. You just need to develop a workplace process and provide a little inspiration. Discomfort surveys Overall results Lost Days/ 100 Workers 150- 100- 50- 0- 1989 This company administered annual discomfort surveys to all employees as part of their ergonomics program. In general, results showed positive changes in those areas where improve- ments were made, and no change in those areas where tasks had not yet been addressed at the time of the surveys. The survey results proved useful for tracking accomplish- ments and for highlighting areas where additional work needed to be done. In this company, the surveys had an unanticipated effect of helping management keep a focus on employee concerns, since no one could deny that problems existed in their own work areas. Also, senior management appreciated the positive survey results, since it helped show that they were spending their money wisely. Injury reductions The lost time MSD cases dropped dramatically and almost immediately. These cases are signifi- cant because they represent the most serious ones for employee well-being and because they are the most costly. The "OSHA recordable" MSDs initially increased because of heightened employee awareness, then decreased. MSD "restricted workdays" also rose initially and then decreased. These trends appear to be the classic pattern of an active medical program. Costs and benefits - In this company, careful track was kept of overall expenditures on ergonomics as well as the benefits. A good portion of the costs were investments in automated equipment (that is, more than just the low and medium cost improvements which have proved so effective elsewhere.) The benefits were mostly workers' comp savings, but included some productivity improvements as well. After five years experience, total investment is estimated at $2.5 million and total benefits at $3.5 million. Note that, again, the costs are primarily one-time costs, while the benefits continue to accrue year after year. MSD Lost Day Rates Start Ergo Program 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 (Low rate continues to present) 1995