Question: Requirements for submission of Class Assignments The assignment needs to be typed, in the following format: Font size 12 point, spacing 1.5, left and right

Requirements for submission of Class Assignments The assignment needs to be typed, in the following format: Font size 12 point, spacing 1.5, left and right margins set at 2.5. The pages need to be numerated. In the content list page, numbers are to be given under the different sub-headlines. The number of pages of the paper does not include front page, content list, bibliography and appendix/s.

Headlines are to be written from the left margin, not centred. If the headlines are ranged in sub headlines, there should not be more than three levels. The ranking is to be shown by using capital and lower case letters and the decimal number system as in the following example: 3. THEORIES OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS 3.1. Conditioned theoretical explanations 3.1.1. Classical theory

References needs to be given in parenthesis in the text (and not in footnotes). A proper reference is given with the name of the author, publication year and page number/s when necessary (page number/s of the reference is used when giving direct quote/s). (Hirst 1987) (Myhre 1988:160-162) (Handal & Lauvs 1983:59) (Atkinson et.al. 1987:223) (Sommerschild 1985) If the reference has two authors, both names need to be written. If the reference has more than two authors, write the name of the author first mentioned followed by et.al., as shown in the example above. The references used in the text must in addition always be cited in the bibliography. The bibliography needs to be given in alphabetical order at the end of the assignment. Example of a bibliography: Book written by author: Surname, First name (year): Full title of the book. Place where published: Publisher. (Edition, nr) Cummings, William K. (2003): The Institutions of Education, Oxford: Symposium Books.

The front page of the assignment must contain following information in given order: Title of the paper/assignment What kind of assignment it is, e.g. MGT 380 Your name The given semester and year Comsats University Faculty of Management sciences Department of Management sciences Referencing:

Material required for each assignment Justification of the problem Research question at least 7 Research objectives at least 4 Literature review 500 words Model discussion 200 words Analysis 100 words Referencing NOTE: There are several ways to do referencing in the text. It can be done directly into the text: In this line of arguments I refer to Reidar Myhre (1990) who claims that .. Reidar Myhre (1990) claims that etc. Year and alternatively page number/s (when giving direct quote/s) need to be given, either following the author's name or after the given argument. The reference can also be given in parenthesis after the argument/idea/concept of the author is presented, e.g. (Myhre 1990). If you wish to show that several authors/researches support the same argument/idea/concept, it can be listed as followed (Eidheim 1971, Hoem 1978, Hgmo 1989).

KINDLY MAKE IT AS REQUIREMENTS! JUST SEND ME IN TYPED FORM I WILL ARRANGE IT BY MYSELF ON MICROSOFT WORD! JUST NEED IN TYPED FORM! KINDLY MADE IT AS EARLY AS POSSIBLE

IF U FIND SOMETHING IN COMPLETE THEN KINDLY ASSUME IT BY YOURSELF AND MAKE IT COMPLETE!

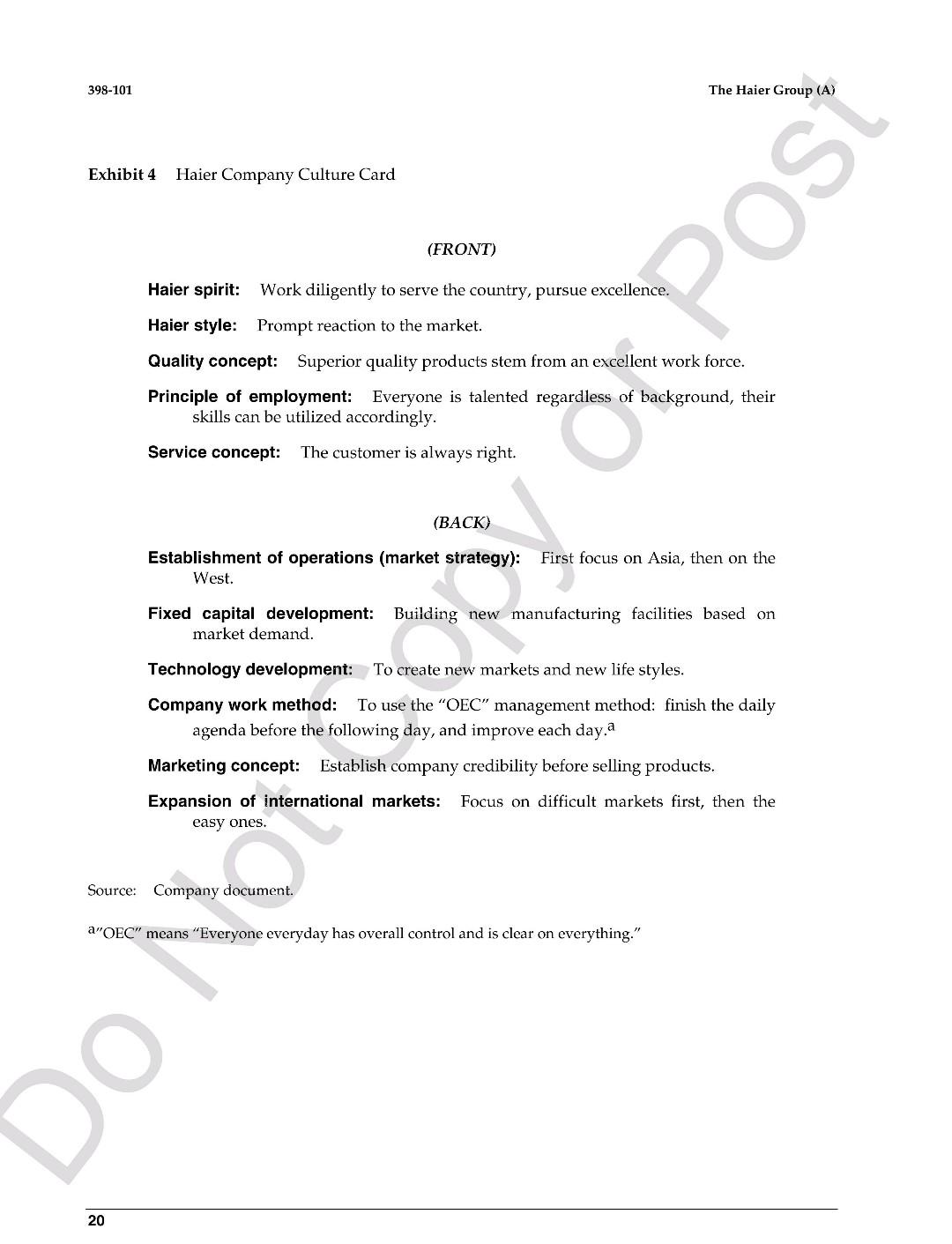

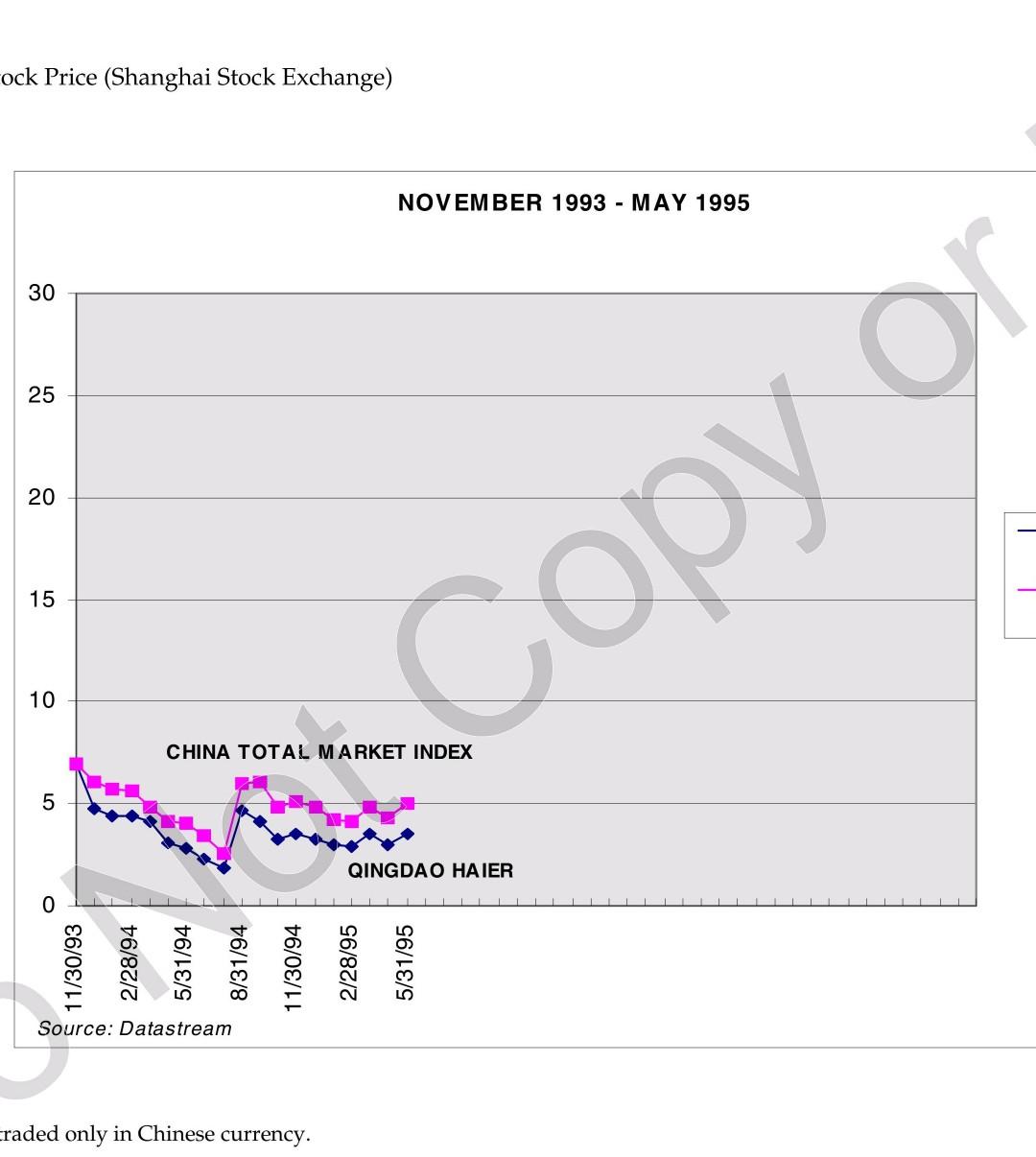

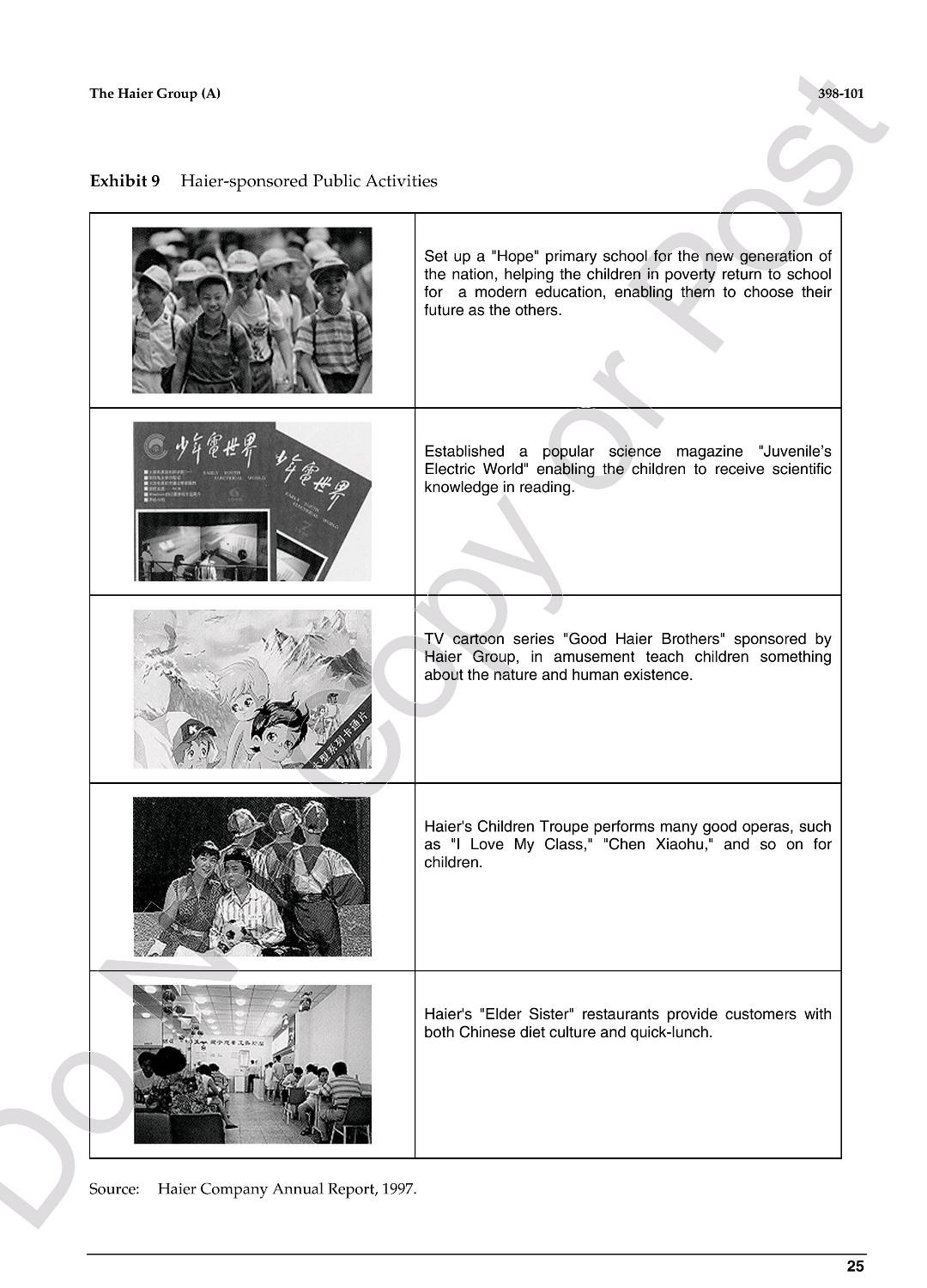

398-101 The Haier Group (A) Exhibit 4 Haier Company Culture Card Post (FRONT) Haier spirit: Work diligently to serve the country, pursue excellence. Haier style: Prompt reaction to the market. Quality concept: Superior quality products stem from an excellent work force. Principle of employment: Everyone is talented regardless of background, their skills can be utilized accordingly. Service concept: The customer is always right. (BACK) Establishment of operations (market strategy): West. First focus on Asia, then on the Fixed capital development: Building new manufacturing facilities based on market demand. Technology development: To create new markets and new life styles. Company work method: To use the "OEC" management method: finish the daily agenda before the following day, and improve each day.a Marketing concept: Establish company credibility before selling products. Expansion of international markets: Focus on difficult markets first, then the easy ones. Source: Company document. a"OEC" means "Everyone everyday has overall control and is clear on everything." SON 20 The Haier Group (A) 398-101 ASA Exhibit 5 Excerpt from Company Newsletter: Example of Zhang Ruimin's Calligraphy *-. , All E414 Andy,M 4, and be A.22,p. AF ,A1A361- man , et AAAA 2W Wyntal he Lindqzrast It is very inspiring that the words of the heart should go with love. We have learned from Liu Xiangyang, who gained his success through hard work and not resting on his laurels. From him, we have also learned what Haier's Spirit is. Facing new situations and unknown people in a remote area, Liu was never unfriendly, never complained, and never made excuses. He was self-disciplined and made the best out of the conditions he faced in order to achieve his objectives. His behavior was a shining example of the Haier spirit, as we expect to see. We need always to maintain this Spirit. With it, we will not fail. -Zhang Ruimin Source: Haier News. 21 Exhibit 6 Workplace Slogans Haier Spirit: Work Diligently to Serve the Country, Pursue Excellence. Haier Style: Prompt Reaction to the Market. C Specialization, Zero Defect. Daler MASTER Source: Produced by casewriter. cock Price (Shanghai Stock Exchange) NOVEMBER 1993 - MAY 1995 30 25 20 15 10 Copy of CHINA TOTAL MARKET INDEX 5 QINGDAO HAIER O 8/31/94 11/30/94 2/28/95 Source: Datastream Fraded only in Chinese currency. The Haier Group (A) Is Exhibit 9 Haier-sponsored Public Activities Set up a "Hope" primary school for the new generation of the nation, helping the children in poverty return to school for a modern education, enabling them to choose their future as the others. @ 448 #f ENE Established a popular science magazine "Juvenile's Electric World" enabling the children to receive scientific knowledge in reading. HANS TV cartoon series "Good Haier Brothers" sponsored by Haier Group, in amusement teach children something about the nature and human existence. , Haier's Children Troupe performs many good operas, such as "I Love My Class," "Chen Xiaohu," and so on for children. Haier's "Elder Sister" restaurants provide customers with both Chinese diet culture and quick-lunch. 0 Source: Haier Company Annual Report, 1997. 25 398-101 The Haier Group (A) empty in anticipation of future growth. (By 1997, all the empty area would be covered by new projects.) Following the slowdown after the Tiananmen Square incident in 1989, consumer demand in China had revived and its growth showed no signs of slackening. $ Zhang, a charismatic man and at six feet unusually tall for a Chinese, had become something of a business celebrity in China. In the coming decade, he hoped to establish Haier as a brand name as well known worldwide as Matsushita or General Electric, and was determined to enter the Fortune 500. In 1995, Haier also began to set up a refrigerator and air conditioner plant in Indonesia. This foreign factory represented the final leg of Zhang's one-third-by-three strategy, according to which Haier would divide its business equally between sales in the domestic market, exports, and foreign sales generated by overseas manufacturing facilities. The Haier Group's success to date was due, Zhang believed, to the "Haier enterprise culture," which encouraged (and enforced) personal accountability, while combining high quality, quick service, and meticulous attention to customer preferences. In Zhang's opinion, the most important factor of production was human capital, and the role of management was to develop it. Zhang strove to emphasize innovation ("take different approaches to traditional and exceptional problems") and to learn through partnerships with international firms, such as Liebherr of Germany, Matsushita of Japan, and Merloni of Italy. In China, Zhang sought to grow Haier primarily through the acquisition of poorly managed companies with good products in promising markets. Haier would transform the acquired companies by instilling its enterprise culture and using its self-described McDonald's method" of imbuing a wide array of separate facilities with uniformly high quality. Haier was in the vanguard of an officially sanctioned trend toward company mergers and industry consolidation as China sought to restructure its economy. So far the strategy had been successful, but Zhang was still debating whether it would work at Red Star. About one-third the size of the Haier Group, Red Star would dwarf the company's previous acquisitions. (See Exhibit 1 for sales, income, profit, products; see Exhibit 2 for RMB-U.S. dollar exchange rate.) Haier's Beginnings In early 1984, while walking near his office in the Household Appliance Division (HAD) of the municipal government, Zhang Ruimin noticed lines of people waiting outside a run-down plant, the Qingdao General Refrigerator Factory. As vice general manager of HAD, Zhang helped to oversee the plant. Why were the people waiting there, he wondered. Many of them had come in from the countryside, which was flush with cash from crop sales under the reforms of Deng Xiaoping. They wanted refrigerators so badly, he soon realized, that they were prepared to buy them as soon as they came off the assembly line, unwilling even to wait for local stores to stock them. Prior to Deng's reforms, which encouraged factories to increase production of household appliances, they were rarely available and difficult to buy, often requiring "connections" with influential clerks or bosses.1 In 1981, for example, there were only two refrigerators per 1,000 city households.2 Zhang was witnessing, he believed, the birth of a new consumer market. What Zhang saw got him thinking. A refrigerator could save homemakers up to two hours per day, which they were accustomed to spending in search of fresh food. Yet despite this demand, the 1 Fox Butterfield, China: Alive in the Bitter Sea (Bantam Books, 1982), p. 108. 2 "China Survey," The Economist, November 28, 1992, p. 4. 2 The Haier Group (A) 398-101 C. Qingdao factory hovered on the verge bankruptcy. No effective leadership had emerged within the company. Because components were frequently missing, he knew, the factory rarely ran at capacity, and often shut down completely. Many of the refrigerators that came off the assembly line were ugly and scratched, with doors that wouldn't close properly. Moreover, the company offered virtually no on-site repair service. Because the factory often ran out of spare parts, returning a defective refrigerator was no guarantee it could be replaced or fixed. Even worse, new Chinese manufacturers were beginning to offer similarly inexpensive refrigerators, a competition that was sinking Qingdao General Refrigerator. Nonetheless, when refrigerators became available, consumers instantly lined up for them. Zhang decided, almost immediately, that this tiny factory represented a way to prove himself. Though he had a steady job-as the vice general manager of HAD, responsible for control and approval of technology for new productshe found his administrative duties boring and too easy. Zhang chafed under the old command style system of the Household Appliance Division; being told what to do from above, he had virtually no opportunity to try out his ideas. And he had lots of ideas. I wanted to take just one factory, and make it the best. I wanted to train people in quality assurance and production. Then I wanted to expand, with young people who were willing to learn and adapt." Zhang's Background Zhang's parents were workers without influence or connections in Qingdao. From an early age, they encouraged their son's desire to change things, to make a difference in society. "They taught me that my beliefs can be realized," he said. Like many Chinese families, they emphasized education as a means of advancement; his given name, Ruimin, meant "sensitive and intelligent." Zhang excelled in ancient literature and philosophy, learning to read the Chinese classics of Confucius and Laozi in their original form. He was becoming, in the time-honored mold, a poet and philosopher with an appetite for practical accomplishment. Upon graduation from Qingdao high school in 1968, his world abruptly changed. The Cultural Revolution, a national campaign to sweep away "old thinking," had closed down most schools and universities. Scouring the countryside and entering private homes, Mao Zedong's Red Guards smashed countless irreplaceable antiques and destroyed historical sites. Entrepreneurs, shop owners, and millions of innocent people were denounced as capitalist roaders, many of them forced to kneel in broken glass or beaten to death in front of their families. With the exception of the Red Book, a collection of Mao's writings, most older books were confiscated or burned. All of Zhang's academic achievementshis elegant and much admired calligraphy, the memorization of ancient texts, his poetry--were suddenly viewed as "feudal" remnants that hindered China from a glorious future. As a result, Zhang was forced to enter a metal processing plant, giving up his dream of higher education and scholarship for the next 20 years. He never left Qingdao. The plant he entered was run in the Soviet style, as a tiny cog in the centrally planned economy. No individual initiative could be taken, and no deviations from the yearly plan would be entertained by top management. In fact, aside from a few "rush periods" to meet its monthly quotas, the factory rarely functioned at capacity. As the Cultural Revolution degenerated into a chaotic civil war between Red Guard factions, many of the qualified personnel were removed or demoted, further crippling the factory. Zhang, who was a highly energetic and ambitious youth, sank into years of frustration and forced idleness. Like many of his generation, it only heightened his passion to excel; See Jung Chang, Wild Swans (Anchor Books, 1991). 3 The Haier Group (A) 398-101 For Zhang, Deng's policies opened a new world as well. As books and ideas began to flow into China, he devoured the literature on American and Japanese management. He found many parallels to Chinese philosophy. The advice of Harvard Business School Professor Michael Porter, in his Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors,5 melded neatly with the battlefield wisdom of Sun Tzu: product differentiation, with constant sensitivity to customer needs, was one way to achieve success in the market. It was strikingly similar to Lee laocca's marketing advice: when aiming the gun, Zhang said, you have to follow the target. Zhang was particularly impressed with the Total Quality Management system of General Electric, under the direction of CEO Jack Welch. As Zhang explained, GE's enterprise culture emphasized the personal responsibility of employees for continual innovation. In one unit, Zhang recalled, two quality engineers led the effort to improve GE products; they monitored their production line so well that they didn't need inspectors. By leading themselves, funneling their energies in the company," Zhang explained, "they were realizing their identities. I wanted to do the same in my company." Zhang also wanted a sense of common purpose to discipline employee initiative and action; he concluded that a culture center would be the organizational instrument to unite individual efforts into a coherent strategy. Zhang also studied The Fifth Discipline: the Art and Practice of the Learning Organization, by MIT Professor Peter Senge, particularly Senge's diagram of a cohesive organization, with individuals working in a consistent overall direction like the coherent light in a laser beam or a jazz ensemble performing "in the groove"?as in the Confucian way, rather than as a disparate collection of individuals in conflict. D Qingdao Refrigerator Once Zhang made up his mind to take over the Qingdao General Refrigerator Factory in 1984, he began to plot a long-term strategy. Following the example of the Japanese giant Matsushita, Zhang aspired to become nothing short of the number one refrigerator manufacturer in China. He would accomplish this, he promised, within 10 years. Then," he said, just as Matsushita had done, I will move on to other products." Because Qingdao General Refrigerator appeared in dire straitsit was operating with an annual deficit of 1.47 million RMB and with a debt of US$168,000it was not difficult to convince his colleagues in the municipal government to appoint him president. If he did poorly, they could always fire him. The first thing he needed to do was build a team, but few appeared willing to risk losing secure jobs for the uncertain future of managing a failing refrigerator plant. Nonetheless, in the wake of the Cultural Revolution, Zhang understood that many people of his generation longed for a productive work environment and were prepared to completely dedicate themselves to the right cause. One of his most capable colleagues in the Household Appliance Division, Mrs. Yang Mianmian, was immediately interested. I told her I believed in her, and that was what she needed most then," Zhang explained. An engineer and later a government official reporting to Zhang, Mrs. Yang brought formidable managerial skills to the new organization. At the same time, she was unstintingly cheerful and even impish at times. Though her given name, Mianmian, meant "soft like a lamb," one of her colleagues said: "She ruled with a steel fist." She would be key to his efforts to grow into a large conglomerate. By coaxing two other executives from 5 The Free Press, 1980. 6 Doubleday/Currency, 1990. 7 Ibid., pp. 234-5. 5 398-101 The Haier Group (A) Co the municipal government into the company, Zhang's leadership team was in place by December 1984. Zhang turned to the values he wished to instill in the organization. Although demand for household appliances seemed certain to expand for the foreseeable future, Zhang believed that competing solely on price was a losing tactic in the longer term. Many other competitors were already offering virtually identical products, and once the expansion of the consumer economy slowed, a price war was sure to follow. With the low-quality goods then available, there would be little reason for consumers to stick with any given brand. Besides, foreign firms with far better reputations for quality than Chinese manufacturers were already eyeing the market. Zhang was convinced that Chinese customers were sophisticated enough to desire higher-quality items and reliable service, and that was how he decided to distinguish his company. The real problem, he understood, was in the minds of the workers in the Qingdao General Refrigerator Factory: "They were not used to thinking about how to do a good job or take personal responsibility and initiative. Their refrigerators came off the assembly line in terrible shape, and they had no idea what good service was." If employees felt personally responsible for maintaining quality and creating value, he thought, the market would recognize this; a system of accountability, along clearly defined lines of responsibility, would also have to be put in place. It was the kernel of what became Haier's enterprise culture. Because of the legal status of the factory-it was a "collective enterprise" whose ultimate authority was the municipal government-Zhang was not allowed to fire a large portion of the 1,200- person work force. It would create too much local unemployment. Besides, though not clearly defined, the collective enterprise "belonged" to its workers, who enjoyed certain rights to be negotiated under the watchful eye of the municipal government. Unlike state-owned enterprises, however, the government did not own, or have any claim-other than taxesto a collective enterprise's assets and profits. Assuming he could turn it around, Zhang would be able to re-invest most of the factory's profits into the company. In the meantime, however, the factory had to borrow from surrounding villages to pay for workers' salaries.8 When workers in the Qingdao General Refrigerator Factory failed to improve quickly, Zhang knew they needed a shock. Early in 1985, while inspecting the refrigerators in stock, he pulled out 76 that were flawed in some way and ordered workers to smash them. The move reverberated not just within the factory, but throughout the Chinese retail world as wellworkers couldn't believe Zhang would waste their inventory of refrigerators, some of which were only scratched, while financial losses remained enormous. That got their attention," Mr. Zhang laughed. "They finally understood I wasn't going to sell just anything, like my competitors would. It had to be the best." With that, factory workers and managers were ready to take a second look at how the company operated. With only an idea, he explained, "the workers opened their minds." Zhang strove to instill discipline by example. He routinely worked 14-hour days; to save money while the company's financial situation improved, he took public transportation to work and stayed in inexpensive hotels on business trips. To complement the uniforms of the factory workers, Zhang's managers adopted a common dress code: blue ties and pin stripe suits with leather loafers; the only variations in evidence were the color of sweaters that managers chose. At one point, while experimenting with a smoke-free workplace to enhance worker productivity, all of the company's top 8 Fons Tuinstra, "From Rags to Riches: Haier Group Asserts Its Independence," Deutsche Press Agentur, August 21, 1996. Kathy Chen, "China Refrigerator Maker Stickler for Service Quality," Asian Wall Street Journal, September 18, 1997, p. 1. 9 6 The Haier Group (A) 398-101 in order executives quit smoking. In 1988, Zhang returned part-time to his studies, a correspondence course for the Chinese equivalent of an MBA. To reinforce the attitudes he was cultivating, Zhang established an evaluation system that linked performance to wages and promotions. He sought to make the company's processes more efficient. Following "Time Operation Research," a modern version of Taylorism, Zhang and his team went over every procedure in the factory, gauging what was necessary and what wasn't. "Other companies [in China] didn't do this much research," he said. "We constantly sought to make things better in some way." A parallel inquiry analyzed the work routines of the company's managers. Time Operation Research offered a way to measure employee performance and became the vehicle for the company's "point wage system," an "objective" appraisal system indexing job complexity and difficulty-whether "heavy, light, or skilledagainst quality of work and service.10 Every month, all employees submitted themselves to this assessment. The better performers were entitled to higher wages and, eventually, more responsible positions. The assessment was also employed to evaluate employees' aptitudes for their current positions, which often resulted in job transfers. Errant or sluggish workers could be subject to heavy fines, sometimes up to half of their wages, and were forced to explain their failings to their immediate colleagues. It was Zhang's way of introducing competition into the workplace, tying ambition and personal initiative to the wage structure. But worker attitude was only the beginning. Another cornerstone of Zhang's strategy was the factory's foreign partner: Liebherr-Haushaltsgerate of West Germany was ready to inject modern refrigerator manufacturing technology into the plant. "First we observe and digest (the new methods)," Mr. Zhang explained. Then we imitate it. In the end, we understand it well enough to design it independently." The company would never, he emphasized, become dependent on regular infusions of foreign technology. The collaboration worked so well that, in 1985, the collective chose Haier as its new name, a direct translation of Liebherr, or "Dear Sir," into Chinese. The company's logoa dark- haired Chinese child with his thumb pointing upward as number one" embracing a blond European gaminealso symbolized the union. In a later collaboration, Haier licensed refrigeration technology from Mitsubishi of Japan. However, Haier engineers created the first convertible freezer compart- ment on their own. The units could serve both as cold storage in the summer and as a freezer unit in winter, when Chinese consumers sought to preserve otherwise unavailable seasonal food stuffs. Zhang rewarded his best workers with places at the newest assembly lines. Within the first year, Haier almost broke even, and in 1986 turned a profit of 1 million RMB. By 1988, with sales steadily improving, it won a gold medal for quality from the Chinese Quality Management Association, a state organization. By 1991, Zhang reached his goal: Haier became the number one refrigerator manufacturer in China, both in terms of sales at 309,000 units (830 million RMB) and recognized quality. "Now," he said, "we could let our reputation precede our new products.... ... It was time to diversify... and seek international quality assurances." With the success of Haier, Zhang's leadership was undisputed, both within the company and by officials in the municipal government. He turned his attention to consolidate what he had learned in order to expand into other product lines. Governance of Collective Enterprises As a "collective enterprise," Haier operated within a legally ambiguous system of governance. A fixture of post-1949 China, collective enterprises had been designed to allow groups of artisans and 10 See James Harding, "Rising Star in China's Infant Corporate Culture," The Financial Post, November 21, 1997, p. 69. 7 398-101 The Haier Group (A) small entrepreneurs as well as neighborhood unitsthe "danwei"to band together for purposes of commercial activity, farming, and transportation. Avoiding the capitalist overtone that "private" implied, their ownership was "collective" in the sense that together the members in theory owned all production facilities. 11 Approval to operate, merge, dissolve, divide, or make other changes had to be secured from government authorities in charge of collective enterprises as well as from local officials of the State Administration of Industry and Commerce. 12 In 1997, China had approximately 25 million collective enterprises, employing 500 million. In most collective enterprises, two poles of authority had evolved in practice: (1) the company managers who handled business strategy and the majority of day-to-day operations, and (2) the managers who handled personnel issues and monitored the company from a political point of view. The influence of the Communist Party was felt most directly through the second channel. Nonetheless, the lines of authority were almost never clearly spelled out in either the company articles of association or its ownership structure. The larger collective enterprises, according to Yang Mianmian, tended to operate as "closed information systems," unaccustomed to seek or accept information from outside sources. During China's period of Soviet-style planned economy, collective enterprises developed habits ill-suited for a market economy: among these were preferences for quantity over quality and sales forces unaccustomed to seeking new customers. The enterprises took their existence and survival for granted. Though China's bankruptcy law dated to 1986, only 2,000 firms had filed for bankruptcy nationwide by 1995.13 Neither banks nor governments were willing to force bankruptcies. Banks feared their bad loans would never be repaid, and governments feared the social and political consequences.14 As many collective enterprises expanded into much larger entities, the laws governing their management and operation evolved in a murky and ill-defined process, often according to established custom and negotiation with local politicians. Though no longer a government administrator, Zhang as Haier's chairman and CEO was still considered an appointee who served at the pleasure of the municipal government. He could in principle be fired for any reason-poor profitability, labor disputes, or mismanagement of funds. Every year, in order to set the parameters for wage increases, the labor and tax bureaus of Qingdao evaluated Haier's performance; a percentage of annual profit increases often were allowed to be transferred to employees, effectively setting an official ceiling on all raises. Avoidance of inflationary pressures was also an important goal. Distribution of profits operated according to a complex hierarchy of law and custom: the payment of local and national taxes received first priority, followed by reinvestment into Haier's facilities and interests; finally, employee welfare and public programs came third, including unemployment compensation, pension funds, and medical insurance; the company did not provide daycare for employees with children. Though the involvement of the government was a constant factor, Haier operated with a high level of managerial independence. "We work in a mixed economy," Zhang explained. "You have to have three eyes: one on the market, one on workers, and one on the government." When it came to 11 John Bryan Starr, Understanding China: a Guide to China's Economy, History and Political Structure (Hill and Wang, 1997), p. 81. 12 Yu, Guanghua, "The Emerging Framework of China's Business Organization Law," The Transnational Lawyer, Vol. 10, no. 1, Spring 1997, pp. 39-76 at p. 74. "Financial Reforms and Corporate Governance in China," Columbia Journal of Transnational Law, 34:469, 1996, at pp. 497-498. 14 Ibid. 13 8 398-101 The Haier Group (A) consider the local market, distribution and location, and the potential to improve product quality." But, he emphasized, because the considerations could be different for every company, he adhered to no simple formula. He eventually targeted two local companies: the Qingdao Air Conditioner Factory and the Qingdao General Freezer Factory. Both were stumbling at the moment when supplies of these products were beginning to outpace demand. They could no longer compete solely on price. Inside Haier, Zhang faced little opposition regarding his expansion plans. Haier's refrigerators were so profitable and popular that in 1989 Zhang had decided to raise prices during a price war, and still they sold so fast that Haier could not produce enough. But outside, Zhang had to juggle conflicting pressures. One group in government wanted him to expand more quickly; the quality award of 1988, they believed, proved that Haier could boost local employment while generating bigger revenues and thus pay more in taxes. However, because he wanted to maintain Haier's standards and preserve its unique character, Zhang had resisted their push for rapid expansion. Another group, including politically connected upper-level managers in Zhang's potential acquisitions, argued that Haier was expanding too fast, and they objected to the simultaneous acquisition of two local companies. Zhang outlined a careful strategy for the two firms. For the air conditioner firm, Zhang planned to introduce a new product line, the split unit, in effect creating an entirely new market segment. Unlike the noisy and less efficient window units, the only style then available in China, split units could run a tube of cooled air into multiple rooms of cramped apartments. The freezer manufacturer had different, more operational problems, which Zhang planned to change via the Haier enterprise culture. Like Qingdao Refrigerator, its assembly workers had to accept personal responsibility for production quality. But a larger problem was its sales force, whose "slow season" mentalitythat only certain months and not others were good for businessmade them reluctant to pursue new customers or spend resources on advertising and marketing. The factory had almost entirely shut down and carried a huge inventory it could not seil. To municipal officials, Zhang argued that adding the companies was a compromise: it would enlarge his business moderately, but not too much. When he presented his business plans to local officials, they were immediately won over. Haier could acquire both of them, by assuming responsibility for their debt and promising to retain most of the employees then at each company. In 1991, the freezer company had the capacity to produce 75,000 units and generate revenues of 160 million RMB, while the respective figures at the air conditioner unit were 7,000 and 50 million RMB. However, careful examination of the books showed that both firms were operating at a deficit of about 15 million RMB. Reorganization The newly expanded company, renamed the Haier Group in December 1992, required a major reorganization. From her position as director of the refrigerator factory, Yang Mianmian moved into this role as Zhang's close lieutenant-in a sense his right-hand man. She set up each major product group-refrigerators, freezers, and air conditionersas an independent profit center, according to Zhang's principle of becoming the best before moving into new areas. In addition to these divisions, a number of other functional groups were created, including marketing, technology management, and monitoring. Describing her role in the new organization, Yang said, "When I see the coat is too smail, I tell Mr. Zhang we need a bigger one." He usually followed her advice. (See Exhibit 3 for organization structure in 1995.) 10 398-101 The Haier Group (A) Exhibit 4 Haier Company Culture Card Post (FRONT) Haier spirit: Work diligently to serve the country, pursue excellence. Haier style: Prompt reaction to the market. Quality concept: Superior quality products stem from an excellent work force. Principle of employment: Everyone is talented regardless of background, their skills can be utilized accordingly. Service concept: The customer is always right. (BACK) Establishment of operations (market strategy): West. First focus on Asia, then on the Fixed capital development: Building new manufacturing facilities based on market demand. Technology development: To create new markets and new life styles. Company work method: To use the "OEC" management method: finish the daily agenda before the following day, and improve each day.a Marketing concept: Establish company credibility before selling products. Expansion of international markets: Focus on difficult markets first, then the easy ones. Source: Company document. a"OEC" means "Everyone everyday has overall control and is clear on everything." SON 20 The Haier Group (A) 398-101 ASA Exhibit 5 Excerpt from Company Newsletter: Example of Zhang Ruimin's Calligraphy *-. , All E414 Andy,M 4, and be A.22,p. AF ,A1A361- man , et AAAA 2W Wyntal he Lindqzrast It is very inspiring that the words of the heart should go with love. We have learned from Liu Xiangyang, who gained his success through hard work and not resting on his laurels. From him, we have also learned what Haier's Spirit is. Facing new situations and unknown people in a remote area, Liu was never unfriendly, never complained, and never made excuses. He was self-disciplined and made the best out of the conditions he faced in order to achieve his objectives. His behavior was a shining example of the Haier spirit, as we expect to see. We need always to maintain this Spirit. With it, we will not fail. -Zhang Ruimin Source: Haier News. 21 Exhibit 6 Workplace Slogans Haier Spirit: Work Diligently to Serve the Country, Pursue Excellence. Haier Style: Prompt Reaction to the Market. C Specialization, Zero Defect. Daler MASTER Source: Produced by casewriter. cock Price (Shanghai Stock Exchange) NOVEMBER 1993 - MAY 1995 30 25 20 15 10 Copy of CHINA TOTAL MARKET INDEX 5 QINGDAO HAIER O 8/31/94 11/30/94 2/28/95 Source: Datastream Fraded only in Chinese currency. The Haier Group (A) Is Exhibit 9 Haier-sponsored Public Activities Set up a "Hope" primary school for the new generation of the nation, helping the children in poverty return to school for a modern education, enabling them to choose their future as the others. @ 448 #f ENE Established a popular science magazine "Juvenile's Electric World" enabling the children to receive scientific knowledge in reading. HANS TV cartoon series "Good Haier Brothers" sponsored by Haier Group, in amusement teach children something about the nature and human existence. , Haier's Children Troupe performs many good operas, such as "I Love My Class," "Chen Xiaohu," and so on for children. Haier's "Elder Sister" restaurants provide customers with both Chinese diet culture and quick-lunch. 0 Source: Haier Company Annual Report, 1997. 25 398-101 The Haier Group (A) empty in anticipation of future growth. (By 1997, all the empty area would be covered by new projects.) Following the slowdown after the Tiananmen Square incident in 1989, consumer demand in China had revived and its growth showed no signs of slackening. $ Zhang, a charismatic man and at six feet unusually tall for a Chinese, had become something of a business celebrity in China. In the coming decade, he hoped to establish Haier as a brand name as well known worldwide as Matsushita or General Electric, and was determined to enter the Fortune 500. In 1995, Haier also began to set up a refrigerator and air conditioner plant in Indonesia. This foreign factory represented the final leg of Zhang's one-third-by-three strategy, according to which Haier would divide its business equally between sales in the domestic market, exports, and foreign sales generated by overseas manufacturing facilities. The Haier Group's success to date was due, Zhang believed, to the "Haier enterprise culture," which encouraged (and enforced) personal accountability, while combining high quality, quick service, and meticulous attention to customer preferences. In Zhang's opinion, the most important factor of production was human capital, and the role of management was to develop it. Zhang strove to emphasize innovation ("take different approaches to traditional and exceptional problems") and to learn through partnerships with international firms, such as Liebherr of Germany, Matsushita of Japan, and Merloni of Italy. In China, Zhang sought to grow Haier primarily through the acquisition of poorly managed companies with good products in promising markets. Haier would transform the acquired companies by instilling its enterprise culture and using its self-described McDonald's method" of imbuing a wide array of separate facilities with uniformly high quality. Haier was in the vanguard of an officially sanctioned trend toward company mergers and industry consolidation as China sought to restructure its economy. So far the strategy had been successful, but Zhang was still debating whether it would work at Red Star. About one-third the size of the Haier Group, Red Star would dwarf the company's previous acquisitions. (See Exhibit 1 for sales, income, profit, products; see Exhibit 2 for RMB-U.S. dollar exchange rate.) Haier's Beginnings In early 1984, while walking near his office in the Household Appliance Division (HAD) of the municipal government, Zhang Ruimin noticed lines of people waiting outside a run-down plant, the Qingdao General Refrigerator Factory. As vice general manager of HAD, Zhang helped to oversee the plant. Why were the people waiting there, he wondered. Many of them had come in from the countryside, which was flush with cash from crop sales under the reforms of Deng Xiaoping. They wanted refrigerators so badly, he soon realized, that they were prepared to buy them as soon as they came off the assembly line, unwilling even to wait for local stores to stock them. Prior to Deng's reforms, which encouraged factories to increase production of household appliances, they were rarely available and difficult to buy, often requiring "connections" with influential clerks or bosses.1 In 1981, for example, there were only two refrigerators per 1,000 city households.2 Zhang was witnessing, he believed, the birth of a new consumer market. What Zhang saw got him thinking. A refrigerator could save homemakers up to two hours per day, which they were accustomed to spending in search of fresh food. Yet despite this demand, the 1 Fox Butterfield, China: Alive in the Bitter Sea (Bantam Books, 1982), p. 108. 2 "China Survey," The Economist, November 28, 1992, p. 4. 2 The Haier Group (A) 398-101 C. Qingdao factory hovered on the verge bankruptcy. No effective leadership had emerged within the company. Because components were frequently missing, he knew, the factory rarely ran at capacity, and often shut down completely. Many of the refrigerators that came off the assembly line were ugly and scratched, with doors that wouldn't close properly. Moreover, the company offered virtually no on-site repair service. Because the factory often ran out of spare parts, returning a defective refrigerator was no guarantee it could be replaced or fixed. Even worse, new Chinese manufacturers were beginning to offer similarly inexpensive refrigerators, a competition that was sinking Qingdao General Refrigerator. Nonetheless, when refrigerators became available, consumers instantly lined up for them. Zhang decided, almost immediately, that this tiny factory represented a way to prove himself. Though he had a steady job-as the vice general manager of HAD, responsible for control and approval of technology for new productshe found his administrative duties boring and too easy. Zhang chafed under the old command style system of the Household Appliance Division; being told what to do from above, he had virtually no opportunity to try out his ideas. And he had lots of ideas. I wanted to take just one factory, and make it the best. I wanted to train people in quality assurance and production. Then I wanted to expand, with young people who were willing to learn and adapt." Zhang's Background Zhang's parents were workers without influence or connections in Qingdao. From an early age, they encouraged their son's desire to change things, to make a difference in society. "They taught me that my beliefs can be realized," he said. Like many Chinese families, they emphasized education as a means of advancement; his given name, Ruimin, meant "sensitive and intelligent." Zhang excelled in ancient literature and philosophy, learning to read the Chinese classics of Confucius and Laozi in their original form. He was becoming, in the time-honored mold, a poet and philosopher with an appetite for practical accomplishment. Upon graduation from Qingdao high school in 1968, his world abruptly changed. The Cultural Revolution, a national campaign to sweep away "old thinking," had closed down most schools and universities. Scouring the countryside and entering private homes, Mao Zedong's Red Guards smashed countless irreplaceable antiques and destroyed historical sites. Entrepreneurs, shop owners, and millions of innocent people were denounced as capitalist roaders, many of them forced to kneel in broken glass or beaten to death in front of their families. With the exception of the Red Book, a collection of Mao's writings, most older books were confiscated or burned. All of Zhang's academic achievementshis elegant and much admired calligraphy, the memorization of ancient texts, his poetry--were suddenly viewed as "feudal" remnants that hindered China from a glorious future. As a result, Zhang was forced to enter a metal processing plant, giving up his dream of higher education and scholarship for the next 20 years. He never left Qingdao. The plant he entered was run in the Soviet style, as a tiny cog in the centrally planned economy. No individual initiative could be taken, and no deviations from the yearly plan would be entertained by top management. In fact, aside from a few "rush periods" to meet its monthly quotas, the factory rarely functioned at capacity. As the Cultural Revolution degenerated into a chaotic civil war between Red Guard factions, many of the qualified personnel were removed or demoted, further crippling the factory. Zhang, who was a highly energetic and ambitious youth, sank into years of frustration and forced idleness. Like many of his generation, it only heightened his passion to excel; See Jung Chang, Wild Swans (Anchor Books, 1991). 3 The Haier Group (A) 398-101 For Zhang, Deng's policies opened a new world as well. As books and ideas began to flow into China, he devoured the literature on American and Japanese management. He found many parallels to Chinese philosophy. The advice of Harvard Business School Professor Michael Porter, in his Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors,5 melded neatly with the battlefield wisdom of Sun Tzu: product differentiation, with constant sensitivity to customer needs, was one way to achieve success in the market. It was strikingly similar to Lee laocca's marketing advice: when aiming the gun, Zhang said, you have to follow the target. Zhang was particularly impressed with the Total Quality Management system of General Electric, under the direction of CEO Jack Welch. As Zhang explained, GE's enterprise culture emphasized the personal responsibility of employees for continual innovation. In one unit, Zhang recalled, two quality engineers led the effort to improve GE products; they monitored their production line so well that they didn't need inspectors. By leading themselves, funneling their energies in the company," Zhang explained, "they were realizing their identities. I wanted to do the same in my company." Zhang also wanted a sense of common purpose to discipline employee initiative and action; he concluded that a culture center would be the organizational instrument to unite individual efforts into a coherent strategy. Zhang also studied The Fifth Discipline: the Art and Practice of the Learning Organization, by MIT Professor Peter Senge, particularly Senge's diagram of a cohesive organization, with individuals working in a consistent overall direction like the coherent light in a laser beam or a jazz ensemble performing "in the groove"?as in the Confucian way, rather than as a disparate collection of individuals in conflict. D Qingdao Refrigerator Once Zhang made up his mind to take over the Qingdao General Refrigerator Factory in 1984, he began to plot a long-term strategy. Following the example of the Japanese giant Matsushita, Zhang aspired to become nothing short of the number one refrigerator manufacturer in China. He would accomplish this, he promised, within 10 years. Then," he said, just as Matsushita had done, I will move on to other products." Because Qingdao General Refrigerator appeared in dire straitsit was operating with an annual deficit of 1.47 million RMB and with a debt of US$168,000it was not difficult to convince his colleagues in the municipal government to appoint him president. If he did poorly, they could always fire him. The first thing he needed to do was build a team, but few appeared willing to risk losing secure jobs for the uncertain future of managing a failing refrigerator plant. Nonetheless, in the wake of the Cultural Revolution, Zhang understood that many people of his generation longed for a productive work environment and were prepared to completely dedicate themselves to the right cause. One of his most capable colleagues in the Household Appliance Division, Mrs. Yang Mianmian, was immediately interested. I told her I believed in her, and that was what she needed most then," Zhang explained. An engineer and later a government official reporting to Zhang, Mrs. Yang brought formidable managerial skills to the new organization. At the same time, she was unstintingly cheerful and even impish at times. Though her given name, Mianmian, meant "soft like a lamb," one of her colleagues said: "She ruled with a steel fist." She would be key to his efforts to grow into a large conglomerate. By coaxing two other executives from 5 The Free Press, 1980. 6 Doubleday/Currency, 1990. 7 Ibid., pp. 234-5. 5 398-101 The Haier Group (A) Co the municipal government into the company, Zhang's leadership team was in place by December 1984. Zhang turned to the values he wished to instill in the organization. Although demand for household appliances seemed certain to expand for the foreseeable future, Zhang believed that competing solely on price was a losing tactic in the longer term. Many other competitors were already offering virtually identical products, and once the expansion of the consumer economy slowed, a price war was sure to follow. With the low-quality goods then available, there would be little reason for consumers to stick with any given brand. Besides, foreign firms with far better reputations for quality than Chinese manufacturers were already eyeing the market. Zhang was convinced that Chinese customers were sophisticated enough to desire higher-quality items and reliable service, and that was how he decided to distinguish his company. The real problem, he understood, was in the minds of the workers in the Qingdao General Refrigerator Factory: "They were not used to thinking about how to do a good job or take personal responsibility and initiative. Their refrigerators came off the assembly line in terrible shape, and they had no idea what good service was." If employees felt personally responsible for maintaining quality and creating value, he thought, the market would recognize this; a system of accountability, along clearly defined lines of responsibility, would also have to be put in place. It was the kernel of what became Haier's enterprise culture. Because of the legal status of the factory-it was a "collective enterprise" whose ultimate authority was the municipal government-Zhang was not allowed to fire a large portion of the 1,200- person work force. It would create too much local unemployment. Besides, though not clearly defined, the collective enterprise "belonged" to its workers, who enjoyed certain rights to be negotiated under the watchful eye of the municipal government. Unlike state-owned enterprises, however, the government did not own, or have any claim-other than taxesto a collective enterprise's assets and profits. Assuming he could turn it around, Zhang would be able to re-invest most of the factory's profits into the company. In the meantime, however, the factory had to borrow from surrounding villages to pay for workers' salaries.8 When workers in the Qingdao General Refrigerator Factory failed to improve quickly, Zhang knew they needed a shock. Early in 1985, while inspecting the refrigerators in stock, he pulled out 76 that were flawed in some way and ordered workers to smash them. The move reverberated not just within the factory, but throughout the Chinese retail world as wellworkers couldn't believe Zhang would waste their inventory of refrigerators, some of which were only scratched, while financial losses remained enormous. That got their attention," Mr. Zhang laughed. "They finally understood I wasn't going to sell just anything, like my competitors would. It had to be the best." With that, factory workers and managers were ready to take a second look at how the company operated. With only an idea, he explained, "the workers opened their minds." Zhang strove to instill discipline by example. He routinely worked 14-hour days; to save money while the company's financial situation improved, he took public transportation to work and stayed in inexpensive hotels on business trips. To complement the uniforms of the factory workers, Zhang's managers adopted a common dress code: blue ties and pin stripe suits with leather loafers; the only variations in evidence were the color of sweaters that managers chose. At one point, while experimenting with a smoke-free workplace to enhance worker productivity, all of the company's top 8 Fons Tuinstra, "From Rags to Riches: Haier Group Asserts Its Independence," Deutsche Press Agentur, August 21, 1996. Kathy Chen, "China Refrigerator Maker Stickler for Service Quality," Asian Wall Street Journal, September 18, 1997, p. 1. 9 6 The Haier Group (A) 398-101 in order executives quit smoking. In 1988, Zhang returned part-time to his studies, a correspondence course for the Chinese equivalent of an MBA. To reinforce the attitudes he was cultivating, Zhang established an evaluation system that linked performance to wages and promotions. He sought to make the company's processes more efficient. Following "Time Operation Research," a modern version of Taylorism, Zhang and his team went over every procedure in the factory, gauging what was necessary and what wasn't. "Other companies [in China] didn't do this much research," he said. "We constantly sought to make things better in some way." A parallel inquiry analyzed the work routines of the company's managers. Time Operation Research offered a way to measure employee performance and became the vehicle for the company's "point wage system," an "objective" appraisal system indexing job complexity and difficulty-whether "heavy, light, or skilledagainst quality of work and service.10 Every month, all employees submitted themselves to this assessment. The better performers were entitled to higher wages and, eventually, more responsible positions. The assessment was also employed to evaluate employees' aptitudes for their current positions, which often resulted in job transfers. Errant or sluggish workers could be subject to heavy fines, sometimes up to half of their wages, and were forced to explain their failings to their immediate colleagues. It was Zhang's way of introducing competition into the workplace, tying ambition and personal initiative to the wage structure. But worker attitude was only the beginning. Another cornerstone of Zhang's strategy was the factory's foreign partner: Liebherr-Haushaltsgerate of West Germany was ready to inject modern refrigerator manufacturing technology into the plant. "First we observe and digest (the new methods)," Mr. Zhang explained. Then we imitate it. In the end, we understand it well enough to design it independently." The company would never, he emphasized, become dependent on regular infusions of foreign technology. The collaboration worked so well that, in 1985, the collective chose Haier as its new name, a direct translation of Liebherr, or "Dear Sir," into Chinese. The company's logoa dark- haired Chinese child with his thumb pointing upward as number one" embracing a blond European gaminealso symbolized the union. In a later collaboration, Haier licensed refrigeration technology from Mitsubishi of Japan. However, Haier engineers created the first convertible freezer compart- ment on their own. The units could serve both as cold storage in the summer and as a freezer unit in winter, when Chinese consumers sought to preserve otherwise unavailable seasonal food stuffs. Zhang rewarded his best workers with places at the newest assembly lines. Within the first year, Haier almost broke even, and in 1986 turned a profit of 1 million RMB. By 1988, with sales steadily improving, it won a gold medal for quality from the Chinese Quality Management Association, a state organization. By 1991, Zhang reached his goal: Haier became the number one refrigerator manufacturer in China, both in terms of sales at 309,000 units (830 million RMB) and recognized quality. "Now," he said, "we could let our reputation precede our new products.... ... It was time to diversify... and seek international quality assurances." With the success of Haier, Zhang's leadership was undisputed, both within the company and by officials in the municipal government. He turned his attention to consolidate what he had learned in order to expand into other product lines. Governance of Collective Enterprises As a "collective enterprise," Haier operated within a legally ambiguous system of governance. A fixture of post-1949 China, collective enterprises had been designed to allow groups of artisans and 10 See James Harding, "Rising Star in China's Infant Corporate Culture," The Financial Post, November 21, 1997, p. 69. 7 398-101 The Haier Group (A) small entrepreneurs as well as neighborhood unitsthe "danwei"to band together for purposes of commercial activity, farming, and transportation. Avoiding the capitalist overtone that "private" implied, their ownership was "collective" in the sense that together the members in theory owned all production facilities. 11 Approval to operate, merge, dissolve, divide, or make other changes had to be secured from government authorities in charge of collective enterprises as well as from local officials of the State Administration of Industry and Commerce. 12 In 1997, China had approximately 25 million collective enterprises, employing 500 million. In most collective enterprises, two poles of authority had evolved in practice: (1) the company managers who handled business strategy and the majority of day-to-day operations, and (2) the managers who handled personnel issues and monitored the company from a political point of view. The influence of the Communist Party was felt most directly through the second channel. Nonetheless, the lines of authority were almost never clearly spelled out in either the company articles of association or its ownership structure. The larger collective enterprises, according to Yang Mianmian, tended to operate as "closed information systems," unaccustomed to seek or accept information from outside sources. During China's period of Soviet-style planned economy, collective enterprises developed habits ill-suited for a market economy: among these were preferences for quantity over quality and sales forces unaccustomed to seeking new customers. The enterprises took their existence and survival for granted. Though China's bankruptcy law dated to 1986, only 2,000 firms had filed for bankruptcy nationwide by 1995.13 Neither banks nor governments were willing to force bankruptcies. Banks feared their bad loans would never be repaid, and governments feared the social and political consequences.14 As many collective enterprises expanded into much larger entities, the laws governing their management and operation evolved in a murky and ill-defined process, often according to established custom and negotiation with local politicians. Though no longer a government administrator, Zhang as Haier's chairman and CEO was still considered an appointee who served at the pleasure of the municipal government. He could in principle be fired for any reason-poor profitability, labor disputes, or mismanagement of funds. Every year, in order to set the parameters for wage increases, the labor and tax bureaus of Qingdao evaluated Haier's performance; a percentage of annual profit increases often were allowed to be transferred to employees, effectively setting an official ceiling on all raises. Avoidance of inflationary pressures was also an important goal. Distribution of profits operated according to a complex hierarchy of law and custom: the payment of local and national taxes received first priority, followed by reinvestment into Haier's facilities and interests; finally, employee welfare and public programs came third, including unemployment compensation, pension funds, and medical insurance; the company did not provide daycare for employees with children. Though the involvement of the government was a constant factor, Haier operated with a hStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts