Question: Sameera was starting her first professional assignment as a Management Trainee. She had graduated from the country s leading health management institute. She was always

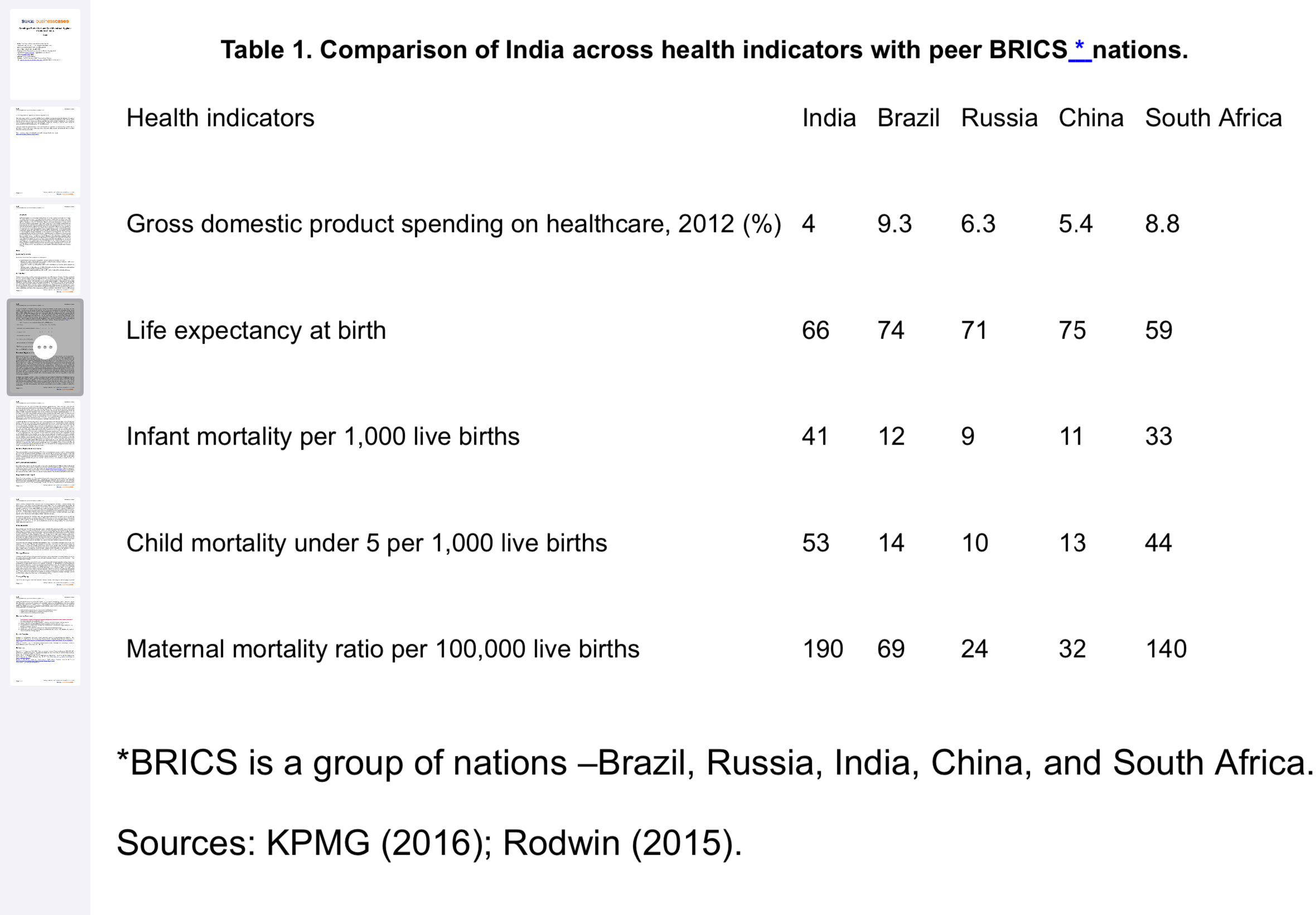

Sameera was starting her first professional assignment as a Management Trainee. She had graduated from the countrys leading health management institute. She was always fascinated by challenges and the promises that health management offers in a country such as India. During her Masters in Health Management MHM course, she was struck by the dismal health indicators in India, primarily the gender disparities in health indicators. She was always astounded by the belief system that had made some of the physiological phenomena related to women mysterious, and now the data were staring her in the face, showing the damage of these longheld cultural beliefs. During her MHM program she had decided to work for the improvement of womens health. Menstrual hygiene management was an area where she wanted to make a substantial contribution. She began working for an organization called Better Tomorrow BT working for an improvement of womens health and incubating the business models related to the same. She was ecstatic, nonetheless a chill passed through her spine when she considered the magnitude of the issues confronting womens health in India. After successful completion of two months training, the Chief Executive Officer CEO of BT called Sameera. She was a bit anxious before the meeting as she was unaware of what was there in the offing. The CEO made her comfortable and then asked her, are you ready to take up a challenge? she responded in the affirmative. The CEO continued, can you please create a strategy for the sustainable adoption of lowcost sanitary napkins by women in the district Sultanganj in the central province of India? Sameera started comparing health indicators in India with those from BRICS nations. She realized the gravity of the situation and the magnanimity of the task in the field of menstrual hygiene.

Menstrual Hygiene in India Menstruation is a natural bodily process of womans health cycle. It indicates womens reproductive health. However, in India, the extent to which menstruation is considered a normal health issue that can be discussed openly differs amongst women from different socioeconomic strata. For women from the underprivileged socioeconomic background, menstruation becomes the most dreaded time of the month. Menstruation is shrouded in deeprooted taboos associated with myths describing menstruating women as impure, filthy, sick women are even said to be cursed during their periods. It is viewed with shame and treated with secrecy in India. Women are confined to certain spaces, marked for the purpose, outside the main living space in the house premises during their menstrual cycle. Their movements are restricted, and their need to stay clean and dry is neglected. As a result, women from poor rural and urban households often experience poor reproductive health and increased maternal mortality compared to wealthier women in India. Women are isolated from family, friends, and their community even other women due to the social stigmas associated with their menstruating bodies. They cannot enter kitchens, temples; cannot perform rituals and participate in festivals; they must eat with different utensils and are barred from touching pickles, for fear they will turn the food rotten. In a study by the Indian Council of Medical Research, it was found that of mothers consider menstruation as dirty and polluting Many teachers and frontline health workers echo the same sentiments Lack of management of menstrual hygiene, both due to misinformation and structural issues such as not having safe and dignified sanitation facilities, becomes a cause of girls dropout from school. One in five girls in India drops out of school due to menstruation. Adolescent girls in India miss up to days of schooling in a year due to the lack of menstruation care. It also compromises womens ability to engage in productive employment.

Traditionally women use cloths to manage their menstrual hygiene in India. These cloths are cut out from the used sarees and lungis which are the conventional dress of Indian men and women. In small homes, the lack of private spaces makes it difficult to clean and dry these cloths. Thus, women reuse soiled cloths rather than replacing them frequently, and become prone to infection. Wearing the same soaked fabric all day at school or work causes outer clothing to stain, adding to shame for young girls and the pressure to drop out from school. Left unchecked, infections can cause heavy bleeding and subsequent chances of anemia which is very common amongst Indian women. Some reports state that tribal and rural women go to the extent of using dirty rags and mud to check the menstrual flow. In some extreme cases leaves, dung, and animal skins are used to manage the menstrual flow. In a study conducted by A C Nielson and Plan India, of menstruating women were found to be using old unsanitized fabric, rags, or sand. A woman spends on average days of her life menstruating, so the ability to care for herself and stay healthy during this time greatly affects her educational development and social mobility. Health conditions for women in rural areas are different from that of urban areas since women from rural areas may not have known the use of sanitary napkins and may not be aware of it As per some reports in out of million menstruating women in India, only use storebought disposable sanitary napkins. However, the National Family Health Survey report for suggests that of women in urban India uses hygienic means to manage menstruation as against only in rural India. As per this report overall of Indian menstruating women use hygienic means for menstruation management. However, in rural India only of the target population use disposable products. Menstrual cups and tampons are not preferred in India due to cultural reasons, where societies do not accept internal application of sanitary protections, especially before marriage. Medical practitioners are of the view that sanitary napkins can help prevent reproductive tract infection. Sanitary napkins can also reduce the risk of cervical cancer, and lower the occurrence of ailments such as urinary tract infections. Sanitary napkins are expensive, and cost is not the only barrier that inhibits women from buying quality napkins. Other barriers are discussed in the section below describing Sameeras market research. Seventy percent of women in India cannot afford sanitary napkins which on average cost INR per cycle. More than half of rural households depend on manual labor for their livelihood, and of the rural population million earn less than INR per month. With an average family size of five, per month income is around INR per day per person. Sanitary Napkin Business in India The sanitary napkin industry makes up only of the fastmoving consumer goods market. Industry experts believe that due to its lower market penetration it may see a growth rate of around percent for the next five years. The sanitary napkin market is expected to be around USD million. The markets in towns and cities are controlled by the established firms such as Procter & Gamble P&G Due to the high cost of sanitary napkins, sold by multinational giants such as P&G there is ample scope to develop a market for lowcost sanitary napkins. LowCost Sanitary Napkins Lowcost sanitary napkins are of highquality, on par with products offered by P&G and other multinational companies, and have the potential to revolutionize Indias menstrual hygiene market. They can be produced inexpensively thanks to an innovation of a machine by Arunachalam Muruganantham, Indias menstruation man, that simplified sanitary napkin making at the local level. Arunachalam Muruganantham has pioneered the making of sanitary napkins using raw materials such as banana fiber, bamboo, and water hyacinth pulp. Organization and Project Better Tomorrow was based out of the capital of the central province. It was established, as a not for profit organization, by two feminist activists in Interestingly, an organization had evolved over the years from being an advocacy organization to a programbased organization. It was, mainly, working in womens health and the education sectors It had three strategic business units SBUs The first unit would innovate businessideas to address womens health concerns such as anemia, reproductive health, undernourishment and breast cancer. These ideas would be incubated by another SBU here, they would analyze the feasibility of the business idea and work out the financing. A third SBU would roll out the business idea to implement these innovative solutions on a large scale. SBUs were headed by a Vice President who reported to a CEO. Each SBU has many thematic groups. Themes included: reproductive health; anemia; educationschool dropouts; and more. Thematic groups in different SBUs would work closely based on the themes they work on An SBU involved in an implementation of the innovative business idea is the largest unit with multiple field teams. Two support teams, finance and human capital, directly reported to the CEO. Sameera was working in an incubator SBU. She was spearheading a team to suggest an overall strategy to create a market for lowcost sanitary napkins. This project was very important to address multiple social issues related to womens health and education; thus, the CEO was closely monitoring the project. He wanted Sameera to report to him so he could monitor the development of the strategymaking. This made Sameera more excited about the project. Initial Research Sameera had taken the first step to strategize: market research. She was astounded by some of the results regarding barriers to buying sanitary napkins. There is a shame associated with buying sanitary napkins in India. A study by a sanitary napkin manufacturer found that in cities of women buying sanitary napkins buy them wrapped in a brown bag or newspaper. They almost never ask a male member from a family to buy sanitary napkins. Sameera found that there is a greater need to come out of this culture of shame and silence, and start discussing it openly. However, because neither families, schools, or religious communities provide basic education about menstruation, both men and women lack knowledge about menstruation, which makes things more complicated. Sameera learned that of women in rural India have no adequate knowledge about menstrual hygiene and care, and that of girls in India believe that menstruation is a disease. Sameeras research findings highlighted that affordability, ease of availability, and accessibility need to be addressed, in that order. Through her research she concluded that access to safe menstrual health is a big challenge. It is skewed towards women from higher income groups. Also, the shame associated with menstruation inhibits women from buying products from shopkeepers who are generally males. Not many shopkeepers in villages are willing to stock sanitary napkins as there is little demand for them. Notwithstanding, women in rural areas are reluctant to be seen as purchasing sanitary napkins. Strategy Dilemma Sameera was swift enough to discern several problems lack of awareness of sanitary napkins, the myths associated with menstruation, and the femaleunfriendly distribution channel. Now she had a quandary how to address these problems? Since Sameera had all the requisite information in hand she started thinking of a possible strategy to generate a market for lowcost sanitary napkins in the district of Sultanganj. Her predicament was how to persuade women to switch from their conventional menstrual hygiene practices to the use of disposable napkins they could afford. She had a discussion with Professor Suraj, one of her former professors in the marketing department. Their discussion revolved around the TT by Bagozzi and Warshaw You study how a theory of trying can be used to make a marketing strategy said Professor Suraj. He continued, the context of menstrual hygiene is an ideal context for using this theory, trying out low cost sanitary napkin is the key here. Once they try the product I am sure women will change the unhygienic practices Sameera revisited the TT and tried to figure out what could be the marketing strategy. Theory of Trying The TT focuses on goals rather than reasoned behavior choices. The theory focuses on trying to achievethese goals rather than actual attainment of goals. In TT if one is studying, say, tobacco cessation, rather than attempting to determine the predictors of successful quitting, one should first determine the predictors of trying to quitDonovan & Henley, p Using the basic principles from Bagozzi and Warshaw three factors determine an individuals overall attitude towards trying a certain behavior, in this case, purchasing a lowcost sanitary napkin: attitude towards succeeding and the expected likelihood of success. attitude towards failing and the expected likelihood of failing. attitude towards the actual process of trying.

Which audiences should Sameera target to create the market for lowcost sanitary napkins?

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

1 Expert Approved Answer

Step: 1 Unlock

Question Has Been Solved by an Expert!

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts

Step: 2 Unlock

Step: 3 Unlock