Question: STEP 1 - Either find a a quantitative research methodologies or a blind refereed quantitative research article. STEP 2 - Write 25 questions that are

STEP 1 - Either find a a quantitative research methodologies or a blind refereed quantitative research article.

STEP 2 - Write 25 questions that are specific to the article.

STEP 3 - Turn in a list of the 25 questions you created and write the APA citation for the article you read that was published by your research scholar.

Article:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6892488/

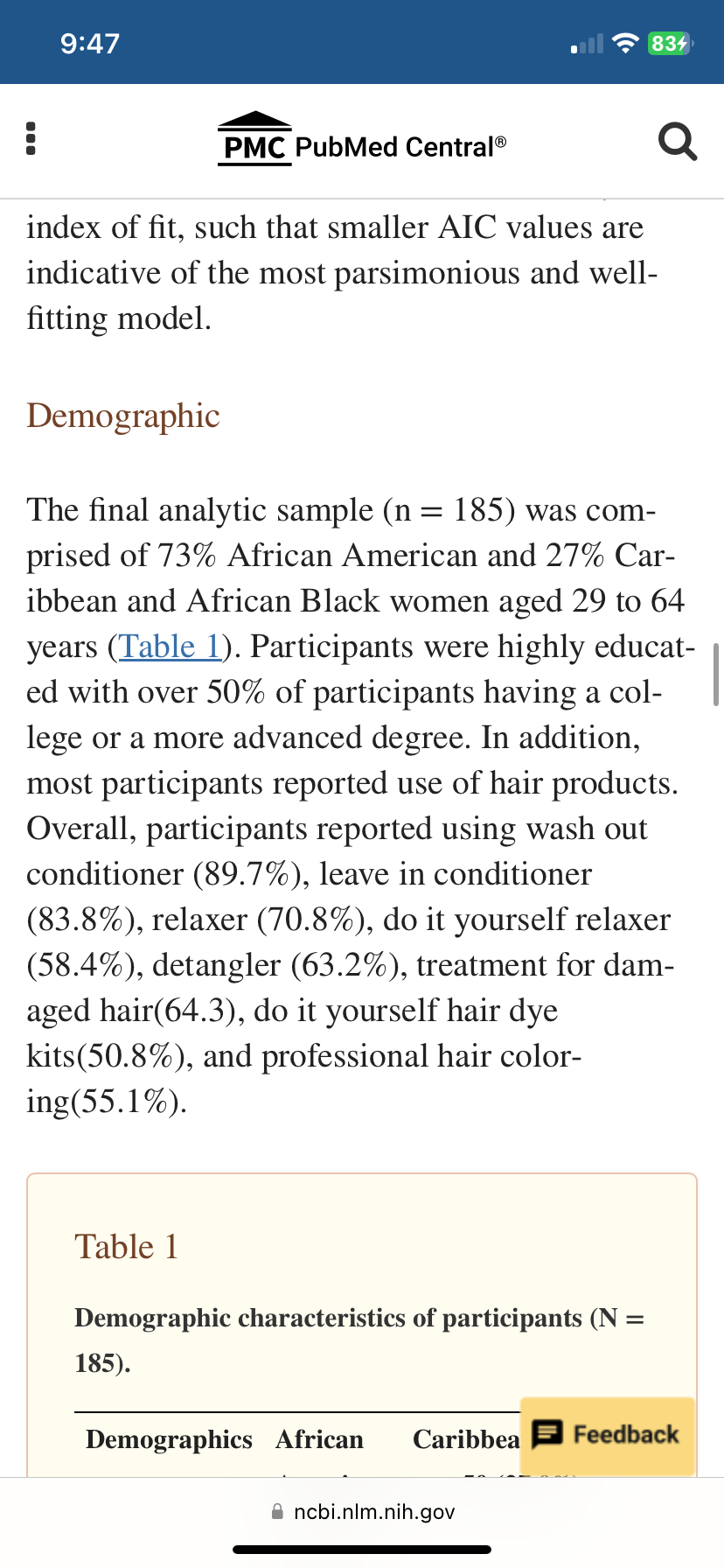

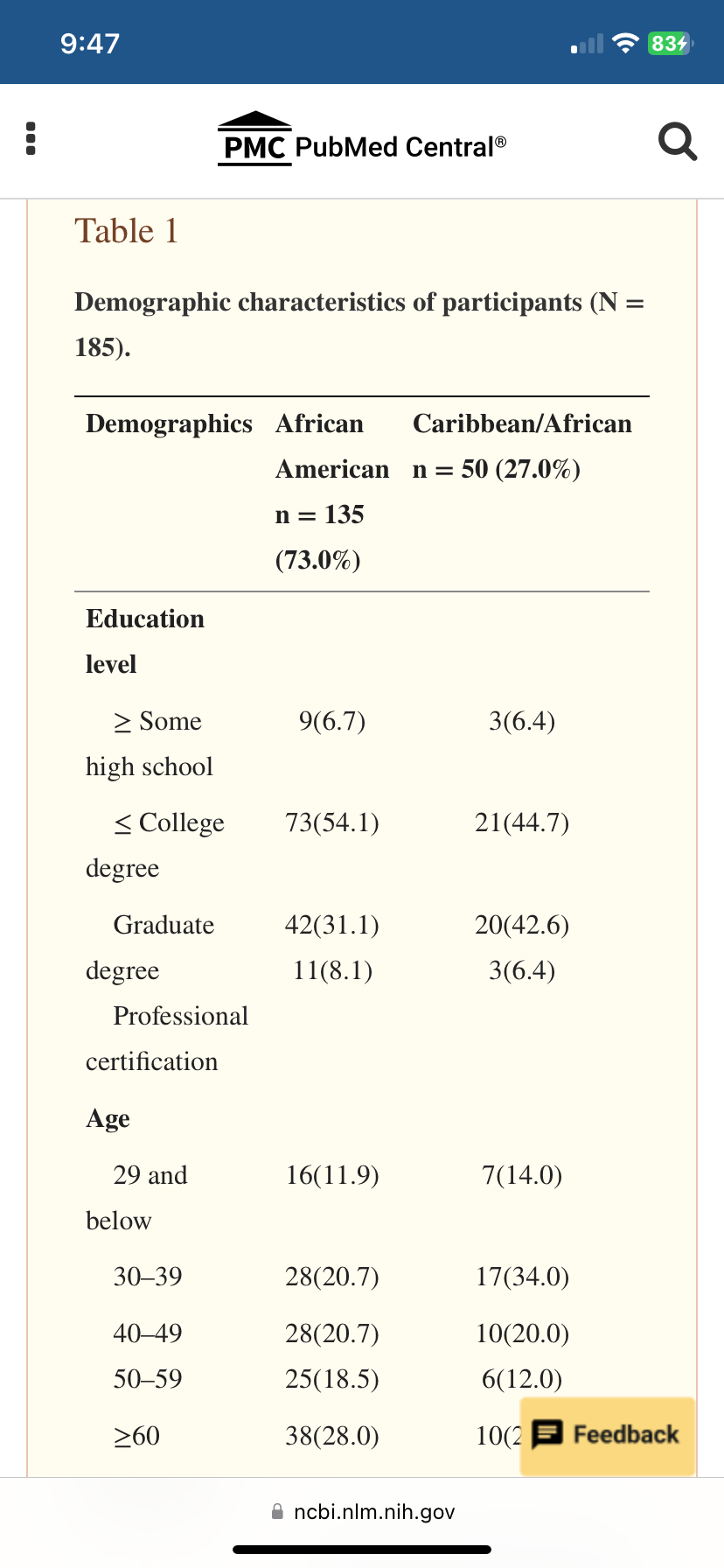

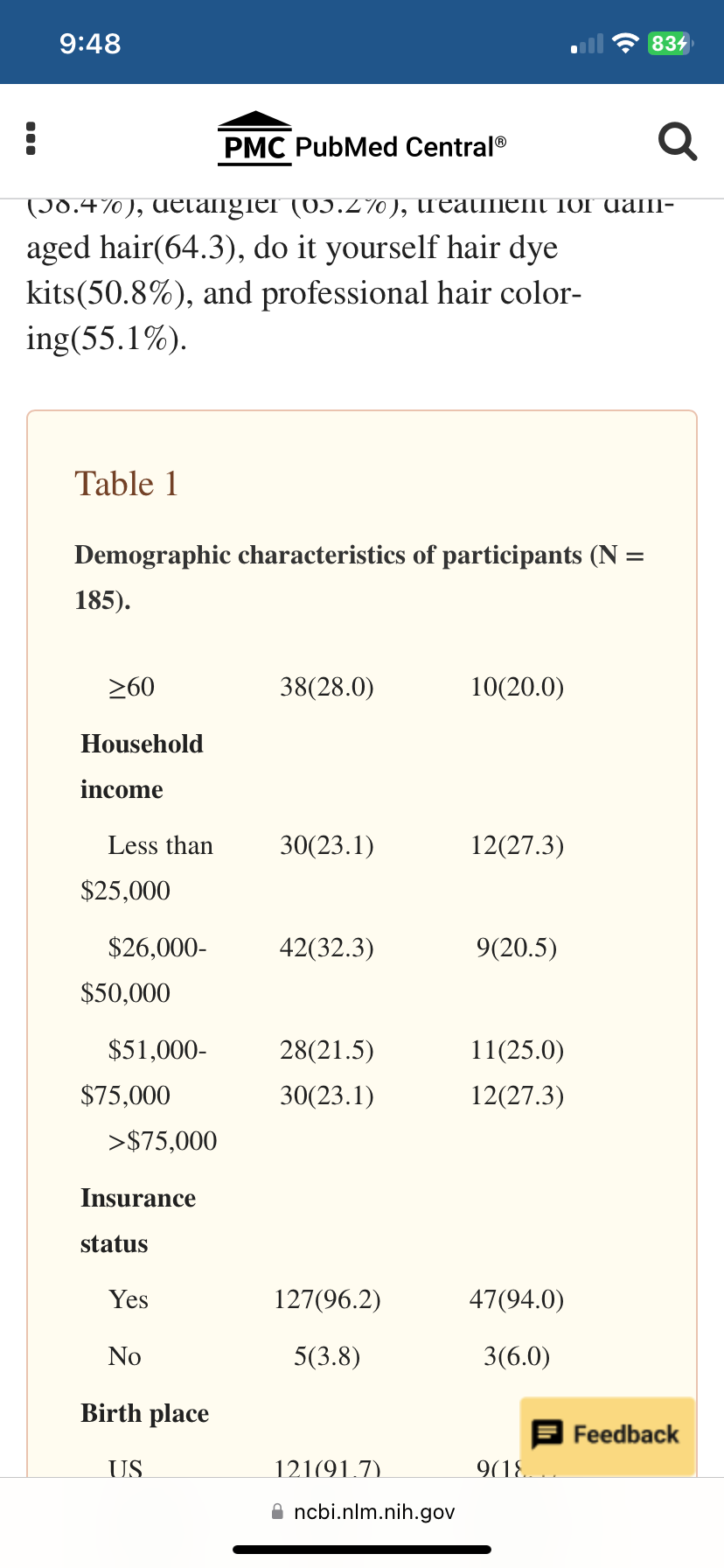

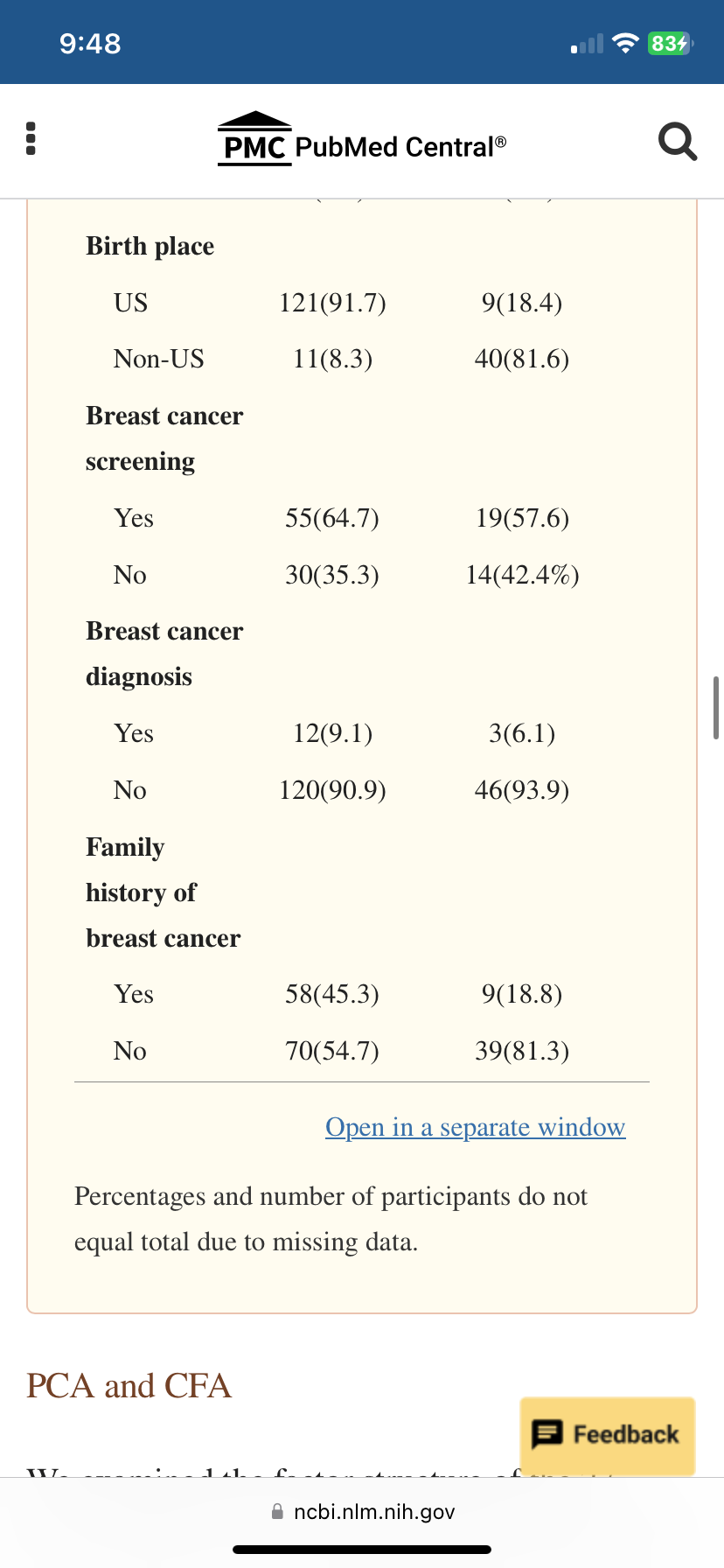

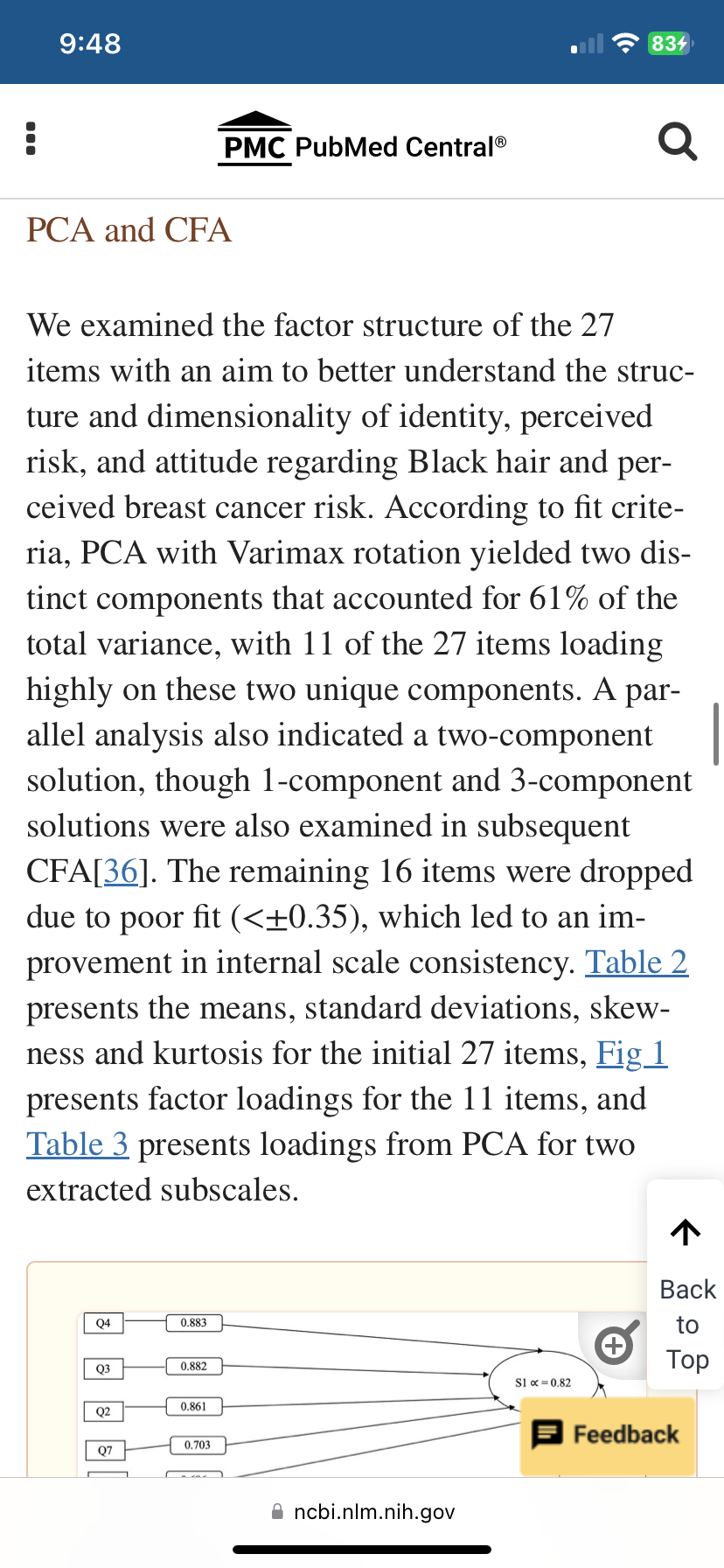

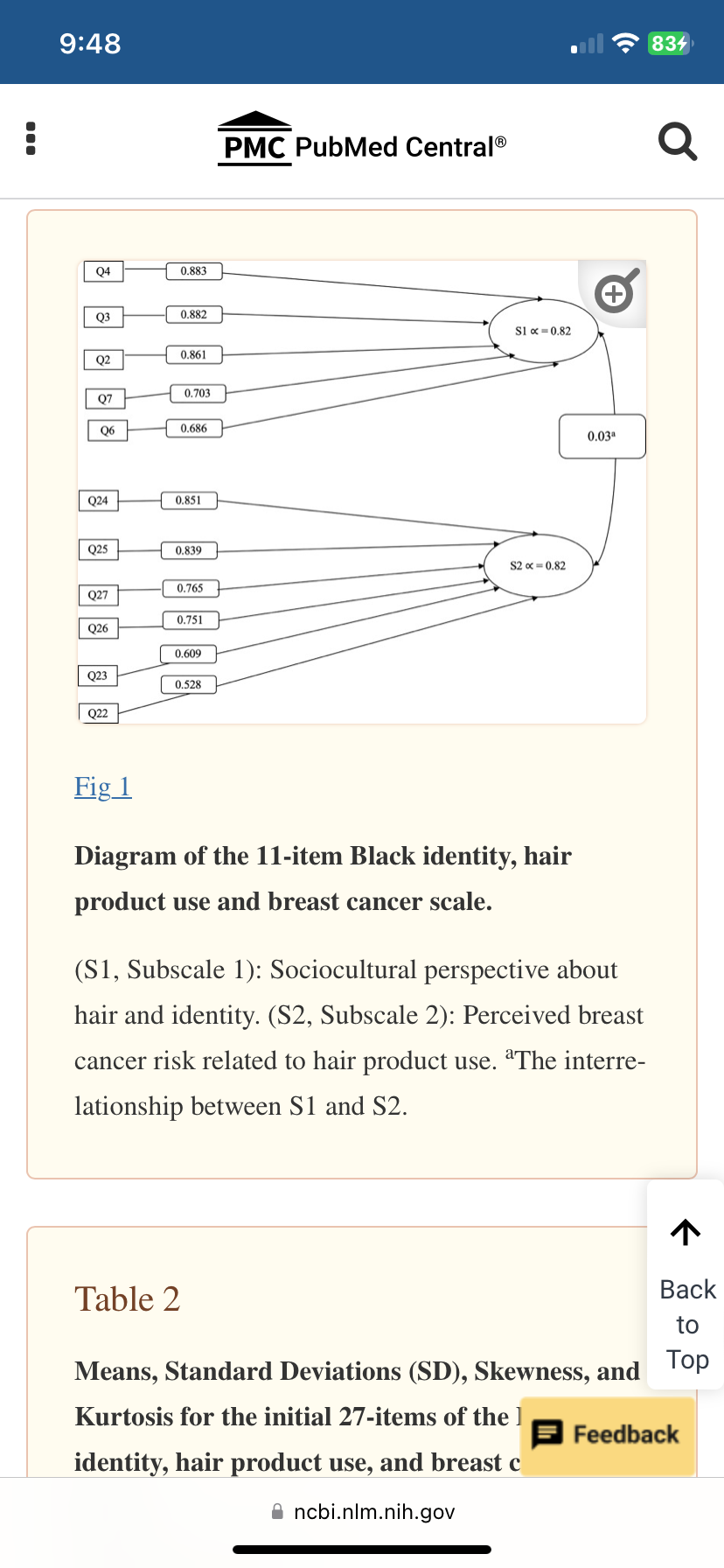

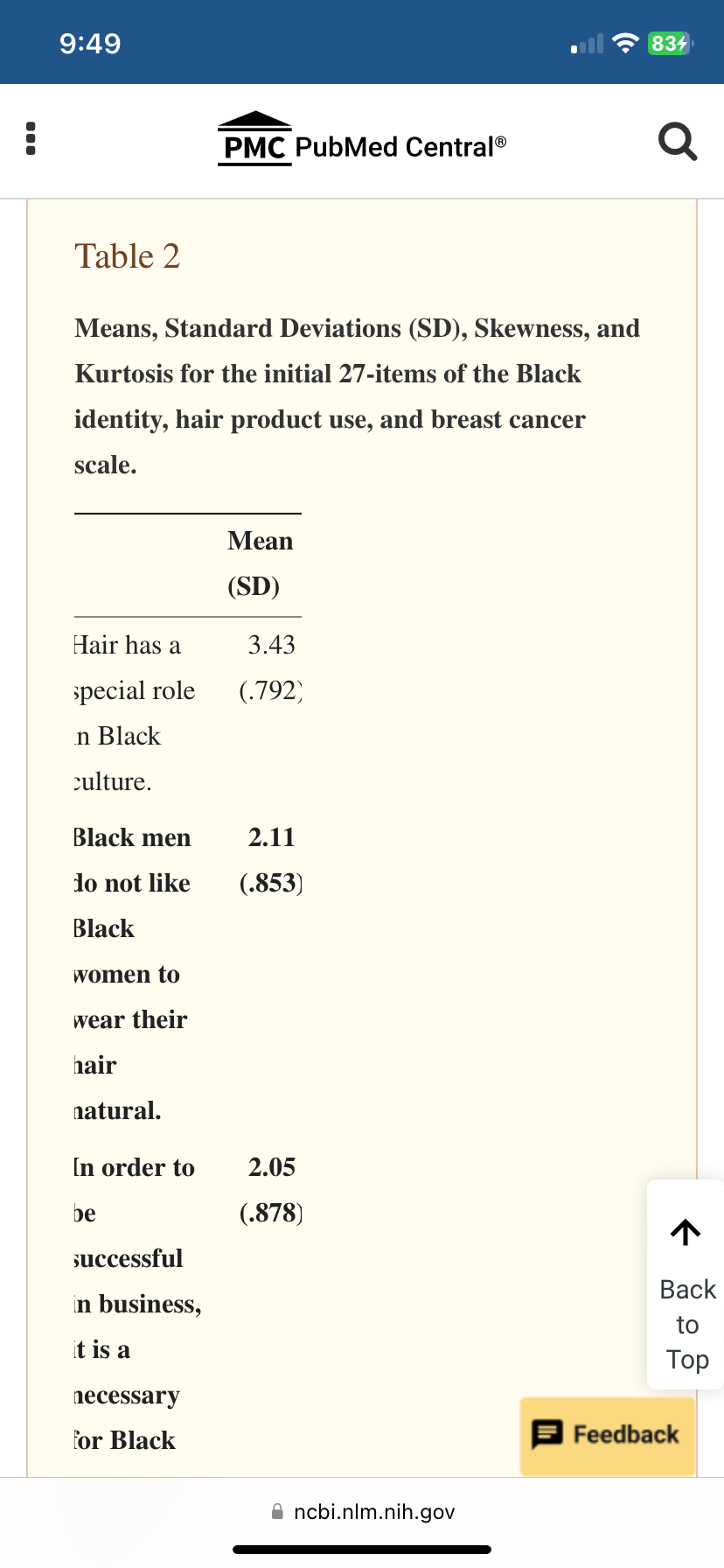

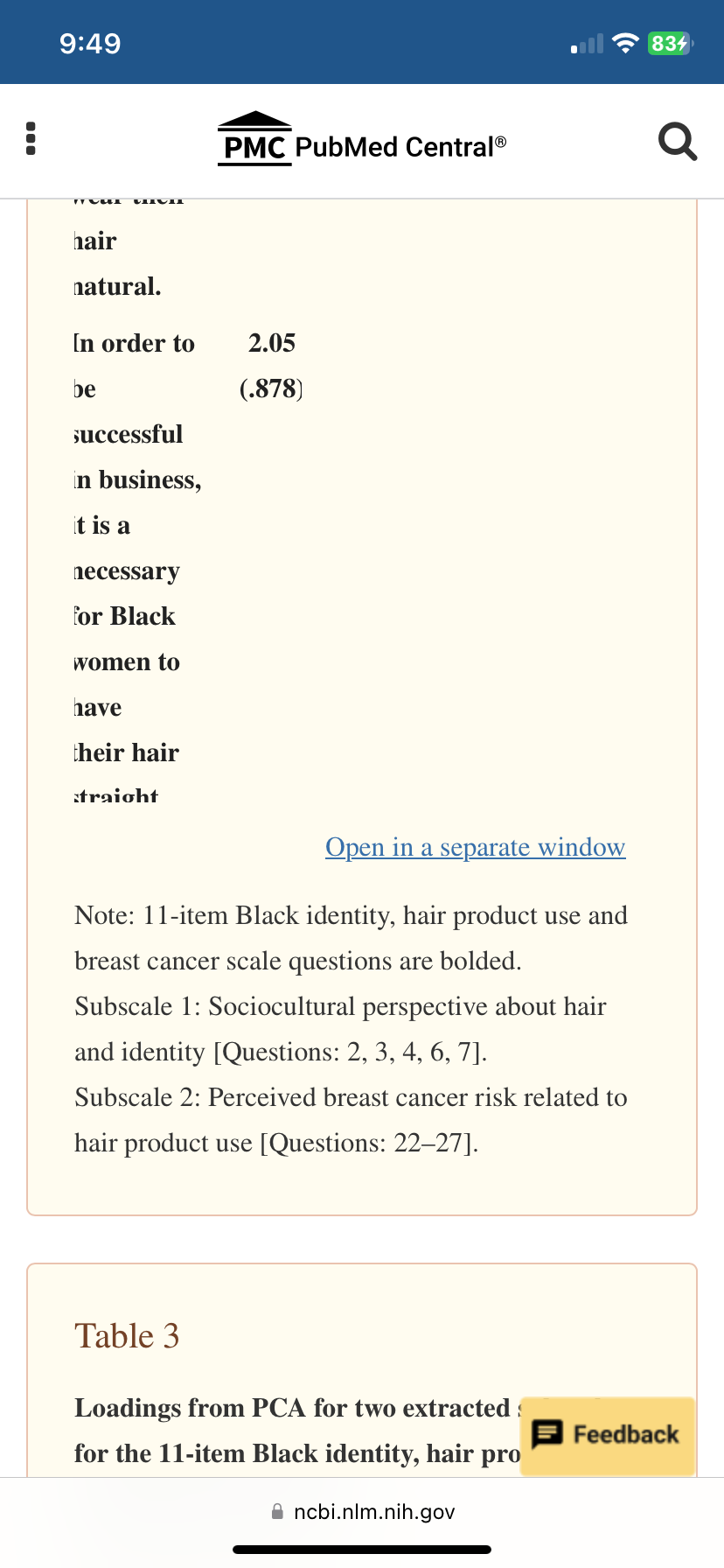

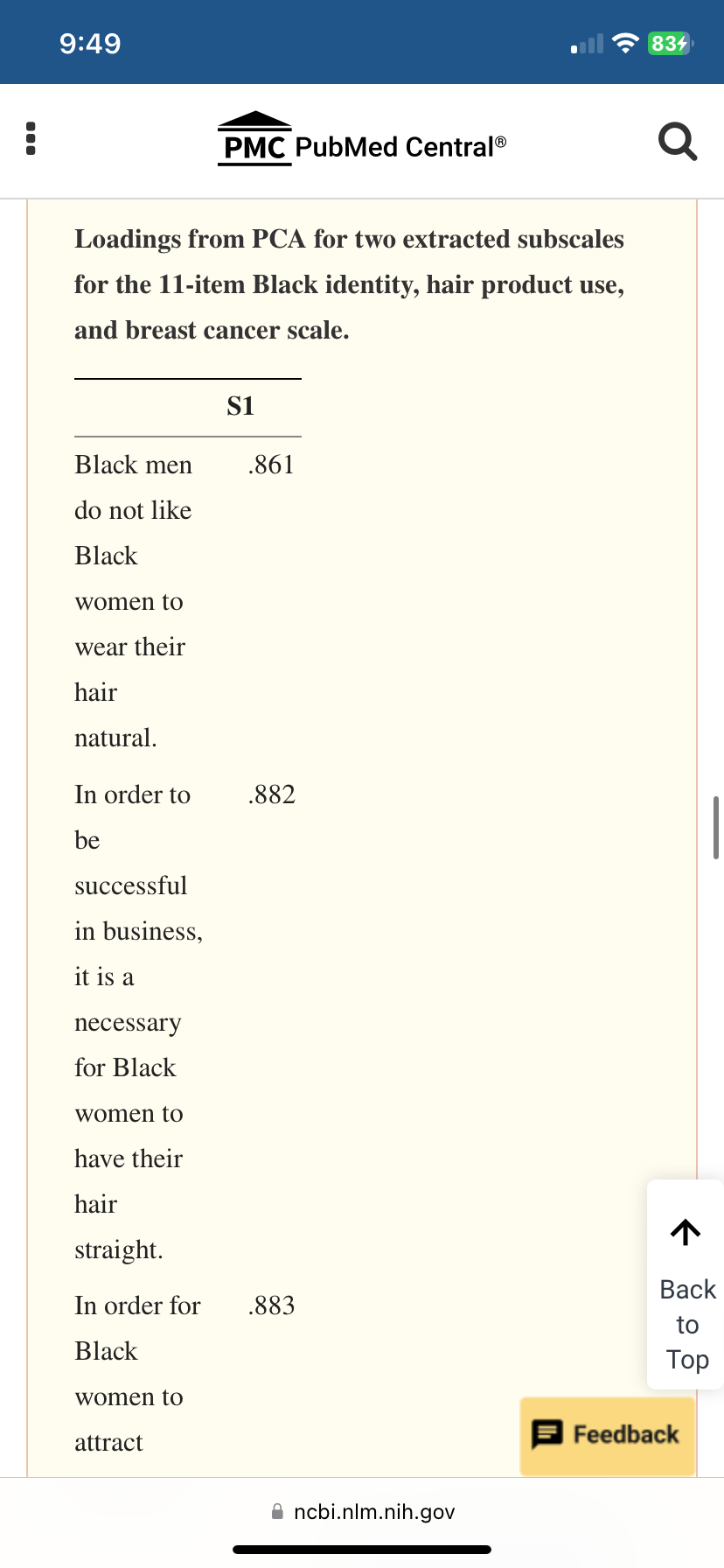

9:36 834 .. PMC PubMed Central Q The Black identity, hair product use, and breast cancer scale Dede Teteh, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, #1,* Marissa Ericson, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, #2 Sabine Monice, Writing - original draft, 3, Lenna Dawkins-Moultin, Conceptualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, #1 Nasim Bahadorani, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, 4. Phyllis Clark, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Writing - review & editing, + Eudora Mitchell, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Writing - review & editing, , Lindsey S. Trevino, Writing - review & editing, 1. Adana Llanos, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, " Rick Kittles, Writing - review & editing, " and Susanne Montgomery, Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing - review & editing#3 Cheng-Shi Shiu, Editor Feedback a ncbi.nim.nih.gov9:36 834 ... PMC PubMed Central Q Abstract Go to: Introduction Across the African Diaspora, hair is synony mous with identity. As such, Black women use a variety of hair products, which often contain more endocrine-disrupting chemicals than prod- ucts used by women of other races. An emerg- ing body of research is linking chemicals in hair products to breast cancer, but there is no validat- ed instrument that measures constructs related to hair, identity, and breast health. The objective of this study was to develop and validate the Black Identity, Hair Product Use, and Breast Cancer Scale (BHBS) in a diverse sample of Black women to measure the social and cultural constructs associated with Black women's hair product use and perceived breast cancer risk. Methods Participants completed a 27-item scale that queried perceptions of identity, hair products, and breast cancer risk. Principal Component Analyses (PCA) were conducted to establish the underlying component structures, ar Feedback tom fontor analunia (CDA ) runn wand a ncbi.nim.nih.gov9:36 834 .. PMC PubMed Central Q underlying component structures, and confirma- tory factor analysis (CFA) was used to deter- mine model fit. Results Participants (n = 185) were African American (73%), African, and Caribbean Black women (27%) aged 29 to 64. PCA yielded two compo- nents that accounted for 61% of total variance. Five items measuring sociocultural perspec- tives about hair and identity loaded on subscale 1 and accounted for 32% of total variance (a = 0.82; 95% CI = 0.77-0.86). Six items assessing perceived breast cancer risk related to hair product use loaded on subscale 2 and accounted for 29% of total variance (a = 0.82 (95% CI = 0.74-0.86). CFA confirmed the two-component structure (Root Mean Square Error of Approxi- mation = 0.03; Comparative Fit Index = 0.91; Tucker Lewis Index = 0.88). Conclusions The BHBS is a valid measure of social and cul- tural constructs associated with Black women's hair product use and perceived brea Feedback a ncbi.nim.nih.gov} PMC PubMed Central Q hair product use and perceived breast cancer risk. This scale is useful for studies that assess cultural norms in the context of breast cancer risk for Black women. Introduction Go to: Breast cancer remains the second leading cause of death in the United States among women [1, 2], with Black women being particularly vulner- able [3]. Recent reports indicate that while the incidence rates of breast cancer in Black and White women have converged [4], mortality rates among Black women are at least 40% higher than their White counterparts [3]. Fur- thermore, Black women are more likely to be diagnosed with and die from more aggressive forms of breast cancer than White women who are more often diagnosed at earlier stages [3]. Research on cancer disparities has not been able to conclusively explain Black women's elevated risk of breast cancer mortality or their more ag- gressive phenotypes, but differences in progno- sis and etiology have been correlated with race [6], genetics [7], lifestyle and behavioral factors [8], and environmental exposures [9]. B Feedback One environmental factor that has b @ ncbi.nlm.nih.gov 9:37 834 PMC PubMed Central Q increasing attention in breast cancer research is hair and personal care products [2-11]. A grow- ing body of literature [2-14] supports an associ- ation between use of some hair care products (e.g., hair dyes, relaxers, and deep conditioners) and breast cancer risk. Data from animal models [15-17] suggest exposures to compounds found in some hair products, particularly those con- taining endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDC's) and chemicals with mutagenic properties, may be important etiologic risk factors for several human cancers, including breast cancer. Stiel and colleagues' review of hair product use and breast cancer risk included research on environ- mental estrogen, EDCs, and placenta-derived ingredients found in hair products used primaria ly by African American women. The authors concluded there is significant evidence to sup- port the role of hair product use in the risk of early-onset breast cancer in Black women. In addition, Myers et al. [14] assessed ethanol extracts of eight personal care products fre- quently used by African Americans Feedback genic and anti-estrogenic activity in AA ncbi.nim.nih.gov C9:37 834 PMC PubMed Central Q quently used by African Americans for estro- genic and anti-estrogenic activity in a human breast cancer cell line. They detected estrogenic activity in oil, hair lotion, extra-dry skin lotion, intensive skin lotion, and petroleum jelly, and anti-estrogenic activity in placenta hair condi- tioner, tea-tree hair conditioner, and cocoa but- ter skin cream. The authors concluded some hair and skin care products have ingredients that can mimic estrogen functioning. Llanos and colleagues [11] also examined the association between breast cancer risk and use of hair dye, chemical relaxers, and deep conditioners in a sample of African American and White women. They found, among the dark hair dye shades, African American use was associated with in- creased breast cancer risk (OR = 1.51, 95% CI: 1.20-1.90). Despite the mounting evidence of possible health risk, hair products remain popular in the Black community [10, 11, 18]. Compared to white women, Black women invest more money on hair products [19], are more likely to use re- laxers and deep conditioners, and use them at younger ages [11, 18]. As a result, Black Women are more likely to be exposed to haw monally active chemicals in hair prc Feedback a ncbi.nim.nih.gov} PMC PubMed Central Q women are more likely to be exposed to hor- monally active chemicals in hair products across their lifespan, potentially increasing their risk for developing breast cancer [18]. The literature on Black women's attitude to their hair offers mixed explanations for the popularity of hair care products in Black communities. Some scholars suggest hair across the African diaspora is synonymous with identity, individu- ality, and beauty norms [20, 21]. For many Black women, maintaining hair with sculpting and straightening products is an extension of self and a way to achieve social acceptance [21, 22]. Alternatively, scholars such as Johnson and Bankhead challenge the notion that straight hair represents an ideal form of beauty and is con- nected to social acceptance [22]. They argue that wearing hair in its natural state is the \"new normal\" that celebrates Black identity and pride. But even products designed for natural Black hair have been found to contain potential- ly harmful ingredients [23]. So, whether Black women choose to chemically alter their hair or keep it in its natural state, they are overexposed to hair products containing endocrine disrupting and other toxic chemicalsmany of " "~ not listed on product labels as they I @ ncbi.nlm.nih.gov } PMC PubMed Central Q not listed on product labels as they are usually listed generically as fragrances [10, 24]. There is a gap in our understanding of how these environmental, sociocultural, and biologi- cal factors converge and impact breast cancer risk and outcomes among Black women. Cur- rently, there 1s no validated scale that measures constructs related to hair, identity, and breast health. Instruments have been developed to measure related but general issues, such as so- cial and personal identity [25], health beliefs [26], and perceptions of health risks [27]. How- ever, none of these instruments capture the con- structs that emerge at the intersection of social, cultural, and health-related factors. Having a validated tool that measure these latent struc- tures will provide a more comprehensive under- standing of Black women's breast cancer risk. The purpose of this study was to validate the Black Identity, Hair Product Use, and Breast Cancer Scale (BHBS) in a diverse sample of Black women to provide a measure that captures the sociocultural factors related to perceived breast cancer risk and hair product use. Materials and methods B Feedback @ ncbi.nlm.nih.gov 9:39 834 PMC PubMed Central Q Materials and methods Go to: This study was part of a broader project that used a mixed method design and community- based participatory research (CBPR) principles to evaluate the association between hair prod- ucts use and perceived breast cancer risk among Black women in Southern California. The study was conducted in two phases: a qualitative phase followed by a quantitative phase. Findings from the qualitative phase were used to inform quantitative data collection. This design is par- ticularly useful for developing a new scale [28] The project was conducted by three co-investi- gators one from an academic institution and two from African American community organiza- tions. The original research questions were de- veloped by community stakeholders who were concerned about the growing number of breast cancer diagnoses in their region. To ensure all research activities were within ethical guidelines, an application detailing the project was submitted and approved - Feedback Loma University Institutional Revie AA ncbi.nim.nih.gov C9:39 834 PMC PubMed Central Q project was submitted and approved by the Loma University Institutional Review Board (IRB). Every participant provided written in- formed consent. All individuals involved with data collection were certified (staff and commu- nity research navigators, aka navigators) in re- search ethics using an IRB approved curriculum developed specifically for CBPR data collection [29]. Participants recruitment and procedures Recruitment for the broader study took place in two stages. In stage 1, we used purposive sam- pling to recruit participants (n = 125) who self- identified as African American, African, or Afro-Caribbean. In stage 2, we used snowball and convenience sampling to recruit African American, African, or Afro-Caribbean men (n = 66) and women (n = 211). The social net- works of the two community co-principal inves- tigators agencies were used to recruit partici- pants. For both stages, participants were primar ily recruited face-to-face at churches, hair sa- lons, community meetings, women's confer- ences, hair and education showcases, and other areas where the target population co Also, flyers were posted in these set Feedback ncbi.nim.nih.gov} E PMC PubMed Central Q areas where the target population congregated. Also, flyers were posted in these settings and emailed to listservs of the community investiga- tors. For stage 1, participants received $20 in the form of store cards (e.g. Target; Food 4 Less). Participants were not compensated for their participation in stage 2 of the study. For both stages, data were collected in churches, beauty salons, and community meetings. The analysis described in this paper includes only Black women with or without a history of breast cancer (n = 185). Women were excluded from the study if they did not self-identify as African American, African, or Afro-Caribbean. Source of data and scale measures In Phase 1 of the study, we explored the cultural and personal meaning of hair in the Black com- munity. Interview questions were developed by participant type (i.e., women with and without a history of breast cancer and their male partners, hair stylists, and salon owners) [30]. Questions were piloted, and modified based on partici- pants and community navigator feedback. Inter- views were audiotaped, and field no ' . B Feedback after focus group and key informant @ ncbi.nlm.nih.gov 9:39 834 .. PMC PubMed Central Q views were audiotaped, and field notes drafted after focus group and key informant interviews. Navigators were trained in basic qualitative and quantitative research approaches including the development of semi-structured interview guides, interviewing skills, the codebook devel- opment for qualitative data analysis, and re- search team trainings on how to use QDA-miner -a qualitative data analysis software [31] that was used for data analyses. Navigators held cre- dentials ranging from high school to master's level education. At the time of the study, naviga- tors were part-time employees of the two com- munity organizations of the project. Some navi- gators were retired, while others were full-time doctoral students at local universities. Naviga- tors were also predominantly female, but one male navigator completed the interviews with male participants. Only participants, navigators, and co-principal investigators were present dur- ing data collection. To achieve triangulation, the navigators used a common semi-structured interview guide [32] adjusted to the target audience to conduct key informant interviews and focus grou Feedback groups included women with and w a ncbi.nim.nih.gov9:39 834 PMC PubMed Central Q informant interviews and focus groups. Target groups included women with and without a his- tory of breast cancer, their male partners, hair stylists, and salon owners. While the interviews explored perceptions of the causes of breast cancer, participants' relationship with hair and hair product use, and perceptions of the poten- tial harmfulness of hair care products, the focus groups were used for validation and member checking. Navigators were not blinded to partic- ipants' breast cancer diagnoses. Data were col- lected in 2013 through early 2014. Interviews and focus groups were audio record- ed and transcribed verbatim to maintain accura cy. We used QDA-Miner to code and analyze the transcripts using a Grounded Theory ap- proach [33]. Following open coding, prelimi- nary results were presented to the navigators, discussed with the research team, and organized into related concepts or themes that were used to inform the quantitative instrument develop- ment. The study team engaged in thoughtful deliberations to resolve theme disagreements. Transcripts were not returned to participants for comments and corrections although participant feedback was obtained during the fo The most prominent themes were th Feedback ncbi.nim.nih.gov} E PMC PubMed Central Q feedback was obtained during the focus groups. The most prominent themes were the critical role of hair for Black women; the relevance of the project to the community; and the notion that \"everything causes cancer\9:39 834 PMC PubMed Central Q hairstyles. Items included "Hair has a special role in Black culture"; "My hair is a cultural reflection of who I am"; and "I do not care how much I spend on hair products." For all ques- tions, the Likert scale response options were Strongly disagree, Disagree, Agree, and Strong- ly agree. The 27-item scale discussed here was one component of a larger 42-item survey in- strument. Other questions explored respondent's lifestyle, health behaviors, BC knowledge, de- mographics, and family medical history. Ques- tions were reviewed for clarity among the re- search team and pilot tested prior to their use in the final survey. In Phase 2, navigators used the 42-item ques- tionnaire developed in Phase 1 to collect data in settings previously mentioned. Each question- naire took approximately 30-45 minutes to complete and the majority (approximately 98%) were completed in person. Those that were not completed in person were submitted electroni- cally or via postal mail. Data were collected from 2015 through 2016. Demographic measures Feedback Education level was assessed using a ncbi.nim.nih.govI \\...J Alarm I e i, H PMC PubMed Central Q Education level was assessed using the ques- tion: \"What is the highest level of education you have completed?\"\" Response options were: Some high school, High school diploma (or equiva- lent), Some college, College degree, Graduate degree, and Professional certification (cosme- tology, etc.). Age was denoted in years. House- hold income question was: \"Please check the range of income that is closest to your own:\" with the following response options: Less than $25,000; $26,000-350,000; $51,000-$75,000; $76,000-$100,000; $100,000-$150,000 and More than $151,000. Insurance status was as- sessed using the question: \"Do you have health insurance?\" With response options Yes or No. Birth place was determined using the question: \"Were you born in the United States?\"\" With re- sponse options Yes or No. The question, \"Have you been diagnosed with cancer?\" With re- sponse options Yes or No, was used to assess diagnosis status. Family history of breast cancer was determined using the question: \"Have any of your family members been diagnosed with breast cancer?\" With response options Yes or No. The question \"Have you ever had a mam- mogram?\"' was used to assess partic' . . . Feedback cancer screening history with respor = & ncbi.nlm.nih.gov 9:47 834 ... PMC PubMed Central Q mogram?" was used to assess participant breast cancer screening history with response options Yes or No. Product use information was ob- tained using the question "How often do you use the following products?" Product types in- cluded wash out conditioner, leave in condition- er, relaxer from salon, do it yourself relaxer, de- tangler, damaged hair treatment (i.e. hair may- onnaise), do it yourself hair dye kits, and profes- sional hair coloring. Response options included 1) Several times a week, 2) Daily, 3) Several times a month, 4) Several times a year, 5) Used to/stopped using and 6) Never used it. Response options 1-5 were recategorized as Yes for prod- uct use and response option 6 was recategorized as No for product use in analyses. Principal components analysis In order to examine the underlying structure and dimensions of identity, hair products use, and perceived breast cancer risk, a Principal Com- ponent Analysis (PCA) was conducted using SPSS 24.0 [34]. As this is the first analysis of its kind to examine the cultural influence of hair product use among Black women, soul mad el-fitting techniques were tested, inc Feedback ncbi.nim.nih.gov9:47 834 PMC PubMed Central Q product use among Black women, several mod- el-fitting techniques were tested, including both orthogonal and oblique rotations. An oblique rotation (e.g. Promax) allows components to be intercorrelated, while an orthogonal rotation (e.g. Varimax) minimizes the number of vari- ables with high loadings and simplifies the solu- tion [35]. As a significant dearth of similar vali- dation studies exists in the literature-and thus no factor analytic studies with which to compare -we examined several exploratory models dur- ing this first analysis phase, including both Pro- max and Varimax rotations. Several criteria were used to examine the num- ber and combination of items in each compo- nent, including Horn's parallel analysis [36], a scree plot of Eigenvalues[37], Kaiser criterion [38], and factor loadings[39]. The crite- rion cutoff was set at +0.35 for the item load- ings. Based on this criterion, each item loaded most highly on one of two distinct components, with many items loading poorly (0.90, and Tuck- er Lewis Index (TLI) of >.90 [43-45]. The x2 assess overall fit and the discrepancy between the sample and fitted covariance matrices. In addition to the x- test, the AIC is compared for each fitted model[46]. The AIC is a widely used index of fit, such that smaller AIC values are indicative of the most parsimonious Feedback fitting model. a ncbi.nim.nih.gov9:47 834 .. PMC PubMed Central Q index of fit, such that smaller AIC values are indicative of the most parsimonious and well- fitting model. Demographic The final analytic sample (n = 185) was com- prised of 73% African American and 27% Car- ibbean and African Black women aged 29 to 64 years (Table 1). Participants were highly educat- ed with over 50% of participants having a col- lege or a more advanced degree. In addition, most participants reported use of hair products. Overall, participants reported using wash out conditioner (89.7%), leave in conditioner (83.8%), relaxer (70.8%), do it yourself relaxer (58.4%), detangler (63.2%), treatment for dam- aged hair(64.3), do it yourself hair dye kits(50.8%), and professional hair color- ing(55.1%). Table 1 Demographic characteristics of participants (N = 185). Demographics African Caribbeanedback a ncbi.nim.nih.gov9:47 834 PMC PubMed Central Q Table 1 Demographic characteristics of participants (N = 185). Demographics African Caribbean/African American n = 50 (27.0%) n = 135 (73.0%) Education level > Some 9(6.7) 3(6.4) high school $75,000 Insurance status Yes 127(96.2) 47(94.0) No 5(3.8) 3(6.0) Birth place Feedback US 121(91.7) 316 a ncbi.nim.nih.gov9:48 834 .. PMC PubMed Central Q Birth place US 121(91.7) 9(18.4) Non-US 11(8.3) 40(81.6) Breast cancer screening Yes 55(64.7) 19(57.6) No 30(35.3) 14(42.4%) Breast cancer diagnosis Yes 12(9.1) 3(6.1) No 120(90.9) 46(93.9) Family history of breast cancer Yes 58(45.3) 9(18.8) No 70(54.7) 39(81.3) Open in a separate window Percentages and number of participants do not equal total due to missing data. PCA and CFA Feedback 1 41. a ncbi.nim.nih.gov9:48 834 PMC PubMed Central Q PCA and CFA We examined the factor structure of the 27 items with an aim to better understand the struc ture and dimensionality of identity, perceived risk, and attitude regarding Black hair and per- ceived breast cancer risk. According to fit crite- ria, PCA with Varimax rotation yielded two dis- tinct components that accounted for 61% of the total variance, with 11 of the 27 items loading highly on these two unique components. A par- allel analysis also indicated a two-component solution, though 1-component and 3-component solutions were also examined in subsequent CFA[36]. The remaining 16 items were dropped due to poor fit (

9:36 834 .. PMC PubMed Central Q The Black identity, hair product use, and breast cancer scale Dede Teteh, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, #1,* Marissa Ericson, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, #2 Sabine Monice, Writing - original draft, 3, Lenna Dawkins-Moultin, Conceptualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, #1 Nasim Bahadorani, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, 4. Phyllis Clark, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Writing - review & editing, + Eudora Mitchell, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Writing - review & editing, , Lindsey S. Trevino, Writing - review & editing, 1. Adana Llanos, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, " Rick Kittles, Writing - review & editing, " and Susanne Montgomery, Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing - review & editing#3 Cheng-Shi Shiu, Editor Feedback a ncbi.nim.nih.gov9:36 834 ... PMC PubMed Central Q Abstract Go to: Introduction Across the African Diaspora, hair is synony mous with identity. As such, Black women use a variety of hair products, which often contain more endocrine-disrupting chemicals than prod- ucts used by women of other races. An emerg- ing body of research is linking chemicals in hair products to breast cancer, but there is no validat- ed instrument that measures constructs related to hair, identity, and breast health. The objective of this study was to develop and validate the Black Identity, Hair Product Use, and Breast Cancer Scale (BHBS) in a diverse sample of Black women to measure the social and cultural constructs associated with Black women's hair product use and perceived breast cancer risk. Methods Participants completed a 27-item scale that queried perceptions of identity, hair products, and breast cancer risk. Principal Component Analyses (PCA) were conducted to establish the underlying component structures, ar Feedback tom fontor analunia (CDA ) runn wand a ncbi.nim.nih.gov9:36 834 .. PMC PubMed Central Q underlying component structures, and confirma- tory factor analysis (CFA) was used to deter- mine model fit. Results Participants (n = 185) were African American (73%), African, and Caribbean Black women (27%) aged 29 to 64. PCA yielded two compo- nents that accounted for 61% of total variance. Five items measuring sociocultural perspec- tives about hair and identity loaded on subscale 1 and accounted for 32% of total variance (a = 0.82; 95% CI = 0.77-0.86). Six items assessing perceived breast cancer risk related to hair product use loaded on subscale 2 and accounted for 29% of total variance (a = 0.82 (95% CI = 0.74-0.86). CFA confirmed the two-component structure (Root Mean Square Error of Approxi- mation = 0.03; Comparative Fit Index = 0.91; Tucker Lewis Index = 0.88). Conclusions The BHBS is a valid measure of social and cul- tural constructs associated with Black women's hair product use and perceived brea Feedback a ncbi.nim.nih.gov} PMC PubMed Central Q hair product use and perceived breast cancer risk. This scale is useful for studies that assess cultural norms in the context of breast cancer risk for Black women. Introduction Go to: Breast cancer remains the second leading cause of death in the United States among women [1, 2], with Black women being particularly vulner- able [3]. Recent reports indicate that while the incidence rates of breast cancer in Black and White women have converged [4], mortality rates among Black women are at least 40% higher than their White counterparts [3]. Fur- thermore, Black women are more likely to be diagnosed with and die from more aggressive forms of breast cancer than White women who are more often diagnosed at earlier stages [3]. Research on cancer disparities has not been able to conclusively explain Black women's elevated risk of breast cancer mortality or their more ag- gressive phenotypes, but differences in progno- sis and etiology have been correlated with race [6], genetics [7], lifestyle and behavioral factors [8], and environmental exposures [9]. B Feedback One environmental factor that has b @ ncbi.nlm.nih.gov 9:37 834 PMC PubMed Central Q increasing attention in breast cancer research is hair and personal care products [2-11]. A grow- ing body of literature [2-14] supports an associ- ation between use of some hair care products (e.g., hair dyes, relaxers, and deep conditioners) and breast cancer risk. Data from animal models [15-17] suggest exposures to compounds found in some hair products, particularly those con- taining endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDC's) and chemicals with mutagenic properties, may be important etiologic risk factors for several human cancers, including breast cancer. Stiel and colleagues' review of hair product use and breast cancer risk included research on environ- mental estrogen, EDCs, and placenta-derived ingredients found in hair products used primaria ly by African American women. The authors concluded there is significant evidence to sup- port the role of hair product use in the risk of early-onset breast cancer in Black women. In addition, Myers et al. [14] assessed ethanol extracts of eight personal care products fre- quently used by African Americans Feedback genic and anti-estrogenic activity in AA ncbi.nim.nih.gov C9:37 834 PMC PubMed Central Q quently used by African Americans for estro- genic and anti-estrogenic activity in a human breast cancer cell line. They detected estrogenic activity in oil, hair lotion, extra-dry skin lotion, intensive skin lotion, and petroleum jelly, and anti-estrogenic activity in placenta hair condi- tioner, tea-tree hair conditioner, and cocoa but- ter skin cream. The authors concluded some hair and skin care products have ingredients that can mimic estrogen functioning. Llanos and colleagues [11] also examined the association between breast cancer risk and use of hair dye, chemical relaxers, and deep conditioners in a sample of African American and White women. They found, among the dark hair dye shades, African American use was associated with in- creased breast cancer risk (OR = 1.51, 95% CI: 1.20-1.90). Despite the mounting evidence of possible health risk, hair products remain popular in the Black community [10, 11, 18]. Compared to white women, Black women invest more money on hair products [19], are more likely to use re- laxers and deep conditioners, and use them at younger ages [11, 18]. As a result, Black Women are more likely to be exposed to haw monally active chemicals in hair prc Feedback a ncbi.nim.nih.gov} PMC PubMed Central Q women are more likely to be exposed to hor- monally active chemicals in hair products across their lifespan, potentially increasing their risk for developing breast cancer [18]. The literature on Black women's attitude to their hair offers mixed explanations for the popularity of hair care products in Black communities. Some scholars suggest hair across the African diaspora is synonymous with identity, individu- ality, and beauty norms [20, 21]. For many Black women, maintaining hair with sculpting and straightening products is an extension of self and a way to achieve social acceptance [21, 22]. Alternatively, scholars such as Johnson and Bankhead challenge the notion that straight hair represents an ideal form of beauty and is con- nected to social acceptance [22]. They argue that wearing hair in its natural state is the \"new normal\" that celebrates Black identity and pride. But even products designed for natural Black hair have been found to contain potential- ly harmful ingredients [23]. So, whether Black women choose to chemically alter their hair or keep it in its natural state, they are overexposed to hair products containing endocrine disrupting and other toxic chemicalsmany of " "~ not listed on product labels as they I @ ncbi.nlm.nih.gov } PMC PubMed Central Q not listed on product labels as they are usually listed generically as fragrances [10, 24]. There is a gap in our understanding of how these environmental, sociocultural, and biologi- cal factors converge and impact breast cancer risk and outcomes among Black women. Cur- rently, there 1s no validated scale that measures constructs related to hair, identity, and breast health. Instruments have been developed to measure related but general issues, such as so- cial and personal identity [25], health beliefs [26], and perceptions of health risks [27]. How- ever, none of these instruments capture the con- structs that emerge at the intersection of social, cultural, and health-related factors. Having a validated tool that measure these latent struc- tures will provide a more comprehensive under- standing of Black women's breast cancer risk. The purpose of this study was to validate the Black Identity, Hair Product Use, and Breast Cancer Scale (BHBS) in a diverse sample of Black women to provide a measure that captures the sociocultural factors related to perceived breast cancer risk and hair product use. Materials and methods B Feedback @ ncbi.nlm.nih.gov 9:39 834 PMC PubMed Central Q Materials and methods Go to: This study was part of a broader project that used a mixed method design and community- based participatory research (CBPR) principles to evaluate the association between hair prod- ucts use and perceived breast cancer risk among Black women in Southern California. The study was conducted in two phases: a qualitative phase followed by a quantitative phase. Findings from the qualitative phase were used to inform quantitative data collection. This design is par- ticularly useful for developing a new scale [28] The project was conducted by three co-investi- gators one from an academic institution and two from African American community organiza- tions. The original research questions were de- veloped by community stakeholders who were concerned about the growing number of breast cancer diagnoses in their region. To ensure all research activities were within ethical guidelines, an application detailing the project was submitted and approved - Feedback Loma University Institutional Revie AA ncbi.nim.nih.gov C9:39 834 PMC PubMed Central Q project was submitted and approved by the Loma University Institutional Review Board (IRB). Every participant provided written in- formed consent. All individuals involved with data collection were certified (staff and commu- nity research navigators, aka navigators) in re- search ethics using an IRB approved curriculum developed specifically for CBPR data collection [29]. Participants recruitment and procedures Recruitment for the broader study took place in two stages. In stage 1, we used purposive sam- pling to recruit participants (n = 125) who self- identified as African American, African, or Afro-Caribbean. In stage 2, we used snowball and convenience sampling to recruit African American, African, or Afro-Caribbean men (n = 66) and women (n = 211). The social net- works of the two community co-principal inves- tigators agencies were used to recruit partici- pants. For both stages, participants were primar ily recruited face-to-face at churches, hair sa- lons, community meetings, women's confer- ences, hair and education showcases, and other areas where the target population co Also, flyers were posted in these set Feedback ncbi.nim.nih.gov} E PMC PubMed Central Q areas where the target population congregated. Also, flyers were posted in these settings and emailed to listservs of the community investiga- tors. For stage 1, participants received $20 in the form of store cards (e.g. Target; Food 4 Less). Participants were not compensated for their participation in stage 2 of the study. For both stages, data were collected in churches, beauty salons, and community meetings. The analysis described in this paper includes only Black women with or without a history of breast cancer (n = 185). Women were excluded from the study if they did not self-identify as African American, African, or Afro-Caribbean. Source of data and scale measures In Phase 1 of the study, we explored the cultural and personal meaning of hair in the Black com- munity. Interview questions were developed by participant type (i.e., women with and without a history of breast cancer and their male partners, hair stylists, and salon owners) [30]. Questions were piloted, and modified based on partici- pants and community navigator feedback. Inter- views were audiotaped, and field no ' . B Feedback after focus group and key informant @ ncbi.nlm.nih.gov 9:39 834 .. PMC PubMed Central Q views were audiotaped, and field notes drafted after focus group and key informant interviews. Navigators were trained in basic qualitative and quantitative research approaches including the development of semi-structured interview guides, interviewing skills, the codebook devel- opment for qualitative data analysis, and re- search team trainings on how to use QDA-miner -a qualitative data analysis software [31] that was used for data analyses. Navigators held cre- dentials ranging from high school to master's level education. At the time of the study, naviga- tors were part-time employees of the two com- munity organizations of the project. Some navi- gators were retired, while others were full-time doctoral students at local universities. Naviga- tors were also predominantly female, but one male navigator completed the interviews with male participants. Only participants, navigators, and co-principal investigators were present dur- ing data collection. To achieve triangulation, the navigators used a common semi-structured interview guide [32] adjusted to the target audience to conduct key informant interviews and focus grou Feedback groups included women with and w a ncbi.nim.nih.gov9:39 834 PMC PubMed Central Q informant interviews and focus groups. Target groups included women with and without a his- tory of breast cancer, their male partners, hair stylists, and salon owners. While the interviews explored perceptions of the causes of breast cancer, participants' relationship with hair and hair product use, and perceptions of the poten- tial harmfulness of hair care products, the focus groups were used for validation and member checking. Navigators were not blinded to partic- ipants' breast cancer diagnoses. Data were col- lected in 2013 through early 2014. Interviews and focus groups were audio record- ed and transcribed verbatim to maintain accura cy. We used QDA-Miner to code and analyze the transcripts using a Grounded Theory ap- proach [33]. Following open coding, prelimi- nary results were presented to the navigators, discussed with the research team, and organized into related concepts or themes that were used to inform the quantitative instrument develop- ment. The study team engaged in thoughtful deliberations to resolve theme disagreements. Transcripts were not returned to participants for comments and corrections although participant feedback was obtained during the fo The most prominent themes were th Feedback ncbi.nim.nih.gov} E PMC PubMed Central Q feedback was obtained during the focus groups. The most prominent themes were the critical role of hair for Black women; the relevance of the project to the community; and the notion that \"everything causes cancer\9:39 834 PMC PubMed Central Q hairstyles. Items included "Hair has a special role in Black culture"; "My hair is a cultural reflection of who I am"; and "I do not care how much I spend on hair products." For all ques- tions, the Likert scale response options were Strongly disagree, Disagree, Agree, and Strong- ly agree. The 27-item scale discussed here was one component of a larger 42-item survey in- strument. Other questions explored respondent's lifestyle, health behaviors, BC knowledge, de- mographics, and family medical history. Ques- tions were reviewed for clarity among the re- search team and pilot tested prior to their use in the final survey. In Phase 2, navigators used the 42-item ques- tionnaire developed in Phase 1 to collect data in settings previously mentioned. Each question- naire took approximately 30-45 minutes to complete and the majority (approximately 98%) were completed in person. Those that were not completed in person were submitted electroni- cally or via postal mail. Data were collected from 2015 through 2016. Demographic measures Feedback Education level was assessed using a ncbi.nim.nih.govI \\...J Alarm I e i, H PMC PubMed Central Q Education level was assessed using the ques- tion: \"What is the highest level of education you have completed?\"\" Response options were: Some high school, High school diploma (or equiva- lent), Some college, College degree, Graduate degree, and Professional certification (cosme- tology, etc.). Age was denoted in years. House- hold income question was: \"Please check the range of income that is closest to your own:\" with the following response options: Less than $25,000; $26,000-350,000; $51,000-$75,000; $76,000-$100,000; $100,000-$150,000 and More than $151,000. Insurance status was as- sessed using the question: \"Do you have health insurance?\" With response options Yes or No. Birth place was determined using the question: \"Were you born in the United States?\"\" With re- sponse options Yes or No. The question, \"Have you been diagnosed with cancer?\" With re- sponse options Yes or No, was used to assess diagnosis status. Family history of breast cancer was determined using the question: \"Have any of your family members been diagnosed with breast cancer?\" With response options Yes or No. The question \"Have you ever had a mam- mogram?\"' was used to assess partic' . . . Feedback cancer screening history with respor = & ncbi.nlm.nih.gov 9:47 834 ... PMC PubMed Central Q mogram?" was used to assess participant breast cancer screening history with response options Yes or No. Product use information was ob- tained using the question "How often do you use the following products?" Product types in- cluded wash out conditioner, leave in condition- er, relaxer from salon, do it yourself relaxer, de- tangler, damaged hair treatment (i.e. hair may- onnaise), do it yourself hair dye kits, and profes- sional hair coloring. Response options included 1) Several times a week, 2) Daily, 3) Several times a month, 4) Several times a year, 5) Used to/stopped using and 6) Never used it. Response options 1-5 were recategorized as Yes for prod- uct use and response option 6 was recategorized as No for product use in analyses. Principal components analysis In order to examine the underlying structure and dimensions of identity, hair products use, and perceived breast cancer risk, a Principal Com- ponent Analysis (PCA) was conducted using SPSS 24.0 [34]. As this is the first analysis of its kind to examine the cultural influence of hair product use among Black women, soul mad el-fitting techniques were tested, inc Feedback ncbi.nim.nih.gov9:47 834 PMC PubMed Central Q product use among Black women, several mod- el-fitting techniques were tested, including both orthogonal and oblique rotations. An oblique rotation (e.g. Promax) allows components to be intercorrelated, while an orthogonal rotation (e.g. Varimax) minimizes the number of vari- ables with high loadings and simplifies the solu- tion [35]. As a significant dearth of similar vali- dation studies exists in the literature-and thus no factor analytic studies with which to compare -we examined several exploratory models dur- ing this first analysis phase, including both Pro- max and Varimax rotations. Several criteria were used to examine the num- ber and combination of items in each compo- nent, including Horn's parallel analysis [36], a scree plot of Eigenvalues[37], Kaiser criterion [38], and factor loadings[39]. The crite- rion cutoff was set at +0.35 for the item load- ings. Based on this criterion, each item loaded most highly on one of two distinct components, with many items loading poorly (0.90, and Tuck- er Lewis Index (TLI) of >.90 [43-45]. The x2 assess overall fit and the discrepancy between the sample and fitted covariance matrices. In addition to the x- test, the AIC is compared for each fitted model[46]. The AIC is a widely used index of fit, such that smaller AIC values are indicative of the most parsimonious Feedback fitting model. a ncbi.nim.nih.gov9:47 834 .. PMC PubMed Central Q index of fit, such that smaller AIC values are indicative of the most parsimonious and well- fitting model. Demographic The final analytic sample (n = 185) was com- prised of 73% African American and 27% Car- ibbean and African Black women aged 29 to 64 years (Table 1). Participants were highly educat- ed with over 50% of participants having a col- lege or a more advanced degree. In addition, most participants reported use of hair products. Overall, participants reported using wash out conditioner (89.7%), leave in conditioner (83.8%), relaxer (70.8%), do it yourself relaxer (58.4%), detangler (63.2%), treatment for dam- aged hair(64.3), do it yourself hair dye kits(50.8%), and professional hair color- ing(55.1%). Table 1 Demographic characteristics of participants (N = 185). Demographics African Caribbeanedback a ncbi.nim.nih.gov9:47 834 PMC PubMed Central Q Table 1 Demographic characteristics of participants (N = 185). Demographics African Caribbean/African American n = 50 (27.0%) n = 135 (73.0%) Education level > Some 9(6.7) 3(6.4) high school $75,000 Insurance status Yes 127(96.2) 47(94.0) No 5(3.8) 3(6.0) Birth place Feedback US 121(91.7) 316 a ncbi.nim.nih.gov9:48 834 .. PMC PubMed Central Q Birth place US 121(91.7) 9(18.4) Non-US 11(8.3) 40(81.6) Breast cancer screening Yes 55(64.7) 19(57.6) No 30(35.3) 14(42.4%) Breast cancer diagnosis Yes 12(9.1) 3(6.1) No 120(90.9) 46(93.9) Family history of breast cancer Yes 58(45.3) 9(18.8) No 70(54.7) 39(81.3) Open in a separate window Percentages and number of participants do not equal total due to missing data. PCA and CFA Feedback 1 41. a ncbi.nim.nih.gov9:48 834 PMC PubMed Central Q PCA and CFA We examined the factor structure of the 27 items with an aim to better understand the struc ture and dimensionality of identity, perceived risk, and attitude regarding Black hair and per- ceived breast cancer risk. According to fit crite- ria, PCA with Varimax rotation yielded two dis- tinct components that accounted for 61% of the total variance, with 11 of the 27 items loading highly on these two unique components. A par- allel analysis also indicated a two-component solution, though 1-component and 3-component solutions were also examined in subsequent CFA[36]. The remaining 16 items were dropped due to poor fit ( Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts