Question: This assignment asks you to complete the case analysis on Burt's Bees from the text (see case at end of chapter 5). Burt's Bees is

This assignment asks you to complete the case analysis on "Burt's Bees" from the text (see case at end of chapter 5). Burt's Bees is an interesting Case Analysis, and one that most people can relate to, as their products are found almost everywhere we routinely shop, either at the local grocery or drug store, or at health food and other specialty stores - not to mention the large, conglomerate stores like Wal-Mart and Target. Burt's Bees' products are immensely popular; however, if you are unfamiliar with the products or the company behind them, you can learn more about both at the company's website: www.burtsbees.com/.

Before you prepare your case analysis, first watch this short video on this interesting individual and business:

Roxanne Quimby video-Burt's Bees Wax [4 mins]

In preparing a case, it is recommended that your first reading/viewing be a relatively quick one. Read the case and watch the video once, and make some notes: Who and what are involved here? What seems to be the major questions or issues?

Then, take a second and more thorough reading of the case, testing your preliminary conclusions from the first reading concerning the major problems and key players.

Next, begin shifting through the facts in the case and sorting them out in terms that are useful to you in analyzing and resolving the major issues. Keep in mind that case facts are presented in a more orderly fashion than they tend to be in the real world, but you should not assume that they are all equally useful, or that they are properly and fully related as presented in the case.

Finally, write a clear, concise, and thorough report of your analysis and recommendations. Each case analysis is a minimum of five pages in length and professional in appearance

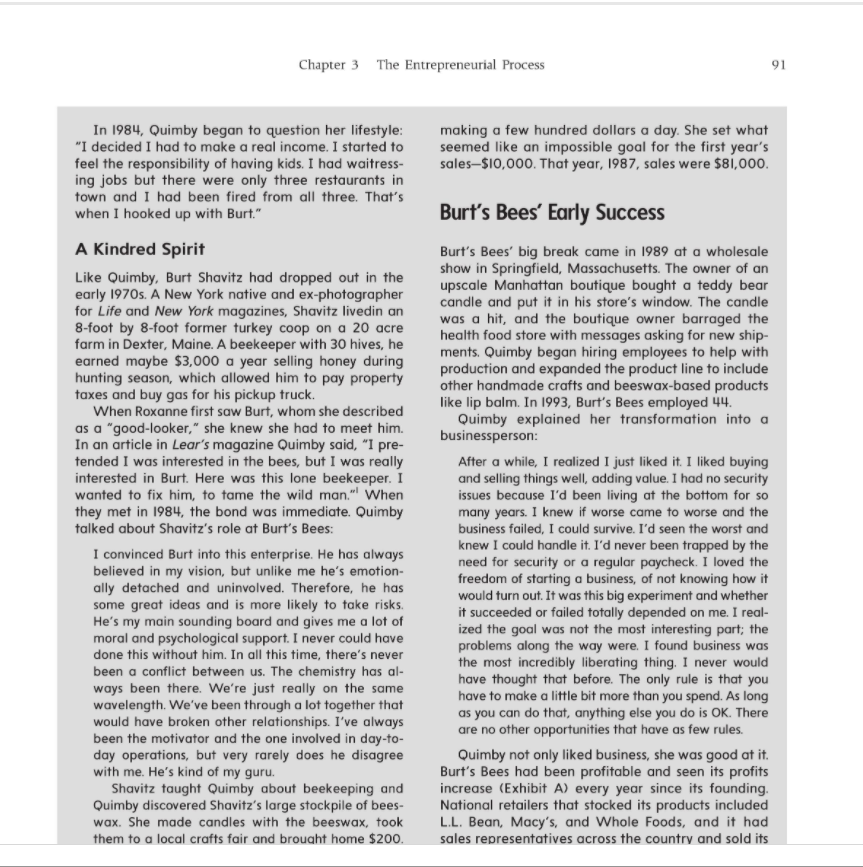

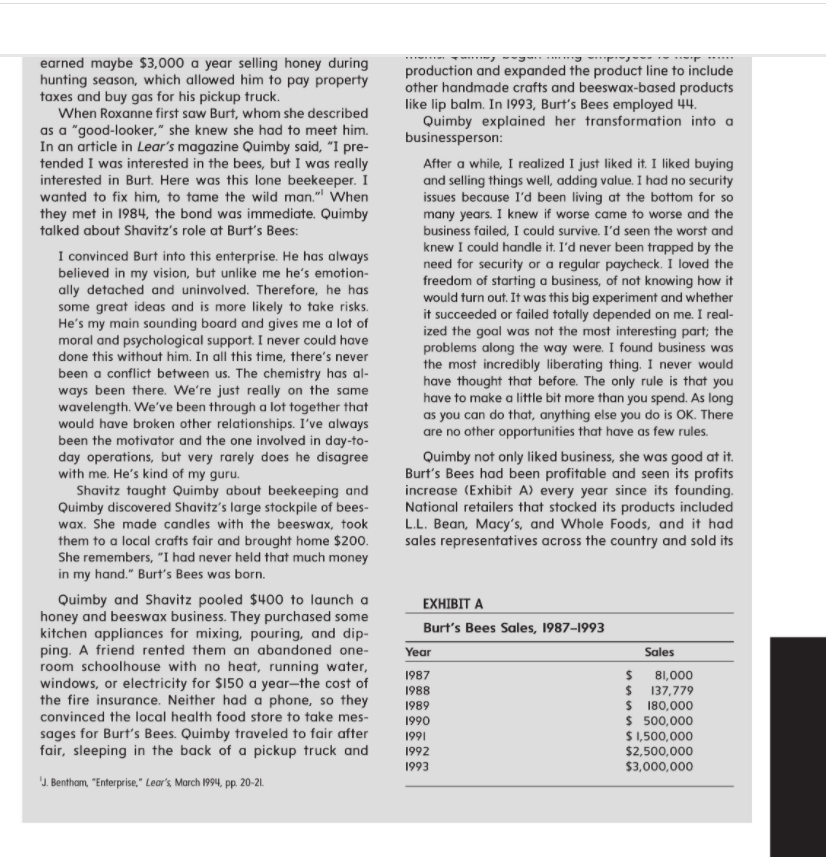

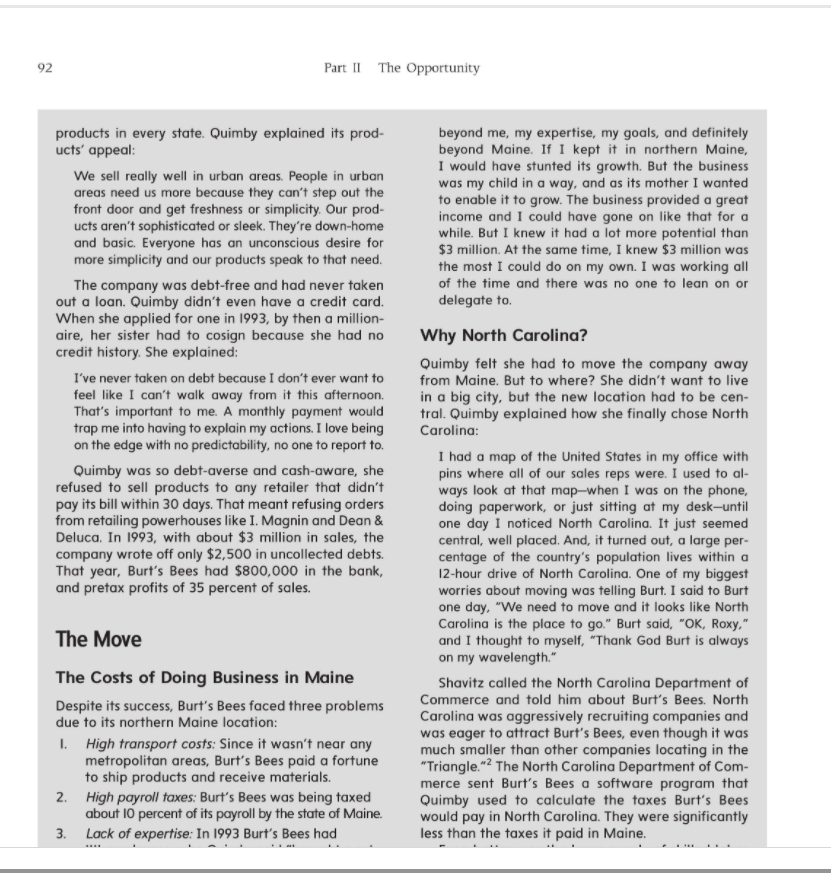

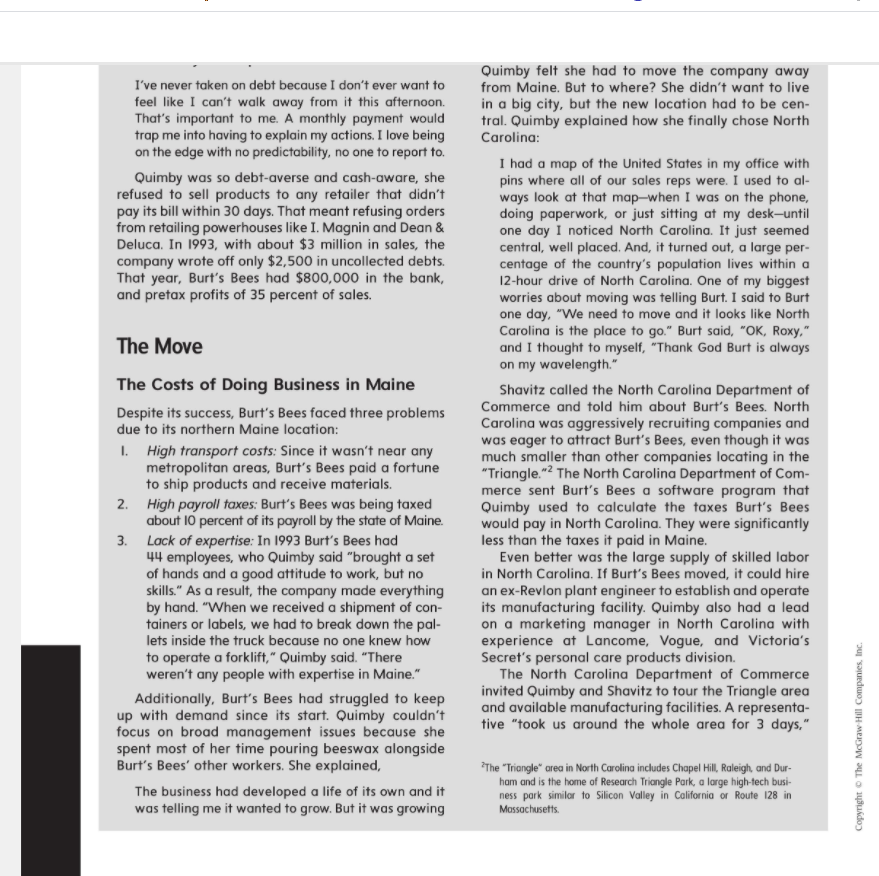

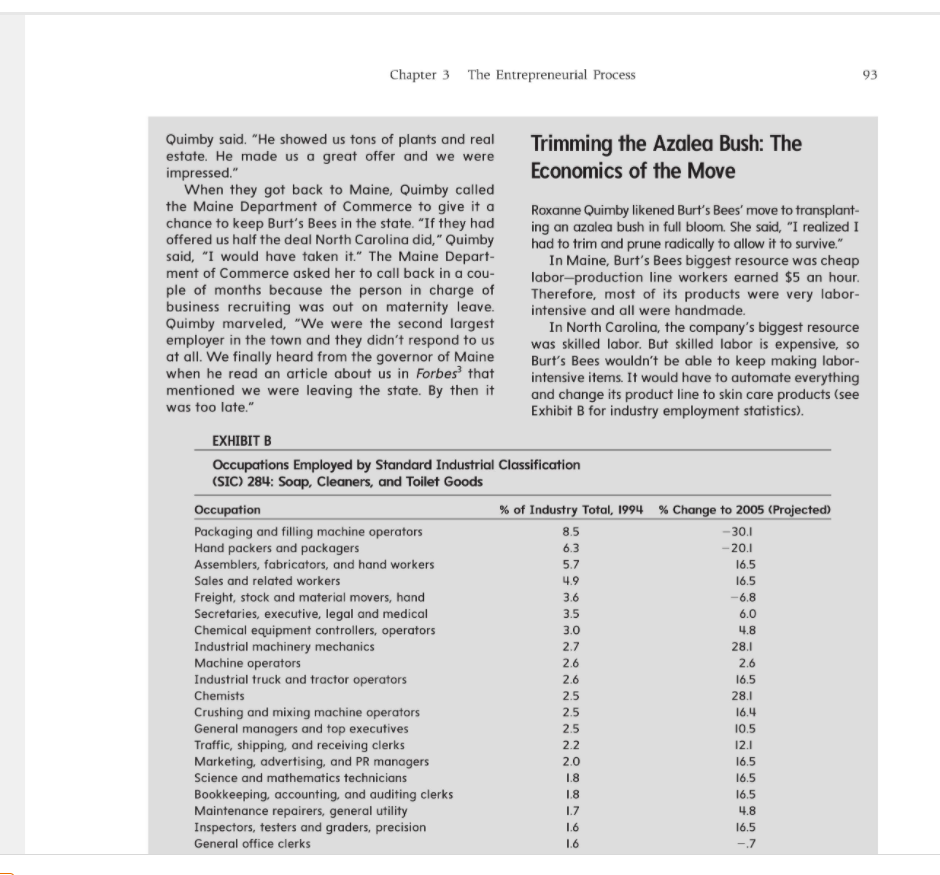

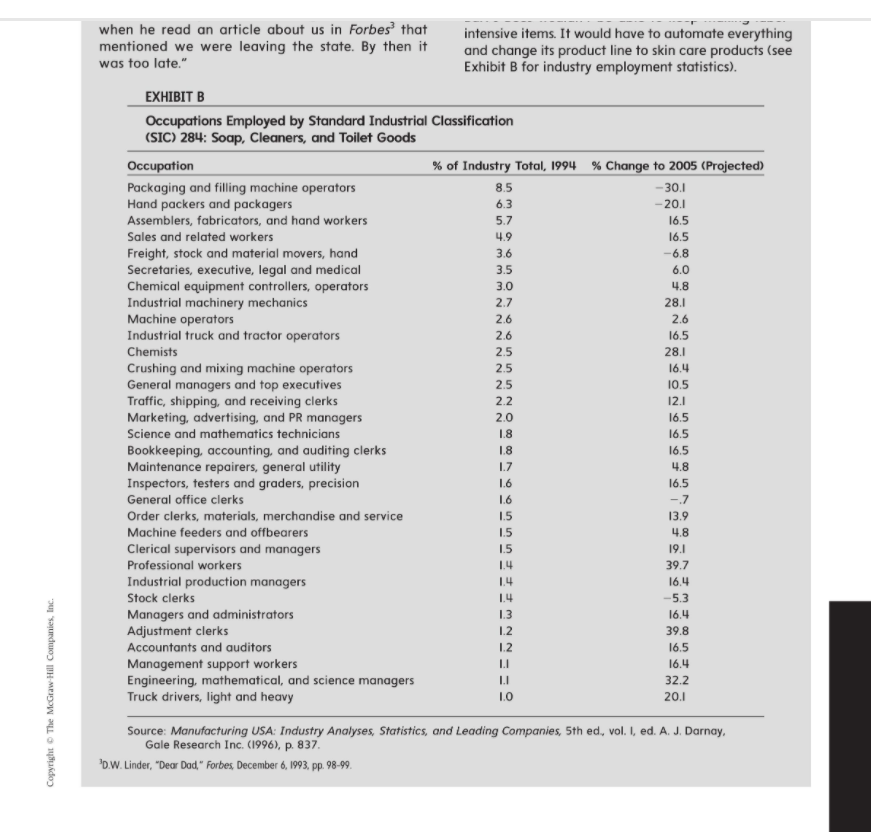

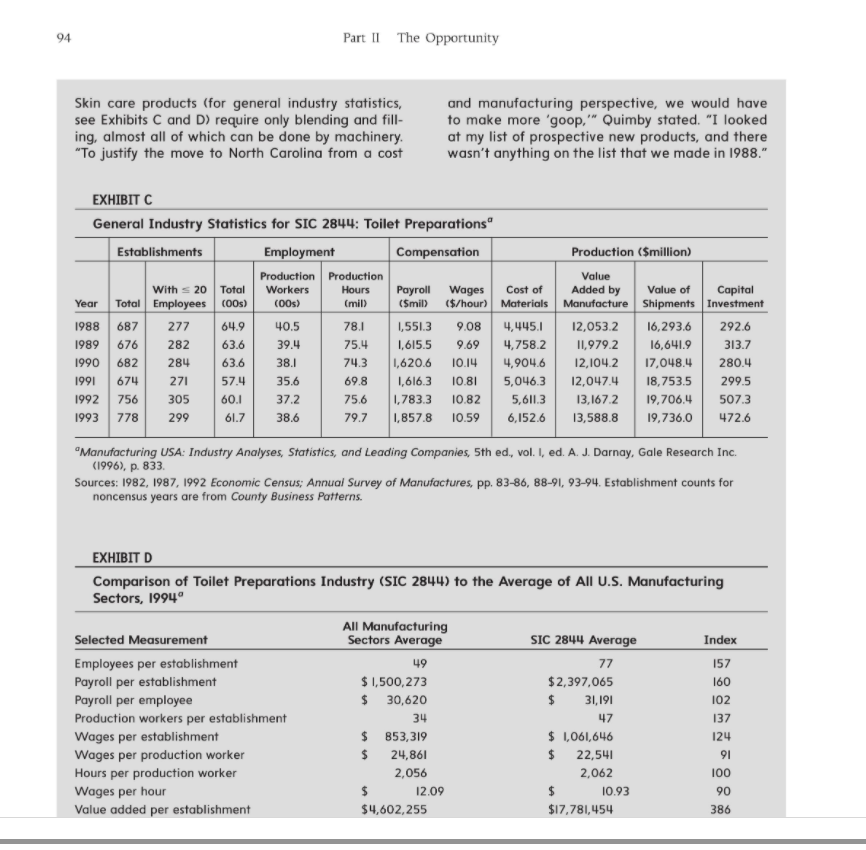

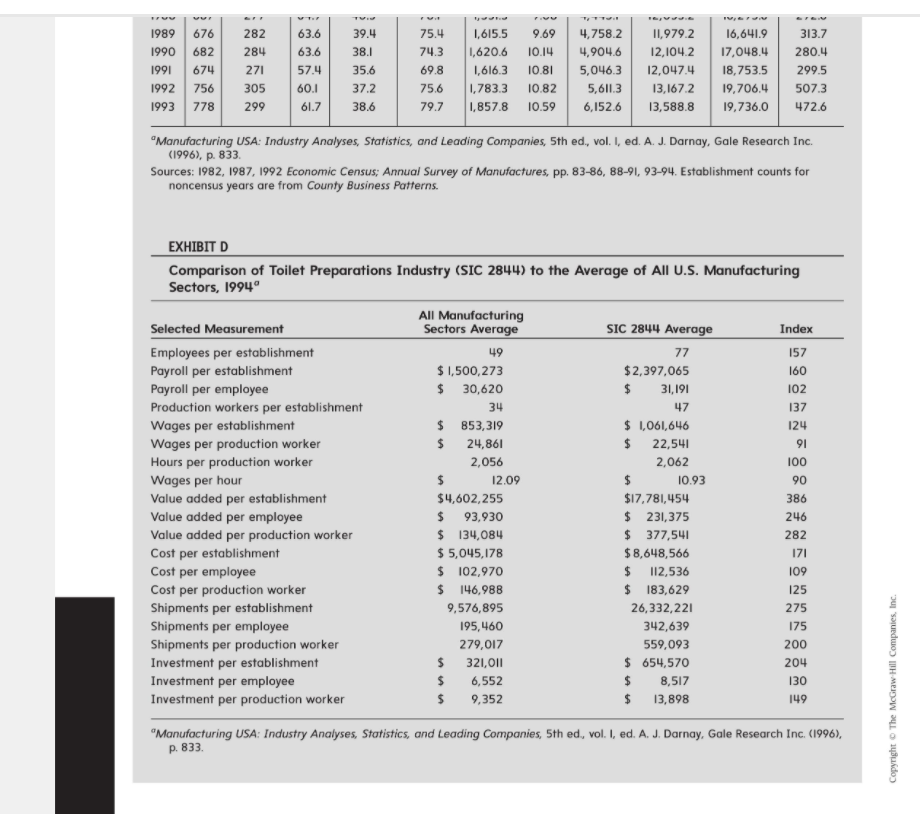

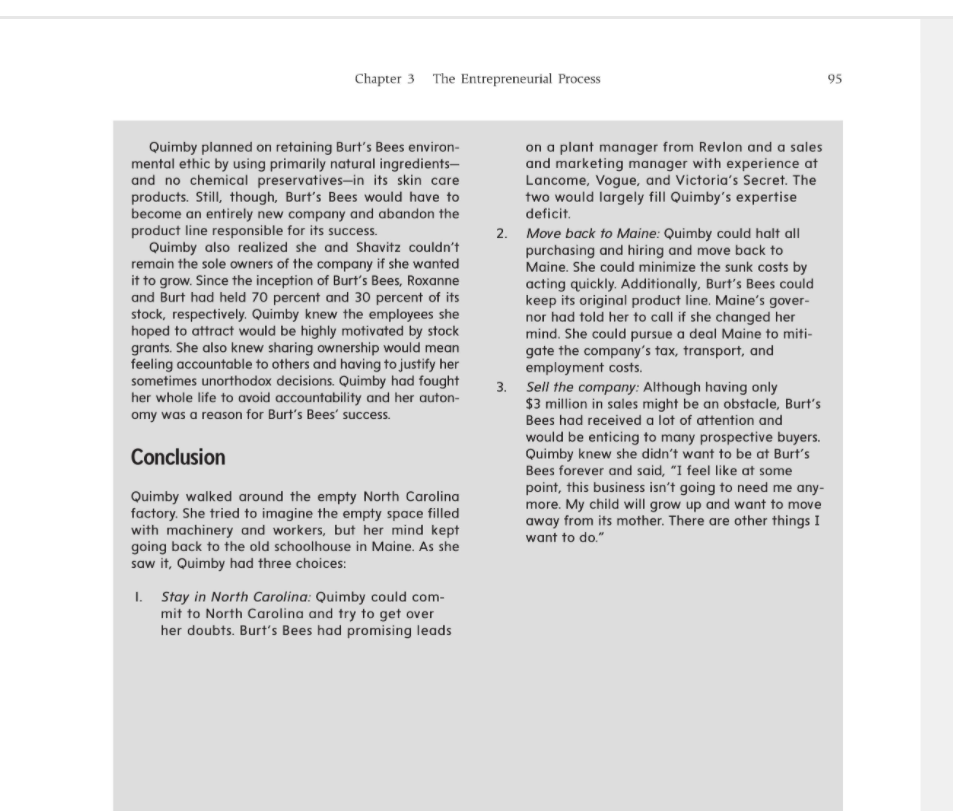

Part I Opportunity Case Roxanne Quimby Preparation Questions 1. Who can be an entrepreneur? 2. What are the risks, rewards, and trade-offs of a lifestyle business versus a high-potential business-one that will exceed $5 million in sales and grow substantially? 3. What is the difference between an idea and an opportunity? For whom? What can be learned from Exhibits C and D? 4. Why has the company succeeded so far? 5. What should Roxanne and Burt do, and why? Our goal for the first year was $10,000 in total sales. I figured if I could take home half of that, it would be more money than I'd ever seen. Roxanne Quimby Roxanne Quimby The Black Sheep "I was a real black sheep in my family," Quimby said. One sister worked for AMEX, another worked for Charles Schwab, and her father worked for Merrill Lynch, but she was not interested in business. Quimby attended the San Francisco Art Institute in the late 1960s and "got radicalized out there," she explained. "I studied, oil painted, and graduated without any job prospects. I basically dropped out of life. I moved to central Maine where land was really cheap-$100 an acreand I could live removed from society." While Quimby was in college, her father discov- ered she was living with her boyfriend and disowned her. Her father, a Harvard Business School graduate and failed entrepreneur, did give her one gift-an early entrepreneurial education. At the age of five, he told her he wouldn't give her a cent for college but would match every dollar she earned herself. By her high school graduation Quimby had banked $5,000 by working on her father's entrepreneurial projects and selling handmade crafts. In 1975, Quimby and her boyfriend married and moved to Guilford, Maine-an hour northwest of Bangor. They bought 30 acres at $100 an acre and built a two room house with no electricity, running water, or phone. In 1977, Quimby had twins, and her lifestyle became a burden. She washed diapers in pots of boiling water on a wood-burning stove and struggled to make ends meet with minimum wage jobs. Her marriage broke apart when the twins were four. Quimby put her belongings on a toboggan and pulled it across the snow to a friend's house. The money-making skills her father forced her to develop allowed Quimby to survive. She and her chil- dren lived in a small tent. and Quimby made almost Introduction Roxanne Quimby sat in the president's office of Burt's Bees' newly relocated manufacturing facility in Raleigh, North Carolina. She missed Maine, the company's previous home. Quimby had founded and built Burt's Bees, a manufacturer of beeswax-based personal care products and handmade crafts, in central Maine and wondered if she should move it back there. She explained, When we got to North Carolina, we were totally alone. I realized how much of the business existed in the minds of the Maine employees. There, everyone had their mark on the process. That was all lost when we left Maine in 1994. I just kept thinking, "Why did I move Burt's Bees?" ThanaTMALNdmintha na MDARUL AMALIA 4. Why has the company succeeded so far? 5. What should Roxanne and Burt do, and why? Our goal for the first year was $10,000 in total sales. I figured if I could take home half of that, it would be more money than I'd ever seen. Roxanne Quimby Introduction Roxanne Quimby sat in the president's office of Burt's Bees' newly relocated manufacturing facility in Raleigh, North Carolina. She missed Maine, the company's previous home. Quimby had founded and built Burt's Bees, a manufacturer of beeswax-based personal care products and handmade crafts, in central Maine and wondered if she should move it back there. She explained, When we got to North Carolina, we were totally alone. I realized how much of the business existed in the minds of the Maine employees. There, everyone had their mark on the process. That was all lost when we left Maine in 1994. I just kept thinking, "Why did I move Burt's Bees?" I thought I would pick the company up and move it and everything would be the same. Nothing was the same except that I was still working 20-hour days Quimby needed to make a decision quickly because Burt's Bees was hiring employees and purchasing equipment. If she pulled out now, she could minimize her losses and rehire the 44 employ- ees she had left back in Maine, since none had new jobs yet. On the other hand, she couldn't ignore the reasons she had decided to leave Maine. In Maine, Burt's Bees would probably never grow over $3 million in sales, and Quimby felt it had potential for much more. ME TUE 1Y0U unu yur TuICIILEU vul mere, se explained. "I studied, oil painted, and graduated without any job prospects. I basically dropped out of life. I moved to central Maine where land was really cheap-$100 an acreand I could live removed from society." While Quimby was in college, her father discov- ered she was living with her boyfriend and disowned her. Her father, a Harvard Business School graduate and failed entrepreneur, did give her one gift-an early entrepreneurial education. At the age of five, he told her he wouldn't give her a cent for college but would match every dollar she earned herself. By her high school graduation Quimby had banked $5,000 by working on her father's entrepreneurial projects and selling handmade crafts. In 1975, Quimby and her boyfriend married and moved to Guilford, Maine-an hour northwest of Bangor. They bought 30 acres at $100 an acre and built a two room house with no electricity, running water, or phone. In 1977, Quimby had twins, and her lifestyle became a burden. She washed diapers in pots of boiling water on a wood-burning stove and struggled to make ends meet with minimum wage jobs. Her marriage broke apart when the twins were four. Quimby put her belongings on a toboggan and pulled it across the snow to a friend's house. The money-making skills her father forced her to develop allowed Quimby to survive. She and her chil- dren lived in a small tent, and Quimby made almost $150 a week by working local flea markets, buying low and selling high. She also held jobs waitressing. Quimby said, "I always felt I had an entrepreneurial spirit. Even as a waitress I felt entrepreneurial because I had control. I couldn't stand it when other people controlled my destiny or performance. Other jobs didn't inspire me to do my best, but waitressing did because I was accountable to myself. Eventually I got fired from these jobs because I didn't hesitate to tell the owners what I thought." Copyright Jeffry A. Timmons, 1997. This case was written by Rebecca Voorheis. under the direction of Jeffry A. Timmons, Franklin W. Olin Distinguished Professor of Entrepreneurship, Babson College. Funding provided by the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation. All rights reserved. Copyright The McGraw Hill Companies, Inc. Chapter 3 The Entrepreneurial Process 91 In 1984, Quimby began to question her lifestyle: "I decided I had to make a real income. I started to feel the responsibility of having kids. I had waitress- ing jobs but there were only three restaurants in town and I had been fired from all three. That's when I hooked up with Burt." making a few hundred dollars a day. She set what seemed like an impossible goal for the first year's sales-$10,000. That year, 1987, sales were $81,000. A Kindred Spirit Like Quimby, Burt Shavitz had dropped out in the early 1970s. A New York native and ex-photographer for Life and New York magazines, Shavitz livedin an 8-foot by 8-foot former turkey coop on a 20 acre farm in Dexter, Maine. A beekeeper with 30 hives, he earned maybe $3,000 a year selling honey during hunting season, which allowed him to pay property taxes and buy gas for his pickup truck. When Roxanne first saw Burt, whom she described as a "good-looker," she knew she had to meet him. In an article in Lear's magazine Quimby said, "I pre- tended I was interested in the bees, but I was really interested in Burt. Here was this lone beekeeper. I wanted to fix him, to tame the wild man." When they met in 1984, the bond was immediate. Quimby talked about Shavitz's role at Burt's Bees: I convinced Burt into this enterprise. He has always believed in my vision, but unlike me he's emotion- ally detached and uninvolved. Therefore, he has some great ideas and is more likely to take risks. He's my main sounding board and gives me a lot of moral and psychological support. I never could have done this without him. In all this time, there's never been a conflict between us. The chemistry has al- ways been there. We're just really on the same wavelength. We've been through a lot together that would have broken other relationships. I've always been the motivator and the one involved in day-to- day operations, but very rarely does he disagree with me. He's kind of my guru. Shavitz taught Quimby about beekeeping and Quimby discovered Shavitz's large stockpile of bees- wax. She made candles with the beeswax, took them to a local crafts fair and brought home $200. Burt's Bees' Early Success Burt's Bees' big break came in 1989 at a wholesale show in Springfield, Massachusetts. The owner of an upscale Manhattan boutique bought a teddy bear candle and put it in his store's window. The candle was a hit, and the boutique owner barraged the health food store with messages asking for new ship- ments. Quimby began hiring employees to help with production and expanded the product line to include other handmade crafts and beeswax-based products like lip balm. In 1993, Burt's Bees employed 44. Quimby explained her transformation into a businessperson: After a while, I realized I just liked it. I liked buying and selling things well, adding value. I had no security issues because I'd been living at the bottom for so many years. I knew if worse came to worse and the business failed, I could survive. I'd seen the worst and knew I could handle it. I'd never been trapped by the need for security or a regular paycheck. I loved the freedom of starting a business, of not knowing how it would turn out. It was this big experiment and whether it succeeded or failed totally depended on me. I real- ized the goal was not the most interesting part; the problems along the way were. I found business was the most incredibly liberating thing. I never would have thought that before. The only rule is that you have to make a little bit more than you spend. As long as you can do that, anything else you do is OK. There are no other opportunities that have as few rules. Quimby not only liked business, she was good at it. Burt's Bees had been profitable and seen its profits increase (Exhibit A) every year since its founding National retailers that stocked its products included L.L. Bean, Macy's, and Whole Foods, and it had sales representatives across the country and sold its earned maybe $3,000 a year selling honey during hunting season, which allowed him to pay property taxes and buy gas for his pickup truck. When Roxanne first saw Burt, whom she described as a "good-looker," she knew she had to meet him. In an article in Lear's magazine Quimby said, "I pre- tended I was interested in the bees, but I was really interested in Burt. Here was this lone beekeeper. I wanted to fix him, to tame the wild man." When they met in 1984, the bond was immediate. Quimby talked about Shavitz's role at Burt's Bees: I convinced Burt into this enterprise. He has always believed in my vision, but unlike me he's emotion- ally detached and uninvolved. Therefore, he has some great ideas and is more likely to take risks. He's my main sounding board and gives me a lot of moral and psychological support. I never could have done this without him. In all this time, there's never been a conflict between us. The chemistry has al- ways been there. We're just really on the same wavelength. We've been through a lot together that would have broken other relationships. I've always been the motivator and the one involved in day-to- day operations, but very rarely does he disagree with me. He's kind of my guru. Shavitz taught Quimby about beekeeping and Quimby discovered Shavitz's large stockpile of bees- wax. She made candles with the beeswax, took them to a local crafts fair and brought home $200. She remembers, "I had never held that much money in my hand." Burt's Bees was born. Quimby and Shavitz pooled $400 to launch a honey and beeswax business. They purchased some kitchen appliances for mixing, pouring, and dip- ping. A friend rented them an abandoned one- room schoolhouse with no heat, running water, windows, or electricity for $150 a year-the cost of the fire insurance. Neither had a phone, so they convinced the local health food store to take mes- sages for Burt's Bees. Quimby traveled to fair after fair, sleeping in the back of a pickup truck and 5. Bentham, "Enterprise," Lear's March 1994, pp. 20-21 production and expanded the product line to include other handmade crafts and beeswax-based products like lip balm. In 1993, Burt's Bees employed 44. Quimby explained her transformation into a businessperson: After a while, I realized I just liked it. I liked buying and selling things well, adding value. I had no security issues because I'd been living at the bottom for so many years. I knew if worse came to worse and the business failed, I could survive. I'd seen the worst and knew I could handle it. I'd never been trapped by the need for security or a regular paycheck. I loved the freedom of starting a business, of not knowing how it would turn out. It was this big experiment and whether it succeeded or failed totally depended on me. I real- ized the goal was not the most interesting part; the problems along the way were. I found business was the most incredibly liberating thing. I never would have thought that before. The only rule is that you have to make a little bit more than you spend. As long as you can do that, anything else you do is OK. There are no other opportunities that have as few rules. Quimby not only liked business, she was good at it. Burt's Bees had been profitable and seen its profits increase (Exhibit A) every year since its founding. National retailers that stocked its products included L.L. Bean, Macy's, and Whole Foods, and it had sales representatives across the country and sold its EXHIBIT A Burt's Bees Sales, 1987-1993 Year 1987 1988 Sales 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 $ 81,000 $ 137,779 $ 180,000 $ 500,000 $1,500,000 $2,500,000 $3,000,000 92 Part II The Opportunity products in every state. Quimby explained its prod- ucts' appeal: We sell really well in urban areas. People in urban areas need us more because they can't step out the front door and get freshness or simplicity. Our prod- ucts aren't sophisticated or sleek. They're down-home and basic. Everyone has an unconscious desire for more simplicity and our products speak to that need. The company was debt-free and had never taken out a loan. Quimby didn't even have a credit card. When she applied for one in 1993, by then a million- aire, her sister had to cosign because she had no credit history. She explained: I've never taken on debt because I don't ever want to feel like I can't walk away from it this afternoon. That's important to me. A monthly payment would trap me into having to explain my actions. I love being on the edge with no predictability, no one to report to. Quimby was so debt-averse and cash-aware, she refused to sell products to any retailer that didn't pay its bill within 30 days. That meant refusing orders from retailing powerhouses like I. Magnin and Dean & Deluca. In 1993, with about $3 million in sales, the company wrote off only $2,500 in uncollected debts. That year, Burt's Bees had $800,000 in the bank, and pretax profits of 35 percent of sales. beyond me, my expertise, my goals, and definitely beyond Maine. If I kept it in northern Maine, I would have stunted its growth. But the business was my child in a way, and as its mother I wanted to enable it to grow. The business provided a great income and I could have gone on like that for a while. But I knew it had a lot more potential than $3 million. At the same time, I knew $3 million was the most I could do on my own. I was working all of the time and there was no one to lean on or delegate to. Why North Carolina? Quimby felt she had to move the company away from Maine. But to where? She didn't want to live in a big city, but the new location had to be cen- tral. Quimby explained how she finally chose North Carolina: I had a map of the United States in my office with pins where all of our sales reps were. I used to al- ways look at that map-when I was on the phone, doing paperwork, or just sitting at my desk-until one day I noticed North Carolina. It just seemed central, well placed. And, it turned out, a large per- centage of the country's population lives within a 12-hour drive of North Carolina. One of my biggest worries about moving was telling Burt. I said to Burt one day, "We need to move and it looks like North Carolina is the place to go." Burt said, "OK, Roxy," and I thought to myself, "Thank God Burt is always on my wavelength." Shavitz called the North Carolina Department of Commerce and told him about Burt's Bees. North Carolina was aggressively recruiting companies and was eager to attract Burt's Bees, even though it was much smaller than other companies locating in the "Triangle."2 The North Carolina Department of Com- merce sent Burt's Bees a software program that Quimby used to calculate the taxes Burt's Bees would pay in North Carolina. They were significantly less than the taxes it paid in Maine. The Move The Costs of Doing Business in Maine Despite its success, Burt's Bees faced three problems due to its northern Maine location: 1. High transport costs: Since it wasn't near any metropolitan areas, Burt's Bees paid a fortune to ship products and receive materials. 2. High payroll taxes: Burt's Bees was being taxed about 10 percent of its payroll by the state of Maine. 3. Lack of expertise: In 1993 Burt's Bees had I've never taken on debt because I don't ever want to feel like I can't walk away from it this afternoon That's important to me. A monthly payment would trap me into having to explain my actions. I love being on the edge with no predictability, no one to report to. Quimby was so debt-averse and cash-aware, she refused to sell products to any retailer that didn't pay its bill within 30 days. That meant refusing orders from retailing powerhouses like I. Magnin and Dean & Deluca. In 1993, with about $3 million in sales, the company wrote off only $2,500 in uncollected debts. That year, Burt's Bees had $800,000 in the bank, and pretax profits of 35 percent of sales. The Move The Costs of Doing Business in Maine Despite its success, Burt's Bees faced three problems due to its northern Maine location: 1. High transport costs: Since it wasn't near any metropolitan areas, Burt's Bees paid a fortune to ship products and receive materials. 2. High payroll taxes: Burt's Bees was being taxed about 10 percent of its payroll by the state of Maine. 3. Lack of expertise: In 1993 Burt's Bees had 44 employees, who Quimby said "brought a set of hands and a good attitude to work, but no skills." As a result, the company made everything by hand. "When we received a shipment of con- tainers or labels, we had to break down the pal- lets inside the truck because no one knew how to operate a forklift," Quimby said. "There weren't any people with expertise in Maine." Additionally, Burt's Bees had struggled to keep up with demand since its start. Quimby couldn't focus on broad management issues because she spent most of her time pouring beeswax alongside Burt's Bees' other workers. She explained, The business had developed a life of its own and it was telling me it wanted to grow. But it was growing Quimby felt she had to move the company away from Maine. But to where? She didn't want to live in a big city, but the new location had to be cen- tral. Quimby explained how she finally chose North Carolina: I had a map of the United States in my office with pins where all of our sales reps were. I used to al- ways look at that map-when I was on the phone, doing paperwork, or just sitting at my desk-until one day I noticed North Carolina. It just seemed central, well placed. And, it turned out, a large per- centage of the country's population lives within a 12-hour drive of North Carolina. One of my biggest worries about moving was telling Burt. I said to Burt one day, "We need to move and it looks like North Carolina is the place to go." Burt said, "OK, Roxy," and I thought to myself, "Thank God Burt is always on my wavelength." Shavitz called the North Carolina Department of Commerce and told him about Burt's Bees. North Carolina was aggressively recruiting companies and was eager to attract Burt's Bees, even though it was much smaller than other companies locating in the "Triangle"? The North Carolina Department of Com- merce sent Burt's Bees a software program that Quimby used to calculate the taxes Burt's Bees would pay in North Carolina. They were significantly less than the taxes it paid in Maine. Even better was the large supply of skilled labor in North Carolina. If Burt's Bees moved, it could hire an ex-Revlon plant engineer to establish and operate its manufacturing facility. Quimby also had a lead on a marketing manager in North Carolina with experience at Lancome, Vogue, and Victoria's Secret's personal care products division The North Carolina Department of Commerce invited Quimby and Shavitz to tour the Triangle area and available manufacturing facilities. A representa- tive "took us around the whole area for 3 days." Copyright The McGraw Hill Companies, Inc. The "Triangle" area in North Carolina includes Chapel Hill, Raleigh, and Dur- ham and is the home of Research Triangle Park, a large high-tech busi- ness park similar to Silicon Valley in California or Route 128 in Massachusetts Chapter 3 The Entrepreneurial Process 93 Quimby said. "He showed us tons of plants and real Trimming the Azalea Bush: The estate. He made us a great offer and we were impressed." Economics of the Move When they got back to Maine, Quimby called the Maine Department of Commerce to give it a Roxanne Quimby likened Burt's Bees' move to transplant- chance to keep Burt's Bees in the state. "If they had ing an azalea bush in full bloom. She said, "I realized I offered us half the deal North Carolina did," Quimby had to trim and prune radically to allow it to survive." said, "I would have taken it." The Maine Depart- In Maine, Burt's Bees biggest resource was cheap ment of Commerce asked her to call back in a cou- labor-production line workers earned $5 an hour. ple of months because the person in charge of Therefore, most of its products were very labor- business recruiting was out on maternity leave. intensive and all were handmade. Quimby marveled, "We were the second largest In North Carolina, the company's biggest resource employer in the town and they didn't respond to us was skilled labor. But skilled labor is expensive, so at all. We finally heard from the governor of Maine Burt's Bees wouldn't be able to keep making labor- when he read an article about us in Forbes that intensive items. It would have to automate everything mentioned we were leaving the state. By then it and change its product line to skin care products (see was too late." Exhibit B for industry employment statistics). EXHIBIT B Occupations Employed by Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) 284: Soap, Cleaners, and Toilet Goods Occupation % of Industry Total, 1994 % Change to 2005 (Projected) Packaging and filling machine operators - 30.1 Hand packers and packagers 6.3 -20.1 Assemblers, fabricators, and hand workers 5.7 16.5 Sales and related workers 16.5 Freight, stock and material movers, hand Secretaries, executive, legal and medical Chemical equipment controllers, operators Industrial machinery mechanics Machine operators 2.6 Industrial truck and tractor operators Chemists Crushing and mixing machine operators 2.5 General managers and top executives 10.5 Traffic, shipping, and receiving clerks Marketing, advertising, and PR managers Science and mathematics technicians 16.5 Bookkeeping, accounting, and auditing clerks 1.8 16.5 Maintenance repairers, general utility 1.7 Inspectors, testers and graders, precision General office clerks -.7 8.5 4.9 3.6 3.5 3.0 2.7 2.6 2.6 2.5 -6.8 6.0 4.8 28.1 16.5 28.1 16.4 2.5 2.2 2.0 18 12.1 16.5 4.8 16.5 1.6 1.6 16.5 -6.8 6.0 16.5 2.6 2.5 when he read an article about us in Forbes that intensive items. It would have to automate everything mentioned we were leaving the state. By then it and change its product line to skin care products (see was too late." Exhibit B for industry employment statistics). EXHIBITB Occupations Employed by Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) 284: Soap, Cleaners, and Toilet Goods Occupation % of Industry Total, 1994 % Change to 2005 (Projected) Packaging and filling machine operators 8.5 - 30.1 Hand packers and packagers 6.3 -20.1 Assemblers, fabricators, and hand workers 5.7 16.5 Sales and related workers 4.9 Freight, stock and material movers, hand 3.6 Secretaries, executive, legal and medical 3.5 Chemical equipment controllers, operators 3.0 4.8 Industrial machinery mechanics 2.7 28.1 Machine operators 2.6 2.6 Industrial truck and tractor operators Chemists 28.1 Crushing and mixing machine operators 2.5 General managers and top executives Traffic, shipping, and receiving clerks Marketing, advertising, and PR managers Science and mathematics technicians 1.8 16.5 Bookkeeping, accounting, and auditing clerks Maintenance repairers, general utility Inspectors, testers and graders, precision General office clerks Order clerks, materials, merchandise and service 13.9 Machine feeders and offbearers 1.5 4.8 Clerical supervisors and managers Professional workers 39.7 Industrial production managers 16.4 Stock clerks -5.3 Managers and administrators Adjustment clerks 39.8 Accountants and auditors Management support workers Engineering, mathematical, and science managers 32.2 Truck drivers, light and heavy 10 20.1 Source: Manufacturing USA: Industry Analyses, Statistics, and Leading Companies, 5th ed, vol. I, ed. A. J. Darnay, Gale Research Inc. (1996), p. 837. D.W. Linder, "Dear Dad," Forbes, December 6, 1993, pp. 98-99. 2.5 2.2 2.0 16.4 10.5 12.1 16.5 1.8 1.7 1.6 1.6 16.5 4.8 16.5 -.7 1.5 19.1 1.5 1.4 1.4 16.4 1.3 1.2 1.2 LI 16.5 16.4 Copyright The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 94 Part II The Opportunity Skin care products (for general industry statistics, see Exhibits C and D) require only blending and fill- ing, almost all of which can be done by machinery "To justify the move to North Carolina from a cost and manufacturing perspective, we would have to make more 'goop,'" Quimby stated. "I looked at my list of prospective new products, and there wasn't anything on the list that we made in 1988." EXHIBITC General Industry Statistics for SIC 2844: Toilet Preparations Establishments Employment Compensation Production ($million) Production Production Value With = 20 Total Workers Hours Payroll Wages Cost of Added by Value of Capital Year Total Employees coos) (00s) (mil) (Smil) ($/hour) Materials Manufacture Shipments Investment 1988 687 277 64.9 40.5 78.1 1,5513 9.08 4,445.1 12,053.2 16,293.6 292.6 1989 676 282 63.6 39.4 75.4 1,615.5 9.69 4,758.2 11,979.2 16,641.9 313.7 1990 682 284 63.6 38.1 74.3 1,620.6 10.14 4,904.6 12,104.2 17,048.4 280.4 1991 674 271 57.4 35.6 69.8 1,616.3 10.81 5,046.3 12,047.4 18,753.5 299.5 1992 756 305 60.1 37.2 75.6 1,783.3 10.82 5,611.3 13,1672 19.706.4 507.3 1993 778 299 61.7 38.6 79.7 1,857.8 10.59 6,152.6 13,588.8 19,736.0 472.6 Manufacturing USA: Industry Analyses, Statistics, and Leading Companies, 5th ed., vol. I, ed. A. J. Darnay, Gale Research Inc. (1996), p. 833 Sources: 1982, 1987, 1992 Economic Census; Annual Survey of Manufactures, pp. 83-86, 88-91, 93-94. Establishment counts for noncensus years are from County Business Patterns EXHIBITD Comparison of Toilet Preparations Industry (SIC 2844) to the Average of All U.S. Manufacturing Sectors, 1994 All Manufacturing Selected Measurement Sectors Average SIC 2844 Average Index Employees per establishment 49 77 157 Payroll per establishment $1,500,273 $ 2,397,065 Payroll per employee $ 30,620 $ 31,191 102 Production workers per establishment 34 47 137 Wages per establishment $ 853,319 $ 1,061,646 124 Wages per production worker $ 24,861 $ 22,541 91 Hours per production worker 2,056 2,062 100 Wages per hour $ 12.09 $ 10.93 90 Value added per establishment $4,602,255 $17,781,454 386 160 9.69 10.14 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 676 682 674 756 778 282 284 271 305 299 63.6 63.6 57.4 60.1 39.4 38.1 35.6 37.2 38.6 75.4 74.3 69.8 756 79.7 1,615.5 1,620.6 1,616.3 1,783.3 1,857.8 10.81 10.82 10.59 4,758.2 4,904.6 5,046.3 5,611.3 6,152.6 11,979.2 12,104.2 12,047.4 13,1672 13,588.8 16,641.9 17,048.4 18,753.5 19.706.4 19,736.0 313.7 280.4 299.5 507.3 472.6 61.7 Manufacturing USA: Industry Analyses, Statistics, and Leading Companies, 5th ed., vol. I, ed. A. J. Darnay, Gale Research Inc. (1996), p. 833 Sources: 1982, 1987, 1992 Economic Census; Annual Survey of Manufactures, pp. 83-86, 88-91, 93-94. Establishment counts for noncensus years are from County Business Patterns EXHIBIT D Comparison of Toilet Preparations Industry (SIC 2844) to the Average of All U.S. Manufacturing Sectors, 1994 All Manufacturing Selected Measurement Sectors Average SIC 2844 Average Index Employees per establishment 49 77 157 Payroll per establishment $ 1,500,273 $2,397,065 160 Payroll per employee $ 30,620 $ 31,191 102 Production workers per establishment 34 47 137 Wages per establishment $ 853,319 $ 1,061,646 124 Wages per production worker $ 24,861 $ 22,541 91 Hours per production worker 2,056 2,062 100 Wages per hour $ 12.09 $ 10.93 Value added per establishment $4,602,255 $17,781,454 386 Value added per employee $ 93,930 $ 231,375 246 Value added per production worker $ 134,084 $ 377,541 282 Cost per establishment $ 5,045,178 $8,648,566 171 Cost per employee $ 102,970 $ 112,536 109 Cost per production worker $ 146,988 $ 183,629 125 Shipments per establishment 9,576,895 26,332,221 275 Shipments per employee 195,460 342,639 175 Shipments per production worker 279,017 559,093 200 Investment per establishment $ 321,011 $ 654,570 204 Investment per employee $ 6,552 $ 8,517 130 Investment per production worker $ 9,352 $ 13,898 149 90 Copyright The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. "Manufacturing USA: Industry Analyses, Statistics, and Leading Companies, 5th ed, vol. I, ed. A. J. Darnay, Gale Research Inc. (1996), p. 833 Chapter 3 The Entrepreneurial Process 95 Quimby planned on retaining Burt's Bees environ- mental ethic by using primarily natural ingredients- and no chemical preservatives-in its skin care products. Still, though, Burt's Bees would have to become an entirely new company and abandon the product line responsible for its success. Quimby also realized she and Shavitz couldn't remain the sole owners of the company if she wanted it to grow. Since the inception of Burt's Bees, Roxanne and Burt had held 70 percent and 30 percent of its stock, respectively. Quimby knew the employees she hoped to attract would be highly motivated by stock grants. She also knew sharing ownership would mean feeling accountable to others and having to justify her sometimes unorthodox decisions. Quimby had fought her whole life to avoid accountability and her auton- omy was a reason for Burt's Bees' success. on a plant manager from Revlon and a sales and marketing manager with experience at Lancome, Vogue, and Victoria's Secret. The two would largely fill Quimby's expertise deficit. 2. Move back to Maine: Quimby could halt all purchasing and hiring and move back to Maine. She could minimize the sunk costs by acting quickly. Additionally, Burt's Bees could keep its original product line. Maine's gover- nor had told her to call if she changed her mind. She could pursue a deal Maine to miti- gate the company's tax, transport, and employment costs. 3. Sell the company: Although having only $3 million in sales might be an obstacle, Burt's Bees had received a lot of attention and would be enticing to many prospective buyers. Quimby knew she didn't want to be at Burt's Bees forever and said, "I feel like at some point, this business isn't going to need me any- more. My child will grow up and want to move away from its mother. There are other things I want to do." Conclusion Quimby walked around the empty North Carolina factory. She tried to imagine the empty space filled with machinery and workers, but her mind kept going back to the old schoolhouse in Maine. As she saw it, Quimby had three choices: 1. Stay in North Carolina: Quimby could com- mit to North Carolina and try to get over her doubts. Burt's Bees had promising leadsStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts