Question: This question relates to the Yushan Bicycles Case. Using the relevant readings from class up until now, summarize Yushan's evolution as a multinational company as

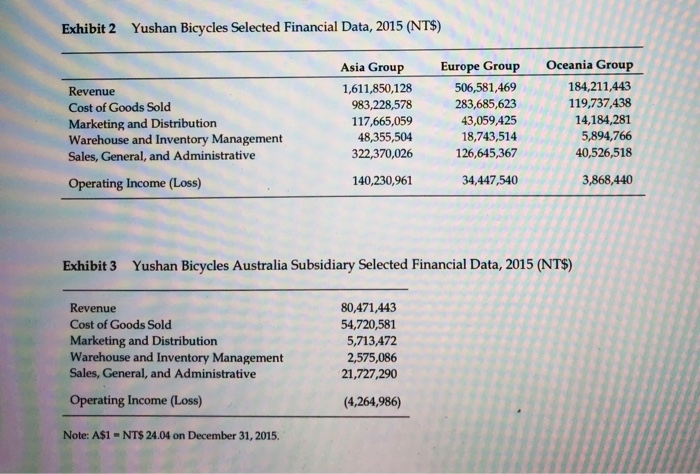

This question relates to the Yushan Bicycles Case. Using the relevant readings from class up until now, summarize Yushan's evolution as a multinational company as the company moved offshore and operated in more than one country. In your answer be sure to discuss the following: How Yushan's competitive strategies varied in the various countries/regions it entered. The main challenges or pressures from the business/industry the company as a whole faced as it expanded to new regions. The company's response in terms of the capabilities was building and the international approach /mentality it was working towards. Yushan Bicycles: Learning to Ride Abroad In March 2016, the growing tension between senior management at Yushan Bicycles (Yushan) and the general manager of its Australian subsidiary came to a head at a management meeting in Taiwan. An unexpectedly large quarterly loss at Yushan Australia (YA) led Chih-hao Zonghan, Yushan's director of global sales operations, to consider exercising tighter control over YA. Zonghan was even more concerned about the unconventional strategy that YA's general manager, James Hamilton, was pursuing Hamilton, on the other hand, felt he was responding appropriately to Australian consumer preferences and distribution channel prospects, and was unhappy with what he saw as interference in his operations. He felt the parent company had contributed significantly to his subsidiary's setback due to its problems supplying products and transfer pricing issues. He was looking for a quick resolution. Company Background and Expansion Yan-Ting Hsieh and Zhiwen Tseng, both semiprofessional cyclists, started Yushan Bicycles in 1985, naming their company after Taiwan's highest mountain. Yushan's headquarters and manufacturing operations were in Taichung, Taiwan, home to almost 600 bicycle companies, which created a close- knit supply chain, from component makers to distributors. China led the world in bicycle production, but Taiwanese manufacturers generally made midrange to high-end products of superior quality. Yushan was the seventh-largest bike manufacturer in Taiwan, producing 200,000 bicycles a year. It fabricated frames from aluminum, titanium, and carbon fiber, and it sourced components such as drivetrains, brakes, seats, wheels, handlebars, and pedals from local suppliers. Its 25,000-square-foot factory employed 260 people. Unlike most other Taiwanese bicycle companies, Yushan had from the outset designed, produced, and branded its own product line, selling through specialty bicycle stores throughout Taiwan. Its bikes emphasized comfort and performance and were distinguished by their streamlined shapes and distinctive colors. The company's product line included road bikes designed to be ridden on smooth pavement; touring bikes suited to long-distance rides; mountain bikes intended for rugged terrain; aerodynamic sport/performance bikes, and hybrids that combined features of road and mountain bikes and were well-suited for commuting. Within each bicycle type, Yushan offered several models that were differentiated by frame design and size, handlebar style, number of gears, and saddle. Yushan targeted a wide range of consumers, from those seeking basic bicycles at a reasonable price to experienced cyclists willing to pay more for additional attributes and performance. In recent years, it had shifted its product mix to favor the latter category of buyer and thereby capture the larger margins this segment offered. In 2007, Yushan introduced its first electric bicycle. With their rechargeable battery-powered motors, electric bikes enabled riders to maintain a constant speed on flat or inclined roads at speeds of up to 28 miles per hour, although local speed limits were often lower. Unlike a traditional motorbike or moped, the e-bike motor engaged only when the rider was pedaling. An e-bike could travel 40 miles or more on one charge. To produce its e-bikes, Yushan used similar frames and many of the same components as it did for its conventional bicycles. Liu Chen, who oversaw the company's manufacturing operations, believed that as production of e-bikes reached scale, their profit margins would be at least double those of Yushan's conventional bikes. Yushan's International Strategy With growth in its domestic market slowing and local demand concentrated on Yushan's less expensive models, Hsieh and Tseng decided to expand internationally not only to capture production scale economies, but also to upgrade the product mix. Yushan's first overseas foray came in 2006, when it began exporting to Singapore. Two years later, it successfully entered the Japanese market, where, just as in Taiwan, the distribution channels were dominated by specialty retailers. Sales in the Asia Group built steadily, but there was increasing demand for higher-end models. Zonghan, a hard-driving executive with a lifetime of sales experience in the Taiwanese bicycle industry, was particularly pleased with Japanese e-bike sales. Since their introduction in the 1990s, e-bikes had proved extremely popular with Japanese women The second phase of Yushan's international thrust came with the creation of the Europe Group, one of Taiwan's largest bicycle export markets. Approximately 10% of the 20 million bicycles sold across Europe annually were imported from Taiwan, the highest demand coming from consumers seeking higher-end models. Hsieh and Tseng believed that, in addition to providing increased volume, Yushan needed to learn from more sophisticated European consumers. Specialty bicycle retailers represented the dominant channel in most European countries, ranging from a 43% market share in France to a 72% share in the Netherlands. At the same time, e-bikes were gaining popularity: sales were growing by more than 20% per annum. Demand came not only from affluent, environmentally conscious commuters but also increasingly from commercial users for tasks such as package delivery. In 2010, in anticipation of expanded demand, the company expanded its factory capacity and increased the proportion of space used to produce the titanium and carbon-fiber frames used in higher-priced bicycles. It also increased its production capacity for e-bikes. Competitors in the European market were well entrenched, and it was difficult for newcomers like Yushan to gain share. While trying to build its share through traditional distribution strategies, the company also began pursuing a parallel strategy. Following a chance meeting between Hsieh and a trade minister from Poland, Yushan's Europe Group also started to focus opportunistically on contracts for large-volume sales in Eastern Europe, particularly new urban bike-share programs. In 2013, Yushan launched the third leg of its international expansion strategy by establishing sales subsidiaries in Australia, New Zealand, and Indonesia. Chen suggested the seasonal peaks in demand in the Southern Hemisphere would help him balance production schedules. Furthermore, because penetration of the European market was slow and difficult, Zonghan believed the Australian and New Zealand markets could provide knowledge and experience that would be valuable in Yushan's eventual planned entry into the United States. As the international strategy evolved, so did the company's organizational structure (see Exhibit 1). Manufacturing operations were centralized and operated as a profit center. Functional departments such as engineering personnel, and marketing were also located in Taichung and were designated as cost centers. To manage the scope and complexity of the unfamiliar international operations, Zonghan appointed three regional group managers to oversee subsidiaries in Asia, Europe, and Oceania Subsidiaries in Australia, New Zealand, and Indonesia reported to Zonghan through the Oceania Group, led by Wei Yeh, a 40-year-old manager newly recruited from a Taiwanese export company. All subsidiaries were autonomous profit centers reporting to the group managers, all located at Yushan's headquarters. Country subsidiary managers had considerable freedom to adapt approaches for their local markets. They were also required to propose annual sales and profit objectives. By late 2015, the Asia Group (including domestic Taiwan sales) accounted for 70% of revenue, the Europe Group provided 22%, and the Oceania Group contributed the remaining 8%. Profitability varied even more widely by group. Exhibit 2 provides selected financial information. Yushan in Australia Australia was one of the top-ten destinations for Taiwan bicycle exports. Although the market for less expensive models was larger in Indonesia, Zonghan believed YA was Yushan's strategically most important subsidiary in Oceania. He was aware that 17% of Australia's 23 million people -21% of males and 12% of females rode a bike at least weekly. Although the e-bike market was still in its infancy, he believed that the country's pleasant climate, outdoor lifestyle, and large cities with many commuters would make Australia a natural fit for this product. Australian Market Structure In Australia, around 1,000 independent specialty bicycle retail shops were the primary channels serving the needs of cyclists. They stocked a range of bike types, styles, and price points to cater not only to bike enthusiasts but also to quality-oriented casual riders; these outlets had an estimated 45% share of the bicycle market. At the other end of the spectrum, mass merchandisers such as Big W, Kmart, and Target sold lower-priced bicycles, including children's models, sourced mostly from China. They were estimated to have less than 10% of the market. In contrast to most other countries where Yushan operated, Australia had another important channel positioned between these traditional retailers. Sporting-goods chains like Rebel and Amart Sports carried a focused array of midrange and higher-end bikes and were estimated to have 35% of the market. In these stores, bicycles from Taiwan typically sold for 10% to 15% more than lower-quality models produced in China did. It was predicted this segment would be disrupted by the arrival of French-based Decathlon. As the world's largest sporting-goods retailer, Decathlon planned to open 35 warehouse-style stores in Australia by 2020. In the e-bike segment, Australia was in the early stages of adoption, with low volume and low consumer awareness. In contrast to the Japanese market, early adopters in Australia seemed to be primarily male commuters. As the market developed, a 2012 federal government regulation increased its attractiveness. E-bikes with a power output of 250 watts or less were now classified as bicycles and therefore did not require a license or registration, as motorbikes did. Priced between A$2,000 and A$3,000, e-bikes were more expensive than the AS400 to A$1,300 cost of most traditional bikes. High- end bicycles, however, sold for as much as A$8,500. Australian sales of e-bikes were estimated at under 15,000 units in 2014. Several e-bike makers from Europe were exporting into the Australian market, but none had established itself as a market leader. Startup: Strategy and Organization James Hamilton was named general manager of YA in April 2013. Although he lacked familiarity with bicycles or sporting goods, he had 25 years of experience leading high-performance sales and marketing teams in several successful Australian consumer-goods companies. Like all Yushan's subsidiaries, YA was expected to become financially self-sufficient as quickly as possible. Hamilton lost little time building YA's operation from the ground up, while simultaneously developing a local strategy that fit into Yushan's objectives. Hamilton's first priorities were to hire staff, lease office and warehouse space, and develop relationships with distributors. By late 2013, he had begun to implement a strategy aimed at building volume quickly with the company's most popular road and touring bikes. Because he did not have the staff to penetrate Australia's multiplicity of widely dispersed independent specialty bicycle stores, he decided initially to target sporting-goods chains. In another deviation from the company's normal practice, Hamilton set prices at the lower end of the range for similar-quality bicycles on the market to build volume quickly Once a sales threshold of 10,000 units was met something he hoped to achieve within two to three years - Hamilton planned to raise prices, hoping to self-fund investment in the next phase of his strategy. This second stage would involve advertising to build Yushan's brand image, expanding distribution to specialty bicycle shops, and providing the service levels required to support its higher- end, higher-margin bicycles. He observed, "Until we build our brand and product reputation, the specialty retailers won't have any interest in us." Within his first four months, YA's new leader had built a staff of 15, comprising sales reps, marketing specialists, warehouse workers, and administrative personnel. The subsidiary was based in Melbourne, but, recognizing the country's large geographic expanse, Hamilton had begun opening sales offices in Sydney, Brisbane, and Perth. Because of his reputation and track record, as well as Taiwanese management's lack of familiarity with the Australian market, Yushan gave Hamilton considerable autonomy in both strategic and operational matters. 2016: Problems and Conflicts By December 2015, Yushan's bicycle sales in Australia had reached 5,960 units, and Hamilton felt he was making solid progress toward the 10,000-unit target he had set before he increased prices and upgraded the product mix. In the last quarter of 2015, however, YA reported results significantly below budget. See Exhibit 3 for YA's financial information. The unanticipated loss led to tensions between Yushan's headquarters and YA. Each offered different explanations for the poor results and different proposals for action needed. Transfer Pricing Conflicts Hamilton felt YA's losses were due in part to Yushan's transfer pricing policies, which were based on direct manufacturing costs, overhead allocation, a finance charge, and a markup to cover centralized services such as marketing and research and development. Hamilton and several of Yushan's other subsidiary managers felt that Yushan put the profitability of its Taiwan-based operations ahead of that of offshore subsidiaries. He felt subsidiaries were carrying a burden of factory costs they could not control and headquarters overhead from which they did not benefit. He had also heard that when big opportunities came up-such as bike-share contracts in large European cities--some subsidiaries had negotiated transfer prices that excluded overhead, thereby increasing the burden on other subsidiaries. Headquarters managers countered that transfer prices to Oceania were insufficient to cover even their share of marketing costs and technical expenditures from which they benefited. Equally frustrating to Hamilton was the unpredictability of transfer prices, which were adjusted quarterly to reflect increases in manufacturing costs. Zonghan defended the practice, explaining that Yushan was financially stretched by its international expansion and required subsidiaries to recoup cost increases. But the policy created difficulties in YA. When transfer prices rose sharply in the third quarter of 2015, YA had been unable to raise its local prices on a very large order accepted in May but scheduled for delivery over the following six months. This price increase ate up YA's margin on the sale. Hamilton particularly resented headquarters managers regarding this as his own error because he did not account for a possible increase in transfer prices during negotiations. Currency fluctuations posed another problem. For example, between January 2015 and September 2015, the Australian dollar (A$) lost 15% against the New Taiwan Dollar (NTS). Because transfer prices were stated in NTS, the subsidiary bore the costs of this weakening of the local currency, which significantly increased actual product costs above their budgeted cost of goods. Information Systems Problems Hamilton also pointed to problems with the company's new enterprise resource planning system, introduced in early 2015, to support Yushan's sales, distribution, and accounting functions. The system had incorrectly reported stock availability on several occasions, leading sales staff to make unrealistic delivery commitments. In one case the mistake led a new customer to cancel the order rather than accept the expected delay. Furthermore, owing to problems integrating cost data into the new database, subsidiary sales prices that the system generated by adding a margin to total cost per unit markup were inaccurate, often falling below the transfer price. Because the new system significantly increased the amount of time it took for YA sales staff to record orders, they saw it as unnecessarily complicated. During implementation, they made several mistakes that resulted in subsequent order corrections that disrupted plant production schedules. Hamilton blamed poor documentation and insufficient training for these errors, but Zonghan and Yeh felt the disruption was due to a lack of effort and poor attitude on the part of the Australian staff. Delivery Delays Hamilton also believed Yushan gave priority to deliveries to its established subsidiaries in Asia, which led him to question the company's commitment to Oceania. In June, for example, stock destined for Australia was diverted to fill a large order from Singapore's biggest customer. Expected shipments often arrived late, which Hamilton said made delivery commitments nearly impossible to keep. He worried YA would gain a reputation as an unreliable supplier, which would damage its ability to grow. Zonghan and Yeh saw the matter differently. Both were increasingly skeptical of YA's forecasts, and had developed a bias toward confirmed commitments from established markets over questionable assurances from a hopeful one. They also acknowledged that in times of product shortage, the rational corporate decision was to assign priority to sales to Japan, which provided more accurate forecasts and offered much higher margins than YA, which was budgeted to operate at breakeven. Headquarters' Response In late January 2016, after seeing YA's fourth-quarter results for 2015, Zonghan instructed Yeh to report on the causes of the unexpected losses in YA and to recommend changes to stop the financial bleeding. Following his scheduled quarterly trip to Melbourne in February, Yeh reported he was increasingly concerned that Hamilton had invested too quickly in staff and organization in the expectation that volume growth would absorb the fixed costs built into his strategic plan. Yeh confirmed he would ask Hamilton to commit to a 10% increase in profitability through a combination of a price hike and a reduction in fixed costs. Specifically, he wanted Hamilton to review the need for regional sales offices When he reviewed Yeh's report, Hamilton saw it as another example of distant Taiwanese management intervening in decisions when they had very little knowledge of the local situation. He pointed out that the increase from 6,000 to 10,000 units annually would require no additional staff or warehouse space. Even as volume approached 15,000 units annually, he estimated he would need to add only two additional staff. Regarding the price increase proposal, he cited an analysis his sales force had prepared following the recent transfer price problems. It concluded that intense competition from new branded imports was limiting the market's willingness to accept price increases. Meanwhile, Yeh also supported Chen's request for YA to update its forecasts weekly rather than monthly. Although YA's forecasts had been correct in the aggregate, estimates for specific models had not been reliable. This had created stock-outs, which led customers to question the company's supply reliability. It had also created a surplus of some models, which had to be sold at reduced prices to create warehouse space for arrivals of more popular stock items. Chen convinced Yeh more frequent updates would allow inventory to be managed more effectively. Hamilton viewed this change as an indication of a lack of trust in his judgment. He argued that YA was new to this market and was beginning only now to get a good sense of how to assess demand. The biggest issue worrying Zonghan was Hamilton's market-entry strategy, which seemed to be building share more slowly and less profitably than expected. Worse still, he had heard a rumor that a major Chinese e-bike competitor was planning to enter the Australian market. He was concerned that the longer YA waited to launch, the more likely it could be shut out altogether. Due to Yushan's experience in Japan and Singapore, Zonghan believed the established marketing approach for targeting potential e-bike buyers would work in Australia. Chen supported Zonghan, pointing to excess plant capacity as an opportunity to produce a larger number of e-bikes. Following discussions at headquarters, Zonghan and Yeh urged Hamilton to accelerate his plans to expand the product line to include higher-end models, particularly e-bikes. Hamilton responded that in his sales team's experience, retailers would carry only a limited range of bikes from each supplier, Overall, headquarters' increasing controls and its proposals on product strategy were taking away important elements of the autonomy he believed he needed to succeed. Meeting at Headquarters In March, Yushan had its annual management meeting in Taiwan, which it held in conjunction with the Taipei International Cycle Show. The meeting gave Hsieh and Tseng a platform for reiterating their goal of becoming one of the world's most respected bicycle brands. Yushan's senior managers, including Zonghan, Chen, and Yeh, attended, as did the heads of all overseas subsidiaries. Hsieh and Tseng opened the meeting by reaffirming each geographic group's role in Yushan's emerging strategy. Asia, which included the domestic market, would continue to be the largest source of sales and profit. Europe was to be managed opportunistically, gradually establishing a foothold at the high end while bidding on large contracts for urban bike-share programs to exploit factory capacity. Oceania represented Yushan's growth opportunity. Key objectives were to build distribution strength, upgrade the product mix, and learn from the new market experiences. As the meeting progressed through a review of 2015's results, each subsidiary manager was invited to comment on his or her unit's performance. In his introductory remarks, Zonghan identified YA as a concern, but said he expected additional controls and a change in strategy to correct the problem. When Hsieh asked Hamilton to comment, the Australian executive decided this request gave him an opportunity to express his concerns. After briefly outlining his strategy, Hamilton acknowledged YA had not yet achieved the volume and market penetration he was seeking. He argued, however, it was inappropriate and premature to cut sales offices, raise prices, or shift product strategy because his team needed more time to deliver on his plan. He believed attempting to upgrade the product focus or engage specialty bicycle retailers without sufficient resources to establish the brand or provide strong support risked failure. He also touched on the delivery and transfer pricing problems and suggested a lack of support from the administrative departments was also a concern. His proposed solution was to ask for another year to pursue his original strategy, as he was confident YA would achieve its objectives in that time. When Hamilton sat down, the silence was deafening. With the lunch break approaching, Hsieh suggested that Hamilton and Zonghan use that time to resolve their differences. When they reconvened after lunch, he expected to hear how they planned to move forward. Exhibit 2 Yushan Bicycles Selected Financial Data, 2015 (NT$) Revenue Cost of Goods Sold Marketing and Distribution Warehouse and Inventory Management Sales, General, and Administrative Operating Income (Loss) Asia Group 1,611,850,128 983,228,578 117,665,059 48,355,504 322,370,026 140,230,961 Europe Group 506,581,469 283,685,623 43,059,425 18,743,514 126,645,367 Oceania Group 184,211,443 119,737,438 14,184,281 5,894,766 40,526,518 34,447,540 3,868,440 Exhibit 3 Yushan Bicycles Australia Subsidiary Selected Financial Data, 2015 (NT$) Revenue Cost of Goods Sold Marketing and Distribution Warehouse and Inventory Management Sales, General, and Administrative Operating Income (Loss) 80,471,443 54,720,581 5,713,472 2,575,086 21,727,290 (4,264,986) Note: A$1 - NT$ 24.04 on December 31, 2015