Question: USE THESE TO HELP: ASSIGNMENT : Answer this ethical problem. Formulate a personal response to the possible decisions or actions a leader in that position

USE THESE TO HELP:

USE THESE TO HELP:

ASSIGNMENT: Answer this ethical problem. Formulate a personal response to the possible decisions or actions a leader in that position would face. Using the theories, models, and processes covered in the class. Describe the rationale behind supporting their position as well as using themes and content discussed in the course. Include an examination into all critiques and opposite viewpoints of such a position, with emphasis directed as to how those viewpoints could emerge through moral reasoning in at least 1200 words.

ASSIGNMENT: Answer this ethical problem. Formulate a personal response to the possible decisions or actions a leader in that position would face. Using the theories, models, and processes covered in the class. Describe the rationale behind supporting their position as well as using themes and content discussed in the course. Include an examination into all critiques and opposite viewpoints of such a position, with emphasis directed as to how those viewpoints could emerge through moral reasoning in at least 1200 words.

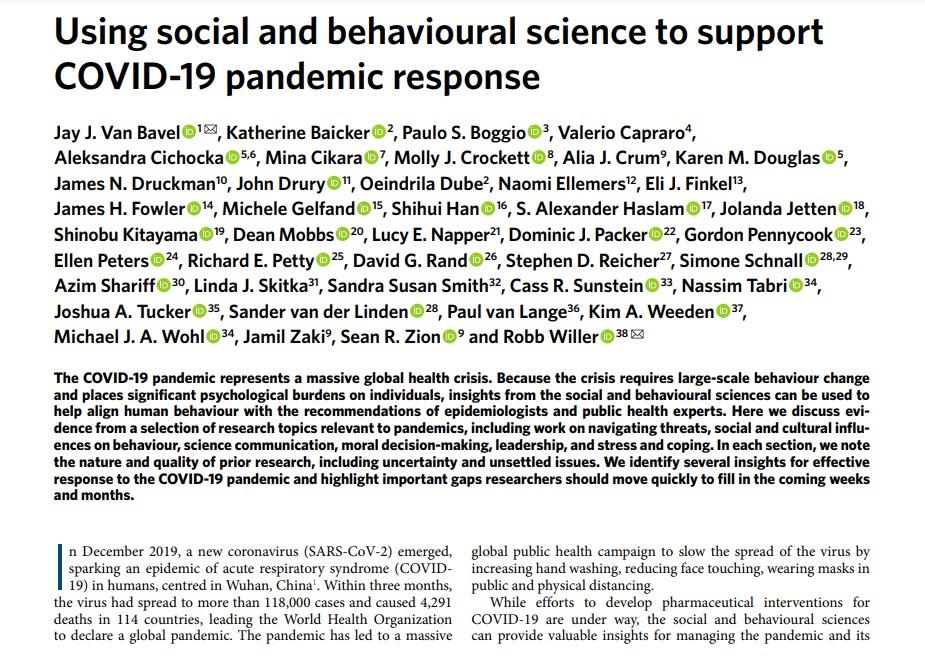

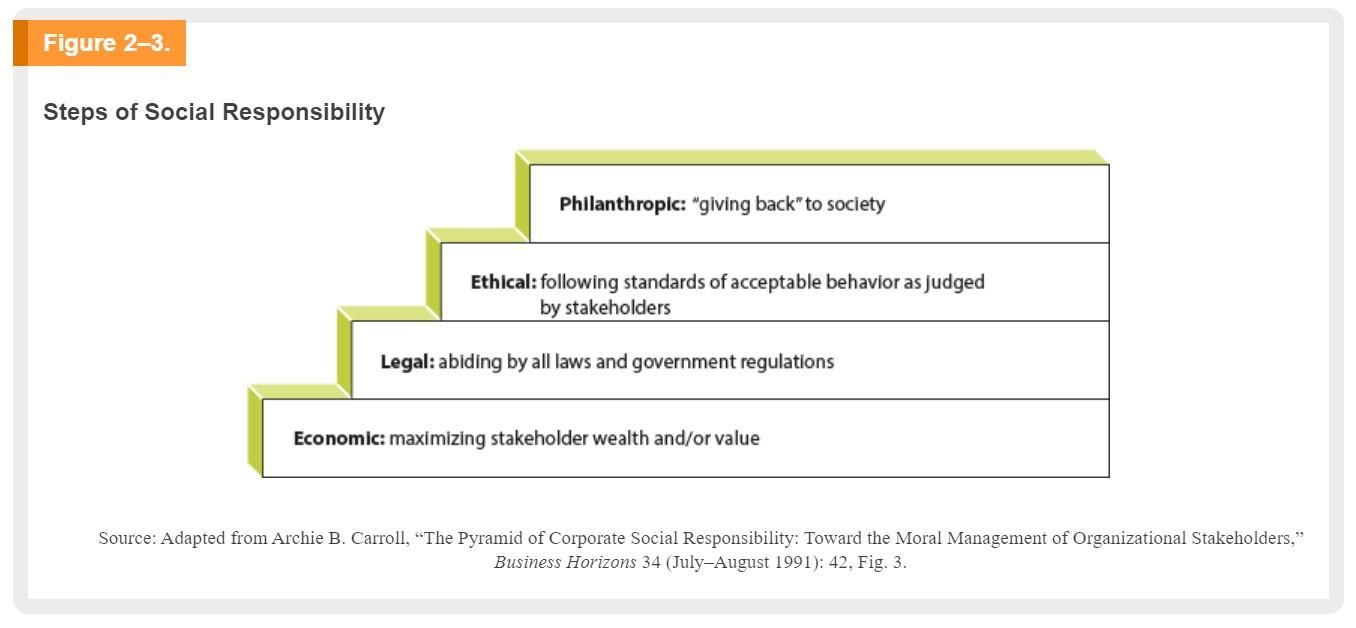

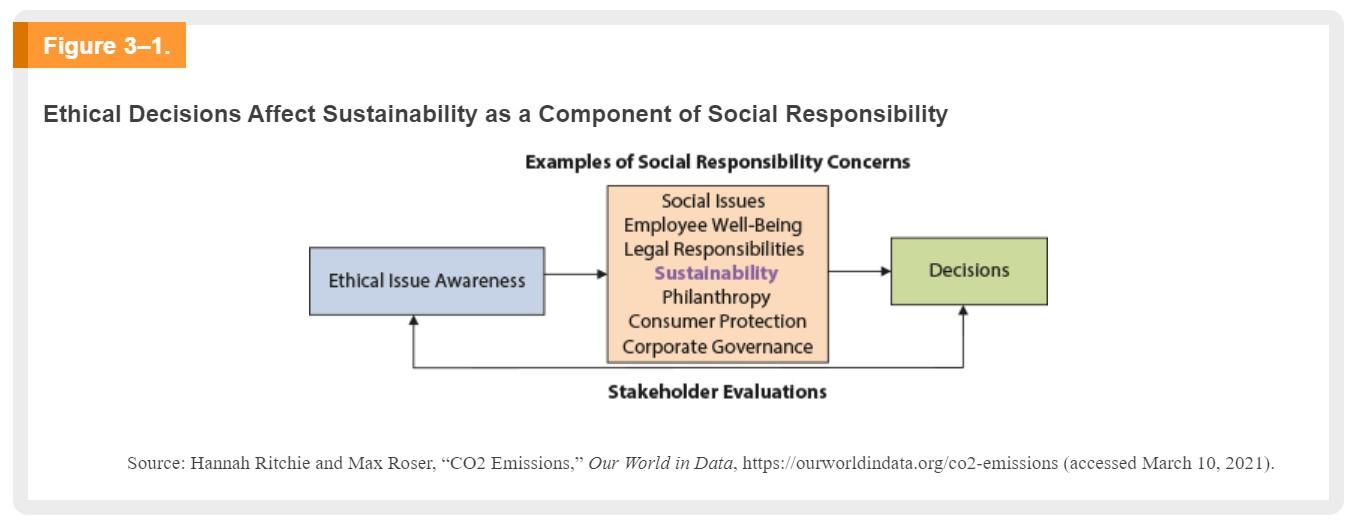

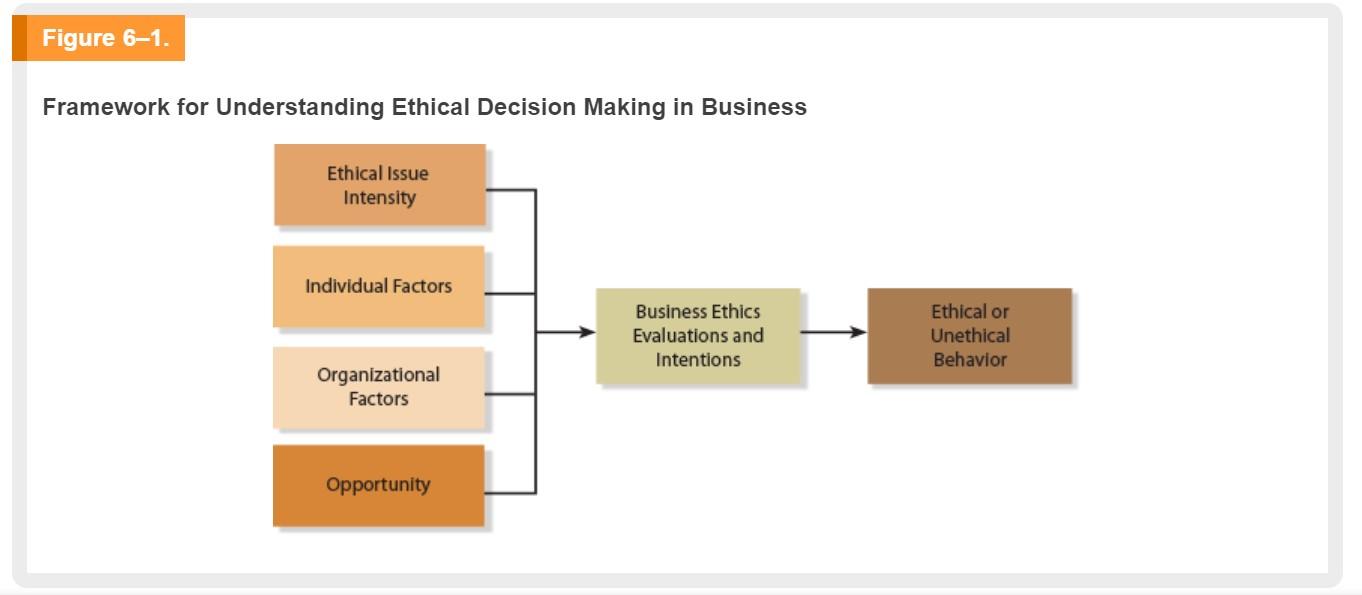

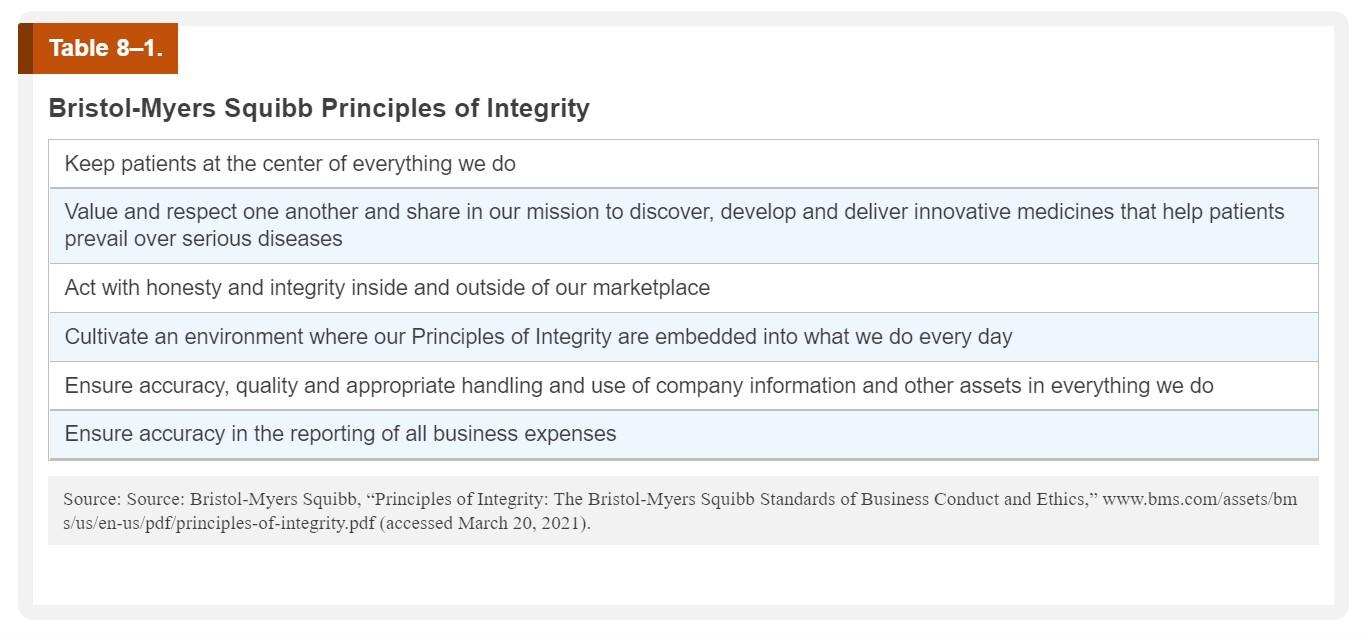

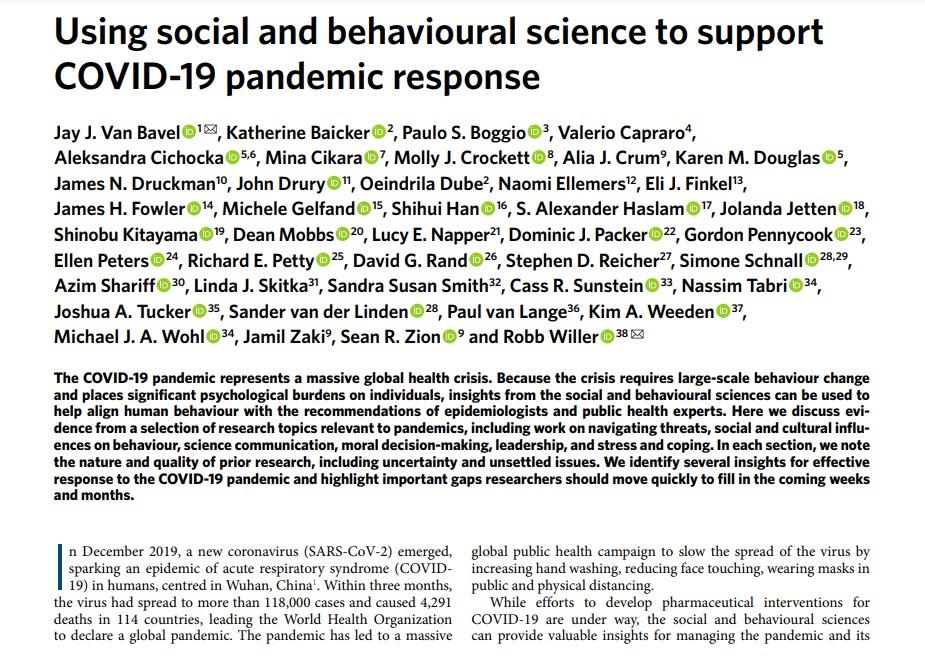

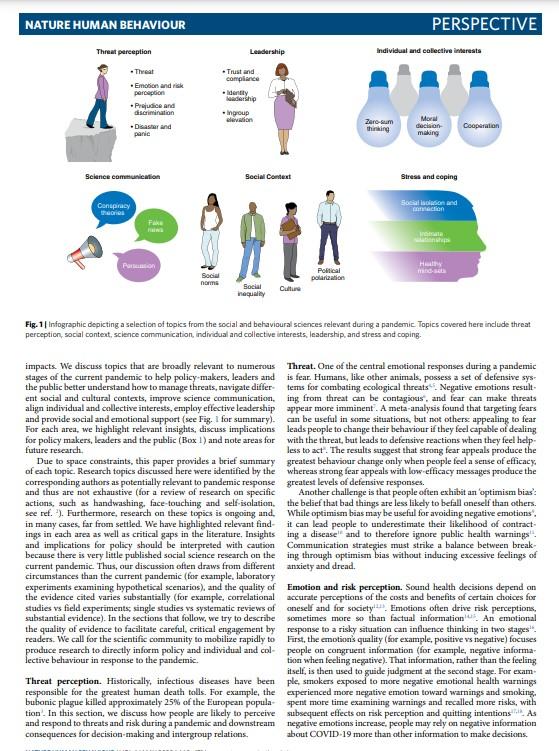

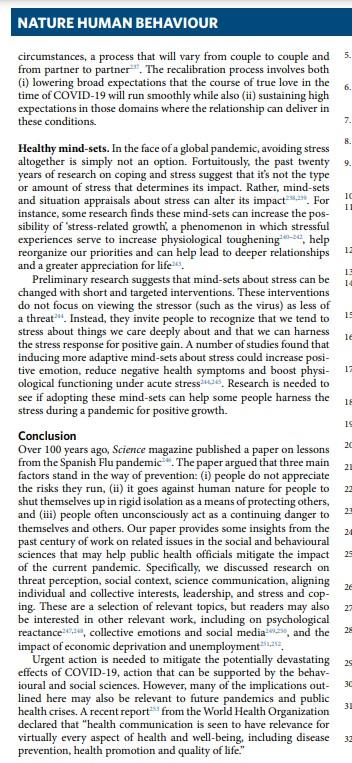

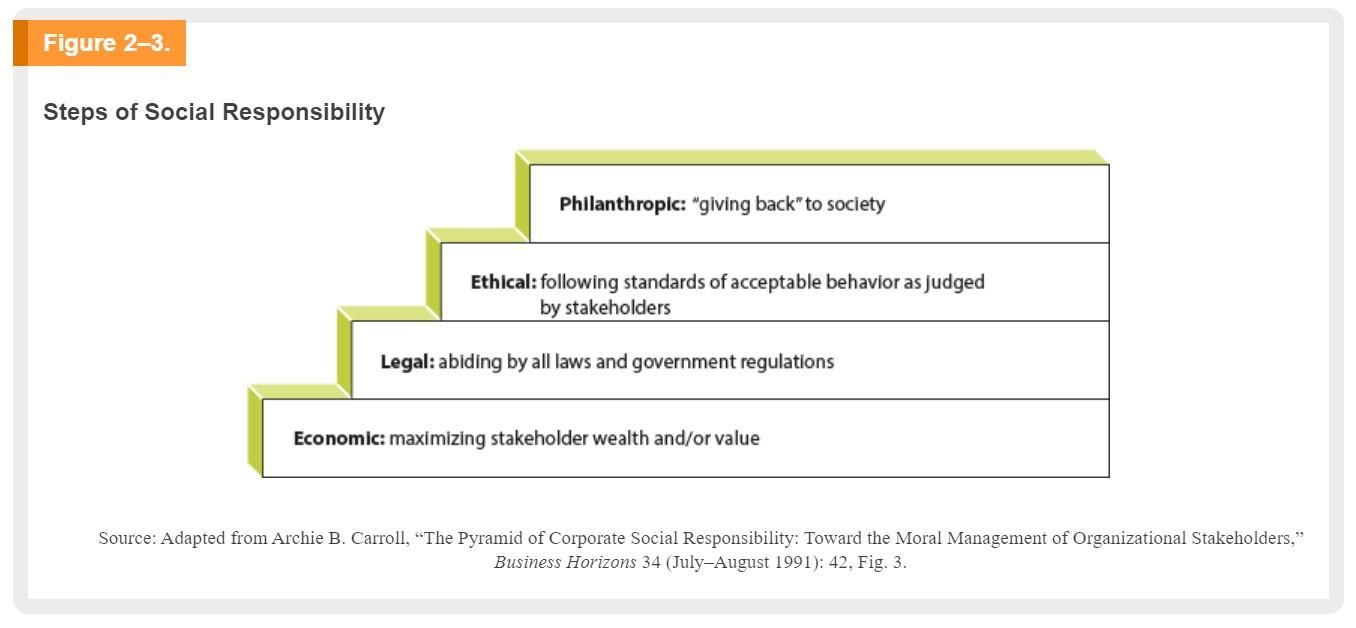

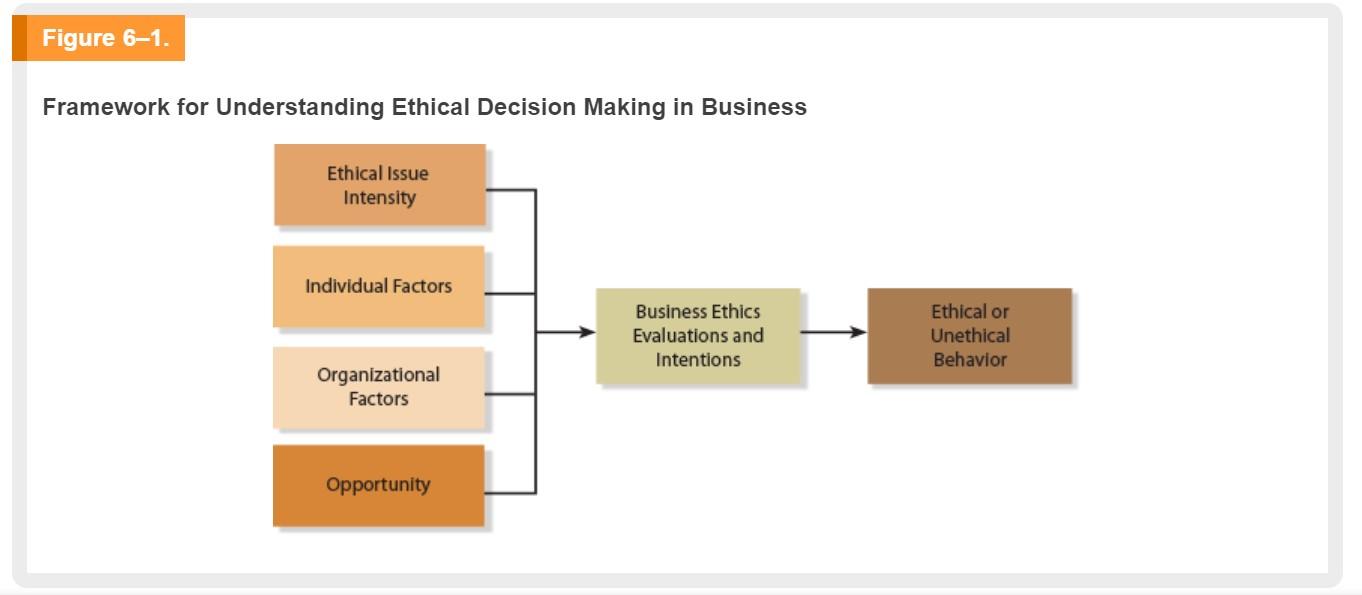

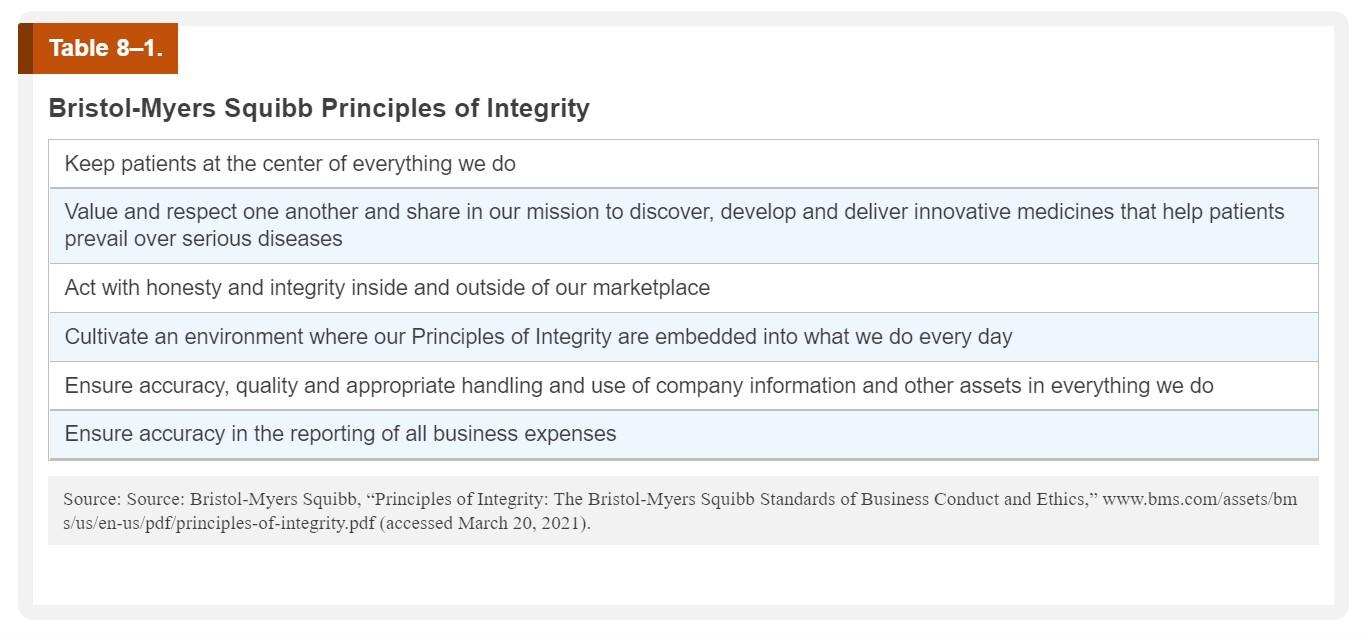

Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response Jay J. Van Bavel 1, Katherine Baicker 2, Paulo S. Boggio 3, Valerio Capraro4, Aleksandra Cichocka 5,6, Mina Cikara 7, Molly J. Crockett 8, Alia J. Crum, Karen M. Douglas 5, James N. Druckman 10, John Drury 11, Oeindrila Dube 2, Naomi Ellemers 12, Eli J. Finkel 13, James H. Fowler 14, Michele Gelfand 15, Shihui Han16, S. Alexander Haslam 17, Jolanda Jetten 18, Shinobu Kitayama 19, Dean Mobbs 20, Lucy E. Napper 21, Dominic J. Packer 22, Gordon Pennycook 23, Ellen Peters 24, Richard E. Petty 25, David G. Rand 26, Stephen D. Reicher 27, Simone Schnall 28,29, Azim Shariff O30, Linda J. Skitka 31, Sandra Susan Smith 32, Cass R. Sunstein 033,NassimTabri34, Joshua A. Tucker 35, Sander van der Linden 28, Paul van Lange 36,KimA. Weeden 37, Michael J. A. Wohl 34, Jamil Zaki', Sean R. Zion 9 and Robb Willer 38 The COVID-19 pandemic represents a massive global health crisis. Because the crisis requires large-scale behaviour change and places significant psychological burdens on individuals, insights from the social and behavioural sciences can be used to help align human behaviour with the recommendations of epidemiologists and public health experts. Here we discuss evidence from a selection of research topics relevant to pandemics, including work on navigating threats, social and cultural influences on behaviour, science communication, moral decision-making, leadership, and stress and coping. In each section, we note the nature and quality of prior research, including uncertainty and unsettled issues. We identify several insights for effective response to the COVID-19 pandemic and highlight important gaps researchers should move quickly to fill in the coming weeks and months. Fig. 1 | infographic depicting a selection of topics from the social and behavioural sciences relevant during a pandemic. Topics covered here indide threat percepticn, social context, science communication, indindual and collective interests, leadership, and stress and coping. impacts. We discuss topics that are broadly relevant to numerous Threat. One of the central emotional responses during a pandemic stages of the current pandemic to help policy-makers, leaders and is fear. Humans, like other animals, possess a set of defensive systhe pablic better undersiand how to manage threats, navigzate differ - tems for combating ecological threats . Negative emotions resultent social and cultural contexts, improve science commanicatioa, ing from threat can be contagions. and fear can make threats align individual and collective interests, employ effective leadership appear more immainent. A meta-analysas fotand that targeting fears and provide social and emotional support (see Fig. I for summary). can be taseful in sonme situations, but not others appealing to fear Tor each area, we highlight relevant insights, thiscuss implications leads people to change their behaviour if they feel capable of dealing for policy makers, leaders and the public (Box 1) and note areas for with the threat, bait leads to defensive reactions when they feel helpfuture research. Due to space constraints, this paper provides a brief summary. greatest behaviour change only when people feel a sense of efficacy, Due to space constraints, this paper provides a brief summary. greatest behaviour change only when people feel a sense of efficacy, of each topic. Research topics discussed here were identified by the whereas strong fear appeals wath lon -efficacy messages prodace the corresponding authors as potentially relevant to pandemic response greatest levels of defensive responses. actions, such as handwashing, face-totaching and self-isclation, the belief that bad things are less likely to befall aneself than others. see ref. '). Furthermore, research on these topics is ongoing and. While optimisam baias may be useful for avoiding negative emotions', in many cases, far from settled. We have hghalighted relevant find- it can lead people to underestimate their libelihood of contract- ings in each area as well as cratical gaps in the literature. Insights ing a disease and to therefore aignore public health warnaings. ings in each area as well as cratical gaps in the literature, Insights ing a disease and to therefore aignore public health warnings. and implications for policy should be interpreted with caution Communication strategies anust strike a balance between breakbecause there is very little published social science research on the ing through optimism bias without indacing excessive feelings of current pandemic. Thus, our discussion often draws from different anxiety and dread. circumstances than the current pandemic (for example, laboratory experiments examiang hypothetical scenarios), and the quality of Emotion and risk perception. Soand health decisions depend an the evidence cited varies substantially (for example, correlational accurate parceptions of the costs and benefits of certain choices for studies vs field experiments; single studies vs systematic reviews of aneself and for society sabstantial evidence). In the sections that follow, we try to describe scanetimes more so than tactual information . Ahn emotional the quality of evidence to facilitate careful, critical engagement by response to a risky satuation can intluence thimking an two stages . readers. We call for the scientific community to mobilize rapidly to Farst, the emotions quality (for example, positive vs negative) focuses produce research to directly inform policy and individual and col- people on congruent information (for example, negative informalective behaviour in response to the pandemic. itself, is then ased to guide judganent at the second stage. For examThreat perception. Historically, infectious diseases have been ple, smokers exposed to more negative emotional health warnings responsible for the greatest human death tolls. For example, the experienced more megative emotion toward warnings and sanoking bubonic plague killed appraximately 25% of the European popula- spent more time examinang warnings and recalled more risks, with bubonic plague killed appraximately 25% of the European popula- spent more time examining warmings and recalled mare risks, with consequences for decision-making and intergroup relations. PERSPECTIVE NATURE HUMAN BEHAVIOUR NATURE HUMAN BEHAVIOUR PERSPECTIVE section, we describe how aspects of the social context, such as people without health insurance may delay or avoid seeking testsocial norms, social inequality, culture and polarization, may help ing or treatment, people who rely on public transportation cannot decision-makers identify risk factors and effectively intervene. always avoid large crowds and low-wage workers are often in occu- Social norms. People's behaviour is influenced by social norms pations (for example, service, retail, deaning, agricultural habour) Social norms. People's behaviour is influenced by social norms where remote work is impossible and employers do not offer paid what they perceive that others are doing or what they think that sick leave". Eeononnic disadvantage is also associated with the others approve or disapprove of . A large literature has distin- pre-existing conditions associated with higher morbidity rates once guished different motives for conformity to norms, including the infected, such as compromised immune systems, diabetes, heart desire to learn from other people and to gain affiliation or social disease and chronjc lang diseases like asthmand andonic obstrucapproval ith. Although people are influenced by normas, their per- tive pulmonary disease. We expect that, as in natural hazards, the ceptions are often inaccurate". For example, people can underesti- economically disadvantaged will be most likely to be exposed to the mate health-promoting behaviours (for example, hand washing-) hazard, most sasceptible to harm from it and most likely to experiin slowing the disease because they an spread positive interven. Culture. A sense of the self as independent versus interdependent tions like hand washing and physical distancing by demonstrating with others is a dimension of cultural variation ". Western Furopean them to a wide range of people". Some research suggrests that a and North American cultures that endorse individualism " are con- larger proportion of interventions cant come not from direct effects sidered independent, whereas most ocher cultures share a stronger on people who receive the intervention, but from indirect effects commitment to collectives such as country, tribe and family and are on their social contacts who copied the behavior". We may there. considered interdependent " While medical policies are different fore leverage the impact of any behavioar change effort by targeting across societies, some differences in the response to the pandernic well-connected individuals and making their behaviour change vis- may be better described as cultural, and many of those have a link- ible and salient to others. ible and salient to others. Another way to leverage the impact of norms falls under the the priority given to obligations and duties in Assan societies may general category of 'mudges', which influence bechaviour through motivate individuals to remain committed to social norms while modification of chooce archistecture (i.e., the contexts in which suppressing personal desires. Second, Assians may more reatily people make decisions). Because people are highly reactive to the recognize unobservable situational influences on viral infection, choices made by cthers, especially trusted others, an understanding like herd immunity. Third, social notms and conventions in North tive impact on behavior . For instance, a message with compelling expressivity of the self (for example, kissing, hugging, direct argusacial norms might say, the overwhelming majority of people in mentation), relative to Asia". This is another reason why interperyour community believe that everyone should stay home. Nudges sonal transmission of the virus could be more likely in independent and normative information can be an alternative to more coercive cultures than in interdependent cultures. means of behavioar change or used to complement regulatory. Another, related, dimension of cultural variance is a societys legal and other imposed policies when widespread changes must "tightness' vs looseness. Research has found that tight cultures, such occurrapidly.pusishmentsfordeviance,whilleloosecultures,suchastheUS,ltalyasthoseofSingapore,lapanandChina,havestrictsocialnormasand Social inequality. Inequalities in access to resources affect not and Brazil, have weaker social norms and are mose permissive only who is at greatest risk of infection, developing symptoms or Tight nations often have extensive historical and ecological threats, saccumbing to the disease, but also who is able to adopt recom- including greater historical prevalence of natural hazards, invasions, mendations to slow the spread of the disease. The homeless can population density and pathogen outbreaks . Froman an evolutionnot sheiter in place " families in housing without ranning water ary perspective, when groups experience collective threats, strict cannot wash their hands frequently "people who are detained by rules may help them to coordinate to survive "Therefore, the or refugee camps) may lackspace to implement physical distancinge accustonned to prioritizing freedom over security may also have PERSPECTIVE NATURE HUMAN BEHAVIOUR information in evidence-based ways that increase understanding are less utilitarian in their ethical decision-making, opting instead and action ". Decades of research has found that, whether recipients for deontic 'do no harm' rules . As such, it may be best to have are motivated to think carefully or not 12, soarces perceived as cred- decissons behind life-for-life trade-offs perceived as systematic ible are more persuasive . The credibility of sources stems from and coming from governmental agencies rather than from physihow trustworthy and expert they are perceived to be 14. Finlisting cians themselves. trusted wices has been shown to make public health messages more effective in changing behaviour during epidemics. During the West Moral decision-making. Moral decision making during a panAfrican Ebola crisis, for example, religious leaders across faiths in demic involves uncertainty. It's not certain whether social interacSierra Leone advocated for practices such as handwashing and safe tions will infect others. People may be less willing to make sacrifices burials. The engagement of the faith-based sector was considered a for others when the benefits are uncertain turning point in the epidemic response "Therefore, finding cred. hypothetical scenarios about deciding whether to go to work while ible soarces for different audiences who are able to share public sick, American and British participants reported they would be hoalth messages might prove effective. Once a credible source is identified, what message should be a co-worker. However, when going to work risked infecting an delivered? Several messaging approaches may be effective, indud- elderly co-worker who would saffer a serious illness, participants ing emphasixing the benefits to the recipient i", focusing on protect- reported they would be more willing to stay home ". Thus, focusing ing others (for example, "wash your hands to protect your parents on worst-case scenarios, even if they are ancertain, may encourage and grandparents appealing to sacial consensus or scientific norms appealing to sacial consensus or scientific norms and/or When people make moral decisions, they often conisider how work best depends on the audience's motivations . Beyond find. actions are judged more harshly than harmful inactions a irend and ing effective messages for attitude change is the issue of inducing causing harm by deviating from the status quo is blamed more than behavioural change. This occurs when people feel confident about harming by default ither. 'Therefore, reframing decisions to carry their attitudes. Methods to increase certainty include helping on with 'business as usual' during a pandemic as active decisions, people feel knowledgeable about their new attitude and making tather than passive or default decisions, may make such behaviours them feel that their new attitude is the 'moral' one to have ". It may less acceptable. therefore be aseful to identify which messages work best on which popalations not only to generate policy suppost but also to ensure Cooperation within graups. Fighting a global pandemic requires individuals' actions needed to combat the spread of the virus. large-scale cocperation. The problem is that, by definition, coop- eration requires people to bear an individual cost to benefit other Aligning individual and collective interests people. In particular, there is a conflict between short-term The behaviour of individuals tiving in communities is regulated self-interest vs longer-term collective interest ". Morecwer, in this by moral norms and values respected and publicly admired, while those who do what is 'wrong' munity, national and international) which can make decisions to are devalued and socially exduded . These mechanisms of social cooperate challenging . From an evolutionary perspective, extending enforcement encourage people to embrace and internalize shared self-interest to protect and promote the welfare of family members guidelines, making them motivated to do what is considered right sboald be a small step, as it increases genetic fitness. Indeed, labowhile avoiding behaviours that seem wrongs, and do not rely on ratory research has focand that people prioritize local over global leyal agreements and formal sanctions . In this section, we con- (or international) interests siskik. One major question, then, is how to social behaviours by individuals and groups. Several techniques, such as sanctioning defectors" or rewarding cooperators", tend to increase coaperative behaviour in laboratory Zero-sum thinking. People often default to thinking that someone experiments using economic games. Providing cues that make the else's gain-erpecially someone from a competing group-necessi- morality of an action salient (such as having people read the Golden tates a loss to themselves, and vice versa . Zero-sum thinking Rule before making a decision or asking them to report what they fits uneasily with the nos-zero-sum nature of pandemic infection, think is the morally right thing to do) bave also been shonen to fits uneasily with the non-zero-sumn nature of pandemic infection, think is the morally right thing to do) have also been shown to where someone else's infection is a threat to oneself and every. increase cooperation one else'. Zero-sum thinking means that while it might be psy. when they believe that others are cooperating . Accordingly, interchologically compelling to hoard protective materials (sanitizer, ventions based on observability and descriptive norms are highly masks, even vaccines) beyond what is necessary, doeng so could be effective at increasing cooperative behaviour in economic games as self-defeating. Given the importance of slowing infections, it may well as in the field. This suggests that leaders and the media can be helpful to make people aware that others' access to preventative promote cooperation by making these behaviours more observable. measures is a benefit to oneself. Whereas reducing infections across the population is Leadership. Crises like the COVID-19 pandemic create an oppornon-zero-sum, the provision of scarce health care resources to tunity for leadership across groaps of varying levels: families, workthe infected does have zero-sum elements. For example, when the places, local communities and nations. Leadership can coordinate number of patients needing ventilators exceeds capacity, health individuals and help them avoid behaviours that are no longer concare providers are often forced to make life-for-life trade-offs. How sidered sacially responsible. In this section, we discuss the roles of well the policies enacted match the local norms can help deternine trust and cornpliance with leaders, effective identity leadership and well the policies enacted match the local norms can belp determine trust and compliance with leaders, effective identity leadership and how mach support they receive. While some people are willing to ences on this preference. Who is perceived to be making those Trust and compliance. During a pandemic, health officials often decisions may also impoct the pablic's and patients trust. In experi need to persuade the population to make a number of behaviour ments, people who make utilitarian judgments about matters of hife changes and follow health policies aimed at containment-e.g-, and death are less trusted . American's trust in medical doctors honouring quarantine or reporting voluntarily for medical testing. remains high , and compared to public health officials, doctors By their nature and the scope of the population, such measures can PERSPECTIVE NATURE HUMAN BEHAVIOUR NATURE HUMAN BEHAVIOUR circumstances, a process that will vary from couple to couple and from partner to partner". The recalibration process involves both (i) lowering broad expectations that the course of true love in the time of COVID-19 will run smoothly while also (ii) sustaining high expectations in those domains where the relationship can deliver in these conditions. Healthy mind-sets. In the face of a global pandemic, avoiding stress altogether is simply not an option. Fortuitously, the past twenty years of research on coping and stress suggest that it's not the type or amount of stress that determines its impact. Rather, mind-sets and situation appraisals about stress can alter its impact 3,23 . For instance, some research finds these mind-sets can increase the possibility of 'stress-related growth; a phenomenon in which stressful experiences serve to increase physiological toughening 2e342, help reorganize our priorities and can help lead to deeper relationships and a greater appreciation for life. Preliminary research suggests that mind-sets about stress can be changed with short and targeted interventions. These interventions do not focus on viewing the stressor (such as the virus) as less of a threat 24. Instead, they invite people to recognize that we tend to stress about things we care deeply about and that we can harness the stress response for positive gain. A number of studies found that inducing more adaptive mind-sets about stress could increase positive emotion, reduce negative health symptoms and boost physiological functioning under acute stress 1 ass. Research is needed to see if adopting these mind-sets can help some people harness the stress during a pandemic for positive growth. Conclusion Over 100 years ago, Science magazine published a paper on lessons from the Spanish Flu pandemic . The paper argued that three main factors stand in the way of prevention: (i) people do not appreciate the risks they run, (ii) it goes against human nature for people to shut themselves up in rigid isolation as a means of protecting others, and (iii) people often unconsciously act as a continuing danger to themselves and others. Our paper provides some insights from the past century of work on related issues in the social and behavioural of the current pandemic. Specifically, we discussed research on threat perception, social context, science communication, aligning individual and collective interests, leadership, and stress and coping. These are a selection of relevant topics, but readers may also be interested in other relevant work, including on psychological reactance 24,24, collective emotions and social media 2y235, and the impact of economic deprivation and unemployment 23,21. Urgent action is needed to mitigate the potentially devastating effects of COVID-19, action that can be supported by the behavioural and social sciences. However, many of the implications outlined here may also be relevant to future pandemics and public health crises. A recent report 2y from the World Health Organization declared that "health communication is seen to have relevance for virtually every aspect of health and well-being, including disease prevention, health promotion and quality of life." Steps of Social Responsibility Philanthropic: "giving back" to society Ethical: following standards of acceptable behavior as judged by stakeholders Legal: abiding by all laws and government regulations Economic: maximizing stakeholder wealth and/or value Source: Adapted from Archie B. Carroll, "The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility: Toward the Moral Management of Organizational Stakeholders," Business Horizons 34 (July-August 1991): 42, Fig. 3. Ethical Decisions Affect Sustainability as a Component of Social Responsibility Examples of Social Responsibility Concerns Source: Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser, "CO2 Emissions," Our World in Data, https://ourworldindata.org/co2-emissions (accessed March 10, 2021). Framework for Understanding Ethical Decision Making in Business Bristol-Myers Squibb Principles of Integrity Keep patients at the center of everything we do Value and respect one another and share in our mission to discover, develop and deliver innovative medicines that help patients prevail over serious diseases Act with honesty and integrity inside and outside of our marketplace Cultivate an environment where our Principles of Integrity are embedded into what we do every day Ensure accuracy, quality and appropriate handling and use of company information and other assets in everything we do Ensure accuracy in the reporting of all business expenses Source: Source: Bristol-Myers Squibb, "Principles of Integrity: The Bristol-Myers Squibb Standards of Business Conduct and Ethics," www.bms.com/assets/bm s/us/en-us/pdf/principles-of-integrity.pdf (accessed March 20, 2021). Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response Jay J. Van Bavel 1, Katherine Baicker 2, Paulo S. Boggio 3, Valerio Capraro4, Aleksandra Cichocka 5,6, Mina Cikara 7, Molly J. Crockett 8, Alia J. Crum, Karen M. Douglas 5, James N. Druckman 10, John Drury 11, Oeindrila Dube 2, Naomi Ellemers 12, Eli J. Finkel 13, James H. Fowler 14, Michele Gelfand 15, Shihui Han16, S. Alexander Haslam 17, Jolanda Jetten 18, Shinobu Kitayama 19, Dean Mobbs 20, Lucy E. Napper 21, Dominic J. Packer 22, Gordon Pennycook 23, Ellen Peters 24, Richard E. Petty 25, David G. Rand 26, Stephen D. Reicher 27, Simone Schnall 28,29, Azim Shariff O30, Linda J. Skitka 31, Sandra Susan Smith 32, Cass R. Sunstein 033,NassimTabri34, Joshua A. Tucker 35, Sander van der Linden 28, Paul van Lange 36,KimA. Weeden 37, Michael J. A. Wohl 34, Jamil Zaki', Sean R. Zion 9 and Robb Willer 38 The COVID-19 pandemic represents a massive global health crisis. Because the crisis requires large-scale behaviour change and places significant psychological burdens on individuals, insights from the social and behavioural sciences can be used to help align human behaviour with the recommendations of epidemiologists and public health experts. Here we discuss evidence from a selection of research topics relevant to pandemics, including work on navigating threats, social and cultural influences on behaviour, science communication, moral decision-making, leadership, and stress and coping. In each section, we note the nature and quality of prior research, including uncertainty and unsettled issues. We identify several insights for effective response to the COVID-19 pandemic and highlight important gaps researchers should move quickly to fill in the coming weeks and months. Fig. 1 | infographic depicting a selection of topics from the social and behavioural sciences relevant during a pandemic. Topics covered here indide threat percepticn, social context, science communication, indindual and collective interests, leadership, and stress and coping. impacts. We discuss topics that are broadly relevant to numerous Threat. One of the central emotional responses during a pandemic stages of the current pandemic to help policy-makers, leaders and is fear. Humans, like other animals, possess a set of defensive systhe pablic better undersiand how to manage threats, navigzate differ - tems for combating ecological threats . Negative emotions resultent social and cultural contexts, improve science commanicatioa, ing from threat can be contagions. and fear can make threats align individual and collective interests, employ effective leadership appear more immainent. A meta-analysas fotand that targeting fears and provide social and emotional support (see Fig. I for summary). can be taseful in sonme situations, but not others appealing to fear Tor each area, we highlight relevant insights, thiscuss implications leads people to change their behaviour if they feel capable of dealing for policy makers, leaders and the public (Box 1) and note areas for with the threat, bait leads to defensive reactions when they feel helpfuture research. Due to space constraints, this paper provides a brief summary. greatest behaviour change only when people feel a sense of efficacy, Due to space constraints, this paper provides a brief summary. greatest behaviour change only when people feel a sense of efficacy, of each topic. Research topics discussed here were identified by the whereas strong fear appeals wath lon -efficacy messages prodace the corresponding authors as potentially relevant to pandemic response greatest levels of defensive responses. actions, such as handwashing, face-totaching and self-isclation, the belief that bad things are less likely to befall aneself than others. see ref. '). Furthermore, research on these topics is ongoing and. While optimisam baias may be useful for avoiding negative emotions', in many cases, far from settled. We have hghalighted relevant find- it can lead people to underestimate their libelihood of contract- ings in each area as well as cratical gaps in the literature. Insights ing a disease and to therefore aignore public health warnaings. ings in each area as well as cratical gaps in the literature, Insights ing a disease and to therefore aignore public health warnings. and implications for policy should be interpreted with caution Communication strategies anust strike a balance between breakbecause there is very little published social science research on the ing through optimism bias without indacing excessive feelings of current pandemic. Thus, our discussion often draws from different anxiety and dread. circumstances than the current pandemic (for example, laboratory experiments examiang hypothetical scenarios), and the quality of Emotion and risk perception. Soand health decisions depend an the evidence cited varies substantially (for example, correlational accurate parceptions of the costs and benefits of certain choices for studies vs field experiments; single studies vs systematic reviews of aneself and for society sabstantial evidence). In the sections that follow, we try to describe scanetimes more so than tactual information . Ahn emotional the quality of evidence to facilitate careful, critical engagement by response to a risky satuation can intluence thimking an two stages . readers. We call for the scientific community to mobilize rapidly to Farst, the emotions quality (for example, positive vs negative) focuses produce research to directly inform policy and individual and col- people on congruent information (for example, negative informalective behaviour in response to the pandemic. itself, is then ased to guide judganent at the second stage. For examThreat perception. Historically, infectious diseases have been ple, smokers exposed to more negative emotional health warnings responsible for the greatest human death tolls. For example, the experienced more megative emotion toward warnings and sanoking bubonic plague killed appraximately 25% of the European popula- spent more time examinang warnings and recalled more risks, with bubonic plague killed appraximately 25% of the European popula- spent more time examining warmings and recalled mare risks, with consequences for decision-making and intergroup relations. PERSPECTIVE NATURE HUMAN BEHAVIOUR NATURE HUMAN BEHAVIOUR PERSPECTIVE section, we describe how aspects of the social context, such as people without health insurance may delay or avoid seeking testsocial norms, social inequality, culture and polarization, may help ing or treatment, people who rely on public transportation cannot decision-makers identify risk factors and effectively intervene. always avoid large crowds and low-wage workers are often in occu- Social norms. People's behaviour is influenced by social norms pations (for example, service, retail, deaning, agricultural habour) Social norms. People's behaviour is influenced by social norms where remote work is impossible and employers do not offer paid what they perceive that others are doing or what they think that sick leave". Eeononnic disadvantage is also associated with the others approve or disapprove of . A large literature has distin- pre-existing conditions associated with higher morbidity rates once guished different motives for conformity to norms, including the infected, such as compromised immune systems, diabetes, heart desire to learn from other people and to gain affiliation or social disease and chronjc lang diseases like asthmand andonic obstrucapproval ith. Although people are influenced by normas, their per- tive pulmonary disease. We expect that, as in natural hazards, the ceptions are often inaccurate". For example, people can underesti- economically disadvantaged will be most likely to be exposed to the mate health-promoting behaviours (for example, hand washing-) hazard, most sasceptible to harm from it and most likely to experiin slowing the disease because they an spread positive interven. Culture. A sense of the self as independent versus interdependent tions like hand washing and physical distancing by demonstrating with others is a dimension of cultural variation ". Western Furopean them to a wide range of people". Some research suggrests that a and North American cultures that endorse individualism " are con- larger proportion of interventions cant come not from direct effects sidered independent, whereas most ocher cultures share a stronger on people who receive the intervention, but from indirect effects commitment to collectives such as country, tribe and family and are on their social contacts who copied the behavior". We may there. considered interdependent " While medical policies are different fore leverage the impact of any behavioar change effort by targeting across societies, some differences in the response to the pandernic well-connected individuals and making their behaviour change vis- may be better described as cultural, and many of those have a link- ible and salient to others. ible and salient to others. Another way to leverage the impact of norms falls under the the priority given to obligations and duties in Assan societies may general category of 'mudges', which influence bechaviour through motivate individuals to remain committed to social norms while modification of chooce archistecture (i.e., the contexts in which suppressing personal desires. Second, Assians may more reatily people make decisions). Because people are highly reactive to the recognize unobservable situational influences on viral infection, choices made by cthers, especially trusted others, an understanding like herd immunity. Third, social notms and conventions in North tive impact on behavior . For instance, a message with compelling expressivity of the self (for example, kissing, hugging, direct argusacial norms might say, the overwhelming majority of people in mentation), relative to Asia". This is another reason why interperyour community believe that everyone should stay home. Nudges sonal transmission of the virus could be more likely in independent and normative information can be an alternative to more coercive cultures than in interdependent cultures. means of behavioar change or used to complement regulatory. Another, related, dimension of cultural variance is a societys legal and other imposed policies when widespread changes must "tightness' vs looseness. Research has found that tight cultures, such occurrapidly.pusishmentsfordeviance,whilleloosecultures,suchastheUS,ltalyasthoseofSingapore,lapanandChina,havestrictsocialnormasand Social inequality. Inequalities in access to resources affect not and Brazil, have weaker social norms and are mose permissive only who is at greatest risk of infection, developing symptoms or Tight nations often have extensive historical and ecological threats, saccumbing to the disease, but also who is able to adopt recom- including greater historical prevalence of natural hazards, invasions, mendations to slow the spread of the disease. The homeless can population density and pathogen outbreaks . Froman an evolutionnot sheiter in place " families in housing without ranning water ary perspective, when groups experience collective threats, strict cannot wash their hands frequently "people who are detained by rules may help them to coordinate to survive "Therefore, the or refugee camps) may lackspace to implement physical distancinge accustonned to prioritizing freedom over security may also have PERSPECTIVE NATURE HUMAN BEHAVIOUR information in evidence-based ways that increase understanding are less utilitarian in their ethical decision-making, opting instead and action ". Decades of research has found that, whether recipients for deontic 'do no harm' rules . As such, it may be best to have are motivated to think carefully or not 12, soarces perceived as cred- decissons behind life-for-life trade-offs perceived as systematic ible are more persuasive . The credibility of sources stems from and coming from governmental agencies rather than from physihow trustworthy and expert they are perceived to be 14. Finlisting cians themselves. trusted wices has been shown to make public health messages more effective in changing behaviour during epidemics. During the West Moral decision-making. Moral decision making during a panAfrican Ebola crisis, for example, religious leaders across faiths in demic involves uncertainty. It's not certain whether social interacSierra Leone advocated for practices such as handwashing and safe tions will infect others. People may be less willing to make sacrifices burials. The engagement of the faith-based sector was considered a for others when the benefits are uncertain turning point in the epidemic response "Therefore, finding cred. hypothetical scenarios about deciding whether to go to work while ible soarces for different audiences who are able to share public sick, American and British participants reported they would be hoalth messages might prove effective. Once a credible source is identified, what message should be a co-worker. However, when going to work risked infecting an delivered? Several messaging approaches may be effective, indud- elderly co-worker who would saffer a serious illness, participants ing emphasixing the benefits to the recipient i", focusing on protect- reported they would be more willing to stay home ". Thus, focusing ing others (for example, "wash your hands to protect your parents on worst-case scenarios, even if they are ancertain, may encourage and grandparents appealing to sacial consensus or scientific norms appealing to sacial consensus or scientific norms and/or When people make moral decisions, they often conisider how work best depends on the audience's motivations . Beyond find. actions are judged more harshly than harmful inactions a irend and ing effective messages for attitude change is the issue of inducing causing harm by deviating from the status quo is blamed more than behavioural change. This occurs when people feel confident about harming by default ither. 'Therefore, reframing decisions to carry their attitudes. Methods to increase certainty include helping on with 'business as usual' during a pandemic as active decisions, people feel knowledgeable about their new attitude and making tather than passive or default decisions, may make such behaviours them feel that their new attitude is the 'moral' one to have ". It may less acceptable. therefore be aseful to identify which messages work best on which popalations not only to generate policy suppost but also to ensure Cooperation within graups. Fighting a global pandemic requires individuals' actions needed to combat the spread of the virus. large-scale cocperation. The problem is that, by definition, coop- eration requires people to bear an individual cost to benefit other Aligning individual and collective interests people. In particular, there is a conflict between short-term The behaviour of individuals tiving in communities is regulated self-interest vs longer-term collective interest ". Morecwer, in this by moral norms and values respected and publicly admired, while those who do what is 'wrong' munity, national and international) which can make decisions to are devalued and socially exduded . These mechanisms of social cooperate challenging . From an evolutionary perspective, extending enforcement encourage people to embrace and internalize shared self-interest to protect and promote the welfare of family members guidelines, making them motivated to do what is considered right sboald be a small step, as it increases genetic fitness. Indeed, labowhile avoiding behaviours that seem wrongs, and do not rely on ratory research has focand that people prioritize local over global leyal agreements and formal sanctions . In this section, we con- (or international) interests siskik. One major question, then, is how to social behaviours by individuals and groups. Several techniques, such as sanctioning defectors" or rewarding cooperators", tend to increase coaperative behaviour in laboratory Zero-sum thinking. People often default to thinking that someone experiments using economic games. Providing cues that make the else's gain-erpecially someone from a competing group-necessi- morality of an action salient (such as having people read the Golden tates a loss to themselves, and vice versa . Zero-sum thinking Rule before making a decision or asking them to report what they fits uneasily with the nos-zero-sum nature of pandemic infection, think is the morally right thing to do) bave also been shonen to fits uneasily with the non-zero-sumn nature of pandemic infection, think is the morally right thing to do) have also been shown to where someone else's infection is a threat to oneself and every. increase cooperation one else'. Zero-sum thinking means that while it might be psy. when they believe that others are cooperating . Accordingly, interchologically compelling to hoard protective materials (sanitizer, ventions based on observability and descriptive norms are highly masks, even vaccines) beyond what is necessary, doeng so could be effective at increasing cooperative behaviour in economic games as self-defeating. Given the importance of slowing infections, it may well as in the field. This suggests that leaders and the media can be helpful to make people aware that others' access to preventative promote cooperation by making these behaviours more observable. measures is a benefit to oneself. Whereas reducing infections across the population is Leadership. Crises like the COVID-19 pandemic create an oppornon-zero-sum, the provision of scarce health care resources to tunity for leadership across groaps of varying levels: families, workthe infected does have zero-sum elements. For example, when the places, local communities and nations. Leadership can coordinate number of patients needing ventilators exceeds capacity, health individuals and help them avoid behaviours that are no longer concare providers are often forced to make life-for-life trade-offs. How sidered sacially responsible. In this section, we discuss the roles of well the policies enacted match the local norms can help deternine trust and cornpliance with leaders, effective identity leadership and well the policies enacted match the local norms can belp determine trust and compliance with leaders, effective identity leadership and how mach support they receive. While some people are willing to ences on this preference. Who is perceived to be making those Trust and compliance. During a pandemic, health officials often decisions may also impoct the pablic's and patients trust. In experi need to persuade the population to make a number of behaviour ments, people who make utilitarian judgments about matters of hife changes and follow health policies aimed at containment-e.g-, and death are less trusted . American's trust in medical doctors honouring quarantine or reporting voluntarily for medical testing. remains high , and compared to public health officials, doctors By their nature and the scope of the population, such measures can PERSPECTIVE NATURE HUMAN BEHAVIOUR NATURE HUMAN BEHAVIOUR circumstances, a process that will vary from couple to couple and from partner to partner". The recalibration process involves both (i) lowering broad expectations that the course of true love in the time of COVID-19 will run smoothly while also (ii) sustaining high expectations in those domains where the relationship can deliver in these conditions. Healthy mind-sets. In the face of a global pandemic, avoiding stress altogether is simply not an option. Fortuitously, the past twenty years of research on coping and stress suggest that it's not the type or amount of stress that determines its impact. Rather, mind-sets and situation appraisals about stress can alter its impact 3,23 . For instance, some research finds these mind-sets can increase the possibility of 'stress-related growth; a phenomenon in which stressful experiences serve to increase physiological toughening 2e342, help reorganize our priorities and can help lead to deeper relationships and a greater appreciation for life. Preliminary research suggests that mind-sets about stress can be changed with short and targeted interventions. These interventions do not focus on viewing the stressor (such as the virus) as less of a threat 24. Instead, they invite people to recognize that we tend to stress about things we care deeply about and that we can harness the stress response for positive gain. A number of studies found that inducing more adaptive mind-sets about stress could increase positive emotion, reduce negative health symptoms and boost physiological functioning under acute stress 1 ass. Research is needed to see if adopting these mind-sets can help some people harness the stress during a pandemic for positive growth. Conclusion Over 100 years ago, Science magazine published a paper on lessons from the Spanish Flu pandemic . The paper argued that three main factors stand in the way of prevention: (i) people do not appreciate the risks they run, (ii) it goes against human nature for people to shut themselves up in rigid isolation as a means of protecting others, and (iii) people often unconsciously act as a continuing danger to themselves and others. Our paper provides some insights from the past century of work on related issues in the social and behavioural of the current pandemic. Specifically, we discussed research on threat perception, social context, science communication, aligning individual and collective interests, leadership, and stress and coping. These are a selection of relevant topics, but readers may also be interested in other relevant work, including on psychological reactance 24,24, collective emotions and social media 2y235, and the impact of economic deprivation and unemployment 23,21. Urgent action is needed to mitigate the potentially devastating effects of COVID-19, action that can be supported by the behavioural and social sciences. However, many of the implications outlined here may also be relevant to future pandemics and public health crises. A recent report 2y from the World Health Organization declared that "health communication is seen to have relevance for virtually every aspect of health and well-being, including disease prevention, health promotion and quality of life." Steps of Social Responsibility Philanthropic: "giving back" to society Ethical: following standards of acceptable behavior as judged by stakeholders Legal: abiding by all laws and government regulations Economic: maximizing stakeholder wealth and/or value Source: Adapted from Archie B. Carroll, "The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility: Toward the Moral Management of Organizational Stakeholders," Business Horizons 34 (July-August 1991): 42, Fig. 3. Ethical Decisions Affect Sustainability as a Component of Social Responsibility Examples of Social Responsibility Concerns Source: Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser, "CO2 Emissions," Our World in Data, https://ourworldindata.org/co2-emissions (accessed March 10, 2021). Framework for Understanding Ethical Decision Making in Business Bristol-Myers Squibb Principles of Integrity Keep patients at the center of everything we do Value and respect one another and share in our mission to discover, develop and deliver innovative medicines that help patients prevail over serious diseases Act with honesty and integrity inside and outside of our marketplace Cultivate an environment where our Principles of Integrity are embedded into what we do every day Ensure accuracy, quality and appropriate handling and use of company information and other assets in everything we do Ensure accuracy in the reporting of all business expenses Source: Source: Bristol-Myers Squibb, "Principles of Integrity: The Bristol-Myers Squibb Standards of Business Conduct and Ethics," www.bms.com/assets/bm s/us/en-us/pdf/principles-of-integrity.pdf (accessed March 20, 2021)

USE THESE TO HELP:

USE THESE TO HELP:

ASSIGNMENT: Answer this ethical problem. Formulate a personal response to the possible decisions or actions a leader in that position would face. Using the theories, models, and processes covered in the class. Describe the rationale behind supporting their position as well as using themes and content discussed in the course. Include an examination into all critiques and opposite viewpoints of such a position, with emphasis directed as to how those viewpoints could emerge through moral reasoning in at least 1200 words.

ASSIGNMENT: Answer this ethical problem. Formulate a personal response to the possible decisions or actions a leader in that position would face. Using the theories, models, and processes covered in the class. Describe the rationale behind supporting their position as well as using themes and content discussed in the course. Include an examination into all critiques and opposite viewpoints of such a position, with emphasis directed as to how those viewpoints could emerge through moral reasoning in at least 1200 words.