Question: what is the case about? what is the problem? how does it get solved? CASE 3-3 Bumper Development Corp. Ltd. v. Commissioner of Police of

what is the case about?

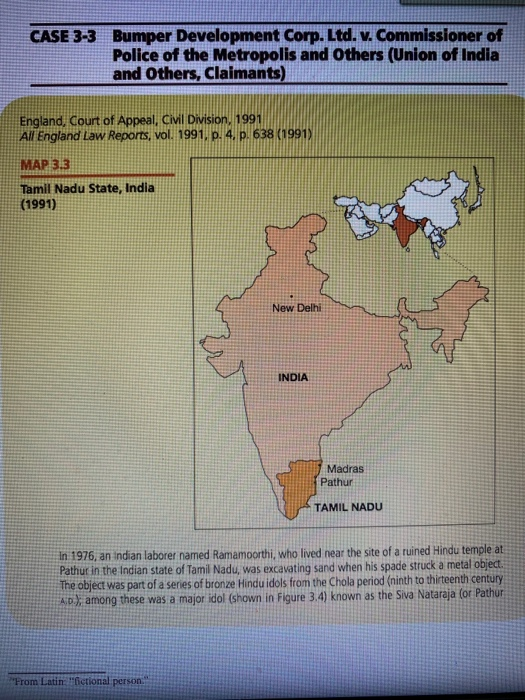

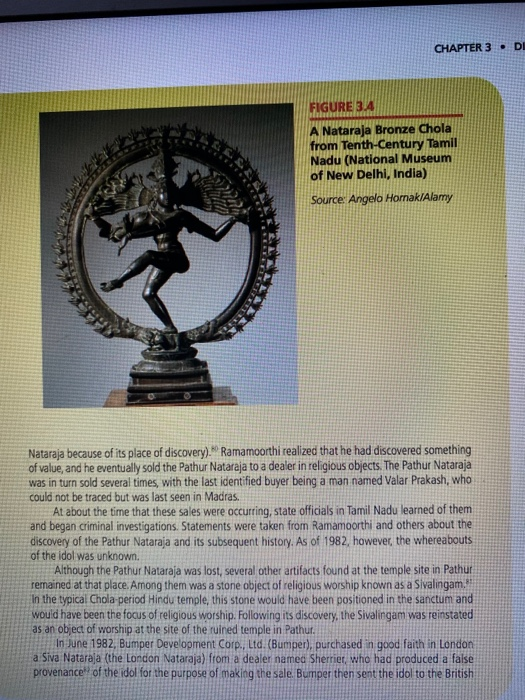

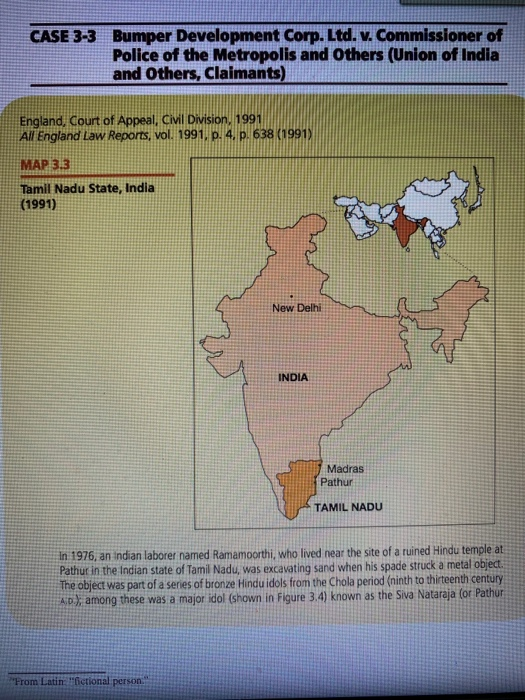

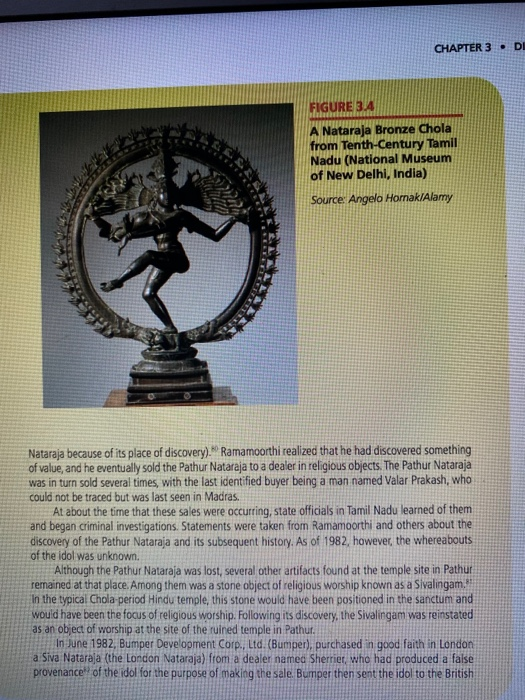

CASE 3-3 Bumper Development Corp. Ltd. v. Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis and Others (Union of India and Others, Claimants) England, Court of Appeal, Civil Division, 1991 All England Law Reports, vol. 1991, p. 4, p. 638 (1991) MAP 313 Tamil Nadu State, India (1991) New Delhi INDIA Madras Pathur TAMIL NADU in 1976, an Indian laborer named Ramamoorthi, who lived near the site of a ruined Hindu temple at Pathur in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu, was excavating sand when his spade struck a metal object. The object was part of a series of bronze Hindu idols from the Chola period (ninth to thirteenth century A.D.), among these was a major idol (shown in Figure 3.4) known as the Siva Nataraja (or Pathur From Latin "fictional person CHAPTER 3. DI FIGURE 3.4 A Nataraja Bronze Chola from Tenth-Century Tamil Nadu (National Museum of New Delhi, India) Source Angelo Hornak/Alamy Nataraja because of its place of discovery). Ramamoorthi realized that he had discovered something of value, and he eventually sold the Pathur Nataraja to a dealer in religious objects. The Pathur Nataraja was in turn sold several times, with the last identified buyer being a man named Valar Prakash, who could not be traced but was last seen in Madras. At about the time that these sales were occurring, state officials in Tamil Nadu learned of them and began Criminal investigations Statements were taken from Ramamoorthi and others about the discovery of the Pathur Nataraja and its subsequent history. As of 1982, however, the whereabouts of the idol was unknown. Although the Pathur Nataraja was lost, several other artifacts found at the temple site in Pathur remained at that place. Among them was a stone object of religious worship known as a Sivalingam in the typical Chola period Hindu temple, this stone would have been positioned in the sanctum and woud have been the focus of religious worship. Following its discovery, the Sivalingam was reinstated as an object of worship at the site of the ruined temple in Pathul. Hinne 1982, Bumper Development Corp., Ltd (Bumper), purchased in good faith in London a Siva Natarala (the London Nataraja) from a dealer named Shemer, who had produced a larse provenance of the idol for the purpose of making the sale. Bumper then sent the idol to the British Museum for appraisal and conservation. While the London Nataraja was at the British Museum, was seized by the London Metropolitan police carne th the British gove us artifacts to their owners. Bumper then commissioner of police of the Metropolis of London and we London Nataraja. araja London and two of ho the trial five daimants intermedio ALATT dy held the ant), the state of Tamil Nadu (the second claim. and an indidual on his own behalt (as the hd commant and on behalf of the temple itself (the fourth claimant). The same been reinstated as an object of worship at the temple site in Pathanter the trial had been later added as an additional claimant (the fifth daimants asserted that they were the rightful ownerse the London Nataraja, which they claimed was one and the same as the Pathur Nataraja. The trial court judge Judge lan Kennedy, held that the evidence of Ramamoorthi and oth ers who had seen the Pathur Nataraja in 1976, as well as expert metallurgical, geological, and entomological evidence, proved that the Pathur Nataraja and the London Nataraja were one and the same. The judge also held that the temple at Pathur and the Sivalingam both had superior title to the Nataraja and that they were entitled to possession of the col Bumper appealed to the Court of Appeal. The Court of Appeal first held that the evidence supported Judge Kennedys conclusion that the London and Pathur Natarajas were the same. It then held that the law of the state of Tamil Nadu regarded the temple at Pathur as a juridical entity that possessed the right to sue and be sued and to own and possess property. The Court of Appeal then considered whether or not English law would look upon the temple as a legal entity Opinion by Lord Justice Purchas Having held that the temple is a legal person under the law of Tamil Nadu acceptable in the courts of that state as a party which, with the third claimant acting as representative, could have sued for the recovery of the Nataraja, we must now decide whether as the judge held, it 15 likewise acceptable in the courts of this country The question whether a foreigner can be a party to proceedings in the English courts is one to be determined by English law (as the lex fom). In the case of an individual no difficulty usually arises. And the same can be said of foreign legal persons which would be recognized as such by our own law, the most obvious example being a foreign trading company. It could not be seriously suggested that such a company could not sue in the English courts to recover property of which it was the owner by the law of the country of its incorporation The novel question which arises is whether a foreign legal person which would not be recognized as a legal person by our own law can sue in the English courts. The particular difficulty arises out of the English law's restriction of legal personality to corporations or the like, that is to say, the personified groups or series of individuals. This insistence on an essentially animate content in a legal person leads to a formidable conceptual difficulty in recognizing as a party entitled to sue in our courts something which on one view is little more than a pile of stones There is an illuminating treatment of legal personality in Salmand on Jurisprudence from wich we take two passage Legal persons, being the arbitrary creations of the law, may be of as many kinds as law pleases. Those which are actually recognized by our own system, however are of comparatively few types. Corporations are undoubtedly legal persons, and new is that registered trade unions and friendly societies are also legal persons though not verbally regarded as corporations. No other legal persons recognized by English law. I however, we take account of other our own, we find that the conception of legal personality is not so limited in its application, and that there are several distint varieties, of which three may be selected for special mention. They are distinguished by reference to the different kinds of things which the law selects for personification. 1. The first class of legal persons consists of corporations, as already defined, namely those which are constituted by the personifikation of arus les of individual The India ak who thus for the corpus of the legal personare terets members The second dass is that in which the compus, or object selected for personificato not GOLD of series of persons but an institution. The law may i le regard a church or a hospital or a University, or a Ibrary as a person. That to It may attribute personality, not to any group of persons connected with the institu! tion, but to the institution itself. Our own law does not, Indeed, so deal with the matter. The person known to the law of England as the University of London is not the institution that goes by that name, but a personified and incorporated aggre- gate of human beings, namely, the chancellor, vice-chancellor fellows, and gradu- ates. It is well to remember however, that notwithstanding this tradition and practice of English law, legal personality is not limited by any logical necessity, or, Indeed, by any obvious requirement of expediency, to the incorporation of bodies of individual persons. Thus Salmond on Jurisprudence recognizes the possibilities which may not be farfetched, of (say) a foreign Roman Catholic cathedral having legal personality under the law of the country where it is situated; and, in order to make the concept more comprehensible, let it be assumed that it is given that personality by legislation specifically empowering it to sue by its proper officer for the protection and recovery of its contents. It would, we think be a strong thing for the English court to refuse the cathedral access simply on the ground that our own law would not recognize a similarly constituted entity as a legal person. The touchstone for determining whether access should be given or refused is the comity of nations, defined by the shorter Oxford English Dictionary as The courteous and friendly understanding by which each nation respects the laws and usages of every other, so far as may be without prejudice to its own nights and interests. Arguing from the example of a Roman Catholic Cathedral and in the belief that no distinction between institutions of the Christian church and those of other major religions would now be generally acceptable, we cannot see that in the circumstances of this case there is any offense to English public policy in allowing a Hindu religious institution to sue in our courts for the recovery of property to which it is entitled by the law of its own country. Indeed we think that public policy would be advantaged. We therefore hold that the temple is acceptable as a party to these proceedings and that it as such entitled to sue for the recovery of the Nataraja For the reasons set out in this judgment we dismiss the appeal on the ground that Judgetan Kennedy correctly decided that the temple had a site to the Nattaja superior to that enjoyed by Bumper Casepoint Alghing and instions do not have sebe besonates ths does not mean that other countries tot recognize istitutons as having separate la personalities. If other countres recognize a s tution such chottemoelas artent with the night to sue or be sued, it is proper for the English Courts t then pressuits brought before the

what is the problem?

how does it get solved?

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

1 Expert Approved Answer

Step: 1 Unlock

Question Has Been Solved by an Expert!

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts

Step: 2 Unlock

Step: 3 Unlock