Question: What was the situation faced by Smithers in this assignment? Dont forget to discuss the environment faced by the company, unit etc (discuss the context).

- What was the situation faced by Smithers in this assignment? Dont forget to discuss the environment faced by the company, unit etc (discuss the context).

Smithers is currently being faced with a dilemma where he is anticipating being laid for from his current job from the role of one of the two instructors for the implementation of a Total Quality program at Sigtek, his current employer. Smithers assumption of being laid off from work is triggered by the recent news of his bosss demotion to an insignificant position in the organization. Smithers believes that it will not be long before he would hear about his demotion or dismissal too.

What went wrong? -

There have been significant factors acting as barriers to this much needed change. For instance, a few managers within the organization showed resistance to change and John had to deal with this by removing these managers from their current roles.

Another major barrier to change was the extreme diversity between the engineering and manufacturing group in the organization. The obvious split or difference between the two groups had created a gulf between these two strategic departments of the same organization which meant that the engineering staff was completely isolated from the rest of the organization. Bringing about change in an organization in terms of creating uniformity through Total Quality program is already faced with diverse cultures that can be rather challenging.

In addition to this, the head of the manufacturing group, Richard Patricof can be identified as a barrier to change as well since rewards resources follow the status quo. His reluctance to accept new management practices and to reward those who adopted them can be identified as a major factor why his sub-ordinates may not be willing to accept the new management practices that Smithers wanted to implement via Total Quality program.

Furthermore, the organizations reluctance to work in teams was another barrier to change. This had been experienced by Smithers several months back when he had tried to create cross-functional teams but the reluctance to attend team meetings and the low attendance during these meetings had shown how teams were not enthusiastic about working in groups.

Drivers to change

While these barriers to change may be there, several factors can be identified which were drivers or forces that initiated this change. While some managers may be resistant to change, there were several others who wanted the change to be implemented as evident by the feedback given by one manager before his resignation. He wanted the fight between the heads of the manufacturing and engineering department to end in order to get further clarity at work.

In addition to this, several other factors were acting as drivers to change. With Sigtek looking for growth in the next five years in the telecommunications industry, change was needed in the organizational culture to bring about uniformity and co-ordination between operations.

With rising competition in the market and the companys products being amongst other commodity products, Sigtek needed differentiation within the organization which could differentiate it from its competitors.

In addition to this, change had become inevitable especially as Sigtek had been bought by another company and the new parent company Telwork had made it clear that it wanted to influence how each of its subsidiaries worked. The fact that Sigtek was not a subsidiary of Telwork made it clear that the parent organization was expecting the company to implement its newly formulated Total Quality Program by the way it was getting it implemented across all subsidiaries. With challenges in the form of a haphazard design process, inadequate documentation and a high employee turnover rate; Sigtek needed to change in order to become eligible enough to come under Telworks corporate umbrella.

2. What forces in and outside the company are likely to push for change? What forces are likely to act as a hindrance to change?

Kotters eight-stage change management process which would be used to evaluate the change management initiative at Sigtek. It can be seen that the implementation of the change followed a reactive approach rather than being a proactive approach for the betterment of the organization. As per Kotters model, the sense of urgency was created after Telwork made it clear that it wanted to influence how its subsidiaries worked (Kotter, 1996). In addition to this, the Total Quality program was also formulated by Telwok. The sense of urgency had already been established after this formulation since Sigtek had to change internally to adapt to Telworks culture.

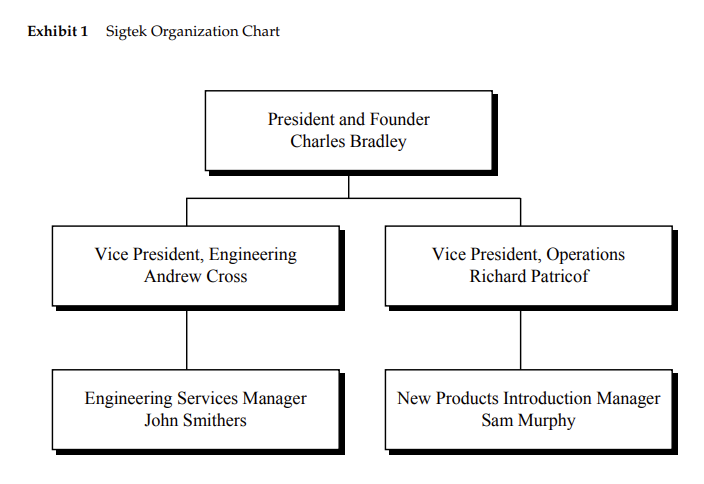

As per Kotters model, the second step involves the creation of the guiding coalition which in simpler terms refers to the creation of a group that has the power to lead the change (Kotter, 1996). In the approach taken at Sigtek, Andrew Crosss decision to make Smithers one of the site instructors for the Total Quality program was a step taken for the creation of a guiding coalition. Not only was Smithers known for his infectious enthusiasm which made him a popular leader, he had an easy egalitarian manner which worked well with his immediate peers and sub-ordinates. Sam Murphy from the manufacturing group was paired with Smithers and both resources showed utmost commitment to the project while setting aside their own differences. The remaining team was largely hand-picked by Patricof.

As per Kotters third step, the instructors for change are supposed to develop a vision and strategy so that the future is different from the past (Kotter, 1996). Apart from being a major decision-making phase, this time phase also requires the leader to motivate people to take action in the right direct in addition to coordinating their actions. This step was followed systematically at Sigtek especially as six Total Quality Goals were established for the program to clearly

3. Chronologically list the activities related to the change process. (Although you do not need to turn the response to this question to me, you will find it impossible to do the case even reasonably well if you do not do this for yourself. Consider each step in the change process as it unfolds to identify where errors were made)

Sigtek, which was founded by three Western Electric veterans 25 years ago, manufactures printed circuit boards for signal handling. Sigtek, a small telecommunication company, sold its products to AT&T and long-distance carriers. In the beginning, the company comprised of 1000 employees with the sales of $60 million. However, the strategy of the company failed to achieve its targets and goals that reduce the companys workforce to 800 employees and sales dropped to $40 million. During this time, another company known as Telwork, a Europe telecommunications company acquired Sigtek. After acquiring the company, Telwork formulated Six Sigma Quality Program to improve product quality, best management practices and create diversification in the company.

According to the case, John Smithers, a dedicated engineering manager was chosen by Sigtek's vice president to become an instructor of the Total Quality Program. However, the company failed to achieve its targets and goals to implement a total quality program effectively. Moreover, John Smithers faced numerous challenges and issues regarding the TQM such as Sigteks engineering and manufacturing divisions, and negative relationship between Richard Patricof. Moreover, the issues include the lack of strong leadership, lack of employees involvement and commitment, high competition, and destructive feedback from the senior managers. Apart from that, untrusting environment led the company to face low morale and unity among departments to achieve the companys goals.

Therefore, it is highly important for the John Smithers and the company to develop a winning strategy, in order to overcome the challenges and issues faced by the company. First, Smithers need to strengthen his position power to improve his ability and skills to bring effective change in the organization. Moreover, he needs to expand his network internally and externally to talk with the quality instructors in other departments as well as gain experience from senior managers. Networking will help Smithers to identify what problems other instructors are facing and how to deal with them. Furthermore, the effective network would give Smithers potential allies because Patricof were to block his efforts. Apart from that, the external networking will help Smithers to increase the information that how to effectively implement the quality change in the company.

Second, the major problem arises is the negative relationship between Smithers and Patricof. Therefore, it is important for Smithers to build a collaborative strategy with Patricof, and improve communication and relationship, in order to identify the mutual interest of the both and work together to achieve the companys goal. However, if the collaborative effort failed, Smithers can initiate different strategy such as hostile or avoiding strategy. But if Patricof refuses to work with him, these strategies would not work for a long-term. Therefore, the collaborative strategy will lead Smithers to achieve its task and implement quality change in the company. Moreover, the Smithers should involve Patricof and other the senior manager in the meeting and the training session of Six Sigma Quality Program. The training will help the managers gain more skills and knowledge regarding the change management in the company. Moreover, training will help to persuade and educate Patricof regarding six sigma and gained his support.

Third, John Smithers should remove the management barriers by developing open communication, diversification, and flexible working environment to encourage both engineering and operations department to work together and achieve the company goals. Moreover, the John should establish a cross-functional team that helps them to communicate effectively and overcome the conflicts among the employees. Furthermore, the HR department involves new trainers from the different department as well as allocates the time; budget and expenses run the TQM program effectively. Fourth, John Smithers should initiate a diversification strategy in the company because this strategy comprises of the many benefits such as innovation, higher-quality employees, lower absenteeism and turnover rate and maximize market share. Therefore, it is highly important for the company to implement the Six Sigma Quality Program, in order to prosper and sustain the growth of the company in the long run.

4. Discuss why things went wrong. Who was responsible? This is an important question make sure to think broadly and consider the roles of various stakeholders in the change process. (75% effort and space)

5. Was Smithers effective? (Discuss. (5%) (what criteria did you use to make this decision)

6. What could Smithers have done differently? As in the past, provide specific actionable recommendations chronologically(20%)

Detailed comments on the above questions.

-We start all our analyses with such considerations: Think about the issues the organization has been facing, and as a second issue, that Smithers is facing. Identify key stakeholders in the change process. Understand their goals and actions.

-Look at Sigtek as the company. Consider forces that are likely to help (or push for) this particular change (the TQM effort) to take place. Then consider forces that are likely to hinder change (be resistant to change). You can consider the broader environment, the HO, people in Sigtek in various departments etc Look at different stakeholders and their positions.

-The question does not ask for your opinion or analysis. All you need to do is to chronologically list out how the change in question (the TQM) was rolled out. This non-evaluative list will help you identify underlying issues at each stage as the change was rolled out.

-This is the most important question to answer and is the heart of the analysis. You have to think about what mistakes were made at various points. Many stakeholders (parties involved or impacted by the change initiative) were involved in the change process. If they made any mistakes identify them. It will be very useful for you to understand how to make successful changes so you can identify errors made by various parties here.

-Take a stand on whether you judge Smithers to be effective (or not). You need to explain the standards by which you judged his effectiveness (or not). Defend your opinion with facts.

-This is also pretty obvious we have done questions like these in all the cases. Support your views.

I need help with 4, 5, and 6. Those answers are based on 1, 2, and 3.

John Smithers It was a few days before Christmas 2001, and a light snow had covered the New England town where John Smithers lived with his wife and two young children. But instead of planning surprises and wrapping presents, Smithers was working on his resume. He had already warned his wife that within weeks he expected to be fired by Sigtek, his employer of three years. His boss and mentor had just been demoted to what appeared to be an extraneous position. He figured it was just a matter of time until his job was taken, too. Eight months earlier, things had looked very different. Smithers's boss, Andrew Cross, had selected him for what appeared to be a challenging and potentially rewarding opportunity: to become one of two site instructors for a Six Sigma Quality program soon to be launched at Sigtek, the telecommunications company where he worked. Not only was Smithers excited at the chance to apply some of the management tenets he believed in so fervently, he also felt that this program could be the key to setting Sigtek on a path toward much needed change. Founded 35 years earlier by three Western Electric veterans, Sigtek manufactured signal-handling equipment, which it sold primarily to AT&T and other long-distance carriers. Sigtek was bought 18 years ago by a large technology company, which had maintained a hands-off management style, and left Sigtek to its own devices. Sigtek was relatively small and it had faced few competitors in its niche. The company had grown steadily, particularly following the 1985 breakup of AT&T and the subsequent opening up of the long-distance market to other competitors. Sigtek's real growth, however, occurred after 1997, when the Internet created a booming demand in telecommunications products, led by companies like Cisco and Lucent. As a result, Sigtek's 1999 sales shot up to more than $600 million, its workforce topped 1,000, and prospects seemed very bright. Many within the company predicted that by 2000 Sigtek would be a $1 billion company. Unfortunately, Sigtek's growth spurt was short-lived. Because of the industry stockpiling in 1999, sales the following year were artificially depressed. Moreover, for the first time, Sigtek began to face serious competition in its marketplace. As the company's products became more of a commodity, customers began to base their buying decisions less on technology and quality instead focusing more on price and delivery time. Moreover, the company's attempt to incorporate a new software suite for signal handling was falling abysmally behind schedule. As a result, by the end of the second quarter 2001, Sigtek's sales had tumbled to about $400 million, and it had trimmed its workforce to 800. Other changes were in the air. In the first quarter of 2001, another company had bought Sigtek. But unlike its former corporate parent, its new owner, Telwork, a $5 billion European telecommunications company, made it clear that it planned to influence how its new subsidiary operated. In February of that year, Telwork began formulating a Six Sigma Quality program, based on the highly acclaimed model at companies like GE and Motorola, which it intended to bring to all its subsidiaries. The goal of the program was not only to improve product quality and encourage better management practices, but also to gather all of the scattered and diverse companies, which Telwork had acquired under a single corporate umbrella. By April 2001, Telwork was ready to begin training instructors from each of its subsidiaries in the Six Sigma Quality program. Smithers Makes a Choice Andrew Cross, Sigtek's vice president of engineering, asked Smithers to become one of two site instructors for the Six Sigma Quality program (see Exhibit 1). Smithers looked up to Cross as a mentor, and the two men had similar ideas about the best way to manage people. Although Sigtek's overall management style could be characterized as autocratic and largely unresponsive to worker concerns, both Smithers and Cross had been working within the engineering side of the business to encourage problem solving and open communication, and to enlist worker participation. Moreover, Smithers had already demonstrated an ability to identify problems within the engineering group and to come up with effective strategies for resolving them. Less than a year earlier, Cross had promoted Smithers to head up engineering services, the group responsible for doing product design work and documentation for manufacturing, and one of Sigtek's more troubled units. As engineering services manager, Smithers had to redefine a haphazard design process, correct inadequate documentation, and cut the highest employee turnover rate in the company. Relying on several articles and books he had read, as well as his own managerial experience at a series of computer startups, Smithers set to work. First, he made several personnel changes, removing or reassigning a few managers who were particularly resistant to change. Next, he gathered group input on how to better define the design process, and then he designed and implemented a new computer integration strategy and reoriented the group to focus on customer-satisfaction goals. After just a few months, the results had already been impressive: the company's design process had become more responsive to customer needs; the designs themselves had fewer errors; the time it took to complete a design had been cut in half; and the employee attrition rate, which had been quite high, had dramatically declined. In addition, several of Smithers's peers remarked that he had an infectious enthusiasm that made him a popular leader. Smithers believed that his easy, egalitarian manner had worked well with both his immediate peers and subordinates, as well as the typically middle-aged women who worked on the line assembling Sigtek's products. In reflecting on why he was asked to be an instructor, Smithers believed that Cross was determined to get a strong engineering representative in the Six Sigma Quality program. Although many companies experienced a natural split between their engineering groups and the rest of their operations, Smithers felt that the separation was carried to an extreme at Sigtek. Indeed, Smithers believed that the corporate culture was best characterized by the extreme polarity that existed between the two sides of the organization: engineering and manufacturing operations. Sigtek's engineering staff was isolated in its own building, separated from the rest of the operations by a long hallway, and this physical separation seemed symbolic of the deep organizational gulf dividing the two sides. This antipathy between engineering and operations had existed for many years. But Smithers thought that the current heads of the two groups-Cross, and his counterpart in operations, Richard Patricofseemed particularly ill matched. From Smithers's perspective, Cross appeared committed to bringing in new blood and new management practices, while Patricof seemed to lean more toward style and less toward substantive results. Smithers's perception was that Patricof rewarded those who parroted his beliefs and those who rarely questioned the status quo. Since both Cross and Patricof were each responsible for selecting one instructor for the program, Cross had told Smithers that he needed to put one of his best managers forward for the job, and thus had nominated Smithers. Charles Bradley, Sigtek's largely absentee president and the last remaining member of its founding team, had chosen Patricof as Sigtek's representative on the Telwork corporate Six Sigma Quality Team. This team served as an advisory group for the Six Sigma Quality program and was made up of representatives from corporate headquarters and each of Telwork's subsidiaries. Cross told Smithers that this had already given Patricof an unfair opportunity to use the quality program for his own personal advancement. Cross felt that Smithers would bring some important balance to the process. Smithers accepted the teaching post with some ambivalence. When I first started, I said to him, I will do it if I don't have to lie," Smithers recalled. "If I lie, I stop doing it.' I was skeptical about our ability to effect change." A number of factors lay behind Smithers's uneasiness. For one thing he was afraid that a program of this sort might raise workers' expectations too high. He had seen evidence already of how resistant the Sigtek culture could be to change. In particular, he feared that the company's rift between engineering and manufacturing operations would present a formidable barrier to any change program which required that the entire organization rally and unite behind a single cause. Moreover, although he had succeeded in attaining cooperation within his own engineering design department, Smithers had already experienced the frustrations of attempting to get this kind of cooperation on a company wide scale. Several months earlier, when working on upgrading the engineering design process, Smithers had tried to create a cross-functional team to identify ways in which his group could better serve and work with Sigtek's other operations. But the "team" concept had fizzled out when his peers from other areas had either come to meetings reluctantly, or simply did not bother to attend. Smithers felt that another drawback of the teaching post was that he would be paired as an instructor with Sam Murphy from the operations side with whom he had already had several run-ins, and for whom he had very little respect and saw as a "fire fighter-type manager." "It was a joke," Smithers laughed. "It was like they were saying oil and water have been chosen to do this training together." Despite these fears, Smithers retained some of his enthusiasm. Secretly, he hoped that the quality program would prove to be the pivotal change, which Sigtek needed. I saw it as the last possible opportunity to alter the organization in a way that I had been trying to do in my own engineering services group," he explained. "I told my own people to just wait. If I can get this quality stuff going, we will all have a common battle cry." In fact, Smithers was becoming increasingly convinced that unless Sigtek embraced some kind of change program, its days were numbered. He was certain that the antagonism between engineering and operations, which had flourished under the weak leadership of Bradley, was not only making it impossible for the organization to operate in an efficient and effective way, it was literally threatening to tear the organization in two. "There was one operations manager there who told me right before he resigned that he just wished the fight between Cross and Patricof would end," Smithers confided. "Then at least we would know who had won, and what to do." During May and June, Smithers and Murphy joined 10 other instructors from Telwork's other subsidiaries for three weeks of training, designed to familiarize them with the Six Sigma program materials and to teach them communication and presentation skills. The training was exciting; however, there were still reminders of the obstacles he faced. For example, Smithers and Murphy both tried to get seats apart from each other when they flew to these off-site sessions. Still, Smithers felt encouraged by the caliber of the program. I was impressed with the materials," he recalled. Because I had been doing a lot of reading already, this incorporated most of the stuff I had figured out." Specifically, the program focused on raising employee awareness of the following Six Sigma Goals: 1. to provide product and service quality better than all competitors; 2. to be the lowest-cost quality producer; 3. to relentlessly pursue quality improvement until Six Sigma levels were achieved to manage through leadership; 5. to personally involve all employees through participative activity; 6. to be comprised of employees who approach the job fearlessly. With these goals in place, the program literature promised, Telwork would be well on its way to becoming a market leader in its chosen niche within the telecommunications industry. These concepts were not new to Smithers. But apparently, they were new to Richard Patricof, Sigtek's representative to the corporate Six Sigma Team, who had attended some of the same meetings. "When I came back from my first introduction to this stuff, Patricof said, 'Boy, that was great. You learn a lot of new stuff,"" Smithers recounted. "Because I had heard most of it before, I said, No, I didn't really learn a lot of new things, I learned some new terminology. And it was very exciting to learn the terminology that goes along with the management style I have been trying to practice." Smithers and Murphy weren't scheduled to start training at Sigtek until September. In the meantime, Telwork sent a team of corporate trainers to Sigtek in July to present the Six Sigma module to the company's senior and middle managers. Altogether, about 25 managers attended the 2-day, 16-hour programthe same program that Smithers and Murphy would later be presenting to the rest of the organization. "There were two purposes here," Smithers explained: "To help make our job as instructors easier, and to give management time to think about the magnitude of the change that would be happening after we started to give it to the ranks." Smithers found the response to the program deeply disturbing. He still remembered the uneasy sensation that gripped him as the presentation to the managers had ended. This was the first time our entire senior management had seen the program," he recalled, "and there were no questions during the entire presentation. What scared me the most was thinking that nobody cares. Or that nobody comprehends. Or that they are scared out of their boots. He added: They had told us in class that when we presented the material, we would have (1) champions; (2) people we could convert; and (3) 'no-sales' (people we couldn't reach). What I realized as I looked around was that there were a couple of champions and possibly no converts." " Before starting the general training, Smithers and Murphy tried to lay the groundwork necessary to support the ambitious program they were about to present. They met with the site Six Sigma Team, a cross-functional group of Sigtek managers largely hand-picked by Patricof, which was intended to serve as a sort of steering committee-establishing guidelines and in other ways helping to implement the Six Sigma program. In addition, they struggled to pull together their presentations. During this time, the two instructors' mutual respect began to grow. Smithers realized that both of them were committed to the program, and they tried to put their differences aside for the good of the company. But as the quality program took more and more time, Smithers found that his own department was starting to suffer from his frequent absences. There were personnel issues to resolve, for example. As his attention was pulled in two directions at once, both he and Murphy agreed that they needed an extra week to be ready for the September launch of the program. But when they asked Patricof, as the corporate quality representative, for a one-week extension, he turned them down. "I'm not even going to judge whether it was Patricof not wanting to wait," Smithers said, "or corporate telling him to get moving." Six Sigma Training Begins With a little scrambling, Smithers and Murphy got the training underway. In September, they together presented three two-day classes to groups of about 25 employees who were usually all at the same hierarchical level. According to me, what they were supposed to get out of this was a belief in a new system of management and a new work environment," Smithers said. "We laid out specific things that people could do, and things they should see happening." Conducting these sessions revived some of Smithers' hope and optimism. For one thing, he liked the materials he was using. The format was not entirely rigid which allowed the instructors to emphasize the points they found most relevant. Moreover, the program's mix of workshops, videos, and other multimedia presentations was entertaining, both for the instructors and the audience. "I felt I had the tools I needed," Smithers mused. I felt I could make the glaring deficiencies of the organization apparent to everybody." But even better than that, Smithers felt that the line workers who attended the programs were buying into the Six Sigma concept wholeheartedly. Smithers saw that employees were coming to the workshops with lists of examples of how things weren't working according to a Six Sigma plan, and with ideas about how to fix them. "What was intriguing was the ability of the line workers to understand what we were talking about and the inability of most of those above them to understand," he exclaimed. These were people who in some cases did not have a full high school education, but they picked it up in a snap. For them what it came down to was common sense and just treating people right. He added: "If I could have taken 95 percent of those line workers and gone off and started another company that day, in terms of problem solving, in terms of productivity, and in terms of motivation, we would have been in good shape." The Unraveling Begins It wasn't long, however, before Smithers' burst of optimism began to fade. Within weeks of the training kickoff, his original fear of being put in the position of "disseminating lies" began to weigh heavily on his mind. I am pretty good at pumping up a crowd," he explained, and I could see that with these tools and with my enthusiasm for it, the first thing you are going to do is heighten expectations way beyond reality. The workers would go back to their real world and not only would nothing be changed, they'd see that they couldn't change it." In fact, Smithers claimed, this is exactly what began to happen. One of the easily fixable" problems that a worker had submitted at one of the first Six Sigma workshops was the dilemma of the "bouncing boards. Specifically, the way the assembly process was set up, workers would place small components on a printed circuit board, stack the boards on carts, and then wheel them across the room to where other workers would solder the components in place. But because many of the carts had hard metal wheels, when they rolled across cracks in the floors, the boards would bounce and send the unsoldered components flying like pieces of popcorn. This was just the sort of manageable problem Smithers wanted to attack. He led the workshop participants in finding acceptable solutionseither to have the maintenance people build new carts out of spare parts, or to order new ones with soft rubber wheelsand encouraged them to take the ideas back to the floor supervisors for action. But the problem didn't go away. "Three or four weeks would go by and I'd have a new class," Smithers recounted. I'd say, "Give me an example of something that can be fixed,' and they'd say, Bouncing boards! I was incredulous." He added: "At some point, the people coming in knew it had been a topic in the past, and I was losing credibility." Smithers finally asked Murphy to look into the situation, since it was on the operations side of the business, just as new carts arrived. Although the problem was eventually resolved, Smithers never forgave the damage done to his own credibility by the long waiting period. "Patricof was always telling us to get known wins to go for the casy wins," he grumbled. "Yet this was the simplest problem, and it wasn't getting fixed. I didn't see it as a success, because I saw the bureaucratic structure and the value system behind it all. He added: "Management just had this attitude like, I'm working on problems that are more serious than the components bouncing out of the boards."" Smithers also found several other incidents disturbing. One woman in an early workshop complained that for years she had been banging her knee on a metal plug receptacle, which stuck out from the wall under her particular workstation. After coaching her in how to raise this issue at her group's weekly quality meeting, the woman left happy. But when Smithers went out on the floor the following week to touch bases with the workshop participants, he recalled the woman hissed at him, John Smithers, you speak with a forked tongue." Not only had she been unable to air her complaint with her floor supervisor, the woman also reported that the supervisor had peremptorily declared that she had no time and no budget for weekly meetings. Smithers, unable to resolve the matter with either the supervisor or her boss, finally appealed to accounting, determined that the meetinga supposed "corporate mandate" of the quality program, would take place. "I went over to accounting and I said, 'I want to charge an hour meeting to my group because that group over in operations can't pay for it, and those people are going to have a meeting!'" he recounted. "The person in accounting liked me, and she understood what I was trying to do, but she told me she could not do it that way." He added: "It must have taken a month for that meeting to happen, and another month for that socket to get fixed. That was a success, but look at the effort." As a result of such incidents, Smithers doubted whether any of the company's senior managers (including Patricof, Sigtek's Six Sigma liaison to corporate), were committed to the changes they were preaching. Although the training manual stressed the importance of encouraging worker participation and input, employees who asked for changeslike the woman who complained about the plug receptaclewere usually ignored or, worse yet, viewed as troublemakers. Senior management knew how to do everything better than the person working on the floor," Smithers grumbled. "There was a autocratic, untrusting environment, especially in manufacturing. I kept hearing things along the lines, of 'Gee, John, real men don't manage that way." In addition, Smithers also suspected that some managers were trying to push through their own agendas by cloaking them in the mantle of the new quality program. "People would say, 'Well, I'm trying to do Six Sigma Quality,'" he said, and if you don't agree with me, you're not for Six Sigma Quality.'" As Smithers and Murphy continued training people on into October, their sense of operating in a vacuum deepened. Smithers felt, for example, that the site Quality Team, which was supposed to coordinate and facilitate Six Sigma efforts at the facility, was so quiet that most people were unaware of its existence. There was no visibility," Smithers contended. No memos, no newsletters. They made promises to us about meeting with people throughout the company but did not keep them." Instead of getting actively involved in the implementation of the program, Smithers felt that the team wasted its time on inconsequential bureaucratic decisions. "The guy in charge of the reward and recognition program spent months trying to write a formula for how many 'Atta boys' it takes to get a key chain, and how many for a coffee mug," he exclaimed. "All that these people knew about management was how to fill out time cards." Smithers added: "That's the way Sigtek had trained them-it wasn't their fault." As obstacles to the Six Sigma program continued to mount, Smithers voiced his frustrations not only to his boss, but also to his staff of five, and to a number of other direct reports. Although publicly he kept up a facade of optimism, behind closed doors, he confessed his doubts about the program, and his misgivings about Patricof. "I'm a pretty open person," Smithers explained. "Perhaps I wasn't as good a buffer as I could have been. But that's what makes me credible." He added: "I am lucky, because as a person, I can manage in a way that is consistent with my personality and get things done while treating people nicely. Richard Patricof wanted to be the same kind of person, but in my estimation, the required results were missing. He spent so much energy on style that things like the carts in manufacturing wouldn't get fixed." Pulling Back By early November, Smithers was ready to put the Six Sigma training process on hold. It wasn't that he felt the program had been completely futile. I could still really get my energy level up during those classes and believe that we were effecting change, because I couldn't have gotten up in the morning if I didn't," he reflected. "If I could change those bouncing carts in three months, versus them never being changed, I could do something." Nevertheless, Smithers felt that the visible successes had been far too small. In order to build the commitment and enthusiasm necessary to mobilize the workforce, he needed some big wins- examples of real changes that the Six Sigma program had achieved. Not only had there been no such big wins, company morale was dipping lower than ever. Sigtek appeared to be headed for its first loss. Moreover, in the seven months since Smithers had first agreed to be a quality instructor, there had been four rounds of layoffs at the company, each more severe than the last. Convinced of the need for a reassessment, Smithers and Murphy asked for a temporary break in the classes. Once again, Patricof refused their request. This was clearly not an option with Patricof," Smithers said. "He was obviously thinking, Corporate has a schedule, and we will not be the slowest ones.' It was all keeping face." Smithers kept teaching, but his dissatisfaction grew. The Six Sigma program itself, which had seemed to him to be so impressive and thorough at first, now began to seem inflated and over ambitious for Sigtek's needs. "Instead of being too little, too late, it was way too much, too late," he declared. "The more I dealt with it, the more I realized it was a cookie cutter program, it was dogmatic, and it was way too much." Smithers also began to question Telwork's motives in imposing such a program on all of its subsidiaries, regardless of their businesses and needs. Word was going around the plant that Telwork was expecting the same inventory practices and turns from Sigtek that it did from its fiber optic cable companiesbusinesses that made a straight commodity product. In addition, Telwork didn't seem to understand that a major corporate change typically takes years. "Corporate was giving us such a mixed message," he complained. "They put all this money into a Six Sigma Quality program and in the end, all Patricof was supposed to give them was weekly numbers, and I don't mean quality numbers." He added: "The joke was that short-term planning under Telwork is one week, and long-term planning is two weeks. The kinds of numbers we were supposed to give them were physically impossible." In the midst of all these doubts, Telwork orchestrated a major management change, which, to Smithers, at least, formalized a power structure that had already existed in practice for months. Charles Bradley, the founder and president, was terminated, and Patricofwho in Smithers' eyes embodied all that was wrong with Sigtek's leadershipwas named the new general manager of Sigtek. Patricof took two actions immediately after becoming general manager. First, he told Smithers and Murphy that they no longer needed to attend the site Six Sigma Team meetings, since these were his responsibility. Second, Patricof, in effect, demoted Smithers' boss and mentor, Cross, by naming a second director of engineering and putting Cross in charge of a single, faltering product line. At this point, Smithers concluded, "the writing was on the wall. I was lying," he stated bluntly, referring back to his early fear that the teaching job might force him to offer false hopes and expectations to employees. "I asked to stop teaching. My public justification was that my job needed me full time." Smithers made this decision even though he knew it threatened his career. "I realized I was committing suicide," he recalled. As soon as I got off that teaching schedule, they could lay me off any time." But despite the palpable dislike that Smithers believed existed between himself and Patricof, the new general manager asked him to keep teaching. "He told me I was too valuable and had too many followers to lose," Smithers recounted. I think I had him in a position he didn't want to be in because to some people I was even more credible than he was." Although, to others, Patricof's request might have seemed like an endorsement, to Smithers, it appeared that the end was in sight. "By Christmas, there were no knowiis," he lamented. "Bradley was gone. Patricof had won. I started doing my resume." As he looked back over the preceding eight months, Smithers was filled with a sense of profound regret. I got into an organization where I thought I could accomplish something, I found a good mentor, but it didn't work," he remembered thinking. "Could I have done something different? That's still a hard question for me to answer. Exhibit 1 Sigtek Organization Chart President and Founder Charles Bradley Vice President, Engineering Andrew Cross Vice President, Operations Richard Patricof Engineering Services Manager John Smithers New Products Introduction Manager Sam MurphyStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts