Question: Whole Organizational Design Intervention - Using Galbraith's STAR model, evaluate what you know about the current situation in this organization. Complete each of the categories

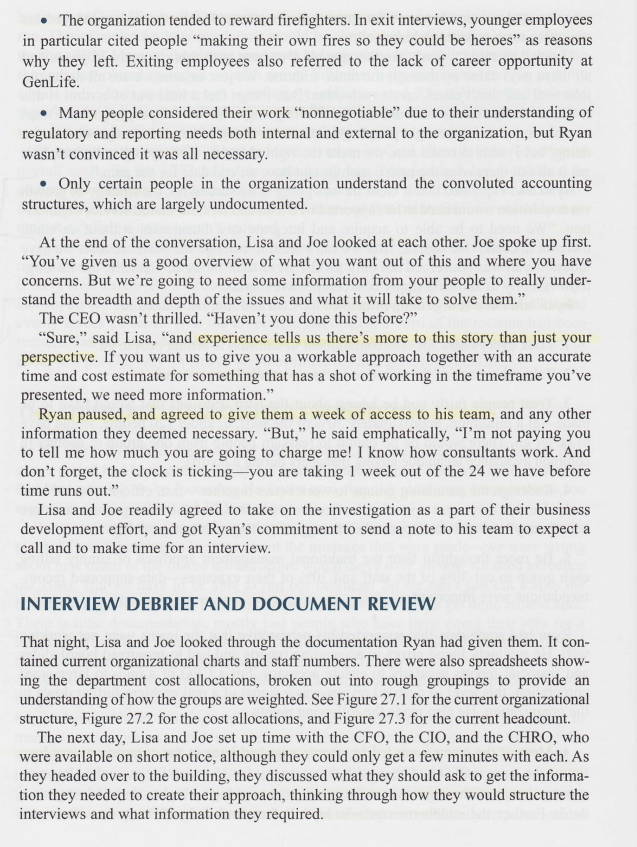

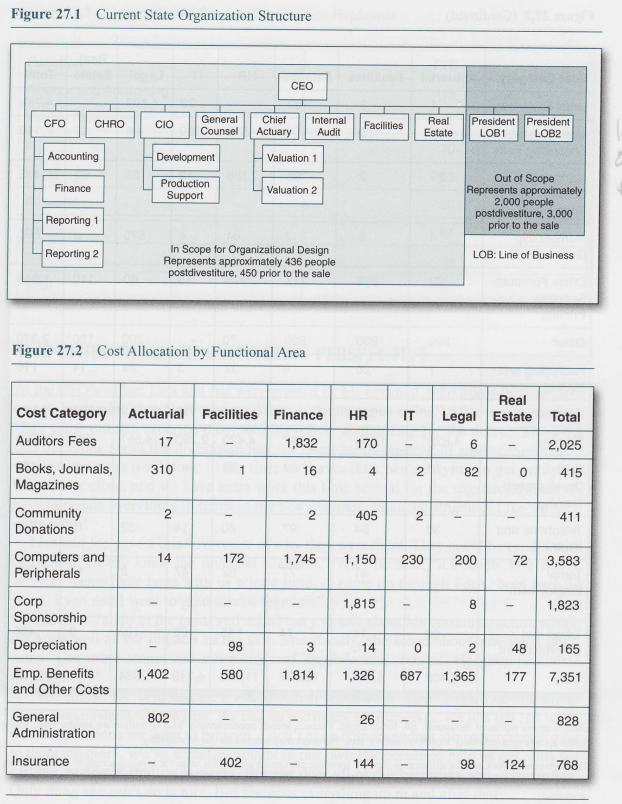

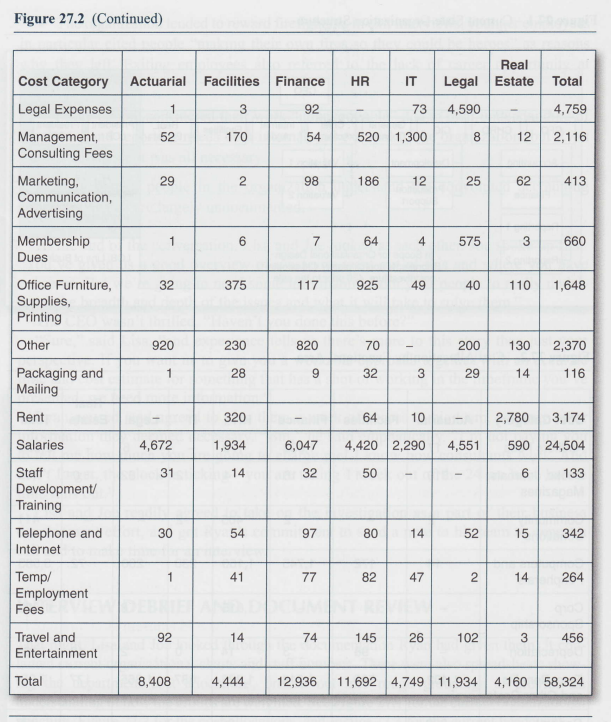

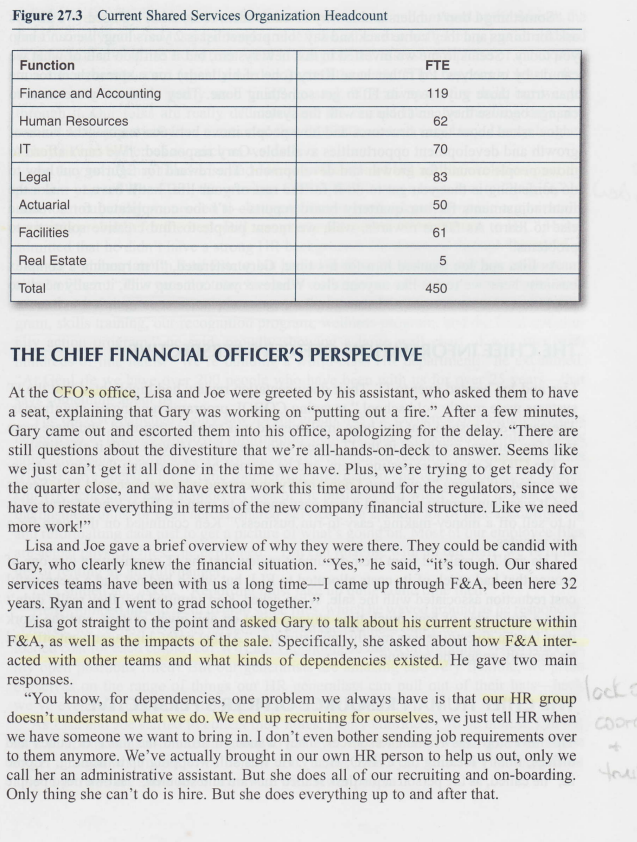

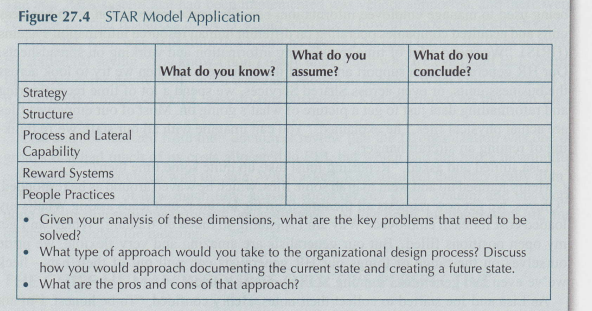

Whole Organizational Design Intervention - Using Galbraith's STAR model, evaluate what you know about the current situation in this organization. Complete each of the categories in Figure 27.4 at the end of the case. - Given your analysis through the STAR Model, what are the key problems/issues that need to be addressed? - Which organizational interventions(s) based on course material would you recommend addressing the key problems/issues? What are the pros and cons of each intervention that you recommend? G enLife, Inc. was an established multinational insurance company, was well-known in the area, and employed approximately 3,000 people, many locally. They had grown through an acquisition strategy over the past 10 to 15 years. They tended to acquire and absorb rather than leave businesses to run independently, but they often struggled to integrate systems and operations. In a recent effort to "get smaller to grow bigger," GenLife had sold off a part of its business that dealt specifically with executive life insurance (ELI) and approximately a third of its employees either joined the acquiring company, ExecuLife, or were let go, depending on their job functions. Most of these jobs were sales related, directly tied to the ELI business. Approximately a third of GenLife's revenue went to ExecuLife with the sale, and it was anticipated GenLife expenses would reduce by approximately a third as well. However, just 3 months after the sale, GenLife CEO Ryan Bind was finding that very little had changed in the cost structure of GenLife. Apparently ELI hadn't used corporate shared services very much, so there were still high support needs postsale. The remaining 256 PART II. CASES IN ORGANIZATION DEVELOPMENT INTERVENTIONS business of GenLife was left supporting the company, and it was simply too expensive to run. The estimates for how much cost would be eliminated at divestiture were off by as much as 30%. Many of the shared processes to support the remaining business were done through convoluted spreadsheets with arcane links that were understood only in parts by certain individuals and processes were largely undocumented. The company had invested significantly in a centralized system to assist in enterprise management processes, but very few people used it, preferring their manual processes. In summary, the sale of ELI had reduced revenue for GenLife with little reduction in overall costs. So the CEO called in consultants Lisa Mendez and Joe Henderson to address the situation. Drastic measures were required in the next 6 months to avoid serious financial damage. Six months was a hard date - at that point, GenLife would be running at a deficit if costs weren't reduced. The company's infrastructure was provided via a shared services structure for internal operations, including Human Resources (HR), Legal, Facilities, Finance and Accounting (F\&A), Real Estate (RE), Actuary, and Information Technology (IT). These seven groups had supported both the remaining and the sold businesses, and costs had been allocated evenly across all areas. With the divestiture out of ELI, a third of the revenue had been reduced, but the shared services organization had not shrunk in a similar way. In fact, of about 450 people, only 14 shared services resources had gone to ExecuLife. THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER'S PERSPECTIVE As the CEO, Ryan had approved the sale of the ELI business, and during the due diligence period had been convinced by his team that the business case was solid; however, that was proving to be incorrect. He knew now that the remaining business was too expensive to run without the ELI revenue. Ryan presented the financial situation to Lisa and Joe as both fact and history-as he put it, "There's nothing to be done about the mistakes that were made-we were wrong about how much of the shared infrastructure would move over, so now we need to reduce our costs. But we have to be able to run our business! So we can't just cut across the board and hope for the best. Plus, no one really knows how things get done around here. There is little documentation, mostly just people who have been doing their jobs for a long time. If we lose them, we'll go off the rails. So we need to do this thoughtfully and take advantage of the opportunity to put some things to right." Ryan explained his suspicion that the organization, which had grown haphazardly over the years, was not serving the real needs of the business. According to him, at an executive and senior level, some groups had been created just to give people something to manage as they got promoted, not necessarily because it made good sense. Some of the managers were better at lobbying for staff and funding and were providing "Cadillac" levels of service while others were bare-bones for no logical reason. The processes being used within the groups were, he felt, convoluted and based on legacy assumptions about what was necessary. There was no clear definition of what was minimally required versus what was "above and beyond" for running the business. Finally, he was convinced his executive team wasn't working well. "Look," he said, "I don't like this one bit. I've been with this company 35 years, and all these guys came up through the ranks with me. We just assume we are all doing our jobs well and don't check up on each other. But, things feel a little out of control if this is what it really costs to run our business. We're going to have to let people go, but I want to make sure we let the right people go, and we're going to have to change what we're doing, but I want to make sure we make the right changes. If it's going to be bad, let's get it all out there over the next 6 months and have an end date for the pain." Ryan also explained that if GenLife was going to be successful, the strategy of growth via acquisition would need to be supported by a lean and flexible shared service organization. "We need to be able to acquire and integrate new businesses without an equal increase in costs," He sighed. "But we can't seem to manage the business costs we have today." Ryan was concerned not only for the short-term future of GenLife, but its longterm viability in an increasingly cost competitive market. Ryan laid out a few guiding principles for Lisa and Joe. He wanted to: 1. Look everywhere for cost containment in addition to letting people go. 2. Take advantage of the situation to "get a handle" on processes. 3. Treat people fairly and be honest about the hard decisions that would have to be made-at a minimum, approximately 30% of the staff, or about 120 people, would have to be let go. There would be no option to reassign people from one group to another (a common avoidance technique among managers during a layoff). 4. Redesign the remaining groups to work better together-fast, efficient, and able to scale. He felt they were operating ineffectively as silos, and the management structure was "heavy" and did not support the strategy of getting small to grow big. 5. Be more thoughtful than the traditional management approach of simply telling each group to cut 30% of the staff and 30% of their expenses-data-supported recommendations were important. Ryan had some data that supported his perspective that the teams were not working well. He routinely found errors in accounting reports and had to proofread board slides and financial reports regularly to ensure accuracy. For a CEO of a mid- to large-sized corporation, this level of detailed review was a signal of a real problem further down in the organization. He also made the following points. - Most of the teams were led by people who had been in the company a very long time-the current CFO had been with the company for 35 years, for example. However, at entry levels in the organization, turnover was very high-higher than industry standards. Further, the middle management layer had expanded significantly over time. - The organization tended to reward firefighters. In exit interviews, younger employees in particular cited people "making their own fires so they could be heroes" as reasons why they left. Exiting employees also referred to the lack of career opportunity at GenLife. - Many people considered their work "nonnegotiable" due to their understanding of regulatory and reporting needs both internal and external to the organization, but Ryan wasn't convinced it was all necessary. - Only certain people in the organization understand the convoluted accounting structures, which are largely undocumented. At the end of the conversation, Lisa and Joe looked at each other. Joe spoke up first. "You've given us a good overview of what you want out of this and where you have concerns. But we're going to need some information from your people to really understand the breadth and depth of the issues and what it will take to solve them." The CEO wasn't thrilled. "Haven't you done this before?" "Sure," said Lisa, "and experience tells us there's more to this story than just your perspective. If you want us to give you a workable approach together with an accurate time and cost estimate for something that has a shot of working in the timeframe you've presented, we need more information." Ryan paused, and agreed to give them a week of access to his team, and any other information they deemed necessary. "But," he said emphatically, "I'm not paying you to tell me how much you are going to charge me! I know how consultants work. And don't forget, the clock is ticking-you are taking 1 week out of the 24 we have before time runs out." Lisa and Joe readily agreed to take on the investigation as a part of their business development effort, and got Ryan's commitment to send a note to his team to expect a call and to make time for an interview. INTERVIEW DEBRIEF AND DOCUMENT REVIEW That night, Lisa and Joe looked through the documentation Ryan had given them. It contained current organizational charts and staff numbers. There were also spreadsheets showing the department cost allocations, broken out into rough groupings to provide an understanding of how the groups are weighted. See Figure 27.1 for the current organizational structure, Figure 27.2 for the cost allocations, and Figure 27.3 for the current headcount. The next day, Lisa and Joe set up time with the CFO, the CIO, and the CHRO, who were available on short notice, although they could only get a few minutes with each. As they headed over to the building, they discussed what they should ask to get the information they needed to create their approach, thinking through how they would structure the interviews and what information they required. Figure 27.2 Cost Allocation by Functional Area Figure 27.3 Current Shared Services Organization Headcount THE CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER'S PERSPECTIVE At the CFO's office, Lisa and Joe were greeted by his assistant, who asked them to have a seat, explaining that Gary was working on "putting out a fire." After a few minutes, Gary came out and escorted them into his office, apologizing for the delay. "There are still questions about the divestiture that we're all-hands-on-deck to answer. Seems like we just can't get it all done in the time we have. Plus, we're trying to get ready for the quarter close, and we have extra work this time around for the regulators, since we have to restate everything in terms of the new company financial structure. Like we need more work!" Lisa and Joe gave a brief overview of why they were there. They could be candid with Gary, who clearly knew the financial situation. "Yes," he said, "it's tough. Our shared services teams have been with us a long time-I came up through F\&A, been here 32 years. Ryan and I went to grad school together." Lisa got straight to the point and asked Gary to talk about his current structure within F\&A, as well as the impacts of the sale. Specifically, she asked about how F\&A interacted with other teams and what kinds of dependencies existed. He gave two main responses. "You know, for dependencies, one problem we always have is that our HR group doesn't understand what we do. We end up recruiting for ourselves, we just tell HR when we have someone we want to bring in. I don't even bother sending job requirements over to them anymore. We've actually brought in our own HR person to help us out, only we call her an administrative assistant. But she does all of our recruiting and on-boarding. Only thing she can't do is hire. But she does everything up to and after that. "Something I don't understand is why IT can't seem to do what we need. We always ask for things and they come back and say 'our project list is 2 years long, we can't help you today.' Seems to me we invested in this new system, but it can't do half of what we can do by ourselves. I'd rather have Kerry (one of his leads) run a spreadsheet for me than trust those guys over in IT to get something done. They always say we need to change because they can't help us with the system." Joe asked about team structures and how people move between teams-the kinds of growth and development opportunities available. Gary responded: "We can't afford to move people around for growth and development. The reward for figuring out how to do something is that you get to do it for the rest of your life. I still have to make the final adjustments for our quarterly board reports-it's too complicated for someone else to learn. As far as rewards, well, we incent people to find creative solutions to problems." As Lisa and Joe thanked him for his time, Gary reiterated, "I'm running a complex business here; we're not like anyone else. Whatever you come up with, it really needs to meet our unique processes and structure." THE CHIEF INFORMATION OFFICER'S PERSPECTIVE Lisa and Joe headed over to IT. Their documentation review had highlighted that the IT systems were mostly "old school," meaning COBOL programs running on mainframes. The new F\&A system that had been implemented was vendor supported, and there were very few internal resources in the IT group who knew how to work with it effectively. The CIO, Ken, was expecting them, and he seemed on edge during the conversation. He started off saying "You know I don't really understand why we even sold ELI. Seems like it was doing pretty well, and it was easy enough to support. What kind of strategy is it to sell off a money-making, easy-to-run business?" Ken continued on this vein for a few minutes. Lisa and Joe realized from their document review that the IT organization was one of groups that had much of its costs allocated to ELI, but which had not had a meaningful cost reduction associated with the sale. When asked, Ken admitted that they really didn't have a good idea of how much time anyone spent on any given system, and the work done for the divestiture was mostly "guesstimates." At that point, his pager went off, and he abruptly ended the meeting. THE CHIEF HUMAN RESOURCE OFFICER'S PERSPECTIVE The next stop was Human Resources. They wandered around the maze of cubes and offices, finally locating the CHRO, Henry. He was still wrapping up a meeting. "Come in," he called, as the person at the desk leaned forward and shouted, "But we need people on this-yesterday!" Lisa and Joe felt a little embarrassed and hovered at the door as the person finally gathered his paperwork and left the office in a huff. Henry just smiled and explained that GenLife executives were kicking off the assessment phase of an acquisition and resources were urgently needed to staff the team. "This happens at least a few times a year so we're pretty used to it," he said. "It's always a fire drill, but we get through it. Our folks are really dedicated and we reward them for the long days and weekends they put in." Lisa mentioned that the CFO seemed very busy. Henry laughed "They like to be heroes as much as we do!" As they sat, Henry filled Lisa and Joe in on the role of HR and its evolution over the past few years. "When Bill, the previous CHRO, left, it was a huge loss to GenLife," he said, "but culturally we needed to change to a more professional, dynamic organization, so it was probably for the best. Bill was pretty old-school when it came to HR." Henry admitted that he didn't have a strong HR background. He'd moved through the ranks of Finance and then later in Real Estate, but he had faith in the strength and size of his team, all 62 of them. "This year the team has been working on a new competency model, new executive training, succession planning, plus of course there's our future leaders program, skills training, our recognition program, wellness program, and the local community action program," he said, proudly showing a large wall chart of activities with hundreds of line items. "We're building a world-class HR department!" he exclaimed. "At GenLife we have over 200 people who have been with us for over 25 years-that says something about us." The biggest challenge Henry saw for the group was the existence of multiple systems being used to manage employee information, benefits, and compensation, with business units and acquired companies operating on different human resource information systems (HRIS). "We spend a lot of time transferring information and working on spreadsheets. Our HR generalists each support an area of the business and when we try to look across the business units, or even across Shared Services, we spend a lot of time reconfiguring and reformatting data just to get a picture of what's going on. Most of our employee files are actual physical files," he explained. "You can imagine with all our staff, we're thinking of renting an aircraft hanger!" Lisa smiled and asked, "Reporting must take up quite some time then?" Henry jumped up and went to grab some files, which he waved around as he responded. "Oh yes, we get new requests all the time from the business unit leads asking What's my loaded cost for each employee? Why am I spending so much on training? When can I get my open positions filled? But our generalists are amazing and very flexible, we pride ourselves on the range of things our HR generalists can pull out of their hats-heck we've even had generalists running SOX audits at a pinch!" As Lisa and Joe started to collect their notes, Henry confided, "To be honest, I'm not sure what this initiative is really going to achieve. We're already working overtime just to get through what needs to be done. I don't know how Ryan thinks we're going to be able to provide the same level of service with fewer people." Lisa and Joe returned to their office and sat down to categorize what they had learned. There were serious concerns about understanding the work being done in the organization and how the CEO's desires could be addressed through organizational design while also downsizing the staff. Process work would have to be done during the project, adding to the complexity. They had 3 days left to put together a pitch, and a lot of work ahead of them. Based on what they knew, they created an outline of a proposal. They decided to leverage the STAR model (Kates \& Galbraith, 2007) to evaluate what they know of the current situation and then plan out the rest of their week. Figure 27.4 STAR Model Application - Given your analysis of these dimensions, what are the key problems that need to be solved? - What type of approach would you take to the organizational design process? Discuss how you would approach documenting the current state and creating a future state. - What are the pros and cons of that approach? Whole Organizational Design Intervention - Using Galbraith's STAR model, evaluate what you know about the current situation in this organization. Complete each of the categories in Figure 27.4 at the end of the case. - Given your analysis through the STAR Model, what are the key problems/issues that need to be addressed? - Which organizational interventions(s) based on course material would you recommend addressing the key problems/issues? What are the pros and cons of each intervention that you recommend? G enLife, Inc. was an established multinational insurance company, was well-known in the area, and employed approximately 3,000 people, many locally. They had grown through an acquisition strategy over the past 10 to 15 years. They tended to acquire and absorb rather than leave businesses to run independently, but they often struggled to integrate systems and operations. In a recent effort to "get smaller to grow bigger," GenLife had sold off a part of its business that dealt specifically with executive life insurance (ELI) and approximately a third of its employees either joined the acquiring company, ExecuLife, or were let go, depending on their job functions. Most of these jobs were sales related, directly tied to the ELI business. Approximately a third of GenLife's revenue went to ExecuLife with the sale, and it was anticipated GenLife expenses would reduce by approximately a third as well. However, just 3 months after the sale, GenLife CEO Ryan Bind was finding that very little had changed in the cost structure of GenLife. Apparently ELI hadn't used corporate shared services very much, so there were still high support needs postsale. The remaining 256 PART II. CASES IN ORGANIZATION DEVELOPMENT INTERVENTIONS business of GenLife was left supporting the company, and it was simply too expensive to run. The estimates for how much cost would be eliminated at divestiture were off by as much as 30%. Many of the shared processes to support the remaining business were done through convoluted spreadsheets with arcane links that were understood only in parts by certain individuals and processes were largely undocumented. The company had invested significantly in a centralized system to assist in enterprise management processes, but very few people used it, preferring their manual processes. In summary, the sale of ELI had reduced revenue for GenLife with little reduction in overall costs. So the CEO called in consultants Lisa Mendez and Joe Henderson to address the situation. Drastic measures were required in the next 6 months to avoid serious financial damage. Six months was a hard date - at that point, GenLife would be running at a deficit if costs weren't reduced. The company's infrastructure was provided via a shared services structure for internal operations, including Human Resources (HR), Legal, Facilities, Finance and Accounting (F\&A), Real Estate (RE), Actuary, and Information Technology (IT). These seven groups had supported both the remaining and the sold businesses, and costs had been allocated evenly across all areas. With the divestiture out of ELI, a third of the revenue had been reduced, but the shared services organization had not shrunk in a similar way. In fact, of about 450 people, only 14 shared services resources had gone to ExecuLife. THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER'S PERSPECTIVE As the CEO, Ryan had approved the sale of the ELI business, and during the due diligence period had been convinced by his team that the business case was solid; however, that was proving to be incorrect. He knew now that the remaining business was too expensive to run without the ELI revenue. Ryan presented the financial situation to Lisa and Joe as both fact and history-as he put it, "There's nothing to be done about the mistakes that were made-we were wrong about how much of the shared infrastructure would move over, so now we need to reduce our costs. But we have to be able to run our business! So we can't just cut across the board and hope for the best. Plus, no one really knows how things get done around here. There is little documentation, mostly just people who have been doing their jobs for a long time. If we lose them, we'll go off the rails. So we need to do this thoughtfully and take advantage of the opportunity to put some things to right." Ryan explained his suspicion that the organization, which had grown haphazardly over the years, was not serving the real needs of the business. According to him, at an executive and senior level, some groups had been created just to give people something to manage as they got promoted, not necessarily because it made good sense. Some of the managers were better at lobbying for staff and funding and were providing "Cadillac" levels of service while others were bare-bones for no logical reason. The processes being used within the groups were, he felt, convoluted and based on legacy assumptions about what was necessary. There was no clear definition of what was minimally required versus what was "above and beyond" for running the business. Finally, he was convinced his executive team wasn't working well. "Look," he said, "I don't like this one bit. I've been with this company 35 years, and all these guys came up through the ranks with me. We just assume we are all doing our jobs well and don't check up on each other. But, things feel a little out of control if this is what it really costs to run our business. We're going to have to let people go, but I want to make sure we let the right people go, and we're going to have to change what we're doing, but I want to make sure we make the right changes. If it's going to be bad, let's get it all out there over the next 6 months and have an end date for the pain." Ryan also explained that if GenLife was going to be successful, the strategy of growth via acquisition would need to be supported by a lean and flexible shared service organization. "We need to be able to acquire and integrate new businesses without an equal increase in costs," He sighed. "But we can't seem to manage the business costs we have today." Ryan was concerned not only for the short-term future of GenLife, but its longterm viability in an increasingly cost competitive market. Ryan laid out a few guiding principles for Lisa and Joe. He wanted to: 1. Look everywhere for cost containment in addition to letting people go. 2. Take advantage of the situation to "get a handle" on processes. 3. Treat people fairly and be honest about the hard decisions that would have to be made-at a minimum, approximately 30% of the staff, or about 120 people, would have to be let go. There would be no option to reassign people from one group to another (a common avoidance technique among managers during a layoff). 4. Redesign the remaining groups to work better together-fast, efficient, and able to scale. He felt they were operating ineffectively as silos, and the management structure was "heavy" and did not support the strategy of getting small to grow big. 5. Be more thoughtful than the traditional management approach of simply telling each group to cut 30% of the staff and 30% of their expenses-data-supported recommendations were important. Ryan had some data that supported his perspective that the teams were not working well. He routinely found errors in accounting reports and had to proofread board slides and financial reports regularly to ensure accuracy. For a CEO of a mid- to large-sized corporation, this level of detailed review was a signal of a real problem further down in the organization. He also made the following points. - Most of the teams were led by people who had been in the company a very long time-the current CFO had been with the company for 35 years, for example. However, at entry levels in the organization, turnover was very high-higher than industry standards. Further, the middle management layer had expanded significantly over time. - The organization tended to reward firefighters. In exit interviews, younger employees in particular cited people "making their own fires so they could be heroes" as reasons why they left. Exiting employees also referred to the lack of career opportunity at GenLife. - Many people considered their work "nonnegotiable" due to their understanding of regulatory and reporting needs both internal and external to the organization, but Ryan wasn't convinced it was all necessary. - Only certain people in the organization understand the convoluted accounting structures, which are largely undocumented. At the end of the conversation, Lisa and Joe looked at each other. Joe spoke up first. "You've given us a good overview of what you want out of this and where you have concerns. But we're going to need some information from your people to really understand the breadth and depth of the issues and what it will take to solve them." The CEO wasn't thrilled. "Haven't you done this before?" "Sure," said Lisa, "and experience tells us there's more to this story than just your perspective. If you want us to give you a workable approach together with an accurate time and cost estimate for something that has a shot of working in the timeframe you've presented, we need more information." Ryan paused, and agreed to give them a week of access to his team, and any other information they deemed necessary. "But," he said emphatically, "I'm not paying you to tell me how much you are going to charge me! I know how consultants work. And don't forget, the clock is ticking-you are taking 1 week out of the 24 we have before time runs out." Lisa and Joe readily agreed to take on the investigation as a part of their business development effort, and got Ryan's commitment to send a note to his team to expect a call and to make time for an interview. INTERVIEW DEBRIEF AND DOCUMENT REVIEW That night, Lisa and Joe looked through the documentation Ryan had given them. It contained current organizational charts and staff numbers. There were also spreadsheets showing the department cost allocations, broken out into rough groupings to provide an understanding of how the groups are weighted. See Figure 27.1 for the current organizational structure, Figure 27.2 for the cost allocations, and Figure 27.3 for the current headcount. The next day, Lisa and Joe set up time with the CFO, the CIO, and the CHRO, who were available on short notice, although they could only get a few minutes with each. As they headed over to the building, they discussed what they should ask to get the information they needed to create their approach, thinking through how they would structure the interviews and what information they required. Figure 27.2 Cost Allocation by Functional Area Figure 27.3 Current Shared Services Organization Headcount THE CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER'S PERSPECTIVE At the CFO's office, Lisa and Joe were greeted by his assistant, who asked them to have a seat, explaining that Gary was working on "putting out a fire." After a few minutes, Gary came out and escorted them into his office, apologizing for the delay. "There are still questions about the divestiture that we're all-hands-on-deck to answer. Seems like we just can't get it all done in the time we have. Plus, we're trying to get ready for the quarter close, and we have extra work this time around for the regulators, since we have to restate everything in terms of the new company financial structure. Like we need more work!" Lisa and Joe gave a brief overview of why they were there. They could be candid with Gary, who clearly knew the financial situation. "Yes," he said, "it's tough. Our shared services teams have been with us a long time-I came up through F\&A, been here 32 years. Ryan and I went to grad school together." Lisa got straight to the point and asked Gary to talk about his current structure within F\&A, as well as the impacts of the sale. Specifically, she asked about how F\&A interacted with other teams and what kinds of dependencies existed. He gave two main responses. "You know, for dependencies, one problem we always have is that our HR group doesn't understand what we do. We end up recruiting for ourselves, we just tell HR when we have someone we want to bring in. I don't even bother sending job requirements over to them anymore. We've actually brought in our own HR person to help us out, only we call her an administrative assistant. But she does all of our recruiting and on-boarding. Only thing she can't do is hire. But she does everything up to and after that. "Something I don't understand is why IT can't seem to do what we need. We always ask for things and they come back and say 'our project list is 2 years long, we can't help you today.' Seems to me we invested in this new system, but it can't do half of what we can do by ourselves. I'd rather have Kerry (one of his leads) run a spreadsheet for me than trust those guys over in IT to get something done. They always say we need to change because they can't help us with the system." Joe asked about team structures and how people move between teams-the kinds of growth and development opportunities available. Gary responded: "We can't afford to move people around for growth and development. The reward for figuring out how to do something is that you get to do it for the rest of your life. I still have to make the final adjustments for our quarterly board reports-it's too complicated for someone else to learn. As far as rewards, well, we incent people to find creative solutions to problems." As Lisa and Joe thanked him for his time, Gary reiterated, "I'm running a complex business here; we're not like anyone else. Whatever you come up with, it really needs to meet our unique processes and structure." THE CHIEF INFORMATION OFFICER'S PERSPECTIVE Lisa and Joe headed over to IT. Their documentation review had highlighted that the IT systems were mostly "old school," meaning COBOL programs running on mainframes. The new F\&A system that had been implemented was vendor supported, and there were very few internal resources in the IT group who knew how to work with it effectively. The CIO, Ken, was expecting them, and he seemed on edge during the conversation. He started off saying "You know I don't really understand why we even sold ELI. Seems like it was doing pretty well, and it was easy enough to support. What kind of strategy is it to sell off a money-making, easy-to-run business?" Ken continued on this vein for a few minutes. Lisa and Joe realized from their document review that the IT organization was one of groups that had much of its costs allocated to ELI, but which had not had a meaningful cost reduction associated with the sale. When asked, Ken admitted that they really didn't have a good idea of how much time anyone spent on any given system, and the work done for the divestiture was mostly "guesstimates." At that point, his pager went off, and he abruptly ended the meeting. THE CHIEF HUMAN RESOURCE OFFICER'S PERSPECTIVE The next stop was Human Resources. They wandered around the maze of cubes and offices, finally locating the CHRO, Henry. He was still wrapping up a meeting. "Come in," he called, as the person at the desk leaned forward and shouted, "But we need people on this-yesterday!" Lisa and Joe felt a little embarrassed and hovered at the door as the person finally gathered his paperwork and left the office in a huff. Henry just smiled and explained that GenLife executives were kicking off the assessment phase of an acquisition and resources were urgently needed to staff the team. "This happens at least a few times a year so we're pretty used to it," he said. "It's always a fire drill, but we get through it. Our folks are really dedicated and we reward them for the long days and weekends they put in." Lisa mentioned that the CFO seemed very busy. Henry laughed "They like to be heroes as much as we do!" As they sat, Henry filled Lisa and Joe in on the role of HR and its evolution over the past few years. "When Bill, the previous CHRO, left, it was a huge loss to GenLife," he said, "but culturally we needed to change to a more professional, dynamic organization, so it was probably for the best. Bill was pretty old-school when it came to HR." Henry admitted that he didn't have a strong HR background. He'd moved through the ranks of Finance and then later in Real Estate, but he had faith in the strength and size of his team, all 62 of them. "This year the team has been working on a new competency model, new executive training, succession planning, plus of course there's our future leaders program, skills training, our recognition program, wellness program, and the local community action program," he said, proudly showing a large wall chart of activities with hundreds of line items. "We're building a world-class HR department!" he exclaimed. "At GenLife we have over 200 people who have been with us for over 25 years-that says something about us." The biggest challenge Henry saw for the group was the existence of multiple systems being used to manage employee information, benefits, and compensation, with business units and acquired companies operating on different human resource information systems (HRIS). "We spend a lot of time transferring information and working on spreadsheets. Our HR generalists each support an area of the business and when we try to look across the business units, or even across Shared Services, we spend a lot of time reconfiguring and reformatting data just to get a picture of what's going on. Most of our employee files are actual physical files," he explained. "You can imagine with all our staff, we're thinking of renting an aircraft hanger!" Lisa smiled and asked, "Reporting must take up quite some time then?" Henry jumped up and went to grab some files, which he waved around as he responded. "Oh yes, we get new requests all the time from the business unit leads asking What's my loaded cost for each employee? Why am I spending so much on training? When can I get my open positions filled? But our generalists are amazing and very flexible, we pride ourselves on the range of things our HR generalists can pull out of their hats-heck we've even had generalists running SOX audits at a pinch!" As Lisa and Joe started to collect their notes, Henry confided, "To be honest, I'm not sure what this initiative is really going to achieve. We're already working overtime just to get through what needs to be done. I don't know how Ryan thinks we're going to be able to provide the same level of service with fewer people." Lisa and Joe returned to their office and sat down to categorize what they had learned. There were serious concerns about understanding the work being done in the organization and how the CEO's desires could be addressed through organizational design while also downsizing the staff. Process work would have to be done during the project, adding to the complexity. They had 3 days left to put together a pitch, and a lot of work ahead of them. Based on what they knew, they created an outline of a proposal. They decided to leverage the STAR model (Kates \& Galbraith, 2007) to evaluate what they know of the current situation and then plan out the rest of their week. Figure 27.4 STAR Model Application - Given your analysis of these dimensions, what are the key problems that need to be solved? - What type of approach would you take to the organizational design process? Discuss how you would approach documenting the current state and creating a future state. - What are the pros and cons of that approach

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts