As Emily Levy began to settle into her seat on a crowded train from Penn Station to

Question:

As Emily Levy began to settle into her seat on a crowded train from Penn Station to Boston, a four‐plus‐hour commute that was now becoming a frequent event, she began to think of how far the company she had founded two years earlier had come.

Graduating from college just months earlier in May 2016, Emily now found herself with a substantial investment offer that would allow her to grow her company, but she knew the next 12 months would be challenging. Emily had successfully developed and brought to market a product focused on improving the health‐care experience for patients. She now wondered whether her company could rely on one product or whether she could disrupt a broader market within wellness wear.2 Emily knew the decision she was about to make would have significant implications for the future success and sustainability of her company.

Early Years

To say that Emily Levy was born into a family of fashion industry entrepreneurs would be an understatement. While Emily was growing up, Emily’s mother established a successful career in fashion, having helped open and run a Giorgio Armani store in the heart of Boston, Massachusetts, before transitioning into advertising roles at Hill Holiday, a leading advertising firm. While her mother focused on high‐end fashion, Emily’s father targeted more casual customers with his retail clothing store selling apparel to surfing, skateboarding, and snowboarding enthusiasts. Emily’s brother, 12 years her senior, followed in the family’s footsteps.

After graduating from college, he launched his own sales representative company, “GL Sales,” selling on behalf of O’Neill and other apparel companies. All three ventures provided Emily with direct insight and exposure to product design, manufacturing, wholesale and retail sales. Starting in the eighth grade, Emily balanced time at her father’s store with her schoolwork, while also working with her brother to organize product samples for him on the weekends. Unfortunately, the recession of 2000 significantly affected her father’s store, leading to bankruptcy. Emily recalled “seeing first‐hand what being an entrepreneur was and how unforeseen macro risks can impact a company.”3 In high school, Emily participated in three sports, including serving as captain for both field hockey and lacrosse, and completed a number of AP classes, including psychology. Emily had always been interested in humanities and the human element of history. While school never came easy to her, she took pride in her work ethic and never backed down from challenges. After graduating from high school, Emily considered a number of undergraduate business programs before accepting a four‐year scholarship to Babson College as a Center for Women’s Entrepreneurial Leadership (CWEL) scholar. The mission of CWEL is to “create a gender‐enlightened business ecosystem where a diverse range of entrepreneurial leaders is encouraged to create economic and social value for themselves, their organizations, and society.”4 The Center provides female students with an opportunity to further develop and build confidence in their leadership skill. Knowing that she wanted to start her own business eventually, Emily believed Babson’s focus on women entrepreneurs would help her accomplish her dream. It was at Babson that Emily began to surround herself with a number of mentors who worked at the Center, often reaching out to them for feedback and advice.

Following her freshman year of college, Emily’s focus on social entrepreneurship continued to grow as she took part in a three‐week program that sent female students to Rwanda to teach entrepreneurship. In 2010, Babson had partnered with the Rwanda Private Sector Federation to establish the Babson Rwanda Entrepreneurship Center (BREC) with the mission of strengthening Rwanda’s entrepreneurial environment:

BREC will partner with Babson’s Center for Women’s Leadership Program to send a team of 5–8 of Babson’s Women’s Leaders from across campus to Save, Rwanda for three weeks in the Summer of 2013 for the second year in a row to teach entrepreneurship, leadership and academic skills to 9th and 10th grade Rwandan students, conduct a women’s leadership seminar at the National University of Rwanda, work alongside aspiring and successful female entrepreneurs of Rwanda, and engage with women empowerment organizations all while getting the opportunity to explore the nation’s capital of Kigali and other unique Rwandan experiences.5 Reflecting on her time in Rwanda, Emily recalled her participation in this program and the unique timing of this trip, “I loved to see how resilient the people in Rwanda were. They taught me that just because you have a bad situation, it doesn’t mean you can’t have a positive life. I definitely have taken that into my own business and personal philosophy.”6 Between her sophomore and junior years in college, Emily traveled to Israel for a three‐month internship. When she arrived in Israel, it was a time of peace, but that soon changed as Hamas began firing rockets toward Israel, eventually leading to the 2014 Israel–Gaza conflict. Emily recalled:

It was a life changing experience. I was there when there was conflict and remember how I just kept working, even though I had friends who kept going into Gaza after being called into the military. One weekend we were surfing with some friends and the next weekend one of them was injured in the conflict and lost his hearing. Just seeing how they kept on working in the face of adversity made me realize that I could embody this attitude too. It’s something I’ll never forget.7

Diagnosing an Opportunity

In seventh grade, Emily had been bitten by a tick, but there was no physical evidence of the bite; doctors had failed to notice symptoms of common diseases associated with tick bites.

Throughout high school, Emily had constantly found herself tired and clumsy, often complaining of body pains. In an effort to diagnose and treat her ailments, Emily had met with physical therapists, psychological therapists, holistic doctors, and even had attempted acupuncture, to no avail. For seven years, Emily had struggled physically and mentally to cope each day with fatigue and pain. Prior to leaving for Rwanda in 2013, Emily had completed additional tests; once she returned home, she learned that she had tested positive for Lyme disease.

Lyme disease is prevalent in the United States. “The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that 300,000 people are diagnosed with Lyme disease in the US every year.

That’s 1.5 times the number of women diagnosed with breast cancer, and six times the number of people diagnosed with HIV/AIDS each year in the United States. However, because diagnosing Lyme can be difficult, many people who actually have Lyme may be misdiagnosed with other conditions. Many experts believe the true number of cases is much higher.”8 Treatment for Lyme disease can vary but in severe cases can require intravenous medication delivered directly to a patient’s heart via a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC line).

Doctor insert a PICC line, a sterile, flexible catheter, into a vein in the patient’s arm and thread it up to the heart, where it can remain in place for days, months, or years depending on the treatment. While PICC lines prevent patients from undergoing IV injections for each treatment, they leave the patient with an exposed end of the catheter outside of the body. Doctors commonly use PICC lines to deliver nutrients and medication for chemotherapy; PICC lines also allow easy access for drawing blood.

In December of her sophomore year, Emily received her first PICC line, which was scheduled to last for six months. Following the placement of the line, nurses and doctors told Emily to wear a cut‐off sock over her arm if she wanted to cover the entry port, which she tried when returning to campus. During her freshman year, Emily had been involved in numerous clubs on campus and had actively participated in social scenes. With a cut‐off sock added to her fashion wardrobe, everything began to change. Fellow students and friends began inquiring about the sock‐covered PICC line and would often stare at her when she had to administer her treatment in public areas. Emily rapidly saw her extroverted personality become much more introverted.

As Emily worked to complete her sophomore year, she began to question whether a cut‐off sock was the best option to cover her PICC line.

Creating a Solution

In the spring of 2014, Emily and fellow Babson student, Yousef Al‐Humaidhi, started to explore options to cover her PICC line.

They purchased a number of products that were intended to cover PICC lines, but quickly concluded that they failed to meet Emily’s needs. In many cases, Emily even preferred the cut‐off sock to some of the products they evaluated. This initial product research pushed Emily and Yousef to design their own solution.

In the fall of 2014, they created their first prototype, which Emily personally used and tested, prior to Babson’s annual Rocket Pitch event.9 Following the three‐minute pitch of their business concept, Emily received strong positive feedback from a number of attendees who told her that the market needed her prototype and business idea and urged her to continue to move forward. Emily left that day with renewed motivation to bring her PICC line cover to market.

In the spring of 2015, Emily took the prototype with her to attend classes at Babson’s San Francisco campus. Throughout the semester, she continued developing the company by using her product for class projects. Through this experience, fellow Babson student Maria del Mar Gomez Viyella joined Emily and Yousef to further build the venture. Emily was fortunate to have Professor Jim Poss, founder and CEO of Big Belly Solar and WeModifi, as her mentor while on the West Coast, absorbing valuable guidance, insights, and encouragement to “just go” and take action.

While in San Francisco, and subsequently when she returned to Boston after the semester, Emily began to focus on raising seed capital to fund her first manufacturing purchase order of \($10,000,\) which ultimately rose to \($16,000.\) Until now, Emily and Yousef had funded the company with an initial investment of \($11,000.\) The majority of this capital had already been invested in designs and prototype development, so Emily needed to look elsewhere.

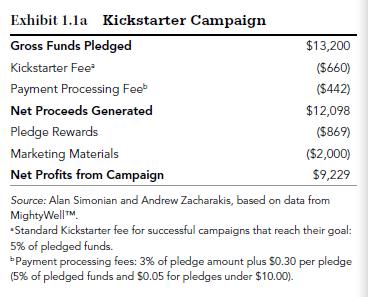

• Kickstarter—Emily established a 30‐day online Kickstarter campaign with the goal of raising \($10,000.\) The campaign was completed under the company’s former name PICCPerfect.

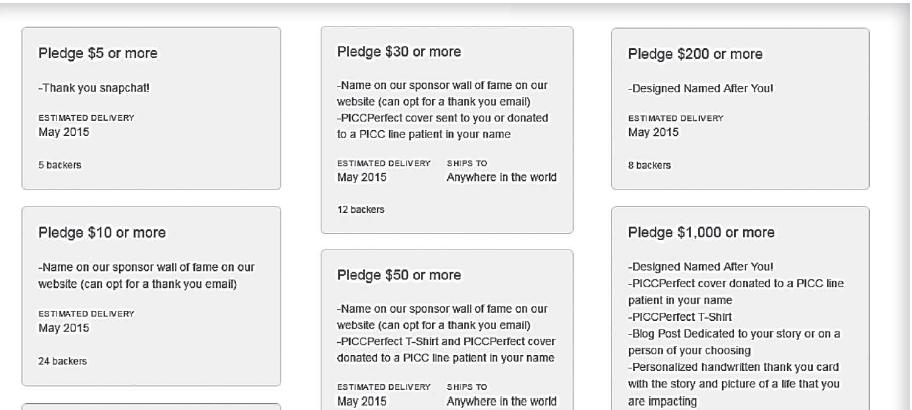

She chose Kickstarter over other crowdfunding platforms for three primary reasons: Kickstarter was a known and recognizable global platform, their campaign fees were comparable to other global fundraising sites, and the site had proven successful for entrepreneurs developing physical consumer products. Prior to launching, she received advice from previous entrepreneurs who attempted to raise their own funding; they recommended that she spend time and resources to create a comprehensive marketing plan for the campaign. This advice was reinforced in conversations with many individuals she spoke with who had failed to complete a Kickstarter campaign successfully and subsequently had faced roadblocks from future investors who quickly took notice of their failed funding attempts. In light of this, Emily invested \($2,000\) to develop professional marketing materials and videos, with the intent of leveraging these for future marketing purposes. Following Kickstarter’s 30‐day period, Emily’s campaign was oversubscribed and raised \($13,200,\) with both domestic and international donors pledging funds. The final campaign generated net proceeds of \($12,188\) for her company, with 70% of funds generated from friends and family and the remaining 30% from individuals who wanted to purchase the product for themselves or someone else. After creating and shipping all pledge rewards for donors and deducting the cost of marketing materials, Emily’s profits from the campaign were \($9,249\) (see Exhibit 1.1 for details).

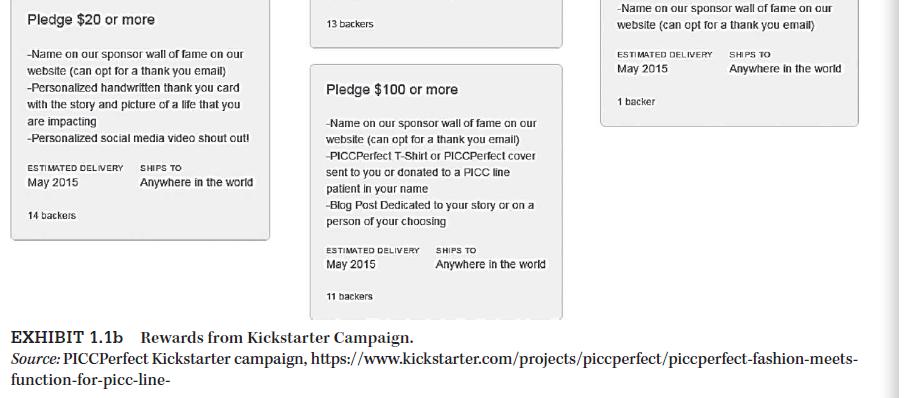

• Business competitions—In addition to funding the company through Kickstarter, Emily entered several business competitions in the Greater Boston area. Between 2015 and 2016, Emily participated in 17 business competitions and won first prize in 15. These competitions provided the company with \($225,000\) in funding and in‐kind professional services and did not dilute Emily’s ownership or that of her cofounders (see Exhibit 1.2 for details). While Emily invested significant resources and time away from her business to attend these competitions, she gained increased publicity and guidance from industry peers, successful entrepreneurs, and investors.

Soon thereafter, Emily’s market research uncovered that 2.5–3 million patients in the United States receive PICC lines each year.10 This information, along with feedback she had received from patients, nurses, mentors, and the Kickstarter campaign, led her to realize, “This isn’t just Emily who has this problem, it’s an addressable market of 3 million potential customers.”

Emily returned to Boston for the summer before her senior year at Babson to participate in Babson’s Summer Venture Program (SVP). Graduate and undergraduate students accepted into this program receive housing, work spaces, and access to advisors over the course of an intensive 10‐week period designed to foster meaningful advances for their ventures.

Since launching in 2009, this program has assisted over 150 students in the development of 109 ventures, including companies such as Virool and ThinkLite in 2010 and HigherMe in 2014.12 Subsequent to SVP, HigherMe was accepted into Y Combinator, which invests small amounts into new ventures and runs the companies through an accelerator program, and Virool successfully raised over \($27M\) in two rounds of funding led by venture capital fi rm, 500 Startups.

SVP provided an environment for the participants to not only learn from the mentors (successful entrepreneurs, investors, and professors) but also from other teams in SVP. Like Professor Poss in San Francisco, mentors in SVP pushed Emily to attend industry conferences to market her company and product.

One of the fi rst industry meetings she attended was targeted to vascular access nurses. This conference opened Emily’s eyes even further as she began to question whether a broader market existed outside of PICC line covers. She continued to hear from existing customers of PICC lines who urged Emily to consider developing products and solutions for other medical conditions and treatments. The question Emily now faced was whether she could pivot and transform her young company from a singleproduct venture into a larger company focused on wellness wear for patients.

PICC Line Cover Product Overview

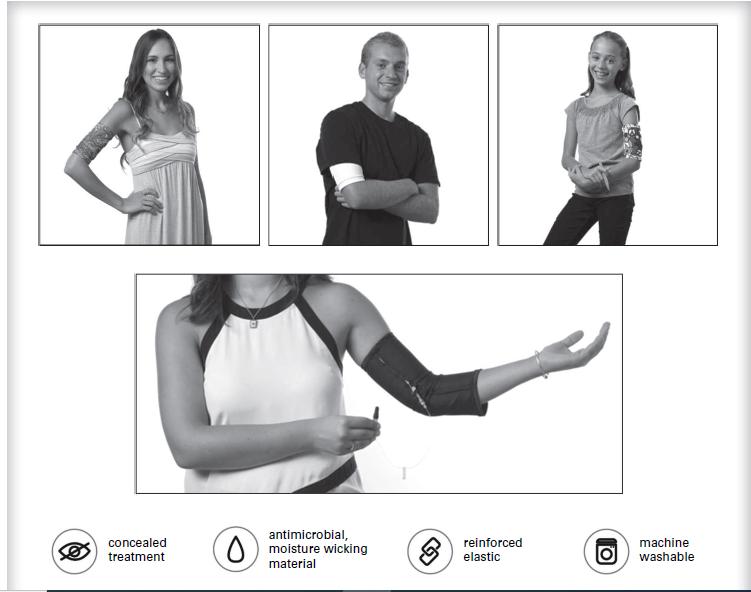

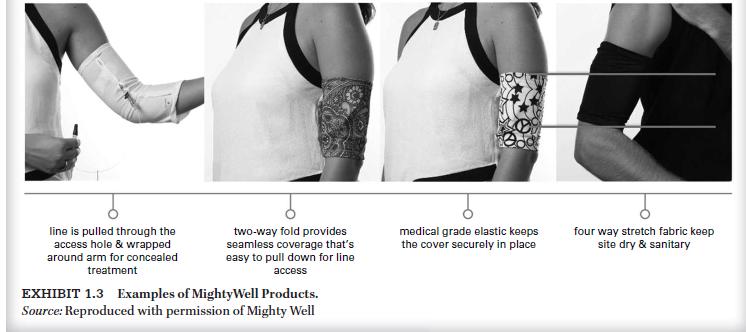

PICCPerfect™ was designed to provide a functional and fashionable solution to PICC line covers. The product was manufactured using four‐way stretch, antimicrobial, nontoxic, moisture wicking fabric to keep the site dry and sanitary. Each machine‐washable cover was designed to stay in place at all times using medical‐grade elastics. The product’s double‐way fold feature made treatment easier by fully concealing the PICC

line and creating a barrier between the tubing and a patient’s skin (see Exhibit 1.3 for examples of the PICCPerfect™ product).

Target market of MightyWell™ was women in the United States between the ages of 18 and 36, a market segment Emily identified based on a combination of industry data and historic purchasing demographics from the company’s initial sales. To date, the company had relied on word‐ofmouth advertisement, business competitions, and free press from their Kickstarter campaign as means to sell their first 1,000 units during Emily’s senior year. The majority of these initial sales were direct to consumer through the company’s website and e‐commerce platforms such as Amazon, priced at \($29.95.

Following\) her first production order, Emily evaluated the effectiveness of their current manufacturer, based in California.

She uncovered numerous units in their first order that had been incorrectly manufactured and failed to meet quality standards.

In 2016, Emily decided to change manufacturers and selected a firm based in Providence, Rhode Island, for their next order of 2,500 units. This change reduced production costs by 40%, which increased gross margins from 47% to 68%. While further cost reductions may have been possible by moving manufacturing overseas, Emily had committed to keep manufacturing in the United States for all products that touch patient wound sites. The challenge that MightyWell™ faced with their new manufacturer was their company’s size and purchasing power relative to the size of other companies their new manufacturer worked with. The small order size of MightyWell™ limited the company’s negotiating power with its supplier. However, Emily knew the increase in product quality and expansion of gross margin that MightyWell™ gained significantly outweighed longer manufacturing times and delays.

Industry Overview

The majority of new ventures in the fashion and wellness industries can be segmented into two categories, those that clearly fall within one of the above industries and those that span multiple industries. MightyWell™ was in the second category, with influences from multiple industries and sectors including health care, wholesale manufacturers, and retail, as the company sold directly to consumers.

Health Care and PICC Lines

Since the 1970s, doctors and nurses had commonly used PICC lines to deliver antibiotics directly to the heart. With an estimated U.S. annual volume of 2.5 million and 5 million on an international scale, PICC line usage is growing rapidly.13 While the rate of bloodstream infections associated with PICC line patients was less than those experienced via similar procedures, doctors and nurses recommended that patients keep the wound site clean. Numerous studies had shown patients who receive PICC lines in an outpatient setting and subsequently returned home had a lower rate of infection compared to those who remained in hospital settings.14 Given these statistics, a segment of PICC line patients admitted to hospitals for extended periods of time may have presented MightyWell™ with an opportunity to target this customer base.

Wholesale Manufacturers

The North American Industry Classification System (NAISC)

identified “Women’s, Children’s, and Infants’ Clothing and Accessories Merchant Wholesalers” as a sector within the Wholesale Trade industry classification. In Q2 of 2016, this sector created 249 startups within the United States with average annual sales exceeding \($3.9M.\) Most new ventures within the “small business” category employed four employees, with average annual sales per employee exceeding \($996,000.\) In aggregate, these 249 startups generated annual revenues of approximately \($988M,\) representing 4.6% of the sector’s \($21B\) total revenue.15 Between 2013 and 2015, the number of wholesale companies in this sector, both small and large businesses, remained flat, with less than a 1% overall change. However, the industry’s average two‐year cessation rate, that is, firms who failed to stay in businesses, was 12.3%. This rate had remained constant over recent years, with the most recent data from 2015 showing 164 startups still in operation compared to the same 186 that had been started in 2013.16 The U.S. textile, apparel, and luxury good market had maintained average gross margins between 46% and 49% over the last five years, but had increased margins 650 basis points since 2006. Industry experts expected future margin improvement based on advances in technology and falling commodity prices. Many believed that “companies with strong brands, differentiated products, and attractive price‐value propositions are likely to outperform their peers.”17 Furthermore, the industry’s historical average earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT)

margin over the last 10 years was 12.75%. The industry EBIT margin was highly impacted by the 2009 U.S. recession, as industry averages fell below 11% before rebounding to a peak of 14.25% in 2014.18

Retail

According to a 2016 Mintel Market report, the U.S. clothing industry generated revenue of \($239.9\) billion in 2015, representing a 4.1% year over year growth rate. This sector was forecasted to experience a 2.9% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) through 2020, reaching \($284.3\) billion, with increases in spending per capita of the U.S. population and increases in the consumer price index driving many of the advances.19 The U.S. clothing market has three main segments: women, men, and children. The following values reflected sales and growth between 2008 and 2015:

• Women comprised 53.3% of industry sales, growing at 1.71% CAGR.

• Men comprised 27.4% of industry sales, growing at 2.49% CAGR.

• Children comprised 19.3% of industry sales, growing at 1.51% CAGR.20 A high volume of suppliers, brands, and retailers fragmented the women’s clothing market. The Mintel report identified an opportunity for companies to focus on women between the ages of 18 and 34, as this market segment was the most engaged and involved in shopping for fashion. Furthermore, the report suggested, “the notion of self‐gifting is a ripe opportunity for marketers that can tap into both rational and emotional mindsets.

Nearly one in three bought clothing as a treat or reward, and this can be amplified through direct marketing communication.”

The highest concentration of women purchasing clothing as a self‐gift was within the age range of 35–44, as 42% of respondents stated they purchase clothing as a treat or reward.21 The U.S. women’s retail sector continued to see a shift in purchasing trends, moving from in‐store purchases at traditional brick‐and‐mortar locations to online e‐commerce purchases.

In 2015, 24% of women purchased clothing directly through Amazon, with 66% of women having purchased at least one article of clothing online. This trend had risen 300 basis points, up from 63% in 2013.22

Successes to Date

During the summer of 2016, MassChallenge accepted Emily’s venture as one of 128 ventures, out of over 1,700 applicants; Mass- Challenge was a global startup accelerator for early stage entrepreneurs that did not receive an equity position from companies in exchange for their participation in the program. While in this program, Emily began to rebrand her company and implement a marketing strategy to transform the company from a singleproduct identity with the PICCPerfect cover to a comprehensive consumer brand for patients, caregivers, and health professionals.

The transformation not only included branding, changing her company name from PICCPerfect to MightyWell™, but also a number of new products scheduled to launch in 2017–2018 that included PortPerfect™, for patients undergoing chemotherapy, and PillPerfect™, a new version of a pill box.

Months later, in September, MightyWell™ entered the Babson Breakaway Challenge, a business competition sponsored by CWEL at Babson College and Breakaway, a Boston‐based brand capital firm. This competition promoted gender parity and awards \($250,000\) in convertible debt to women entrepreneurs and ventures with consumer‐facing businesses. Mighty-

Well™ was one of 23 semifinalists, then one of five finalists, and subsequently became the 2016 winner of the Babson Breakaway Challenge. In addition to the funding, Emily received in‐kind business services that included TV and digital advertising campaigns, print media campaigns, legal services, and use of shared workspaces. Upon receiving the \($250,000\) in convertible debt funding, she also gained access to a team of experienced branding experts who continued to mentor and help her navigate MightyWell™’s transformation and growth.

Moving Forward

Emily was proud of her achievements and the journey she had started years earlier. While she saw the benefits of expanding and diversifying via new product lines, she questioned what types of products made sense. Emily worried that expanding too quickly might lead her to neglect her current emerging product and existing customer base. Could she manage all these elements at once? Could she successfully grow MightyWell™ in the next 12 months while ensuring the long‐term sustainability for her company?

Discussion Questions

1. What are the advantages and disadvantages of adding new product lines?

2. If she goes forward, how would you advise Emily to identify these lines?

3. What criteria should she use in deciding what products to add?

4. How can Emily balance expanding her existing base of PICCPerfect customers while educating new markets of customers with other medical needs?

5. Does a hybrid market opportunity exist for MightyWell™’s wellness wear?

6. What are the positives and negatives for the way in which Emily has bootstrapped her company up to this point?

Step by Step Answer: