Question: Five years after buying his first sewing machine, Scott Hunter was telling friends about the conversation with Yvon Chouinard, the legendary rock climber and environmental

Five years after buying his first sewing machine, Scott Hunter was telling friends about the conversation with Yvon Chouinard, the legendary rock climber and environmental advocate who founded the global apparel and equipment brand Patagonia.

Years before—while a student in the MBA program at Babson College—he had sought to interview Chouinard for a paper he had to write, but was unable to connect. After graduation, Hunter began work on designs for backpacks to be sold under his newly launched brand, Vedavoo. He worked with outside designers, and struggled to identify an offshore factory to manufacture his bags. One of these in China looked promising, but ultimately rejected his project after Nike bought all unused capacity. In another case, he shipped a prototype bag that had cost him thousands to another potential partner in Vietnam, only to have the design stolen and the intermediaries he was expecting to do business with disappear. After months of effort, Hunter found himself down to his last \($700\) with little to show for the time and capital invested to that point.

By fate or divine guidance, Hunter received a very unexpected call.

Mr. Chouinard’s assistant called me and said, “Yvon’s got 20 minutes this afternoon. If you’ve got time, he would be happy to speak with you.” So I jumped on it, and the conversation lasted about an hour. We swapped stories about hiking and climbing in Wyoming before he asked, “Okay, tell me about your business.” I told him what I was working on, and the challenges I’d faced. He said, “If you can’t build something with your own hands, you have no business being in business.

You’ve got to learn what’s involved in making it, how it goes together and why things are the way they are so that you can figure out ways to build it better, easier, and more cost effective.

How can you expect others to make something for you if you don’t even know what your designs will force them to do? Go buy a sewing machine and learn to sew!”

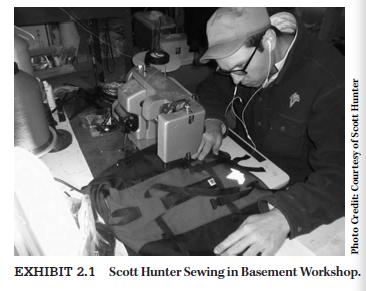

Inspired by Chouinard’s advice, Hunter went straight to Craigslist and used \($300\) of his remaining funds to purchase a used sail‐making machine. He drove from his home west of Boston down to Providence, Rhode Island, to pick it up. He returned home, and following the time‐honored, classic American entrepreneur tradition, set up the machine in his garage. Filled with determination, he used another \($300\) to purchase enough materials to make a few backpacks, paid his website up for the year to come, and began teaching himself to sew with a \($12\) safety net. He explained his plans for the company, which he named VEDAVOO, after an area in the Medicine Bow Routt National Forest in Wyoming. 2 “I decided it’s going to be made in America, and we’re going to use American‐sourced goods. We’re going to build on‐demand. We’re going to follow this path whether it’s custom goods or our core products” (see Exhibit 2.1 ).

Company Background

Scott Hunter grew up in Wyoming, spent much time outdoors hunting and fishing, and graduated from the University of Wyoming in 2005. During his senior year, he was a finalist in a business plan competition with his concept for Changing Leaf Designs, 3 a start‐up that would make large modular backpacks for backpacking.

Though he did not win the competition, the effort established an entrepreneurial passion in his heart to be pursued in time.

Upon graduation, Hunter took a job in Wyoming as an Internet salesman, ultimately moving up within the company to a Project and Account Management position developing wireless telecommunications systems for the oil business. Finding little personal value in this work, Hunter left the business and returned to his initial plan to make backpacks. He applied to Babson College, hoping to enroll and learn skills he would need as an entrepreneur launching a start‐up. To his surprise, he gained acceptance to the one‐year program and promptly moved to Massachusetts.

In 2009, Hunter launched his backpack company while finishing his program at Babson. His plan was still to make large, modular trekking packs. After facing many challenges, including bad advice from respected experts and losing money in deals with unscrupulous offshore agents, Hunter reframed his business plan to focus on building smaller, simpler designs that would be designed internally for domestic production. By 2014, Hunter had established and begun to grow a successful enterprise fabricating fly fishing packs from his home base in Lancaster, Massachusetts. He noted, “We just try to keep evolving and let the market dictate.”

Sales revenue had not yet reached one million, but product orders were growing and the company had high expectations.

Hunter summed it up. “Coming back to my passions and to the things I love has been incredible. Knowing we’re creating new jobs and new opportunities in the state is unbelievably fulfilling for me.”

The Entrepreneurial Process

Generating the Idea: Outdoor Life Shapes the Entrepreneurial Vision

During his early years in Wyoming, Scott Hunter hiked, fished, and camped in the mountains and rivers of his home state.

He was active in Boy Scouts of America and in their service branch, the Order of the Arrow,4 building trails and portages and other conservation projects. He was elected state president, then five‐state regional president, then the National Vice‐Chief in 2001. He taught leadership skill development and advocated conservation minded outdoor programs from this platform.

Heading off to the University of Wyoming, Hunter planned to study aeronautical engineering. He commented, “Frankly, after one semester, I realized it was completely wrong for me.

I’m a people person. I couldn’t sit behind a desk with a calculator all day and just crunch numbers. I needed to get out and talk to folks and be me.” He enrolled in the College of Business and studied Business Administration.

In his senior year, Hunter pursued and was granted special clearance to substitute the traditional capstone thesis with a business plan to be entered in the Wyoming \($10K\) entrepreneurship competition during the academic year 2004–2005. Previously during a summer internship in Washington, D.C., he had worked for Senator Mike Enzi from Wyoming. While in Washington, Hunter frequently heard people talk about the decline of American manufacturing and outsourcing. His concern grew, and he resolved not to outsource.

I knew I needed to write a business plan, so I tried to pick something I had a lot of passion for, something I loved. I decided that starting a bag and pack business with everything made in the USA could be the way to go. At the time, a lot of things were going overseas. I saw manufacturing jobs leaving, and you couldn’t buy a Made in the USA backpack anymore. That really bothered me! I was selected a finalist with the first iteration of what would become Vedavoo. I got to pitch to local angel investors, but was graciously told I was far from ready. So I went back to finish my undergraduate study and to look for a real job to gain some experience before I took it forward again.

Transition from Desk Job to Entrepreneur

Hunter turned down a marketing job in D.C. and took a job near Lander, Wyoming, as an Internet salesman. “It wasn’t the most glamorous opportunity, but I wanted to be close to the outdoors, to stay close to what I loved.” He moved up the ranks quickly and was transferred to a sister company in wireless telecommunications system consulting and design for oil fields. As director of business development, he met with clients and worked on big‐ticket contracts, but knew he was not fulfilled. “It was a big jump in a short time, and it was very good work. But at the end of the day, I was killing myself for very little personal value.”

He decided to chase his dreams as an entrepreneur. His plan was to reframe his early plan to build large trekking packs that could be converted to other uses such as a tent or a sleeping bag. “My concern as a backpacker was that I would hike in with this huge pack that weighed a lot, but once I got to camp it had no useful purpose.”

Hunter arrived at Babson College, bringing with him his concept for the backpack company, now named Pingora Pack Company.

Outsourcing vs. Personal Values

Hunter used his time to prepare his company for launch while at Babson. Soon, he was forced to change the name of the venture again after learning that another pack company had rights to the name “Pingora.” He drew inspiration for a new name from another of his favorite areas in his home state of Wyoming, the area known as Vedauwoo in the Medicine Bow Routt National Forest. Hunter opted for an easier to pronounce and spell variation of the park’s name, choosing “VEDAVOO” for the brand under which he would focus on building modular backpacking equipment. Prospective financiers for his venture and advisers alike strongly encouraged him to go overseas for manufacturing.

Through a contact at Babson, Hunter identified a design studio in California with the capability to convert his ideas into prototypes, and to further coordinate material selection, sourcing, and fabrication in China. Hunter explained, “They were a one‐stop‐shop.

They could help me select materials for my bag. They could do all the coordination and sourcing themselves, and then take it to a factory in China. I wasn’t thrilled to give up on keeping production domestic, but at that point it seemed more important to win the battle first, then come back to the US with production later when we had the brand and the resources to support the move.”

Although it meant sacrificing his personal values at least temporarily, Hunter decided to proceed with the California design firm. “So I went to the designer with a patent pending technology for a modular backpack, and spent hours trying to make it real.

Everything was looking up for the brand, and people were getting excited about our first products, but the pack proved too complicated for him to build a sample or to attract interest from capable factories overseas. There were too many things that had to work together just right. There was a huge fear the pieces wouldn’t operate the right way and that we would have a high waste ratio because of the number of pieces that had to fit together perfectly.

So factories pushed us away, the designer was pushing us away, and we went back to the drawing board. Looking back—this was a blessing in disguise. Even if it had been produced, it would have retailed around \($700\) in a niche that really only accounted for about 5% of the global pack market at that point.”

Reframing the Strategy

Looking for simple alternatives to bring to market after the abandonment of the modular trekking pack, Hunter worked with the designer on three other options. The first was a bear bag he had developed with a team of fellow students in Babson’s Product Design & Development class. This bag was designed to be suspended from a tree, thus holding food and other “smellable”

cooking and camping items at a height above the reach of bears.

The second was a shoulder sling with removable storage pouch based on a concept he had envisioned while fl y fishing. The third was a new hiking backpack design with modular padding that gave users the ability to customize their pack to better fit their bodies and comfort preferences. He pursued a provisional patent on this, and worked again with the California designer to generate final designs and prototypes for each of the products.

The California designer also worked in parallel for other notable brands such as Marmot, CamelBak, REI, and Eastern Mountain Sports and was therefore unable to complete work quickly for Hunter. Turnaround for prototypes of the designs took several months to receive and cost thousands of dollars. The single backpack prototype (see Exhibit 2.2 ) alone cost Hunter \($5800.\) Though each of the new options was much simpler in design, the California designer still struggled to locate suitable manufacturing overseas. Potential factories viewed the projects as too complex and the company too small to offer adequate return.

After several months without progress, Hunter and the design firm found the challenges too great and ended their relationship.

If I wanted to be a success, I had to reduce my dependence on outside sources, and be able to do more myself. I needed to have the ability to work directly with potential factories so that I could work through potential hang‐ups.

I needed to be able to do my own sourcing. I went back to the Outdoor Retailer show on a mission to find myself a factory.

Another New Beginning

In January of 2010, now approaching a year into the business without serious revenue, without sellable packs, without a factory, and without a designer, Hunter attended the Outdoor Retailer Winter Market Show in Salt Lake City. Carrying the prototypes of the modular padding backpack and bear bag, he spoke with several potential partners before coming to an agreement with a group from South Korea that managed a pack factory in Vietnam. This factory was known for work they did for Mont‐Bell, another notable, premium brand. Through a translator, they agreed Hunter would send the only existing sample of his modular padding backpack, and using this, they would develop a line of three sizes of backpacks built to use the same customizable padding technology that was in the prototype. Hunter shipped the pack and never heard from the company again. He related the saga.

I tried to fight it for a little while, but it became clear that the South Korean company was just an intermediary. They had sold themselves as the owner of the factory when in reality they were just a contractor using the factory’s resources.

At some level, the design got stolen. So picture this: I had put in a year, spent an exorbitant amount of money, and had nothing to show for it! I didn’t even have the backpack anymore to be able to try and figure out how to rebuild it!”

In March of 2010, having spent so much of his capital in the efforts to that point, Hunter reached a point when he had only \($700\) left in the company account. After the struggles to that point, he was faced with giving up on his dream, or finding a way to keep it alive. He remembered his early conversations with others who had followed similar paths like Wayne Gregory (the founder of Gregory Packs), and drew heavily on his conversation with Yvon Chouinard. Each in their own way had encouraged him to follow a similar path. “Learn to sew!” He also returned to his early goal of producing all of his products in the United States. Taking the advice and his values to heart, he bought a used industrial sewing machine off Craigslist for \($300,\) bought \($300\) worth of materials, and paid his website up for another year. With a \($12\) safety net and limited revenue from the sale of Vedavoo tshirts, Hunter went to his garage and taught himself how to sew.

Using old daypacks and duffel bags from Goodwill and garage sales, Hunter studied how packs and bags were made. He cut them apart, made patterns out of brown paper grocery bags, and tried to recreate them using his own fabrics. He learned to understand how curves worked to create depth. He learned how square cutouts could be used to make corners. He learned the importance of sewing consistently straight lines, and just how difficult it was to make them.

Though Hunter struggled with reproducing existing products, he had to be able to do much more than copy other products for Vedavoo to succeed. He wanted to learn how to design products himself so that he could use the machine to turn his ideas into realities without outside help. Joining several pieces of two‐dimensional fabric into a single three‐dimensional shape was a significant challenge that outweighed the sewing itself.

When weeks of practice gave him a reasonable grasp on this, he then taught himself how to refine those shapes so that they would each fit together perfectly. He reflects.

Those days were so hard. I had no money. I had no experience building gear. All I had was my dream, my passion, and a commitment to keep the company alive. Having never sewn before, my early products were as could be expected—but they laid a foundation that I use still today.

His greatest challenge at this stage, however, was finding a niche with genuine opportunity for an American Made bag company to succeed and developing products that would deliver real value for customers there. He reflects.

After we struggled to find traction in backpacking, I wasn’t sure where to turn next. I knew I still wanted to keep the venture in the outdoor industry, but it was tough to narrow down to a niche I could work in. Vedauwoo—the inspiration for the company’s name—is known for many types of outdoor adventure, but more than anything, it’s known for rock climbing. So I was getting all kinds of interest from rock climbers through social media. I decided to follow the energy there and to focus my efforts on building rope bags, duffels, chalk bags, and simple backpacks for climbers to carry their gear in. I knew little about the sport, but they gave me great ideas and the energy they brought in support of our new brand convinced me.

Through this process, Hunter learned the ins and outs of how to build gear: how to pattern, how to build, how to prototype, how to put things together. “I learned how to do all that, and instead of paying \($5,800\) for a single pack, now I had my own patterns, the ability to make my own prototypes, and for the first time, I had products that were truly my own designs.”

Serendipity Strikes

Armed with a line of packs and bags for rock climbers, Hunter raised new capital and went a second time to the Outdoor Retailer Trade Show in the summer of 2011. This time he had his own booth. However, a few problems became apparent.

They put me on the back wall in a corner from hell because I was a first‐timer. There was no light above the booth. I got my stuff set up, and the few people who actually made it back that far started saying, “If I can buy a similar pack made in China for \($40,\) why would I pay \($80\) for yours?”

American Made wasn’t enough to justify the difference for a sport where the bulk of the money is spent on things that keep climbers from falling. To put it mildly, I was feeling like a complete failure. As I neared the end of the show, I had no sales, no serious interest, and was ready to give up and move on. But late on the last day, a gentleman came by the booth with a wheelchair. He had his video camera mounted to it so it worked like a rolling tripod. Though he was definitely soliciting me to pay him for other videos later, he offered to do the first video for free, and I said, “Sure.” At that point, I had nothing left to lose. Much to my surprise, he scanned the packs on display and kept walking. He pointed at the back of the booth, where a sling pack I had built for myself to use fly fishing after the show was hanging. He said, “I want to do the video on that!” I didn’t even have it named until he asked me what it was called while filming.

Another Surprise Phone Call

A week after the show, Hunter received a phone call from a person who ran the International Fly Tackle Dealer (IFTD)

Show.5 He told Hunter, “We have the show next week in New Orleans, and I want you to be there. I saw this video online, and I’m really impressed. I think you’d be perfect for this market.

We need new guys and new blood in the industry, and I think you’d be fantastic!” Hunter had spent nearly all his money on his Outdoor Retailer booth and said he could not afford to attend. The Fly Tackle Show manager offered Hunter a booth for free. (“Just don’t tell anybody.”)

Hunter grabbed one of his climbing designs, altered it slightly to work as a fly fishing daypack, developed a simple lanyard, grabbed his personal sling pack, and went to New Orleans. He thought, “We’ll see what happens.” To his immense surprise, the gear was a hit. “People loved what we were doing.

They loved the ideas and the new brand. Our designs were different.

Plus, we found that fly fishermen had a lot more money to spend than climbers did!”

Hunter learned this market, unlike rock climbing, was not composed of college kids with no money. Instead it was 35‐ to 40‐year olds and up with discretionary income to spend. Hunter thought back to his conversation with Yvon Chouinard and how he had mentioned among other plans that he considered building packs for fly fishing. Chouinard had told him not to touch it, that fly fishing was a “dying market.” The show clearly proved otherwise. In fact, Hunter saw that fly fishing was changing.

It was no longer solely for 35+ year old men. A new market segment was emerging that was younger, passionate, and interested in having gear that was different and designed better and more durably than the gear their fathers and grandfathers used.

Stores and media professionals quickly took note, and Hunter got his first legitimate orders.

Hunter identified a factory in Pennsylvania and placed preliminary orders with them to build the fly fishing products that had enjoyed success at the trade show: the sling pack, the chest pack, and the day pack. Two days before the order was scheduled to ship, Hunter telephoned the factory to confirm billing details and learned they had not yet begun production. Hunter exclaimed, “So here I am again, I’ve had my first real glimmer of success, then the factory I was counting on so desperately completely dropped the ball! I fired my factory, called all of my first customers, told them what was happening, and told them my plans to bring everything back in‐house.” Hunter reflects.

It was so tough in 2012 because every pack shipped I had built myself. But it was truly a blessing in disguise. I was a one‐man show, so I built only what actually sold because I didn’t have time to build up an inventory. It took me probably five times what it should have, but I made sure that I built it right so that it would last. And at least I was building it myself! I didn’t have that cost, and I wasn’t depending on an outside source. I was able to build on demand and keep moving forward. This established the baseline for the business model we have now, giving us the opportunity to build on demand with only minimal inventory. We get paid up front for sales, build to order, and stay nimble and cash efficient with everything we do!

Strategy Decisions

In early 2016, as Hunter looks back on the five years since he bought his sewing machine, he reviewed how Vedavoo had progressed and recognized two things: he was building packs, which had been his initial dream; and he was sourcing everything he could in the United States, in line with his personal values. There had been many challenges along the way, well more than many would deem worth fighting through, but also a few lucky breaks that no one could have planned.

Key strategy decisions had sometimes evolved organically without deliberate planning. They had allowed the business to stay true to its original focus, and also to scrape through when the going got tough.

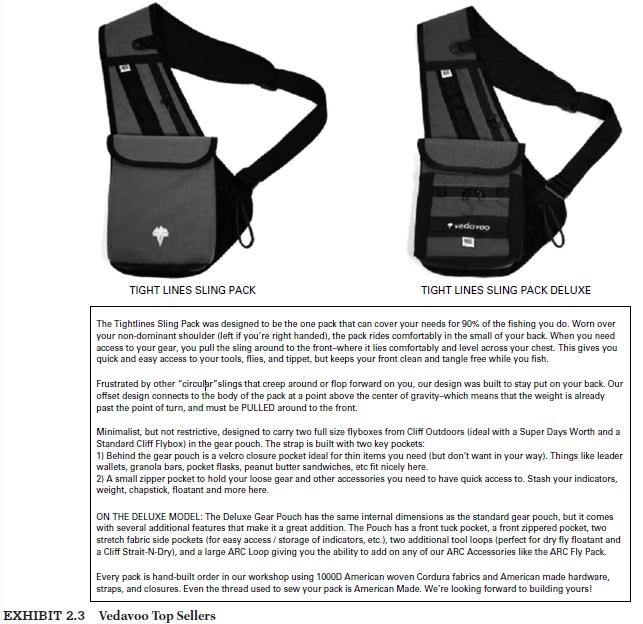

1. Product focus: Abandoned backpacking and rock climbing in favor of a central focus on fly fishing. Relaunched in 2012 with two products that sold immediately: a chest pack and a sling pack. Followed with a Daypack, and several simple storage solutions that also saw quick success. Continues to keep line simple, but innovates regularly to keep the line fresh while developing new solutions for greater market share (see Exhibit 2.3 ).

2. Pricing: Looked at other packs on the market and set Vedavoo prices only slightly higher, typically around 10 dollars more, to suggest greater value but not so far removed from competitors that higher numbers seemed unreasonable. “The pricing worked, and we’ve been able to increase our price more on some things. People continued to buy, and sales actually went up when we increased the price. It’s a shame that I underpriced a bit upfront, but without knowing clearly what my costs were, I just did my best. As we’ve grown, we’ve learned new tricks that help us be more effi cient with our most expensive input—labor hours—and we’ve found ways to make new products easy to build and standing products easier to build so we can be more profi table.”

3. Quality control: Built everything “to perfection” to assure no returns and to protect brand reputation.

4. Customization: Decided early on to offer customization.

Customers asking for specifi c features gave Hunter new ideas for product improvement and development. “We were able to make continuous iterations, compared to a company with a lot of inventory made overseas that they are stuck with for a year.”

5. American sourcing: “If I was going to hang the fl ag, it had to represent the entire picture.” Initially all packs were built in Massachusetts. Later, Hunter added other work‐fromhome sewers from around New England and as far South as Maryland. Further, he used American‐made inputs wherever possible. Heavy duty, 1,000 denier military grade Cordura nylon that was “more than double the thickness and density of the best pack cloth on the market” improved durability, and 500 denier cordura was used for linings. Buckles, zippers, Velcro, webbing, and even the sewing thread used to make the products came from U.S. manufacturers. Nonfabric products were also U.S.‐made, for example, bottles from the Pacifi c Northwest, and apparel produced in Southern California.

Future Growth

Hunter discussed how Vedavoo was positioned to grow. “We have grown no less than 83% per year since 2012—at least doubling in every other year. More business comes with added costs and greater need for a strong team. Could we grow faster if we went out and got a big angel? Probably. Do we want to grow faster? Not really. Organic growth has been excellent, and is letting our team develop and grow in a positive way together as we take on more work.”

My expectation was to come to Babson for the one‐year program, graduate, and move back. I expected to launch the business out west, use Wyoming‐based manufacturing, and work with folks I already had contact with from the local business council. But, we made the decision to stay in Massachusetts and have built a community around ourselves.

It was defi nitely not the ideal location for a new outdoor brand, but it’s been perfect for American craft manufacturing, and I’ve found other people here that have helped make the dream a reality.

New England has this strong manufacturing mindset, and people and facilities here were part of that culture.

It has been a good place to develop our business. Things may have gone downhill when all the factories closed, but the people who sewed here remain. We’ve been fortunate enough to gain staff from factories long since outsourced, and they already know the craft when they sit down to sew their fi rst sling. We have stay‐at‐home moms and grandmothers, single ladies, and college kids. It’s been awesome.

The best example is a stay at home mother of three that lives in the same town I do, and we met at a local festival. Her husband came through and said, “Hey, I want that pack!” and she followed with “I can sew that.” So I asked her on the spot if she wanted an interview. She’s become my right‐hand in the business and works as our production team manager now.

Cash remained a challenge, and Vedavoo was covering bills with incoming revenue. Capacity to build for large orders had begun to loom as a growth concern.

Every day we are challenged by new orders and less time to build them. As strong as our team is, it wasn’t built overnight. Finding skilled and talented professionals is difficult and takes time. Our greatest risk is growing too fast, but we’ve been slowly planning for the storm since 2014.

Hunter began a program to develop and grow as the business grows. His “workshop team” handles day‐to‐day manufacturing on an at will basis. Historically, this team did it all. With significant growth and the increase in partner and retail orders, it became clear that a quick spike in ordering could quickly overwhelm this team. He linked with a manufacturing facility in western Massachusetts late in 2014, and has continued to work with the factory on large‐scale projects since that time.

The factory had run successfully for many years but was forced to close when the outsourcing movement began. Hunter appreciated New England’s rich manufacturing history that extended from the 19th through the 20th century.

Vedavoo now focused on fly fishing products. Seasonality and geographic region were important to this market. Hunter noted that certain times of year were busier than others.

Our biggest season starts at Thanksgiving and goes through Easter. That’s by far our heart and soul. Christmas buying season is followed immediately by consumer show season.

In 2014, we did ten of these events, and they were a huge success. That year we surpassed 2013 net before we got to the end of the first quarter. Our slow down happens thereafter through mid‐summer. We have used this time to build for cobranded projects, new orders for retailers, and some inventory for the holiday to come. Every minute sewing is a minute making money—and we try to keep everyone running smooth and even all year, buffering the seasonality.

By the time we hit fall, people start ramping up again leading into Thanksgiving.

Customer interest in Vedavoo had begun in New England and the Northern Rocky Mountains where freshwater fishing was practiced, then strong sales developed in the Southeast.

Hunter said about 75% to 80% of customers were male, parallel to industry participation. “People going out for saltwater fishing have also picked up our stuff. They’ve been very happy with it, so a lot of new potential, and recently expansion into international markets as well.” Discussing competition, Hunter named standby industry leaders like Orvis6 and Fishpond7 he tries to focus on his work so that he always competes with himself. Hunter often invited potential customers at trade shows to try on a competitor’s pack, then come back and try on a Vedavoo pack. At the beginning, Hunter thought Made in the USA would be the primary driver of sales, but he learned gear functionality was the real key to winning a customer.

In our case, the weight stays put on your back better because of the way our pack is shaped. You can lean over and the pack still stays put, whereas with the others, the pack flips to the front and gets in your way, or slides down your back. We also designed the pack to keep your front clean and free, with the pack riding flush on your back until you need it.

On the future of the industry, Hunter believed Vedavoo held a good place.

Fly Fishing was probably considered “a dying industry”

because the active angler was getting older, and products homogenized. When we entered the industry, you could look at two sling packs from different companies, they look very similar, all built by Asian factories.

They were feature rich but over so. These companies lost sight of the critical piece, which was how it felt, carried, and functioned once the user was there. Conditions were ripe for new entrants—and this coupled with a huge emergence of fly fishing as a “cool” active sport in the 18–35 demographic. Seeking “different”

than their fathers and grandfathers, and driving demand for Made in America product. We started as that wave started and we’ve been fortunate as a result. Getting more younger people and kids into the sport is the center pin of our longevity.

Discussion Questions

1. Does Scott have the right characteristics to be an entrepreneur? Discuss his entrepreneurial process. Is it effective?

2. Is Vedavoo an opportunity? Why or why not?

3. Evaluate Vedavoo using the Timmons Framework. How would you move forward if you were Scott?

EXHIBIT 2.1 Scott Hunter Sewing in Basement Workshop. Photo Credit: Courtesy of Scott Hunter

Step by Step Solution

3.37 Rating (147 Votes )

There are 3 Steps involved in it

The text provided presents the case of Scott Hunter and his journey in creating and developing his backpack company Vedavoo This story is a typical entrepreneurial journey with its unique set of chall... View full answer

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts