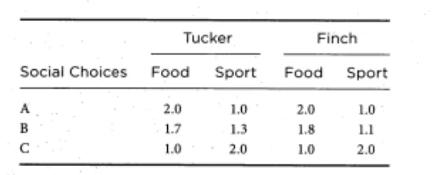

Society consists of two individuals, Tucker and Finch; there are two goods, food and water sport (recreation);

Question:

Society consists of two individuals, Tucker and Finch; there are two goods, food and water sport (recreation); and there are three social choices, A, B, and C, involving different amounts of the two goods for Tucker and Finch: \({ }^{34}\)

Tucker's preferences are a bit different than Finch's. Let \((2.0,1.0)\) represent an bundle of food (first argument) and sport (second argument). Tucker likes the following bundles, in order from best to worst: \((2.1,1.0) \bullet(1.0,2.0) \bullet(2.4,0.7) \bullet(1.7,1.3) \bullet(2.0\), 1.0). Furthermore, all bundles containing less than 0.9 units of sport are inferior to \((1.0,2.0)\). For Finch, the bundles, from best to worst, are \((1.4,1.4) \bullet(1.0,2.0) \bullet(1.6\), 1.3) (1.8, 1.1) \(\bullet(2.0,1.0)\). For Finch, all bundles with less than 1.2 units of sport are inferior to \((1.0,2.0)\).

a. In a graph with food on the horizontal axis and sport on the vertical axis, draw an indifference curve for Finch and one for Tucker, through the point (1.0, 2.0). Apply the specific bundles for which we know rankings. Do individual preferences appear to be problematic?

b. Between social choices A and B, which does our two-person society prefer? Why?

c. Is there a way to shuffle around the total amount of food and sport in choice A (between Tucker and Finch) so that your answer to (b) is reversed?

d. Why does this result suggest the compensation principle is flawed? That is, to be meaningful, winners actually have to compensate losers for the social choice judgment to be valid.

Step by Step Answer: