Question: Precision Systems, Inc. (PSI)* Precision Systems, Inc. (PSI) has been in business for more than 40 years and has generally reported a positive net income.

Precision Systems, Inc. (PSI)*

Precision Systems, Inc. (PSI) has been in business for more than 40 years and has generally reported a positive net income. The company manufactures and sells high-technology instruments (systems). Each product line at PSI has only a handful of standard products, but configuration changes and add-ons can be accommodated as long as they are not radically different from the standard systems.

Faced with rising competition and increasing customer demands for quality, PSI adopted a total quality improvement program in 1989. Many employees received training and several quality initiatives were launched. Like most businesses, PSI concentrated on improvements in the manufacturing function and achieved significant improvements. However, little was done in other departments.

In early 1992, PSI decided to extend its total quality improvement program to its order entry department, which handles the critical functions of preparing quotes for potential customers and processing orders. Order processing is the first process in the chain of operations after the order is received from a customer. High-quality output from the order entry department improves quality later in the process, and allows PSI to deliver higher quality systems both faster and cheaper, thus meeting the goals of timely delivery and lower cost.

As a first step, PSI commissioned a cost of quality (COQ) study in its order entry department. The study had two objectives:

• To develop a system for identifying order entry errors

• To determine how much an order entry error costs.

PSI’s Order Entry Department

PSI’s domestic order entry department is responsible for preparing quotations for potential customers and taking actual sales orders. PSI’s sales representatives forward requests for quotations to the order entry department, though actual orders for systems are received directly from customers. Orders for parts are also received directly from customers. Service-related orders (for parts or repairs), however, are generally placed by service representatives. When PSI undertook the COQ study, the order entry department consisted of nine employees and two supervisors who reported to the order entry manager. Three of the nine employees dealt exclusively with taking parts orders, while the other six were responsible for system orders. Before August 1992, the other six were split equally into two groups: One was responsible for preparing quotations, and the other was responsible for taking orders.

The final outputs of the order entry department are the quote and the order acknowledgment or “green sheet.” The manufacturing department and the stockroom use the green sheet for further processing of the order.

The order entry department’s major suppliers are (1) sales or service representatives; (2) the final customers who provide them with the basic information to process further; and (3) technical information and marketing departments, which provide configuration guides, price masters, and similar documents (some in printed form and others online) as supplementary information. Sometimes the printed configuration guides contain information in the format the order entry requires, but other times it does not.

At times there are discrepancies in the information available to order entry staff and sales representatives with respect to price, part number, or configuration. These discrepancies often cause communication gaps between the order entry staff, sales representatives, and manufacturing.

An order entry staff provided the following example of lack of communication between a sales representative and manufacturing with respect to one order.

If the sales reps. have spoken to the customer and determined that our standard configuration is not what they require, they may leave a part off the order. [In one such instance] I got a call from manufacturing saying when this system is configured like this, it must have this part added. . . . It is basically a no charge part and so I added it (change order #1) and called the sales rep. and said to him, “Manufacturing told me to add it.” The sales rep. called back and said, “No [the customer] doesn’t need that part, they are going to be using another option . . . so they don’t need this.” Then I did another change order (#2) to take it off because the sales rep. said they don’t need it. Then manufacturing called me back and said, “We really need [to add that part (change order #3). If the sales rep. does not want it then we will have to do an engineering special and it is going to be another 45 days lead time. . . .” So, the sales rep. and manufacturing not having direct communication required me to do three change orders on that order; two of them were probably unnecessary.

A typical sequence of events might begin with a sales representative meeting with a customer to discuss the type of system desired. PSI’s sales representatives have scientific knowledge that enables them to configure a specific system to meet a customer’s needs. After deciding on a configuration, the sales representative then fills out a paper form and faxes it or phones it in to an order entry employee, who might make several subsequent phone calls to the sales representative, the potential customer, or the manufacturing department to prepare the quote properly. These phone calls deal with such questions as exchangeability of parts, part numbers, current prices for parts, or allowable sales discounts. Order entry staff then keys in the configuration of the desired system, including part numbers, and informs the sales representative of the quoted price. Each quote is assigned a quotation number. To smooth production, manufacturing often produces systems with standard configurations in anticipation of obtaining orders from recent quotes for systems. The systems usually involve adding on special features to the standard configuration. Production in advance of orders sometimes results in duplication in manufacturing, however, because customers often fail to put their quotation numbers on their orders. When order entry receives an order, the information on the order is re-entered into the computer to produce an order acknowledgment. When the order acknowledgment is sent to the invoicing department, the information is reviewed again to generate an invoice to send to the customer.

Many departments in PSI use information directly from the order entry department (these are the internal customers of order entry). The users include manufacturing, service (repair), stockroom, invoicing, and sales administration. The sales administration department prepares commission payments for each system sold and tracks sales performance. The shipping, customer support (technical support), and collections departments (also internal customers) indirectly use order entry information. After a system is shipped, related paperwork is sent to customer support to maintain a service-installed database in anticipation of technical support questions that may arise. Customer support is also responsible for installations of systems. A good order acknowledgment (i.e., one with no errors of any kind) can greatly reduce errors downstream within the process and prevent later non–value-added costs.

Cost of Quality

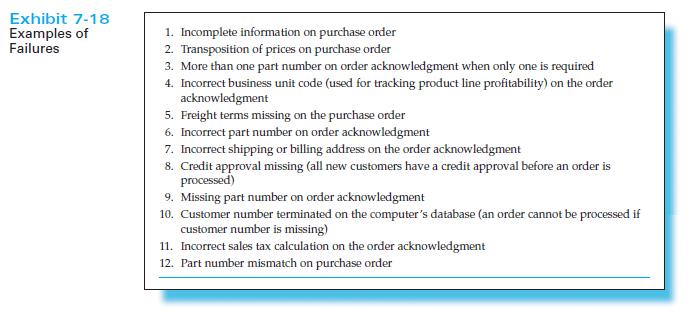

Quality costs arise because poor quality may—or does—exist. For PSI’s order entry department, poor quality or nonconforming “products” refer to poor information for further processing of an order or quotation (see Exhibit 7-18 for examples). Costs of poor quality here pertain to the time spent by the order entry staff and concerned employees in other departments (providers of information, such as sales or technical information) to rectify the errors.

Class I Failures

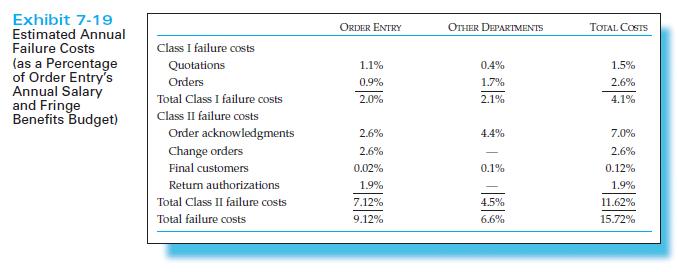

Class I failure costs are incurred when nonconforming products (incorrect quotes or orders) are identified as nonconforming before they leave the order entry department. The incorrect quotes or orders may be identified by order entry staff or supervisors during inspection of the document. An important cause of Class I failures is lack of communication. Sample data collected from the order entry staff show that they encountered more than 10 different types of problems during order processing (see Exhibit 7-18 for examples). Analysis of the sample data suggests that, on average, it takes 2.3 hours (including waiting time) to rectify errors on quotes and 2.7 working days for corrections on orders. In determining costs, the COQ study accounted only for the time it actually takes to solve the problem (i.e., excluding waiting time). Waiting time was excluded because employees use this time to perform other activities or work on other orders. The total Class I failure costs, which include only salary and fringe benefits for the time it takes to correct errors, amount to more than 4% of order entry’s annual budget for salaries and fringe benefits (see Exhibit 7-19).

Class II Failures

Class II failure costs are incurred when nonconforming materials are transferred out of the order entry department. For PSI’s order entry department, “nonconforming” refers to an incorrect order acknowledgment as specified by its users within PSI. The impact of order entry errors on final (external) customers is low because order acknowledgments are inspected in several departments, so most errors are corrected before the invoice (which contains some information available on the

order acknowledgment) is sent to the final customer. Corrections of the order entry errors do not guarantee that the customer receives a good quality system, but order entry’s initial errors do not then affect the final customer. Mistakes that affect the final customer can be made by individuals in other departments (e.g., manufacturing or shipping).

Sample data collected from PSI’s users of order entry department information show that more than 20 types of errors can be found on the order acknowledgment (see Exhibit 7-18 for examples). The cost of correcting these errors (salary and fringe benefits of order entry person and a concerned person from another PSI department) accounts for approximately 7% of order entry’s annual budget for salaries and fringe benefits (see Exhibit 7-19).

In addition to the time spent on correcting the errors, the order entry staff must prepare a change order for several of the Class II errors. A change order may be required for several other reasons that cannot necessarily be controlled by order entry. Examples include (1) changes in ship-to or bill-to address by customers or sales representatives, (2) canceled orders, and (3) changes in invoicing instructions. Regardless of the reason for a change order, the order entry department incurs some cost. The sample data suggest that for every 100 new orders, order entry prepares 71 change orders; this activity accounts for 2.6% of order entry’s annual budget for salaries and fringe benefits (see Exhibit 7-19).

Although order entry’s errors do not significantly affect final customers, customers who find errors on their invoices often use the errors as an excuse to delay payments. Correcting these errors involves the joint efforts of the order entry, collections, and invoicing departments; these costs account for about 0.12% of order entry’s annual budget (see Exhibit 7-19).

The order entry staff also spends considerable time handling return authorizations when final customers send their shipments back to PSI. Interestingly, more than 17% of the goods returned are because of defective shipments, and more than 49% fall into the following two categories: (1) ordered in error and (2) 30-day return rights. An in-depth analysis of the latter categories suggests that a majority of these returns can be traced to sales or service errors. The order entry department incurs costs to process these return authorizations, which account for more than 1.9% of the annual budget (see Exhibit 7-19). The total Class I and Class II failure costs account for 15.72% of the order entry department’s annual budget for salaries and fringe benefits. Although PSI users of order entry information were aware that problems in their departments were sometimes caused by errors in order entry, they provided little feedback to order entry about the existence or impact of the errors.

Changes in PSI’s Order Entry Department

In October 1992, preliminary results of the study were presented to three key persons who had initiated the study: the order entry manager, the vice president of manufacturing, and the vice president of service and quality. In March 1993, the final results were presented to PSI’s executive council, the top decision-making body. During this presentation, the CEO expressed alarm not only at the variety of quality problems reported, but also at the cost of correcting them. As a consequence, between October 1992 and March 1993, PSI began working toward obtaining the International Organization for Standardization’s ISO 9002 registration for order entry and manufacturing practices, which it received in June 1993. The effort to obtain the ISO 9002 registration suggests that PSI gave considerable importance to order entry and invested significant effort toward improving the order entry process. Nevertheless, as stated by the order entry manager, the changes would not have been so vigorously pursued if cost information had not been presented. COQ information functioned as a catalyst to accelerate the improvement effort. In actually making changes to the process, however, information pertaining to the different types of errors was more useful than the cost information.

Required

(a) Describe the role that assigning costs to order entry errors played in quality improvement efforts at Precision Systems, Inc.

(b) Prepare a diagram illustrating the flow of activities between the order entry department and its suppliers, internal customers (those within PSI), and external customers (those external to PSI).

(c) Classify the failure items in Exhibit 7-18 as internal failures (identified as defective before delivery to internal or external customers, that is, Class I failures) or external failures (nonconforming “products” delivered to internal or external customers, that is, Class II failures) with respect to the order entry department. For each external failure item, identify which of order entry’s internal customers (that is, other departments within PSI who use information from the order acknowledgment) will be affected.

(d) For the order entry process, how would you identify internal failures and external failures, as defined in question (c)? Who would be involved in documenting these failures and their associated costs? Which individuals or departments should be involved in making improvements to the order entry process?

(e) What costs, in addition to salary and fringe benefits, would you include in computing the cost of correcting errors?

(f) Provide examples of incremental (fairly low-cost and easy to implement) and breakthrough (high-cost and relatively difficult or time consuming to implement) improvements that could be made in the order entry process. In particular, identify prevention activities that can be undertaken to reduce the number of errors. Describe how you would prioritize your suggestions for improvement.

(g) Discuss the issues that PSI should consider if it wishes to implement a web-based ordering system that permits customers to select configurations for systems.

(h) What nonfinancial quality indicators might be useful for the order entry department? How frequently should data be collected or information be reported? Can you make statements about the usefulness of cost-of-quality information in comparison to nonfinancial indicators of quality?

*Source: Institute of Management Accountants, Cases from Management Accounting Practice, Volume 12. Adapted with permission.

Step by Step Solution

3.48 Rating (164 Votes )

There are 3 Steps involved in it

a Assigning costs to order entry errors played a critical role in quality improvement efforts at Precision Systems Inc PSI by quantifying the financial impact of those errors The cost of quality COQ s... View full answer

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts