Question: 1) (VRIN) analysis: Using your analysis above, briefly state what you believe to be the companys 1-2 major capabilities or core competencies (if any) and

1) (VRIN) analysis: Using your analysis above, briefly state what you believe to be the companys 1-2 major capabilities or core competencies (if any) and assess their ability to create a sustainable competitive advantage by explaining EACH of the four VRIN criteria for EACH competency. Be sure to state the results of your VRIN analysis (i.e. competitive disadvantage, competitive parity, temporary competitive advantage, or sustainable competitive advantage).

2) CURRENT STRATEGY analysis: In light of your analysis above, what are the companys current strategy types (i.e. type of business level, corporate level, cooperative and international strategies the company is pursuing)? What is your evidence from your analysis for this assessment?

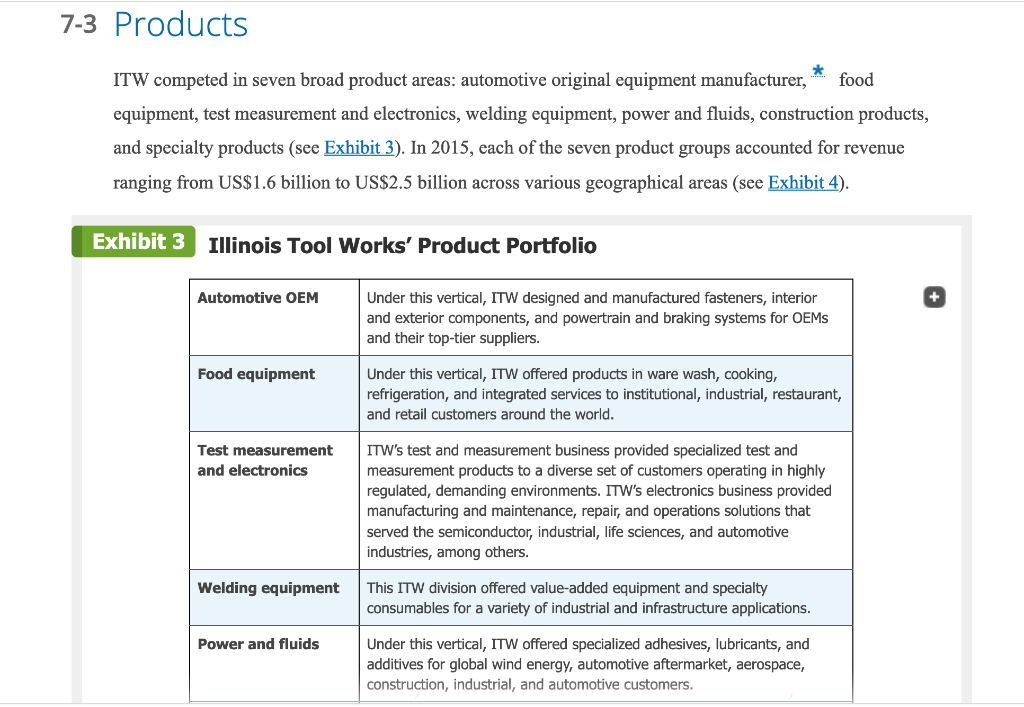

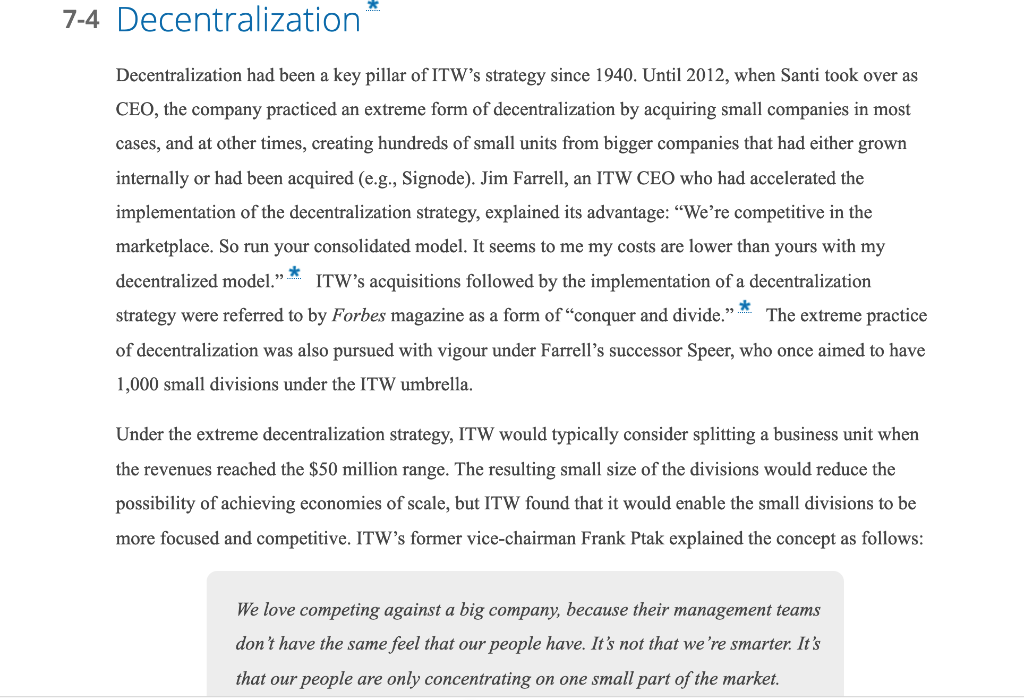

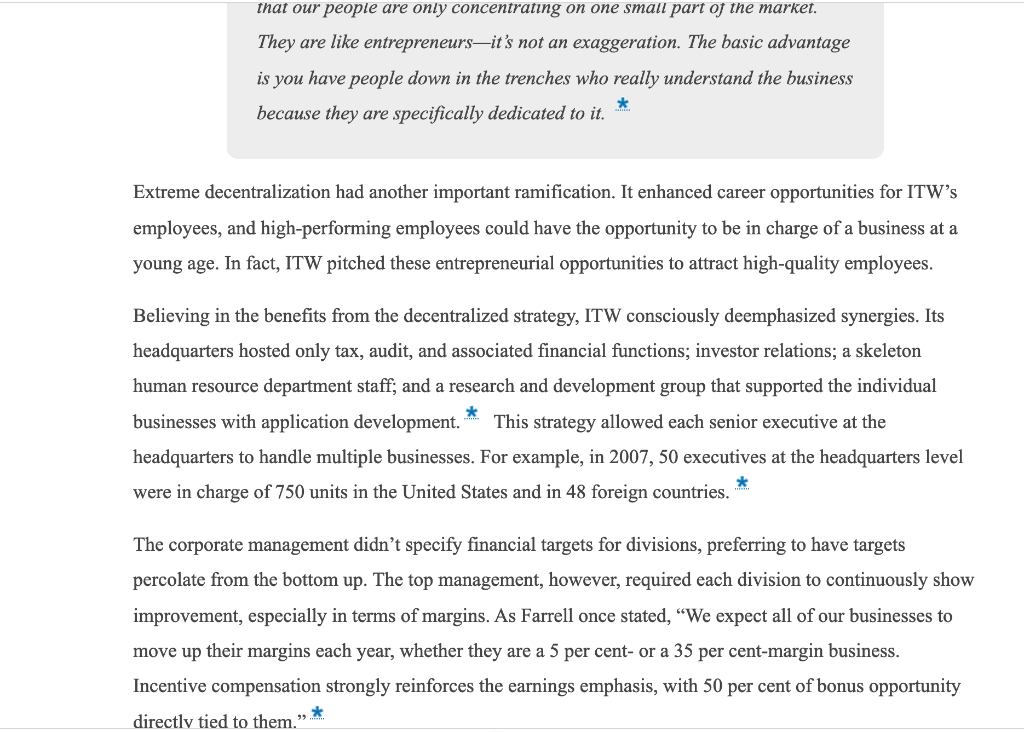

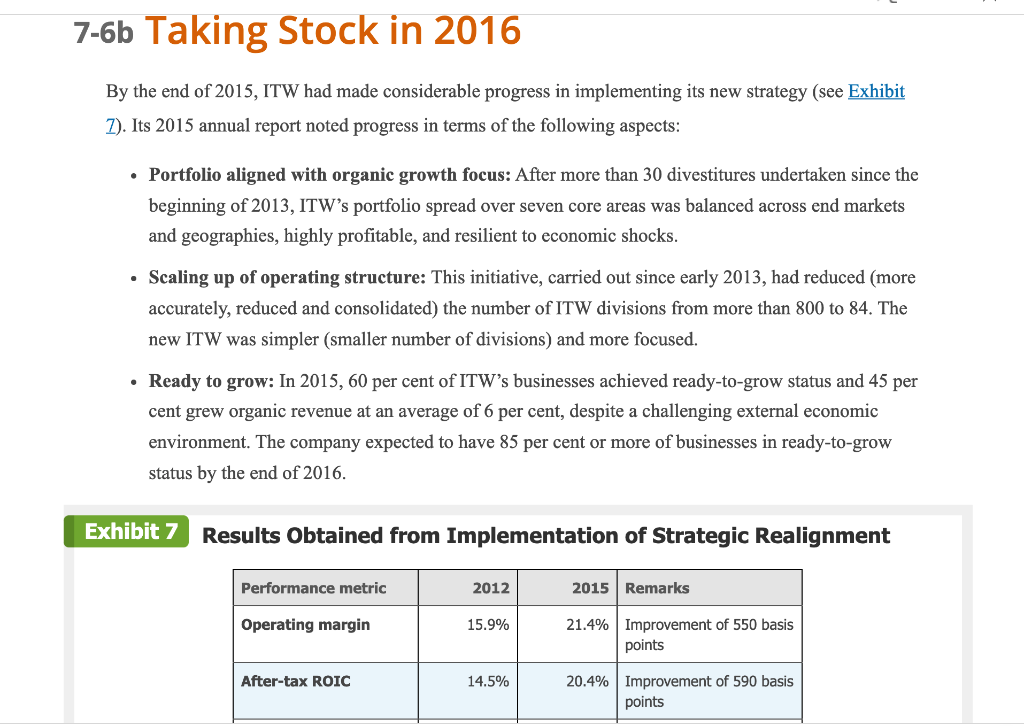

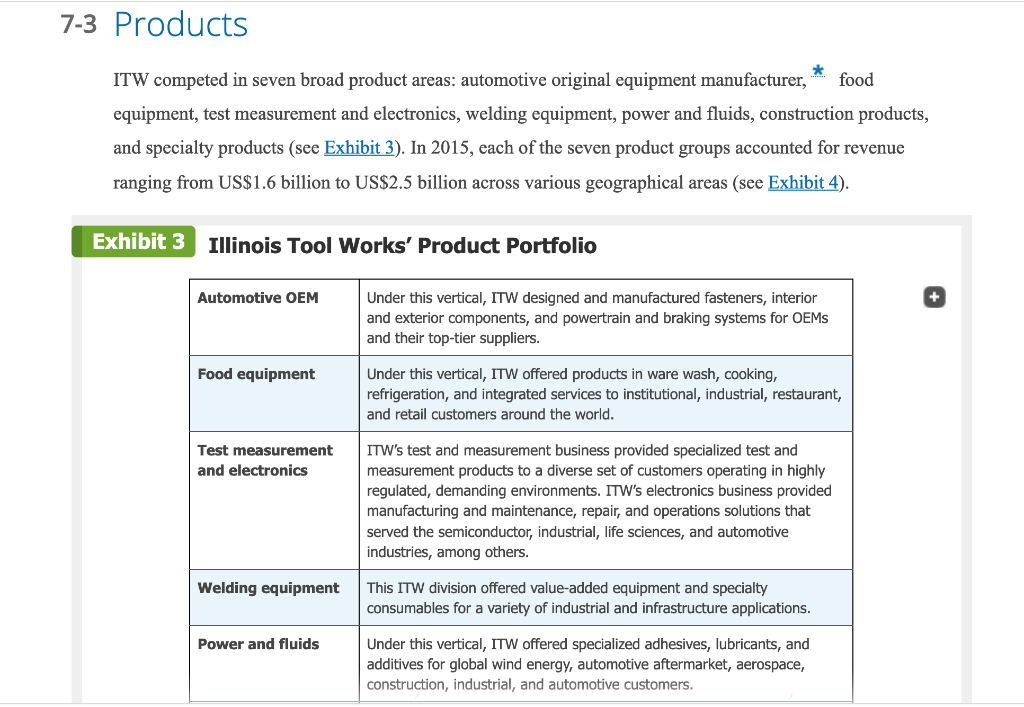

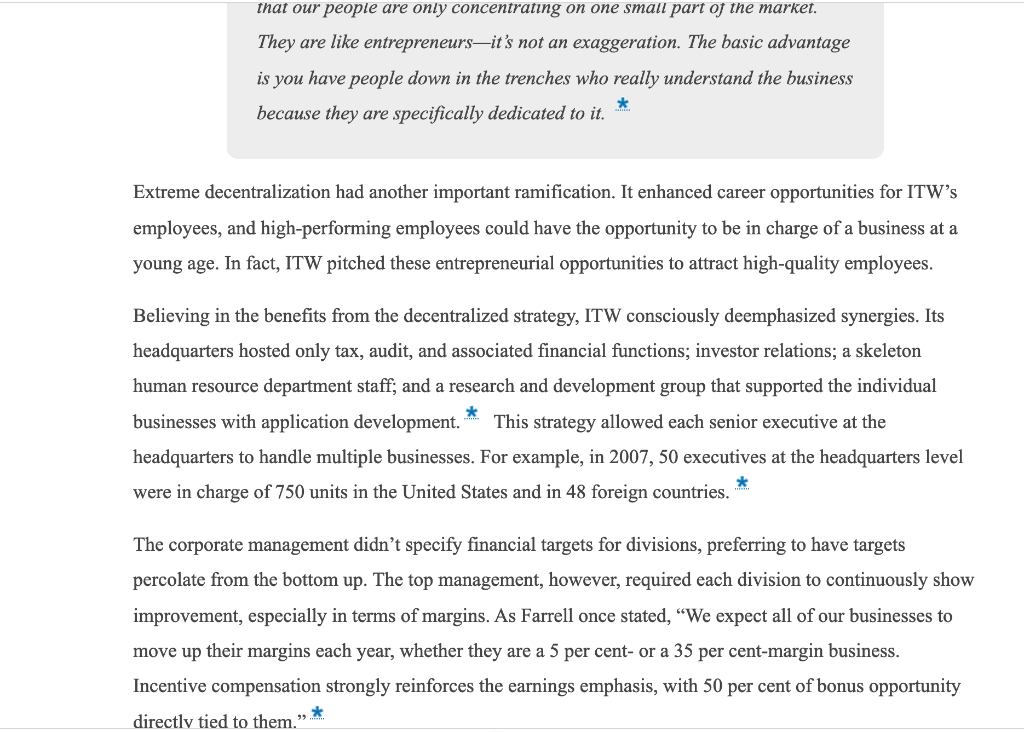

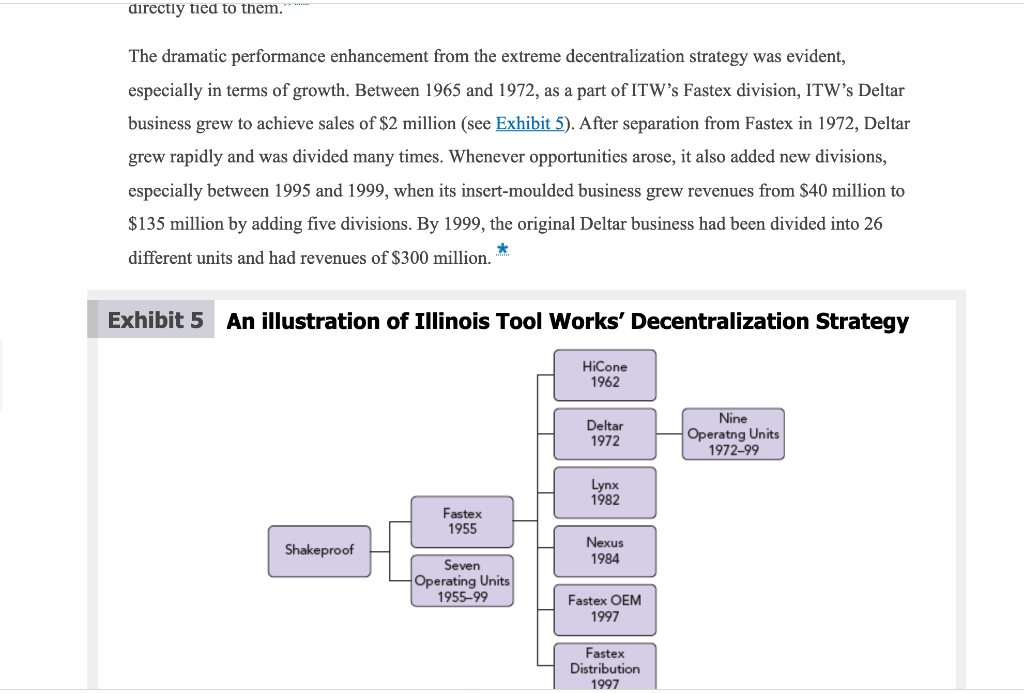

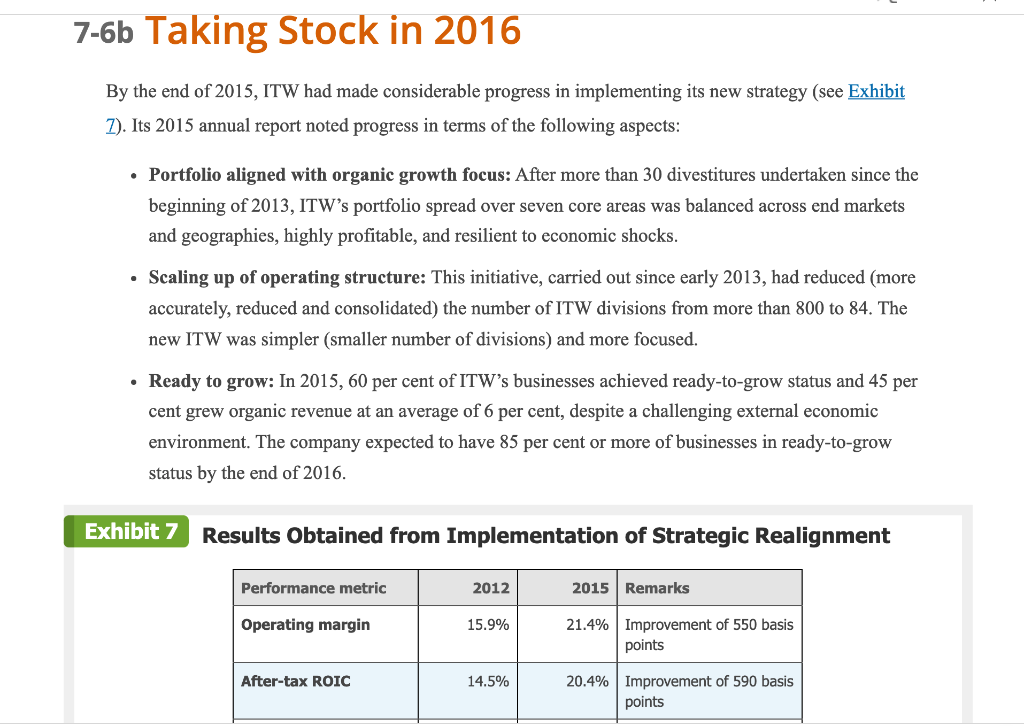

7-1 History In 1912, Frank W. England, Paul B. Goddard, Oscar T. Hogg, and Carl G. Olson formed ITW, a company that manufactured and sold metal-cutting tools. Supported by Chicago financier Byron L. Smith, the company quickly expanded to include products such as truck transmissions and pumps, which were in demand because of America's involvement in World War I. Before the end of the decade, three other companies were formedthe DeVilbiss Company, the Hobart Brothers Company, and Signodewhich would later become parts of ITW. The company continued to develop new engineered products, as well as grow its portfolio of products through acquisitions. Its engineering excellence earned the company representation on the War Production Board in World War II. In 1940, Harold B. Smith, the company's CEO at the time, implemented the strategy of decentralization, which was still a key ITW organizational strategy in 2016. Soon after its 50th anniversary, the company was listed on the New York Stock Exchange. During the 1960s, ITW further strengthened its position in the construction, industrial, and packaging markets, as well as expanding into international markets, which continued through the 1980s. Signode had by this time become a large multinational manufacturer of metal and plastic strapping, stretch film, industrial tape, application equipment, and related products. Its merger with ITW doubled the company's size. In 1996, Jim Farrell became chairman of ITW and refined the company's strategy towards numerous smaller acquisitions. * 7-2 The ITW Business Model By its own accounts, the ITW business model was composed of three elements: the 80/20 management process, customer-back innovation, and a decentralized entrepreneurial culture. The 80/20 management process implied focusing on the most rewarding areas such as the most profitable customers. The simplicity of this principle enabled ITW to concentrate its efforts, resources, and investments on key customers and products that were best positioned for profitable organic growth. One concrete example of implementation of the 80/20 principle was provided in the manufacturing of nails for wood-framed houses. ITW's analysis revealed that four types of nails accounted for 80 per cent of the volume and more than 20 other types of nails accounted for 20 per cent of the volume. To distinguish the products based on their salience, ITW started making the high-volume nails in different manufacturing cells from the other nails. Over time, ITW moved the high-volume nails to separate plants from the low-volume nails. Speer, the executive vice-president at the time, summarized the benefits of this approach as follows: If you keep them together, you end up compromising on both. If you separate them, you optimize both. * ITW's customer-back innovation placed an emphasis on solving customer problems. ITW had a strong intellectual property portfolio. Of its 16,000 granted and pending patents, 1,900 had been applied for in 2015 alone. ITW also took pride in applying technology expertise to solve customers' problems. For 2015 alone. ITW also took pride in applying technology expertise to solve customers' problems. For example, after realizing that smaller, fuel-efficient automobile engines generated higher levels of noise and vibration, ITW developed the WaveShear Isolation Springs to dampen noise and vibration. Another example of customer-back innovation, the click and collect food equipment initiative, offered customers who ordered perishable groceries online temperature-controlled lockers placed at strategic locations (proximate to customers) with the convenience of a flexible pick-up service, rather than having to wait for delivery. ITW promoted a decentralized-entrepreneurial culture. The company believed that its employees understood its business model, strategy, and core values, which allowed ITW to empower its business teams to make decisions and customize their approach to specific customers and end markets. In other words, ITW employees thought and acted like entrepreneurs and delivered results. 7-3 Products ITW competed in seven broad product areas: automotive original equipment manufacturer, food equipment, test measurement and electronics, welding equipment, power and fluids, construction products, and specialty products (see Exhibit 3). In 2015, each of the seven product groups accounted for revenue ranging from US$1.6 billion to US$2.5 billion across various geographical areas (see Exhibit 4). Exhibit 3 Illinois Tool Works' Product Portfolio Automotive OEM + Under this vertical, ITW designed and manufactured fasteners, interior and exterior components, and powertrain and braking systems for OEMs and their top-tier suppliers. Food equipment Under this vertical, ITW offered products in ware wash, cooking, refrigeration, and integrated services to institutional, industrial, restaurant, and retail customers around the world. Test measurement and electronics ITW's test and measurement business provided specialized test and measurement products to a diverse set of customers operating in highly regulated, demanding environments. ITW's electronics business provided manufacturing and maintenance, repair, and operations solutions that served the semiconductor, industrial, life sciences, and automotive industries, among others. Welding equipment This ITW division offered value-added equipment and specialty consumables for a variety of industrial and infrastructure applications. Power and fluids Under this vertical, ITW offered specialized adhesives, lubricants, and additives for global wind energy, automotive aftermarket, aerospace, construction, industrial, and automotive customers. 7-4 Decentralization Decentralization had been a key pillar of ITW's strategy since 1940. Until 2012, when Santi took over as CEO, the company practiced an extreme form of decentralization by acquiring small companies in most cases, and at other times, creating hundreds of small units from bigger companies that had either grown internally or had been acquired (e.g., Signode). Jim Farrell, an ITW CEO who had accelerated the implementation of the decentralization strategy, explained its advantage: "We're competitive in the marketplace. So run your consolidated model. It seems to me my costs are lower than yours with my decentralized model."* ITW's acquisitions followed by the implementation of a decentralization * strategy were referred to by Forbes magazine as a form of conquer and divide." The extreme practice of decentralization was also pursued with vigour under Farrell's successor Speer, who once aimed to have 1,000 small divisions under the ITW umbrella. Under the extreme decentralization strategy, ITW would typically consider splitting a business unit when the revenues reached the $50 million range. The resulting small size of the divisions would reduce the possibility of achieving economies of scale, but ITW found that it would enable the small divisions to be more focused and competitive. ITW's former vice-chairman Frank Ptak explained the concept as follows: We love competing against a big company, because their management teams don't have the same feel that our people have. It's not that we're smarter. It's that our people are only concentrating on one small part of the market. that our people are only concentrating on one small part of the market. They are like entrepreneursit's not an exaggeration. The basic advantage is you have people down in the trenches who really understand the business because they are specifically dedicated to it. * Extreme decentralization had another important ramification. It enhanced career opportunities for ITW's employees, and high-performing employees could have the opportunity to be in charge of a business at a young age. In fact, ITW pitched these entrepreneurial opportunities to attract high-quality employees. Believing in the benefits from the decentralized strategy, ITW consciously deemphasized synergies. Its headquarters hosted only tax, audit, and associated financial functions; investor relations; a skeleton human resource department staff; and a research and development group that supported the individual businesses with application development. This strategy allowed each senior executive at the headquarters to handle multiple businesses. For example, in 2007, 50 executives at the headquarters level were in charge of 750 units in the United States and in 48 foreign countries. * The corporate management didn't specify financial targets for divisions, preferring to have targets percolate from the bottom up. The top management, however, required each division to continuously show improvement, especially in terms of margins. As Farrell once stated, We expect all of our businesses to move up their margins each year, whether they are a 5 per cent- or a 35 per cent-margin business. Incentive compensation strongly reinforces the earnings emphasis, with 50 per cent of bonus opportunity directly tied to them." directly tied to them. The dramatic performance enhancement from the extreme decentralization strategy was evident, especially in terms of growth. Between 1965 and 1972, as a part of ITW's Fastex division, ITW's Deltar business grew to achieve sales of $2 million (see Exhibit 5). After separation from Fastex in 1972, Deltar grew rapidly and was divided many times. Whenever opportunities arose, it also added new divisions, especially between 1995 and 1999, when its insert-moulded business grew revenues from $40 million to $135 million by adding five divisions. By 1999, the original Deltar business had been divided into 26 different units and had revenues of $300 million. Exhibit 5 An illustration of Illinois Tool Works' Decentralization Strategy Hicone 1962 Deltar 1972 Nine Operatng Units 1972-99 Lynx 1982 Fastex 1955 Shakeproof Nexus 1984 Seven Operating units 1955-99 Fastex OEM 1997 Fastex Distribution 1997 7-5 Acquisitions ITW had always undertaken acquisitions. However, under CEOs Farrell and Speer, ITW implemented a strategy of undertaking up to 3050 acquisitions per year, in some years. ITW typically focused on targets valued under $100 million that were available at less than 1.1 times the book value (see Exhibits 1 and 6). * Speaking about ITW's preference for small acquisitions over large acquisitions, former CFO Jon Kinney once said, When you acquire just one large business, all the assumptions you made about it and what ITW can do with it had better be correct. You're putting all your eggs in one basket. In rare cases, ITW made large acquisitions and divided the large acquired company into many small pieces, as in the case of Signode, which was acquired for $800 million in 1986 and then divided into 50 companies. * * Exhibit 6 Illinois Tool Works' acquisition strategy before 2013 1000 100 10 1 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 28 36 32 45 29 21 28 24 22 53 52 Number of Deals Average Acquisition Size in US$ Millions 15 23 11922 192 12 26 27 32 19 Number of Deals Average Acquisition Size in US$ Millions ITW's acquisitions strategy was based on a number of rules of thumb. It sought targets that filled gaps in its capabilities, such as complementary product expertise or relationships with important customers. The acquisitions were also typically initiated by middle managers, rather than flowing down from the top, which ensured that implementation issues would be taken into account before the acquisition, instead of afterwards. Recognizing that a typical middle manager would likely lack the necessary skills to find or undertake acquisitions, former CEO Speer implemented two-day acquisition workshops for business unit * managers. ITW also tried to minimize the negative impact on the morale of target employees post- acquisition by retaining the identity of the target company. It would only stipulate that target companies attempt to integrate at a broad level (e.g., by using a company-wide accounting package), and seek simplicity and operational excellence through deploying the 80/20 principle. Finally, ITW was careful not to use acquisitions for novel situations, such as entering new countries. It developed its own knowledge- base about a country by establishing owned-operations before embarking on acquisitions. In 2005, out of ITW's 21 businesses in China, only one had been through an acquisition, and that one was converted from a joint venture. At the same time, only two of its 11 businesses in India had started out as joint ventures and were subsequently converted into wholly-owned subsidiaries. * In general, the acquired companies' employees and management seemed to appreciate the benefits of ITW's approach. For example, in 2005, ITW acquired Permatex; the next year, Permatex's marketing director Tony Battaglia commented on the acquisition: 7-5a ITW's Acquisition of Precor: An Illustration of Its Acquisition Strategy and Approach to Operational Excellence ITW's acquisition of Precor served as an excellent example of the transformation it brought about in acquired companies. Since its inception in 1983, Precor had gained a reputation as an innovative and leading manufacturer of exercise equipment in the United States and internationally. Despite its innovation and market-leading revenues, Precor exhibited poor performance with regard to a variety of metrics at the time of its acquisition by ITW. Its on-time shipments stood at a dismal 42 per cent. It had a rather unwieldy supply chain, consisting of as many as 3,000 suppliers, with most suppliers accounting for small volumes, and its employee turnover was high. ITW implemented a number of its usual policies at Precor: the 80/20 rule, product line simplification, rationalization of manufacturing plants and suppliers, and workflow simplification. Within three years, the new strategy had produced spectacular results. The percentage of on-time deliveries improved from 42 to 91, headcount was reduced from 952 to 456, and the number of plants was reduced from seven to five without negatively affecting production. Inventory levels went down by 40 per cent and warranty claims by 57 per cent, resulting in savings of millions of dollars. After bringing about a dramatic improvement in Precor's financial results, ITW sold Precor in 2002 for 180 million to Amer Sports, based in Helsinki, 7-6 Organization and Human Resources Policies ITW implemented a number of organizational and human resources policies that were aligned with its broader enterprise-level strategy, as well as other functional-level policies. Throughout its history, ITW had emphasized continuity and stability in terms of its leadership. When Santi assumed the role of CEO, he was only the sixth CEO in the company's 100-year history, implying an average tenure of more than a decade. Many of the CEOs had also previously worked in ITW for a long time, and thus were steeped in the ITW culture and tradition. For example, Santi had spent his entire working career at ITW. Since 1995, ITW had also adopted a tradition that each incoming CEO be presented with a crystal frog wearing a golden crown and bearing the name of prior CEOs, signalling to the incoming CEO that the counsel of previous CEOs was always available. ITW's culture was informal and relationship-driven, as described by Santi: It's a lot of conversations. It's not a lot of memos. It's not a lot of PowerPoints, but it's a lot of belly-to-belly conversations and creating * that alignment, engagement, and enthusiasm that turns this culture loose." Echoing similar thoughts, former CEO Farrell had once said: I want to see your eyes, I want to see if you're getting it. If you're not, I haven't communicated very well. And I clearly can't do that via e-mail. In our organization, we rely so much on trusting our people to do the right things that trying to talk to them electronically would diminish that personal things that trying to talk to them electronically would diminish that personal communication and compromise our business success. Many other executives described ITW's culture as highly egalitarian and down-to-earth. ITW's headquarters were described by an article in the Crain's Chicago Business as a cluster of nondescript low-rise buildings, [where) there is no executive cafeteria and the only reserved parking spaces are for the food and mail trucks. Former ITW vice-chairman Ptak once remarked: You realized that there was a part of business and a part of making money that wasn't so draconian. That you could be nice. 99 ..... 7-6a Retooling ITW's Strategy In January 2012, ITW reached an agreement with activist investor Relational Investors (Relational), which had acquired a small stake in ITW. According to the agreement, Relational's principal and co-founder David Batchelder would join the ITW board of directors. Relational had suggested a strategy makeover for ITW consisting of centralizing its operations and divestment of a number of its small divisions. Many analysts agreed with Relational's suggestions primarily because ITW's strategy of small acquisitions and extreme decentralization had resulted in lagging returns versus peers since the onset of the global recession in 2007. After assuming the role of CEO in November 2012, Santi moved quickly to implement a new strategy based on divestment of small divisions that sold commoditized products, or that were likely to grow slowly. 7-6b Taking Stock in 2016 By the end of 2015, ITW had made considerable progress in implementing its new strategy (see Exhibit 7). Its 2015 annual report noted progress in terms of the following aspects: Portfolio aligned with organic growth focus: After more than 30 divestitures undertaken since the beginning of 2013, ITW's portfolio spread over seven core areas was balanced across end markets and geographies, highly profitable, and resilient to economic shocks. Scaling up of operating structure: This initiative, carried out since early 2013, had reduced (more accurately, reduced and consolidated) the number of ITW divisions from more than 800 to 84. The new ITW was simpler (smaller number of divisions) and more focused. Ready to grow: In 2015, 60 per cent of ITW's businesses achieved ready-to-grow status and 45 per cent grew organic revenue at an average of 6 per cent, despite a challenging external economic environment. The company expected to have 85 per cent or more of businesses in ready-to-grow status by the end of 2016. Exhibit 7 Results obtained from Implementation of Strategic Realignment Performance metric 2012 2015 Remarks Operating margin 15.9% 21.4% Improvement of 550 basis points After-tax ROIC 14.5% 20.4% Improvement of 590 basis points 7-7 The Road Ahead While ITW and Santi had much to be proud of with regard to a long history of accomplishments and recent success in reorienting its strategy, respectively, many challenges remained. Santi's and ITW's biggest challenge was related to achieving continued growth after abandoning its strategies of numerous small acquisitions and extreme decentralization. The challenge came in two forms. First, ITW would have to generate a good portion of its future growth in revenues and profits organically rather than through acquisitions. Although the portfolio had been streamlined over the past three years, a period over which investors had tolerated negative revenue growth, and it had resulted in better margins, future organic growth seemed critical. This was especially important because it would be difficult to continuously improve margins through cost cutting and operational improvements. Secondly, ITW had changed its acquisition strategy from numerous small acquisitions to "needle-moving large acquisitions. Targets in larger acquisitions were less likely be under the radar of other potential acquirers, and hence, less likely to be undervalued. Unlike small companies, which ITW had historically acquired, the opportunities to implement operations improvements strategies were also likely to be limited for larger targets because many companies in the latter category would already have efficient operations in place. Going forward, ITW also had to make important choices about resource allocation across product groups, based on their past performance and future prospects. In summary, Santi and ITW had to make appropriate decisions for continued superior performance