Question: 2) For each of the following groups, discuss whether each was better-off or worse-off after the launch of Napster and why: 1) Consumers; 2) Super-star

2) For each of the following groups, discuss whether each was better-off or worse-off after the launch of Napster and why: 1) Consumers; 2) Super-star artists; 3) Unknown artists; 4) One of the big record labels; 5) Music stores. (10 marks) 3) Using all elements from the Strategy Triangle from our course, describe Apple Inc.s initial digital

music strategy with regards to its launch of the iPod and iTunes.

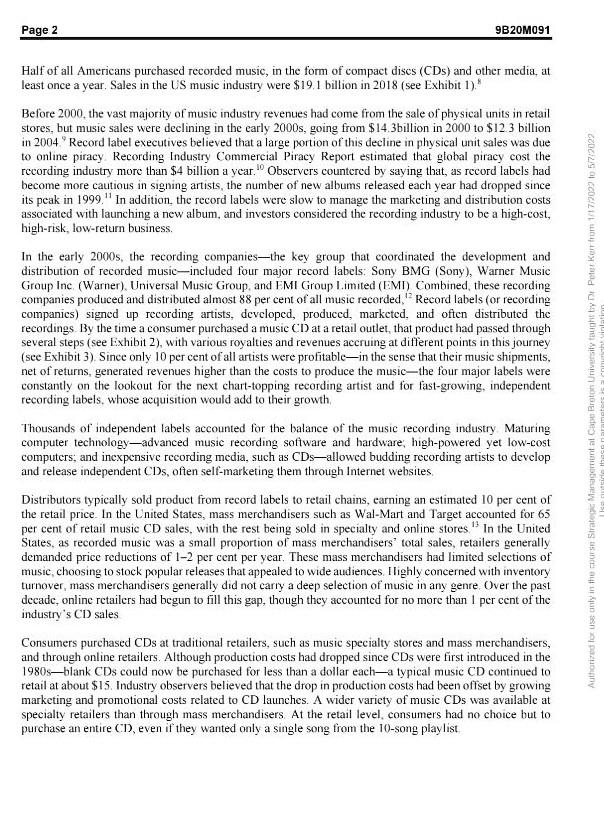

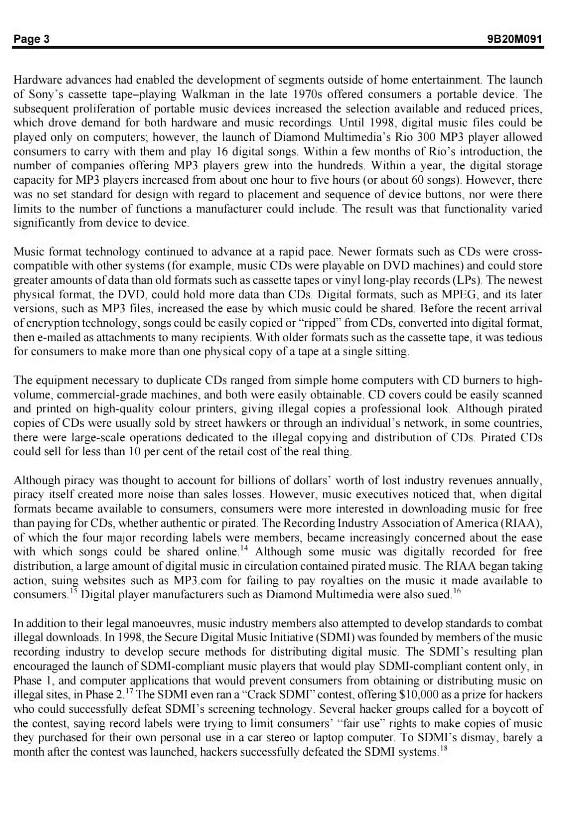

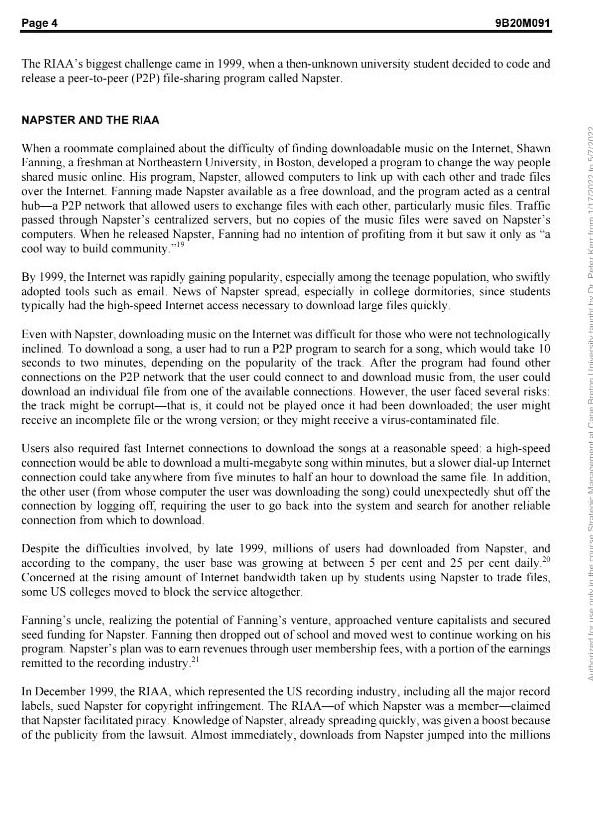

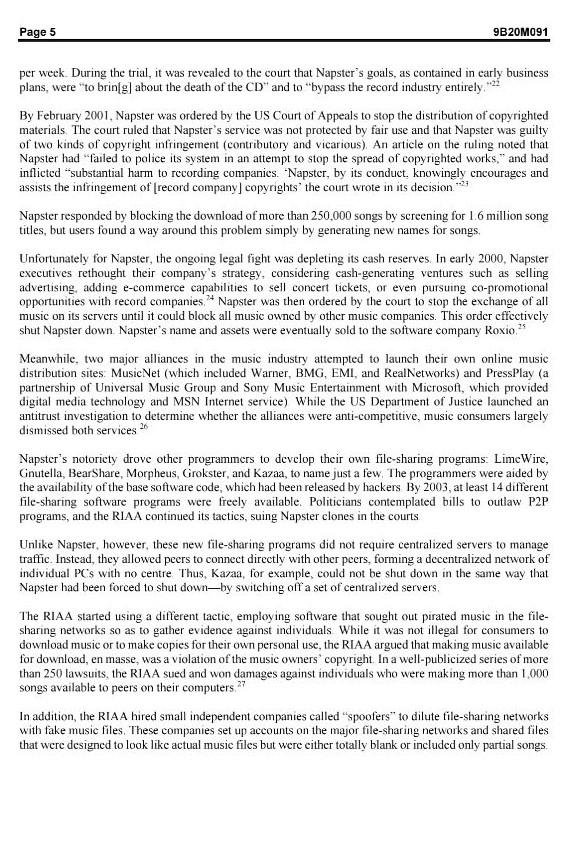

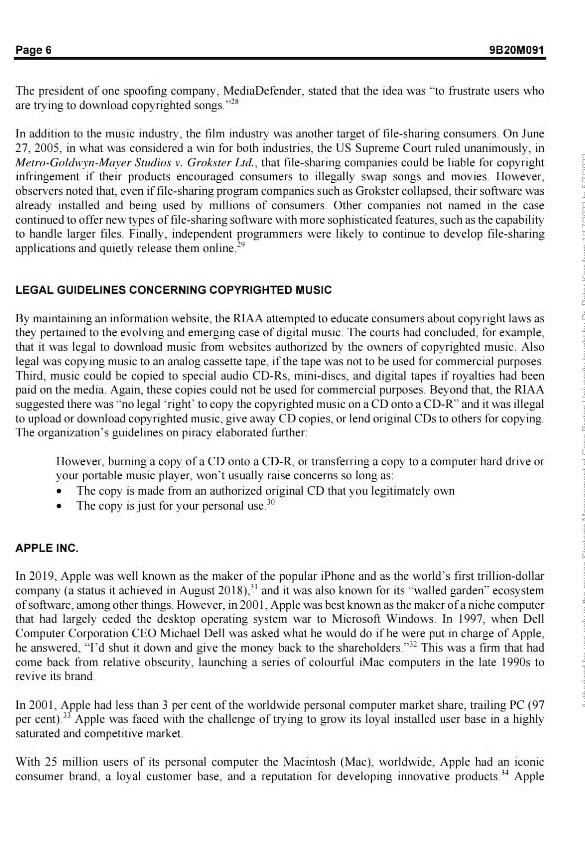

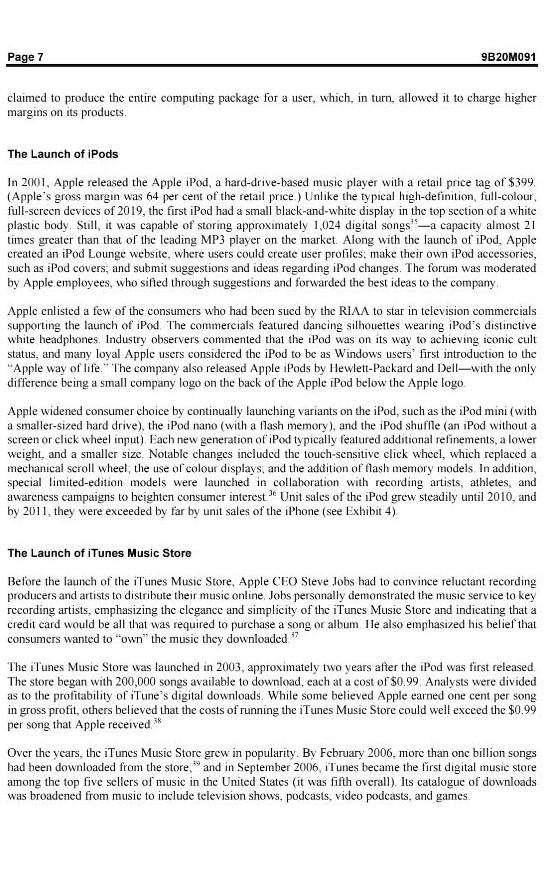

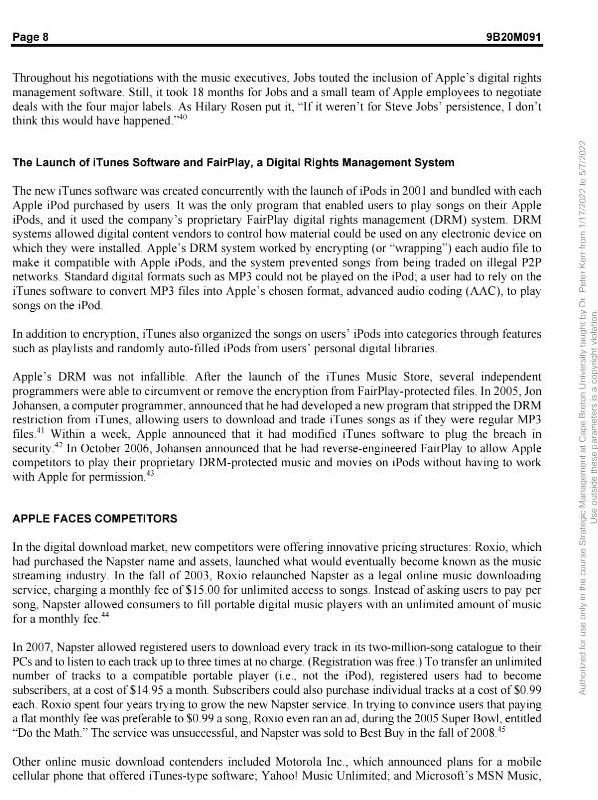

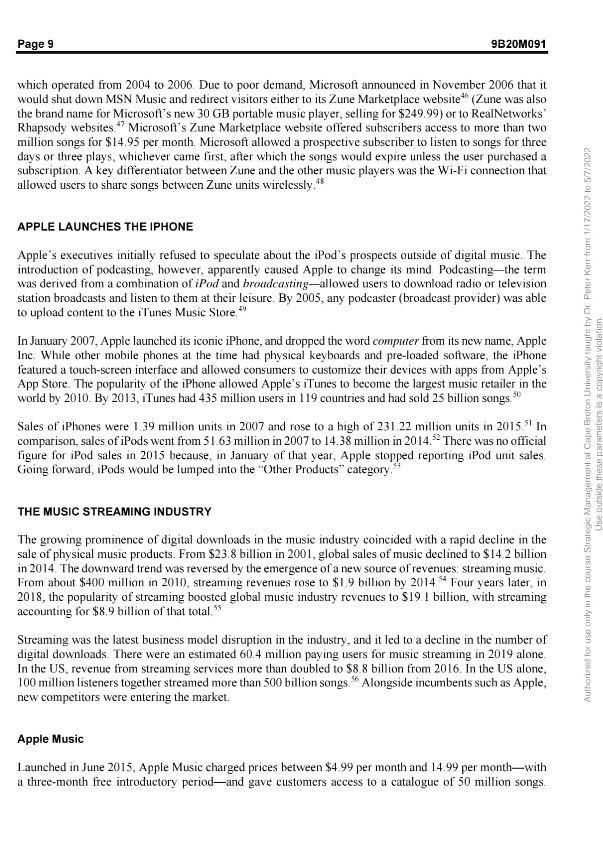

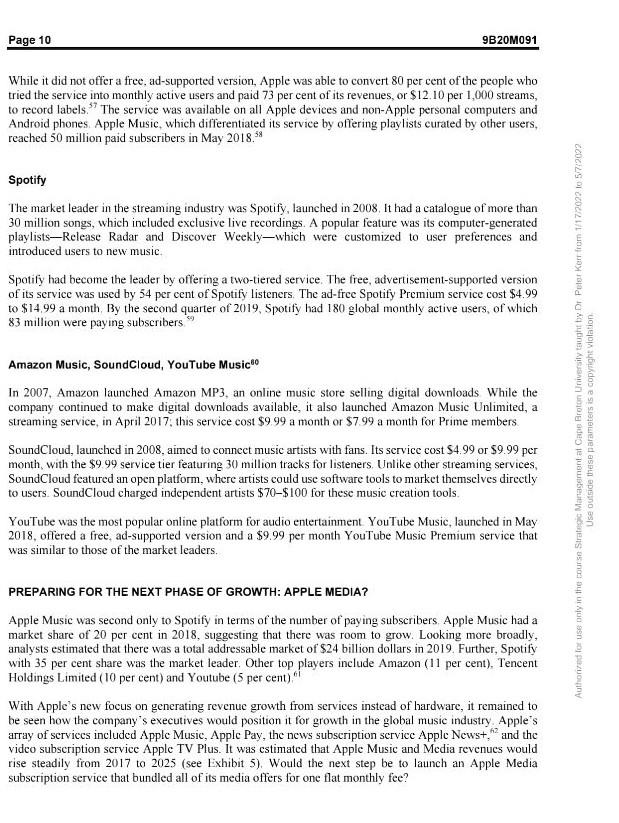

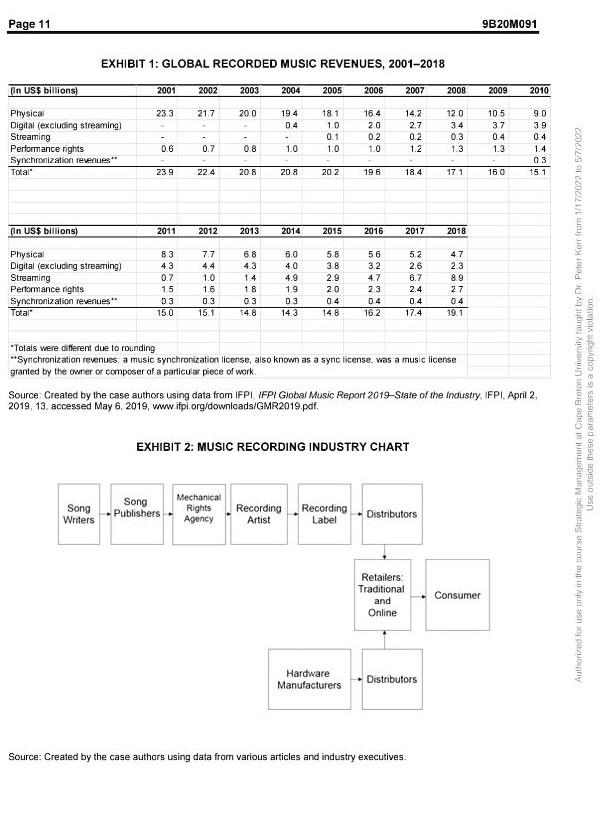

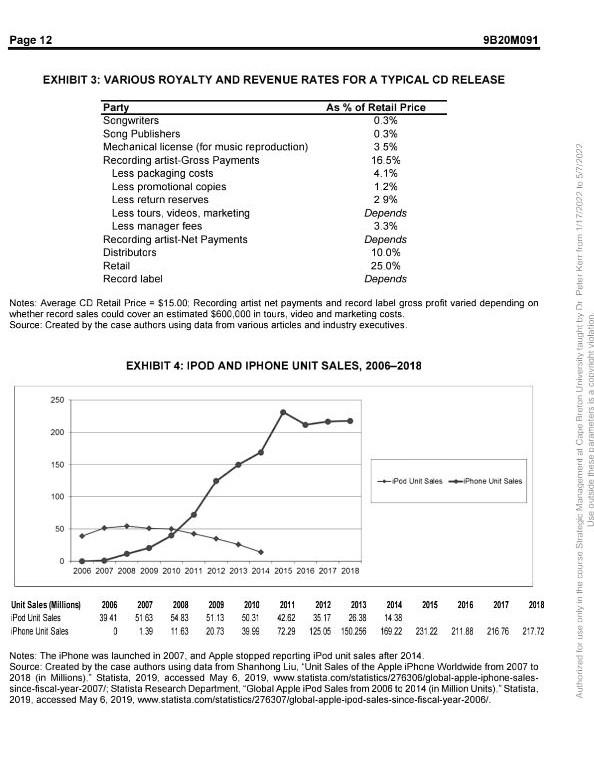

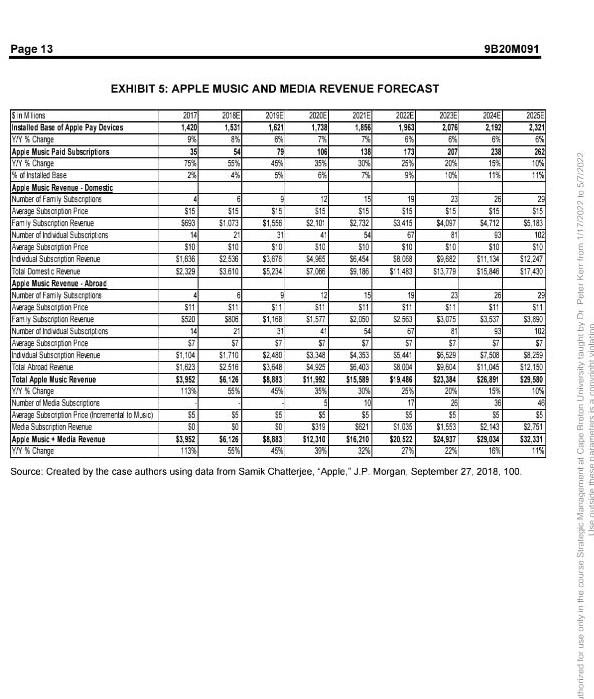

Ivey Publishing 9B20M091 APPLE AND THE MUSIC INDUSTRY Kan Mark wrote this case under the supervision of Professor Mary Crossan solely to provide material for class discussion. The authors do not intend to Wustrate either effective or ineffective handling of a managerial situation. The authors may have disguised certain names and other identifying information to protect confidentiality This publication may not be transmitted photocopied, digitized, or otherwise reproduced in any form or by any means without the permission of the copyright holder Reproduction of this material is not covered under authorization by any reproduction rights organization. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, contact Ivey Publishing, Ivey Business School, Western University. London, Ontario, Canada, NEG ONT: (0519.661.3208(e) cases ivey.ca, www.iveycases com. Our goal is to publish materials of the highest quality: submit any errata to publishcases wey.ca. Copyright 2020, Ivey Business School Foundation Version: 2020-05-os On November 1, 2018, a headline in the Financial Times announced, Apple to stop revcaling unit sales sparking peak iPhone fears," and investors sold stock in Apple Inc. (Apple), pushing its value down by almost 7 percent. Observers wondered if slowing hardware sales would spell trouble for Apple's position in the streaming music industry, where despite its dominance in hardware, its brand image, and its large cash cushion, the company continued to lag behind market leader Spotify AB (Spotify) in terms of its number of paid subscribers. Could Apple reinvent itself again in the music industry, as it had done in the past? Apple had once been a maverick in the global music industry, striking a deal to distribute downloadable music from its iTunes Store and growing market share with the launch of its iPod in 2001. The iPod had at one point had a 92 per cent share of the music player market.' before competitors such as Microsoft Corporation (Microsoft) and SanDisk entered the industry and drove the iPod's share down to 71 per cent Then the company launched the iPhone in January 2007, reigniting growth in the sale of digital music downloads But then the disrupter was disrupted. The emergence of streaming music in 2005 seemed to take the incumbents by surprise By 2019, streaming was the largest segment in the music industry by revenues, accounting for US$8 9 billion in sales out of a $19.1 billion global market. There were new players, including Spotify, Amazon.com Inc. (Amazon), Google LLC, and Pandora' It seemed that change was the only constant in the global music industry. Apple had led the initial break from the past and had profited immensely from it. What would Apple need to do to continue to play a leading role in the music industry's future? Authorized for use only in the course Strategy Management at Cape Breton University taughty Di Peter Kerom 1/17/2022 10 5/7/2022 lisensie sanatoris amint vinntinn THE MUSIC RECORDING INDUSTRY Recorded music, as a form of entertainment, could be encountered anywhere in North America and, indeed, in much of the world Thousands of radio stations broadcast song lists interspersed with commercials, televised music videos were available on music channels such as MTV; and public venues such as shopping malls, bars. and restaurants played background music Music tastes among consumers spanned a variety of options from classic rock, heavy metal, rap, and country to other existing and emerging genres. Although only a fraction of the countless recording artists achieved success and fame, the perceived glamour of the music industry continued to draw large numbers of aspiring recording artists, all eager to become the next star Page 2 9B20M091 Half of all Americans purchased recorded music, in the form of compact discs (CDs) and other media, at least once a year. Sales in the US music industry were $19.1 billion in 2018 (see Exhibit 1). Before 2000, the vast majority of music industry revenues had come from the sale of physical units in retail stores, but music sales were declining in the early 2000s, going from $14.3billion in 2000 to $12.3 billion in 2004 Record label executives believed that a large portion of this decline in physical unit sales was due to online piracy Recording Industry Commercial Piracy Report estimated that global piracy cost the recording industry more than $4 billion a year." Observers countered by saying that, as record labels had become more cautious in signing artists, the number of new albums released each year had dropped since its peak in 1999." In addition, the record labels were slow to manage the marketing and distribution costs associated with launching a new album, and investors considered the recording industry to be a high-cost, high-risk, low-return business In the early 2000s, the recording companiesthe key group that coordinated the development and distribution of recorded music-included four major record labels: Sony BMG (Sony), Warner Music Group Inc (Warner). Universal Music Group, and EMI Group Limited (EMI) Combined these recording companies produced and distributed almost 88 per cent of all music recorded." Record labels (or recording companics) signed up recording artists, developed, produced, marketed, and often distributed the recordings. By the time a consumer purchased a music CD at a retail outlet that product had passed through several steps (see Exhibit 2), with various royalties and revenues accruing at different points in this journey (see Exhibit 3). Since only 10 per cent of all artists were profitablein the sense that their music shipments, net of returns, generated revenues higher than the costs to produce the musicthe four major labels were constantly on the lookout for the next chart-topping recording artist and for fast-growing, independent recording labels, whose acquisition would add to their growth Thousands of independent labels accounted for the balance of the music recording industry Maturing computer technology-advanced music recording software and hardware, high-powered yet low-cost computers, and inexpensive recording media, such as CDsallowed budding recording artists to develop and release independent CDs, often self-marketing them through Internet websites Distributors typically sold product from record labels to retail chains, earning an estimated 10 per cent of the retail price in the United States, mass merchandisers such as Wal-Mart and Target accounted for 65 per cent of retail music CD sales, with the rest being sold in specialty and online stores in the United States, as recorded music was a small proportion of mass merchandisers' total sales, retailers generally demanded price reductions of 1-2 per cent per year. These mass merchandisers had limited selections of music choosing to stock popular releases that appealed to wide audiences llighly concerned with inventory turnover, mass merchandisers generally did not carry a deep selection of music in any genre. Over the past decade, online retailers had begun to fill this gap, though they accounted for no more than 1 per cent of the industry's CD sales Consumers purchased CDs at traditional retailers, such as music specialty stores and mass merchandisers, and through online retailers. Although production costs had dropped since CDs were first introduced in the 1980s-blank CDs could now be purchased for less than a dollar eacha typical music CD continued to retail at about $15. Industry observers believed that the drop in production costs had been offset by growing marketing and promotional costs related to CD launches. A wider variety of music CDs was available at specialty retailers than through mass merchandisers At the retail level, consumers had no choice but to purchase an entire CD, even if they wanted only a single song from the 10-song playlist Authorized for use only in the nursin Strategic Management al Cape Breton University taughty Di Pote Kerr from 1/17/2032 10 5/7/2022 Page 3 9B20M091 Hardware advances had enabled the development of segments outside of home entertainment. The launch of Sony's cassette tape-playing Walkman in the late 1970s offered consumers a portable device. The subsequent proliferation of portable music devices increased the selection available and reduced prices, which drove demand for both hardware and music recordings Until 1998, digital music files could be played only on computers, however, the launch of Diamond Multimedia's Rio 300 MP3 player allowed consumers to carry with them and play 16 digital songs within a few months of Rio's introduction, the number of companies offering MP3 players grew into the hundreds Within a year, the digital storage capacity for MP3 players increased from about one hour to five hours (or about 60 songs). However, there was no set standard for design with regard to placement and sequence of device buttons, nor were there limits to the number of functions a manufacturer could include The result was that functionality varied significantly from device to device Music format technology continued to advance at a rapid pace. Newer formats such as CDs were cross- compatible with other systems (for example, music CDs were playable on DVD machines) and could store greater amounts of data than old formats such as cassette tapes or vinyl long-play records (LPs) The newest physical format, the DVD, could hold more data than CDs Digital formats, such as MPEG, and its later versions, such as MP3 files, increased the ease by which music could be shared Before the recent arrival of encryption technology, songs could be casily copied or ripped" from CDs, converted into digital format, then e-mailed as attachments to many recipients. With older formats such as the cassette tape, it was tedious for consumers to make more than one physical copy of a tape at a single sitting The equipment necessary to duplicate CDs ranged from simple home computers with CD burners to high- volume, commercial-grade machines, and both were easily obtainable CD covers could be easily scanned and printed on high-quality colour printers, giving illegal copies a professional look Although pirated copies of CDs were usually sold by street hawkers or through an individual's network, in some countries, there were large-scale operations dedicated to the illegal copying and distribution of CDs Pirated CDs could sell for less than 10 per cent of the retail cost of the real thing Although piracy was thought to account for billions of dollars worth of lost industry revenues annually, piracy itself created more noise than sales losses. However, music executives noticed that, when digital formats became available to consumers, consumers were more interested in downloading music for free than paying for CDs, whether authentic or pirated. The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), of which the four major recording labels were members, became increasingly concerned about the ease with which songs could be shared online. Although some music was digitally recorded for free distribution, a large amount of digital music in circulation contained pirated music. The RIAA began taking action, suing websites such as MP3.com for failing to pay royalties on the music it made available to consumers Digital player manufacturers such as Diamond Multimedia were also sued In addition to their legal manoeuvres, music industry members also attempted to develop standards to combat illegal downloads, In 1998, the Secure Digital Music Initiative (SDMI) was founded by members of the music recording industry to develop secure methods for distributing digital music. The SDMI's resulting plan encouraged the launch of SDMI-compliant music players that would play SDMI-compliant content only, in Phase 1 and computer applications that would prevent consumers from obtaining or distributing music on illegal sites, in Phase 2.'? The SDMI even ran a "Crack SDMI"contest, offering $10,000 as a prize for hackers who could successfully defcat SDMI's screening technology. Several hacker groups called for a boycott of the contest, saying record labels were trying to limit consumers "fair use" rights to make copies of music they purchased for their own personal use in a car stereo or laptop computer. To SDMI's dismay, barely a month after the contest was launched, hackers successfully defeated the SDMI systems." Page 4 9B20M091 The RIAA's biggest challenge came in 1999, when a then-unknown university student decided to code and release a peer-to-peer (P2P) file-sharing program called Napster, 222 NAPSTER AND THE RIAA When a roommate complained about the difficulty of finding downloadable music on the Internet, Shawn Fanning, a freshman at Northeastern University, in Boston developed a program to change the way people shared music online. His program, Napster, allowed computers to link up with cach other and trade files over the Internet. Fanning made Napster available as a free download, and the program acted as a central huba P2P network that allowed users to exchange files with each other, particularly music files. Traffic passed through Napster's centralized servers, but no copies of the music files were saved on Napster's computers. When he released Napster, Fanning had no intention of profiting from it but saw it only as a cool way to build community. -1 By 1999, the Internet was rapidly gaining popularity, especially among the teenage population, who swiftly adopted tools such as email News of Napster spread, especially in college dormitories, since students typically had the high-speed Internet access necessary to download large files quickly Even with Napster, downloading music on the Internet was difficult for those who were not technologically inclined. To download a song, a user had to run a P2P program to search for a song, which would take 10 seconds to two minutes, depending on the popularity of the track. After the program had found other connections on the P2P network that the user could connect to and download music from the user could download an individual file from one of the available connections However, the user faced several risks: the track might be corruptthat is, it could not be played once it had been downloaded the user might receive an incomplete file or the wrong version or they might receive a virus-contaminated file. Users also required fast Internet connections to download the songs at a reasonable speed a high-speed connection would be able to download a multi-megabyte song within minutes, but a slower dial-up Internet connection could take anywhere from five minutes to half an hour to download the same file In addition, the other user (from whose computer the user was downloading the song) could unexpectedly shut off the connection by logging off, requiring the user to go back into the system and search for another reliable connection from which to download Despite the difficulties involved, by late 1999, millions of users had downloaded from Napster, and according to the company, the user base was growing at between 5 per cent and 25 per cent daily.20 Concerned at the rising amount of Internet bandwidth taken up by students using Napster to trade files, some US colleges moved to block the service altogether. Fanning's uncle, realizing the potential of Fanning's venture, approached venture capitalists and secured seed funding for Napster. Fanning then dropped out of school and moved west to continue working on his program Napster's plan was to earn revenues through user membership fees, with a portion of the earnings remitted to the recording industry. In December 1999, the RIAA, which represented the US recording industry, including all the major record labels, sued Napster for copyright infringement. The RIAA-of which Napster was a member-claimed that Napster facilitated piracy Knowledge of Napster, already spreading quickly, was given a boost because of the publicity from the lawsuit. Almost immediately, downloads from Napster jumped into the millions Page 5 9B20M091 per week. During the trial, it was revealed to the court that Napster's goals, as contained in early business plans, were "to brin[g] about the death of the CD" and to "bypass the record industry entirely. By February 2001, Napster was ordered by the US Court of Appeals to stop the distribution of copyrighted materials The court ruled that Napster's service was not protected by fair use and that Napster was guilty of two kinds of copyright infringement contributory and vicarious). An article on the ruling noted that Napster had failed to police its system in an attempt to stop the spread of copyrighted works," and had inflicted "substantial harm to recording companies. "Napster, by its conduct knowingly encourages and assists the infringement of (record company copyrights the court wrote in its decision Napster responded by blocking the download of more than 250,000 songs by screening for 1.6 million song titles, but users found a way around this problem simply by generating new names for songs, Unfortunately for Napster, the ongoing legal fight was depleting its cash reserves. In early 2000, Napster cxecutives rethought their company's strategy, considering cash-generating ventures such as selling advertising, adding e-commerce capabilities to sell concert tickets, or even pursuing co-promotional opportunities with record companies Napster was then ordered by the court to stop the exchange of all music on its servers until it could block all music owned by other music companies. This order effectively shut Napster down Napster's name and assets were eventually sold to the software company Roxio." Meanwhile, two major alliances in the music industry attempted to launch their own online music distribution sites. MusicNet (which included Warner, BMG, EMI, and RealNetworks) and Press Play (a partnership of Universal Music Group and Sony Music Entertainment with Microsoft, which provided digital media technology and MSN Internet service) While the US Department of Justice launched an antitrust investigation to determine whether the alliances were anti-competitive, music consumers largely dismissed both services Napster's notoriety drove other programmers to develop their own file sharing programs: LimeWire, Gnutella, BearShare, Morpheus, Grokster, and Kazaa, to name just a few. The programmers were aided by the availability of the base software code, which had been released by hackers By 2003, at least 14 different file sharing software programs were freely available. Politicians contemplated bills to outlaw P2P programs, and the RIAA continued its tactics, suing Napster clones in the courts Unlike Napster, however, these new file-sharing programs did not require centralized servers to manage traffic. Instead, they allowed peers to connect directly with other peers, forming a decentralized network of individual PCs with no centre Thus, Kazaa, for example, could not be shut down in the same way that Napster had been forced to shut downby switching off a set of centralized servers. The RIAA started using a different tactic, employing software that sought out pirated music in the file- sharing networks so as to gather evidence against individuals. While it was not illegal for consumers to download music or to make copies for their own personal use, the RIAA argued that making music available for download, en masse, was a violation of the music owners' copyright. In a well-publicized series of more than 250 lawsuits, the RIAA sued and won damages against individuals who were making more than 1,000 songs available to peers on their computers In addition, the RIAA hired small independent companies called "spoofers to dilute file-sharing networks with fake music files. These companies set up accounts on the major file-sharing networks and shared files that were designed to look like actual music files but were either totally blank or included only partial songs Page 6 9B20M091 The president of one spoofing company. MediaDefender, stated that the idea was "to frustrate users who are trying to download copyrighted songs *** In addition to the music industry, the film industry was another target of file sharing consumers On June 27. 2005, in what was considered a win for both industries, the US Supreme Court ruled unanimously, in Metro-Goldwyn-Maver Studios v. Grokster Ltd., that file sharing companies could be liable for copyright infringement if their products encouraged consumers to illegally swap songs and movies. However, observers noted that, cven if file-sharing program companies such as Grokster collapsed, their software was already installed and being used by millions of consumers. Other companies not named in the case continued to offer new types of file sharing software with more sophisticated features, such as the capability to handle larger files. Finally, independent programmers were likely to continue to develop file-sharing applications and quietly release them online, LEGAL GUIDELINES CONCERNING COPYRIGHTED MUSIC By maintaining an information website, the RIAA attempted to educate consumers about copyright laws as they pertained to the evolving and emerging case of digital music. The courts had concluded, for example, that it was legal to download music from websites authorized by the owners of copyrighted music. Also legal was copying music to an analog cassette tape, if the tape was not to be used for commercial purposes Third, music could be copied to special audio CD-Rs, mini-discs, and digital tapes if royalties had been paid on the media. Again, these copies could not be used for commercial purposes. Beyond that, the RIAA suggested there was no legal right to copy the copyrighted music on a CD onto a CD-R" and it was illegal to upload or download copyrighted music, give away CD copies, or lend original CDs to others for copying The organization's guidelines on piracy elaborated further Ilowever, burning a copy of a CD onto a CD-R, or transferring a copy to a computer hard drive or your portable music player, won't usually raise concerns so long as: The copy is made from an authorized original CD that you legitimately own The copy is just for your personal use." APPLE INC. In 2019, Apple was well known as the maker of the popular iPhone and as the world's first trillion-dollar company (a status it achieved in August 2018)," and it was also known for its Walled garden" ecosystem of softwarc, among other things. However, in 2001. Apple was best known as the maker of a niche computer that had largely ceded the desktop operating system war to Microsoft Windows. In 1997, when Dell Computer Corporation CEO Michael Dell was asked what he would do if he were put in charge of Apple, he answered, "Td shut it down and give the money back to the shareholders *** This was a firm that had come back from relative obscurity, launching a series of colourful iMac computers in the late 1990s to revive its brand In 2001, Apple had less than 3 per cent of the worldwide personal computer market share, trailing PC (97 per cent). Apple was faced with the challenge of trying to grow its loyal installed user base in a highly saturated and competitive market With 25 million users of its personal computer the Macintosh (Mac), worldwide, Apple had an iconic consumer brand, a loyal customer base, and a reputation for developing innovative products 4 Apple 14 Page 7 9B20M091 claimed to produce the entire computing package for a user, which in turn, allowed it to charge higher margins on its products. The Launch of iPods In 2001, Apple released the Apple iPod, a hard-drive-based music player with a retail price tag of $399, (Apple's gross margin was 64 per cent of the retail price.) Unlike the typical high-definition, full-colour, full-screen devices of 2019, the first iPod had a small black-and-white display in the top section of a white plastic body. Still, it was capable of storing approximately 1,024 digital songs"-a capacity almost 21 times greater than that of the leading MP3 player on the market. Along with the launch of iPod, Apple created an iPod Lounge website, where users could create user profiles make their own iPod accessories, such as iPod covers, and submit suggestions and ideas regarding iPod changes. The forum was moderated by Apple employees, who sifted through suggestions and forwarded the best ideas to the company Apple enlisted a few of the consumers who had been sued by the RIAA to star in television commercials supporting the launch of iPod The commercials featured dancing silhouettes wearing iPod's distinctive white headphones. Industry observers commented that the iPod was on its way to achieving iconic cult status, and many loyal Apple users considered the iPod to be as Windows users' first introduction to the "Apple way of life. The company also released Apple iPods by Hewlett-Packard and Dell with the only difference being a small company logo on the back of the Apple iPod below the Apple logo Apple widened consumer choice by continually launching variants on the iPod, such as the iPod mini (with a smaller-sized hard drive), the iPod nano (with a flash memory), and the iPod shuffle (an iPod without a screen or click wheel input) Each new generation of iPod typically featured additional refinements, a lower weight, and a smaller size. Notable changes included the touch-sensitive click wheel, which replaced a mechanical scroll wheel, the use of colour displays, and the addition of flash memory models. In addition, special limited-edition models were launched in collaboration with recording artists, athletes, and awareness campaigns to beighten consumer interest e Unit sales of the iPod grew steadily until 2010, and by 2011, they were exceeded by far by unit sales of the iPhone (see Exhibit 4) The Launch of iTunes Music Store Before the launch of the iTunes Music Store, Apple CEO Steve Jobs had to convince reluctant recording producers and artists to distribute their music online Jobs personally demonstrated the music service to key recording artists, emphasizing the clegance and simplicity of the iTunes Music Store and indicating that a credit card would be all that was required to purchase a song or album lle also emphasized his belief that consumers wanted to "own" the music they downloaded" The iTunes Music Store was launched in 2003, approximately two years after the iPod was first released The store began with 200,000 songs available to download, each at a cost of $0.99. Analysts were divided as to the profitability of iTune's digital downloads. While some believed Apple earned one cent per song in gross profit, others believed that the costs of running the iTunes Music Store could well exceed the $0.99 per song that Apple received Over the years, the iTunes Music Store grew in popularity. By February 2006, more than one billion songs had been downloaded from the store and in September 2006, iTunes became the first digital music store among the top five sellers of music in the United States (it was fifth overall). Its catalogue of downloads was broadened from music to include television shows, podcasts, video podcasts, and games. Page 8 9B20M091 Throughout his negotiations with the music executives, Jobs touted the inclusion of Apple's digital rights management software. Still, it took 18 months for Jobs and a small team of Apple employees to negotiate deals with the four major labels. As Hilary Rosen put it," it weren't for Steve Jobs' persistence, I don't think this would have happened. ***0 The Launch of iTunes Software and FairPlay, a Digital Rights Management System The new iTunes software was created concurrently with the launch of iPods in 2001 and bundled with cach Apple iPod purchased by users It was the only program that enabled users to play songs on their Apple iPods, and it used the company's proprietary FairPlay digital rights management (DRM) system. DRM systems allowed digital content vendors to control how material could be used on any electronic device on which they were installed. Apple's DRM system worked by encrypting (or "wrapping") each audio file to make it compatible with Apple iPods, and the system prevented songs from being traded on illegal P2P networks Standard digital formats such as MP3 could not be played on the iPod, a user had to rely on the iTunes software to convert MP3 files into Apple's chosen format, advanced audio coding (AAC), to play songs on the iPod In addition to encryption, iTunes also organized the songs on users' iPods into categories through features such as playlists and randomly auto-filled iPods from users' personal digital libraries Apple's DRM was not infallible. After the launch of the iTunes Music Store, several independent programmers were able to circumvent or remove the encryption from FairPlay-protected files. In 2005, Jon Johansen, a computer programmer, announced that he had developed a new program that stripped the DRM restriction from iTunes, allowing users to download and trade iTunes songs as if they were regular MP3 files. Within a week. Applc announced that it had modified iTunes software to plug the breach in security? In October 2006, Johansen announced that he had reverse-engineered Fair Play to allow Apple competitors to play their proprietary DRM-protected music and movies on iPods without having to work with Apple for permission. Authorized for use only in the tourse Sirate Management at Cape Breton University taught by De Peter Kerr from 1/17/2032 to 57/2029 Use outside these parameters is a copyright violation APPLE FACES COMPETITORS In the digital download market, new competitors were offering innovative pricing structures: Roxio, which had purchased the Napster name and assets, launched what would eventually become known as the music streaming industry in the fall of 2003, Roxio relaunched Napster as a legal online music downloading service, charging a monthly fee of $15.00 for unlimited access to songs. Instead of asking users to pay per song, Napster allowed consumers to fill portable digital music players with an unlimited amount of music for a monthly fee." In 2007, Napster allowed registered users to download every track in its two-million-song catalogue to their PCs and to listen to cach track up to three times at no charge. (Registration was free) To transfer an unlimited number of tracks to a compatible portable player (ie, not the iPod), registered users had to become subscribers, at a cost of $14.95 a month Subscribers could also purchase individual tracks at a cost of $0.99 each Roxio spent four years trying to grow the new Napster service in trying to convince users that paying a flat monthly fee was preferable to $0.99 a song, Roxio even ran an ad, during the 2005 Super Bowl, entitled Do the Math." The service was unsuccessful, and Napster was sold to Best Buy in the fall of 2008.95 Other online music download contenders included Motorola Inc., which announced plans for a mobile cellular phone that offered iTunes-type software: Yahoo! Music Unlimited: and Microsoft's MSN Music, Page 9 9B20M091 which operated from 2004 to 2006. Due to poor demand, Microsoft announced in November 2006 that it would shut down MSN Music and redirect visitors either to its Zune Marketplace website (Zune was also the brand name for Microsoft's new 30 GB portable music player, selling for $249.99) or to RealNetworks Rhapsody websites * Microsoft's Zune Marketplace website offered subscribers access to more than two million songs for $14.95 per month. Microsoft allowed a prospective subscriber to listen to songs for three days or three plays, whichever came first, after which the songs would expire unless the user purchased a subscription. A key differentiator between Zune and the other music players was the Wi-Fi connection that allowed users to share songs between Zune units wirelessly. APPLE LAUNCHES THE IPHONE Apple's executives initially refused to speculate about the iPod's prospects outside of digital music. The introduction of podcasting, however, apparently caused Apple to change its mind Podcasting-the term was derived from a combination of iPod and broadcasting-allowed users to download radio or television station broadcasts and listen to them at their leisure. By 2005, any podcaster (broadcast provider) was able to upload content to the iTunes Music Store In January 2007. Apple launched its iconic iPhone, and dropped the word computer from its new name. Apple Inc. While other mobile phones at the time had physical keyboards and pre-loaded software, the iPhone featured a touch-screen interface and allowed consumers to customize their devices with apps from Apple's App Store. The popularity of the iPhone allowed Apple's iTunes to become the largest music retailer in the world by 2010. By 2013, iTunes had 435 million users in 119 countries and had sold 25 billion songs 50 Sales of iPhones were 1.39 million units in 2007 and rose to a high of 231.22 million units in 2015 s' In comparison, sales of iPods went from 51.63 million in 2007 to 14.38 million in 2014. There was no official figure for iPod sales in 2015 because, in January of that year, Apple stopped reporting iPod unit sales Going forward, iPods would be lumped into the "Other Products" category." Authorized for use only in the course Strategic Management at Cape Breton University taught by Dr Peter Kerr from 1/17/2002 to 5/7/2022 Use outside these parameters is a copyright violation THE MUSIC STREAMING INDUSTRY The growing prominence of digital downloads in the music industry coincided with a rapid decline in the sale of physical music products. From $23.8 billion in 2001, global sales of music declined to $14.2 billion in 2014 The downward trend was reversed by the emergence of a new source of revenues streaming music, From about $400 million in 2010, streaming revenues rose to $1.9 billion by 2014 * Four years later, in 2018, the popularity of streaming boosted global music industry revenues to $19 1 billion, with streaming accounting for $8.9 billion of that total." Streaming was the latest business model disruption in the industry, and it led to a decline in the number of digital downloads. There were an estimated 60.4 million paying users for music streaming in 2019 alone In the US, revenue from streaming services more than doubled to $8.8 billion from 2016. In the US alone, 100 million listeners together streamed more than 500 billion songs 6 Alongside incumbents such as Apple, new competitors were entering the market. Apple Music Launched in June 2015, Apple Music charged prices between $4 99 per month and 14.99 per monthwith a three-month free introductory periodand gave customers access to a catalogue of 50 million songs. Page 10 9B20M091 While it did not offer a free, ad-supported version, Apple was able to convert 80 per cent of the people who tried the service into monthly active users and paid 73 per cent of its revenues, or $12.10 per 1,000 streams, to record labels. The service was available on all Apple devices and non-Apple personal computers and Android phones Apple Music, which differentiated its service by offering playlists curated by other users, reached 50 million paid subscribers in May 2018. Spotify The market leader in the streaming industry was Spotify, launched in 2008. It had a catalogue of more than 30 million songs, which included exclusive live recordings. A popular feature was its computer-generated playlists-Release Radar and Discover Weeklywhich were customized to user preferences and introduced users to new music Spotify had become the leader by offering a two-tiered service. The free, advertisement-supported version of its service was used by 54 per cent of Spotify listeners. The ad-free Spotify Premium service cost $4.99 to $14,99 a month. By the second quarter of 2019, Spotify had 180 global monthly active users, of which 83 million were paying subscribers Amazon Music, SoundCloud, YouTube Music In 2007, Amazon launched Amazon MP3, an online music store selling digital downloads While the company continued to make digital downloads available, it also launched Amazon Music Unlimited, a streaming service, in April 2017, this service cost $999 a month or $7.99 a month for Prime members SoundCloud, launched in 2008, aimed to connect music artists with fans. Its service cost $4.99 or $9.99 per month with the $9 99 service tier featuring 30 million tracks for listeners. Unlike other streaming services, SoundCloud featured an open platform, where artists could use software tools to market themselves directly to users. SoundCloud charged independent artists $70-$100 for these music creation tools. YouTube was the most popular online platform for audio entertainment. YouTube Music, launched in May 2018, offered a free, ad-supported version and a $9.99 per month YouTube Music Premium service that was similar to those of the market leaders. Authorized for use only in the course Strategic Management al Cape Broton University taughty De Pelet Kers from 1/17/2022 10 5/7/2002 Use outside these parameters is a copyright violation PREPARING FOR THE NEXT PHASE OF GROWTH: APPLE MEDIA? Apple Music was second only to Spotify in terms of the number of paying subscribers Apple Music had a market share of 20 per cent in 2018, suggesting that there was room to grow. Looking more broadly, analysts estimated that there was a total addressable market of $24 billion dollars in 2019. Further, Spotify with 35 per cent share was the market leader. Other top players include Amazon (11 per cent). Tencent Holdings Limited (10 per cent) and Youtube (5 per cent)." With Apple's new focus on generating revenue growth from services instead of hardware, it remained to be seen how the company's executives would position it for growth in the global music industry Apple's array of services included Apple Music, Apple Pay, the news subscription service Apple News+. 2 and the vidco subscription service Apple TV Plus. It was estimated that Apple Music and Media revenues would rise steadily from 2017 to 2025 (see Exhibit 5). Would the next step be to launch an Apple Media subscription service that bundled all of its media offers for one flat monthly fee? Page 11 9B20M091 EXHIBIT 1: GLOBAL RECORDED MUSIC REVENUES, 2001-2018 (in US$ billions] 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 233 21.7 200 19.4 04 18 1 10 14.2 2.7 - ONO OO 16.4 20 0.2 10 TONO FONN ANN Physical Digital (excluding streaming) Streaming Performance rights Synchronization revenues** Total 120 34 0.3 1.3 OWO o - ON 0.2 105 37 0.4 1.3 OG 0.1 0.6 0.7 0.8 90 39 0.4 1.4 03 151 1.0 1.0 1.2 239 22.4 208 20.8 202 19.6 18.4 171 16.0 (in US$ billions) 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 00 58 47 Physical Digital (excluding streaming) Streaming Performance rights Synchronization revenues Total 83 4.3 0.7 15 03 15 0 7.7 4.4 1.0 1.6 0.3 15.1 4.3 1.4 18 0.3 14.8 3.0 4.0 4.9 1.9 03 14.3 OOO mm 3.8 2.9 20 0.4 14.8 NONNOR 56 3.2 4.7 23 0.4 16.2 DM NO 52 2.6 6.7 2.4 0.4 17.4 2.3 8.9 2.7 04 19.1 "Totals were different due to rounding **Synchronization revenues a music synchronization license, also known as a sync license, was a music license granted by the owner or composer of a particular piece of work Source Created by the case authors using data from IFPI IFPI Global Music Report 2019-State of the Industry, IFPI. April 2, 2019, 13. accessed May 6, 2019, www.itpi.org/downloads/GMR2019.pdf. Authorized for use only in the course Strategic Management at Cape Breton University taught by Dr Polat Kerr from 1/17/2022 10 577/2002 Use outside these parameters is a copyright violation EXHIBIT 2: MUSIC RECORDING INDUSTRY CHART Song Writers Song Publishers Mechanical Rights Agency Recording Artist Recording Label Distributors Retailers Traditional and Online Consumer Hardware Manufacturers Distributors Source: Created by the case authors using data from various articles and industry executives. Page 12 9B20M091 EXHIBIT 3: VARIOUS ROYALTY AND REVENUE RATES FOR A TYPICAL CD RELEASE Party As % of Retail Price Songwriters 0.3% Song Publishers 0.3% Mechanical license (for music reproduction) 35% Recording artist-Gross Payments 16.5% Less packaging costs 4.1% Less promotional copies 1.2% Less return reserves 2 9% Less tours, videos, marketing Depends Less manager fees 3.3% Recording artist-Net Payments Depends Distributors 100% Retail 25 0% Record label Depends Notes Average CD Retail Price = $15.00 Recording artist net payments and record label gross profit varied depending on whether record sales could cover an estimated $600,000 in tours, video and marketing costs. Source: Created by the case authors using data from various articles and industry executives. EXHIBIT 4: IPOD AND IPHONE UNIT SALES, 2006-2018 250 Authorized for use only in the course Strategic Management al Cape Breton University taught by De Peter Kent from 1/17/2002 10 5/7/2022 Use outside these parameters is a convight violation 200 150 + Pod Unit Sses Phone Unit Sales 100 50 0 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2007 Unit Sales (Millions iPod Unit Sales Phone Unit Sales 2006 3941 3 51 63 139 2008 5483 11.63 2009 51.13 20.73 2010 50.31 39.99 2011 42.82 72.29 2012 2013 35 17 26.38 12505 150 255 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 14 38 169 22 23122 211.88 216 76 217.72 Notes. The iPhone was launched in 2007 and Apple stopped reporting iPod unit sales after 2014 Source: Created by the case authors using data from Shanhong Liu, "Unit Sales of the Apple iPhone Worldwide from 2007 to 2018 (in Millions). Statista, 2019, accessed May 6, 2019, www.statista.com/statistics/276306/global-apple-iphone-sales- since-fiscal-year-20071; Statista Research Department, "Global Apple iPod Sales from 2006 to 2014 (in Million Units) Statista, 2019, accessed May 6, 2019, www.statista.com/statistics/276307/global-apple-ipod-sales-since-fiscal-year-2006). Page 13 9B20M091 EXHIBIT 5: APPLE MUSIC AND MEDIA REVENUE FORECAST 1531 |||||| Sin Mins 2017 20 SE 2019E 2020E 20211 2022E 2023E 2004 2025 Installed Base of Apple Pay Devices 1,420 1,621 1.732 4,856 1,963 2,076 2192 2,321 WY Change 98 8% 6% 7% 75 6% 6% 6% 65 Apple Music Paid Subscriptors 35 54 79 106 136 173 207 238 262 YNY Change 75% 55% 45% 35% 30% 25 20% 15% 10% Installed Base 24 4% 5W 6% 981 10% 11% 115 Apple Music Revenue. Domestic N.mber Family Sutsertiore 4 G 9 12 15 19 23 26 2: Real Subscnpson Price $15 515 $45 $15 $15 515 $15 $15 $15 Family Subscrption Revenue 5893 31.073 $1,558 52 101 $2.732 $3415 84,097 $4.712 $5,183 Number of hd widual Subscntcns 14 21 31 41 54 67 81 53 102 Aerapa Subscrpion Price $10 $10 $0 510 $10 $10 $10 $10 $10 dvdual Subscription Revenue $1,636 52 536 $3,676 54.965 $6,454 SB 068 $9,682 $11,134 $12,247 Total Domesic Revende 52.329 53610 $5,234 57.066 99.186 $:14 513,779 $15.846 $17.430 Apple Music Revenue. Abroad Number al Family Sutsertion 4 6 9 12 15 190 23 26 28 Average Suspon Price $11 $11 $11 S11 $11 $11 $11 $11 511 Family Subscription Revenue 5520 S306 $1,168 51.577 52,160 V 563 51075 53.537 $3.699 N.mber of Indvidual Subscriptions 14 21 31 41 54 67 81 93 102 Average Subscnpson Price $7 $7 $7 57 $7 57 $7 $7 Indvdual Subsorption Hevenue $1,104 51 710 $2.480 53 348 $4,353 55 441 $6,529 57.508 $8,259 Total Acai kelente $1,623 52 516 $3,648 54.925 56,403 58 004 89,504 $11.045 512,150 Total Apple Music Revenue $1,952 $6.126 $8,813 $11.992 $15,589 $19.486 $23,994 $26,891 $29,590 YY Change 119 56% 45% 30% 5 || 15% TON Number of Media Subscrptore 4 12 17 26 36 48 Hverage Subtopion Price incrementato M.BC) 55 $6 $5 55 $5 55 $5 SS 55 Meda Subscription Revenue SO $0 50 5319 $621 S1036 $1.553 52.143 52.751 Apple Music Media Revenue $3,952 56.126 $8,B! 3 512310 516,210 $20 522 524,937 $29.034 $32.331 Change 113 55% 45% 32% 32 27% 22% 16% 118 Source: Created by the case authors using data from Samik Chatterjee, Apple," J.P. Morgan September 27, 2018, 100 . le JEG Tg 2014 RI thorized for use only in the course Strategic Management al Capo Proton University taught by Di Polerken from 1/17/2022 10 5/7/2092 THIS Iht winiati se ideas Page 14 9B20M091 ENDNOTES This case has been written on the basis of published sources only. Consequeritly, the interpretation and perspectives presented in this case are not necessarily those of Apple Inc. or any of its employees. Tim Bradshaw "Apple to Stop Revealing Unit Sales Sparking Peak iPhone Fears,' Financial Times. November 1, 2018, accessed May 6 2019, www.ft.com/content/Sefo264c-de 3d-11e8-9f04-38d397e6661c. Amy Watson. Share of Music Streaming Subscribers Worldwide as of the First Half of 2018, By Company" 2019, accessed May 6, 2019, www.statista.com/statistics/653926/music-streaming-service-subscriber-sharel * Rachel Rosmarin, "Pod Killers That Didn't 2006. accessed Feb 27, 2020, www.forbes.com/2006/10/20/ipod-zune-rio-tech- media-cx_rr_1023killers.html#490b246d1a91 Eliot Van Buskirk, Zune Eats Creative's Meager Lunch. Grabbing 4 Percent of MP3 Player Market," 2008, accessed February 27, 2020 www.wired.com/2008/05/ipod-loses-mark All dollar amounts in US dollars unless specified otherwise. ? "FPI Global Music Report 2019 State of the Industry." IFPI. April 2, 2019, accessed May 6 2019, www.itpi.org/downloads/GMR2019.pdf Ibid. U.S. Recorded Music Revenues Accesses Feb 27, 2020 www.riaa.com/u-s-sales-database/. " Michael Mertens, Thieves in Cyberspace: Examining Music Piracy And Copyright Law Deficiencies in Russia As It Enters The Digital Age, 14, University of Miami International and Comparative Law Review, 139 (2006), accessed February 27, 2020, https://repository law.miami edu/umicir/vol14/iss 1/4. Mike Wiser. "Why Do CDs Cost So Much?.- in "The Way the Music Died," PBS Frontline, May 27, 2004, accessed June 15, 2005. www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/music/inside/faqs.htmi. 12 In 2011 UMG: 29.85%. SME 29.29%, WMG 19.13%, EMI 9.62%, in total these four have 87.89%. The Nielsen Company & Billboard's 2011 Music Industry Report Businesswire, 2012 accessed February 27 2020, www.businesswire.comews/home/20120105005547/en/Nielsen-Company-Billboard%E2%80%995-2011-Music-industry-Repart. 11 Geoffrey Hull, Thomas Hutchison, and Richard Strasser, 2011. The Music and Recording Business. Routledge. (p 281) 14 Sudip Bhattacharjee, Ram D. Gopal, Kaveepan Lertwachara and James R. Marsden impact of Legal Threats on Online Music Sharing Activity: An Analysis of Music Industry Legal Actions. The Journal of Law & Economics Vol. 49 No. 1 (April 2006) 15 "RIAA sues MP3.com, alleges copyright violations", CNET, January 2002, accessed February 28, 2020, www.cnet.comews/riaa-sues-mp3-com-alleges-copyright violations/ * Maria Seminerio, Stop the music! Diamond Multimedia faces lawsuit over its Rio player,' October 1998, accessed Feb 28 2020 www.zdnet.com/article/stop-the-music-diamond-multimedia-faces-lawsuit-over-its-ric-player! 17 Sam Costello. "Digital Music Security Initiative Nearly Ready CNN. September, 2000. accessed March 2, 2020, www.cnn.com/2000/TECH/computing/09/22/SDM.prep.idg/index.htmi. 14 Sue Zeidler "Hackers Insist They Beat Audio Technology CIOL. October 2000. accessed March 2, 2020, www.ciol.com/hackers-insist-beat-audio-technology 19 Steven Levy. "The Man Can't Stop Our Music Newsweek, March 27, 2000, accessed July 25, 2019, www.newsweek.com/man-cant-stop-our-music-156803. 20 Edward Hellmore, "Music Industry Is Caught Napping, Guardian, March 16, 2000, accessed July 25, 2019, www.theguardian.com/technclogy/2000/mar/16/onlinesupplement4. 21 "Napster Has Plan, The Economist February 2001. accessed February 28 2020 www.economist.com/unknown/2001/02/21apster-has-a-plan. 22 Vickie L. Feeman, William S Coats, Heather D. Rafter, and John G. Given. "Revenge of the Record Industry Association of America: The Rise and Fall of Napster," VIN, Sports & Ent. LJ 9 (2002) 35 (p 36, footnote 9). 23 Sam Costello "Anti-Napster Ruling Draws Mixed Reaction, PCWorld, February 12, 2001, accessed July 25, 2019, www.pcworld.ig.com.au/article/20087/anti-napster_ruling_draws_mixed reaction/ 24 Helimare, op. cit. [Edward Helmore, "Music Industry is Caught Napping," Guardian, March 16, 2000 accessed July 25, 2019. www.theguardian.com/technology/2000/mar/16/anlinesupplement4.1 * Matt Richtel, The Napster Decision: The Overview, Apellate Judges Back Limitations on Copying Music. New York Time, February 13, 2001, accessed February 29, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2001/02/13/businessapster-decision-overview- appellate-judges-back-limitations-copying-music.html: Peter Cohen 'Roxio to Acquire Napster Assets." MawWorld, November 15, 2002 accessed February 29, 2020, https://www.macworld.com/article/1007839/roxio html 28 Justice Dep't Begins Probe into MusicNet, Pressplay.' Billboard. August 2001, accessed February 29, 2020. www.billboard.com/articlesews/78850/justice-dept-begins-probe-into-musicnet-pressplay, 27 "12-year-old Settles Music Swap Lawsuit CNN, February 2004, accessed February 29, 2020 www.cnn.com/2003/TECHAnternet/09/09/music swap settlement 2 Wiser, op. cit. [Mike Wiser 'Why Do CDs Cost So Much?," in "The way the Music Died, PBS Frontline, May 27, 2004, accessed June 15, 2005. www.pbs.org/ugbh/pages/frontine/shows/music/inside/faqs.html] Amy Schatz et al. "High Court to Old Media: You Win, Wall Street Journal, June 28, 2005, B1. S "About Piracy. RIAA accessed July 26, 2019, www.siaa.com/resources-learning/about-piracy! s' Tim Bradshaw, Apple Wins Race to be First Trillion Dollar Company" Financial Times August 2, 2018, accessed May 6. 2019. www.ft.com/content/aebad290-9644-11e8-b670-b8205561c3le Authorized for use only in the course Strategic Management at Cape Breton University taught by Dr Peter Kerr from 1/17/2022 to 5/7/2022 Use outside these parameters is a copyright violation a

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts