Question: A junior level manager was overheard to say: This difference between managers and leaders is just silliness. It is just an artificiality created by scholars

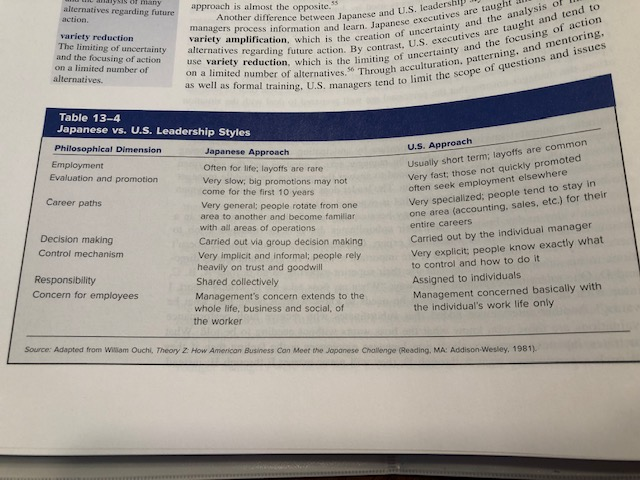

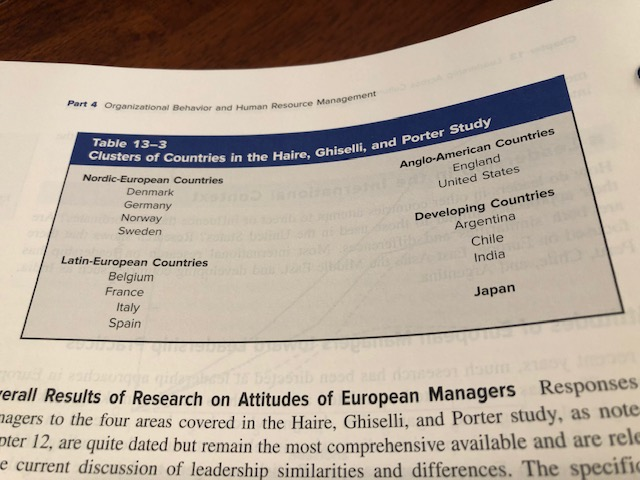

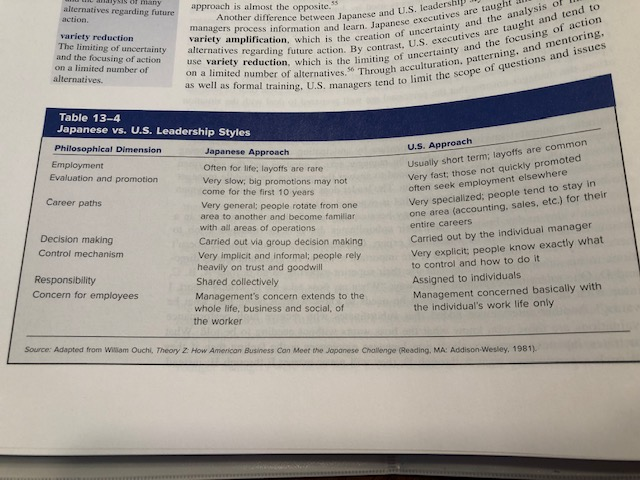

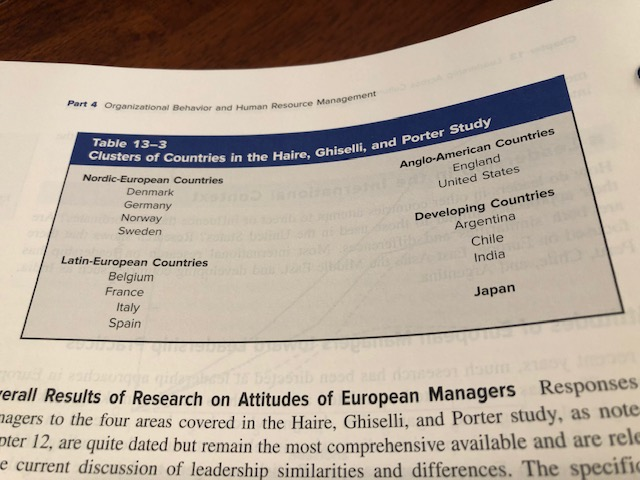

A junior level manager was overheard to say: "This difference between managers and leaders is just silliness. It is just an artificiality created by scholars so that they have something to argue about." Question #2: Defend or refute that assertion. Figures 13-3 and 13-4 provide some unique insight from long ago. Before you assail the credibility of the study, I should mention that Administrative Science Quarterly (ASQ) is considered by most scholars to be THE journal. Take a moment to carefully scrutinize that material. Can we agree that a leaders' time is a valuable and scarce resource? Perhaps the most non-fungible resource available? (If you want to debate that, I'd point you towards Henry Mintzberg's book: The Nature of Managerial Work for starters.) Let us call this concept "Point #1" for the moment. One study of 845 American workers revealed that 70% of the respondents agreed with the statement that: "workers should work as hard as they could when they are at work." It hopefully is no surprise that, when asked if they actually do that, only 23% replied in the affirmative. A different study revealed that 25% of respondents admitted they would be perfectly happy if they could just stay home, perform no work, and still receive their paychecks. Now, thankfully you wonderful, hard-working, eager-to-learn students are NOT like that. I mean, you all are serious scholars who want to master the complicated and intricate details of International Management. Right? You would have been heartbroken if, back in January, I had said: This is bogus. It is mind-numbing repetition of all the junk you learned in International Business (which about half of you admitted you had already taken). So, let's just have one quiz over chapter one and give everybody an "A" for their efforts. That way we can concentrate on more important things in other classes and life." You would have been so devastated, that I'm sure you would have run right to the Dean and demanded that he force me to work you like a rented mule so that you get your money's worth out of your tuition. I'm right, aren't I? Or, would the "average" student have pocketed the "A" and gone away smiling? (Don't answer those questions in print.) Not wanting to work any harder than they have to in order to graduate? (Please don't debate with me on this-I've seen too many students, too many semesters. I know they are out there. Not you, of course.) Let us call this concept Point #2" for the moment. Can we agree that the "average" student (not you, of course) would be more likely to turn up in Figure 13-4 with the Low-Achievement Motivation" group? Let us call this concept "Point #3" for the moment. If you have granted me Points #1, #2, and #3, then... Is it not logical for me to adopt Leadership style 1,1low task, low people? Up through Session 5, the productivity is superior to two other Leadership styles, and not all that much below the Leadership style 9,1-high task, low people. By Session 7 the productivity results are hardly distinguishable between the 9,9 (workaholic) professor and the 1,1 (lazy) professor. And it saves me all the lecturing, yelling, screaming, quizzing, threatening, grading, testing, coercing, and leading required to be "high task, high people for the semester. Question #3: Defend or refute that assertion. SiS o many alternatives regarding future action. d the a approach is almost the opposite. Another difference between lananese and U.S. leaders managers process information and learn Japanese execute Variety amplification, which is the creation of uncer alternatives regarding future action. By contr use variety reduction, which is the limiting on a limited number of alternatives. Through as well as formal training. U.S. managers tend to limit variety reduction The limiting of uncertainty and the focusing of action on a limited number of alternatives ast. U.S. execy and the te. and med issues se executives are taught in uncertainty and the analysis of in > contrast, US executives are taught and tend to ng of uncertainty and the focusing of action Through acculturation patterning and mentoring. to limit the scope of questions and issues Table 13-4 Japanese vs. U.S. Leadership Styles Philosophical Dimension Japanese Approach Employment Often for life; layoffs are rare Evaluation and promotion Very slow, big promotions may not come for the first 10 years Career paths Very general people rotate from one area to another and become familiar with all areas of operations Decision making Carried out via group decision making Control mechanism Very implicit and informal: people rely heavily on trust and goodwill Responsibility Shared collectively Concern for employees Management's concern extends to the whole life, business and social, of the worker U.S. Approach Usually short term; layoffs are common Very fast; those not quickly promoted often seek employment elsewhere Very specialized: people tend to stay in one area (accounting, sales, etc.) for their entire careers Carried out by the individual manager Very explicit: people know exactly what to control and how to do it Assigned to individuals Management concerned basically with the individual's work life only Source: Adapted from William Ouchi, Theory How American Business Con Meet the Japanese Challenge (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1981) Organizational Behavior and Human Resource Manage ce Management Table 13-3 Clusters of Countries in the Haire, Ghisell Nordic-European Countries Denmark Germany Norway Sweden re, Ghiselli, and Porter Study Anglo-American Countries England United States Developing countries Argentina Chile India Latin-European Countries Belgium France Italy Spain Japan orch on Attitudes of European Managers Responses gers to the four areas covered in the Haire. Ghiselli, and Porter study, as note Dler 12, are quite dated but remain the most comprehensive available and are relo e current discussion of leadership similarities and differences. The specie