Question: Analysis What is the Real Problem tin the case that is be below. a. Common Causes - Compare the causes and look for commonality b.

Analysis What is the Real Problem tin the case that is be below.

a. Common Causes - Compare the causes and look for commonality

b. Primary Problem - Based on commonality identify THE primary problem

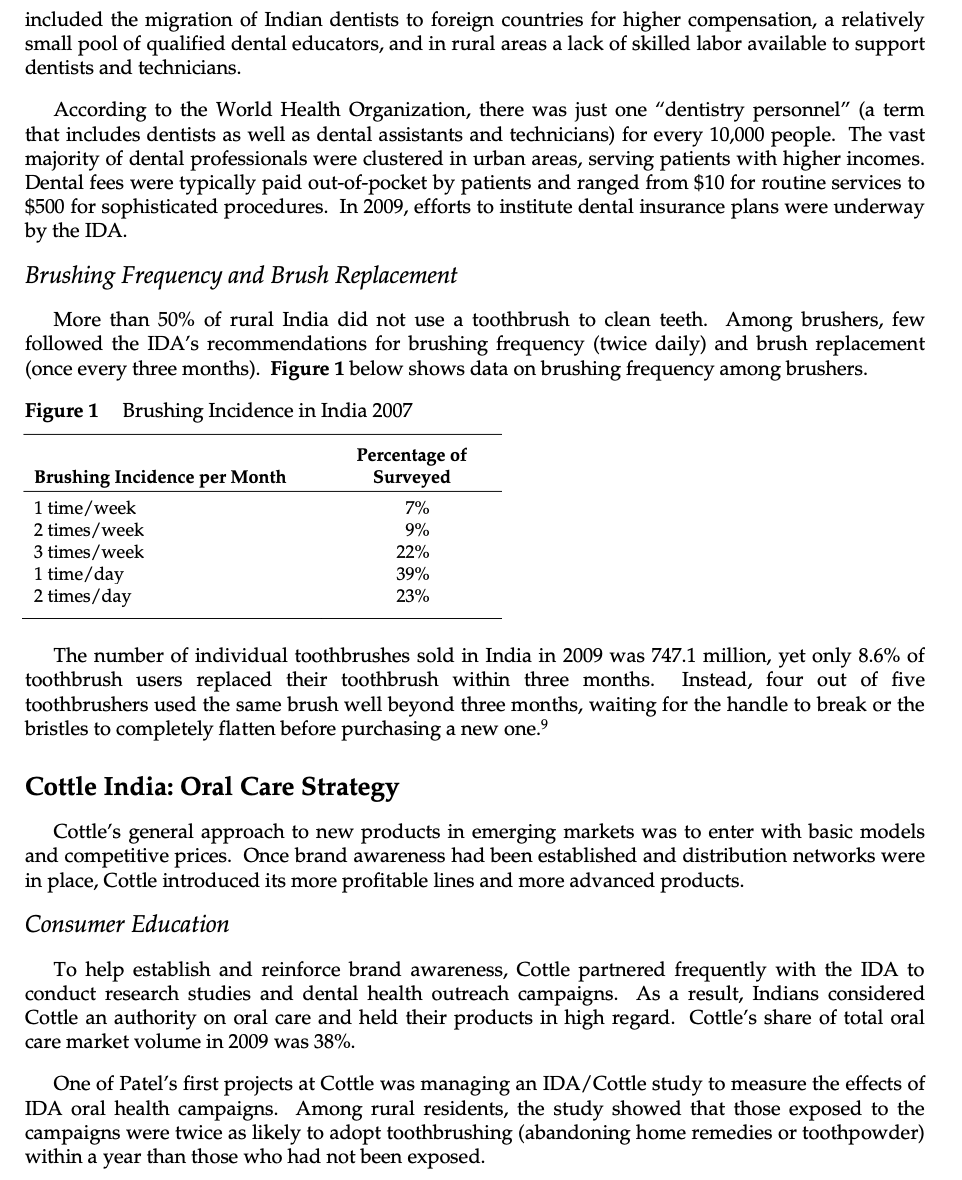

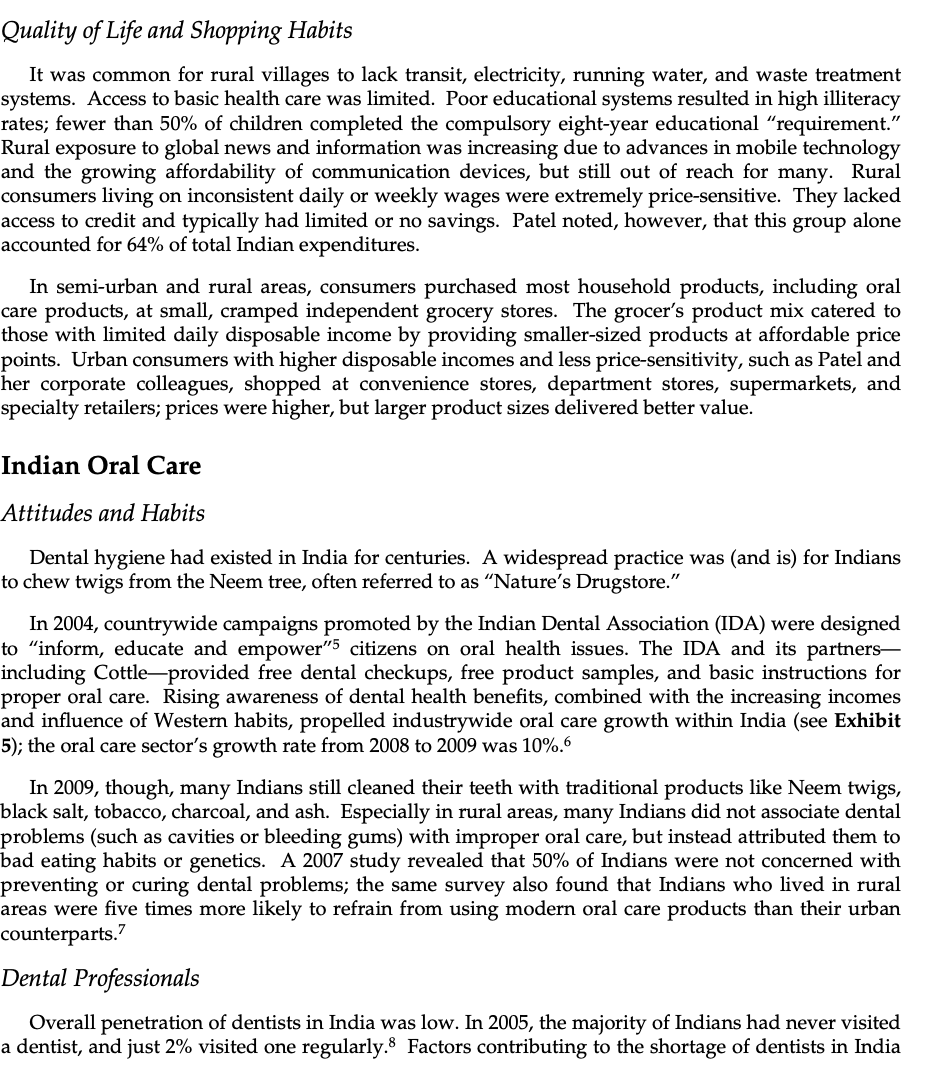

Brinda Patel, director of oral-care marketing for the India division of Cottle-Taylor (Cottle), re- examined the toothbrush marketing plan she'd just presented to her manager, Michael Lang. It was October 2009, and for the last two months Patel had developed data-driven 2010 marketing plans for each of the oral care markets. Based on input from sales and marketing colleagues, Patel was confident that her toothbrush plan would support a 20% increase in toothbrush unit salesup 2% from the 2009 plan's growth projectionfueled primarily by rising demand for modern oral-care products in India. However, Lang found Patel's 2010 sales forecast conservative. It was Lang's responsibility as VP of Marketing for Greater Asia and Africa to approve marketing plans for each of the 14 regions he managed. Cottle's senior management, faced with declining U.S. revenues, had looked to emerging markets to offset domestic losses, and Lang was under pressure to deliver results. He needed a higher unit sales and revenue contribution from India to boost his region's bottom line. Brinda," he said, "you and I read the same study that confirmed roughly half of all Indians are still not concerned with preventing or curing dental problems. I want you to see this as an opportunity to engage 500 million customers. Our strategy hinges on securing early market share in emerging markets, and the competition in India is likely to heat up quickly. We have to achieve faster growth in 2010 than you are projecting." With a 2009 population of more than one billion, India represented an enormous revenue opportunity for Cottle. Lang believed that by increasing toothbrush-related advertising and promotional spending beyond 12% of salesthe 2009 levelCottle could accelerate market development in India, as it had in Thailand in 2007. Lang strongly believed a toothbrush unit growth rate of 25%-30% in India was achievable in 2010. Patel questioned Lang's assumption that India would duplicate Thailand's numbers. Given the breadth of his assignment, Lang spent little time in India. Did he understand that, despite its recent economic growth, more than three-quarters of Indians lived on less than two dollars a day? Patel felt her plan, which assumed no negative effects on volume despite upcoming price increases, was aggressive but achievable. She worried, too, about increasing adspend during the recession, when Cottle was cost-conscious. Would she have to reduce her department's headcount to afford Lang's proposed advertising plan? The Company Philadelphia-based Cottle was founded in 1815 as a hand-soap manufacturer. By 2009, the company produced more than 200 products to serve three consumer-product categories: oral care, personal care (soaps, lotions, deodorants, etc.), and home care (laundry and dishwashing products led this group). Its 2009 revenues were $11.5 billion. Cottle's products were sold in more than 200 countries worldwide. Cottle-Taylor Global Organization and Financial Performance Cottle viewed geographic expansion and new-product development as key drivers of growth in foreign markets and divided its global operations into four geographic divisions: North America, Europe, Latin America, and Greater Asia and Africa. (See Exhibit 1 for a breakdown of Cottle's 2009 revenue by region.) By 2009 roughly 50% of the company's revenues, or $5.7 billion, came from emerging markets. To serve this customer base, Cottle maintained manufacturing and business operations in 75 countries. The company believed in providing quality products around the globe; unlike some competitors, Cottle employed a predominantly international workforce and invested heavily in foreign communities. "Hiring local talent is critical to maximizing international sales and driving country-specific innovation," claimed Mark Hernandez, Cottle's CEO. Excited by Cottle's commitment to international employees, Brinda Patel joined Cottle India in 2008. "Before Cottle, I worked in marketing at the Mumbai office of a large multinational. Our office's relationship with U.S. headquarters was disjointed, and they weren't flexible enough to capitalize on developing opportunities here in India. Morale was low," Patel explained. "Here at Cottle, our U.S. headquarters relies on my team for strategic advice and research on the Indian market, and I count on my U.S. colleagues for marketing and sales support. It's truly a collaborative environment." In 2009, the dominant sales strategy at Cottle world headquarters emphasized increasing global sales of higher-margin products along with geographic expansion. Yet, many consumers in developing countries did not perceive a need for the more profitable, sophisticated products the company pushed from its US office. In India, Patel's research had indicated only a small subset of wealthy consumers could afford a battery-operated toothbrush. With limited discretionary spending, the majority of Indians wanted to upgrade from home-grown dental remedies to inexpensive modern oral care products. Between 2004 and 2009, Cottle's sales grew by 8% annually, net income by 12%, and earnings per share by 14%. While personal and home care generated strong sales in the United States and Europe, oral care anchored the company's success in emerging markets. (See Exhibit 2 for Cottle's 2009 Global Oral Care revenues, and Exhibit 3 for details on Cottle's 2009 Greater Asia/Africa Oral Care revenues.) India Operations Indian business operations were conducted through a subsidiary-Cottle Indiaand focused exclusively on oral care; Cottle India manufactured toothpaste, toothpowder (a powder-based cleanser typically used without a toothbrush), and toothbrushes. As the market for modern oral care products developed, Cottle planned to introduce ancillary products, including mouthwash and dental floss. Within India, Cottle's distribution network was wide; its products were sold in more than 450,000 retail outlets throughout the country, from small bodegas in one-shop towns to closet-sized urban sidewalk vendors to supermarkets and specialty retailers. India in 2009 Demographics and Economic Growth India was the world's largest democracy. Its 1.2 million square miles of varied topography hosted a 2009 population of 1.16 billion, with a median age of 25 and an annual growth rate of 1.4%. Population control campaigns had succeeded in slowing growth rates to 17% for the first decade of the 21st century. The country was divided into 28 states and 9 territories; Hindi was the primary language and English the second, although the number of officially recognized languages (excluding English) was 22. Changes in economic policy introduced in 1991 helped to shift the country away from the highly regulated and protectionist economic environment that was established when India gained independence from Britain in 1947. During the 1990s, foreign investors and businesses, optimistic about growth prospects, poured money into India. The GDP rapidly expanded as a result; in 2009 GDP was 146 times greater than in 1990. Yet the distribution of newfound economic prosperity was inconsistent across India. In 2009, just three of the 37 states and territoriesMaharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, and Andra Pradesh (where Patel had grown up)accounted for 30% of India's total GDP.2 Despite economic growth, India struggled to free vast swaths of its population from poverty. Roughly 37% (or 429 million individuals) lived below the poverty line, defined by the World Bank as $1.25 U.S. per day. Some estimates suggested that as much as 80% lived on less than $2 per day. (See Exhibit 4 for snapshots of household disposable income in 2005 and 2009.) In 2009, roughly 78% of Indians (905 million) lived in rural towns and villages and 22% (255 million) in urban settings. However, farmers seeking higher wages as manual laborers were rapidly migrating to cities. While new wealth fueled improvements in urban areas, abject poverty remained there as well. Propelled by the continual influx of rural residents to cities, the number of Indians living in slums (defined as dwellings with no solid roof and no on-site access to a toilet or clean drinking water) was projected to reach 8% of the population (93 million) by 2011.4 Quality of Life and Shopping Habits It was common for rural villages to lack transit, electricity, running water, and waste treatment systems. Access to basic health care was limited. Poor educational systems resulted in high illiteracy rates; fewer than 50% of children completed the compulsory eight-year educational "requirement." Rural exposure to global news and information was increasing due to advances in mobile technology and the growing affordability of communication devices, but still out of reach for many. Rural consumers living on inconsistent daily or weekly wages were extremely price-sensitive. They lacked access to credit and typically had limited or no savings. Patel noted, however, that this group alone accounted for 64% of total Indian expenditures. In semi-urban and rural areas, consumers purchased most household products, including oral care products, at small, cramped independent grocery stores. The grocer's product mix catered to those with limited daily disposable income by providing smaller-sized products at affordable price points. Urban consumers with higher disposable incomes and less price-sensitivity, such as Patel and her corporate colleagues, shopped at convenience stores, department stores, supermarkets, and specialty retailers; prices were higher, but larger product sizes delivered better value. Indian Oral Care Attitudes and Habits Dental hygiene had existed in India for centuries. A widespread practice was (and is) for Indians to chew twigs from the Neem tree, often referred to as Nature's Drugstore." In 2004, countrywide campaigns promoted by the Indian Dental Association (IDA) were designed to "inform, educate and empower"5 citizens on oral health issues. The IDA and its partners including Cottle-provided free dental checkups, free product samples, and basic instructions for proper oral care. Rising awareness of dental health benefits, combined with the increasing incomes and influence of Western habits, propelled industrywide oral care growth within India (see Exhibit 5); the oral care sector's growth rate from 2008 to 2009 was 10%. In 2009, though, many Indians still cleaned their teeth with traditional products like Neem twigs, black salt, tobacco, charcoal, and ash. Especially in rural areas, many Indians did not associate dental problems (such as cavities or bleeding gums) with improper oral care, but instead attributed them to bad eating habits or genetics. A 2007 study revealed that 50% of Indians were not concerned with preventing or curing dental problems; the same survey also found that Indians who lived in rural areas were five times more likely to refrain from using modern oral care products than their urban counterparts.? Dental Professionals Overall penetration of dentists in India was low. In 2005, the majority of Indians had never visited a dentist, and just 2% visited one regularly. Factors contributing to the shortage of dentists in India included the migration of Indian dentists to foreign countries for higher compensation, a relatively small pool of qualified dental educators, and in rural areas a lack of skilled labor available to support dentists and technicians. According to the World Health Organization, there was just one "dentistry personnel (a term that includes dentists as well as dental assistants and technicians) for every 10,000 people. The vast majority of dental professionals were clustered in urban areas, serving patients with higher incomes. Dental fees were typically paid out-of-pocket by patients and ranged from $10 for routine services to $500 for sophisticated procedures. In 2009, efforts to institute dental insurance plans were underway by the IDA. Brushing Frequency and Brush Replacement More than 50% of rural India did not use a toothbrush to clean teeth. Among brushers, few followed the IDA's recommendations for brushing frequency (twice daily) and brush replacement (once every three months). Figure 1 below shows data on brushing frequency among brushers. Figure 1 Brushing Incidence in India 2007 Brushing Incidence per Month 1 time/week 2 times/week 3 times/week 1 time/day 2 times/day Percentage of Surveyed 7% 9% 22% 39% 23% The number of individual toothbrushes sold in India in 2009 was 747.1 million, yet only 8.6% of toothbrush users replaced their toothbrush within three months. Instead, four out of five toothbrushers used the same brush well beyond three months, waiting for the handle to break or the bristles to completely flatten before purchasing a new one. Cottle India: Oral Care Strategy Cottle's general approach to new products in emerging markets was to enter with basic models and competitive prices. Once brand awareness had been established and distribution networks were in place, Cottle introduced its more profitable lines and more advanced products. Consumer Education To help establish and reinforce brand awareness, Cottle partnered frequently with the IDA to conduct research studies and dental health outreach campaigns. As a result, Indians considered Cottle an authority on oral care and held their products in high regard. Cottle's share of total oral care market volume in 2009 was 38%. One of Patel's first projects at Cottle was managing an IDA/Cottle study to measure the effects of IDA oral health campaigns. Among rural residents, the study showed that those exposed to the campaigns were twice as likely to adopt toothbrushing (abandoning home remedies or toothpowder) within a year than those who had not been exposed. Product Manufacturing Toothpaste and Toothpowder Ingredients for toothpaste and toothpowder were inexpensive and locally available, and blending equipment was not cost-prohibitive. As a result, entrepreneurs from India and China had entered the Indian market with low-priced and specialty offerings (such as herbal and ayurvedic paste) in recent years. To remain competitive, Cottle lowered its prices on basic toothpastes and toothpowder. Since 2004, Cottle's gross margin on basic toothpaste and toothpowder prices had dropped from 31% to 25% as a result of decreases in price. Toothbrushes In contrast to pastes and powders, toothbrush production required financial and manufacturing resources such as specialized equipment for molding plastic handles and trimming bristles. Having operated in India for more than 50 years, Cottle had invested in growing its toothbrush manufacturing capacity and improving productivity over time. By 2009 the company could adjust its product mix to meet demand without relying on the expensive and sometimes risky import process. In 2009, Cottle India's toothbrush sales accounted for 17.5% of total Cottle India oral care sales, with toothpaste and toothpowder contributing 48.7% and 33.8% respectively (see Exhibit 6). Patel and Lang had agreed to leverage Cottle's competitive advantage in toothbrushes as profit margins from toothpaste and toothpowder declined. By focusing on the toothbrush market, Cottle aimed to secure early market share in low- and mid-range products. Long-range forecasts called for a gradual shift to higher-end brushes. Toothbrush Product Line Cottle's U.S. headquarters believed in making its full line of oral care products available to all of its global subsidiaries. Management found it helpful to provide its country managers with results from successful new product launches in markets around the world. Furnished with compelling sales data and strategic guidance from headquarters, country managers from emerging markets were more willing to introduce new products to consumers. Each of Cottle's manual toothbrush designs came in a variety of colors; all styles included rubber grips. Low-End Manual The Complete: Basic manual toothbrush with soft, multi-height bristles designed to reach crevices within and between teeth. The Sensitooth: Soft bristles and a minimally flexible neck to minimize gum aggravation. The FreshGum: A soft and curve-bristled toothbrush to massage gums with textured tongue cleaner on reverse of head. The Surround: Specially designed to clean teeth, tongue, cheeks and gums with multi-height and multi-functional bristles, as well as a ridged, textured tongue cleaner on reverse of head. The Kidsie: Extra soft bristles, small head, and cartoon character handles. Mid-Range Manual The Zagger: Multi-angled bristles and tongue cleaner. Directionflex: Most flexible head (bendable 45 degrees in every direction) with tongue cleaner on reverse of head Battery-Operated The Swirl: Battery-operated, rotating bristles that perform 3,000 strokes/minute. Swirl Refills: Easy-to-replace head refills for The Swirl battery-operated brush. delayed payments. Rural retailers in particular found inventory planning difficult, as sales were highly correlated with daily and weekly incomes of their customers. Wages of day laborers fluctuated highly due to changing factors such as job availability and weather. Dentists and Distribution With the growing awareness of the importance of good dental hygiene, Cottle plotted how to leverage the dentist distribution channel. In early 2009, U.S. management had conducted a study to quantify the benefits of its battery-operated toothbrush. The study demonstrated that battery brushes were more effective than manual brushes in removing plaque and nearly 20% better at reducing gum bleeding-a prevalent problem in Indian dental patients. Patel was working with the IDA to communicate these results to Indian dentistskey influencers of the small but lucrative group of potential battery-operated customers. Partnering with dentists had been an effective way to get new products into the hands of consumers in Thailand, and Patel believed Indian dentists would be especially effective as future distributors for its battery-operated toothbrush system. Communications As indicated in Exhibit 9, Cottle India's oral care division spent 9% of gross toothbrush sales in 2009 on toothbrush-related advertising and 3% on promotions and merchandising; 10% was for off- invoice allowances for trade deals. Media advertising primarily targeted men and women aged 2035 in both rural and urban locations. Approximately 50% of the ad budget was spent on television, 30% on print ads in newspapers, 15% on billboards and outdoor displays, and 5% on radio. Campaigns were weighted to mid-range products to encourage consumers to trade up. U.S. headquarters produced television advertisements for global use, expecting country managers to add local flavor by inserting native voiceovers and local product shots. Cottle India managers differed, however, on the relative importance of the three key messages that factored into brushing: (1) persuading consumers to brush for the first time, (2) increasing the incidence of brushing, and (3) persuading consumers to upgrade to mid-range or premium products. Patel's predecessor had determined that each theme was critical to Cottle India's growth, and as a compromise, the marketing budget in 2008 and 2009 had been split in three to satisfy these messages equally. Patel's 2010 plan followed this strategy, but after reviewing her draft Lang advised her that he did not favor an even distribution of dollars in 2010though he said no more than that. Patel's instinct was to allocate more advertising dollars to messages (1) and (2), to attract new rural brushers and increase the overall incidence of brushing. Patel expected, though, that Lang's plan would want to give more weight to message (3) to generate higher unit sales of mid-range and high-end products, due to the success of a similar campaign in Thailand. Cottle Thailand: Effects of Increased Advertising in 2006 In 2006, Lang had worked with Cottle's Thailand oral care manager to accelerate the growth of toothbrush market, which had been averaging a 17% unit growth rate. Having studied Thailand's steadily rising income levels and increasing exposure to western influences, Lang believed Thai incomes and tastes would support higher unit sales for mid-range and battery-operated toothbrushes. A lack of awareness and understanding of these products' benefits, he felt, was contributing to consumer inertia. Lang felt that in 2009, India's cultural and economic trends would, like Thailand in 2006, support a larger share of mid-range and high-end unit sales. Take a look at unit and sales growth from 2006 to 2007 in Thailand," Lang had advised Patel. There, we increased advertising by 3% of sales, and shifted product mix and messaging towards mid-range and high-end audiences. Our 2007 unit sales increased by 25%-nearly 6% higher than the 19% growth we had been projecting before we allocated additional ad dollars." (See Exhibit 10 for Thailand's 20052007 unit sales.) "My projections aim to increase unit sales of low-end brushes by 16%, of mid-range brushes by 120%, and battery-operated by 25%." Planning for 2010 Lang had confided in Patel that Cottle's senior management had decided to tie a greater proportion of 2010 employee compensation to regional performance in 2010; their plan was to reward regions that met or exceeded sales objectives and to reorganize those that underperformed. Patel understood the pressure Lang was under. Lang had given her two days to produce a revised toothbrush marketing plan that came closer to his goal of 30% unit sales growth. She was determined to meet his objectives for 2010. Lang had made it clear that he wanted to explore increasing advertising budget above 12% of sales, along with eliminating the even distribution of ad dollars across the three key messages. "When we get together in two days, I'd like to see an outline of each message's target audience, and your thoughts on the message's short-term and long-term benefits," he told Patel. He also asked for recommendation on how to distribute advertising dollars, stating the assumptions underlying her recommendations. Patel reflected on the disparity between her urban contemporaries and those living in the remote villages she had seen on a recent trek. What messages would resonate most with them, she wondered? How many rural consumers had the desire to adopt a modern approach to oral care? And how quickly would those with growing disposable incomes perceive a need for more sophisticated products? Patel reviewed her initial projections for Cottle's toothbrush line in India. She was curious to quantify the effect of product mix changes; what would 2009 revenue and profitability have looked like with Thailand's product mix? She opened her laptop to build a projected income statement based on her 2010 plan, and also one for the scenario Lang had suggested. Would a 3% increase in ad dollars necessarily lead to higher revenues and profitability? Brinda Patel, director of oral-care marketing for the India division of Cottle-Taylor (Cottle), re- examined the toothbrush marketing plan she'd just presented to her manager, Michael Lang. It was October 2009, and for the last two months Patel had developed data-driven 2010 marketing plans for each of the oral care markets. Based on input from sales and marketing colleagues, Patel was confident that her toothbrush plan would support a 20% increase in toothbrush unit salesup 2% from the 2009 plan's growth projectionfueled primarily by rising demand for modern oral-care products in India. However, Lang found Patel's 2010 sales forecast conservative. It was Lang's responsibility as VP of Marketing for Greater Asia and Africa to approve marketing plans for each of the 14 regions he managed. Cottle's senior management, faced with declining U.S. revenues, had looked to emerging markets to offset domestic losses, and Lang was under pressure to deliver results. He needed a higher unit sales and revenue contribution from India to boost his region's bottom line. Brinda," he said, "you and I read the same study that confirmed roughly half of all Indians are still not concerned with preventing or curing dental problems. I want you to see this as an opportunity to engage 500 million customers. Our strategy hinges on securing early market share in emerging markets, and the competition in India is likely to heat up quickly. We have to achieve faster growth in 2010 than you are projecting." With a 2009 population of more than one billion, India represented an enormous revenue opportunity for Cottle. Lang believed that by increasing toothbrush-related advertising and promotional spending beyond 12% of salesthe 2009 levelCottle could accelerate market development in India, as it had in Thailand in 2007. Lang strongly believed a toothbrush unit growth rate of 25%-30% in India was achievable in 2010. Patel questioned Lang's assumption that India would duplicate Thailand's numbers. Given the breadth of his assignment, Lang spent little time in India. Did he understand that, despite its recent economic growth, more than three-quarters of Indians lived on less than two dollars a day? Patel felt her plan, which assumed no negative effects on volume despite upcoming price increases, was aggressive but achievable. She worried, too, about increasing adspend during the recession, when Cottle was cost-conscious. Would she have to reduce her department's headcount to afford Lang's proposed advertising plan? The Company Philadelphia-based Cottle was founded in 1815 as a hand-soap manufacturer. By 2009, the company produced more than 200 products to serve three consumer-product categories: oral care, personal care (soaps, lotions, deodorants, etc.), and home care (laundry and dishwashing products led this group). Its 2009 revenues were $11.5 billion. Cottle's products were sold in more than 200 countries worldwide. Cottle-Taylor Global Organization and Financial Performance Cottle viewed geographic expansion and new-product development as key drivers of growth in foreign markets and divided its global operations into four geographic divisions: North America, Europe, Latin America, and Greater Asia and Africa. (See Exhibit 1 for a breakdown of Cottle's 2009 revenue by region.) By 2009 roughly 50% of the company's revenues, or $5.7 billion, came from emerging markets. To serve this customer base, Cottle maintained manufacturing and business operations in 75 countries. The company believed in providing quality products around the globe; unlike some competitors, Cottle employed a predominantly international workforce and invested heavily in foreign communities. "Hiring local talent is critical to maximizing international sales and driving country-specific innovation," claimed Mark Hernandez, Cottle's CEO. Excited by Cottle's commitment to international employees, Brinda Patel joined Cottle India in 2008. "Before Cottle, I worked in marketing at the Mumbai office of a large multinational. Our office's relationship with U.S. headquarters was disjointed, and they weren't flexible enough to capitalize on developing opportunities here in India. Morale was low," Patel explained. "Here at Cottle, our U.S. headquarters relies on my team for strategic advice and research on the Indian market, and I count on my U.S. colleagues for marketing and sales support. It's truly a collaborative environment." In 2009, the dominant sales strategy at Cottle world headquarters emphasized increasing global sales of higher-margin products along with geographic expansion. Yet, many consumers in developing countries did not perceive a need for the more profitable, sophisticated products the company pushed from its US office. In India, Patel's research had indicated only a small subset of wealthy consumers could afford a battery-operated toothbrush. With limited discretionary spending, the majority of Indians wanted to upgrade from home-grown dental remedies to inexpensive modern oral care products. Between 2004 and 2009, Cottle's sales grew by 8% annually, net income by 12%, and earnings per share by 14%. While personal and home care generated strong sales in the United States and Europe, oral care anchored the company's success in emerging markets. (See Exhibit 2 for Cottle's 2009 Global Oral Care revenues, and Exhibit 3 for details on Cottle's 2009 Greater Asia/Africa Oral Care revenues.) India Operations Indian business operations were conducted through a subsidiary-Cottle Indiaand focused exclusively on oral care; Cottle India manufactured toothpaste, toothpowder (a powder-based cleanser typically used without a toothbrush), and toothbrushes. As the market for modern oral care products developed, Cottle planned to introduce ancillary products, including mouthwash and dental floss. Within India, Cottle's distribution network was wide; its products were sold in more than 450,000 retail outlets throughout the country, from small bodegas in one-shop towns to closet-sized urban sidewalk vendors to supermarkets and specialty retailers. India in 2009 Demographics and Economic Growth India was the world's largest democracy. Its 1.2 million square miles of varied topography hosted a 2009 population of 1.16 billion, with a median age of 25 and an annual growth rate of 1.4%. Population control campaigns had succeeded in slowing growth rates to 17% for the first decade of the 21st century. The country was divided into 28 states and 9 territories; Hindi was the primary language and English the second, although the number of officially recognized languages (excluding English) was 22. Changes in economic policy introduced in 1991 helped to shift the country away from the highly regulated and protectionist economic environment that was established when India gained independence from Britain in 1947. During the 1990s, foreign investors and businesses, optimistic about growth prospects, poured money into India. The GDP rapidly expanded as a result; in 2009 GDP was 146 times greater than in 1990. Yet the distribution of newfound economic prosperity was inconsistent across India. In 2009, just three of the 37 states and territoriesMaharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, and Andra Pradesh (where Patel had grown up)accounted for 30% of India's total GDP.2 Despite economic growth, India struggled to free vast swaths of its population from poverty. Roughly 37% (or 429 million individuals) lived below the poverty line, defined by the World Bank as $1.25 U.S. per day. Some estimates suggested that as much as 80% lived on less than $2 per day. (See Exhibit 4 for snapshots of household disposable income in 2005 and 2009.) In 2009, roughly 78% of Indians (905 million) lived in rural towns and villages and 22% (255 million) in urban settings. However, farmers seeking higher wages as manual laborers were rapidly migrating to cities. While new wealth fueled improvements in urban areas, abject poverty remained there as well. Propelled by the continual influx of rural residents to cities, the number of Indians living in slums (defined as dwellings with no solid roof and no on-site access to a toilet or clean drinking water) was projected to reach 8% of the population (93 million) by 2011.4 Quality of Life and Shopping Habits It was common for rural villages to lack transit, electricity, running water, and waste treatment systems. Access to basic health care was limited. Poor educational systems resulted in high illiteracy rates; fewer than 50% of children completed the compulsory eight-year educational "requirement." Rural exposure to global news and information was increasing due to advances in mobile technology and the growing affordability of communication devices, but still out of reach for many. Rural consumers living on inconsistent daily or weekly wages were extremely price-sensitive. They lacked access to credit and typically had limited or no savings. Patel noted, however, that this group alone accounted for 64% of total Indian expenditures. In semi-urban and rural areas, consumers purchased most household products, including oral care products, at small, cramped independent grocery stores. The grocer's product mix catered to those with limited daily disposable income by providing smaller-sized products at affordable price points. Urban consumers with higher disposable incomes and less price-sensitivity, such as Patel and her corporate colleagues, shopped at convenience stores, department stores, supermarkets, and specialty retailers; prices were higher, but larger product sizes delivered better value. Indian Oral Care Attitudes and Habits Dental hygiene had existed in India for centuries. A widespread practice was (and is) for Indians to chew twigs from the Neem tree, often referred to as Nature's Drugstore." In 2004, countrywide campaigns promoted by the Indian Dental Association (IDA) were designed to "inform, educate and empower"5 citizens on oral health issues. The IDA and its partners including Cottle-provided free dental checkups, free product samples, and basic instructions for proper oral care. Rising awareness of dental health benefits, combined with the increasing incomes and influence of Western habits, propelled industrywide oral care growth within India (see Exhibit 5); the oral care sector's growth rate from 2008 to 2009 was 10%. In 2009, though, many Indians still cleaned their teeth with traditional products like Neem twigs, black salt, tobacco, charcoal, and ash. Especially in rural areas, many Indians did not associate dental problems (such as cavities or bleeding gums) with improper oral care, but instead attributed them to bad eating habits or genetics. A 2007 study revealed that 50% of Indians were not concerned with preventing or curing dental problems; the same survey also found that Indians who lived in rural areas were five times more likely to refrain from using modern oral care products than their urban counterparts.? Dental Professionals Overall penetration of dentists in India was low. In 2005, the majority of Indians had never visited a dentist, and just 2% visited one regularly. Factors contributing to the shortage of dentists in India included the migration of Indian dentists to foreign countries for higher compensation, a relatively small pool of qualified dental educators, and in rural areas a lack of skilled labor available to support dentists and technicians. According to the World Health Organization, there was just one "dentistry personnel (a term that includes dentists as well as dental assistants and technicians) for every 10,000 people. The vast majority of dental professionals were clustered in urban areas, serving patients with higher incomes. Dental fees were typically paid out-of-pocket by patients and ranged from $10 for routine services to $500 for sophisticated procedures. In 2009, efforts to institute dental insurance plans were underway by the IDA. Brushing Frequency and Brush Replacement More than 50% of rural India did not use a toothbrush to clean teeth. Among brushers, few followed the IDA's recommendations for brushing frequency (twice daily) and brush replacement (once every three months). Figure 1 below shows data on brushing frequency among brushers. Figure 1 Brushing Incidence in India 2007 Brushing Incidence per Month 1 time/week 2 times/week 3 times/week 1 time/day 2 times/day Percentage of Surveyed 7% 9% 22% 39% 23% The number of individual toothbrushes sold in India in 2009 was 747.1 million, yet only 8.6% of toothbrush users replaced their toothbrush within three months. Instead, four out of five toothbrushers used the same brush well beyond three months, waiting for the handle to break or the bristles to completely flatten before purchasing a new one. Cottle India: Oral Care Strategy Cottle's general approach to new products in emerging markets was to enter with basic models and competitive prices. Once brand awareness had been established and distribution networks were in place, Cottle introduced its more profitable lines and more advanced products. Consumer Education To help establish and reinforce brand awareness, Cottle partnered frequently with the IDA to conduct research studies and dental health outreach campaigns. As a result, Indians considered Cottle an authority on oral care and held their products in high regard. Cottle's share of total oral care market volume in 2009 was 38%. One of Patel's first projects at Cottle was managing an IDA/Cottle study to measure the effects of IDA oral health campaigns. Among rural residents, the study showed that those exposed to the campaigns were twice as likely to adopt toothbrushing (abandoning home remedies or toothpowder) within a year than those who had not been exposed. Product Manufacturing Toothpaste and Toothpowder Ingredients for toothpaste and toothpowder were inexpensive and locally available, and blending equipment was not cost-prohibitive. As a result, entrepreneurs from India and China had entered the Indian market with low-priced and specialty offerings (such as herbal and ayurvedic paste) in recent years. To remain competitive, Cottle lowered its prices on basic toothpastes and toothpowder. Since 2004, Cottle's gross margin on basic toothpaste and toothpowder prices had dropped from 31% to 25% as a result of decreases in price. Toothbrushes In contrast to pastes and powders, toothbrush production required financial and manufacturing resources such as specialized equipment for molding plastic handles and trimming bristles. Having operated in India for more than 50 years, Cottle had invested in growing its toothbrush manufacturing capacity and improving productivity over time. By 2009 the company could adjust its product mix to meet demand without relying on the expensive and sometimes risky import process. In 2009, Cottle India's toothbrush sales accounted for 17.5% of total Cottle India oral care sales, with toothpaste and toothpowder contributing 48.7% and 33.8% respectively (see Exhibit 6). Patel and Lang had agreed to leverage Cottle's competitive advantage in toothbrushes as profit margins from toothpaste and toothpowder declined. By focusing on the toothbrush market, Cottle aimed to secure early market share in low- and mid-range products. Long-range forecasts called for a gradual shift to higher-end brushes. Toothbrush Product Line Cottle's U.S. headquarters believed in making its full line of oral care products available to all of its global subsidiaries. Management found it helpful to provide its country managers with results from successful new product launches in markets around the world. Furnished with compelling sales data and strategic guidance from headquarters, country managers from emerging markets were more willing to introduce new products to consumers. Each of Cottle's manual toothbrush designs came in a variety of colors; all styles included rubber grips. Low-End Manual The Complete: Basic manual toothbrush with soft, multi-height bristles designed to reach crevices within and between teeth. The Sensitooth: Soft bristles and a minimally flexible neck to minimize gum aggravation. The FreshGum: A soft and curve-bristled toothbrush to massage gums with textured tongue cleaner on reverse of head. The Surround: Specially designed to clean teeth, tongue, cheeks and gums with multi-height and multi-functional bristles, as well as a ridged, textured tongue cleaner on reverse of head. The Kidsie: Extra soft bristles, small head, and cartoon character handles. Mid-Range Manual The Zagger: Multi-angled bristles and tongue cleaner. Directionflex: Most flexible head (bendable 45 degrees in every direction) with tongue cleaner on reverse of head Battery-Operated The Swirl: Battery-operated, rotating bristles that perform 3,000 strokes/minute. Swirl Refills: Easy-to-replace head refills for The Swirl battery-operated brush. delayed payments. Rural retailers in particular found inventory planning difficult, as sales were highly correlated with daily and weekly incomes of their customers. Wages of day laborers fluctuated highly due to changing factors such as job availability and weather. Dentists and Distribution With the growing awareness of the importance of good dental hygiene, Cottle plotted how to leverage the dentist distribution channel. In early 2009, U.S. management had conducted a study to quantify the benefits of its battery-operated toothbrush. The study demonstrated that battery brushes were more effective than manual brushes in removing plaque and nearly 20% better at reducing gum bleeding-a prevalent problem in Indian dental patients. Patel was working with the IDA to communicate these results to Indian dentistskey influencers of the small but lucrative group of potential battery-operated customers. Partnering with dentists had been an effective way to get new products into the hands of consumers in Thailand, and Patel believed Indian dentists would be especially effective as future distributors for its battery-operated toothbrush system. Communications As indicated in Exhibit 9, Cottle India's oral care division spent 9% of gross toothbrush sales in 2009 on toothbrush-related advertising and 3% on promotions and merchandising; 10% was for off- invoice allowances for trade deals. Media advertising primarily targeted men and women aged 2035 in both rural and urban locations. Approximately 50% of the ad budget was spent on television, 30% on print ads in newspapers, 15% on billboards and outdoor displays, and 5% on radio. Campaigns were weighted to mid-range products to encourage consumers to trade up. U.S. headquarters produced television advertisements for global use, expecting country managers to add local flavor by inserting native voiceovers and local product shots. Cottle India managers differed, however, on the relative importance of the three key messages that factored into brushing: (1) persuading consumers to brush for the first time, (2) increasing the incidence of brushing, and (3) persuading consumers to upgrade to mid-range or premium products. Patel's predecessor had determined that each theme was critical to Cottle India's growth, and as a compromise, the marketing budget in 2008 and 2009 had been split in three to satisfy these messages equally. Patel's 2010 plan followed this strategy, but after reviewing her draft Lang advised her that he did not favor an even distribution of dollars in 2010though he said no more than that. Patel's instinct was to allocate more advertising dollars to messages (1) and (2), to attract new rural brushers and increase the overall incidence of brushing. Patel expected, though, that Lang's plan would want to give more weight to message (3) to generate higher unit sales of mid-range and high-end products, due to the success of a similar campaign in Thailand. Cottle Thailand: Effects of Increased Advertising in 2006 In 2006, Lang had worked with Cottle's Thailand oral care manager to accelerate the growth of toothbrush market, which had been averaging a 17% unit growth rate. Having studied Thailand's steadily rising income levels and increasing exposure to western influences, Lang believed Thai incomes and tastes would support higher unit sales for mid-range and battery-operated toothbrushes. A lack of awareness and understanding of these products' benefits, he felt, was contributing to consumer inertia. Lang felt that in 2009, India's cultural and economic trends would, like Thailand in 2006, support a larger share of mid-range and high-end unit sales. Take a look at unit and sales growth from 2006 to 2007 in Thailand," Lang had advised Patel. There, we increased advertising by 3% of sales, and shifted product mix and messaging towards mid-range and high-end audiences. Our 2007 unit sales increased by 25%-nearly 6% higher than the 19% growth we had been projecting before we allocated additional ad dollars." (See Exhibit 10 for Thailand's 20052007 unit sales.) "My projections aim to increase unit sales of low-end brushes by 16%, of mid-range brushes by 120%, and battery-operated by 25%." Planning for 2010 Lang had confided in Patel that Cottle's senior management had decided to tie a greater proportion of 2010 employee compensation to regional performance in 2010; their plan was to reward regions that met or exceeded sales objectives and to reorganize those that underperformed. Patel understood the pressure Lang was under. Lang had given her two days to produce a revised toothbrush marketing plan that came closer to his goal of 30% unit sales growth. She was determined to meet his objectives for 2010. Lang had made it clear that he wanted to explore increasing advertising budget above 12% of sales, along with eliminating the even distribution of ad dollars across the three key messages. "When we get together in two days, I'd like to see an outline of each message's target audience, and your thoughts on the message's short-term and long-term benefits," he told Patel. He also asked for recommendation on how to distribute advertising dollars, stating the assumptions underlying her recommendations. Patel reflected on the disparity between her urban contemporaries and those living in the remote villages she had seen on a recent trek. What messages would resonate most with them, she wondered? How many rural consumers had the desire to adopt a modern approach to oral care? And how quickly would those with growing disposable incomes perceive a need for more sophisticated products? Patel reviewed her initial projections for Cottle's toothbrush line in India. She was curious to quantify the effect of product mix changes; what would 2009 revenue and profitability have looked like with Thailand's product mix? She opened her laptop to build a projected income statement based on her 2010 plan, and also one for the scenario Lang had suggested. Would a 3% increase in ad dollars necessarily lead to higher revenues and profitability