Question: Base on the above information, please answer the following question. (If possible, please also tell me which part did you get the answer/ideas from) 1.

Base on the above information, please answer the following question. (If possible, please also tell me which part did you get the answer/ideas from)

Base on the above information, please answer the following question. (If possible, please also tell me which part did you get the answer/ideas from)

1. What are some advantages of using the decision-making procedures discussed in chapter 7? What are some disadvantages? Explain.

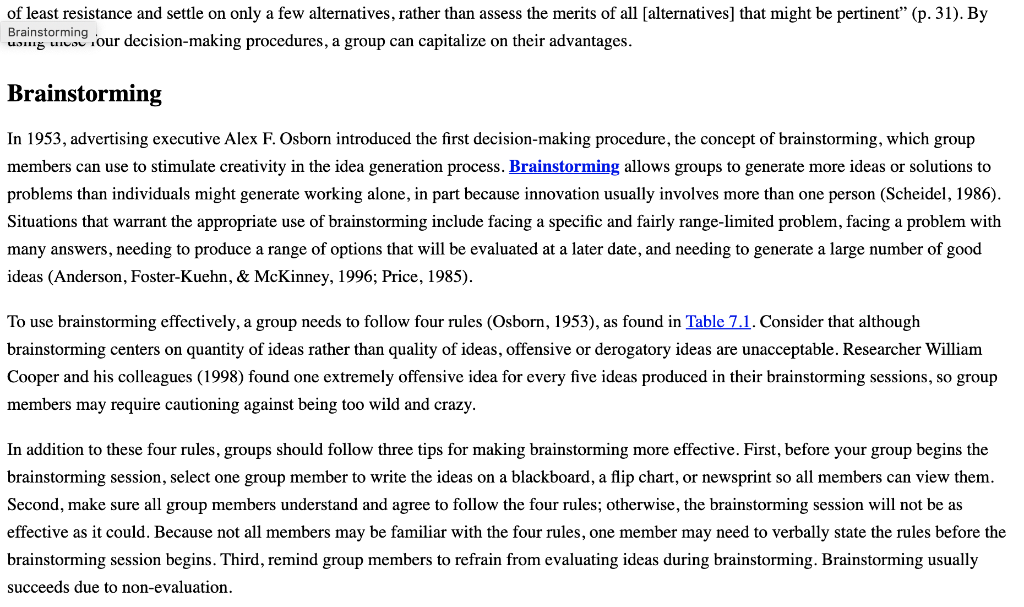

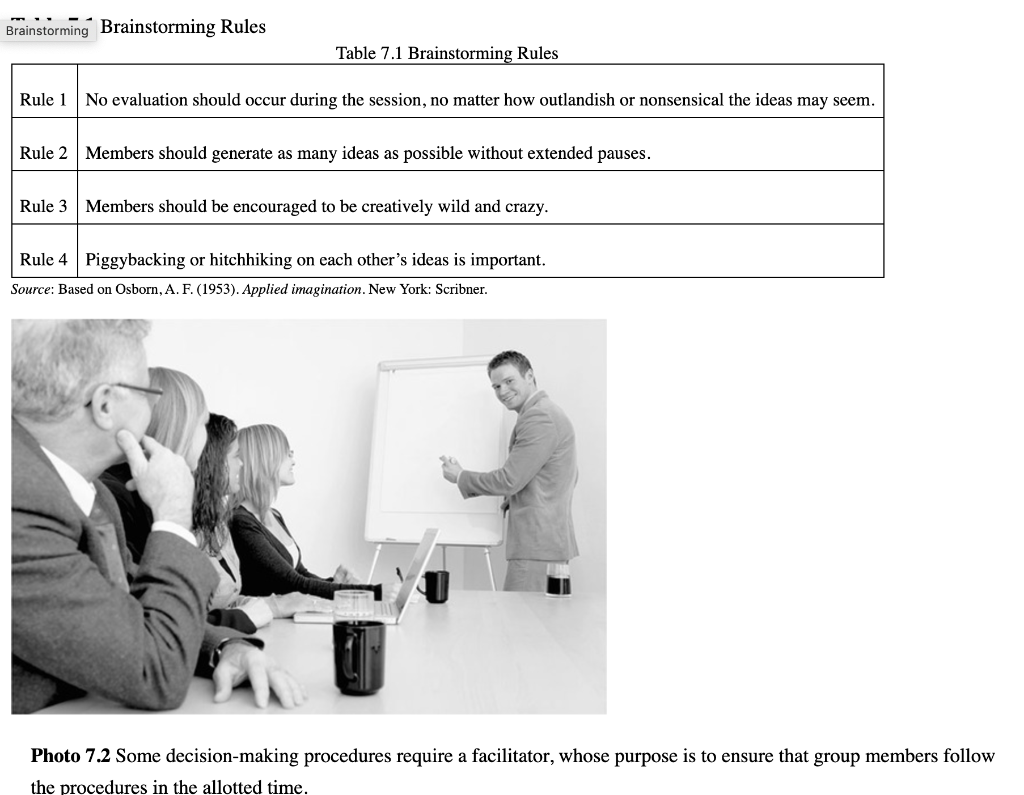

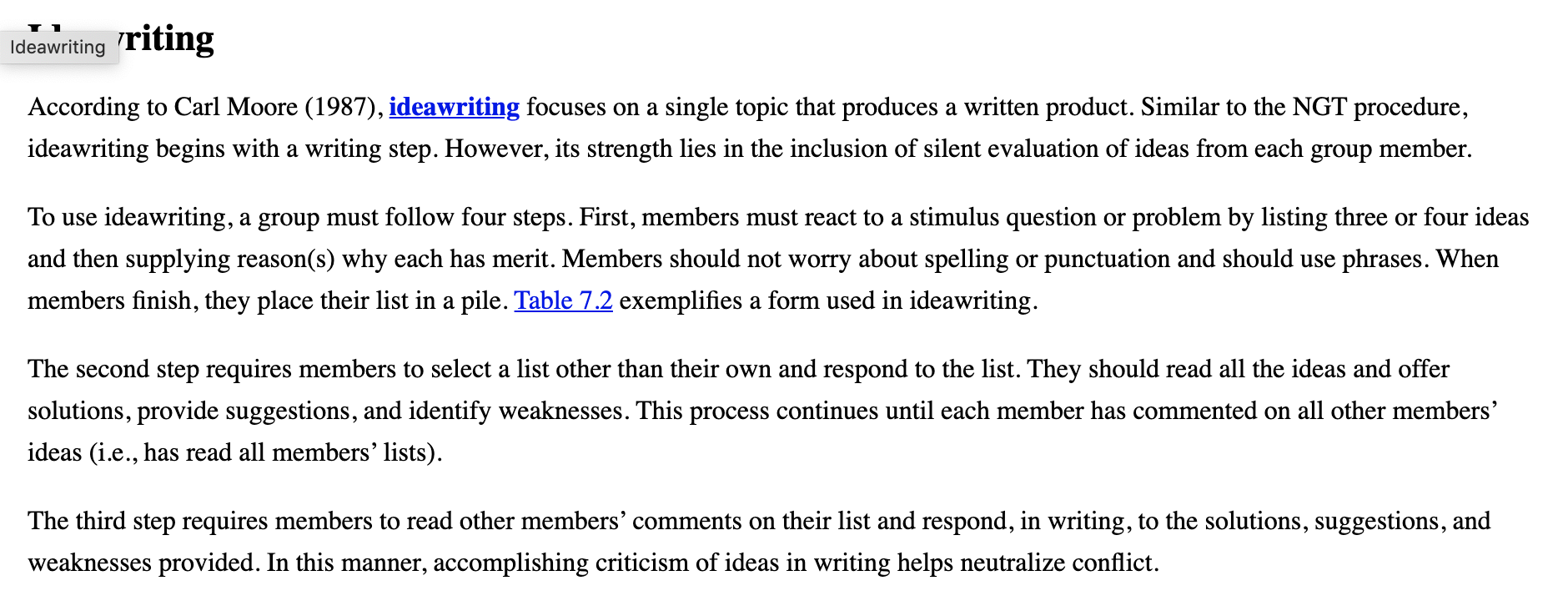

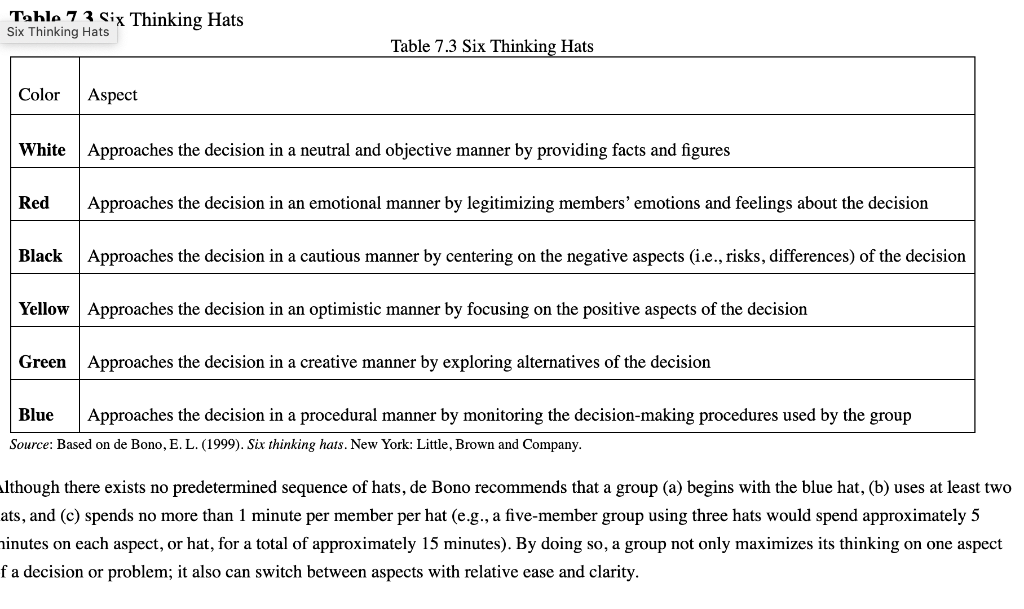

Definition of Decision-Making Procedures According to group communication scholars David Seibold and Dean Krikorian (1997), decision-making procedures describe structured methods of decision making that coordinate group members' communication, keep members focused on the issues at hand, and guide members through the process of problem diagnosis, solution selection, or solution implementation. Each decision-making procedure occurs within a controlled situation, in which one or two members facilitate the group's process. Because decision-making procedures impose structure on the group's discussion of an issue, groups can avoid haphazard or poor decision making or premature decisions that result in poor group performance. Furthermore, small group communication expert Randy Hirokawa (1980) found that members of effective groups use more procedural statements and spend more time discussing procedural matters than members of ineffective groups. To evaluate the quality of a group's decisions, examine the type of decision-making procedures it uses (Pavitt & Curtis, 1994). ? What are some decision-making procedures currently used by your work group? How effective are these procedures? Types of Decision-Making Procedures Although groups can choose among several types of decision-making procedures (Jarboe, 1999; Jones, 1998; Sunwolf, 2002; Sunwolf & Seibold, 1999), any group, including your classroom group, can use the following four procedures: brainstorming, nominal group technique, ideawriting, and six thinking hats. Although the steps of each procedure vary, group scholars Michele Jackson and Marshall Scott Poole (2003) noted that most idea generation procedures share four common principles. First, these procedures encourage generation of many ideas. Second, the members focus on one single activity, the generation of ideas as a group. Third, groups that want to produce must make members follow a set of rules or steps in working through the decision-making process. Fourth, as a group activity, the members must commit to using the procedures in a cooperative group climate. As group experts Dennis Gouran and Randy Hirokawa (2003) noted, human nature causes group members to "follow the lines of least resistance and settle on only a few alternatives, rather than assess the merits of all alternatives) that might be pertinent (p. 31). By using uring our decision-making procedures, a group can capitalize on their advantages. Brainstorming In 1953, advertising executive Alex F. Osborn introduced the first decision-making procedure, the concept of brainstorming, which group members can use to stimulate creativity in the idea generation process. Brainstorming allows groups to generate more ideas or solutions to problems than individuals might generate working alone, in part because innovation usually involves more than one person (Scheidel, 1986). Situations that warrant the appropriate use of brainstorming include facing a specific and fairly range-limited problem, facing a problem with many answers, needing to produce a range of options that will be evaluated at a later date, and needing to generate a large number of good ideas (Anderson, Foster-Kuehn, & McKinney, 1996; Price, 1985). To use brainstorming effectively, a group needs to follow four rules (Osborn, 1953), as found in Table 7.1. Consider that although brainstorming centers on quantity of ideas rather than quality of ideas, offensive or derogatory ideas are unacceptable. Researcher William Cooper and his colleagues (1998) found one extremely offensive idea for every five ideas produced in their brainstorming sessions, so group members may require cautioning against being too wild and crazy. In addition to these four rules, groups should follow three tips for making brainstorming more effective. First, before your group begins the brainstorming session, select one group member to write the ideas on a blackboard, a flip chart, or newsprint so all members can view them. Second, make sure all group members understand and agree to follow the four rules; otherwise, the brainstorming session will not be as effective as it could. Because not all members may be familiar with the four rules, one member may need to verbally state the rules before the brainstorming session begins. Third, remind group members to refrain from evaluating ideas during brainstorming. Brainstorming usually succeeds due to non-evaluation. Brainstorming Brainstorming Rules Table 7.1 Brainstorming Rules Rule 1 No evaluation should occur during the session, no matter how outlandish or nonsensical the ideas may seem. Rule 2 Members should generate as many ideas as possible without extended pauses. Rule 3 Members should be encouraged to be creatively wild and crazy. Rule 4 Piggybacking or hitchhiking on each other's ideas is important. Source: Based on Osborn, A. F. (1953). Applied imagination. New York: Scribner. Photo 7.2 Some decision-making procedures require a facilitator, whose purpose is to ensure that group members follow the procedures in the allotted time. If we make cure our group members think creatively when generating ideas, you will realize the ease required to conduct a brainstorming Nominal Group Technique session and the fun involved in unleashing creativity, although a brainstorming session should last no longer than 30 minutes (Gautschi, 1990a). Groups may want to use this procedure along with other decision-making procedures, such as the nominal group technique decision- making procedure. Nominal Group Technique The second decision-making procedure, a popular one, is nominal group technique or NGT (Delbecq, Van de Ven, & Gustafson, 1975). Nominal group technique allows members to independently and silently generate ideas, but not as a group. NGT permits members to work alone, combine ideas afterward, and later view the process as one in which they worked as a group (Green, 1975). Although NGT compares to brainstorming in that it first requires members to engage in idea generation, the independence of idea generation and the silent recording of each member's ideas present NGT as a more democratic process. This procedure minimizes persuasive influences by group members, especially the influence of powerful and high-status members (Seibold & Krikorian, 1997). As such, NGT is an appropriate procedure to use when some group members dominate group discussion or when status differences in the group inhibit equal participation (Anderson et al., 1996). An ideal decision-making procedure for use with 5 to 9 participants, NGT is guided by a facilitator, or an individual who purports to ensure that group members follow the decision-making procedure in the time allotted. Some behaviors used by the facilitator include engaging in active communication skills (e.g., listening, maintaining eye contact, paraphrasing members' statements), maintaining the group momentum, remaining neutral during the group discussion, and treating the information disclosed in the group as confidential (Anderson & Robertson, 1985; Zorn & Rosenfield, 1989). At no point does a facilitator evaluate an idea, become part of the discussion process, or interject an opinion (Offner, Kramer, & Winter, 1996). To use NGT, a group must follow four steps. The first step involves the silent generation of ideas, with all members recording their responses to a stimulus question or problem. Members must use words or descriptive phrases and list as many opinions or ideas as possible. This step usually takes 3 to 5 minutes but should take no more than 15 to 20 minutes (Gautschi, 1990b). Once the time limit has expired, the facilitator instructs the members to stop writing. The case study's Sarah could exemplify NGT by writing, Give free kids' DVDs with 10 meals as one response to Bean's request of how to regain market share and counter the brand-named toys their company's competitors offer. Iar the content the facilitator records the members' ideas. A critical component of this step is the recording, but not the discussion, of Nominal Group Technique ideas. To execute this step, the facilitator writes members' responses on a blackboard, a flip chart, or newsprint so all members can view them. In a round-robin fashion, the facilitator asks each member to present one idea at a time until all ideas have been recorded. The facilitator helps members determine if their ideas duplicate or extend those ideas already stated. In these cases, the member can elect to piggyback or hitchhike on an existing idea rather than create a new idea. At any time, a member can pass when called upon if he has no more ideas on his list. During the third step, the clarification of ideas, each member must understand what the recorded ideas mean. In response to Sarah's idea in the first step, for example, Joshua could ask if the 10 meals are kids' meals or parents' meals, and the facilitator then would ask Sarah to clarify for the team what she meant by her idea. This process continues until the facilitator feels confident all members understand each idea. The fourth step requires members to vote on the best idea from among the list of ideas generated. This step forces members to take a stand by identifying the most important ideas and then rank-ordering the ideas, which means a member may favor another member's idea and choose not to vote for her own idea. For instance, the members in the case study might be asked to select and rank-order five ideas from the list they generated. Thus, each member not only chooses his or her top five ideas from the list but also must determine the order of these ideas using the ranking system provided by the facilitator. The facilitator then records each member's ranking in front of the group. At this stage, the facilitator could either dismiss the members and present the results to another group for discussion and eventual decision making or explain the voting patterns to the members who generated the ideas and they could begin to discuss the results. "Ethically Speaking: Would it be wrong to vote for your own idea, even though the ideas presented by other group members are stronger, more relevant, or more appropriate?" The strength of this decision-making procedure lies in the short amount of time the group takes to generate, clarify, and vote on the best ideas. Furthermore, a diverse group of working members can participate (Ulschak, Nathanson, & Gillan, 1981). According to consultant and group scholar Carl Moore (1987), NGT is an enjoyable and successful decision-making procedure used in business, government, and community endeavors. On the downside, this procedure requires a facilitator (Ulschak et al., 1981), focuses on one problem only, and limits interaction among group members. Some group members find ideawriting, the third decision-making procedure, enjoyable. This procedure also encourages participation from all members. Ideawriting riting According to Carl Moore (1987), ideawriting focuses on a single topic that produces a written product. Similar to the NGT procedure, ideawriting begins with a writing step. However, its strength lies in the inclusion of silent evaluation of ideas from each group member. To use ideawriting, a group must follow four steps. First, members must react to a stimulus question or problem by listing three or four ideas and then supplying reason(s) why each has merit. Members should not worry about spelling or punctuation and should use phrases. When members finish, they place their list in a pile. Table 7.2 exemplifies a form used in ideawriting. The second step requires members to select a list other than their own and respond to the list. They should read all the ideas and offer solutions, provide suggestions, and identify weaknesses. This process continues until each member has commented on all other members' ideas (i.e., has read all members' lists). The third step requires members to read other members' comments on their list and respond, in writing, to the solutions, suggestions, and weaknesses provided. In this manner, accomplishing criticism of ideas in writing helps neutralize conflict. Table 7.2 Ideawriting Sample Form Table 7.2 Ideawriting Sample Form Name: Problem or Issue: List of ideas: (use phrases) 1. 2. Ideawriting 3. Responses: 1. 2. 3. Source: Moore, C. M. (1987). Group techniques for idea building.Newbury Park,CA: Sage. n the fourth step, members summarize, report, and evaluate their collective ideas and select those they think merit further discussion. They write this summary on a blackboard, a flip chart, or newsprint so all members can see the ideas. Recording the ideas helps the group develop each idea by prompting further discussion. Ideawriting encourages full participation by members and utilizes simultaneous work by members to enhance productivity and efficiency. Additionally, several groups can work on the stimulus question or problem at the same time, and a facilitator quite feasibly can conduct a session with several groups in one room because ideawriting does not take long. Usually, in one hour or less, members generate ideas, have the ideas critiqued, and summarize the main ideas for future discussion. Six Thinking Hats The fourth decision-making procedure comprises six thinking hats. Unlike the aforementioned decision-making procedures, six thinking hats is a technique designed to simplify thinking by having a group focus solely on one aspect of a decision at a time. According to Edward de Bono (1999), often people focus on several aspects at once when thinking about making a decision or solving a problem. These aspects include emotion, logic, wishful thinking, proced Six Thinking Hats ositive and negative consequences. When using six thinking hats as a decision-making procedure, group members examine one aspect of a decision simultaneously from the same point of view based on the collective intelligence, experience, and knowledge of the group. ? In your work group, which hat is most appealing to you? Which hat is least appealing to you? To what degree is this appeal based on your communication and personality traits? In other words, at any given point the group wears one of six color-coded hats, with the color representing one aspect. Table 7.3 identifies the aspect associated with each color. Once the group has examined the decision or problem from one hat, the group proceeds to examine the decision or problem from another hat. Tohle 7 3 Six Thinking Hats Six Thinking Hats Table 7.3 Six Thinking Hats Color Aspect White Approaches the decision in a neutral and objective manner by providing facts and figures Red Approaches the decision in an emotional manner by legitimizing members' emotions and feelings about the decision Black Approaches the decision in a cautious manner by centering on the negative aspects (i.e., risks, differences) of the decision Yellow Approaches the decision in an optimistic manner by focusing on the positive aspects of the decision Green Approaches the decision in a creative manner by exploring alternatives of the decision Blue Approaches the decision in a procedural manner by monitoring the decision-making procedures used by the group Source: Based on de Bono, E. L. (1999). Six thinking hats. New York: Little, Brown and Company. Although there exists no predetermined sequence of hats, de Bono recommends that a group (a) begins with the blue hat, (b) uses at least two ats, and (c) spends no more than 1 minute per member per hat (e.g., a five-member group using three hats would spend approximately 5 ninutes on each aspect, or hat, for a total of approximately 15 minutes). By doing so, a group not only maximizes its thinking on one aspect f a decision or problem; it also can switch between aspects with relative ease and clarity. Why Use Decision-Making Procedures? Using decision-making procedures offers four advantages. First, the rules a group follows in idea generation appear to create other benefits aside from the narrow focus on the quantity of ideas (Kramer, Kuo, & Dailey, 1997). For example, group members trained in decision-making procedures are le- Why Use Decision-making procedures? sitively with each other than group members not trained in decision-making procedures. Even after the idea generation process concludes, the rest of the group process usually becomes more democratic in nature. The second advantage concerns the development of group and member creativity. If you recall from Chapter 1, creativity refers to the process by which members engage in idea generation. To enhance creativity, engage in excursion (Prince, 1970), or a three-stage process that requires group members to (a) put the problem or task out of mind, (b) focus on an irrelevant yet unrelated topic, and (c) force-fit the characteristics of the irrelevant topic to the original problem or task (Weaver & Prince, 1990). In this setting, creativity is considered a skill rather than a talent (Georgiou, 1994) and is based on the definition of creativity as purposeful imagination (Golen, Eure, Titkemeyer, Powers, & Boyer, 1982). Think about how you could enhance decision making in your classroom group if you and your group members subscribed to this consideration. Third, decision-making procedures increase group efficiency (Moore, 1987) and enhance the quality of the decision (Hall & Watson, 1980). Regardless of whether a group uses face-to-face procedures or communicates through e-mail, using these procedures simultaneously forces a group to focus on the task and minimize non-task talk. As you now know, the steps in NGT and ideawriting do not permit task deviation. Furthermore, groups that do not use these procedures may not use their time effectively (Sunwolf & Seibold, 1999) and often think they must solve the problem quickly without taking the time to reach high-quality decisions (Poole, 1991). The fourth advantage to decision-making procedures stems from the fact that facilitators (or leaders) can conduct sessions with a large number of groups. This means that an organization can amass larger data sets, engage a diverse number of employees in the decision-making process, and yet spend less time doing it (Moore, 1987). Groups larger than 7 to 9 members who must make decisions may find a buzz group decision- making procedure helpful (Phillips, 1948). In a buzz group, the larger group breaks into subgroups of 3 to 5 members (i.e., the buzz group). Each buzz group then generates ideas to take to the larger group for discussion and decision making. Using buzz groups facilitates member participation, efficiency, and diversity of opinion. Buzz groups "can also breathe life into a stagnant meeting (Seibold & Krikorian, 1997, p. 301), in which organizational members feel invigorated, validated, and involved. Sessions also can be conducted via virtual groups, enabling members to utilize group decision-making procedures through e-mail, message boards, or chat rooms. Decision-making procedures, however, also present three disadvantages. First, some group experts have argued that researchers have not consistently proven that groups outperform individuals, particularly in brainstorming sessions (Jablin & Seibold, 1978; Seibold & Krikorian, 1997). Second, some group members' communication and personality traits affect their participation in decision-making procedures. For example, in terms of brainstorming, group members who contribute a greater number of ideas tend to be low in communication apprehension, feel more attracted to the brainstorming task and more tolerant of ambiguity, and perceive all members as possessing the same group status (Comadena, 1984; Jablin, Seibold, & Sorenson, 1977; Jablin & Sussman, 1978). Similarly, groups composed of all low-communication- apprehensive members also produce more ideas than groups composed of all high-communication-apprehensive members (Jablin, 1981). Although not known, these findings likely may apply to the other three decision-making procedures as well. Third, some group members may feel restrained by their lack of creativity. Because many people consider themselves better at routine thinking than creative thinking (Georgiou, 1994), they easily become self-conscious when placed in creativity-invoking situations (Gordon, 1961). As such, group members required to engage in creativity sometimes become frustrated or flustered. To combat this feeling, members should remember to value creativity for its own worth and not measure it against an objective standard (Golen et al., 1982). A Final Note About Small Group Decision-Making Procedures When we ask students if the groups to which they belong use these decision-making procedures, most students admit their groups do not use any of them, except some form of brainstorming. And even though some college textbooks mention decision-making procedures and professors may even train students to use them, many college students who work full-time state that their work and social groups fail to use them. Communication professor Marshall Scott Poole (1991) listed several reasons why group members resist using decision-making procedures. For example, some members feel awkward using these procedures, and some members feel these procedures impede the flow of discussion rather than enhance it. Other inhibiting effects on members from the use of decision-making procedures include frustration, boredom, grouphate, and destructive conflict (Sunwolf & Seibold, 1999). The next time you work in a group, we encourage you to (a) think about the advantages of decision-making procedures and (b) actively work toward implementing one of these procedures in your group. You might be surprised at not only the quality of the results your group attains but also the time, energy, and frustration that using these procedures alleviates. Conclusion This chapter introduced you to decision-making procedures, first by offering a definition of decision-making procedures. We then examined four specific decision-making procedures: brainstorming, nominal group technique, ideawriting, and six thinking hats. Finally, we identified the advantages and disadvantages associated with using these decision-making procedures. As you read the next chapter, consider whether your choice to use these decision-making procedures relates to the role you play in a small groupStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts