Question: Based on the illustrative numerical data presented above, how attractive is the JIT proposition from a financial perspective, assuming this simplified quantitative example is typical

Based on the illustrative numerical data presented above, how attractive is the JIT proposition from a financial perspective, assuming this simplified quantitative example is typical of others (work through the calculations to produce your answer).

#Its a mathematical solution. please do this properly, thanks in advance

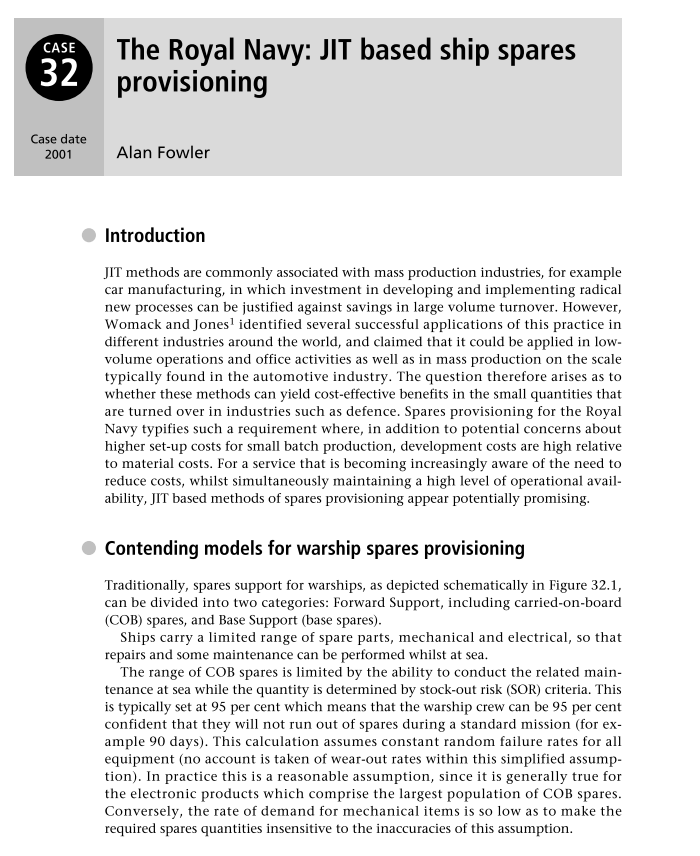

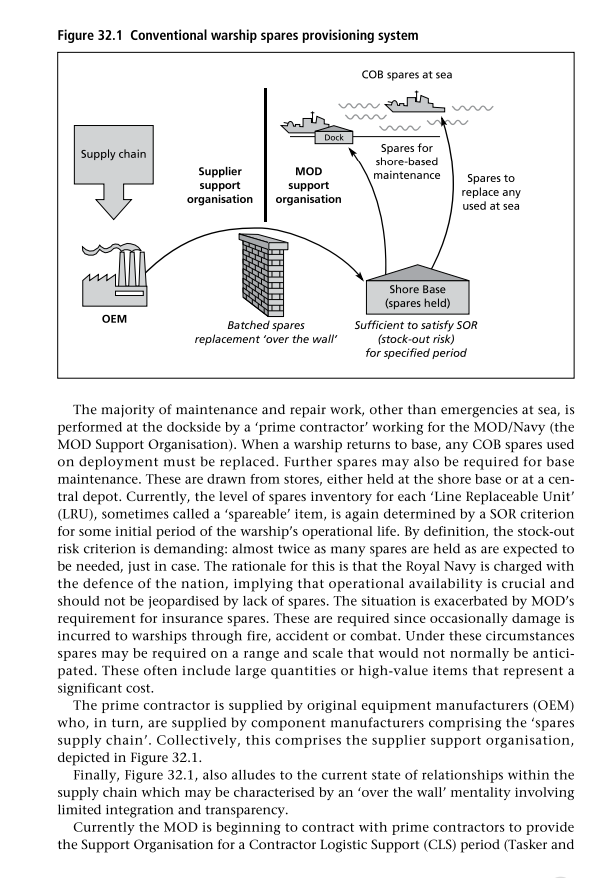

CASE 32 The Royal Navy: JIT based ship spares provisioning Case date 2001 Alan Fowler Introduction JIT methods are commonly associated with mass production industries, for example car manufacturing, in which investment in developing and implementing radical new processes can be justified against savings in large volume turnover. However, Womack and Jones identified several successful applications of this practice in different industries around the world, and claimed that it could be applied in low- volume operations and office activities as well as in mass production on the scale typically found in the automotive industry. The question therefore arises as to whether these methods can yield cost-effective benefits in the small quantities that are turned over in industries such as defence. Spares provisioning for the Royal Navy typifies such a requirement where, in addition to potential concerns about higher set-up costs for small batch production, development costs are high relative to material costs. For a service that is becoming increasingly aware of the need to reduce costs, whilst simultaneously maintaining a high level of operational avail- ability, JIT based methods of spares provisioning appear potentially promising. Contending models for warship spares provisioning Traditionally, spares support for warships, as depicted schematically in Figure 32.1, can be divided into two categories: Forward Support, including carried-on-board (COB) spares, and Base Support (base spares). Ships carry a limited range of spare parts, mechanical and electrical, so that repairs and some maintenance can be performed whilst at sea. The range of COB spares is limited by the ability to conduct the related main- tenance at sea while the quantity is determined by stock-out risk (SOR) criteria. This is typically set at 95 per cent which means that the warship crew can be 95 per cent confident that they will not run out of spares during a standard mission (for ex- ample 90 days). This calculation assumes constant random failure rates for all equipment (no account is taken of wear-out rates within this simplified assump- tion). In practice this is a reasonable assumption, since it is generally true for the electronic products which comprise the largest population of COB spares. Conversely, the rate of demand for mechanical items is so low as to make the required spares quantities insensitive to the inaccuracies of this assumption. Figure 32.1 Conventional warship spares provisioning system COB spares at sea Dock Supply chain Spares for shore-based maintenance Supplier support organisation MOD support organisation Spares to replace any used at sea OEM Batched spares replacement over the wall Shore Base (spares held) Sufficient to satisfy SOR (stock-out risk) for specified period The majority of maintenance and repair work, other than emergencies at sea, is performed at the dockside by a 'prime contractor' working for the MOD/Navy (the MOD Support Organisation). When a warship returns to base, any COB spares used on deployment must be replaced. Further spares may also be required for base maintenance. These are drawn from stores, either held at the shore base or at a cen- tral depot. Currently, the level of spares inventory for each 'Line Replaceable Unit' (LRU), sometimes called a 'spareable item, is again determined by a SOR criterion for some initial period of the warship's operational life. By definition, the stock-out risk criterion is demanding: almost twice as many spares are held as are expected to be needed, just in case. The rationale for this is that the Royal Navy is charged with the defence of the nation, implying that operational availability is crucial and should not be jeopardised by lack of spares. The situation is exacerbated by MOD's requirement for insurance spares. These are required since occasionally damage is incurred to warships through fire, accident or combat. Under these circumstances spares may be required on a range and scale that would not normally be antici- pated. These often include large quantities or high-value items that represent a significant cost. The prime contractor is supplied by original equipment manufacturers (OEM) who, in turn, are supplied by component manufacturers comprising the 'spares supply chain'. Collectively, this comprises the supplier support organisation, depicted in Figure 32.1. Finally, Figure 32.1, also alludes to the current state of relationships within the supply chain which may be characterised by an 'over the wall' mentality involving limited integration and transparency. Currently the MOD is beginning to contract with prime contractors to provide the Support Organisation for a Contractor Logistic Support (CLS) period (Tasker and Willcox_) which corresponds to the period for initial support. During this initial period the actual spares demand is monitored and further spares are ordered as required. However, there are some fundamental problems with this existing system. For example, the initial support period is not long enough to determine future demand; too much stock is procured initially; shortages develop quickly; obsoles- cence problems arise and excessive inventory costs are incurred. Process reconfiguration drawing on JIT principles Figure 32.2 illustrates how a JIT approach to replenishment could enable base-spares inventory to be reduced to give an equivalent SOR but with a shorter replacement lead-time. First, it should be noted that there is no real change at the COB end of the spectrum, except a stronger emphasis on providing timely information when a fail- ure occurs which necessitates a call on spares. Notably the MOD shore base stores are reduced and responsibility for provision- ing is passed further back upstream, moving from a just-in-case to a JIT concept. The system therefore depends upon a fundamental change in the relationship and associated contract with the supplier. This entails arrangement for replacement of spares in a guaranteed lead-time with fixed prices. By adopting this approach based on JIT principles, featuring a shorter replace- ment lead-time, it may be possible to reduce base-spares inventory and tackle the problems outlined above, whilst continuing to provide an equivalent SOR. This also allows insurance spares to be largely eliminated by making alternative arrange- Figure 32.2 JIT based warship spares provisioning Supply chain COB spares at sea Defective items returned direct to supplier Dock Production of Critical Components Supplier decides whether to attempt repair of defective item or to build new? Repair New items items Supplier support organisation MOD support organisation Spares for shore based maintenance & to replace any used at sea Replacements Just-In-Time to maintain SOR at fixed unit cost Reduced inventory Shore Base Suppliers Stores "Hole in (minimal inventory) the wall Finished spares and WIP to satisfy SOR against specified manufacturing lead-time Minimal volume of replacement spares to satisfy SOR against guaranteed delivery lead-time ments for timely replacements in the event that they are needed. This would be achieved by changing the structure of the contract with the supplier whereby instead of a one-off buy of equipment and spares, the supplier would be contracted to provide a service level commitment for a specified period of time. Reduced bureaucracy should also characterise this system. Currently, when defec- tive items are returned to industry for repair or refurbishment, there is a protracted contractual debate about whether it is economical to repair the item, how much this should cost and how long it should take. This debate can often take place between the MOD and several tiers within the supply chain. Consequently it is dispropor- tionately expensive and time-consuming. With the JIT concept, all defective items are simply returned directly to the supplier who then takes the decision on repair independently. Since the supplier is already contracted to provide a replacement in a guaranteed lead-time at a fixed unit price, the customer can be indifferent to the decision outcome. However, the supplier must also provide information on the diagnosis of the failure and any repair activity carried out to maintain 'Corrective Actions' and 'Configuration Management' records. Since it is envisioned that a fixed price would be paid for this service, then the supplier should be motivated to take the most cost-effective decision to maintain margins. Indeed, by assessing the expected number of items that will be capable of repair, and the likely repair costs, the fixed unit price for replacements can be nego- tiated to a weighted average of new build and repair costs with an agreed margin. This means that the aggregate unit price for spares could be less than that paid for the original equipment. Under such a system, the supplier would also be motivated to improve the reliability of its equipment, since this is the other way in which mar- gins can be maintained or improved. In contemplating the potential of such a system, there are a number of current developments which illustrate the trend towards alternative approaches. For ex- ample, there is notable evidence that many in the defence industry are attracted to the idea of moving spares stock from the customer's premises to those of the suppli- ers. This view, which appears to be gaining popularity, is referred to as 'vendor managed inventory' (Walmsley; and Coles). The benefits are seen as reducing the cost of holding the inventory and enabling suppliers to manage inventory levels. However, suppliers naturally expect to be paid for providing this service and taking on additional risk. Furthermore, Coles alludes to doubts over the sincerity of indus- try in its espoused willingness to participate in such projects: 'Only those in industry can truly know whether they are prepared to work in this way, and there is still some way to go before we can confidently predict what the exact result will be.' These initiatives have the potential to facilitate more rapid introduction of new technology into service since the switch to upgrades can render large spares invento- ries obsolete overnight. However, the most significant factor impacting on the more rapid introduction of new technology is the adoption of commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) components. This is because commercial development moves at a rapid pace and is supported by a much larger market. Use of COTS, therefore, enables the MOD to take advantage of new technologies as they emerge without the time and cost penalties of developing bespoke military equipment. Conversely, there are penalties associated with having to accept commercial specifications, which may require concessions on military requirements such as shock resistance. Design must also be modular to allow frequent upgrades in com- ponents to be accepted without affecting form, fit or function. However, on balance, the policies of increasing use of COTS and vendor managed inventory would appear to be entirely complementary with JIT spares provisioning. For example, JIT may be seen to facilitate the more rapid introduction of COTS upgrades by maintaining the supply chain and reducing inventory while COTS components will be more suitable for JIT provisioning because of the larger manu- facturing base and expanded production volumes. These smart procurement policies are mostly enablers for defence projects to achieve greater efficiencies through modern information systems, streamlined bureaucracy and clear data standards. All are potentially significant contributors towards the development of a JIT spares provisioning system, although amongst the various approaches proposed RAMP (rapid acquisition of manufactured parts) appears to be the most relevant. This envisages the holding of electronic parts data and/or partially manufactured components at the suppliers' premises so that they can be completed and shipped quickly when required. In this way, the long lead- times and risks associated with process planning, sourcing exotic materials and elaborate forgings, and organising complex manufacturing processes can be man- aged upstream, leaving the relatively straightforward stages of manufacture to be completed when the parts are required. The MOD pays for the extent of the work completed plus a fee for storage and only completes the balance when the part is actually delivered. Some issues of concern Although the JIT system potentially has several advantages, it is also necessary to sound a cautionary note. The JIT model may work in situations where the account- ing trade-off between the risk of losing a sale, due to the absence of immediate availability, can be balanced with the cost of inventory. The question is, does this logic transfer directly to the case of the defence industry? The MOD is charged with the defence of the realm. What higher priority can there be, and what price can be placed on success? Understandably, the MOD is preoccupied with operational avail- ability as well as cost. A simple trade-off between the costs of the traditional system and those of a JIT system may not be sufficient to justify a change in policy. Additionally, JIT production is usually considered to depend on predictable demand and level scheduling, but both factors are significantly absent in the con- text of spares provisioning. Also, there is the broader issue of whether JIT really eliminates cost from the supply chain or just moves the costs to some point upstream. For example, some evidence indicates that only those suppliers who themselves also implement JIT manufacturing and purchasing techniques are able to supply JIT without increases in raw material and/or finished goods inventory (Germain and Droge). Furthermore, some would say that only where manufactur- ing lead-time is less than the required response time can increases in finished goods inventory be avoided. This highlights the main threat to the application of JIT in the low-volume opera- tions of the Royal Navy. Short response times are required at irregular and unpredictable intervals for the supply of high-value, complex equipment with long manufacturing lead-times. The implication is that this can only be achieved through holding finished goods inventory. In summary, it is essential to remember that still the most significant issue for the MOD, which differentiates it from much of industry, is the importance of oper- ational availability. Achieving a trade-off between inventory cost and availability is a difficult problem to solve. Cost modelling of the spares provisioning process Financial viability is a primary consideration in contemplating a transition to JIT based spares provisioning. Towards this end, a limited modelling exercise may be readily conducted using available suppliers' data on component cost, reliability and production lead-time. Extending this context, it is also important to ask the question: What happens after the initial in-service support period? With the con- ventional approach, the stock level would be topped up to restore the desired SOR for some follow-on period, taking account of the actual demand rate experienced during the initial in-service support period. For analysis to proceed, it would have to be assumed that the predicted failure rate is accurate so that the predicted demand rate, after the initial period, can be expected to remain unchanged. JIT replacements would then continue to be provided, as before, with prices assumed to remain stable. Furthermore, the advantage of the JIT based approach could actually be enhanced further when factors such as obsolescence and technology upgrading are taken into account. This is because with JIT, accommodating changes to the in- service equipment configuration is easier, quicker and cheaper because there is less inventory to become obsolete. Finally, it must always be emphasised that the operational availability of vessels is of paramount importance to the MOD. Consequently, it is imperative when compar- ing the resulting spares availability under the two competing policies, to bear in mind that the availability of spares must remain at least as good as it is at present and, ideally, should actually be improved following the implementation of a JIT policy. A comparative illustration of a typical spares provisioning situation Presented below is a snapshot of some typical data pertaining to spares provisioning for warships. The Royal Navy is considering the alternative JIT based approach as a means of potentially reducing the cost of spares inventory and is using, as an ex- ample, the case of a particular high-tech part for a radar system. This is supplied by a single supplier who does not supply anything else to the Navy. Under the existing arrangements, the Navy carries two years' stock whilst also subscribing to the 95 per cent stock-out risk criterion (this means that there is a 95 per cent confidence of not running out of spares). Alternatively, this may be thought of as a 95 per cent 'stock-held' confidence criterion. In addition, Naval operational requirements dictate that, irrespective of risk criteria based on probability, there should be a minimum inventory level of one item to provide for immediate availability. Under the alternative JIT based spares policy that is being considered, the cus- tomer (the Navy/MOD in this case) will hold reduced stock at its shore base, while still achieving 95 per cent SOR against a guarantee of delivery on demand to the Navy, within five days, at a fixed unit price. The supplier will also maintain addi- tional buffer stock, at an agreed level, to achieve 95 per cent SOR against its manufacturing lead-time, to maintain availability (replacing any parts drawn down by the Navy during the support period). This service will be provided, in return for a fixed fee to be agreed between customer and supplier. It is assumed that any failed parts will be discarded. For the purpose of calculation, the following customer data is available: There is one of these parts fitted on each of 10 ships. The anticipated utilisation is 1000 operating hours per year for each part. The mean time between failure (MTBF) of these parts is 10000 operating hours. The following supplier data is also available: The supplier has a manufacturing lead-time of 90 days. The cost of each part to the supplier is 100000. This is marked up by 10 per cent for sale to the Navy. The supplier proposes to charge a fee of 35 000 per annum to the Navy for pro- viding the JIT type service, plus the initial cost of setting up the buffer stock. The contract will run for two years (to be directly comparable with the existing arrangements). In comparing the JIT based proposal with the existing arrangements, the follow- ing questions thereby arise: (a) What is the cost to the Navy in the existing, traditional arrangement, when there is a need to carry two years' stock in accordance with the 95 per cent stock-out risk criterion? (b) Under the alternative JIT arrangement, what level of stock needs to be carried by the Navy and by the supplier respectively? What will this arrangement cost the Navy, in total? (c) Is the proposed JIT arrangement financially advantageous to both the Navy and the supplier (that is, what are the respective profits/benefits)? (d) Suppose that a sensitivity analysis is also to be performed in which the mean time between failure is assumed to be respectively: - 1000 operating hours. - 20000 operating hours. How does this affect the predictions of benefits/deficits accruing to the respec- tive parties? (e) Are there any other sensitivities that should be considered and how influential are they with respect to the viability of the proposal? In performing the above analysis it should be assumed that cumulative Poisson prob- ability data will be used to assess the value of the stock-out risk criterion for different scenarios. In performing your calculations you may choose, for convenience, to use the cumulative Poisson function provided in the standard Excel spreadsheet facility. CASE 32 The Royal Navy: JIT based ship spares provisioning Case date 2001 Alan Fowler Introduction JIT methods are commonly associated with mass production industries, for example car manufacturing, in which investment in developing and implementing radical new processes can be justified against savings in large volume turnover. However, Womack and Jones identified several successful applications of this practice in different industries around the world, and claimed that it could be applied in low- volume operations and office activities as well as in mass production on the scale typically found in the automotive industry. The question therefore arises as to whether these methods can yield cost-effective benefits in the small quantities that are turned over in industries such as defence. Spares provisioning for the Royal Navy typifies such a requirement where, in addition to potential concerns about higher set-up costs for small batch production, development costs are high relative to material costs. For a service that is becoming increasingly aware of the need to reduce costs, whilst simultaneously maintaining a high level of operational avail- ability, JIT based methods of spares provisioning appear potentially promising. Contending models for warship spares provisioning Traditionally, spares support for warships, as depicted schematically in Figure 32.1, can be divided into two categories: Forward Support, including carried-on-board (COB) spares, and Base Support (base spares). Ships carry a limited range of spare parts, mechanical and electrical, so that repairs and some maintenance can be performed whilst at sea. The range of COB spares is limited by the ability to conduct the related main- tenance at sea while the quantity is determined by stock-out risk (SOR) criteria. This is typically set at 95 per cent which means that the warship crew can be 95 per cent confident that they will not run out of spares during a standard mission (for ex- ample 90 days). This calculation assumes constant random failure rates for all equipment (no account is taken of wear-out rates within this simplified assump- tion). In practice this is a reasonable assumption, since it is generally true for the electronic products which comprise the largest population of COB spares. Conversely, the rate of demand for mechanical items is so low as to make the required spares quantities insensitive to the inaccuracies of this assumption. Figure 32.1 Conventional warship spares provisioning system COB spares at sea Dock Supply chain Spares for shore-based maintenance Supplier support organisation MOD support organisation Spares to replace any used at sea OEM Batched spares replacement over the wall Shore Base (spares held) Sufficient to satisfy SOR (stock-out risk) for specified period The majority of maintenance and repair work, other than emergencies at sea, is performed at the dockside by a 'prime contractor' working for the MOD/Navy (the MOD Support Organisation). When a warship returns to base, any COB spares used on deployment must be replaced. Further spares may also be required for base maintenance. These are drawn from stores, either held at the shore base or at a cen- tral depot. Currently, the level of spares inventory for each 'Line Replaceable Unit' (LRU), sometimes called a 'spareable item, is again determined by a SOR criterion for some initial period of the warship's operational life. By definition, the stock-out risk criterion is demanding: almost twice as many spares are held as are expected to be needed, just in case. The rationale for this is that the Royal Navy is charged with the defence of the nation, implying that operational availability is crucial and should not be jeopardised by lack of spares. The situation is exacerbated by MOD's requirement for insurance spares. These are required since occasionally damage is incurred to warships through fire, accident or combat. Under these circumstances spares may be required on a range and scale that would not normally be antici- pated. These often include large quantities or high-value items that represent a significant cost. The prime contractor is supplied by original equipment manufacturers (OEM) who, in turn, are supplied by component manufacturers comprising the 'spares supply chain'. Collectively, this comprises the supplier support organisation, depicted in Figure 32.1. Finally, Figure 32.1, also alludes to the current state of relationships within the supply chain which may be characterised by an 'over the wall' mentality involving limited integration and transparency. Currently the MOD is beginning to contract with prime contractors to provide the Support Organisation for a Contractor Logistic Support (CLS) period (Tasker and Willcox_) which corresponds to the period for initial support. During this initial period the actual spares demand is monitored and further spares are ordered as required. However, there are some fundamental problems with this existing system. For example, the initial support period is not long enough to determine future demand; too much stock is procured initially; shortages develop quickly; obsoles- cence problems arise and excessive inventory costs are incurred. Process reconfiguration drawing on JIT principles Figure 32.2 illustrates how a JIT approach to replenishment could enable base-spares inventory to be reduced to give an equivalent SOR but with a shorter replacement lead-time. First, it should be noted that there is no real change at the COB end of the spectrum, except a stronger emphasis on providing timely information when a fail- ure occurs which necessitates a call on spares. Notably the MOD shore base stores are reduced and responsibility for provision- ing is passed further back upstream, moving from a just-in-case to a JIT concept. The system therefore depends upon a fundamental change in the relationship and associated contract with the supplier. This entails arrangement for replacement of spares in a guaranteed lead-time with fixed prices. By adopting this approach based on JIT principles, featuring a shorter replace- ment lead-time, it may be possible to reduce base-spares inventory and tackle the problems outlined above, whilst continuing to provide an equivalent SOR. This also allows insurance spares to be largely eliminated by making alternative arrange- Figure 32.2 JIT based warship spares provisioning Supply chain COB spares at sea Defective items returned direct to supplier Dock Production of Critical Components Supplier decides whether to attempt repair of defective item or to build new? Repair New items items Supplier support organisation MOD support organisation Spares for shore based maintenance & to replace any used at sea Replacements Just-In-Time to maintain SOR at fixed unit cost Reduced inventory Shore Base Suppliers Stores "Hole in (minimal inventory) the wall Finished spares and WIP to satisfy SOR against specified manufacturing lead-time Minimal volume of replacement spares to satisfy SOR against guaranteed delivery lead-time ments for timely replacements in the event that they are needed. This would be achieved by changing the structure of the contract with the supplier whereby instead of a one-off buy of equipment and spares, the supplier would be contracted to provide a service level commitment for a specified period of time. Reduced bureaucracy should also characterise this system. Currently, when defec- tive items are returned to industry for repair or refurbishment, there is a protracted contractual debate about whether it is economical to repair the item, how much this should cost and how long it should take. This debate can often take place between the MOD and several tiers within the supply chain. Consequently it is dispropor- tionately expensive and time-consuming. With the JIT concept, all defective items are simply returned directly to the supplier who then takes the decision on repair independently. Since the supplier is already contracted to provide a replacement in a guaranteed lead-time at a fixed unit price, the customer can be indifferent to the decision outcome. However, the supplier must also provide information on the diagnosis of the failure and any repair activity carried out to maintain 'Corrective Actions' and 'Configuration Management' records. Since it is envisioned that a fixed price would be paid for this service, then the supplier should be motivated to take the most cost-effective decision to maintain margins. Indeed, by assessing the expected number of items that will be capable of repair, and the likely repair costs, the fixed unit price for replacements can be nego- tiated to a weighted average of new build and repair costs with an agreed margin. This means that the aggregate unit price for spares could be less than that paid for the original equipment. Under such a system, the supplier would also be motivated to improve the reliability of its equipment, since this is the other way in which mar- gins can be maintained or improved. In contemplating the potential of such a system, there are a number of current developments which illustrate the trend towards alternative approaches. For ex- ample, there is notable evidence that many in the defence industry are attracted to the idea of moving spares stock from the customer's premises to those of the suppli- ers. This view, which appears to be gaining popularity, is referred to as 'vendor managed inventory' (Walmsley; and Coles). The benefits are seen as reducing the cost of holding the inventory and enabling suppliers to manage inventory levels. However, suppliers naturally expect to be paid for providing this service and taking on additional risk. Furthermore, Coles alludes to doubts over the sincerity of indus- try in its espoused willingness to participate in such projects: 'Only those in industry can truly know whether they are prepared to work in this way, and there is still some way to go before we can confidently predict what the exact result will be.' These initiatives have the potential to facilitate more rapid introduction of new technology into service since the switch to upgrades can render large spares invento- ries obsolete overnight. However, the most significant factor impacting on the more rapid introduction of new technology is the adoption of commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) components. This is because commercial development moves at a rapid pace and is supported by a much larger market. Use of COTS, therefore, enables the MOD to take advantage of new technologies as they emerge without the time and cost penalties of developing bespoke military equipment. Conversely, there are penalties associated with having to accept commercial specifications, which may require concessions on military requirements such as shock resistance. Design must also be modular to allow frequent upgrades in com- ponents to be accepted without affecting form, fit or function. However, on balance, the policies of increasing use of COTS and vendor managed inventory would appear to be entirely complementary with JIT spares provisioning. For example, JIT may be seen to facilitate the more rapid introduction of COTS upgrades by maintaining the supply chain and reducing inventory while COTS components will be more suitable for JIT provisioning because of the larger manu- facturing base and expanded production volumes. These smart procurement policies are mostly enablers for defence projects to achieve greater efficiencies through modern information systems, streamlined bureaucracy and clear data standards. All are potentially significant contributors towards the development of a JIT spares provisioning system, although amongst the various approaches proposed RAMP (rapid acquisition of manufactured parts) appears to be the most relevant. This envisages the holding of electronic parts data and/or partially manufactured components at the suppliers' premises so that they can be completed and shipped quickly when required. In this way, the long lead- times and risks associated with process planning, sourcing exotic materials and elaborate forgings, and organising complex manufacturing processes can be man- aged upstream, leaving the relatively straightforward stages of manufacture to be completed when the parts are required. The MOD pays for the extent of the work completed plus a fee for storage and only completes the balance when the part is actually delivered. Some issues of concern Although the JIT system potentially has several advantages, it is also necessary to sound a cautionary note. The JIT model may work in situations where the account- ing trade-off between the risk of losing a sale, due to the absence of immediate availability, can be balanced with the cost of inventory. The question is, does this logic transfer directly to the case of the defence industry? The MOD is charged with the defence of the realm. What higher priority can there be, and what price can be placed on success? Understandably, the MOD is preoccupied with operational avail- ability as well as cost. A simple trade-off between the costs of the traditional system and those of a JIT system may not be sufficient to justify a change in policy. Additionally, JIT production is usually considered to depend on predictable demand and level scheduling, but both factors are significantly absent in the con- text of spares provisioning. Also, there is the broader issue of whether JIT really eliminates cost from the supply chain or just moves the costs to some point upstream. For example, some evidence indicates that only those suppliers who themselves also implement JIT manufacturing and purchasing techniques are able to supply JIT without increases in raw material and/or finished goods inventory (Germain and Droge). Furthermore, some would say that only where manufactur- ing lead-time is less than the required response time can increases in finished goods inventory be avoided. This highlights the main threat to the application of JIT in the low-volume opera- tions of the Royal Navy. Short response times are required at irregular and unpredictable intervals for the supply of high-value, complex equipment with long manufacturing lead-times. The implication is that this can only be achieved through holding finished goods inventory. In summary, it is essential to remember that still the most significant issue for the MOD, which differentiates it from much of industry, is the importance of oper- ational availability. Achieving a trade-off between inventory cost and availability is a difficult problem to solve. Cost modelling of the spares provisioning process Financial viability is a primary consideration in contemplating a transition to JIT based spares provisioning. Towards this end, a limited modelling exercise may be readily conducted using available suppliers' data on component cost, reliability and production lead-time. Extending this context, it is also important to ask the question: What happens after the initial in-service support period? With the con- ventional approach, the stock level would be topped up to restore the desired SOR for some follow-on period, taking account of the actual demand rate experienced during the initial in-service support period. For analysis to proceed, it would have to be assumed that the predicted failure rate is accurate so that the predicted demand rate, after the initial period, can be expected to remain unchanged. JIT replacements would then continue to be provided, as before, with prices assumed to remain stable. Furthermore, the advantage of the JIT based approach could actually be enhanced further when factors such as obsolescence and technology upgrading are taken into account. This is because with JIT, accommodating changes to the in- service equipment configuration is easier, quicker and cheaper because there is less inventory to become obsolete. Finally, it must always be emphasised that the operational availability of vessels is of paramount importance to the MOD. Consequently, it is imperative when compar- ing the resulting spares availability under the two competing policies, to bear in mind that the availability of spares must remain at least as good as it is at present and, ideally, should actually be improved following the implementation of a JIT policy. A comparative illustration of a typical spares provisioning situation Presented below is a snapshot of some typical data pertaining to spares provisioning for warships. The Royal Navy is considering the alternative JIT based approach as a means of potentially reducing the cost of spares inventory and is using, as an ex- ample, the case of a particular high-tech part for a radar system. This is supplied by a single supplier who does not supply anything else to the Navy. Under the existing arrangements, the Navy carries two years' stock whilst also subscribing to the 95 per cent stock-out risk criterion (this means that there is a 95 per cent confidence of not running out of spares). Alternatively, this may be thought of as a 95 per cent 'stock-held' confidence criterion. In addition, Naval operational requirements dictate that, irrespective of risk criteria based on probability, there should be a minimum inventory level of one item to provide for immediate availability. Under the alternative JIT based spares policy that is being considered, the cus- tomer (the Navy/MOD in this case) will hold reduced stock at its shore base, while still achieving 95 per cent SOR against a guarantee of delivery on demand to the Navy, within five days, at a fixed unit price. The supplier will also maintain addi- tional buffer stock, at an agreed level, to achieve 95 per cent SOR against its manufacturing lead-time, to maintain availability (replacing any parts drawn down by the Navy during the support period). This service will be provided, in return for a fixed fee to be agreed between customer and supplier. It is assumed that any failed parts will be discarded. For the purpose of calculation, the following customer data is available: There is one of these parts fitted on each of 10 ships. The anticipated utilisation is 1000 operating hours per year for each part. The mean time between failure (MTBF) of these parts is 10000 operating hours. The following supplier data is also available: The supplier has a manufacturing lead-time of 90 days. The cost of each part to the supplier is 100000. This is marked up by 10 per cent for sale to the Navy. The supplier proposes to charge a fee of 35 000 per annum to the Navy for pro- viding the JIT type service, plus the initial cost of setting up the buffer stock. The contract will run for two years (to be directly comparable with the existing arrangements). In comparing the JIT based proposal with the existing arrangements, the follow- ing questions thereby arise: (a) What is the cost to the Navy in the existing, traditional arrangement, when there is a need to carry two years' stock in accordance with the 95 per cent stock-out risk criterion? (b) Under the alternative JIT arrangement, what level of stock needs to be carried by the Navy and by the supplier respectively? What will this arrangement cost the Navy, in total? (c) Is the proposed JIT arrangement financially advantageous to both the Navy and the supplier (that is, what are the respective profits/benefits)? (d) Suppose that a sensitivity analysis is also to be performed in which the mean time between failure is assumed to be respectively: - 1000 operating hours. - 20000 operating hours. How does this affect the predictions of benefits/deficits accruing to the respec- tive parties? (e) Are there any other sensitivities that should be considered and how influential are they with respect to the viability of the proposal? In performing the above analysis it should be assumed that cumulative Poisson prob- ability data will be used to assess the value of the stock-out risk criterion for different scenarios. In performing your calculations you may choose, for convenience, to use the cumulative Poisson function provided in the standard Excel spreadsheet facility

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts