Question: can you please help with this case study, im lost. ive attatched all reading in order as well as the directions. CASE 15.1 The Parable

can you please help with this case study, im lost. ive attatched all reading in order as well as the directions.

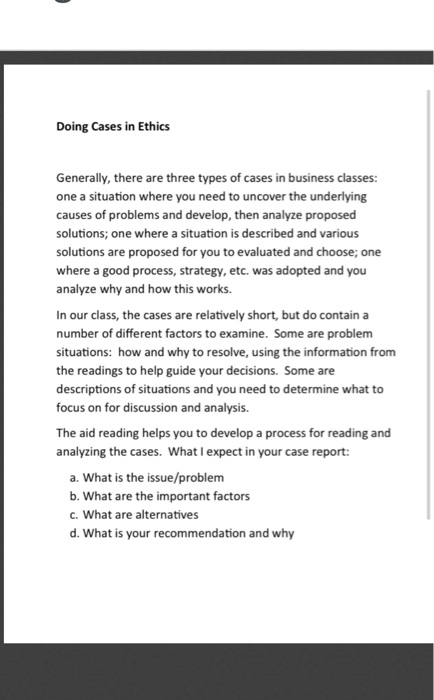

CASE 15.1 The Parable of the Sadhu Bowen H. McCoy Bowen H. McCoy is a managing director of Morgan Six years earlier I had suffered pulmonary edema, Stanley & Co., Inc., and president of Morgan Stanley an acute form of altitude sickness, at 16,500 feet in Realty, Inc. He is also an ordained ruling elder of the the vicinity of Everest base camp, so we were un- United Presbyterian Church. derstandably concerned about what would happen at Last year, as the first participant in the new six-month 18,000 feet. Moreover, the Himalayas were having sabbatical program that Morgan Stanley has adopted, their wettest spring in 20 years; hip-deep powder and I enjoyed a rare opportunity to collect my thoughts ice had already driven us off one ridge. If we failed as well as do some traveling. I spent the first three to cross the pass, I feared that the last half of our months in Nepal, walking 600 miles through 200 vil "once in a lifetime" trip would be ruined. lages in the Himalayas and climbing some 120,000 The night before we would try the pass, we vertical feet. On the trip my sole Western companion camped at a hut at 14,500 feet. In the photos taken was an anthropologist who shed light on the cultural at that camp, my face appears wan. The last village patterns of the villages we passed through. we'd passed through was a sturdy two-day walk During the Nepal hike, something occurred that below us, and I was tired. has had a powerful impact on my thinking about During the late afternoon, four back-packers from corporate ethics. Although some might argue that New Zealand joined us, and we spent most of the the experience has no relevance to business, it was a night awake, anticipating the climb. Below we could situation in which a basic ethical dilemma suddenly see the fires of two other parties, which turned out intruded into the lives of a group of individuals. How to be two Swiss couples and a Japanese hiking club. the group responded I think holds a lesson for all To get over the steep part of the climb before the organizations no matter how defined. sun melted the steps cut in the ice, we departed at 3:30 A.m. The New Zealanders left first, followed by THE SADHU Stephen and myself, our porters and Sherpas, and then the Swiss. The Japanese lingered in their camp. The Nepal experience was more rugged and adven- The sky was clear, and we were confident that no turesome than I had anticipated. Most commercial spring storm would erupt that day to close the pass. treks last two or three weeks and cover a quarter of At 15,500 feet, it looked to me as if Stephen were the distance we traveled. shuffling and staggering a bit, which are symptoms My friend Stephen, the anthropologist, and I were of altitude sickness. (The initial stage of altitude sick- halfway through the 60-day Himalayan part of the trip ness brings a headache and nausea. As the condition when we reached the high point, an 18,000-foot pass worsens, a climber may encounter difficult breathing, over a crest that we'd have to traverse to reach to the vil disorientation, aphasia, and paralysis.) I felt strong, lage of Muklinath, an ancient holy place for pilgrims. my adrenaline was flowing, but I was very concerned From Harvard Business Review, Sept-Oct 1983, pp. 103-104. Reprinted with permission. THE GOOD LIFE 599 about my ultimate ability to get across. A couple of our porters were also suffering from the height, and Pasang, our Sherpa sirdar (leader), was worried. Just after daybreak, while we rested at 15,500 feet, one of the New Zealanders, who had gone ahead, came staggering down toward us with a body slung across his shoulders. He dumped the almost naked, barefoot body of an Indian holy mana sadhu-at my feet. He had found the pilgrim lying on the ice, shivering and suffering from hypothermia. I cradled the sadhu's head and laid him out on the rocks. The New Zealander was angry. He wanted to get across the pass before the bright sun melted the snow. He said, Look, I've done what I can. You have porters and Sherpa guides. You care for him. We're going on!" He turned and went back up the mountain to join his friends. I took a carotid pulse and found that the sadhu was still alive. We figured he had probably visited the holy shrines at Muklinath and was on his way home. It was fruitless to question why he had chosen this desperately high route instead of the safe, heav- ily traveled caravan route through the Kali Gandaki gorge. Or why he was almost naked and with no shoes, or how long he had been lying in the pass. The answers weren't going to solve our problem. Stephen and the four Swiss began stripping off outer clothing and opening their packs. The sadhu was soon clothed from head to foot. He was not able to walk, but he was very much alive. I looked down the mountain and spotted below the Japanese climb- ers marching up with a horse. Without a great deal of thought, I told Stephen and Pasang that I was concerned about withstand- ing the heights to come and wanted to get over the pass. I took off after several of our porters who had gone ahead. To: You From: The Philosopher Subject: "A Happiness Box" You wrote in your last e-mail message, All I want is to be happy and enjoy my life!" I detect some frustration in that outburst. But is that all that you really want out of life? I was thinking the other day: imagine an inventionwhich today is not at all implausiblethat is the following. It is a box, cushioned and comfortable (not unlike a coffin, but don't let that association turn you off). You lie in the box, and we hook you up with electrodes, but nothing painful or discomforting and after a few minutes you forget that they are even there. The electrodes are connected to a computer that sends out signals that stimulate your brain, sending waves of pleasure and satisfaction. Within minutes, you completely stop caring about anything else. No worries, no problems. Of course, you can get out of the box anytime that you want to, but it isn't necessary because technicians take care of all your bodily needs, making sure you have water and nutrition, that your body stays at a healthy temperature, and so on. And as a matter of fact (we can imagine), no one has ever decided to get out of the box. With time, your body starts looking like a bean bag from lack of exercise, and your friends and family all forget about you, but you don't care. You're happy. You're completely satisfied with your life and enjoying every minute of it. OK. There's your life of enjoyment, satisfaction, and happiness. Would you like to try out the box? ciu97682_ch15_575-602.indd 599 04/24/18 06:27 PM 600 HONEST WORK have to exert all their energy to get themselves over the pass. He had thought they could not carry a man down 1,000 feet to the hut, reclimb the slope, and get across safely before the snow melted. Pasang had pressed Stephen not to delay any longer. The Sherpas had carried the sadhu down to a rock in the sun at about 15,000 feet and had pointed out the hut another 500 feet below. The Japanese had given him food and drink. When they had last seen him he was listlessly throwing rocks at the Japanese party's dog, which had frightened him. We do not know if the sadhu lived or died. On the steep part of the ascent where, if the ice steps had given way, I would have slid down about 3,000 feet, I felt vertigo. I stopped for a breather, allowing the Swiss to catch up with me. I inquired about the sadhu and Stephen. They said that the sadhu was fine and that Stephen was just behind. I set off again for the summit. Stephen arrived at the summit an hour after I did. Still exhilarated by victory, I ran down the snow slope to congratulate him. He was suffering from altitude sickness, walking 15 steps, then stopping, walking 15 steps, then stopping. Pasang accompa- nied him all the way up. When I reached them, Ste- phen glared at me and said: "How do you feel about contributing to the death of a fellow man?" I did not fully comprehend what he meant. "Is the sadhu dead?" I inquired. "No," replied Stephen, but he surely will be!" After I had gone, and the Swiss had departed not long after, Stephen had remained with the sadhu. When the Japanese had arrived, Stephen had asked to use their horse to transport the sadhu down to the hut. They had refused. He had then asked Pasang to have a group of our porters carry the sadhu. Pasang had resisted the idea, saying that the porters would QUESTIONS 1. Who is responsible for the well-being of the sadhu? What are the duties of the people involved? What action would best serve the good of everyone? 2. How are the problems here similar to problems that arise in organizations every day? What kinds of sadhus do people confront in everyday life? 3. Would McCoy's group have behaved differently if they had come across a Western man rather than a sadhu? 4. What if the sadhu told the climbers that he wanted to die? Would you feel comfortable letting him? Doing Cases in Ethics Generally, there are three types of cases in business classes: one a situation where you need to uncover the underlying causes of problems and develop, then analyze proposed solutions; one where a situation is described and various solutions are proposed for you to evaluated and choose; one where a good process, strategy, etc. was adopted and you analyze why and how this works. In our class, the cases are relatively short, but do contain a number of different factors to examine. Some are problem situations: how and why to resolve, using the information from the readings to help guide your decisions. Some are descriptions of situations and you need to determine what to focus on for discussion and analysis. The aid reading helps you to develop a process for reading and analyzing the cases. What I expect in your case report: a. What is the issue/problem b. What are the important factors c. What are alternatives d. What is your recommendation and why