Question: Case study of the Inside-out Prison Exchange Program: Impact on Stakeholders. Please have detailed answers thanks! It was late May 2018, and Lori Pompa, founder

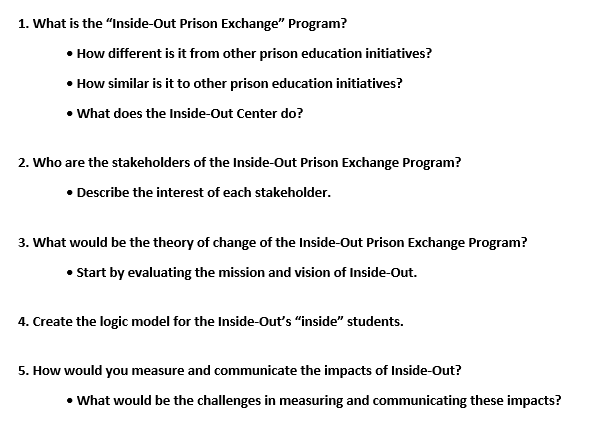

Case study of the "Inside-out" Prison Exchange Program: Impact on Stakeholders.

Please have detailed answers thanks!

It was late May 2018, and Lori Pompa, founder of the Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program (Inside-Out) and executive director of the Inside-Out Center at Temple University in Philadelphia, was exhausted. She had just wrapped up her 21st year of teaching college courses within Philadelphia prisons through Inside-Out. Now she needed to prepare for the summer. Inside-Out's busiest season for intemational instructor training. As Pompa reflected on the past year, she knew she needed to raise more funds to support the program's vital work and hire additional staff. University students and incarcerated students alike regularly referred to the course as having been life-changing. Program participants around the country were so passionate about the experience that, even after leaving the program they continued meeting regularly in Inside-Out "Think Tanks to echicate their communities and advocate for prison system reform. Faculty from the Inside-Out Instructor Training Program reported that the training had revived their passion for teaching, and prisons participating in Inside-Out noted improvements in the behaviour and mental health of the incarcerated students. Despite the success stories, Pompa knew it would take more than anecdotal evidence to gain new finders. Prison education finding was competitive, and foundations and individual donors increasingly required tangible impact measurements to demonstrate program efficacy. Gathering that data within the strict boundaries of the prison system would be a challenge, and might call into question the efforts and effectiveness of the Inside-Out Network membershundreds of colleges, universities, sponsors, and instructors. Assessing long-term impacts seemed nearly impossible because it was difficult to keep track of participants as they graduated from the college program or completed their prison sentences and returned to the outside world. Plus, as Pompa looked ahead to the upcoming summer, she knew any measurement efforts would need to be extremely cost-efficient. Without the finding to hire extra staff, she and her existing team were already stretched thin. CREATING INSIDE-OUT When Pompa joined Temple University's Criminal Justice Department as teaching faculty in 1992, she made prison visits a regular part of her curriculum "Part of my personal mission is to get as many people to visit inside prisons and jails as possible," Pompa said. "We as a society are only able to continue to incarcerate 2.2 million people because so many of us don't know what's going on Getting people to visit inside prisons is one of the ways that change is going to happen." Pompa had spent years working in prisons and becoming familiar with the landscape. Still, she found herself surprised by the impact of these prison visits. One day, a few years into teaching, I remember taking my students to speak to a panel of men who were serving life sentences in prison." The discussion quickly moved beyond basic criminology questions. We talked about crime and justice and race and class and politics and economicsand how it was all interwoven. Up to that point. I had never had this powerful of a discussion anywhere." Following the discussion, one of the men from the panel suggested that Pompa teach an entire course within a prison for both incarcerated and university students. Pompa couldn't get the idea out of her head. She began planning and negotiating with prison and university officials, and two years later she offered the first full-semester course at a local jail. Each week. 15 university students ("outside students) came to a jail to meet with 15 incarcerated students (inside" students). She recalled: At first, I was really focused on what we could learn together about crime and justice. What I didn't expect was the other leaming that unfolded before my eyes. People were learning about themselves, about communication about conflict and about society and their relationship to society in a totally different way. One inside student agreed: I started seeing things I could do. In the eight years I've been incarcerated, I've never felt so strong about wanting to make a change." DESIGNING A SUCCESSFUL CURRICULUM Each Inside-Out course involved equal numbers of inside and outside students meeting weekly inside a prison or jail Students sat in a circle, with inside and outside students altemating. What this circle represents is an opportunity to bring people back into the community," said Pompa She screened all of the students, both inside and outside, prior to admission to ensure that they could handle the workload and the unique social demands of the course. "I was so trying to be at ease," said one outside student, recalling her first day in the course. "But as soon as the inside students) entered the classroom you didn't have to try, because everyone was so amiable."? Pompa was clear about the goals of the Inside-Out courses: "We were not going in to study the folks on the inside. We were not going in to help them; nobody asked us for help. We were not advocating for them in any way.... It was really studying together." Pompa stayed in the background as much as possible, facilitating conversations between the students to help them learn from each other. The students completed coursework around a central theme, such as criminology or sociology, but discussions naturally diverged into a wide range of issues, including race, poverty, education and students' experiences inside and outside of the walls. They come in seeing us as criminals," one inside student said, reflecting on an ethics course he took, and we may see them as people in school or the outside world or whatever... but the point of ethics is to see past that and to see the actual person. It fits for the class because there's two different worlds coming into this class trying to learn the same thing. ** Correctional facilities kept a close eye on programs such as Inside-Out that operated within their walls. Prison wardens were highly interconnected, and bad news travelled quickly. "I've seen really wonderful programs get shut down because people bring in contraband or people fall in love or something occurs," Pompa said. "We cannot afford for that to happen. Period." To protect these boundaries, the only personal information exchanged by students was their first names. Students agreed not to contact one another outside of class, even after completing the course. "You go into this class knowing that you can never be in contact with the inside students again," one outside student recalled. And leaving on the last day was saying goodbye forever. Honestly, I think that's the hardest thing I've ever done." Thanks to these boundaries, Inside-Out had not had any major incidents in its 21-year history, but Pompa knew it was an ongoing risk "If anything bad were to happenan injury or accident-correctional facilities could get rid of the program in a heartbeat." GLOBAL EXPANSION When Pompa first began teaching Inside-Out classes, the program met in a jail in Philadelphia. Because those in jail had relatively short sentences, some of the inside students were released midway through the course each semester, which disrupted classes and leaming. In 2002, Pompa had the opportunity to move her courses to Graterford Prison, a maximum-security prison located an hour's drive outside of Philadelphia. Due to the longer sentences that people served in prison inside students at Graterford could commit to full-semester courses, and the classroom discussions became even richer. When Pompa's first course at Graterford ended, none of her students wanted to stop meeting. They decided to continue coming together weekly and became the "Graterford Think Tank" a critical guiding and advising body for the Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program By 2018, the Graterford Think Tank had been meeting weekly for over 16 years. Following Pompa's initial success, two colleagues from Temple University approached her about teaching their subjects through Inside-Out and expanding the program within Philadelphia. Later, the Graterford Think Tank suggested expanding the Inside-Out Program nationally. To coordinate the expansion, Pompa founded the Inside-Out Center and became its executive director. In 2003, Pompa received a Soros Justice Senior Fellowship to find the expansion and in July 2004, the Inside-Out Center offered its first training session for faculty from other universities. We were afraid that nobody would come because it was too weird an idea," Pompa recalled "We were hoping for maybe 10 to 12 people. We got 20 people in the first training from all over the country:"7 Instructor training classes consisted of 15-20 faculty who spent 60 hours over seven days discussing course structure, completing team projects, and meeting with the Think Tank inside of the prison to talk through curricular and diversity issues. "You cannot go in without preparation," said Pompa. "Instructors must know the language prisons use and what questions to ask." The instructor training sessions cost $2,700$ and centred on Inside-Out's unique, dialogue-based approach to education, which emphasized leaming how to communicate deeply across large social differences. In an Inside-Out learning circle,"students on both sides have a voice in the world despite their different opinions," said Interim Executive Director David Krueger, "and this method of dialogue is important to creating basic values of civic conversation." The instructor training proved to be very successful, not only for preparing faculty to facilitate Inside-Out classes but also to encourage deeper exploration of what it meant to teach "It was very experientially oriented. said Wade Deisman, a professor from Vancouver, reflecting on his week-long experience in 2015. It renewed my sense of teaching mission at a fundamental bedrock level. By the end of 2018. 925 instructors had been trained to offer Inside-out programming in 45 US states and 12 countries, and about half of these instructors had taught Inside-Out classes. Part of the instructor training was focused on starting new Inside-Out courses, which meant creating university-prison partnerships. By the end of 2018, more than 150 partnerships had been formed between correctional facilities and educational institutions as diverse as Ohio State University and Stanford. One Inside-Out program in Mexico was made up of students who had worked in drug cartels, while another at the University of Sydney focused on incarcerated women. As the programs grew, Think Tanks sprang up organically, and by 2018, the Inside Out Center was coordinating communication between more than 30 of them In all, 35,000 inside and outside students had completed coursework in many disciplines such as criminal justice law, ethics, sociology, literature, and even yoga. THE INSIDE-OUT CENTER As Inside-Out courses spread into new communities, the Inside-Out Center expanded to serve as the formal hub of the international network. In addition to coordinating faculty training and overseeing the network of Think Tanks, the Inside-Out Center handled media coverage, maintained the website, tried to connect with alumni, and promoted the organization's vision and values (see Exhibit 1). Including Pompa, the Inside- Out Center employed two full-time and five part-time staff. The Inside Out Center did not have a board, but relied instead on three committees of Inside-Out instructors and staff to lead key initiatives. The Executive Committee assisted with major decisions, especially at critical decision-making points or as new issues arose. The Network Committee offered direction in building out the teacher trainings and provided ongoing support to the faculty network. The Evaluation and Research Committee assisted groups or individuals who were interested in evaluating the program and also oversaw the ethical considerations that could be raised by research and evaluation efforts. The Think Tanks continued to play a pivotal role in the leadership of the Inside-Out Network. Think Tank members helped plan and conduct training sessions; developed independent projects such as re-entry programs for people who were being released, and led community workshops on racial education, justice, and civic participation Indeed, as civic dialogue became increasingly polarized. Think Tanks began to explore ways to promote dialogue across all kinds of social fault lines. Finally, Think Tanks provided continuity and coherence. Because so many of its members were serving life sentences, the Graterford Think Tank, in particular, provided an umusually stable source of guidance, thought-leadership, and cultural continuity for the Inside-Out Network "The Think Tanks were generated out of a bonded feeling and deep connection," said Tyrone Werts, an Inside-Out veteran who had served 37 years behind bars before joining Pompa as the intemational Think Tank coordinator. Think Tank participants spoke movingly of the importance of the Think Tank's work and took satisfaction in affecting the outside world by learning with and helping to educate outside students, instructors, and community members. The Inside-Out Network was highly decentralized, and all of the funding for specific courses came from participating institutions. Tuition dollars from the outside students funded the instructors' salaries, while partnering correctional facilities provided inside students with classroom space and correctional officers. The Inside Out Center itself was funded primarily through foundation grants, donations from individuals, and eamed revenue from the faculty training sessions. Private funding required long hours of work to obtain and was unpredictable. For example, in 2015, The Inside-Out Center applied to renew a $300.000 grant through the Ford Foundation but was awarded only $100,000, in part because the foundation had changed its remit (see Exhibit 2). HIGHER EDUCATION IN PRISONS As of 2016, 70 per cent of all US high-school graduates were enrolling in (although not necessarily finishing) colleges and universities, and from 2013 through 2018, the higher education industry grew slowly but steadily at 1.8 per cent annually to become a $497.3 billion portion of the $1.5 trillion education industry. Despite that growth, university administrators were increasingly concerned with projected declines in the numbers of high-school graduates, rapidly increasing internal costs, and growing public criticism about the high cost of college tuition." To remain competitive and engage potential new students, universities worked to differentiate their offerings. Online education, volunteer programs, travel abroad experiences, and community engagement programs such as Inside-Out were among the strategies universities employed to help their programs stand out.2 Prison education was a particularly relevant learning opportunity for students in 2018. The Black Lives Matter movement was raising awareness of racial discrimination in the United States, including the disparity in incarceration rates based on race: African Americans were five times more likely than Caucasians to be incarcerated and made up 40 per cent of all people incarcerated in the United States despite representing only 13 per cent of the population - The divisive 2016 presidential election had also drawn attention to the lack of political dialogue about these differences across the country, and pointed to the need for civil discourse between people holding differing views. Indeed, from a smattering of local university programs started in the 1970s (such as Villanova University's, launched in 1972)," prison education had grown into an estimated $62 billion industry. 16 While Inside-Out was unique in its approach it competed with several other innovative programs. The Harvard Organization for Prison Education and Reform and the Petey Greene Program sent trained volunteers to tutor incarcerated individuals with the dual goals of offering prison education and advocating for structural reforms. The Bard Prison Initiative offered college courses and degrees to people incarcerated in six prisons in New York State and boasted a 2 per cent recidivism rate among graduates." In 2015, prison education efforts received a boost when govemment-backed Pell grants were made available in a limited way, to help find education for people in prisonalthough by 2018, the new administration had indicated that it was unlikely to renew the grants. 18 In recent years, technology-based prison educational solutions had also become available. Code 7370 was a non-profit computer programming class in San Quentin, California, that sought to reduce recidivism by helping people in prison prepare for jobs in technology and business following their release. Because students had limited access to technology, they completed assignments without Internet access by using special desktop computers with double-monitor configurations that allowed them to receive instruction from remote teachers through an administrator's computer. 19 American Prison Data Systems Innertainment Delivery Systems, and Edovo (Education Over Obstacles) made customized, tamper-proof tablets equipped with educational materials available to people in prison for about $2 per hour." JPay, another competitor, provided in prison video educational and gaming content, and an e-messaging service to help people in prison connect to families "to empower those individuals with access to educational tools and assist in their overall rehabilitation process. "21 JPay offered jails and prisons approximately $0.05 for every message between people in prison and their families, a lucrative extra revenue source for participating facilities. EDUCATION'S EFFECT ON PEOPLE IN PRISON Education played a complex role within prisons. Prisons around the country faced mumerous issues, including overcrowding understaffing, high tumover rates among officers, and low funding for employee training and operations. Poor conditions had the potential to increase tensions between prison staff and those incarcerated which could contribute to violence. One review of incidents in Maryland prisons documented $860,000 of medical care required as a result of 257 assaults, not including the costs associated with five deaths (two officers and three incarcerated individuals), lost work time for officers injured, and extra legal costs. These realities made attractive any program that could decrease violent incidents in prisons. Prisons also struggled with budget shortfalls. Indeed, many prisons had begun to bill prisoners for essentials such as meals, toilet paper, clothing, and dental care, a practice commonly referred to as pay-for-stay." Why should the people of Elko County pay for somebody else's meals in jail?" asked one commissioner in Elko County, Nevada, where a pay-for-stay program had been implemented. ** Others saw these programs as part of the punishment. "If they are violating the law," said one sheriff in Iowa, "then they should be the ones to pay for it." Officials in Riverside County, California, voted to approve a plan to charge people in prison for their stay and reimburse the county for food, clothing and health care, stating. "You do the crime, you will serve the time, and now you will also pay the dime." National studies had demonstrated that prison education led to multiple positive outcomes for incarcerated individuals and for society at large. Completing college courses while in prison improved self-esteem and social competence, both during incarceration and following release. It also reduced the experience of violence while inside prison (by about 9 per cent, according to one study). Further, a careful assessment of 58 studies suggested that any exposure to education while in prison (whether at the high-school or college level, and whether or not completed) resulted in a three-year recidivism rate of between 30.1 per cent and 38.6 per cent, compared with between 43.3 per cent and 51.8 per cent for those receiving no education while in prison. Estimates of the cost to society of crimes committed varied widely, from $2,100 per incident for theft to $87,000 for assault to $8,650,000 for murder. Other estimates suggested that, over a full career, men with bachelor's degrees averaged $660,000 more in median lifetime earnings than did high- school graduates, and for women it was $450,000 more. For both men and women with some college education, the differential was $170,000.29 FUNDING CHALLENGES Despite the steady growth of the Inside-Out Network and the passion of the students and instructors involved, Pompa worried about the Inside-Out Center's sustainability. As costs rose, universities worried about class size, and Inside-Out classes typically had no more than 15 paying outside) students to cover the cost of faculty timefrom $10,000 to more than $25,000 per course. Prison wardens had more education offerings, including technology platforms, from which to choose. With the politicization of all discussions concerning prisons and race there was an increased need to engage in public relations on behalf of the Inside-Out Center's dialogue-based approach Even Inside-Out's growth had created challenges, as the already busy staff computers systems, and travel budgets were stretched almost to the breaking point as they struggled to accommodate the increases in instructors to be trained, partners to be managed, Think Tanks to be coordinated, and alumni to be engaged. Worst of all, finding was becoming ever more fickle. The partnership with Temple University had provided core support over the years, including access to office space and partial funding of Pompa's salary, but the level of support varied with leadership changes and budgetary constraints, and centres, including Inside-Out, were being increasingly pressured to generate additional funds. Grants and donations were becoming harder to obtain and renew, putting more pressure on eamed income from training programs to cover expenses. Over the years, the Inside-Out Center had secured a few large grants, but each lasted for only a limited time, often because the foundation priorities changed. Complicating matters, foundations and even individual donors) increasingly asked for rigorous, often quantitative, measures of impact. In a 2017 suvey, 98 per cent of funders said that impact was among their top three considerations when awarding grants, while 88 per cent of respondents said they prioritized program outcomes in their review of non-profit reports:31 Finally, the Inside-Out Center struggled to secure the resources and staff required to track down and engage its alumni basea task made all the more difficult by the realities that the alumni were young and/or incarcerated, and that they identified with local Inside-Out programs rather than with the intemational Inside-Out Network MEASURING INSIDE-OUT'S IMPACT Measuring the impact on inside students was a delicate proposition. The Inside-Out program prided itself on treating people in prison as people, in contrast to the correctional system which literally referred to incarcerated individuals by their inmate numbers. Historically, people in prison had been used in studies without their consent, which reinforced the need for the Inside-Out Center to be clear about its methods and goals if it did choose to begin collecting data. Federal regulations and university practices seriously restricted the study of vulnerable populations," including people in prison. The Inside-Out Center also shied away from measuring recidivism citing the intense pressure people faced upon their release. I'm not under the illusion that this is a silver bullet," Pompa said. "When somebody gets out of prison, there are so many variables hitting them. There is no way that a 15-week class is able to stand up against those variables. Measuring the impact on outside students was similarly challenging, as the Inside-Out courses were but one part of the college experience. And measuring the impact of the Inside-Out Network was harder still with its alumni dispersed across a dozen countries and multiple prison systems. Reflecting these realities, many staff and Think Tank members argued passionately that the power of Inside- Out was in the transformation of individual participants, both inside and outside and so was best captured in stories, not numbers. Further, some suggested that trying to capture the experience in numbers might detract from Inside-Out's mission and culture. When reporting program results, Inside-Out had long focused on stories. Students completing surveys at the end of each course regularly reported that the course had changed their lives, affected their majors and career choices, and impacted their perspectives on criminal justice and themselves. Informally, several correctional institutions and Think Tanks had reported improved behaviour and increased leadership intemally following Inside-Out courses, but there were no systematic records. Further, while these stories were inspiring, they captured only short-term impacts. Several times, Pompa and her team had attempted to follow up with instructors to leam what impacts they had noticed related to their classes. "We really wanted to put a finger on the lasting impact," Krueger said, "to see what [the experience] means five years from now." Unfortunately, these attempts to collect impact data were limited due to lack of resources and staff time. Finally, questions of ownership and impact emerged from the questions about measurement. Who were the mumbers for, and how could Inside-Out maintain control over, access to, and the use and interpretation of the measures? Would finders interpret the measures the same way that Inside-Out did? Would prison officials or govemments or competitor programs gain access to the measures? In the highly controlled world of prisons, a world in which even small events or missteps could be amplified, Inside-Out had been extremely careful to preserve its standards and control its story. Would an attempt to quantify impact in any way distort or distract from the Inside-Out experiences and effects that the measurement was meant to convey? NEXT STEPS As Pompa prepared for 2019, with 10 training sessions scheduled in several countries, a number of new Think Tanks emerging, and efforts to connect with alumni expanding, she knew something needed to change. The past 21 years had proven that Inside-Out worked that students, prisons, and communities benefited from Inside-Out's unique approach to leaming. Yet Pompa also knew that the Inside-Out Center desperately needed to secure a steady stream of funding to support the Inside Out Network in an increasingly competitive prison education and funding context. Both to raise Inside-Out's profile and to secure additional resources, the Inside-Out Center needed to find a cost-effective, and culturally appropriate way to measure and communicate its impact to its many stakeholders. The question washow? EXHIBIT 1: INSIDE-OUT MISSION AND VISION STATEMENTS The Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program Social Change through Transformative Education Mission Statement Education in which we are able to encounter each other, especially across profound social barriers, is transformative and allows problems to be approached in new and different ways. Inside-Out's mission is to create opportunities for people inside and outside of prison to have transformative leaming experiences that emphasize collaboration and dialogue and that invite them to take leadership in addressing crime, justice, and other issues of social concern. Vision Statement We believe that, by studying together and working on issues of crime, justice, and related social concerns, those of us inside and outside of prison can catalyze the kinds of changes that will make our communities more inclusive, just, humane, and socially sustainable. Source: Company documents: The Inside-Out Center, Mission." accessed December 29. 2018. www.insideoutcenter.org/mission-inside-out.html. EXHIBIT 2: THE INSIDE-OUT CENTER FINANCIALS, 2015/162018/19 The Inside-Out Center Cash Flows (US$, 000s) FY15-16 FY16-17 FY17-18 FY18-19 Cash inflows (projected) Carryover (from previous years) 90 428 333 179 Trainings 185 251 255 323 Grants 125 185 59 60 Gifts 427 70 40 37 Subtotal 827 934 687 599 Cash outflows Staff 150 357 432 294 Trainings 79 90 95 106 Office 23 43 30 33 Indirect 10 18 9 12 Subtotal 262 508 566 445 Inflows less outflows 565 426 121 154 Note: 'The carryover varies from the previous year's "Inflows-less-outflows because of the university's allocation of overheads, carry-over rules, and cash recognition policies. Source: Calculated from company documents. 1. What is the Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program? How different is it from other prison education initiatives? How similar is it to other prison education initiatives? What does the Inside-Out Center do? 2. Who are the stakeholders of the Inside Out Prison Exchange Program? Describe the interest of each stakeholder. 3. What would be the theory of change of the Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program? Start by evaluating the mission and vision of Inside-Out. 4. Create the logic model for the Inside-Out's inside students. 5. How would you measure and communicate the impacts of Inside-out? What would be the challenges in measuring and communicating these impactsStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts