Question: Comment your email address please so I can send you chapter16. Thank you How do firms make investment decisions? In our first pass at the

Comment your email address please so I can send you chapter16. Thank you

Comment your email address please so I can send you chapter16. Thank you

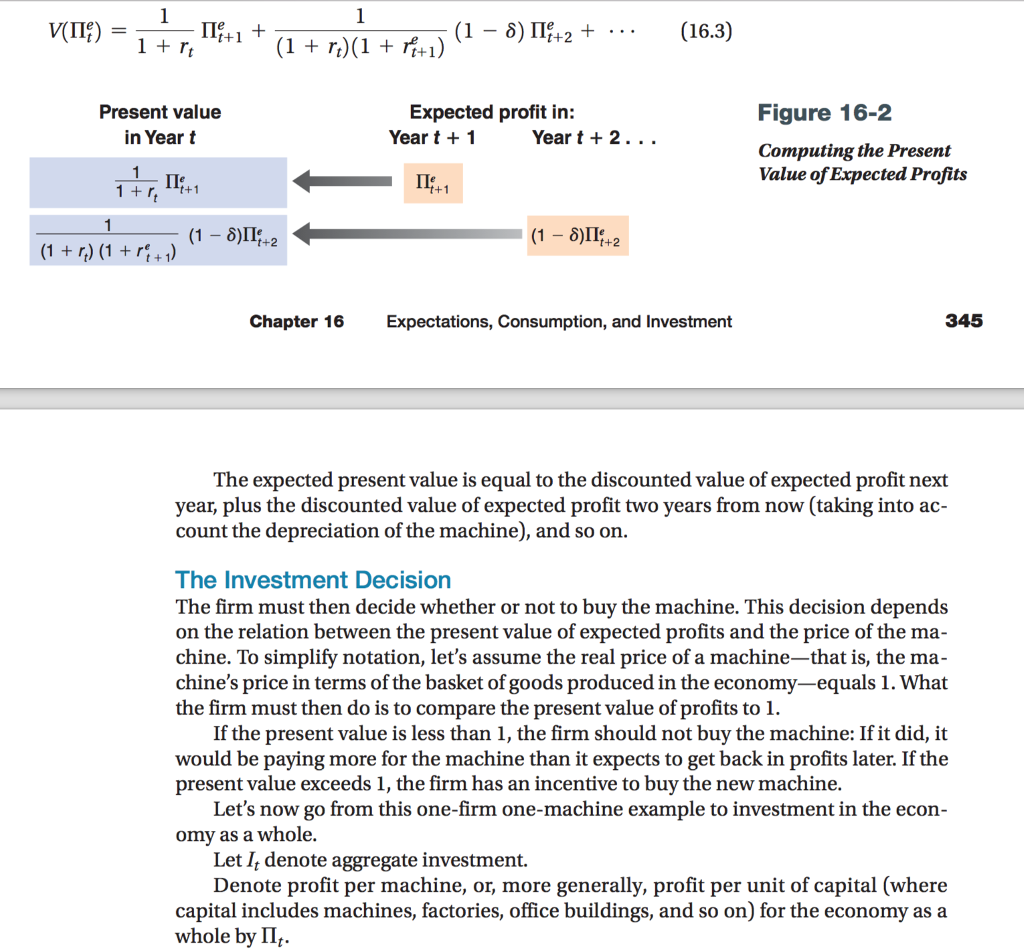

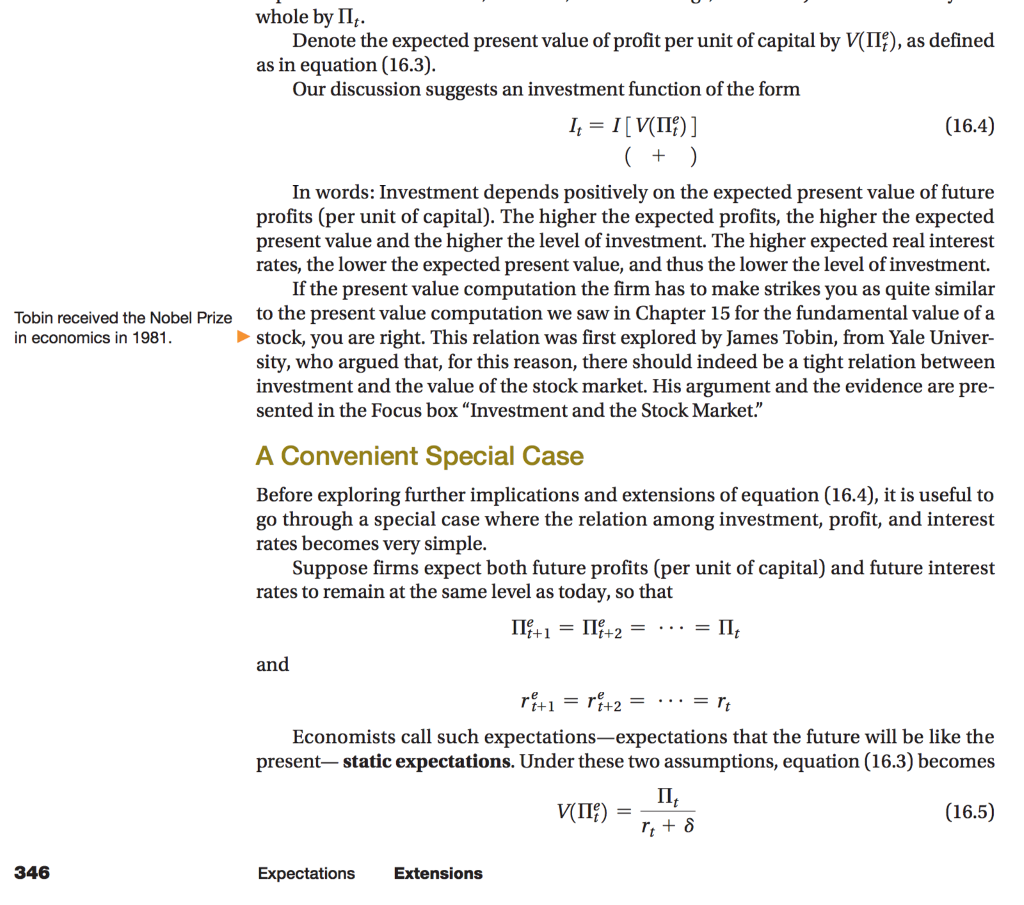

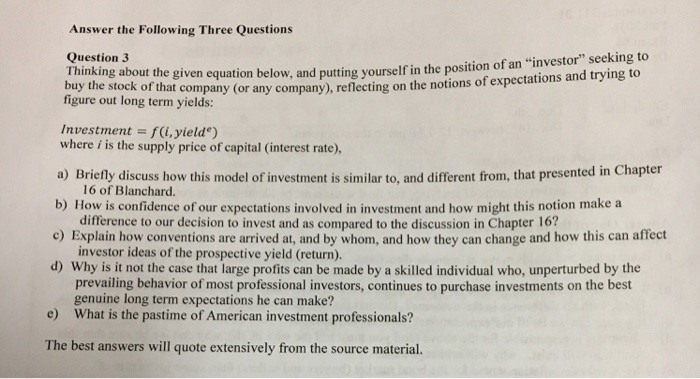

How do firms make investment decisions? In our first pass at the answer in the core (Chapter 5), we took investment to depend on the current interest rate and the current level of sales. We refined that answer in Chapter 14 by pointing out that what mattered was the real interest rate, not the nominal interest rate. It should now be clear that investment decisions, just as consumption decisions, depend on more than current sales and the current real interest rate. They also depend very much on expectations of the future. We now explore how those expectations affect investment decisions. Just like the basic theory of consumption, the basic theory of investment is straightforward. A firm deciding whether to invest-say, whether to buy a new machine-must make a simple comparison. The firm must first compute the present value of profits it can expect from having this additional machine. It must then compare the present value of profits to the cost of buying the machine. If the present value exceeds the cost, the firm should buy the machine-invest; if the present value is less than the cost, then the firm should not buy the machine-not invest. This, in a nutshell, is the theory of investment. Let's look at it in more detail. Let's go through the steps a firm must take to determine whether to buy a new machine. (Although we refer to a machine, the same reasoning applies to the other components of investment-the building of a new factory, the renovation of an office complex, and so on.) To compute the present value of expected profits, the firm must first estimate how long the machine will last. Most machines are like cars. They can last nearly forever; but Look at cars in Cuba. as time passes they become more and more expensive to maintain and less and less as time passes they become more and more expensive to maintain and less and less reliable. Assume a machine loses its usefulness at rate delta (the Greek lowercase letter delta) per year. A machine that is new this year is worth only (1 - delta) machines next year, (1 - delta)^2 machines in two years, and so on. The depreciation rate, delta, measures how much usefulness the machine loses from one year to the next. What are reasonable values for 5? This is a question that the statisticians in charge of measuring the U.S. capital stock have had to answer. Based on their studies of depreciation of specific machines and buildings, they use numbers between 4% and 15% for machines, and between 2% and 4% for buildings and factories. The firm must then compute the present value of expected profits. To capture the fact that it takes some time to put machines in place (and even more time to build a factory or an office building), let's assume that a machine bought in year t becomes operational-and starts depreciating-only one year later, in year t + 1. Denote profit per machine in real terms by Product. If the firm buys a machine in year t, the machine will generate its first profit in year t + 1; denote this expected profit by Product_t + 1^e. The present value, in year t, of this expected profit in year t + 1, is given by If the firm has a large number of machines, we can think of delta as the proportion of machines that die every year (think of lightbulbs-which work perfectly until they die). If the firm starts the year with K working machines and does not buy new ones, it will have only K(1 - delta) machines left one year later, and so on. This is an uppercase Greek pi as opposed to the lowercase Greek pi, which we use to denote inflation. This term is represented by the arrow pointing left in the upper line of Figure 16-2. Because we are measuring profit in real terms, we are using real interest rates to discount future profits. This is one of the lessons we learned in Chapter 14. Denote expected profit per machine in year t + 2 by Product_t + 2^e. Because of depreciation, only(1 - delta) of the machine is left in year t + 2, so the expected profit from the machine is equal to (1 - delta) Product_t + 2^e. The present value of this expected profit as of year t is equal to 1/(1 + r_t)(1 + r_t + 1^e) (1 - delta) Product_t + 2^e This computation is represented by the arrow pointing left in the lower line of Figure 16-2. The same reasoning applies to expected profits in the following years. Putting the pieces together gives us the present value of expected profits from buying the machine in year t, which we shall call V(Product_t^2): V(Product_t^e) = 1/1 + r_t + 1/(1 + r_t)(1 + r_t + 1^e) (1 - delta) Product_t + 2^e + ... The expected present value is equal to the discounted value of expected profit next year, plus the discounted value of expected profit two years from now (taking into account the depreciation of the machine), and so on. The firm must then decide whether or not to buy the machine. This decision depends on the relation between the present value of expected profits and the price of the machine. To simplify notation, let's assume the real price of a machine-that is, the machine's price in terms of the basket of goods produced in the economy-equals 1. What the firm must then do is to compare the present value of profits to 1. If the present value is less than 1, the firm should not buy the machine: If it did, it would be paying more for the machine than it expects to get back in profits later. If the present value exceeds 1, the firm has an incentive to buy the new machine. Let's now go from this one-firm one-machine example to investment in the economy as a whole. Let I_t denote aggregate investment. Denote profit per machine, or, more generally, profit per unit of capital (where capital includes machines, factories, office buildings, and so on) for the economy as a whole by Product_t. whole by Product_t. Denote the expected present value of profit per unit of capital by V(Product_t^e), as defined as in equation (16.3). Our discussion suggests an investment function of the form I_t = I[V(Product_t^e)] (+) In words: Investment depends positively on the expected present value of future profits (per unit of capital). The higher the expected profits, the higher the expected present value and the higher the level of investment. The higher expected real interest rates, the lower the expected present value, and thus the lower the level of investment. If the present value computation the firm has to make strikes you as quite similar Tobin received the Nobel Prize t0 the present value computation we saw in Chapter 15 for the fundamental value of a in economics in 1981. stock, you are right. This relation was first explored by James Tobin, from Yale University, who argued that, for this reason, there should indeed be a tight relation between investment and the value of the stock market. His argument and the evidence are presented in the Focus box "Investment and the Stock Market." A Convenient Special Case Before exploring further implications and extensions of equation (16.4), it is useful to go through a special case where the relation among investment, profit, and interest rates becomes very simple. Suppose firms expect both future profits (per unit of capital) and future interest rates to remain at the same level as today, so that Product_t + 1^e = Product_t + 2^e = ... = Product_t and r_t + 1^e = r_t + 2^e = ... = r_t Economists call such expectations-expectations that the future will be like the present- static expectations. Under these two assumptions, equation (16.3) becomes V(Product_t^e) = Product_t/r_t + delta Thinking about the given equation below, and putting yourself in the position of an "investor" seeking to buy the stock of that company (or any company), reflecting on the notions of expectations and trying to figure out long term yields: Investment = f (i, yield^e) where i is the supply price of capital (interest rate), a) Briefly discuss how this model of investment is similar to, and different from, that presented in Chapter 16 of Blanchard. b) How is confidence of our expectations involved in investment and how might this notion make a difference to our decision to invest and as compared to the discussion in Chapter 16? c) Explain how conventions are arrived at, and by whom, and how they can change and how this can affect investor ideas of the prospective yield (return). d) Why is it not the case that large profits can be made by a skilled individual who, unperturbed by the prevailing behavior of most professional investors, continues to purchase investments on the best genuine long term expectations he can make? c) What is the pastime of American investment professionals? The best answers will quote extensively from the source material

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts