Question: Describe how learning happens. How do you know it is happening or when you have learned something? What is the role of assessment for how

Describe how learning happens.

How do you know it is happening or when you have learned something?

What is the role of assessment for how you think learning happens?

\

\

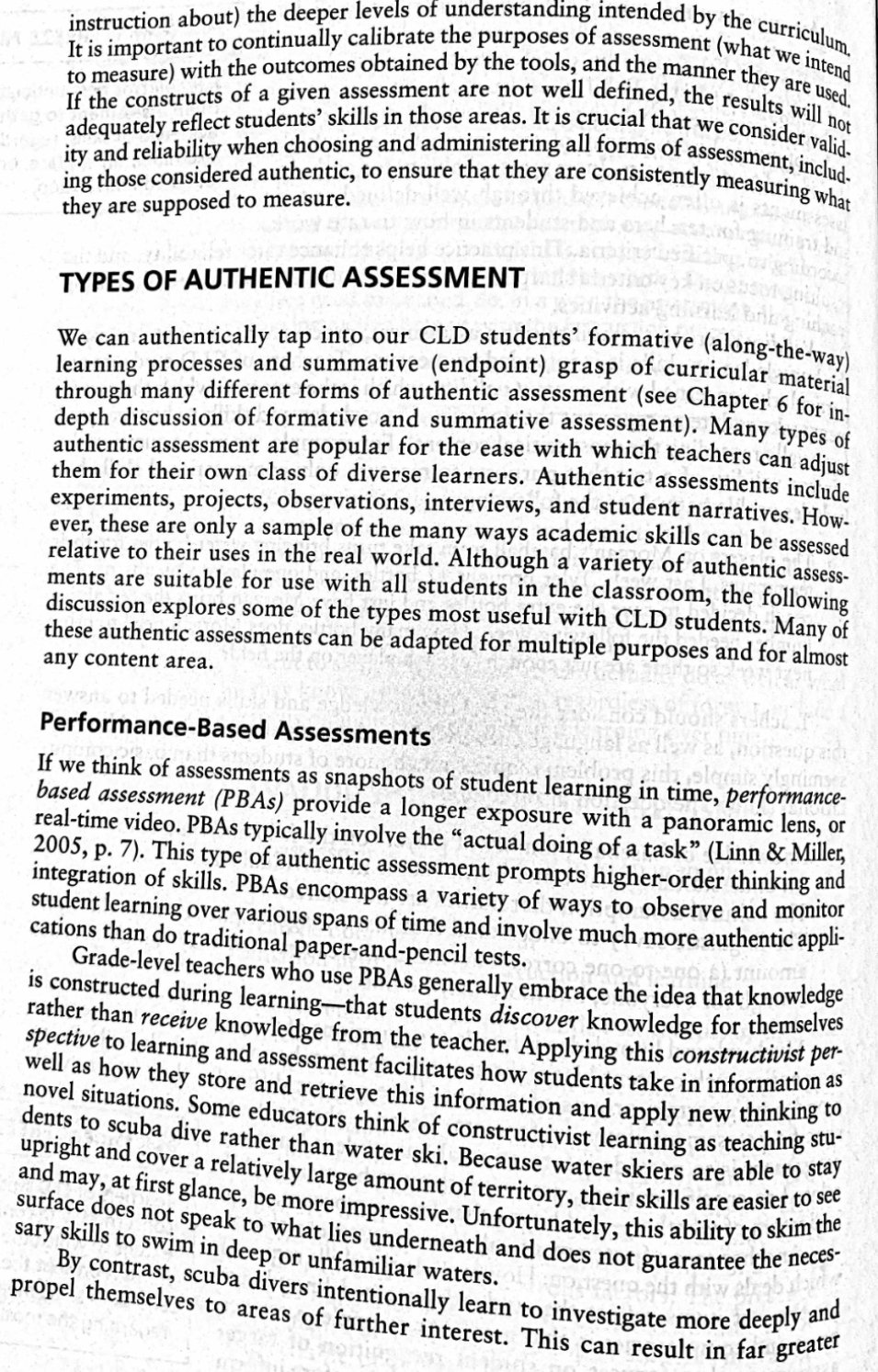

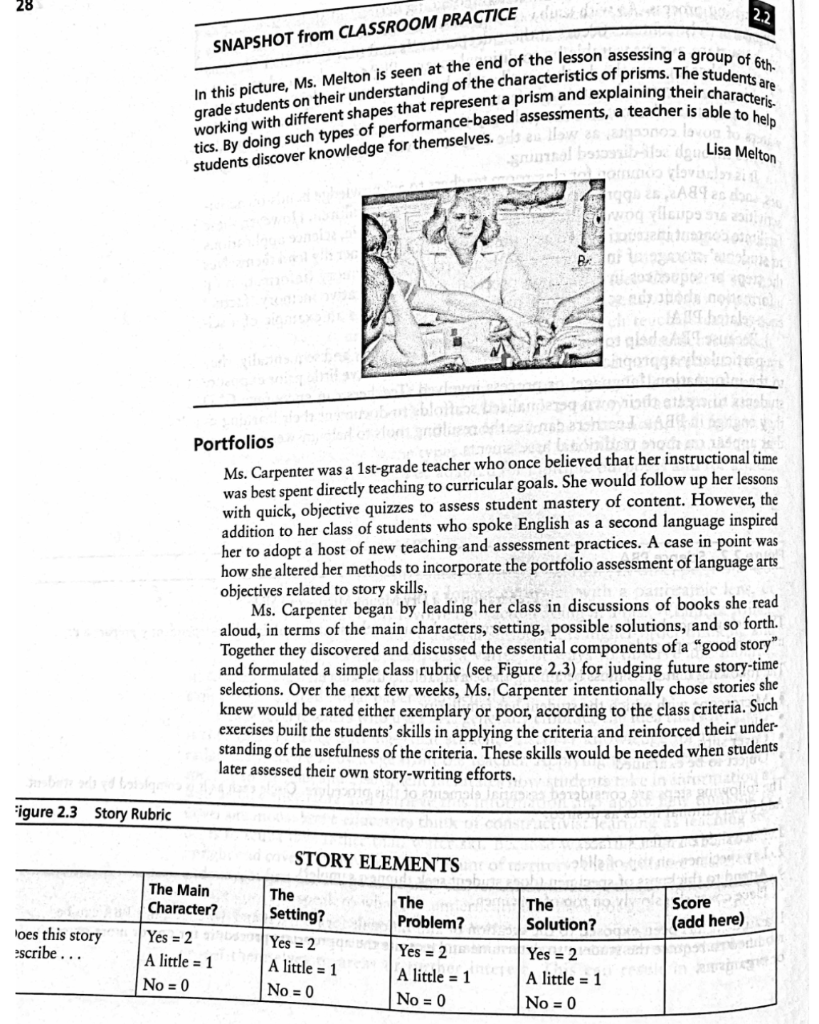

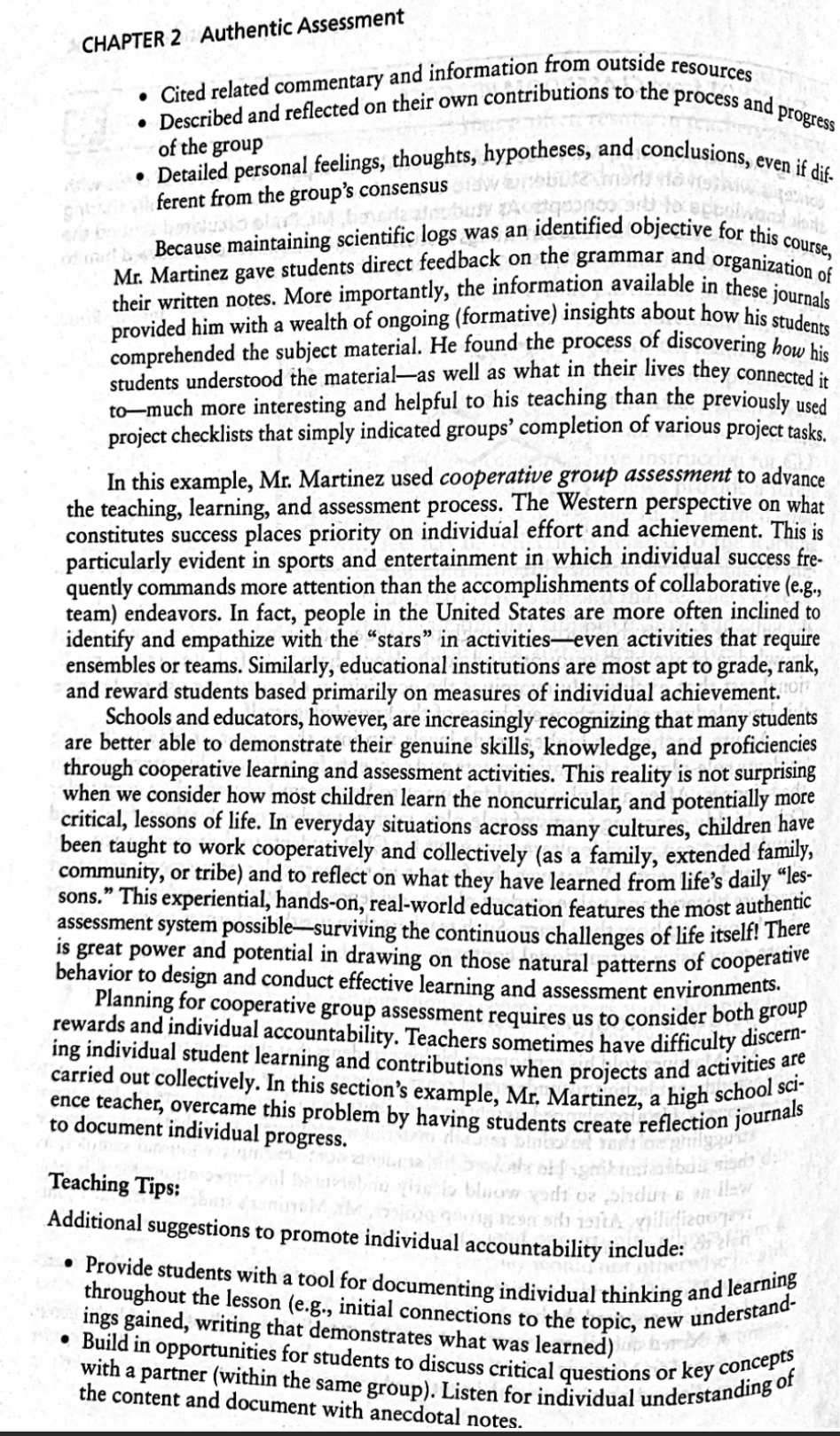

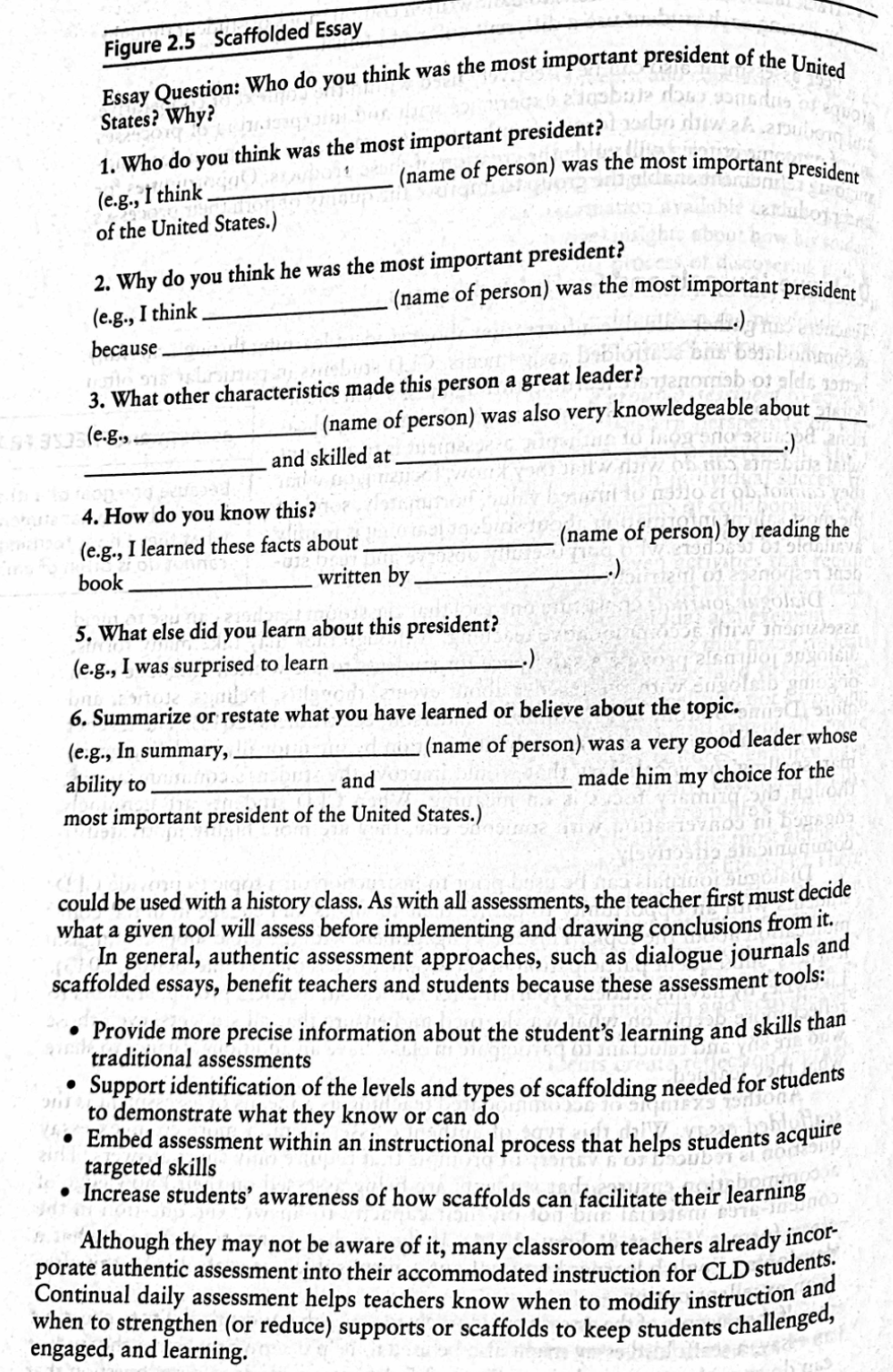

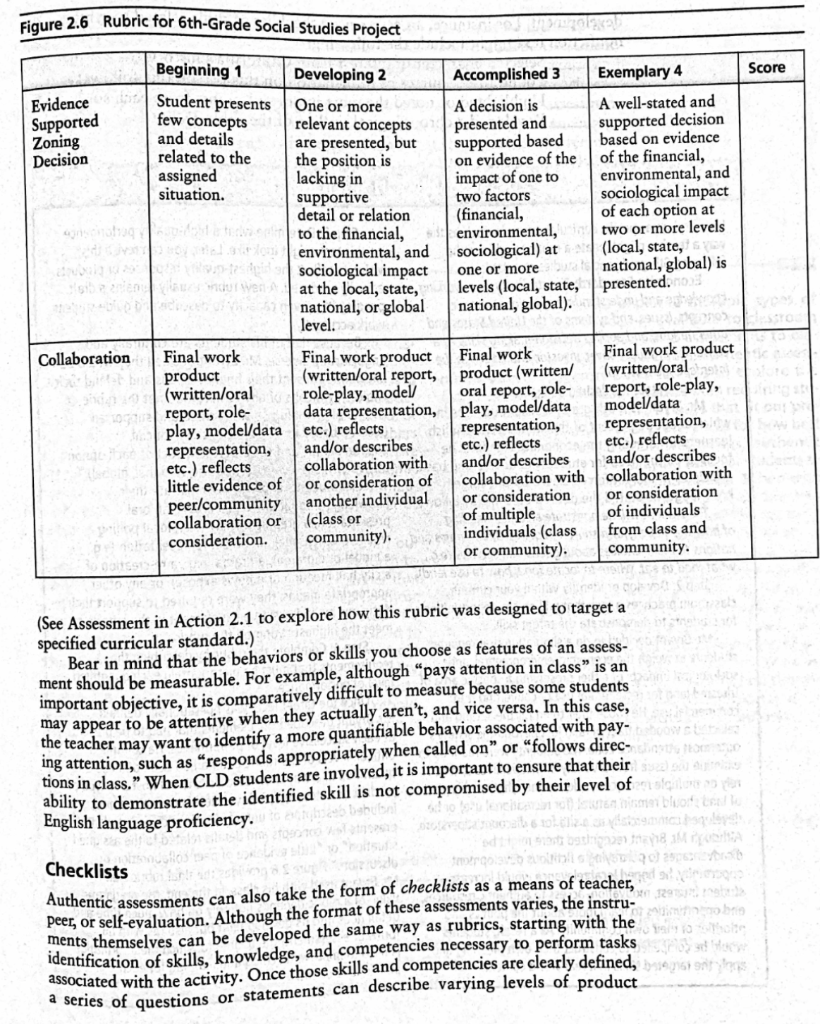

A more expansive view of what learning looks like can help us create good schools for today's students and today's society. By Maxine McKinney de Royston, Carol Lee, Na'ilah Suad Nasir, \& Roy Pea Consider the kinds of learning possible at the Chche together with young people in community math and Konnen Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which notonly science workshops, as well as activities and celebrations teaches a rich curriculum in the sciences, humanities, and that reaffirm students' identities, culture, and accomplishother fields, but also invites students to draw upon their own ments (e.g., talks, poetry readings, musical performances). linguistic repertoires to help them make sense of academic This focus on learning as involving support, engagement, material, while inviting them to analyze their own and each and culturally relevant spaces for families is mirrored other's differing ways of using language (Warren \& Rosebery, in the professional development for AAMA teachers, in 2004). which their identities as Black male teachers are explored For instance, in one study of teaching and learning at and affirmed, their identities and expertise as educators Chche Konnen, researchers observe a Black 2nd-grade are supported, and they have regular opportunities to boy's obvious sense of comfort, during a science lesson, in wrestle with classroom tensions and challenges together. using a kind of metaphoric reasoning - a common practice Research has shown that the AAMA approach has been within Black discourse communities in the U.S. to help highly effective in supporting the retention and perforhim make sense of the life cycle of a pumpkin: He thinks mance of students (Dee \& Penner, 2019). of the pumpkin as a spider, he explains, "because when the momdiesitlayseggsbeforeitdies"(Nasiretal.,2006,p.498).Theboyandhisclassmatesgoontodiscusshowthemetaphorillustratesthewayapumpkincreatesseedsbeforeitdecays(e.g.,likethespider,itcreatesnewlifeasithangsonthebrinkofdeath),aswellasdiscussinghowpumpkinseedsandspidereggsdiffer.Inshort,thisschoolhascreatedanenvironment,curriculum,andteachingmodelthatasksstudentsnottoleavetheirculturalidentitiesathomebuttousetheirdiverselinguisticpracticesasresources,bothintheclassroomandthroughouttheirlives.Social-emotionaldevelopmentingoodschoolsIftheyweretoadoptaholisticviewoflearning,schoolswouldalsoplacemuchgreateremphasisonsocial-emotionaldevelopment,treatingitasacorepartofthecurriculum,notasanadd-ontoacademicinstructionorasaspecialprogrammeantonlyforchildrenexperiencingadversechildhoodexperiences.Whereasacademiclearninghastraditionallybeenviewedasapurelycognitiveprocess(orperhapsasachainofstimuliandresponses)bywhichindividualsacquireknowledgeandskills,theRISEprinciplesbuild Teachers in good schools Relatedly, if we took seriously a robust science of learning, we would view teaching not as a set of scripted "best practices" and instrumentalist approaches, but as a work that is both principled (based on specific methods) and improvisational, requiring them to know how to adapt their instruction to the students before them. This would require us to respect teachers as human development professionals (i.e., profes- sionals tasked with cultivating human life and society) who must be provided with the support, materials, and com- pensation needed to prepare for and engage in this complicated and intellec- tually challenging work. And to support their instructional efforts, we would bring parents, caregivers, families, and community members on as team members with educators, establishing invaluable home-school connections. For instance, we see such prac- tices at the African American Male Achievement (AAMA) Initiative in the Oakland Unified School District (Nasir, Givens, \& Chatmon, 2018), where families and caregivers learn have distilled this new science of learning into the RISE principles: Learning is rooted in our biology and in our brains and inseparable from our social and cultural experiences; integrated with developmental processes that involve the whole person; shaped through culturally organized activities of everyday life, and experienced as physical and social interactions. Schools that take these principles into account will honor diverse cultural repertoires, partner with families and communities, and promote deep engagement with the disciplines, with one's identities and communities, and with equitable social change. This is the vision of good schooling that is needed today and into the future. It is important to have authentic assessment when assessing ESL [CLD] students. Authentic assessment allows teachers to be able to look at the results and know that they truly represent where the students are, at that time. We all know that assessments can often offer different struggles when it comes to ESL [CLD] students. Often students can struggle on some assessments just because of the way the question is asked. Authentic assessments allow teachers to not test the students over language, but test them over content to make it an accurate assessment. Teachers can use authentic assessment in a variety of ways to benefit future learning in the classroom. Rick Malone, High School Mathematics Teacher One of the primary purposes of this text is to explore the range of ways for gathering and interpreting information about culturally and linguistically diverse (CLD) student learning to inform instruction. For years, standardized and teacher-made tests (e.g., multiple choice, fill-in-the-blank) have dominated our views and practices about measuring student learning. These tests typically require memorization and do little to encourage students' independent thinking. The assessments fail to demonstrate whether or not the students are able to process the new information to produce clear understanding of the material covered. The results of such assessments have not always yielded information useful to classroom teachers for creating instructional accommodations for CLD students. Although the data generated by traditional tests are certainly helpful in comparing students, programs, and schools on quantitative bases, what the data actually mean for each individual student is often much more obscure and tells us little about language and academic growth. VOICES from the EIELD 2,1 When teachers use observations as forms of assessments and allow students to bring their own schema to each vocabulary word, it helps teachers identify any misconceptions that may need to be addressed during instruction. When the teacher continues to observe and question as the students work in groups to show connections between the words, the assessment process becomes part of the instruction. This allows us as teachers to consider the following: Are the students able to read the words correctly? Are their connections making sense? Are all students participating? If a student is not participating, why? visuals or manipulatives need to be used. So, in a way, the assessments that RELIABILITY AND VALIDITY OF AUTHENTIC ASSESSMENTS When creating authentic assessments, it is important to keep in mind: - Why they are used - What information can be obtained from them - How can this information help improve instruction and learning As with other forms of measurement, we judge authentic assessments by their reliability and validity as indicators of student learning. Reliability is best understood as the power of an assessment to gather consistent evidence of skills, regardless of the examiner, time, place, or other variables related to its administration. Reliable tests are also those that prove sensitive to measuring the incremental changes that reflect growth and improvement in the areas being assessed (Stiggins \& Chappuis, 2017). This is a critical feature when assessments are used to inform instruction rather than merely provide baseline or end-term indices of achievement. The reliability of an assessment can be compromised or threatened by numerous factors. The presence of distracters (internal such as hunger and anxiety, or external such as ambient noise) can affect the performance of a student or group of students in ways that render those results less reliable or representative than if the assessment had occurred under different conditions. assessments is often achieved through well-defined criteria and training for teachers and stiade specified criteria. This practice helps enhance rater the resulting focus on key criteria sharpens the teacher's attention to those skills during teaching and learning activities. Validity refers to the ability of an assessment, process, or product to measure the knowledge or skills it is intended to measure. Teachers of CLD students are particularly concerned with content validity, which is the extent to which the assessment tasks and items represent the domain of knowledge and skills to be measured (especially regarding the most critical content). For example, we might question the content validity of a test that purports to measure only computational skills but includes problems such as the following: The players on Morgan's baseball team take turns bringing water bottles for their teammates. Last week, Tyler brought 12 bottles, and one player was absent. The coach decided to save the extra bottles and just have Morgan bring the remaining number needed the following week. How many bottles does Morgan need to bring next week so there are just enough for each player on the field? Teachers should consider the level of knowledge and skills needed to answer this question, as well as language cues a CLD student might misinterpret. Although seemingly simple, this problem requires much more of students than basic computational skills. The question also requires: - Knowledge of baseball (number of players on the field and on a team) - An understanding that water bottles come in individual sizes - The cultural assumption that bottles are not shared - The linguistic savvy to understand that just enough implies exactly the right amount (a one-to-one correspondence), whereas enough may signify at least enough for everyone, but more may be fine Much cultural knowledge is implicit in questions of this sort. An astute teacher may notice such content bias right away or, as often happens, only later begin to wonder why certain groups of students have greater difficulty than others with specific assessment items or formats. Because the goal of assessment is to provide information about student learning related to specific content, assessments must be meaningful indicators of whether-and how-that learning occurs. Another area of assessment validity is construct validity, knowledge at ever-deeper levels, as well as an ongoing desire and ability to continue the learning process. As with scuba diving, much of the learning that takes place in constructivist contexts occurs at these deeper levels and may be neither obvious on the surface nor measurable by traditional means. PBAs are designed to create situations that tap into the depth as well as the breadth of student learning. Instead of asking students to reiterate static facts or volumes of superficial content, PBAs allow students to demonstrate how deeply they understand and can navigate the waters of novel concepts, as well as the degree to which they can make new discoveries through self-directed learning. It is relatively common for classroom teachers to acknowledge hands-on activities, such as PBAs, as appropriate and beneficial for young children. However, these activities are equally powerful for older students. For example, science applications facilitate content instruction and assessment because they generally lend themselves to students' storage of information both as procedural memory (information on the steps or sequences involved in a process) and as declarative memory (factual information about the science content). Figure 2.2 provides an example of a science-related PBA. Because PBAs help to scaffold student learning naturally and sequentially, they are particularly appropriate for CLD students, who may have little prior exposure to the information, language, or process involved. Teachers can encourage CLD students to create their own personalized scaffolds to document their learning as they engage in PBAs. Learners can use the resulting tools to help answer questions that appear on more traditional assessments. Figure 2.2 Science PBA Preparation of a Dry Mount Microscope Slide This performance-based assessment is designed to document the student's ability to independently prepare a dry mount microscope slide. The following materials must be among those available to the student: - Microscope with which the student has familiarity - Slides. - Cover slips - Object to be examined The following steps are considered essential elements of this procedure. Circle each as it is completed by the stude Add observational notes as desired. 1. Place slide on a flat surface. 2. Lay specimen on top of slide. 3. Attend to thickness of specimen (does student seek thinnest sample?). 4. Place cover slip slowly on top of specimen. If a student has been exposed to the creation of and rationale for both wet and dry slides, this PBA can be modified to require the student to determine and execute the appropriate procedure for one or more objects or organisms. In this picture, Ms. Melton is seen at the end of the lesson assessing a group of 6 th. grade students on their understanding of the characteristics of prisms. The students are working with different shapes that represent a prism and explaining their characteris. tics. By doing such types of performance-basec Lisa Melton CHAPTER 2 Authentic Assessment Carpenter noticed how the stories that evolved from this activity were more personal and animated than those elicited by her typical story starters. The students were eager to share these new stories with peers. When the drawings were finished, they were laminated and added to each student's portfolio. Throughout the year, students had other opportunities to practice and build nasrative skills, such as reporting the news (e.g., family, community, world) and retelling events or stories from different perspectives (e.g., the perspective of one of their favorite action figures). As the year progressed and Ms. Carpenter conferenced with students about their portfolio entries, she was amazed at how often students commented that their earlier stories could have been better. Some students even contrasted them to more recent selections. For instance, Magda said, "That story didn't have a very good ending. This one has a better problem and solution. I tell you more about my characters now, too." By the end of the year, Ms. Carpenter felt that she, her students, and their parents had a much better grasp of student progress than they ever could have gained through traditional indicators of achievement. Portfolio in various forms have been in use for some time. However, early versions often amounted to undifferentiated compilations of student work, sometimes judged merely by overall heftiness or mass. Although portfolios were appreciated as indicators of student (and teacher) effort, many parents felt that this abundance of academic memorabilia provided little information about the actual progress of their children in school. Following are tips for moving away from simply collecting student work and toward a systematic collection of documents/ artifacts that exemplify socioemotional, linguistic, and academic growth. Teaching Tips: - Create an oral language rubric for informal observation of language production three times a year. - Create a checklist to document the learner's ability to take risks when working in groups. - Gather writing samples for each grading period. - Video the student two or three times each grading period sharing information orally (Simple computer applications for recording speech samples enable creation of powerful audio portfolios of students' developing oral or narrative skills.) These are but a few suggestions for systematically collecting informal and authentic artifacts produced by the learner that move assessment to a new level. Portfolios also can include: - Samples of student work that illustrate either mastery or progress - The sequential planning, process reflections, and product outcomes of a project - Some indication of how the student rated him-or herself on the samples, processes, or products included - Student justification and insight regarding the work included The criteria for judging portfolio pieces should reflect outcomes that align with curricular standards. In many cases, school districts align these standards with relevant state and/or national benchmarks. Portfolio assessments are beneficial for CLD students because they offer learners the opportunity to share in their own words what they have gained. Portfolios provide a safe space for students to communicate with the teacher and showcase their work. The tangible proof that they are learning, growing, and contributing is especially motivating for CLD students. Having students create a portfolio sends the message not only that their ideas and thoughts matter, but that regardless of their language proficiency, they can demonstrate their knowledge. The final portfolio serves as a treasure trove of artifacts students can look back on and be proud of. E-portfolios offer the distinct advantage of increasing accessibility of the portfolio with peers, parents, and other educators. With such access comes opportunities for individuals who are influential to the student to provide additional feedback. The exchange of ideas made possible through electronic sharing can benefit students and the larger learning community. E-portfolios have been shown to positively affect students' literacy and metacognition (Nicolaidou, 2013). In summary, portfolio assessments have the power to authentically connect classroom instruction and the assessment of its impact on students. They are alternative assessments in the sense that: - They incorporate both teacher and student perspectives on learning and the assessment of learning. - They offer a longitudinal perspective on academic and language development. - They measure incremental gains in knowledge, skills, and proficiencies. Portfolio assessments are authentic assessments in that: - They derive directly from classroom activities. - They effectively assess student performance. - They reflect in-process adaptations to instructional methods and assessment. - They assess learning in a way that is relevant to and motivating for the student. Self-Assessment and Peer Assessment Student self-assessment can be an extremely valuable tool for learning as well as measurement. When CLD students are engaged in assessing their own work, they more thoroughly and purposefully understand the criteria for high-quality products and performance-and experience greater motivation for meeting those criteria (Sajedi, 2014). Rather than simply attempting to produce work that will satisfy the teacher, students involved in effective self-assessment work toward a positive vision of the instructional goals. This vision is enhanced and authenticated by their own perspectives and interpretations. In addition, many teachers report notable improvements in students' ability to regulate their own behaviors related to time and task management. Figure 2.4 depicts a self-assessment rubric that can be used to supplement a content scoring rubric. This rubric requires students to assess not only their overall achievement but also the effort they actually put into the task. Students' completed self-assessment rubrics then support teacher-student conversations about the task outcomes. Essay Question: Who do you think was the most important president of the United States? Why? 1. Who do you think was the most important president? (e.g., I think (name of person) was the most important president of the United States.) 2. Why do you think he was the most important president? (e.g., I think (name of person) was the most important president because 3. What other characteristics made this person a great leader? (e.g., ___ (name of person) was also very knowledgeable about and skilled at 4. How do you know this? (e.g., I learned these facts about (name of person) by reading the book written by 5. What else did you learn about this president? (e.g., I was surprised to learn 6. Summarize or restate what you have learned or believe about the topic. (e.g., In summary, (name of person) was a very good leader whose ability to most important president of the United States.) could be used with a history class. As with all assessments, the teacher first must decide what a given tool will assess before implementing and drawing conclusions from it. In general, authentic assessment approaches, such as dialogue journals and scaffolded essays, benefit teachers and students because these assessment tools: - Provide more precise information about the student's learning and skills than traditional assessments - Support identification of the levels and types of scaffolding needed for students to demonstrate what they know or can do - Embed assessment within an instructional process that helps students acquire targeted skills - Increase students' awareness of how scaffolds can facilitate their learning Although they may not be aware of it, many classroom teachers already incorporate authentic assessment into their accommodated instruction for CLD students. Continual daily assessment helps teachers know when to modify instruction and when to strengthen (or reduce) supports or scaffolds to keep students challenged, engaged, and learning

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts