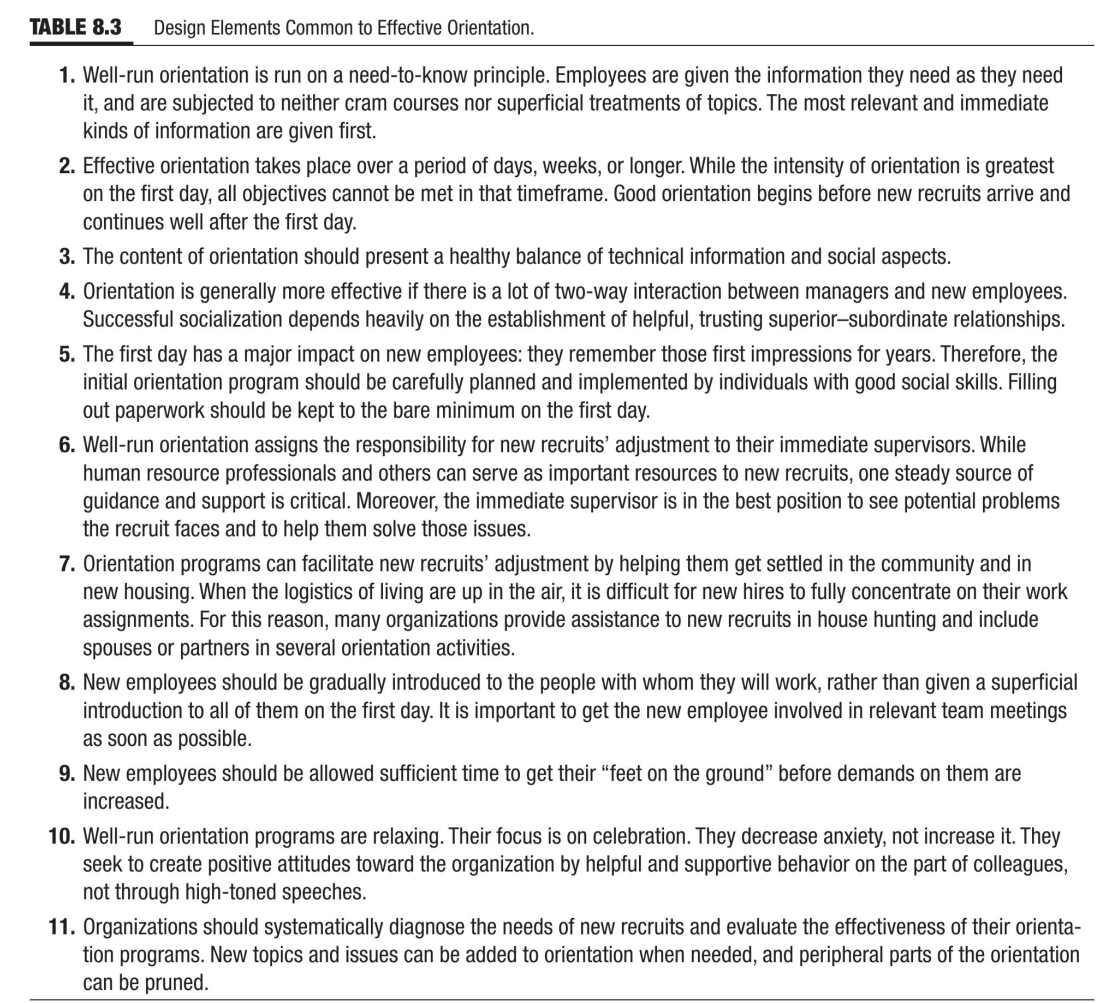

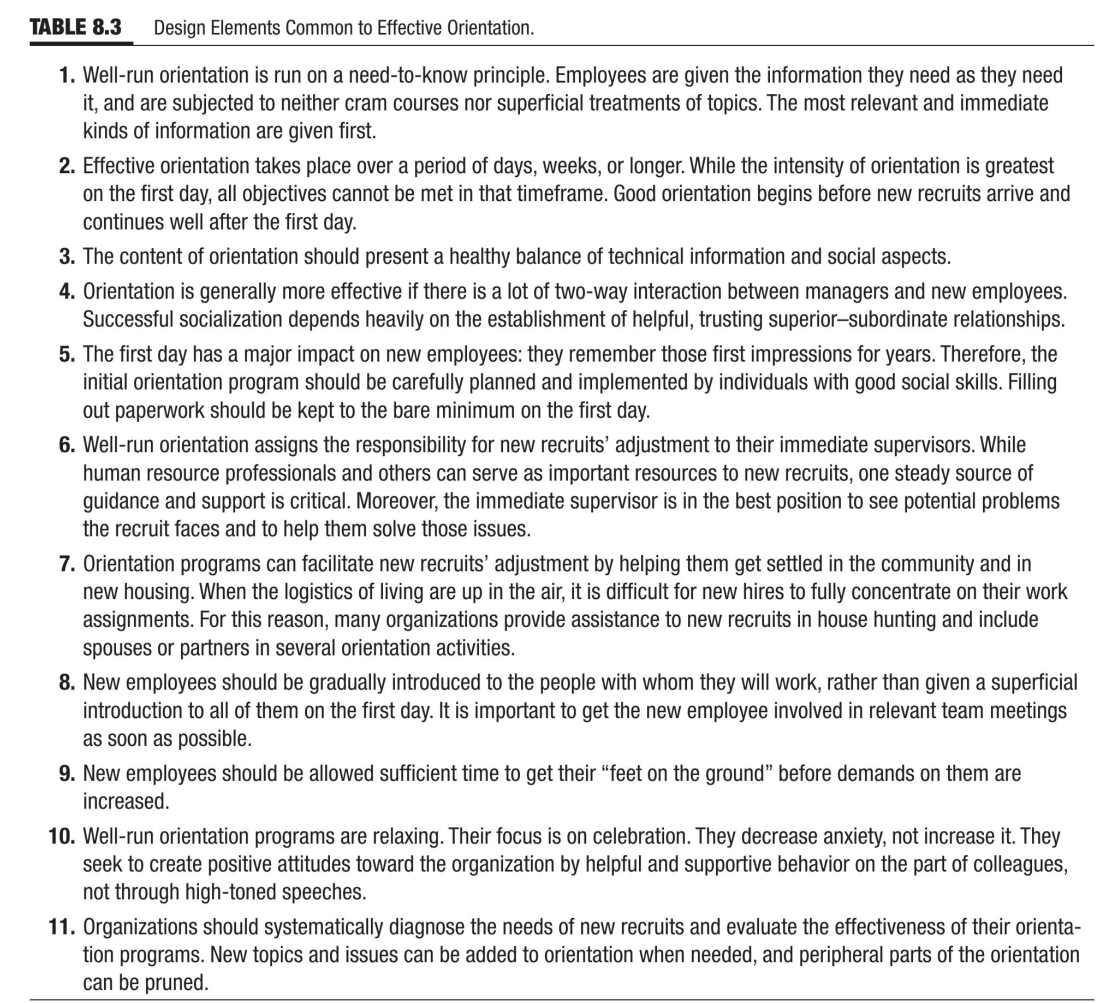

Question: Examine (Table 8.3 below) and describe ways it would also be relevant for 're-onboarding,' as described in case below. TABLE 8.3 Design Elements Common to

Examine (Table 8.3 below) and describe ways it would also be relevant for 're-onboarding,' as described in case below.

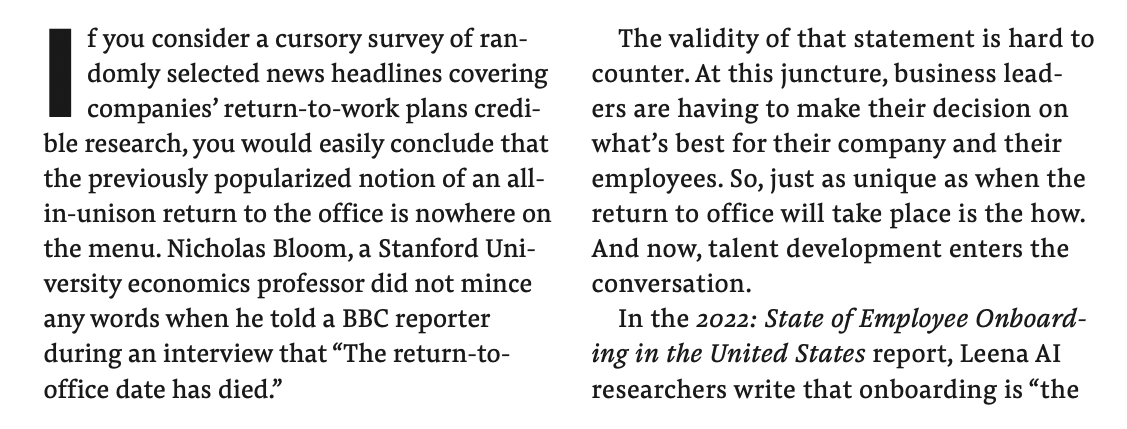

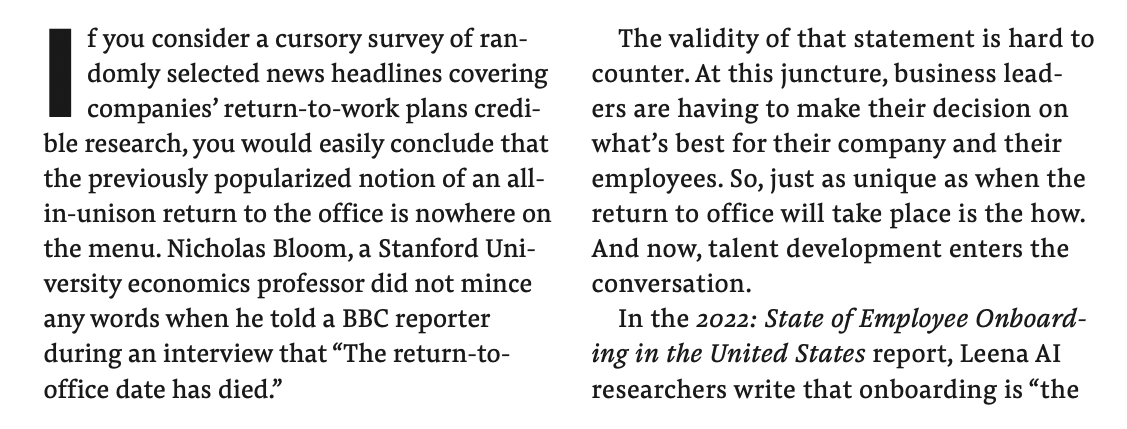

TABLE 8.3 Design Elements Common to Effective Orientation. 1. Well-run orientation is run on a need-to-know principle. Employees are given the information they need as they need it, and are subjected to neither cram courses nor superficial treatments of topics. The most relevant and immediate kinds of information are given first. 2. Effective orientation takes place over a period of days, weeks, or longer. While the intensity of orientation is greatest on the first day, all objectives cannot be met in that timeframe. Good orientation begins before new recruits arrive and continues well after the first day. 3. The content of orientation should present a healthy balance of technical information and social aspects. 4. Orientation is generally more effective if there is a lot of two-way interaction between managers and new employees. Successful socialization depends heavily on the establishment of helpful, trusting superior-subordinate relationships. 5. The first day has a major impact on new employees: they remember those first impressions for years. Therefore, the initial orientation program should be carefully planned and implemented by individuals with good social skills. Filling out paperwork should be kept to the bare minimum on the first day. 6. Well-run orientation assigns the responsibility for new recruits' adjustment to their immediate supervisors. While human resource professionals and others can serve as important resources to new recruits, one steady source of guidance and support is critical. Moreover, the immediate supervisor is in the best position to see potential problems the recruit faces and to help them solve those issues. 7. Orientation programs can facilitate new recruits' adjustment by helping them get settled in the community and in new housing. When the logistics of living are up in the air, it is difficult for new hires to fully concentrate on their work assignments. For this reason, many organizations provide assistance to new recruits in house hunting and include spouses or partners in several orientation activities. 8. New employees should be gradually introduced to the people with whom they will work, rather than given a superficial introduction to all of them on the first day. It is important to get the new employee involved in relevant team meetings as soon as possible. 9. New employees should be allowed sufficient time to get their "feet on the ground" before demands on them are increased. 10. Well-run orientation programs are relaxing. Their focus is on celebration. They decrease anxiety, not increase it. They seek to create positive attitudes toward the organization by helpful and supportive behavior on the part of colleagues, not through high-toned speeches. 11. Organizations should systematically diagnose the needs of new recruits and evaluate the effectiveness of their orienta- tion programs. New topics and issues can be added to orientation when needed, and peripheral parts of the orientation can be pruned. f you consider a cursory survey of ran- domly selected news headlines covering companies' return-to-work plans credi- ble research, you would easily conclude that the previously popularized notion of an all- in-unison return to the office is nowhere on the menu. Nicholas Bloom, a Stanford Uni- versity economics professor did not mince any words when he told a BBC reporter during an interview that "The return-to- office date has died." The validity of that statement is hard to counter. At this juncture, business lead- ers are having to make their decision on what's best for their company and their employees. So, just as unique as when the return to office will take place is the how. And now, talent development enters the conversation. In the 2022: State of Employee Onboard- ing in the United States report, Leena AI researchers write that onboarding is "the process of integrating a new employee into a company and its culture, as well as giving them the tools and informa- tion needed to become a productive member of the team." Conversely, re- boarding and re-onboarding are the popular terms many organization de- velopment practitioners are using to describe training programs and pro- cesses that acclimate all workers to a company's now culture. This reboarding or re-onboarding chatter isn't new. In fact, it was a trending topic much of 2021 when Fierce Conversations CEO Edward Bel- tran defined the terms as "the process of reintroducing employees to the workplace after an extended absence" in his Forbes article "A Guide To Reboarding Employees During And After The Pandemic." In it he also notes that "In the past, it often referred to reintegrating those em- ployees who had been on parental leave, had an extended illness or had been on temporary assignment elsewhere." Accordingly, TD professionals should think it not too far-fetched of an idea that 2022 could very well be the year that reboarding rebrands. Given that many TD functions don't have firsthand experience develop- ing postpandemic comeback training curriculums for companies, there is no model, and no two organizations will do it the same. And what that means for TD staff is that they will be tested in their agility and adapt- ability, and they may even dabble in some risk-taking as they ready their respective workforces for peak post- pandemic productivity. Reboarding rebranded Beltran's reboarding definition is a great starting point, but there is no seminal blueprint. Today, the tar- get audience for organization-wide reboarding extends far beyond em- ployees recovering from illness or returning from a temporary deploy- ment or parental leave. And with that evolution comes some new consid- erations for those in the TD function curating and creating employee come- back curriculums. "Part of companies' reboarding con- siderations should be the employees that are transitioning from a 100 per- cent remote work to working in the office," says Christina Gialleli, director of people operations at Epignosis, a learning technologies company. "Even though these employees have been with the company for a while, it makes sense applying some of the re-onboarding strategies to them in order to ensure a smooth transition." Jim Laughlin, vice president of lead- ership development and coaching services at MDA Leadership Con- sulting, highlights the silver lining lurking amid the cloudy chaos await- ing reboarding program designers. He suggests organizational leaders regard reboarding as a new beginning. "It should be viewed as a fresh chance to reinvigorate your employees and en- hance their passion about working for your organization," Laughlin explains. Though reboarding has been a trending topic among leaders in the or- ganization development space, Stephan Frettlhr, a senior client partner at Korn Ferry, anticipates that reboarding best practices are likely to evolve. "What we currently see is that the employee reboarding is mainly fo- cusing on logistics such as how office space is being organized to ensure distancing," he notes. "Many com- panies are starting to take a broader perspective and provide further sup- port to their employees, such as support in organizing hybrid work models to ensure both company and personal needs, offering trainings on how to manage/lead in hybrid envi- ronments and providing psychological support. Some are also providing sup- port organizing personal matters such as childcare." Comeback culture co-creators Whatever shape reboarding takes at your organization, crafting the train- ing game plan for a massive comeback is not something that the TD function should do in a silo. In an era where leading research think tanks confirm that workers value diversity, equity, and inclusion on the job now more than ever before, experts say TD pro- fessionals should be careful to include input from all levels of the enterprise when shaping reboarding strategies. "It is important when you develop a reboarding program to involve all stakeholders," Gialleli states. "To en- sure that the curriculum supports the organizational culture, the program de- velopers should inform and consult the leadership, the managers, but also get feedback from employees themselves." Natalie Grund, a senior leadership consultant at MDA Leadership Con- sulting, further explains the value of enlisting staff as co-creators of a sound reboarding program. "Employ- ees and frontline managers need to feel that they have some hand in shap- ing the terrain and co-creating the new world of work," she says. "Organizations should prepare to learn in waves, pro- viding sufficient clarity and alignment on such things as core values-based policies, yet remaining in a flexible learner's stance." Preciate CEO Ed Stevens also sees the value of being inclusive when build- ing reboarding programs. "Making your employees feel like an essential build- ing block of the company's strategy could unlock some creative insights and suggestions from them," he notes. "It's a chance to re-establish and foster company cultures and relationships." To succeed at reboarding develop- ment, Laughlin describes a framework that TD practitioners can use. "We rec- ommend a robust three-step process of ready, reboard, and reinvent that unfolds over a two- to three-month timeline, with tools, and practices to guide leaders before, during, and af- ter the return to on-site," he explains. "At the organizational level, reboarding should borrow from the success fac- tors required for major organizational change efforts, including a strong core reboarding team, stakeholder align- ment, continuous two-way feedback to enable course correction, and overcom- munication throughout." Transformation as the takeaway Tracking the success of reboarding pro- grams can be tricky, but Grund and Laughlin both believe that an effective program has the power to flatten any productivity decreases that can occur without a well-managed workplace re-entry initiative. Gialleli suggests focusing in on the qualitative results. "Survey your em- ployees. Ask them how they feel during the process, and even after they are back-perhaps at a cadence of 30, 60, or 90 days," she says. For Frettlhr, retention is a good barometer of a re- boarding program's success. Also, companies can use employee engage- ment with a focus on return to work as well as outside-in measures such as employer brand value, he adds. A word to the wise: While reboard- ing best practices remain fluid and in flux, now that return-to-office plans are focusing on the how of rolling out reboarding programs, TD practitioners should ready themselves now in antic- ipation of the high-level return-to-work conversations-if those discussions have not already begun. Moreover, ex- pect that reboarding's evolution will change traditional onboarding pro- grams too. The familiar has been dismantled- employees are entering a new era of working, relating, and operating. And let's not forget about the many peo- ple who started a new job remotely and have yet to experience their employer's in-office culture. That is only the begin- ning. Experts anticipate that the way the TD function handles the great rebrand of reboarding will likewise lead to ancil- lary changes to traditional onboarding. "The future is likely to see more per- sonalized, human-centered onboarding designed with greater attention to so- cial and emotional well-being, purpose, and belonging," Laughlin predicts. "It is also likely to extend further into the new employee's tenure, with more so- phisticated means to track their full participation in and satisfaction with the organization's culture." Indeed, the working world's future is in the TD function's hands. And as Frettlhr puts it, "Reboarding pro- grams will have to be fully integrated, as successful reboarding does not only ensure return to office after the pandemic as a one-off measure but it must become the starting point for organizations to transform into new ways of working and operating." Derrick Thompson is a former writer/ editor for ATD. TABLE 8.3 Design Elements Common to Effective Orientation. 1. Well-run orientation is run on a need-to-know principle. Employees are given the information they need as they need it, and are subjected to neither cram courses nor superficial treatments of topics. The most relevant and immediate kinds of information are given first. 2. Effective orientation takes place over a period of days, weeks, or longer. While the intensity of orientation is greatest on the first day, all objectives cannot be met in that timeframe. Good orientation begins before new recruits arrive and continues well after the first day. 3. The content of orientation should present a healthy balance of technical information and social aspects. 4. Orientation is generally more effective if there is a lot of two-way interaction between managers and new employees. Successful socialization depends heavily on the establishment of helpful, trusting superior-subordinate relationships. 5. The first day has a major impact on new employees: they remember those first impressions for years. Therefore, the initial orientation program should be carefully planned and implemented by individuals with good social skills. Filling out paperwork should be kept to the bare minimum on the first day. 6. Well-run orientation assigns the responsibility for new recruits' adjustment to their immediate supervisors. While human resource professionals and others can serve as important resources to new recruits, one steady source of guidance and support is critical. Moreover, the immediate supervisor is in the best position to see potential problems the recruit faces and to help them solve those issues. 7. Orientation programs can facilitate new recruits' adjustment by helping them get settled in the community and in new housing. When the logistics of living are up in the air, it is difficult for new hires to fully concentrate on their work assignments. For this reason, many organizations provide assistance to new recruits in house hunting and include spouses or partners in several orientation activities. 8. New employees should be gradually introduced to the people with whom they will work, rather than given a superficial introduction to all of them on the first day. It is important to get the new employee involved in relevant team meetings as soon as possible. 9. New employees should be allowed sufficient time to get their "feet on the ground" before demands on them are increased. 10. Well-run orientation programs are relaxing. Their focus is on celebration. They decrease anxiety, not increase it. They seek to create positive attitudes toward the organization by helpful and supportive behavior on the part of colleagues, not through high-toned speeches. 11. Organizations should systematically diagnose the needs of new recruits and evaluate the effectiveness of their orienta- tion programs. New topics and issues can be added to orientation when needed, and peripheral parts of the orientation can be pruned. f you consider a cursory survey of ran- domly selected news headlines covering companies' return-to-work plans credi- ble research, you would easily conclude that the previously popularized notion of an all- in-unison return to the office is nowhere on the menu. Nicholas Bloom, a Stanford Uni- versity economics professor did not mince any words when he told a BBC reporter during an interview that "The return-to- office date has died." The validity of that statement is hard to counter. At this juncture, business lead- ers are having to make their decision on what's best for their company and their employees. So, just as unique as when the return to office will take place is the how. And now, talent development enters the conversation. In the 2022: State of Employee Onboard- ing in the United States report, Leena AI researchers write that onboarding is "the process of integrating a new employee into a company and its culture, as well as giving them the tools and informa- tion needed to become a productive member of the team." Conversely, re- boarding and re-onboarding are the popular terms many organization de- velopment practitioners are using to describe training programs and pro- cesses that acclimate all workers to a company's now culture. This reboarding or re-onboarding chatter isn't new. In fact, it was a trending topic much of 2021 when Fierce Conversations CEO Edward Bel- tran defined the terms as "the process of reintroducing employees to the workplace after an extended absence" in his Forbes article "A Guide To Reboarding Employees During And After The Pandemic." In it he also notes that "In the past, it often referred to reintegrating those em- ployees who had been on parental leave, had an extended illness or had been on temporary assignment elsewhere." Accordingly, TD professionals should think it not too far-fetched of an idea that 2022 could very well be the year that reboarding rebrands. Given that many TD functions don't have firsthand experience develop- ing postpandemic comeback training curriculums for companies, there is no model, and no two organizations will do it the same. And what that means for TD staff is that they will be tested in their agility and adapt- ability, and they may even dabble in some risk-taking as they ready their respective workforces for peak post- pandemic productivity. Reboarding rebranded Beltran's reboarding definition is a great starting point, but there is no seminal blueprint. Today, the tar- get audience for organization-wide reboarding extends far beyond em- ployees recovering from illness or returning from a temporary deploy- ment or parental leave. And with that evolution comes some new consid- erations for those in the TD function curating and creating employee come- back curriculums. "Part of companies' reboarding con- siderations should be the employees that are transitioning from a 100 per- cent remote work to working in the office," says Christina Gialleli, director of people operations at Epignosis, a learning technologies company. "Even though these employees have been with the company for a while, it makes sense applying some of the re-onboarding strategies to them in order to ensure a smooth transition." Jim Laughlin, vice president of lead- ership development and coaching services at MDA Leadership Con- sulting, highlights the silver lining lurking amid the cloudy chaos await- ing reboarding program designers. He suggests organizational leaders regard reboarding as a new beginning. "It should be viewed as a fresh chance to reinvigorate your employees and en- hance their passion about working for your organization," Laughlin explains. Though reboarding has been a trending topic among leaders in the or- ganization development space, Stephan Frettlhr, a senior client partner at Korn Ferry, anticipates that reboarding best practices are likely to evolve. "What we currently see is that the employee reboarding is mainly fo- cusing on logistics such as how office space is being organized to ensure distancing," he notes. "Many com- panies are starting to take a broader perspective and provide further sup- port to their employees, such as support in organizing hybrid work models to ensure both company and personal needs, offering trainings on how to manage/lead in hybrid envi- ronments and providing psychological support. Some are also providing sup- port organizing personal matters such as childcare." Comeback culture co-creators Whatever shape reboarding takes at your organization, crafting the train- ing game plan for a massive comeback is not something that the TD function should do in a silo. In an era where leading research think tanks confirm that workers value diversity, equity, and inclusion on the job now more than ever before, experts say TD pro- fessionals should be careful to include input from all levels of the enterprise when shaping reboarding strategies. "It is important when you develop a reboarding program to involve all stakeholders," Gialleli states. "To en- sure that the curriculum supports the organizational culture, the program de- velopers should inform and consult the leadership, the managers, but also get feedback from employees themselves." Natalie Grund, a senior leadership consultant at MDA Leadership Con- sulting, further explains the value of enlisting staff as co-creators of a sound reboarding program. "Employ- ees and frontline managers need to feel that they have some hand in shap- ing the terrain and co-creating the new world of work," she says. "Organizations should prepare to learn in waves, pro- viding sufficient clarity and alignment on such things as core values-based policies, yet remaining in a flexible learner's stance." Preciate CEO Ed Stevens also sees the value of being inclusive when build- ing reboarding programs. "Making your employees feel like an essential build- ing block of the company's strategy could unlock some creative insights and suggestions from them," he notes. "It's a chance to re-establish and foster company cultures and relationships." To succeed at reboarding develop- ment, Laughlin describes a framework that TD practitioners can use. "We rec- ommend a robust three-step process of ready, reboard, and reinvent that unfolds over a two- to three-month timeline, with tools, and practices to guide leaders before, during, and af- ter the return to on-site," he explains. "At the organizational level, reboarding should borrow from the success fac- tors required for major organizational change efforts, including a strong core reboarding team, stakeholder align- ment, continuous two-way feedback to enable course correction, and overcom- munication throughout." Transformation as the takeaway Tracking the success of reboarding pro- grams can be tricky, but Grund and Laughlin both believe that an effective program has the power to flatten any productivity decreases that can occur without a well-managed workplace re-entry initiative. Gialleli suggests focusing in on the qualitative results. "Survey your em- ployees. Ask them how they feel during the process, and even after they are back-perhaps at a cadence of 30, 60, or 90 days," she says. For Frettlhr, retention is a good barometer of a re- boarding program's success. Also, companies can use employee engage- ment with a focus on return to work as well as outside-in measures such as employer brand value, he adds. A word to the wise: While reboard- ing best practices remain fluid and in flux, now that return-to-office plans are focusing on the how of rolling out reboarding programs, TD practitioners should ready themselves now in antic- ipation of the high-level return-to-work conversations-if those discussions have not already begun. Moreover, ex- pect that reboarding's evolution will change traditional onboarding pro- grams too. The familiar has been dismantled- employees are entering a new era of working, relating, and operating. And let's not forget about the many peo- ple who started a new job remotely and have yet to experience their employer's in-office culture. That is only the begin- ning. Experts anticipate that the way the TD function handles the great rebrand of reboarding will likewise lead to ancil- lary changes to traditional onboarding. "The future is likely to see more per- sonalized, human-centered onboarding designed with greater attention to so- cial and emotional well-being, purpose, and belonging," Laughlin predicts. "It is also likely to extend further into the new employee's tenure, with more so- phisticated means to track their full participation in and satisfaction with the organization's culture." Indeed, the working world's future is in the TD function's hands. And as Frettlhr puts it, "Reboarding pro- grams will have to be fully integrated, as successful reboarding does not only ensure return to office after the pandemic as a one-off measure but it must become the starting point for organizations to transform into new ways of working and operating." Derrick Thompson is a former writer/ editor for ATD