Question: Exercise 2.2: Suppose that preferences are given by the utility function u(c, l) = ln(c) + ? ln(l), where ? > 0 is a preference

Exercise 2.2: Suppose that preferences are given by the utility function u(c, l) = ln(c) + ? ln(l), where ? > 0 is a preference parameter. For these preferences, one can demonstrate that MRS(c, l) = ?c/l. Use this information, together with the conditions in (11) to solve explicitly for consumer demand, the demand for leisure and (from the time constraint) the supply of labor.

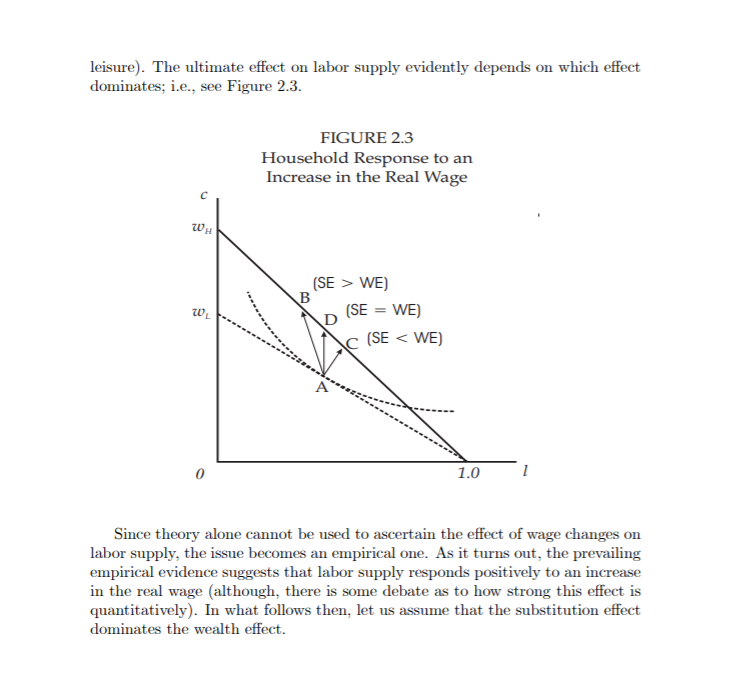

Exercise 2.2: Suppose that preferences are given by the utility mction u{c, I) = ln[c) + Alma], where A b 0 is a preference parameter. For those preferences, one can demonstrate that MRS[C,I) 2 Ac)\". Use this inEm-ination, together with the conditions in (11) to solve explicitly lor consumer demand, the demand for leisure and {From the time constraint] the supply of labor. The theory developed here makes clear that the allocation of time to market work [the supply of labor) should depend on the return to work relative other potential uses of time (in this simple model, leisure is the only alternative). The return to work here is given by the real wage. Intuitively, one would expect that an exogenous increase in the real wage might lead a household to reduce its demand for leisure {and hence, increase labor supply). While this intuition is not incorrect, it needs to be qualied. We can discover how by wayofasimple diagram. Figure 2.3 depicts how a household's desired behavior may change with an increase in the return to labor. Let allocation A in Figure 2.3 depict desired behavior for a low real wage, wL. Now, iinagine that the real wage rises to my 1: 1111,. Figure 2.3 (again, drawn for the case in which d = 0) shows that the household may respond in three general ways, represented by the alloca tions 3,0, and D. In each of these cases, consumer demand is predicted to rise. However, the eect on labor supply is, in general, ambiguous. Why is this the case? An increase in the real wage has two effects on the household budget. First, the price of leisure (relative to consumption) increases. Our intuition sug gests that households will respond to this price change by substituting into the cheaper commodity [i.e., from leisure into consumption, with the implied increase in labor supply). This is called the substitution e'ect. Second, household wealth (measured in units of output) increases. Recall that both con sumption and leisure are awumed to be normal goods. The logic of the model therefore implies that the demand for both consumption and leisure should rhe along with wealth with the increase in leisure coming at the expense of labor, This is called the wealth e'ect. Both of these effects work in the same di rection for consumption {which is why consumer demand must rise}. However, these effects work in opposite directions for labor supply (or the demand for leisure). The ultimate effect on labor supply evidently depends on which eect dominates; i.e., see Figure 23. FIGURE 23 Household Response to an Increase in the Real Wage Since theory alone cannot be used to ascertain the effect of wage changes on labor supply, the issue becomes an empirical one. As it turns out, the prevailing empirical evidence suggests that labor supply responds positively to an increase in the real wage (although, there is some debate as to how strong this effect is quantitatively). In what follows then, let us assume that the substitution eect dominates the wealth effect

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts