Question: For the questions, you will be expected to answer in no less than 500 words and no more than 800 words. You will also be

For the questions, you will be expected to answer in no less than 500 words and no more than 800 words. You will also be expected to use a specific example as a demonstration of your response. You will need to provide APA formatted in-text citations and references for any information sourced from a reference. This week and the assignment last week reviewed the continued evolution of tourism and destination management with an eye towards preservation. Preservation in this sense is a general term related to protecting the environment, the culture, the economy, and the demand for the location. Using a specific example demonstrating policies aimed at sustainability, how can culture be preserved with the influx of international travelers? As an aspect of your answer reference the four perspectives presented by David Weaver in the book Sustainable Tourism; Advocacy, Cautionary, Adaptancy, and Knowledge-Based. The information is presented in chapter 1, starting on page 5.

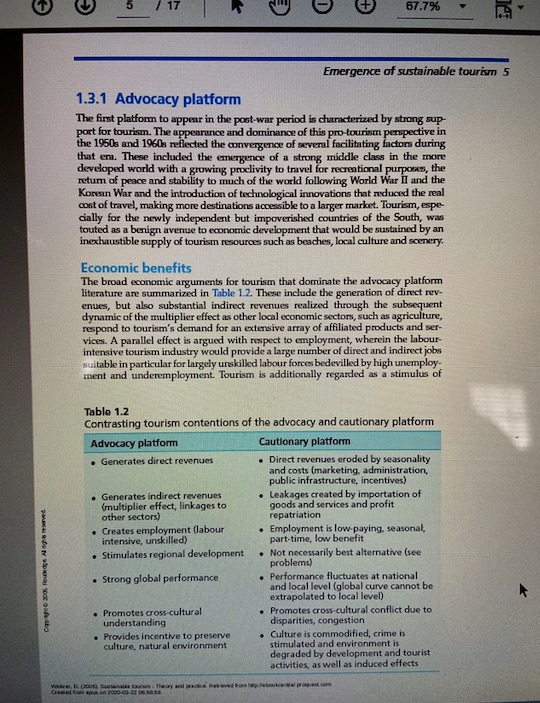

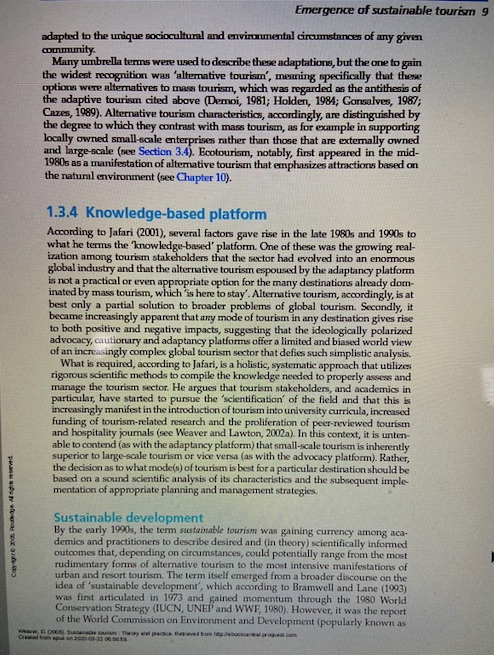

0 5 17 67.7% - - Emergence of sustainable tourism 5 1.3.1 Advocacy platform The first platform to appear in the post-war period is churacterized by strong sup port for tourism. The appearance and dominance of this pro tourism perspective in the 1950s and 1960s reflected the convergence of several facilitating factors during that era. These included the emergence of a strong middle class in the more developed world with a growing proclivity to travel for recrentional purposes, the retum of peace and stability to much of the world following World War II and the Konan War and the introduction of technological innovations that reduced the real cost of travel, making more destinations accessible to a larger market. Tourism, espe- cially for the newly independent but impoverished countries of the South, was touted as a benign avenue to economic development that would be sustained by an inexhaustible supply of tourism resources such as beaches, local culture and scenery. Economic benefits The broad economic arguments for tourism that dominate the advocacy platform literature are summarized in Table 1.2. These include the generation of direct rev- enues, but also substantial indirect revenues realized through the subsequent dynamic of the multiplier effect as other local economic sectors, such as agriculture, respond to tourism's demand for an extensive array of affiliated products and ser vices. A parallel effect is argued with respect to employment, wherein the labour intensive tourism industry would provide a large number of direct and indirect jobs suitable in particular for largely unskilled labour forces bedevilled by high unemploy. ment and underemployment. Tourism is additionally regarded as a stimulus of Tablo 1.2 Contrasting tourism contentions of the advocacy and cautionary platform Advocacy platform Cautionary platform Generates direct revenues Direct revenues eroded by seasonality and costs (marketing, administration, public infrastructure, incentives) Generates indirect revenues Leakages created by importation of (multiplier effect, linkages to goods and services and profit other sectors) repatriation Creates employment (labour Employment is low.paying, seasonal, intensive, unskilled) part-time, low benefit Stimulates regional development Not necessarily best alternative (see problems) Strong global performance Performance fluctuates at national and local level (global curve cannot be extrapolated to local level) Promotes cross-cultural Promotes cross-cultural conflict due to understanding disparities, congestion . Provides incentive to preserve Culture is commodified, crime is culture, natural environment stimulated and environment is degraded by development and tourist activities, as well as induced effects 2005 Rus 6 Sustainable Tourism economic development in peripheral regions experiencing stagrution or decline in the primary sector but lacking the potential to accommodate large-scale industrial ization or other alternatives. Conversely, tourism is thought to provide a way of revitalizing declining industrial cities such as Lowell, Massachusetts (USA) through the presentation of its industrial heritage as tourist attractions (McNulty, 1985). In the context of modemization theory (Rostow, 1960), tourism serves as a propulsive activity within select growth poles to stimulate economic growth and consequent 'trickle down' effects. This stimulus, moreover, would be sustained by touristn's record of robust growth, as evidenced in the visitation statistics of Table 1.1. Sociocultural and environmental benefits Purported social and cultural benefits augment the economic arguments that dorin- ate the advocacy platform. One of these is the idea that tourism promotes CIOSS- cultural understanding and ultimately, world peace, through direct contact between host and guest (D'Amore, 1988). Moreover, tourism provides an incentive to pre- serve a destination's unique environmental, cultural and historical assets, from which a portion of the revenue can be allocated for ongoing restoration and mainten- ance purposes. By this logic, iconic heritage sites such as the Great Wall of China, the Egyptian pyramids and the Civil War battlefields of the UK and USA would be seriously compromised in the absence of tourist-related interest and revenue. Mings (1969), in supporting tourism as an ideal economic sector for the Caribbean region, offers a good illustration of the advocacy perspective as it was presented earlier in the post-war period. His argument is essentially that the small islands of the Caribbean lack the resources and scale to base their economic development on a policy of industrialization, but are ideally suited because of their resources and large cheap labour forces to offer resort-based tourism opportunities to proximate markets such as the USA. Characteristic of this and much of the other advocacy literature is an uncritical approach that views tourism as a panacea. Accordingly, representatives of this platform usually implicitly or explicitly endorse a 'continual growth' approach to tourism development which holds that if a little tourism is a good thing, then more tourism must be even better. This pro-growth sentiment is consistent with the widespread support within this platform for free market capitalism as a vehicle that best facilitates this growth and yields significant economic benefits. Representatives of the advocacy platform, however, as with all the other perspec. tives, are not homogeneous in their beliefs. An interventionist element, for example, is evident among supporters of the above-mentioned growth pole theory, who hold that government should take the lead role in establishing conditions conducive to market-sustained economic development and spatial diffusion through tourism. Cancn and the other tourism-based growth poles of Mexico are a good example of this approach (Truett and Truett, 1982). 1.3.2 Cautionary platform Several factors contributed in the late 1960s and early 1970s to the emergence of the cautionary platform, which basically argues that unregulated tourism development eventually culminates in unacceptably high environmental, economic and sociocul tural costs for the residents of destinations, who have the most to lose as a result of these costs. A major factor was the intensification of tourism development in many Emergence of sustainable tourism 7 places (sisted by planners and officials supportive of the advocacy approach) and within less developed regions in particular, to a level where the rwynative impacts became increasingly evident. Concurrently, 'dependency t ry and other to Marcist corrumentaries provided a convenient framework within which these impacts, and the international tourism systean in general, could be contextualized. Focusing especially on the pleasure periphery, the dependency theorists contended that tourism, like plantation agriculture in a previous ern, was a means through which the developed core regions continued their exploitation and domination of the 'underdeveloped periphery (Hills and Lundgren, 1977; Britton, 1962). It is through this logic that Finney and Watson (1975) consider tourism as a new kind of sugar', while Harrigan (1974) accuse tourism of perpetuating the master clave relationships of slavery. An additional factor was the emergence of the environmental movement and its popularization through such breakthrough works as Silent Spring (Carson, 1962). Small is Bautifil (Schumacher, 1973) and Cai: A New Look at Life on Earth (Lawelock, 1979). Knill (1991) associates this movement more broadly with the appearance of a gre paradigm that has challenged the alleged exploitative and anthropocentric premises of the dominant westem environmental paradigm' ue Chapter 4). Repre. sentatives of this environmental strand of the cautionary platfon include Crittendon (1975), who emphasized the negative impacts of tourism on wildlife, and Budowski (1976), who maintained that the relationship between tourism and the natural envir- onment was mostly one of neutral 'coexistence that was, however, moving toward 'conflict' as tourism continued to expand haphazardly into relatively unspoiled areas. The ideal serurio of symbiosis', according to Budowski, is rarely encountered. Economic costs As outlined in Table 1.2, supporters of this platform, many of who are not strict dependency theorists or environmentalists (eg English, 1986, Lea, 1988), typically cite a counter argument to every supposed benefit put forward by tourism advocates. Where the advocacy platform extols the generation of substantial direct revenues, sup porters of the cautionary platform cite accelerating marketing, incentive and adminis. trative costs that significantly erode these revenues as destinations become more competitive and bureaucracies more bloated. Where the former note the auxiliary bene fits of the multiplier effect, the latter contend that this is minimal or non-existent due to revenue leakages associated with local economies too weak to generate meaningful linkages with tourism. Tourism employment, moreover, is decried as chronically low- wage, part-time and seasonal, as well as bereft of employee benefits or opportunities for upward mobility. And while a long-term pattern of sustained growth exists at the global scale, individual destinations are subject to unpredictable and potentially dev. astating fluctuations due to competition from other tourism destinations and products as well as the sensitivity of tourist markets to political and environmental instability The seasonal nature of tourist demand, moreover, tends to create a regular 'drought deluge cycle that respectively induces periods of under-capacity and over-capacity. These factors combine, ultimately, to reduce the effectiveness of tourism as an agent of economic development in peripheral or depressed regions. Sociocultural and environmental costs In the sociocultural arena, supporters of the cautionary platform contend that tourism is just as likely to foster misunderstanding and conflict, rather than harmony www.D. (2008). Theory and pre ved from puber t .com 8 Sustainable Tourism and world pence, due to the cultural divide and disparities in wealth that often occur between host and guest and to the in situ nature of tourism promption (ie, tourism products are produced and consumed at the same location. Frustration over.com gestion and the diversion of murvices and mounts to tourists may also incrow the likelihood of conflict. The incentive effect may be offset by the commodification effect as residents adapt products and services to the demands of the tourist market rather than the needs of their own community (Cohen, 1988). Increased tourism activity is also associated with increased crime in destirutions such as the Gold Coast of Australia (Prideaux and Dunn, 1995), in part because the tourist is an attractive target and in part because some tourists (eg, paedophiles visiting Cambodia, or football hooligans from the UK travelling to France) intend to engage in illegal or criminal activity With regard to the natural environment, foundation assets such as beaches, forests and lakes, as per Budowski (1976) and Crittendon (1975) (see above), become congested and polluted due to pressures arising from tourism-related construction, waste generation and visitor activity, thereby neutralizing the incentive effect. Indirect construction and waste, often on a much greater sale, is also associated with the need to provide housing and services for workers in the tourism industry and their dependents (Weaver and Lawton, 2002a). It is argued that these cultural and environmental modifications ultimately give rise to a homogeneous 'inter national tourism landscape that destroys the destination's unique 'sense of place w level of the positive rise to rapid toured. It is Destination life cycle model The well-known destination life cycle mode of Butler (1980) may be regarded as the culmination of the cautionary platform given its contention that unregulated tourism development eventually undermines the very foundation assets that support the growth of a tourist destination in the first instance. The Scurved model begins with a low-level equilibrium 'exploration stage during which the impacts of the embryonic tourist flow, either positive or negative, are negligible. Local responses to the incipient tourist traffic eventually give rise to a transitional involvement stage, which is soon in tum superseded by a period of rapid tourism development' as the destination experiences and responds to accelerated demand. It is during this stage of mass tourism onset that the problems cited above become significant and eventually cause the critical environmental, sociocultural and economic carrying capacities of the destin- ation to be breeched. 'Consolidation' and 'stagnation' and then 'decline successively occur if industry or government undertakes no remedial intervention. Alternatively, rejuvenation' is possible if such measures are implemented. The assumptions of the destination life cycle model, like the cautionary platform in general, are not inherently hostile to tourism, but contend that unregulated tourism contains within itself the seeds of its own destruction. Hence, it is assumed that a high level of public sector intervention is necessary to ensure that deterioration does not occur. 1.3.3 Adaptancy platform The cautionary platform identified the potential negative impacts of tourism, but did not articulate models of tourism that would avoid these effects and actually realize the array of benefits described by the supporters of the advocacy platform. The appearance in the late 1970s and early 1980s of discussion on perceived solutions marks the beginning of the adaptancy platform, a perspective aligned ideologically with the cautionary platform that is so called because it espouses tourism that is de colorate Emergence of sustainable tourism 9 adapted to the unique sociocultural and envirrunental circumstances of any given Community Many umbrella terms were used to describe these adaptations, but the one to gain the widest recognition was 'alternative tourism', mesning specifically that the options were alternatives to mass tourism, which was regarded as the antithesis of the adaptive tourism cited above (Demoi, 1981; Holden, 1984; Gonsalves, 1987, Cazes, 1989). Alternative tourism characteristics, accordingly, are distinguished by the degree to which they contrast with mass tourism, as for example in supporting locally owned small-scale enterprises rather than those that are externally owned and large-scale (see Section 3.4). Ecotourism, notably, first appeared in the mid- 1980s as a manifestation of alternative tourism that emphasizes attractions based on the natural environment (see Chapter 10). 1981How Sarded as the en chans 1.3.4 Knowledge-based platform According to Jafari (2001), several factors gave rise in the late 1980s and 1990s to what he terms the knowledge-based platform. One of these was the growing real- iration among tourism stakeholders that the sector had evolved into an enormous global industry and that the alternative tourism espoused by the adaptancy platform is not a practical or even appropriate option for the many destinations already dom inated by mass tourism, which is here to stay'. Alternative tourism, accordingly, is at best only a partial solution to broader problems of global tourism. Secondly, it became increasingly apparent that any mode of tourism in any destination gives rise to both positive and negative impacts, suggesting that the ideologically polarized advocacy, cautionary and adaptancy platforms offer a limited and biased world view of an increasingly complex global tourism sector that defies such simplistic analysis. What is required, according to Jafari, is a holistic, systematic approach that utilizes rigorous scientific methods to compile the knowledge needed to properly assess and manage the tourism sector. He argues that tourism stakeholders, and academics in particular, have started to pursue the 'scientification of the field and that this is increasingly manifest in the introduction of tourism into university curricula, increased funding of tourism-related research and the proliferation of peer-reviewed tourism and hospitality journals (see Weaver and Lawton, 2002a). In this context, it is unten able to contend (as with the adaptancy platform) that small-scale tourism is inherently superior to large-scale tourism or vice versa (as with the advocacy platform). Rather, the decision as to what mode(s) of tourism is best for a particular destination should be based on a sound scientific analysis of its characteristics and the subsequent imple. mentation of appropriate planning and management strategies Sustainable development By the early 1990s, the term sustainable tourism was gaining currency among aca- demics and practitioners to describe desired and (in theory) scientifically informed outcomes that, depending on circumstances, could potentially range from the most rudimentary forms of alternative tourism to the most intensive manifestations of urban and resort tourism. The term itself emerged from a broader discourse on the idea of 'sustainable development, which according to Bramwell and Lane (1993) was first articulated in 1973 and gained momentum through the 1980 World Conservation Strategy (IUCN, UNEP and WWE, 1980). However, it was the report of the World Commission on Environment and Development (popularly known as 10 Sustainable Tourism the Brundtland Report, after the name of the Commission's Chair) which popular ized the concept in the late 1980s, defining sustainable development as 'develop- ment that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs' (WCED), 1987, p. 43). Esentially, sustainable development 'advocates the wise use and conservation of our in order to maintain their long-term viability (Eber, 1992, p. 1). The subsequent extent to which the concept of sustainable development has become almost universally endorsed as a desired process is truly remarkable. Aside from the credentials of the Commission and the high level endomment by the United Nations that followed in evidence for example at the 1992 Rio Earth Summit), this support an be explained in part by the appealing muntics of the term, which offers the prospect of development for the supporters of continued growth, but the prospect of sustainability for environmentalists and other advocates of a slow growth or steady state approach. Synthesizing these two contradictory strands, sustainable development represents the attractive posibility of continuing economic development that does not unduly strain the earth's environmental, socio- cultural or economic carrying capacities. Sustainable tourism Sustainable tourism may be regarded most basically as the application of the sun tainable development idea to the tourism sector that is, tourism development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future gener ations to meet their own needs or, in concert with Budowski's (1976) 'symbiosis' scenario (see Section 13.2), tourism that wisely uses and conserves resources in order to maintain their long-term viability. Essentially, sustainable tourism involves the minimization of negative impacts and the maximization of positive impacts. Yet, while sustainable tourism may therefore be regarded as a form of sustainable development (ie, development as a process) as well as a vehicle for achieving the Latter (ie development as a goal), there is not as direct a relationship between the two terms as might be expected. The Brundtland Report, curiously, makes no men- tion of tourism even though the latter had already attained 'megasector' status by the mid-1980s. This neglect was evident several years later in the Agenda 21 strategy document that emerged from the seminal Rio Earth Summit in 1992, which made only a few incidental references to tourism as both a cause and potential ameliorator of environmental and social problems (UNCED, 1992). It was, rather, among tourism academics and organizations, or those especially aware of the sector's great potential to generate both costs and benefits, that discus sions explicitly using the term sustainable tourism first emerged in the early 1990s (see for example Pigram, 1990; Dearden, 1991; Inskeep, 1991; Lane, 1991; Manning, 1991; Bull, 1972; D Amore, 1992: Eber, 1992: Zurick, 1992). A notable development was the inauguration of the peer reviewed journal of Sustainable Tourism in 1993. Preceding this literature is earlier material, notably by Murphy (1985) and Krippendorf (1987). that does not use the term 'sustainable tourism' explicitly (they respectively refer to community-based tourism and soft tourism, but espouse similar principles in re erence to mass tourism, which they regard as legitimate. Similar sentiments are evi dent in contemporary deliberations involving the World Tourism Organization and the United Nations (WTO, 1985, 1989; WTO and UNEP, 1982, 1983). Distinguishing the work of the 1990s, however, was reference to the broader discourse on sustainable development as a basis for proposing strategies that would achieve a more sustain able tourism sector