Question: here are some notes that may help with the question Expected Utility: The expected utility of a lottery p is: Eu(p)=i=1np(xi)u(xi) The function u:XR is

here are some notes that may help with the question

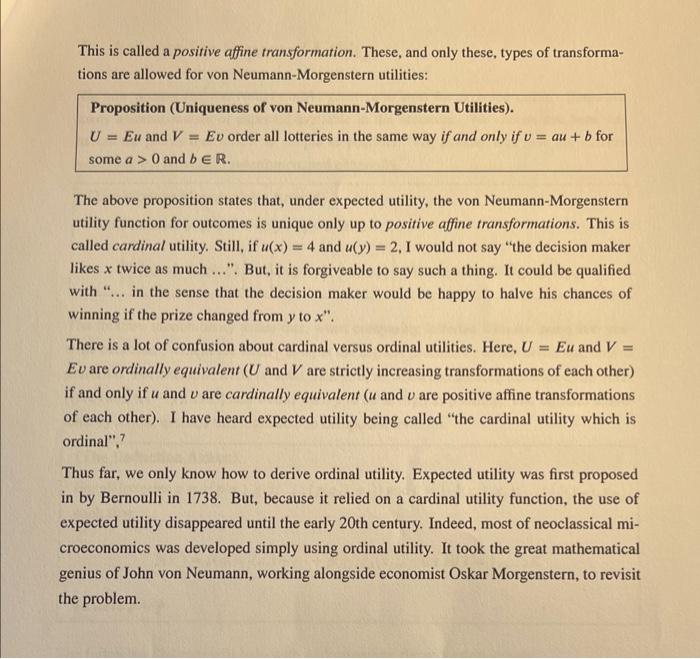

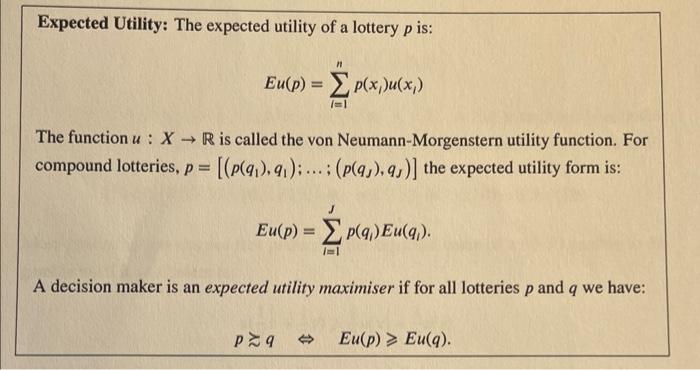

Expected Utility: The expected utility of a lottery p is: Eu(p)=i=1np(xi)u(xi) The function u:XR is called the von Neumann-Morgenstern utility function. For compound lotteries, p=[(p(q1),q1);;(p(qJ),qJ)] the expected utility form is: Eu(p)=i=1Jp(qi)Eu(qi) A decision maker is an expected utility maximiser if for all lotteries p and q we have: pqEu(p)Eu(q) 2.2 Risk Aversion. Risk aversion is the condition that a decision maker prefers the expected value of a lottery, offered with certainty, over the lottery itself. For example, the fair coin-toss that pays 20 on heads and 10 on tails. p=[(0.5,20):(0.5,10)] has expected value E(p)=0.5(20)+0.5(10)=15. A risk averse decision maker prefers 15 with certainty over this coin-toss lottery. Under expected utility, this means: 15[(0.5,20):(0.5,10)]u(15)0.5u(20)+0.5u(10). More generally, you can see that preferring the expected value of a 5050 gamble to the gamble itself is equivalent to: u(21x+21y)21u(x)+21u(y) which holds if u is a concave function. The general definition of risk aversion is as follows: Risk Aversion. A decision maker is risk averse if for all money lotteries p we have E(p)p. An expected utility maximiser is risk averse if for all money lotteries p we have: u(i=1Kp(xi)xi)i=1Kp(xi)u(xi) which is equivalent to the von Neumann-Morgenstern utility u being a concave function (an immediate implication of Jensen's inequality). The definitions of risk neutrality and risk seeking are analogous to the definition of risk aversion, merely replacing with or , respectively. It is commonly assumed in eco- function that is strictly increasing u>0 (more money is better) and that u is strictly concave uEu(q) but Ev(p)0 and bR : au(14)+b=21(au(20)+b)+21(au(10)+b). This is called a positive affine transformation. These, and only these, types of transformations are allowed for von Neumann-Morgenstern utilities: Proposition (Uniqueness of von Neumann-Morgenstern Utilities). U=Eu and V=Ev order all lotteries in the same way if and only if v=au+b for some a>0 and bR. The above proposition states that, under expected utility, the von Neumann-Morgenstern utility function for outcomes is unique only up to positive affine transformations. This is called cardinal utility. Still, if u(x)=4 and u(y)=2, I would not say "the decision maker likes x twice as much ..... But, it is forgiveable to say such a thing. It could be qualified with "... in the sense that the decision maker would be happy to halve his chances of winning if the prize changed from y to x. There is a lot of confusion about cardinal versus ordinal utilities. Here, U=Eu and V= Ev are ordinally equivalent ( U and V are strictly increasing transformations of each other) if and only if u and v are cardinally equivalent ( u and v are positive affine transformations of each other). I have heard expected utility being called "the cardinal utility which is ordinal" 7 Thus far, we only know how to derive ordinal utility. Expected utility was first proposed in by Bernoulli in 1738. But, because it relied on a cardinal utility function, the use of expected utility disappeared until the early 20 th century. Indeed, most of neoclassical microeconomics was developed simply using ordinal utility. It took the great mathematical genius of John von Neumann, working alongside economist Oskar Morgenstern, to revisit the problem. Expected Utility: The expected utility of a lottery p is: Eu(p)=i=1np(xi)u(xi) The function u:XR is called the von Neumann-Morgenstern utility function. For compound lotteries, p=[(p(q1),q1);;(p(qJ),qJ)] the expected utility form is: Eu(p)=i=1Jp(qi)Eu(qi) A decision maker is an expected utility maximiser if for all lotteries p and q we have: pqEu(p)Eu(q) 2.2 Risk Aversion. Risk aversion is the condition that a decision maker prefers the expected value of a lottery, offered with certainty, over the lottery itself. For example, the fair coin-toss that pays 20 on heads and 10 on tails. p=[(0.5,20):(0.5,10)] has expected value E(p)=0.5(20)+0.5(10)=15. A risk averse decision maker prefers 15 with certainty over this coin-toss lottery. Under expected utility, this means: 15[(0.5,20):(0.5,10)]u(15)0.5u(20)+0.5u(10). More generally, you can see that preferring the expected value of a 5050 gamble to the gamble itself is equivalent to: u(21x+21y)21u(x)+21u(y) which holds if u is a concave function. The general definition of risk aversion is as follows: Risk Aversion. A decision maker is risk averse if for all money lotteries p we have E(p)p. An expected utility maximiser is risk averse if for all money lotteries p we have: u(i=1Kp(xi)xi)i=1Kp(xi)u(xi) which is equivalent to the von Neumann-Morgenstern utility u being a concave function (an immediate implication of Jensen's inequality). The definitions of risk neutrality and risk seeking are analogous to the definition of risk aversion, merely replacing with or , respectively. It is commonly assumed in eco- function that is strictly increasing u>0 (more money is better) and that u is strictly concave uEu(q) but Ev(p)0 and bR : au(14)+b=21(au(20)+b)+21(au(10)+b). This is called a positive affine transformation. These, and only these, types of transformations are allowed for von Neumann-Morgenstern utilities: Proposition (Uniqueness of von Neumann-Morgenstern Utilities). U=Eu and V=Ev order all lotteries in the same way if and only if v=au+b for some a>0 and bR. The above proposition states that, under expected utility, the von Neumann-Morgenstern utility function for outcomes is unique only up to positive affine transformations. This is called cardinal utility. Still, if u(x)=4 and u(y)=2, I would not say "the decision maker likes x twice as much ..... But, it is forgiveable to say such a thing. It could be qualified with "... in the sense that the decision maker would be happy to halve his chances of winning if the prize changed from y to x. There is a lot of confusion about cardinal versus ordinal utilities. Here, U=Eu and V= Ev are ordinally equivalent ( U and V are strictly increasing transformations of each other) if and only if u and v are cardinally equivalent ( u and v are positive affine transformations of each other). I have heard expected utility being called "the cardinal utility which is ordinal" 7 Thus far, we only know how to derive ordinal utility. Expected utility was first proposed in by Bernoulli in 1738. But, because it relied on a cardinal utility function, the use of expected utility disappeared until the early 20 th century. Indeed, most of neoclassical microeconomics was developed simply using ordinal utility. It took the great mathematical genius of John von Neumann, working alongside economist Oskar Morgenstern, to revisit the

![is called the von Neumann-Morgenstern utility function. For compound lotteries, p=[(p(q1),q1);;(p(qJ),qJ)] the](https://dsd5zvtm8ll6.cloudfront.net/si.experts.images/questions/2024/09/66e534d539a88_30066e534d4b6a8f.jpg)