Question: I need help on solving and answering this question. First here is some textbook pages that could be helpful for reference P11.9.85 [XC 10 pts]

I need help on solving and answering this question.

First here is some textbook pages that could be helpful for reference

![textbook pages that could be helpful for reference P11.9.85 [XC 10 pts]](https://dsd5zvtm8ll6.cloudfront.net/si.experts.images/questions/2024/10/6703ec4542c51_3416703ec4510ebc.jpg)

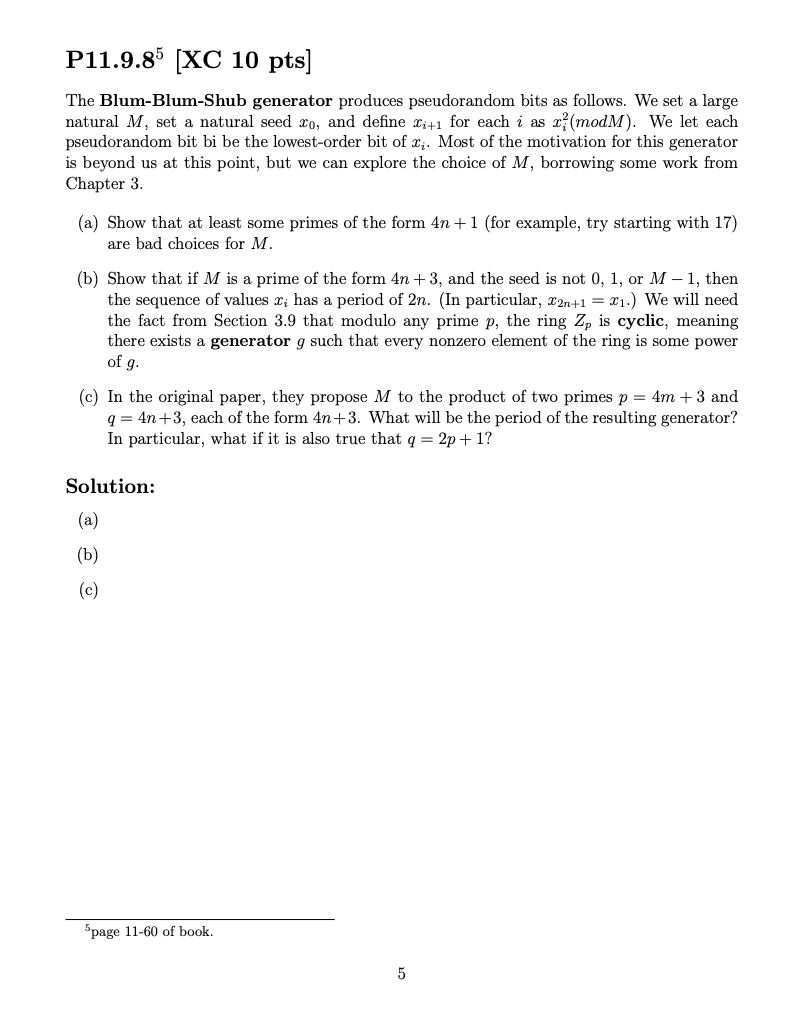

P11.9.85 [XC 10 pts] The Blum-Blum-Shub generator produces pseudorandom bits as follows. We set a large natural M, set a natural seed ro, and define rit1 for each i as x? (modM). We let each pseudorandom bit bi be the lowest-order bit of ;. Most of the motivation for this generator is beyond us at this point, but we can explore the choice of M, borrowing some work from Chapter 3. (a) Show that at least some primes of the form 4n + 1 (for example, try starting with 17) are bad choices for M. (b) Show that if M is a prime of the form 4n + 3, and the seed is not 0, 1, or M - 1, then the sequence of values r, has a period of 2n. (In particular, Tan+1 = 21.) We will need the fact from Section 3.9 that modulo any prime p, the ring Z, is cyclic, meaning there exists a generator g such that every nonzero element of the ring is some power of g. (c) In the original paper, they propose M to the product of two primes p = 4m + 3 and q = 4n +3, each of the form 4n + 3. What will be the period of the resulting generator? In particular, what if it is also true that q = 2p + 1? Solution: (a) (b) (c) Spage 11-60 of book. 511.9 Pseudorandom Generators 11.9.1 Generators and Seeds Random numbers are computationally useful. In an algorithms course you'll learn that Quicksort, the fastest known general sorting algorithm in terms of average-case running time, makes random choices of "pivot elements", at least in the version that is usually presented. A computer game or any program that simulates reality may want to make random choices to represent those not under a player's control, or to explore the range of things that may happen, as we'll see in the following section. There are some mathematical problems, such as testing large integers for primality, where some of the best algorithms known make random choices. And in cryptography, as we saw in Section 3.11, the one-time pad depends for its security guarantee on the fact that every possible message of a given length is equally likely to be sent. But the problem with true random numbers is that they are expensive. We can produce random bits, or digits, or small integers, or small sets, by the mechanical means that have been the subject of much of our probabilistic analysis - coins, dice, or cards. If we interrupt a stopwatch that measures hundredths of a second, the lowest-order digit of the time is a fairly uniformly random digit. But these methods don't scale easily to produce the numbers of random bits that could be used at the rate that an electronic computer might want them. We could look at the system clock of the computer, but quite a lot might happen in the next millisecond or even microsecond until that clock changes its reading. A physical process - counting the number of radioactive decays observed in a tiny time interval, for example - might be faster than coins or dice but still not up to the speed of the computer. The solution to this problem is to sacrifice true randomness to speed and cheapness by using a pseudorandom generator. We design a function f that takes bit strings of a given length to other bit strings of the same length, such that there is no easily observable pattern in which strings go to which. Then we take an initial string w, called the seed, and let our pseudorandom sequence of bits be the concatenation of the strings w, f(w), f(f(w)), f3(w), f(w), and so forth. The function f is deterministic, so the sequence of strings must eventually revisit the same string, whereupon it will repeat itself forever, unlike a true random string. But we can hope that if we choose f well, the period or length of the sequence of strings between reoccurrences will be long. And the fact that the entire sequence is determined by the original seed can have its advantages as well - unlike a truly random sequence, a pseudorandom sequence could be reproduced by someone else who wanted to check our work, if we just give them the seed we used.The solution to this problem is to sacrifice true randomness to speed and cheapness by using a pseudorandom generator. We design a function f that takes bit strings of a given length to other bit strings of the same length, such that there is no easily observable pattern in which strings go to which. Then we take an initial string w, called the seed, and let our pseudorandom sequence of bits be the concatenation of the strings w, f(w), f(f(w)), f3(w), f(w), and so forth. The function f is deterministic, so the sequence of strings must eventually revisit the same string, whereupon it will repeat itself forever, unlike a true random string. But we can hope that if we choose f well, the period or length of the sequence of strings between reoccurrences will be long. And the fact that the entire sequence is determined by the original seed can have its advantages as well - unlike a truly random sequence, a pseudorandom sequence could be reproduced by someone else who wanted to check our work, if we just give them the seed we used. Of course a deterministically generated sequence cannot be truly random. There are bound to be relations among the strings, and the question is whether these relations interfere with the purpose to which the pseudorandom numbers are being put. If there is a w such that f(w) = w, for example, and the sequence reaches this fixed point, this is probably very bad because we will keep using the same bits over and over again. If the sequence gets stuck with a short period, we try only a few of the possible strings no matter how long we extend the sequence. We probably don't want all of, or even most of, the strings in our sequence to have the same first bit, or the same last bit, or to fail any obvious sort of statistical test. And if we are using the sequence for cryptography, we can't even afford to have our enemy determine how we are producing the sequence, because they thenmight be able to reproduce it. The difference between true randomness and pseudorandomness can show up in surprising ways. The designers of the early computer arcade game Space Invaders could not afford a real random number generator given their very tight resource constraints, so they used the player's actions as their source of "randomness" - a flying saucer shows up the 22nd time the player fires her cannon and again every 15 shots thereafter. Experienced players soon discovered and exploited this pattern. The designers of the C language's sorting program didn't have time to choose a pivot element randomly when they implemented Quicksort, so they chose the median of three particular elements. Programming guru Jon Bentley found that this choice brought out the worst- case behavior of Quicksort in some perfectly plausible types of input 24. 11.9.2 The Linear Congruential Generator One of the first pseudorandom generators developed was the middle-square function of John von Neumann. He reasoned that if you took a long number and squared it, the high-order and low-order bits of the result might depend in a simple way on the input number, but the middle bits would depend on it in a complicated way that might appear fairly random. We'll play with this generator in the Exercises and Problems. As it turns out, the middle-square function was soon supplanted by another idea that used something like the same reasoning. If I take a non-integer and multiply it by a very large integer, it stands to reason that the fractional part of the result might be equally likely to fall anywhere between zero and one, unless of course the input were a fraction with a small denominator. But if I start with a random seed somewhere between zero and one, the chance of getting such an unusual number is small. The linear congruential generator implements this idea, except that it works with integers rather than with floating point numbers. (The latter use approximations of large numbers that might get us into trouble - see Exercise 11.9.5) We choose a modulus m and define our function f to map the set of integers modulo m into itself. As the name implies, f is just a linear function modulo m: f(x) = (ax + c) om, where "%" is the Java modular division operator. Usually we take m to be a power of two, so that the integers modulo m are just bit strings of the appropriate length. We want a to be relatively prime to m, which is true whenever a is odd and m is a power of two. The choice of a and c can be more complicated, and a great deal of empirical work has gone into investigating the periodicity of f using various choices, leading to those used today.Pseudorandom Generators: Definition . So, in the real world of computing, we normally get pseudorandom numbers in order to produce then on an industrial scale. . We design a function f that takes bit strings of a given length to other bit strings of the same length, such that there is no observable pattern in which strings go to which. . Then we take an initial string w, called the seed, and let our sequence of pseudorandom bits be the concatenation of w, f(w), f(f(w)), f3 (w), f4(w) ,... Pseudorandom Generators: Definition . Because the function is deterministic, and there are only finitely many strings of that length, the sequence must eventually repeat. We can hope that the period is long enough. . There's actually an advantage in having future strings be determined from the first one - unlike a truly random sequence, someone else can check our work if we give them the seed. Pseudorandom Generators: Definition . There are perhaps surprisingly many situations when the difference between pseudorandom and random bits makes a difference. . The arcade game Space Invaders used the player's moves as their source of "randomness", and players figured out how to exploit this. . The commercial version of Quicksort, choosing a pivot pseudorandomly, ran very slowly on a class of plausible inputs, as Jon Bentley showed

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts