Question: In the case study, When to Walk Away from a Deal , the authors discuss the Map of Synergies (see image below). Based on your

In the case study, When to Walk Away from a Deal, the authors discuss the Map of Synergies (see image below). Based on your reading of the case study, why are functions that are duplicated (see below Functions Duplicated) listed under a short time frame but with high probability of success? What does that mean?

In the case study, When to Walk Away from a Deal, the authors discuss the Map of Synergies (see image below). Based on your reading of the case study, why are functions that are duplicated (see below Functions Duplicated) listed under a short time frame but with high probability of success? What does that mean?

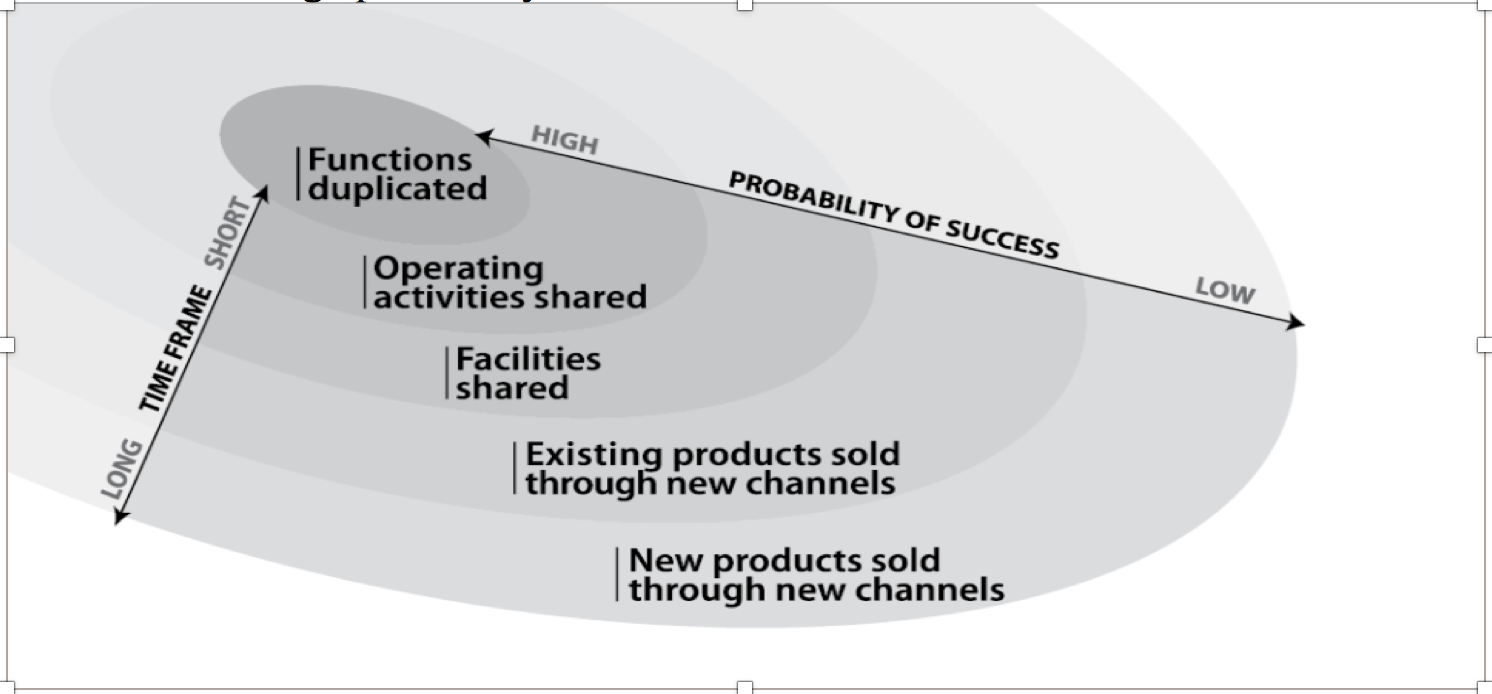

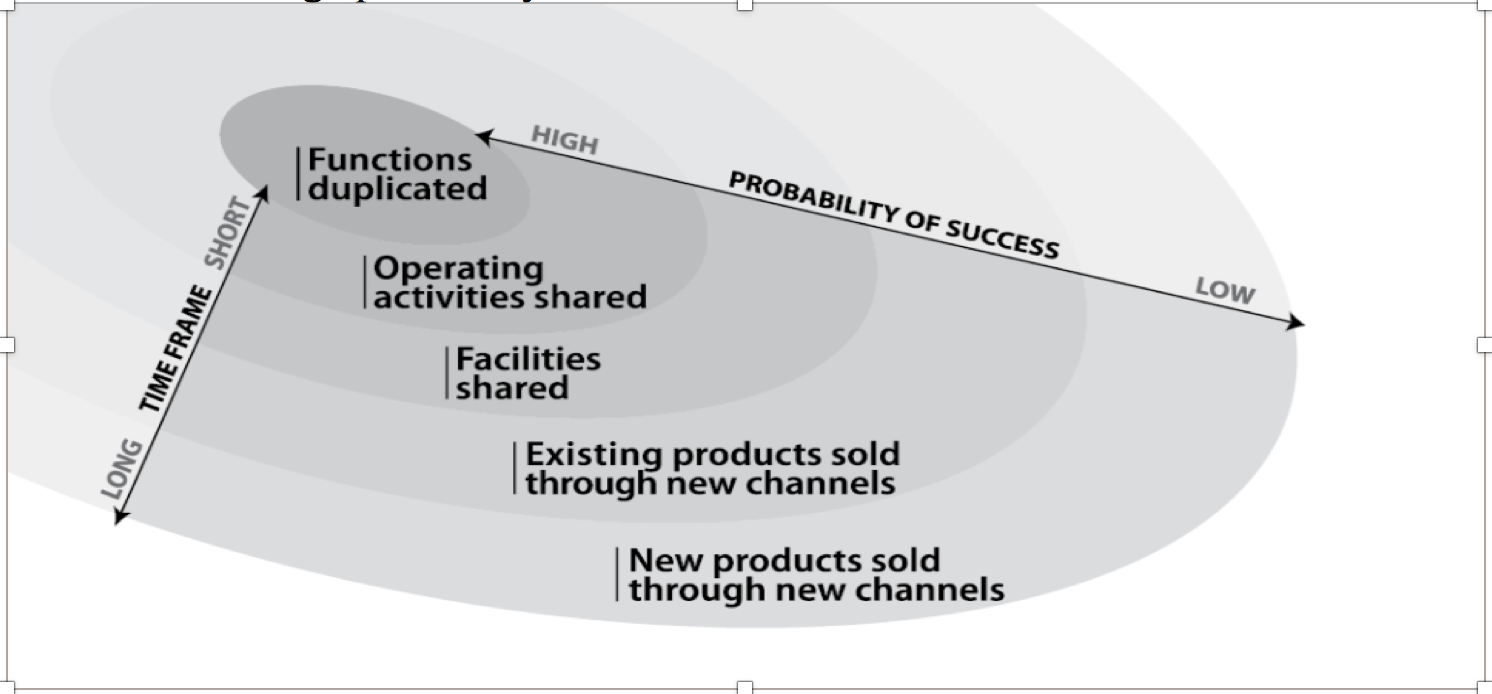

took pains to explain to Odeon's executives that a deep understanding of Odeon's busi- ness would help ensure the ultimate success of the merger. Cinven and Odeon executives worked as a team to examine the results of each cinema and to test the assumptions of Odeon's business model. They held four day- long meetings in which they went through each of the sites and agreed on the most im- portant levers for revenue and profit growth in the local markets. Although the process may strike the target company as excessively intrusive, target managers will find there are a number of benefits to going along with it beyond pleasing a potential acquirer. Even if the deal with Cinven had fallen apart, Odeon would have emerged from the deal's due diligence process with a much better under- standing of its own economics. Of course, no matter how friendly the ap- proach, many targets will be prickly. The com- pany may have something to hide. Or the target's managers may just want to retain their independence; people who believe that knowledge is power naturally like to hold on to that knowledge. But innocent or not, a target's hesitancy or outright hostility during due diligence is a sign that a deal's value will be more difficult to realize than originally expected. As Joe Trustey, managing partner of private equity firm Summit Partners, says: "We walk away from a target whose manage- ment is uncooperative in due diligence. For us, that's a deal breaker." companies away from smart acquisitions. A better approach is to use the due diligence process to carefully distinguish between dif- ferent kinds of synergies, and then estimate both their potential value and the probability that they can be realized. That assessment should also include the speed with which the synergies can be achieved and the invest- ments it will take to get them. We've found it useful to think of potential synergies as a series of concentric circles, as shown in the exhibit, A Map of Synergies." The synergies at the center come from elimi- nating duplicate functions, business activities, and costs for instance, combining legal staffs, treasury oversight, and board expenses. These are the easiest synergies to achieve; compa- nies are sure to realize most of the potential savings here. The next closest circle repre- sents the savings realized from cutting shared operating costs, such as distribution, sales, and regional overhead expenses. Most compa- nies will realize the majority of these savings, as well. Then come the savings from facilities rationalization, which are typically more difficult to achieve because they can involve significant personnel and regulatory issues. Farther out are the more elusive revenue synergies, starting with sales of existing prod- ucts through new channels and moving to the outermost circle, selling new products through new channels. Each circle offers large rewards, but the farther out the savings or revenues lie, the more difficult they become to achieve and the longer it will take. Catego- rizing synergies in this way provides a useful framework for valuing them. Analysts can assign to each circle a potential value, a prob- ability for achieving the value, and a time- table for implementation, which can be used to model the synergies' effect on the combined cash flows of the companies. It's important that this analysis also ex- plicitly consider the cost of achieving the synergies, in both cash and time. In one dra- matic case, the Canadian real estate compa- nies O&Y Properties and Bentall Capital called off their planned merger in 2003 after tallying up the integration costs neces- sary to realize the synergies. O&Y managed properties throughout eastern Canada, while Bentall's holdings were concentrated in the West. In addition to complementing each other geographically, the two companies be- Where Are the Synergiesand the Skeletons? It's hard to be realistic about the synergies an acquisition will deliver. In the fevered envi- ronment of a takeover, managers routinely overestimate the value of cost and revenue synergies and underestimate the difficulty of achieving them. It's worth repeating that two- thirds of the executives in our M&A survey admitted to having overestimated the syner- gies available from combining companies. Realizing that synergy estimates are often untrustworthy, some companies have made it their policy not to take potential synergies into account when determining the value of acquisition candidates. Although the concern behind the policy is understandable, such an approach can be destructive: Some synergies are achievable, and ignoring them may steer When to Walk Away from a Deal lieved they could rationalize expenses over a larger collection of properties and still have representatives on the ground in every major North American city. Yet, after due diligence, both sides realized that the high costs of inte- gration would likely overwhelm any long-run savings and revenue gains. Bentall president Gary Whitelaw told the press that his com- pany had grown "increasingly concerned that the scale of the integration could divert resources away from our primary objec- tive....The merger risks would have been sig- nificant, demanding increased management attention, and resulting in larger integration costs than at first may have been thought." The deal was scuttled, to the benefit of O&Y's and Bentall's shareholders. It is perhaps understandable that managers might want to put off thinking about the sen- sitive issues inherent in integration planning until after the deal is signed and sealed. But that often a serious mistake. Integration planningand the costs of integration-are among the biggest determinants of an acqui- sition's ultimate success or failure, and you can't really declare a due diligence process complete unless you've looked closely at those costs. The due diligence team's deep knowledge of the acquisition target makes it an ideal body to develop an initial road map for combining two companies' staffs and operations. In addition to examining the cost of achiev- ing positive synergies, the due diligence team also needs to consider how potential conflicts between the merged businesses may sap reve- nues or add costs. These negative synergies the skeletons in the closet of every deal-can take many forms. Once two companies com- bine their accounts, for example, some of their joint customers may curtail their pur- chases for fear of being overly reliant on a single supplier. Difficulties in integrating back-office operations or systems may at least A Map of Synergies A deal's potential synergies are best viewed as a series of concentric circles. Those close to the center tend to be cost-saving synergies, which can be realized quickly and are likely to succeed. Those on the outside are revenue generating synergies, which require a lot of time and man- agement and are less likely to succeed. In determining your walk-away price, your discount factor for synergies should rise as you move away from the center HIGH Functions I duplicated PROBABILITY OF SUCCESS LOW LONG TIME FRAME Operating, lactivities shared Facilities shared Existing products sold I through new channels New products sold through new channels briefly impede customer service and order fulfillment, leading to a loss of sales. Seeing more competition for promotions, talented employees may leave, sometimes taking customers with them. And the inevitable distractions of a merger may force manage- ment to pay less attention to the core busi- ness, undermining its results. Despite their often immense importance, negative syner- gies are routinely overlooked in due diligence. A common mistake, for example, is to create a valuation model that adds up the revenues of the two companies, plus the synergies, without subtracting an estimated amount for revenue erosion or increased costs. Even the best acquirers will encounter negative synergies. An executive who left cereal giant Kellogg after its 2001 merger with biscuit maker Keebler told us that the com- pany experienced negative synergies when it decided to put new-product launches on hold in order to focus on integrating the two com- panies. Some potential revenues were lost as a result even though Kellogg met its targets for cost reductions. A more devastating exam- ple of negative synergies occurred in the 1996 merger of the Southern Pacific and the Union Pacific railroads. Incompatibilities in the com- panies' information systems, combined with other operating conflicts, created massive dis- ruptions in rail traffic throughout the western United States, leading to delayed and mis- routed shipments and irate customers. In the end, the government had to declare a federal transportation emergency. Even though this was a deal that we desperately wanted, I conditioned myself mentally to say we might not have it." -Kellogg CEO Carlos Gutierrez purchase of Keebler. Gutierrez dearly wanted to close the deal. Keebler's vaunted direct- to-store delivery system enabled it to carry products to stores in its own trucks, bypassing the retailers' warehouses altogether. Gutier- rez saw enormous potential for funneling Kellogg products through Keebler's highly efficient system. But Kellogg's rigorous due diligence analysis made it clear that the maxi- mum he should pay for Keebler was $42 a share, which he expected was less than what Keebler was looking for. "Even though this was a deal that we desperately wanted," Gutierrez later recalled, "I conditioned myself mentally to say we might not have it." In a final bargaining session in New York, Gutier- rez told Keebler's management that a share price of $42 was his maximum offer-and that if they could get more from some- one else, they should take it. Gutierrez went off to watch a Mets game, determined not to give any more thought to the negotiation. Two days later, Keebler accepted Gutierrez's offer. To establish a walk-away price, successful deal makers convene a decision-making body of trusted individuals who are less attached to the deal than senior management is. They insist on senior management's approval of the body and establish a decision-making process that clearly delineates who in the company recommends deals, who holds veto power, whose input should be solicited, and who decides yes or nay in the final instance. They adopt formal checks and balances that rely on predetermined walk-away criteria. Bridgepoint assembles a team of six manag- ers, each of whom represents one of four viewpoints. One is the prosecutor, who plays the role of devil's advocate. The second is the less-experienced manager, whose involvement is a key part of his or her training. The third is a senior managing director, who no longer has any hierarchical function at the company and who therefore cannot be undermined by corporate politics. The final members of the panel are managing directors who still have operational roles. The team's goal is to pro- vide a thorough, balanced, and unbiased ex- amination of the acquisition candidate and hold everyone's feet to the fire on walk-away criteria. "That makes quite a balanced whole," says Bridgepoint's Bassi. "Is it perfect? I don't know. But it works." What's Our Walk-Away Price? The final leg of a sound due diligence process is determining a walk-away pricethe top price you are willing to pay when the final price negotiation is conducted. The walk-away price should never include the full potential value of the synergies, which is why it's important to calculate the deal's stand-alone value separately. Synergies- especially the elusive outer-circle synergies are something that you target in managing a completed acquisition; they should not unduly influence the negotiation of the deal unless you can be fairly certain about the numbers. For a walk-away price to have meaning, you really have to be willing to walk away. A use- ful lesson in that regard comes from Kellogg's CEO, Carlos Gutierrez, who negotiated the HIGH Functions duplicated PROBABILITY OF SUCCESS LOW TIME FRAME SHORT Operating activities shared Facilities shared LONG Existing products sold through new channels New products sold through new channels

In the case study, When to Walk Away from a Deal, the authors discuss the Map of Synergies (see image below). Based on your reading of the case study, why are functions that are duplicated (see below Functions Duplicated) listed under a short time frame but with high probability of success? What does that mean?

In the case study, When to Walk Away from a Deal, the authors discuss the Map of Synergies (see image below). Based on your reading of the case study, why are functions that are duplicated (see below Functions Duplicated) listed under a short time frame but with high probability of success? What does that mean?