Question: please answer question 2 The artists who come to us often have no idea what it is like to be part of an organization like

please answer question 2

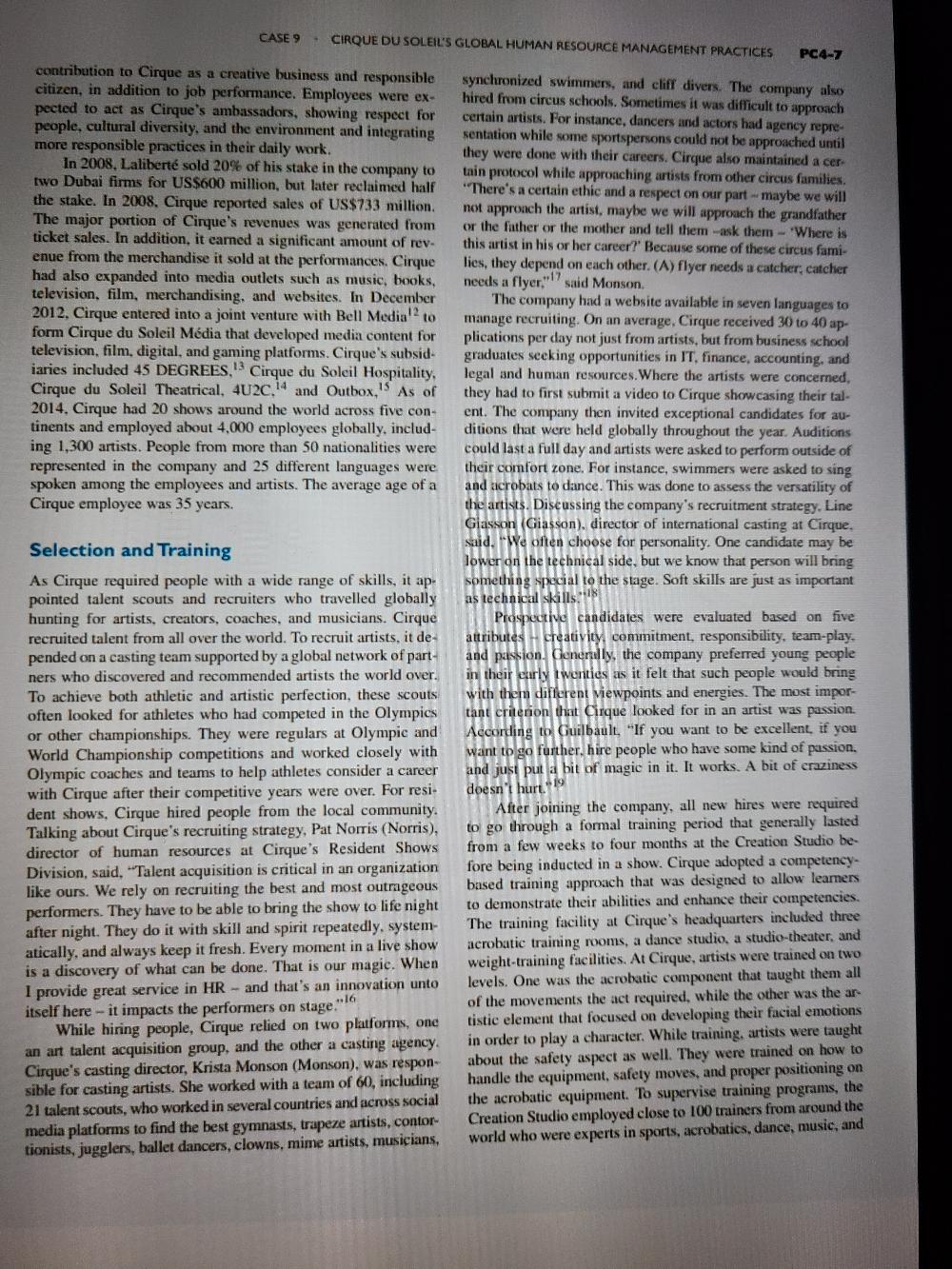

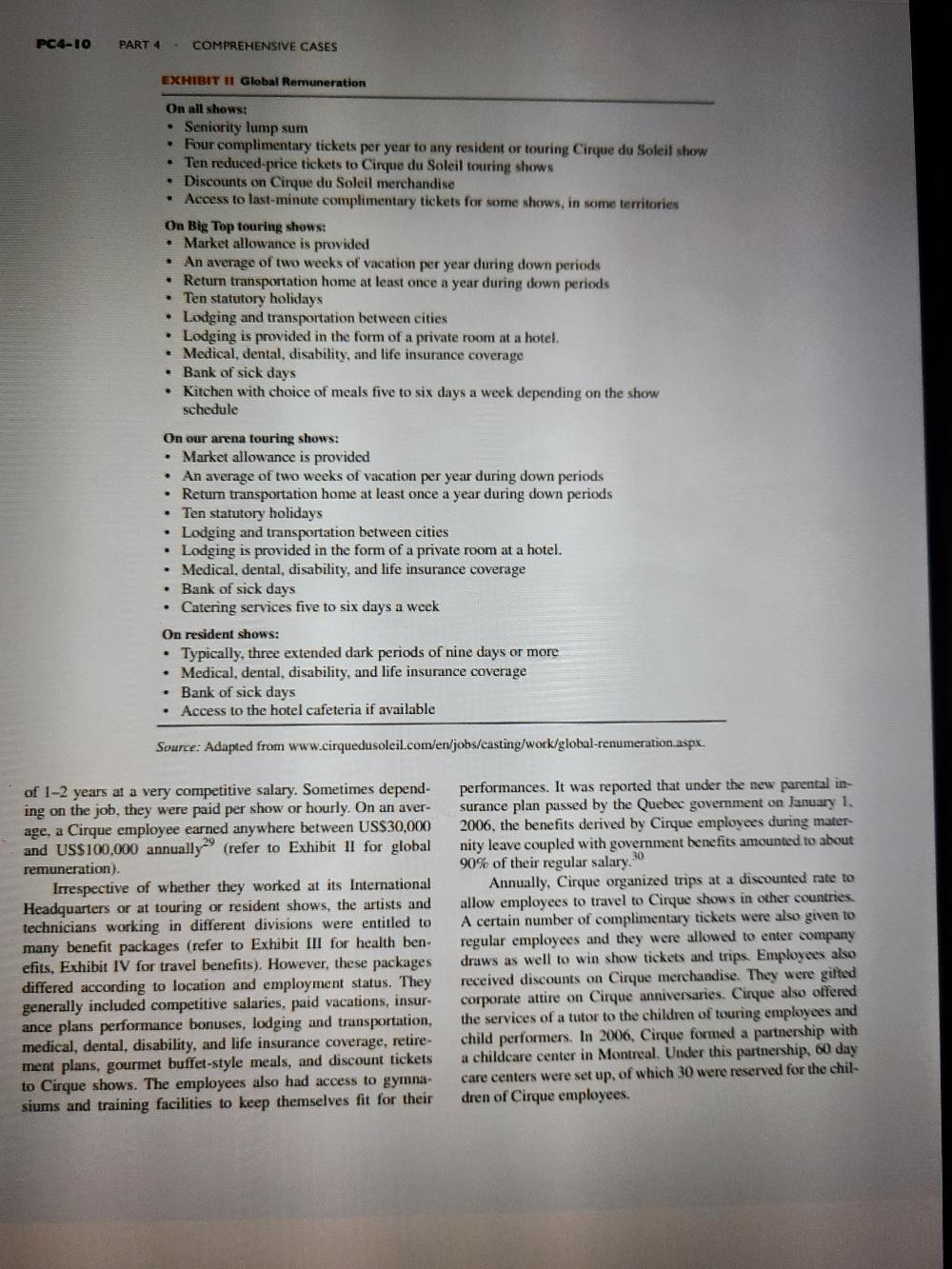

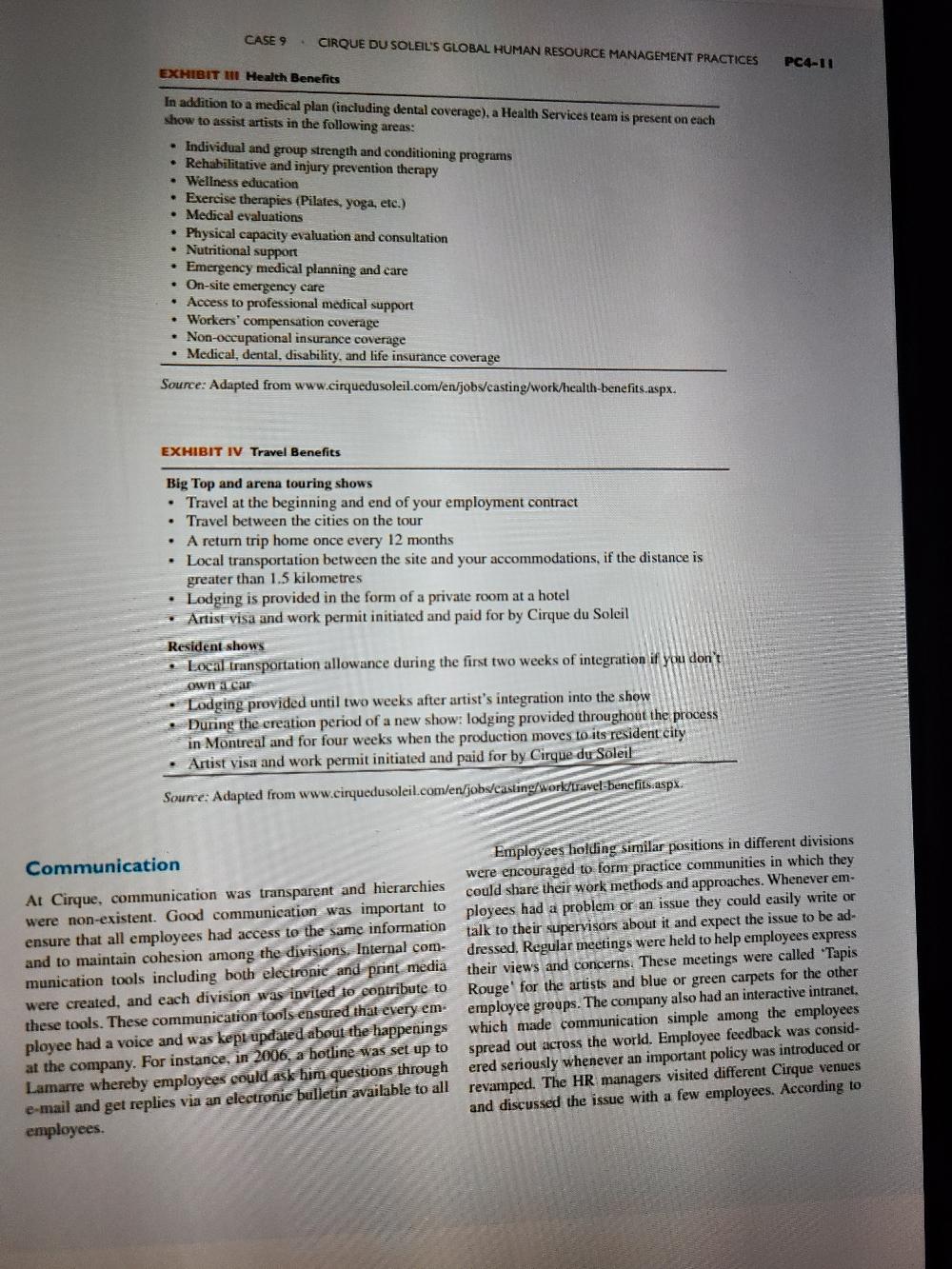

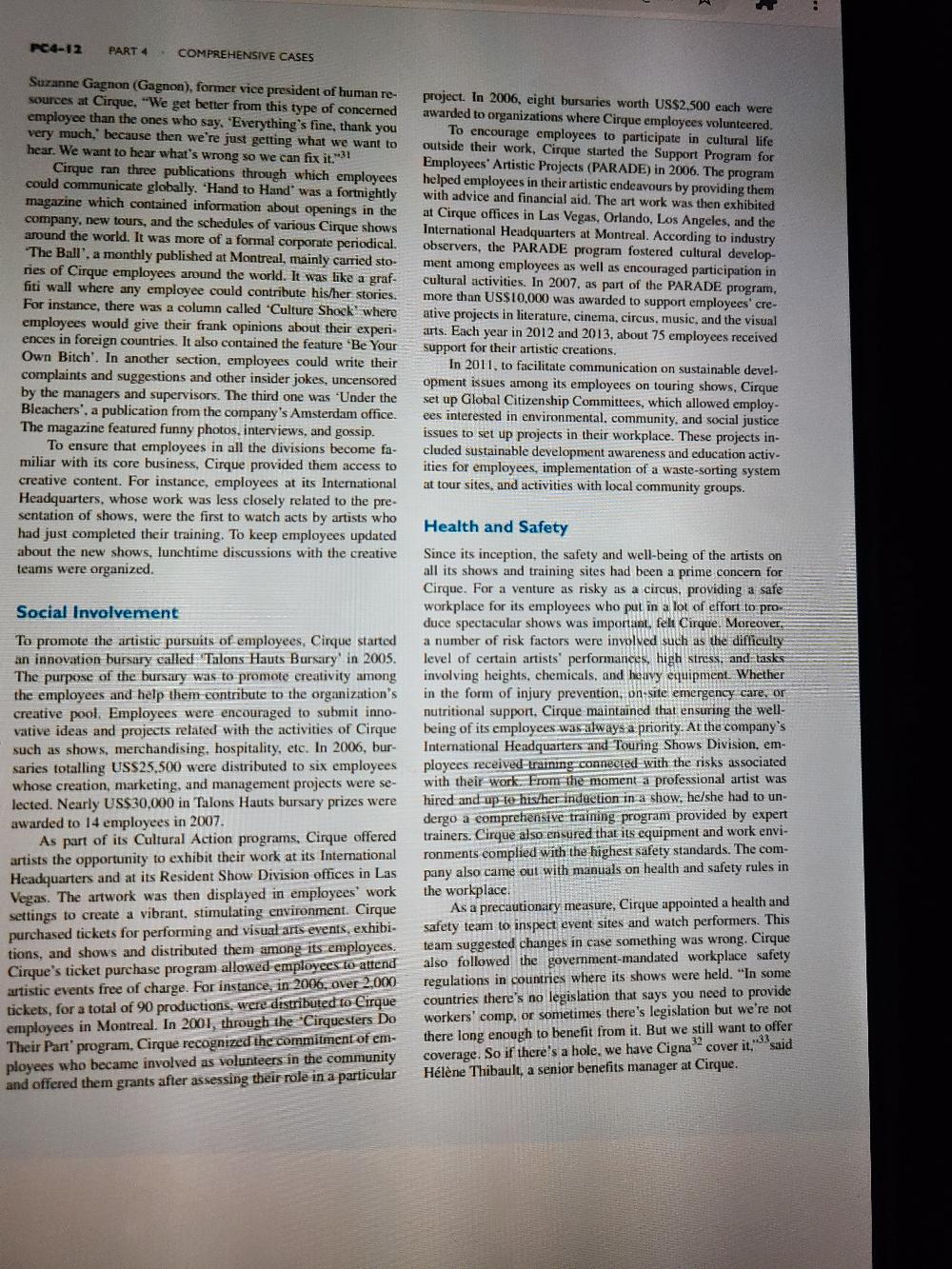

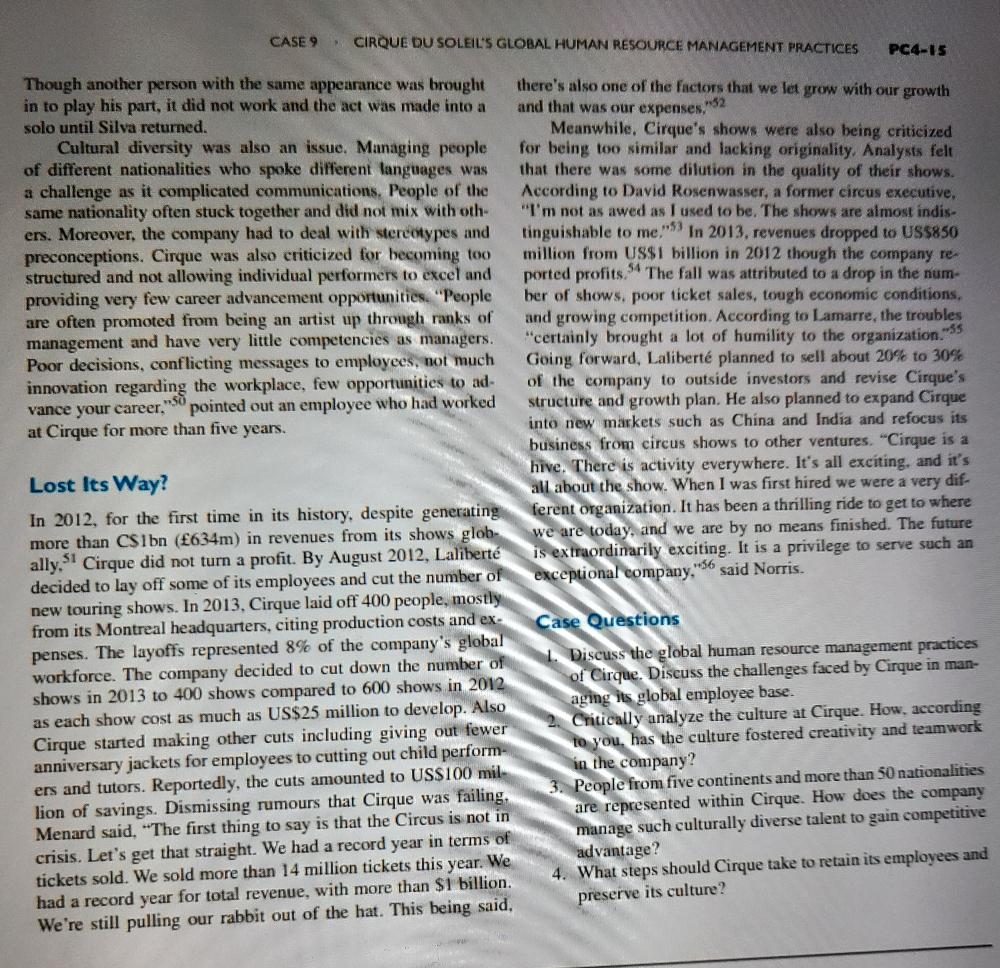

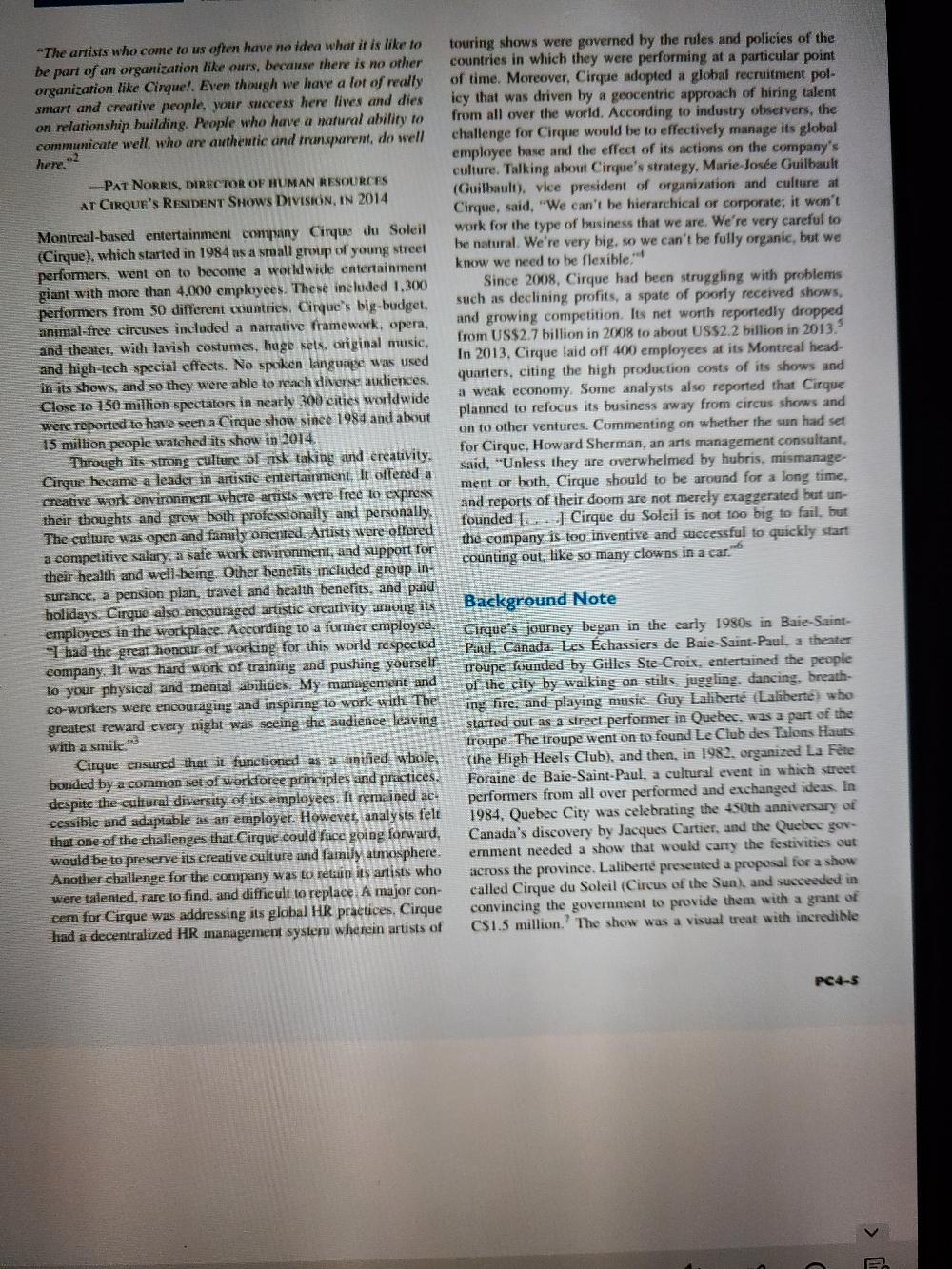

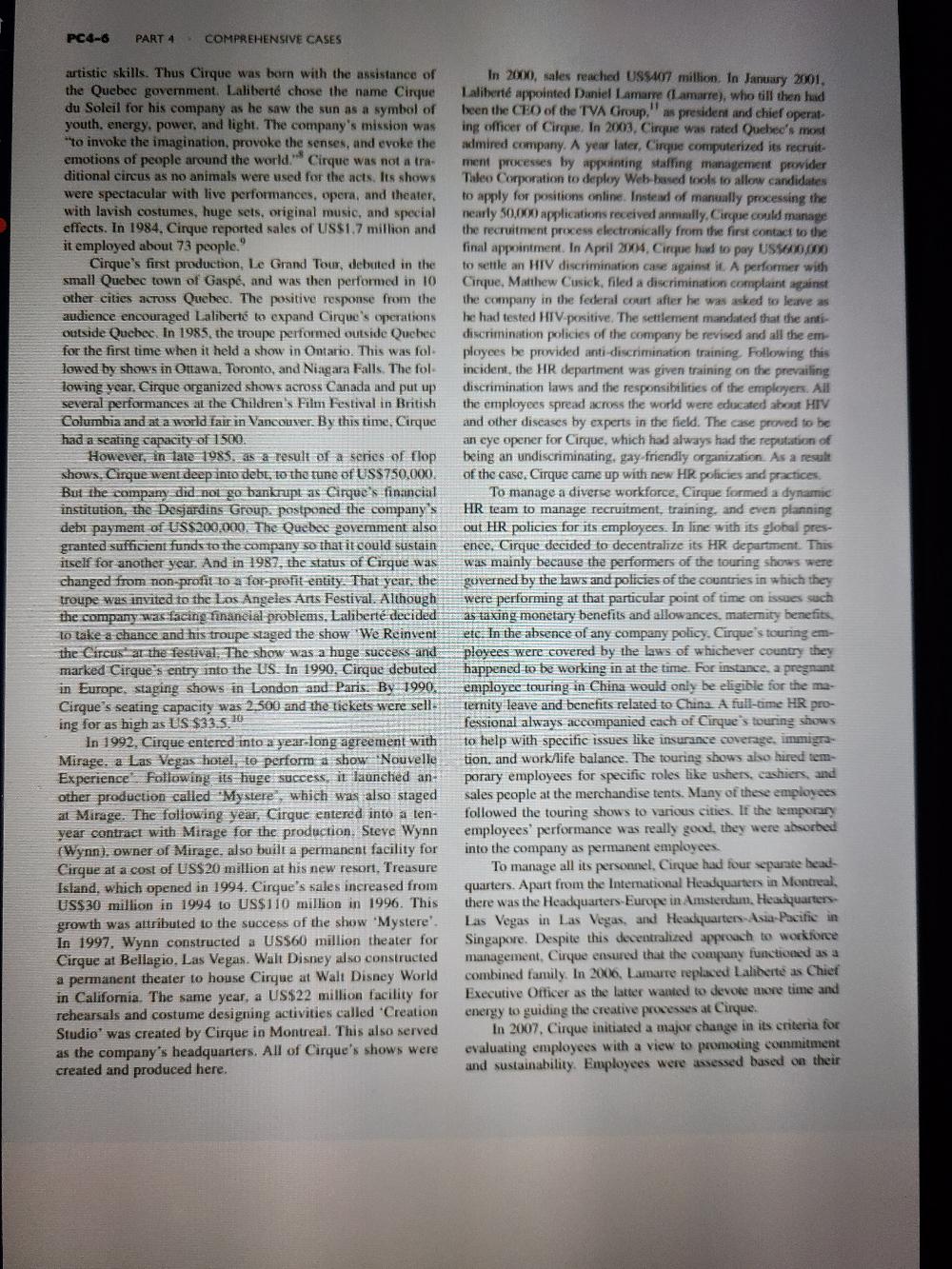

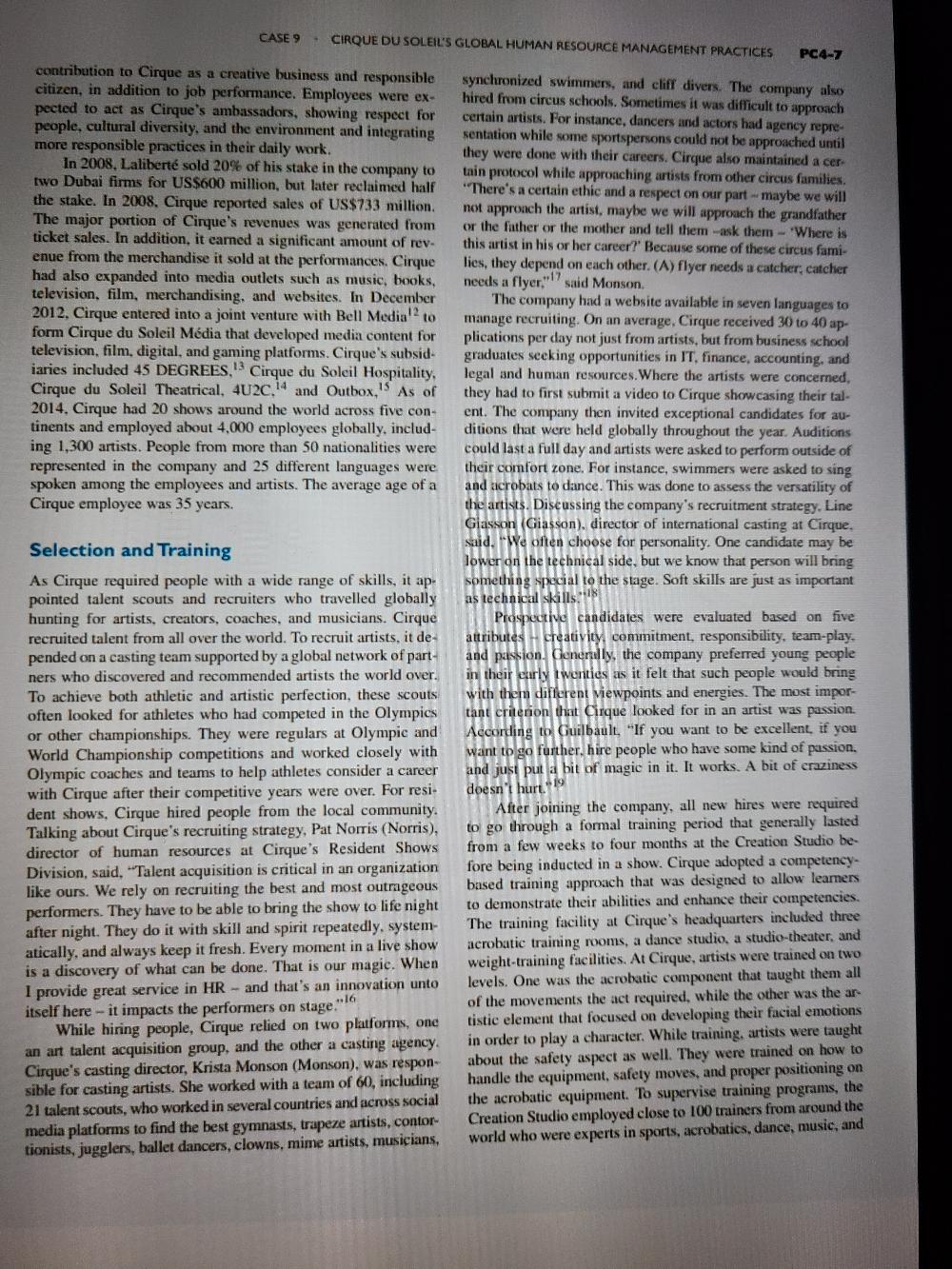

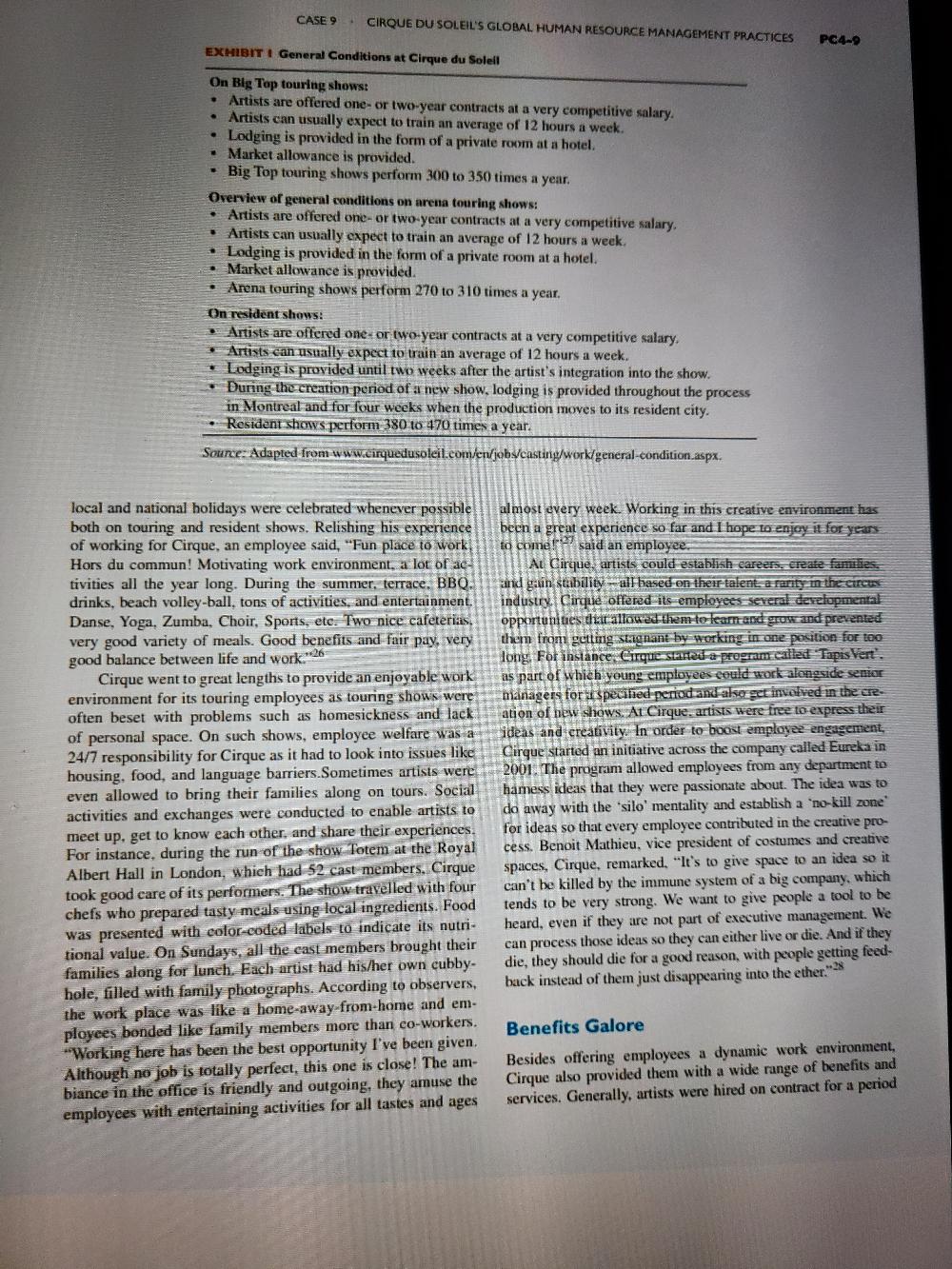

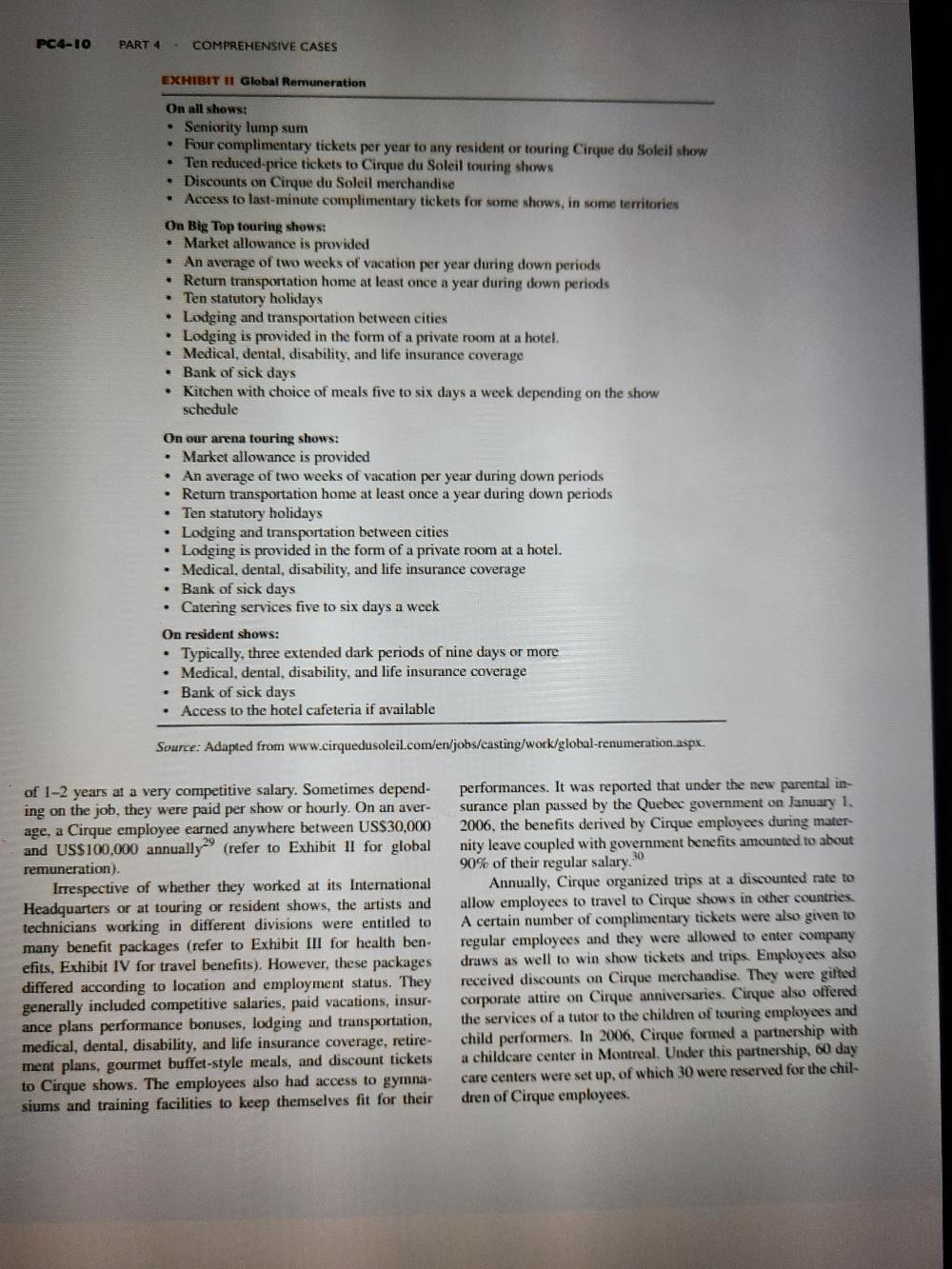

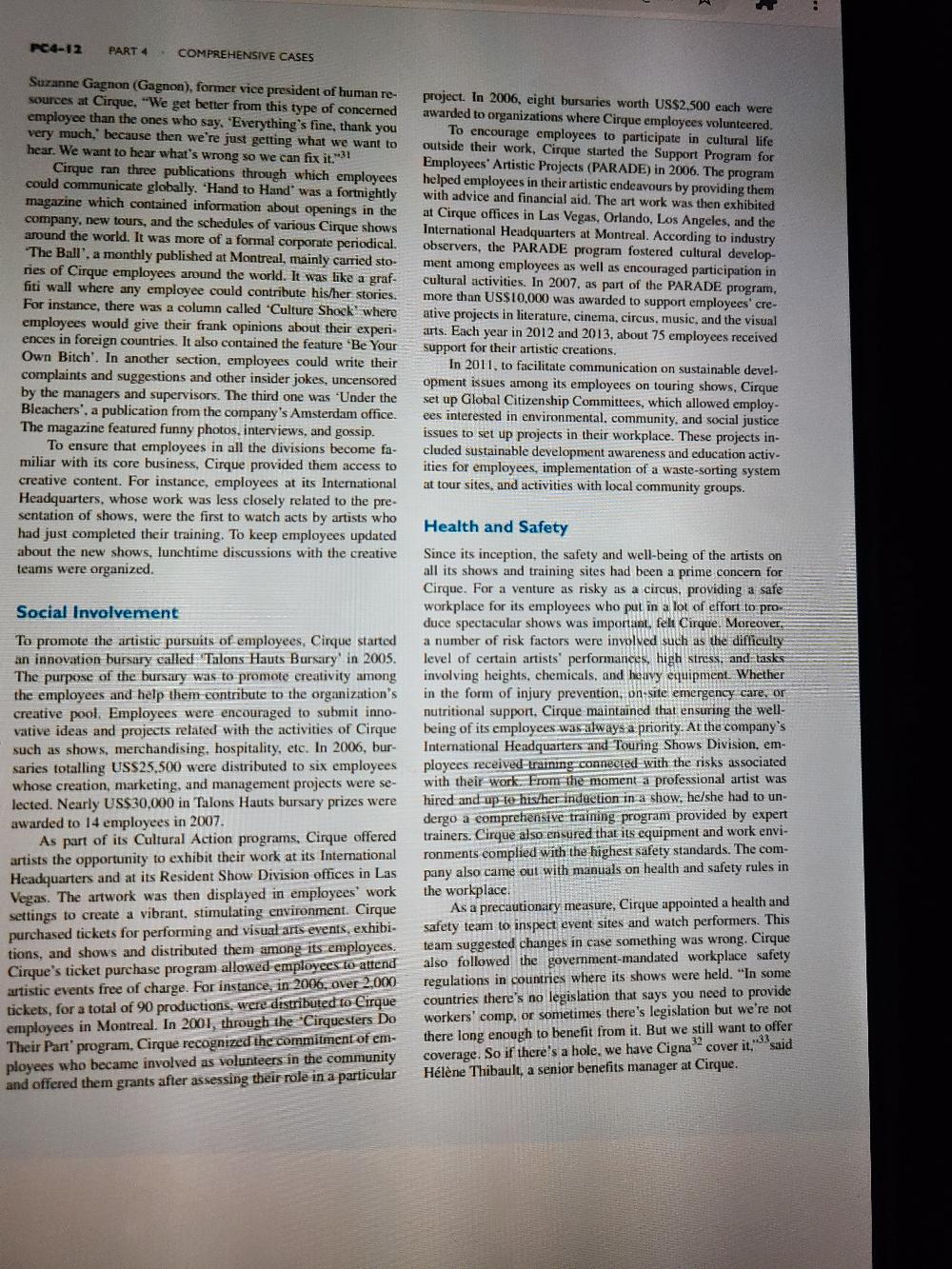

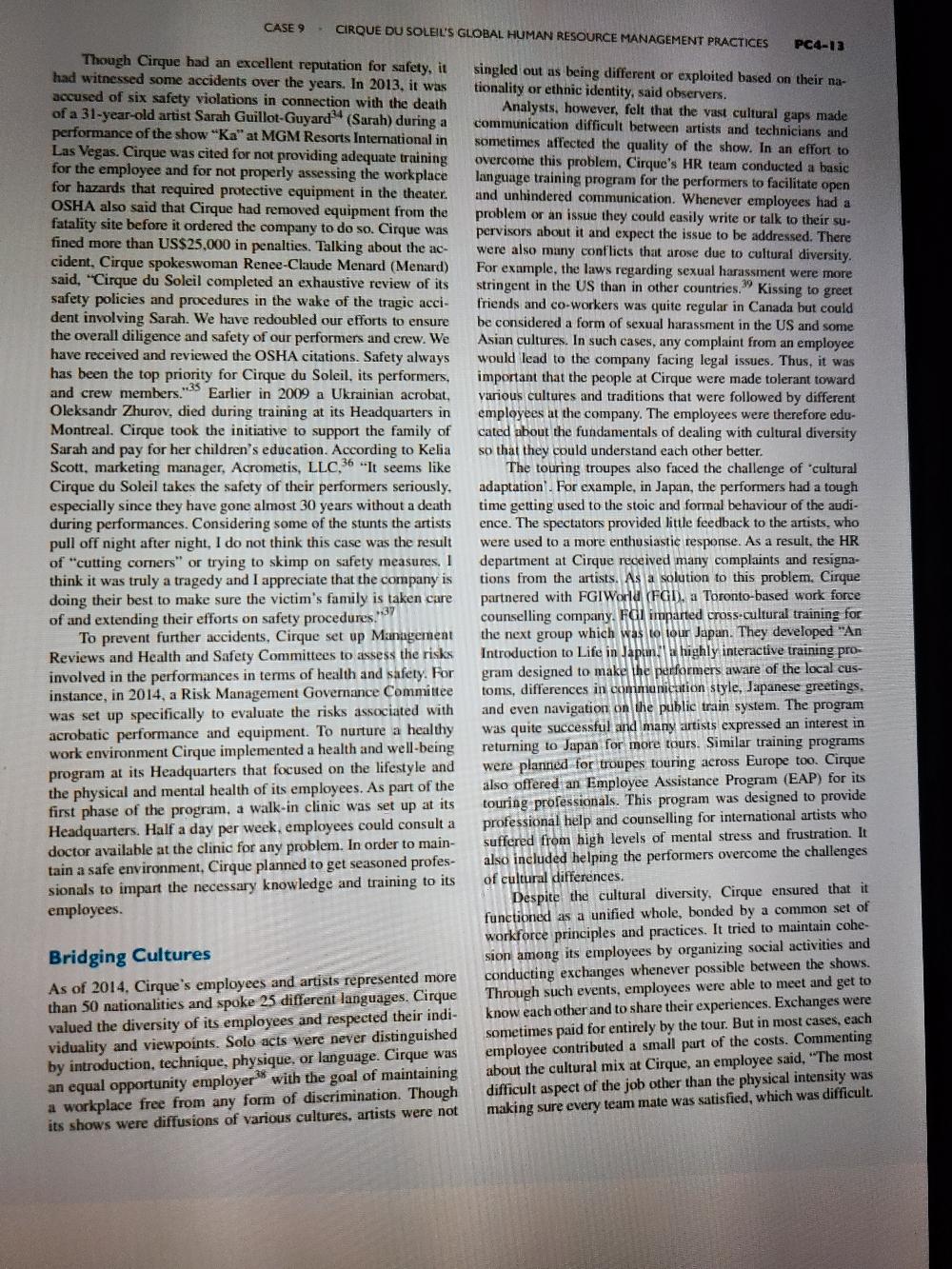

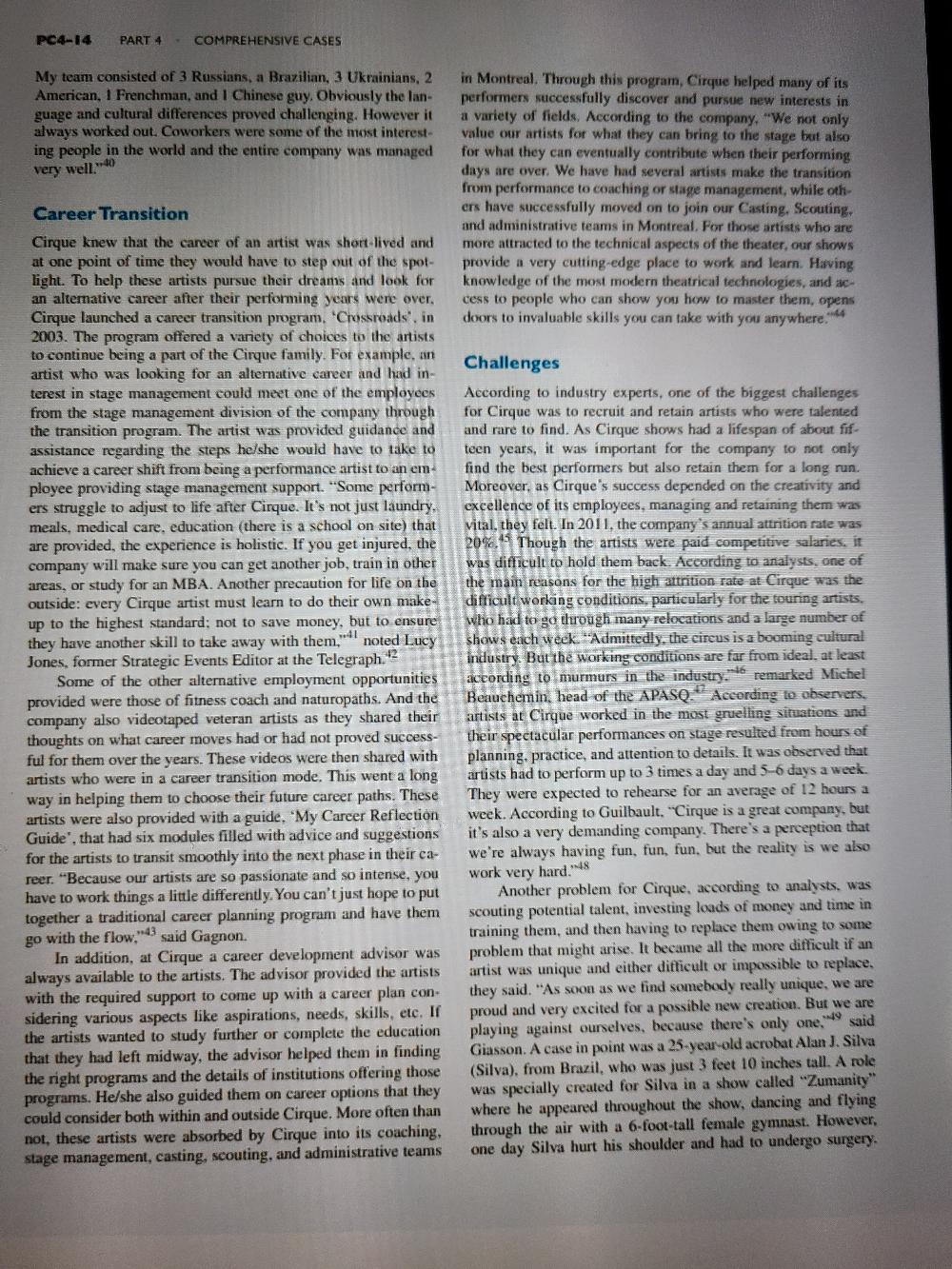

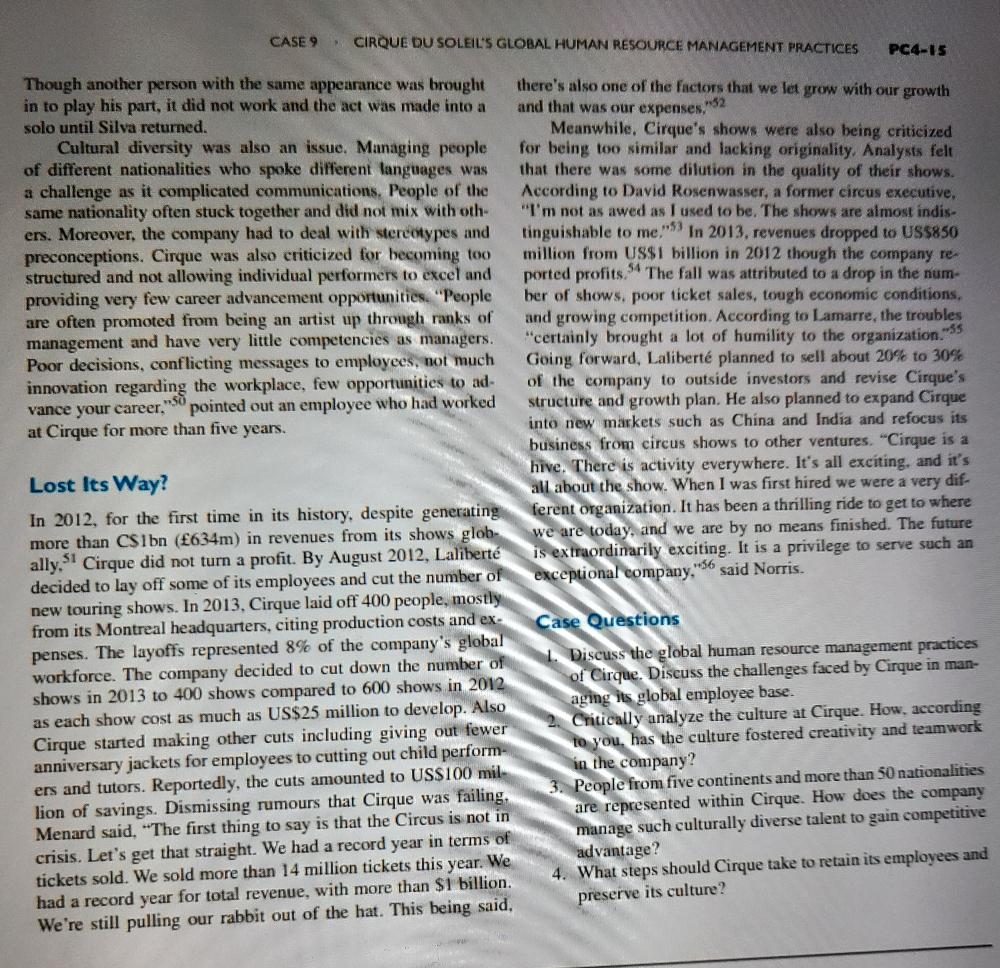

"The artists who come to us often have no idea what it is like to be part of an organization like ours, because there is no other organization like Cirque!. Even though we have a lot of really smart and creative people, your success here lives and dies on relationship building. People who have a natural ability to communicate well, who are authentic and transparent, do well here. 2 PAT NORRIS, DIRECTOR OF HUMAN RESOURCES AT CIRQUE'S RESIDENT SHOWS DIVISION, IN 2014 Montreal-based entertainment company Cirque du Soleil (Cinque), which started in 1984 as a small group of young street performers, went on to become a worldwide entertainment giant with more than 4,000 employees. These ineluded 1.300 performers from 50 different countries. Cinque's big-budget, animal-free cireuses included a narrative framework, opera, and theater, with lavish costumes, hage sets, original music, and high-tech special effects. No spoken language was used in its shows, and so they were able to reach diverse audiences. Close to 150 million spectators in nearly 300 cities worldwide were reported to have seen a Cinque show since 1984 and about 15 million people watched its show in 2014, Through its strong culture of risk taking and creativity. Cirque became a leader in artistic entertainment, It offered a creative work environment where artists were free to express their thoughts and grow both professionally and personally, The culture was open and famly oncied. Artists were offered a competitive salary, a safe work environment, and support for their health and well-being Other henefits included group in- surance, a pension plan, travel and health benefits, and paid holidays. Cirque also encouraged artistic creativity among its employees in the workplace. According to a former employee. had the great honour of working for this world respected company. It was hard work of training and pushing yourself to your physical and mental abilities. My management and co-workers were encouraging and inspiring to work with The greatest reward every night was seeing the audience leaving with a smile Cirque ensured that it functioned as a unified whole, bonded by a common set of workforee principles and practices, despite the cultural diversity of its employees. It remained ac cessible and adaptable as an employer. However, analysts feli that one of the challenges that Cirque could face going forward, would be to preserve its creative culture and family atmosphere. Another challenge for the company was to retain its antists who were talented, rare to find, and difficult to replace A major con- cem for Cirque was addressing its global HR practices, Cirque had a decentralized HR management syster wherein artists of touring shows were governed by the rules and policies of the countries in which they were performing at a particular point of time. Moreover, Cirque adopted a global recruitment pol- icy that was driven by a geocentric approach of hiring talent from all over the world. According to industry observers, the challenge for Cirque would be to effectively manage its global employee base and the effect of its actions on the company's culture. Talking about Cirque's strategy, Marie-Jose Guilbault (Guilbault), vice president of organization and culture at Cirque, said. "We can't be hierarchical or corporate; it won't work for the type of business that we are. We're very careful to be natural. We're very big, so we can't be fully organic, but we know we need to be flexible Since 2008, Cirque had been struggling with problems such as declining profits, a spate of poorly received shows, and growing competition. Its net worth reportedly dropped from US$2.7 billion in 2008 to about US$2.2 billion in 2013. In 2013, Cirque laid off 400 employees at its Montreal head- quarters, citing the high production costs of its shows and a weak economy. Some analysts also reported that Cirque planned to refocus its business away from circus shows and on to other ventures. Commenting on whether the sun had set for Cirque, Howard Sherman, an arts management consultant said, "Unless they are overwhelmed by hubris, mismanage- ment or both, Cirque should to be around for a long time, and reports of their doom are not merely exaggerated but un- founded [..] Cirque du Soleil is not 100 big to fail, but the company is to inventive and successful to quickly start counting out, like so many clowns in a car. Background Note Cirque's journey began in the early 1980s in Baie-Saint- Paul. Canada. Les chassiers de Baie-Saint-Paul, a theater troupe ounded by Gilles Ste-Croix, entertained the people of the city by walking on stilis, juggling, dancing, breath- ing fire, and playing music Guy Lalibert Laliberte) who started out as a street performer in Quebec, was a part of the troupe. The troupe went on to found Le Club des Talons Hauts (the High Heels Club), and then, in 1982. organized La Fte Foraine de Baie-Saint-Paul, a cultural event in which street performers from all over performed and exchanged ideas. In 1984. Quebec City was celebrating the 50th anniversary of Canada's discovery by Jacques Cartier, and the Quebec gov- ernment needed a show that would cany the festivities out across the province. Lalibert presented a proposal for a show called Cirque du Soleil (Circus of the Sun), and succeeded in convincing the government to provide them with a grant of CS1.5 million. The show was a visual treat with incredible PC4-5 PC4-6 PART 4 COMPREHENSIVE CASES artistic skills. Thus Cirque was born with the assistance of the Quebec government. Lalibert chose the name Cirque du Soleil for his company as he saw the sun as a symbol of youth. energy, power, and light. The company's mission was to invoke the imagination, provoke the senses, and evoke the emotions of people around the world. * Cirque was not a tra ditional circus as no animals were used for the acts. Its shows were spectacular with live performances, opera, and theater, with lavish costumes, huge sels, original music, and special effects. In 1984. Cirque reported sales of US$1.7 million and it employed about 73 people." Cirque's first production, Le Grand Tour, debuted in the small Quebec town of Gasp, and was then performed in 10 other cities across Quebec. The positive response from the audience encouraged Lalibert to expand Cirque's operations outside Quebec. In 1985. the troupe performed outside Quebec for the first time when it held a show in Ontario. This was fol. lowed by shows in Ottawa, Toronto, and Niagara Falls. The fol lowing vear. Cirque organized shows across Canada and put up several performances at the Children's Film Festival in British Columbia and at a world fair in Vancouver. By this time. Cirque had a seating capacity of 1500. However, in late 1985. a result of a series of flop shows, Cirque went deep into debt, to the tune of US$750,000. But the company did not go bankrupt as Cirque's financial institution, the Desjardins Group. postponed the company's debi payment of US$200,000. The Quebec goverment also granted sufficient funds to the company so that it could sustain itself for another year. And in 1987, the status of Cirque was changed from non-profit to a for-profit entity. That year, the troupe was invited to the Los Angeles Arts Festival. Although the company was facing Financial problems, Lalibert decided to take a chance and his troupe staged the show "We Reinvent the Circus at the festival. The show was a huge success and marked Cirque's entry into the US. In 1990. Cirque debuted in Europe. staging shows in London and Paris. By 1990, Cirque's seating capacity was 2,500 and the tickets were sell ing for as high as US $33.5.10 In 1992. Cirque entered into a year-long agreement with Mirage. a Las Vegas hotel, te perform a show Nouvelle Experience following its huge success, it launched an- other production called "Mystere, which was also staged at Mirage. The following year. Cirque entered into a ten- year contract with Mirage for the production. Steve Wynn (Wynn), owner of Mirage. also built a permanent facility for Cirque at a cost of US$20 million at his new resort, Treasure Island, which opened in 1994. Cirque's sales increased from US$ 30 million in 1994 to US$110 million in 1996. This growth was attributed to the success of the show 'Mystere'. In 1997. Wynn constructed a US$60 million theater for Cirque at Bellagio. Las Vegas. Walt Disney also constructed a permanent theater to house Cirque at Walt Disney World in California. The same year, a US$22 million facility for rehearsals and costume designing activities called "Creation Studio' was created by Cirque in Montreal. This also served as the company's headquarters. All of Cirque's shows were created and produced here. In 2000, sales reached US$407 million. In January 2001 Lalibert appointed Daniel Lamarre (Lamarre), who till then lud been the CEO of the TVA Group," as president and chief operat ing officer of Cipe. In 2003. Cirque was rated Quebec's most admired company. A year later, Cirque computerized its recruit- ment processes by appointing staffing management pewider Tideo Corporation to deploy Web-based tools to allow candidates to apply for positions online. Instead of manually processing the nearly 50,000 applications received annually, Cinque could manage the recruitment process electronically from the first contact to the final appointment. In April 2004. Cirque Bud to pay US$600,000 to settle an HIV discrimination case against it. A performer with Cirque, Matthew Cusick, filed a discrimination complaint against the company in the federal court after he was asked to leave as he had tested HIV positive. The settlement mandated that the anti- discrimination policies of the company be revised and all the em ployees be provided anti-discrimination training. Following this incident, the HR department was given training on the prevailing discrimination laws and the responsibilities of the empleryers. All the employees spread across the world were evacated about HIV and other diseases by experts in the field. The case proved to be an eye opener for Cirque, which had always had the reputation of being an undiscriminating, gay friendly organization. As a result of the case. Cirque came up with new HR policies and practices. To manage a diverse workforce, Cirque formed a dynamic HR team to manage recruitment, training, and even planning out HR policies for its employees. In line with its global pres- ence. Cirque decided to decentralize its HR department. This was mainly because the performers of the touring shows were governed by the laws and policies of the countries in which they were performing at that particular point of time on issues such as taxing monetary benefits and allowances, maternity benefits. etc. In the absence of any company policy. Cirque's touring em ployees were covered by the laws of whichever country they happened to be working in at the time. For instance, a pregnant employee touring in China would only be eligible for the ma- ternity leave and benefits related to China. A full-time HR pro- fessional always accompanied each of Cirque's touring shows to help with specific issues like insurance coverage, immigra- tion, and work life balance. The touring shows also hired tem- porary employees for specific roles like ushers, cashiers, and sales people at the merchandise tents. Many of these employees followed the touring shows to various cities. If the temporary employees' performance was really good, they were absorbed into the company as permanent employees To manage all its personnel. Cinque had four separate head- quarters. Apart from the Interational Headquarters in Montreal there was the Headquarters Europe in Amsterdam. Headquarters Las Vegas in Las Vegas, and Headquarters Asia-Pacific in Singapore. Despite this decentralized approach to workforce management, Cirque ensured that the company functioned as a combined family. In 2006, Lamarre replaced Lalibert as Chief Executive Officer as the latter wanted to devole more time and energy to guiding the creative processes at Cirque. In 2007. Cirque initiated a major change in its criteria for evaluating employees with a view to promoting commitment and sustainability. Employees were assessed based on their CASE 9 CIRQUE DU SOLEIL'S GLOBAL HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PRACTICES PC4-7 contribution to Cirque as a creative business and responsible citizen, in addition to job performance. Employees were ex- synchronized swimmers, and cliff divers. The company also hired from circus schools. Sometimes it was difficult to approach pected to act as Cirque's ambassadors, showing respect for certain artists. For instance, dancers and actors had agency repre- people, cultural diversity, and the environment and integrating more responsible practices in their daily work, sentation while some sportspersons could not be approached until In 2008, Lalibert sold 20% of his stake in the company to they were done with their careers. Cirque also maintained a cer two Dubai firms for US$600 million, but later reclaimed half tain protocol while approaching artists from other circus families. "There's a certain ethic and a respect on our part - maybe we will the stake. In 2008. Cirque reported sales of US$733 million. The major portion of Cinque's revenues was generated from not approach the artist, maybe we will approach the grandfather or the father or the mother and tell them -ask them - Where is ticket sales. In addition, it earned a significant amount of rev- this artist in his or her career? Because some of these circus fami- enue from the merchandise it sold at the performances. Cirque lies, they depend on each other. (A) flyer needs a catcher,catcher had also expanded into media outlets such as music, books, needs a flyer," said Monson television, film, merchandising, and websites. In December The company had a website available in seven languages to 2012. Cirque entered into a joint venture with Bell Media to manage recruiting. On an average, Cirque received 30 to 40 ap- form Cirque du Soleil Mdia that developed media content for plications per day not just from artists, but from business school television, film, digital, and gaming platforms. Cirque's subsid- graduates seeking opportunities in IT, finance, accounting, and iaries included 45 DEGREES, Cirque du Soleil Hospitality, legal and human resources. Where the artists were concerned, Cirque du Soleil Theatrical, 4U2C.1and Outbox,'S As of they had to first submit a video to Cirque showcasing their tal- 2014. Cirque had 20 shows around the world across five con- ent. The company then invited exceptional candidates for au- tinents and employed about 4,000 employees globally, includ- ditions that were held globally throughout the year. Auditions ing 1,300 artists. People from more than 50 nationalities were could last a full day and artists were asked to perform outside of represented in the company and 25 different languages were their comfort zone. For instance, swimmers were asked to sing spoken among the employees and artists. The average age of a and acrobats to dance. This was done to assess the versatility of Cirque employee was 35 years. the artists. Discussing the company's recruitment strategy. Line Glasson (Giasson), director of international casting at Cirque, Selection and Training said. "We often choose for personality. One candidate may be lower on the technical side, but we know that person will bring As Cirque required people with a wide range of skills, it ap- something special to the stage. Soft skills are just as important pointed talent scouts and recruiters who travelled globally as technical skills: hunting for artists, creators, coaches, and musicians. Cirque Prospective candidates were evaluated based on five recruited talent from all over the world. To recruit artists, it de- attributes creativity, commitment, responsibility, team-play. pended on a casting team supported by a global network of part- and passion. Oenendly, the company preferred young people ners who discovered and recommended artists the world over. in their curly twenties as it felt that such people would bring To achieve both athletic and artistic perfection, these scouts with them different viewpoints and energies. The most impor- often looked for athletes who had competed in the Olympics tant critenon that Cirque looked for in an artist was passion. or other championships. They were regulars at Olympic and According to Guilbault. "If you want to be excellent if you World Championship competitions and worked closely with want to go further, hire people who have some kind of passion. Olympic coaches and teams to help athletes consider a career and just put a bit of magic in it. It works. A bit of craziness with Cirque after their competitive years were over. For resi. doesn't hurt.*19 dent shows, Cirque hired people from the local community. After joining the company, all new hires were required Talking about Cirque's recruiting strategy, Pat Norris (Norris), to go through a formal training period that generally lasted director of human resources at Cirque's Resident Shows from a few weeks to four months at the Creation Studio be- Division, said, Talent acquisition is critical in an organization fore being inducted in a show. Cirque adopted a competency- like ours. We rely on recruiting the best and most outrageous based training approach that was designed to allow leamers performers. They have to be able to bring the show to life night to demonstrate their abilities and enhance their competencies. after night. They do it with skill and spirit repeatedly, system- The training facility at Cirque's headquarters included three atically, and always keep it fresh. Every moment in a live show acrobatic training rooms, a dance studio, a studio-theater, and is a discovery of what can be done. That is our magic. When weight-training facilities. At Cirque, artists were trained on two levels. One was the acrobatic component that taught them all I provide great service in HR - and that's an innovation unto 16 itself here - it impacts the performers on stage." of the movements the act required, while the other was the ar While hiring people, Cirque relied on two platforms, one tistic element that focused on developing their facial emotions an art talent acquisition group, and the other a casting agency. in order to play a character. While training, artists were taught Cirque's casting director, Krista Monson (Monson), was respon- about the safety aspect as well. They were trained on how to handle the equipment, safety moves, and proper positioning on sible for casting artists. She worked with a team of 60, including the acrobatic equipment. To supervise training programs, the 21 talent scouts, who worked in several countries and across social Creation Studio employed close to 100 trainers from around the media platforms to find the best gymnasts, trapeze artists, contor- world who were experts in sports, acrobatics, dance, music, and tionists, jugglers, ballet dancers, clowns, mime artists, musicians, PC4-8 PART 4 COMPREHENSIVE CASES theater. Based on their area of expertise, ench trainer supervised the artists individually. Physiotherapists and fitness specialists were also available on site to look into the health and physical fitness of the artists. Cirque's stage director, Franco Dragone, described the whole training regime as being "like peeling an onion to get to the sweet, intense core." During the training session, artists stayed at the artists' residence, located close to the training facilities. The residence housed 113 rooms, each of which was equipped with air conditioning, a TV. Intemet ac- cess, a small refrigerator, a microwave, and a private bathroom. The residence also had other facilities such as a communal area, a gym, a kitchen, a lounge area, and even a games room. However, assimilating seasoned artists and athletes into Cirque's atmosphere and persuading them to take artistic risks was a daunting task, according to the company. Cirque was all about creativity, imagination, and risk taking - qualities not always associated with athletes. Moreover, a majority of the gymnasts, athletes, and dancers came from competitive back. grounds where individual excellence rather than team work was instilled. Integrating these artists with the company's culture could therefore be a difficult task, Cirque felt. Talking about the challenge. Monson said. "They're seasoned pros in what they do, and we want that high level. But we also want them to do dances in the background dressed in weird costumes. Even if you're talking about an Olympic diver, artistic excellence usually not something in their vocabulary -20 In order to help new recruits become absorbed into the Cirque workforce and overcome cultural shock and resistance, Guilbault and her team developed certain strategies. For instance, hiring managers were instructed to inform new employees that it might take six months to understand and acknowledge how the company functioned. All new hires were encouraged to try out different roles in as many operations as possible and gain a comprehensive view of how Cirque worked. They were given the opportunity to be cre- ative and develop their own routine. The whole system supported them in their endeavors. As part of a program for young mentees. new recruits could work alongside senior managers and contribute in creating new shows. Sometimes trainees were taken backstage to understand the way things worked. According to Lyn Heward (Heward), former Vice President, Creation and President and COO of the Creative Content Division at Cirque, "For us training is cre- ative transformation and recruiting is easure-hunting. Even at Cirque, we have to work hard at it. We too could lose our soul if we didn't have the commitment. We have a Creative Synergy department, whose preoccupation is in doing this. Creative Transformation is the most important doorway for us. We're trying to find the pearl,' the hidden talent in that individual. What is the unique thing that person brings? I think you need to dig deeper as we call it treasure-hunting. What makes that person tick and how does it contribute to the work that you're doing?21 the employees were the backbone of such a culture. The com- pany fostered an environment that encouraged productivity, creativity, and individual growth. At Cirque, artists from over 50 countries worked together to put up one of the big- gest theatrical extravaganzas in the world. Diversity being at the core of its business, it was imperative for Cirque to build a work environment where the focus was on the em- ployees' quality of life and health and well-being. Hence. Cirque created an open, safe, creative, and friendly work environment and provided opportunities for artists to grow both professionally and personally. "Cirque does not cut cor- ners. They put care first, and that had never been done by a circus before 22 said Mark Borkowski, founder and head of Borkowski.do.23 The atmosphere at Cirque was open and inviting and artists were given the space to freely share their ideas. Comparing the workplace at Cirque to a playground, Heward said, "At Cirque du Soleil, the ideal working environment is a fantastical play- ground" that has rules but that still allows artists, designers, and employees to see the world through the eyes of a child. Viewing the world with eagerness, curiosity, excitement, and playful- ness establishes an open, inviting atmosphere that encourages thought and action and takes into consideration that it is dif- ficult to be creative in isolation - 24 Cirque was aware that happy and satisfied employees were more productive and would positively contribute to the business. Hence, it treated its employees with professional. ism and respect. It tried to create a family atmosphere among its diverse workforce as it promoted teamwork and growth Employees enjoyed working in a comfortable environment that included flexible hours and modern and open work spaces. Unconventional clothing and appearance, such as tat- toos, piercings, and casual dress were acceptable at Cirque, even at its corporite headquarters. "It's not the way you dress that's important, it's what you do. If somebody has blue hair, that's fine; we won't put any judgments past them. Some companies could gain to be a bit looser, because at the end of the day it's the results that matter. It's not what someone looks like said Guilbault. Complimenting the hard work put in by the artists, Cirque offered them a host of facilities, particularly for its traveling staff. Services included physical therapy, chefs to prepare meals, cocktail hours, and barbeques and fun parties where employees could socialize and spend time with their families. The manage- ment too was very approachable. "I hope that they always like working at Cirque, that they have fun. Fun is an important part of the job here, because if we don't have any fun, how can we provide a fun show?" said Mare Gagnon, former vice president of corporate services, Cirque. At its international headquarters in Montreal, employees had access to a gourmet kitchen, an outdoor patio, free trade coffee offered free of charge, a gym, and a variety of fitness classes offered at a minimum fee. There were also acrobatic and artistic training rooms for the artists to train (refer to Exhibit I for general conditions at Cirque). The chefs served balanced and tasty meals offering a wide range of tastes. Food was offered at reasonable prices and employees could even take it home. Birthdays, personal achievements, and Culture at Cirque Cirque flourished on a culture of risk-taking and creativity that nurtured talent and gave people an opportunity to show- case their skills. The work culture at Cirque was based on involvement, communication, creativity, and diversity and CASE 9 CIRQUE DU SOLEIL'S GLOBAL HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PRACTICES PC4-9 EXHIBIT I General Conditions at Cirque du Soleil On Big Top touring shows: Artists are offered one or two-year contracts at a very competitive salary. Artists can usually expect to train an average of 12 hours a week. Lodging is provided in the form of a private room at a hotel. Market allowance is provided. . Big Top touring shows perform 300 to 350 times a year. Overview of general conditions on arena touring shows: Artists are offered one or two-year contracts at a very competitive salary. Artists can usually expect to train an average of 12 hours a week. Lodging is provided in the form of a private room at a hotel. Market allowance is provided. Arena touring shows perform 270 to 310 times a year. On resident shows: Artists are offered one or two-year contracts at a very competitive salary. Artists can usually expect to train an average of 12 hours a week. * Lodging is provided until two weeks after the artist's integration into the show. . During the creation period of a new show. lodging is provided throughout the process in Montreal and for four weeks when the production moves to its resident city. Resident shows perform 380 to 470 times a year. Source: Adapted from www.cirquedusoleil.com/en/jobs/casting/work/general-condition.aspx local and national holidays were celebrated whenever possible both on touring and resident shows. Relishing his experience of working for Cirque, an employee said, "Fun place to work, Hors du commun! Motivating work environment, a lot of ac- tivities all the year long. During the summer, terrace. BBQ. drinks, beach volley-ball, tons of activities, and entertainment. Danse, Yoga, Zumba, Choir, Sports, etc. Two nice cafeterias, very good variety of meals. Good benefits and fair pay, very good balance between life and work. 26 Cirque went to great lengths to provide an enjoyable work environment for its touring employees as touring shows were often beset with problems such as homesickness and lack of personal space. On such shows, employee welfare was a 24/7 responsibility for Cirque as it had to look into issues like housing, food, and language barriers. Sometimes artists were even allowed to bring their families along on tours. Social activities and exchanges were conducted to enable artists to meet up, get to know each other, and share their experiences. For instance, during the run of the show Totem at the Royal Albert Hall in London, which had 52 cast members. Cirque took good care of its performers. The show travelled with four chefs who prepared tasty meals using local ingredients. Food was presented with color-coded labels to indicate its nutri- tional value. On Sundays, all the cast members brought their families along for lunch. Each artist had his/her own cubby- hole, filled with family photographs. According to observers, the work place was like a home-away-from-home and em- ployees bonded like family members more than co-workers. Working here has been the best opportunity I've been given. Although no job is totally perfect, this one is close! The am- biance in the office is friendly and outgoing, they amuse the employees with entertaining activities for all tastes and ages almost every week. Working in this creative environment has been a great experience so far and I hope to enjoy it for years to come! 7 said an employee. At Cirque, artists could establish careers. create families. and gan stuibility - all based on their talent. a ranty m the cites industry Cirque offered its employees several developmental opportunides dar allowed them to learn and gross and prevented them from getting staignant by working in one position for teo long For instance, Cirque suma a program called "Tapis Vert'. as part of which young employees eould work alongside senior managers for a specified period and also set involved in the ci ation of new shows. At Cirque, artists were free to express their ideas and creativity. In order to boost employee engagement, Cirque started an initiative across the company called Eureka in 2001. The program allowed employees from any department to hamess ideas that they were passionate about. The idea was to do away with the silo' mentality and establish a 'no-kill zone for ideas so that every employee contributed in the creative pro- cess. Benoit Mathieu, vice president of costumes and creative spaces, Cirque, remarked. "It's to give space to an idea so it can't be killed by the immune system of a big company, which tends to be very strong. We want to give people a tool to be heard, even if they are not part of executive management. We can process those ideas so they can either live or die. And if they die, they should die for a good reason, with people getting feed- back instead of them just disappearing into the ether. -28 Benefits Galore Besides offering employees a dynamic work environment, Cirque also provided them with a wide range of benefits and services. Generally, artists were hired on contract for a period PC4-10 PART 4 COMPREHENSIVE CASES EXHIBIT II Global Remuneration On all shows: Seniority lump sum . Four complimentary tickets per year to any resident or touring Cirque du Soleil show Ten reduced-price tickets to Cirque du Soleil touring shows Discounts on Cirque du Soleil merchandise Access to last-minute complimentary tickets for some shows, in some territories On Big Top touring shows: Market allowance is provided An average of two weeks of vacation per year during down periods Return transportation home at least once a year during down periods Ten statutory holidays Lodging and transportation between cities Lodging is provided in the form of a private room at a hotel. Medical, dental, disability, and life insurance coverage Bank of sick days Kitchen with choice of meals five to six days a week depending on the show schedule On our arena touring shows: Market allowance is provided An average of two weeks of vacation per year during down periods Return transportation home at least once a year during down periods Ten statutory holidays Lodging and transportation between cities Lodging is provided in the form of a private room at a hotel. Medical, dental, disability, and life insurance coverage Bank of sick days Catering services five to six days a week On resident shows: Typically, three extended dark periods of nine days or more Medical, dental, disability, and life insurance coverage Bank of sick days Access to the hotel cafeteria if available Source: Adapted from www.cirquedusoleil.com/en/jobs/casting/work/global-renumeration.aspx of 1-2 years at a very competitive salary. Sometimes depend- ing on the job, they were paid per show or hourly. On an aver- age, a Cirque employee earned anywhere between US$30,000 and US$100.000 annually (refer to Exhibit II for global remuneration) Irrespective of whether they worked at its International Headquarters or at touring or resident shows, the artists and technicians working in different divisions were entitled to many benefit packages (refer to Exhibit III for health ben. efits, Exhibit IV for travel benefits). However, these packages differed according to location and employment status. They generally included competitive salaries, paid vacations, insur- ance plans performance bonuses, lodging and transportation, medical, dental, disability, and life insurance coverage, retire- ment plans, gourmet buffet-style meals, and discount tickets to Cirque shows. The employees also had access to gymna- sums and training facilities to keep themselves fit for their performances. It was reported that under the new parental in- surance plan passed by the Quebec government on January 1. 2006, the benefits derived by Cirque employees during mater nity leave coupled with government benefits amounted to about 90% of their regular salary. 30 Annually, Cirque organized trips at a discounted rate to allow employees to travel to Cirque shows in other countries. A certain number of complimentary tickets were also given to regular employees and they were allowed to enter company draws as well to win show tickets and trips. Employees also received discounts on Cirque merchandise. They were gifted corporate attire on Cirque anniversaries. Cirque also offered the services of a tutor to the children of touring employees and child performers. In 2006, Cirque formed a partnership with a childcare center in Montreal. Under this partnership, 60 day care centers were set up, of which 30 were reserved for the chil- dren of Cirque employees. CASE 9 CIRQUE DU SOLEIL'S GLOBAL HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PRACTICES PC4-11 EXHIBIT 1 Health Benefits In addition to a medical plan (including dental coverage), a Health Services team is present on each show to assist artists in the following areas: Individual and group strength and conditioning programs Rehabilitative and injury prevention therapy Wellness education Exercise therapies (Pilates, yoga, etc.) Medical evaluations Physical capacity evaluation and consultation Nutritional support Emergency medical planning and care On-site emergency care Access to professional medical support Workers' compensation coverage Non-occupational insurance coverage Medical, dental, disability, and life insurance coverage Source: Adapted from www.cirquedusoleil.com/en/jobs/casting/work/health-benefits.aspx. EXHIBIT IV Travel Benefits Big Top and arena touring shows Travel at the beginning and end of your employment contract Travel between the cities on the tour A return trip home once every 12 months Local transportation between the site and your accommodations, if the distance is greater than 1.5 kilometres Lodging is provided in the form of a private room at a hotel Artist visa and work permit initiated and paid for by Cirque du Soleil Resident shows Local transportation allowance during the first two weeks of integration if you don't own car Lodging provided until two weeks after artist's integration into the show During the creation period of a new show: lodging provided throughout the process in Montreal and for four weeks when the production moves to its resident city Artist visa and work permit initiated and paid for by Cirque du Soleil Source: Adapted from www.cinquedusoleil.com/en/jobs/easting/work/travel-benefits.aspx Communication Employees holding similar positions in different divisions At Cirque, communication was transparent and hierarchies were encouraged to form practice communities in which they were non-existent. Good communication was important to could share their work methods and approaches. Whenever em- ployees had a problem or an issue they could easily write or ensure that all employees had access to the same information talk to their supervisors about it and expect the issue to be ad- and to maintain cohesion among the divisions. Internal com- dressed. Regular meetings were held to help employees express munication tools including both electronic and print media their views and concerns. These meetings were called "Tapis were created, and each division was invited to contribute to Rouge for the artists and blue or green carpets for the other these tools. These communication tools ensured that every em- employee groups. The company also had an interactive intranet. ployee had a voice and was kept updated about the happenings which made communication simple among the employees at the company. For instance, in 2006, a hotline was set up to spread out across the world. Employee feedback was consid- Lamarre whereby employees could ask him questions through ered seriously whenever an important policy was introduced or e-mail and get replies via an electronie bulletin available to all revamped. The HR managers visited different Cirque venues employees. and discussed the issue with a few employees. According to PC4-12 PART 4 COMPREHENSIVE CASES Suzanne Gagnon (Gagnon), former vice president of human re- sources at Cirque, "We get better from this type of concerned employee than the ones who say. 'Everything's fine, thank you very much,' because then we're just getting what we want to hear. We want to hear what's wrong so we can fix it.31 Cirque ran three publications through which employees could communicate globally. 'Hand to Hand' was a fortnightly magazine which contained information about openings in the company, new tours, and the schedules of various Cirque shows around the world. It was more of a formal corporate periodical. The Ball', a monthly published at Montreal, mainly carried sto ries of Cirque employees around the world. It was like a graf- fiti wall where any employee could contribute his/her stories. For instance, there was a column called "Culture Shock' where employees would give their frank opinions about their experi- ences in foreign countries. It also contained the feature 'Be Your Own Bitch'. In another section, employees could write their complaints and suggestions and other insider jokes, uncensored by the managers and supervisors. The third one was 'Under the Bleachers', a publication from the company's Amsterdam office. The magazine featured funny photos, interviews and gossip. To ensure that employees in all the divisions become fa- miliar with its core business, Cirque provided them access to creative content. For instance, employees at its International Headquarters, whose work was less closely related to the pre- sentation of shows, were the first to watch acts by artists who had just completed their training. To keep employees updated about the new shows, lunchtime discussions with the creative teams were organized. project. In 2006, eight bursaries worth US$2,500 each were awarded to organizations where Cirque employees volunteered. To encourage employees to participate in cultural life outside their work, Cirque started the Support Program for Employees' Artistic Projects (PARADE) in 2006. The program helped employees in their artistic endeavours by providing them with advice and financial aid. The art work was then exhibited at Cirque offices in Las Vegas, Orlando, Los Angeles, and the International Headquarters at Montreal. According to industry observers, the PARADE program fostered cultural develop- ment among employees as well as encouraged participation in cultural activities. In 2007. as part of the PARADE program, more than US$10,000 was awarded to support employees' cre- ative projects in literature, cinema, circus, music, and the visual arts. Each year in 2012 and 2013, about 75 employees received support for their artistic creations. In 2011, to facilitate communication on sustainable devel- opment issues among its employees on touring shows, Cirque set up Global Citizenship Committees, which allowed employ- ees interested in environmental. community, and social justice issues to set up projects in their workplace. These projects in- cluded sustainable development awareness and education activ- ities for employees, implementation of a waste-sorting system at tour sites, and activities with local community groups. Social Involvement To promote the artistic pursuits of employees, Cirque started an innovation bursary called Talons Hauts Bursary' in 2005. The purpose of the bursary was to promote creativity among the employees and help them contribute to the organization's creative pool. Employees were encouraged to submit inno- vative ideas and projects related with the activities of Cirque such as shows, merchandising, hospitality, etc. In 2006, bur- saries totalling US$25,500 were distributed to six employees whose creation, marketing, and management projects were se- lected. Nearly US$30,000 in Talons Hauts bursary prizes were awarded to 14 employees in 2007. As part of its Cultural Action programs, Cirque offered artists the opportunity to exhibit their work at its International Headquarters and at its Resident Show Division offices in Las Vegas. The artwork was then displayed in employees' work settings to create a vibrant, stimulating environment. Cirque purchased tickets for performing and visual arts events, exhibi- tions, and shows and distributed them among its employees. Cirque's ticket purchase program allowed employees to attend artistic events free of charge. For instance, in 2006, Over 2.000 tickets, for a total of 90 productions, were distributed to Cirque employees in Montreal. In 2001, through the Cirquesters Do Their Part' program. Cirque recognized the commitment of em- ployees who became involved as volunteers in the community and offered them grants after assessing their role in a particular Health and Safety Since its inception, the safety and well-being of the artists on all its shows and training sites had been a prime concern for Cirque. For a venture as risky as a circus, providing a safe workplace for its employees who put in a lot of effort to pro duce spectacular shows was important, felt Cirque. Moreover, a number of risk factors were involved such as the difficulty level of certain artists' performances, high stress, and tasks involving heights, chemicals, and heavy equipment. Whether in the form of injury prevention, on-site emergency care, or nutritional support, Cirque maintained that ensuring the well- being of its employees was always a priority. At the company's International Headquarters and Touring Shows Division, em- ployees received training connected with the risks associated with their work from the moment a professional artist was hired and up to his/her indection in a show, he/she had to un dergo a comprehensive training program provided by expert trainers. Cirque also ensured that its equipment and work envi- ronments complied with the highest safety standards. The com- pany also came out with manuals on health and safety rules in the workplace. As a precautionary measure, Cirque appointed a health and safety team to inspect event sites and watch performers. This team suggested changes in case something was wrong. Cirque also followed the government-mandated workplace safety regulations in countries where its shows were held. "In some countries there's no legislation that says you need to provide workers' comp, or sometimes there's legislation but we're not there long enough to benefit from it. But we still want to offer coverage. So if there's a hole, we have Cigna cover it," said Hlne Thibault, a senior benefits manager at Cirque. CASE 9 CIRQUE DU SOLEIL'S GLOBAL HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PRACTICES PC4-13 Though Cirque had an excellent reputation for safety, it had witnessed some accidents over the years. In 2013, it was accused of six safety violations in connection with the death of a 31-year-old artist Sarah Guillot-Guyard" (Sarah) during a performance of the show "Ka" at MGM Resorts International in Las Vegas. Cirque was cited for not providing adequate training for the employee and for not properly assessing the workplace for hazards that required protective equipment in the theater. OSHA also said that Cirque had removed equipment from the fatality site before it ordered the company to do so. Cirque was fined more than US$25,000 in penalties. Talking about the ac- cident, Cirque spokeswoman Renee-Claude Menard (Menard) said, "Cirque du Soleil completed an exhaustive review of its safety policies and procedures in the wake of the tragic acci- dent involving Sarah. We have redoubled our efforts to ensure the overall diligence and safety of our performers and crew. We have received and reviewed the OSHA citations. Safety always has been the top priority for Cirque du Soleil, its performers, and crew members. 35 Earlier in 2009 a Ukrainian acrobat, Oleksandr Zhurov, died during training at its Headquarters in Montreal. Cirque took the initiative to support the family of Sarah and pay for her children's education. According to Kelia Scott, marketing manager, Acrometis, LLC.36 "It seems like Cirque du Soleil takes the safety of their performers seriously, especially since they have gone almost 30 years without a death during performances. Considering some of the stunts the artists pull off night after night, I do not think this case was the result of "cutting corners" or trying to skimp on safety measures. 1 think it was truly a tragedy and I appreciate that the company is doing their best to make sure the victim's family is taken care of and extending their efforts on safety procedures.?**? To prevent further accidents, Cirque set up Management Reviews and Health and Safety Committees to assess the risks involved in the performances in terms of health and safety. For instance, in 2014, a Risk Management Governance Committee was set up specifically to evaluate the risks associated with acrobatic performance and equipment. To nurture a healthy work environment Cirque implemented a health and well-being program at its Headquarters that focused on the lifestyle and the physical and mental health of its employees. As part of the first phase of the program, a walk-in clinic was set up at its Headquarters. Half a day per week, employees could consult a doctor available at the clinic for any problem. In order to main- tain a safe environment, Cirque planned to get seasoned profes- sionals to impart the necessary knowledge and training to its employees. singled out as being different or exploited based on their na- tionality or ethnic identity, said observers. Analysts, however, felt that the vast cultural gaps made communication difficult between artists and technicians and sometimes affected the quality of the show. In an effort to overcome this problem, Cirque's HR team conducted a basic language training program for the performers to facilitate open and unhindered communication. Whenever employees had a problem or an issue they could easily write or talk to their su- pervisors about it and expect the issue to be addressed. There were also many conflicts that arose due to cultural diversity For example, the laws regarding sexual harassment were more stringent in the US than in other countries. Kissing to greet friends and co-workers was quite regular in Canada but could be considered a form of sexual harassment in the US and some Asian cultures. In such cases, any complaint from an employee would lead to the company facing legal issues. Thus, it was important that the people at Cirque were made tolerant toward various cultures and traditions that were followed by different employees at the company. The employees were therefore edu- cated about the fundamentals of dealing with cultural diversity so that they could understand each other better. The touring troupes also faced the challenge of cultural adaptation. For example, in Japan, the performers had a tough time getting used to the stoic and formal behaviour of the audi- ence. The spectators provided little feedback to the artists, who were used to a more enthusiastic response. As a result, the HR department at Cirque received many complaints and resigna- tions from the artists. As a solution to this problem. Cirque partnered with FGIWorld (FGI). a Toronto-based work force counselling company. Fl imparted cross-cultural training for the next group which was to four Japan. They developed "An Introduction to Life in Japan, 1 a highly interactive training pro- gram designed to make the performers aware of the local cus- toms, differences in communication style, Japanese greetings. and even navigation on the public train system. The program was quite successful and many artists expressed an interest in returning to Japan for more tours. Similar training programs were planned for troupes touring across Europe too. Cirque also offered an Employee Assistance Program (EAP) for its touring professionals. This program was designed to provide professional help and counselling for international artists who suffered from high levels of mental stress and frustration. It also included helping the performers overcome the challenges of cultural differences. Despite the cultural diversity, Cirque ensured that it functioned as a unified whole, bonded by a common set of workforce principles and practices. It tried to maintain cohe- sion among its employees by organizing social activities and conducting exchanges whenever possible between the shows. Through such events, employees were able to meet and get to know each other and to share their experiences. Exchanges were sometimes paid for entirely by the tour. But in most cases, each employee contributed a small part of the costs. Commenting about the cultural mix at Cirque, an employee said, "The most difficult aspect of the job other than the physical intensity was making sure every team mate was satisfied, which was difficult. Bridging Cultures As of 2014. Cirque's employees and artists represented more than 50 nationalities and spoke 25 different languages. Cirque valued the diversity of its employees and respected their indi- viduality and viewpoints. Solo acts were never distinguished by introduction, technique, physique, or language. Cirque was an equal opportunity employers with the goal of maintaining a workplace free from any form of diserimination. Though its shows were diffusions of various cultures, artists were not PC4-14 PART 4 COMPREHENSIVE CASES My team consisted of 3 Russians, a Brazilian, 3 Ukrainians, 2 American, 1 Frenchman, and I Chinese guy. Obviously the lan- guage and cultural differences proved challenging. However it always worked out. Coworkers were some of the most interest ing people in the world and the entire company was managed very well. in Montreal. Through this program, Cirque helped many of its performers successfully discover and pursue new interests in a variety of fields. According to the company. "We not only value our artists for what they can bring to the stage but also for what they can eventually contribute when their performing days are over. We have had several artists make the transition from performance to coaching or stage management, while oth- ers have successfully moved on to join our Casting, Scouting. and administrative teams in Montreal. For those artists who are more attracted to the technical aspects of the theater, our shows provide a very cutting-edge place to work and learn. Having knowledge of the most modern theatrical technologies, and ac- cess to people who can show you how to master them, opens doors to invaluable skills you can take with you anywhere. 4 Career Transition Cirque knew that the career of an artist was short-lived and at one point of time they would have to step out of the spot- light. To help these artists pursue their dreams and look for an alternative career after their performing years were over, Cirque launched a career transition program. "Crossroads. in 2003. The program offered a variety of choices to the artists to continue being a part of the Cirque family. For example, un artist who was looking for an alternative career and had in terest in stage management could meet one of the employees from the stage management division of the company through the transition program. The artist was provided guidance and assistance regarding the steps he/she would have to take to achieve a career shift from being a performance artist to an em- ployee providing stage management support. "Some perform- ers struggle to adjust to life after Cirque. It's not just laundry, meals, medical care, education (there is a school on site) that are provided, the experience is holistic. If you get injured, the company will make sure you can get another job, train in other areas, or study for an MBA. Another precaution for life on the outside: every Cirque artist must learn to do their own make- up to the highest standard: not to save money, but to ensure they have another skill to take away with them," noted Lucy Jones, former Strategic Events Editor at the Telegraph.2 Some of the other alternative employment opportunities provided were those of fitness coach and naturopaths. And the company also videotaped veteran artists as they shared their thoughts on what career moves had or had not proved success- ful for them over the years. These videos were then shared with artists who were in a career transition mode. This went a long way in helping them to choose their future career paths. These artists were also provided with a guide. "My Career Reflection Guide', that had six modules filled with advice and suggestions for the artists to transit smoothly into the next phase in their ca- reer. "Because our artists are so passionate and so intense, you have to work things a little differently. You can't just hope to put together a traditional career planning program and have them go with the flow.43 said Gagnon. In addition, at Cirque a career development advisor was always available to the artists. The advisor provided the artists with the required support to come up with a career plan con sidering various aspects like aspirations, needs, skills, etc. If the artists wanted to study further or complete the education that they had left midway, the advisor helped them in finding the right programs and the details of institutions offering those programs. He/she also guided them on career options that they could consider both within and outside Cirque. More often than not, these artists were absorbed by Cirque into its coaching, stage management, casting, scouting, and administrative teams Challenges Aecording to industry experts, one of the biggest challenges for Cirque was to recruit and retain artists who were talented and rare to find. As Cirque shows had a lifespan of about fif- teen years, it was important for the company to not only find the best performers but also retain them for a long run. Moreover, as Cirque's success depended on the creativity and excellence of its employees, managing and retaining them was vital, they felt. In 2011, the company's annual attrition rate was 20%,45 Though the artists were paid competitive salaries, it was difficult to hold them back. According to analysts, one of the main reasons for the high attrition rate at Cirque was the difficult working conditions, particularly for the touring artists, who had to go through many relocations and a large number of shows ench weck Admittedly, the circus is a booming cultural industry. But the working conditions are far from ideal, at least according to murmurs in the industry. 16 remarked Michel Beauchemin, head of the APASQ. According to observers. artists at Cirque worked in the most gruelling situations and their spectacular performances on stage resulted from hours of planning, practice, and attention to details. It was observed that artists had to perform up to 3 times a day and 5-6 days a week. They were expected to rehearse for an average of 12 hours a week. According to Guilbault, "Cirque is a great company, but s also a very demanding company. There's a perception that we're always having fun, fun, fun, but the reality is we also work very hard. 18 Another problem for Cirque, according to analysts, was scouting potential talent, investing loads of money and time in training them, and then having to replace them owing to some problem that might arise. It became all the more difficult if an artist was unique and either difficult or impossible to replace. they said. "As soon as we find somebody really unique, we are proud and very excited for a possible new creation. But we are playing against ourselves, because there's only one." said Giasson. A case in point was a 25-year-old acrobat Alan J. Silva (Silva), from Brazil, who was just 3 feet 10 inches tall. A role was specially created for Silva in a show called "Zumanity" where he appeared throughout the show, dancing and flying through the air with a 6-foot-tall female gymnast. However, one day Silva hurt his shoulder and had to undergo surgery. CASE 9 CIRQUE DU SOLEIL'S GLOBAL HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PRACTICES PC4-15 Though another person with the same appearance was brought in to play his part, it did not work and the act was made into a solo until Silva returned. Cultural diversity was also an issue. Managing people of different nationalities who spoke different languages was a challenge as it complicated communications. People of the same nationality often stuck together and did not mix with oth- ers. Moreover, the company had to deal with stereotypes and preconceptions. Cirque was also criticized for becoming too structured and not allowing individual performers to excel and providing very few career advancement opportunities, "People are often promoted from being an artist up through ranks of management and have very little competencies as managers. Poor decisions, conflicting messages to employees, not much innovation regarding the workplace, few opportunities to ad. vance your career." pointed out an employee who had worked at Cirque for more than five years. there's also one of the factors that we let grow with our growth and that was our expenses. 12 Meanwhile, Cirque's shows were also being criticized for being too similar and lacking originality. Analysts felt that there was some dilution in the quality of their shows. According to David Rosenwasser, a former circus executive, "I'm not as awed as I used to be. The shows are almost indis- tinguishable to me. In 2013, revenues dropped to US$850 million from US$1 billion in 2012 though the company re- ported profits. The fall was attributed to a drop in the num- ber of shows. poor ticket sales, tough economic conditions, and growing competition. According to Lamarre, the troubles "certainly brought a lot of humility to the organization: 35 Going forward, Lalibert planned to sell about 20% to 30% of the company to outside investors and revise Cirque's structure and growth plan. He also planned to expand Cirque into new markets such as China and India and refocus its business from circus shows to other ventures. "Cirque is a hive. There is activity everywhere. It's all exciting, and it's all about the show. When I was first hired we were a very dif- ferent organization. It has been a thrilling ride to get to where we are today, and we are by no means finished. The future is extraordinarily exciting. It is a privilege to serve such an exceptional company, 1156 said Norris. Lost Its Way? In 2012, for the first time in its history, despite generating more than CSIbn (634m) in revenues from its shows glob- ally Cirque did not turn a profit. By August 2012, Lalibert decided to lay off some of its employees and cut the number of new touring shows. In 2013, Cirque laid off 400 people, mostly from its Montreal headquarters, citing production costs and ex- penses. The layoffs represented 8% of the company's global workforce. The company decided to cut down the number of shows in 2013 to 400 shows compared to 600 shows in 2012 as each show cost as much as US$25 million to develop. Also Cirque started making other cuts including giving out fewer anniversary jackets for employees to cutting out child perform- ers and tutors. Reportedly, the cuts amounted to US$100 mil- lion of savings. Dismissing rumours that Cirque was failing, Menard said, The first thing to say is that the Circus is not in crisis. Let's get that straight. We had a record year in terms of tickets sold. We sold more than 14 million tickets this year. We had a record year for total revenue, with more than $1 billion. We're still pulling our rabbit out of the hat. This being said, Case Questions 1. Discuss the global human resource management practices of Cirque. Discuss the challenges faced by Cirque in man- aging its global employee base. Critically analyze the culture at Cirque. How, according to you, has the culture fostered creativity and teamwork in the company? 3. People from five continents and more than 50 nationalities are represented within Cirque. How does the company manage such culturally diverse talent to gain competitive advantage? 4. What steps should Cirque take to retain its employees and preserve its culture