Question: Please answer the following questions and make it about one page long: What is the basic theme of the article? Try to state it in

Please answer the following questions and make it about one page long:

- What is the basic theme of the article? Try to state it in just one paragraph.

- Did the article present a good support base? Theoretical framework? Explain.

- What additional questions are suggested by the articles conclusions?

Thank you.

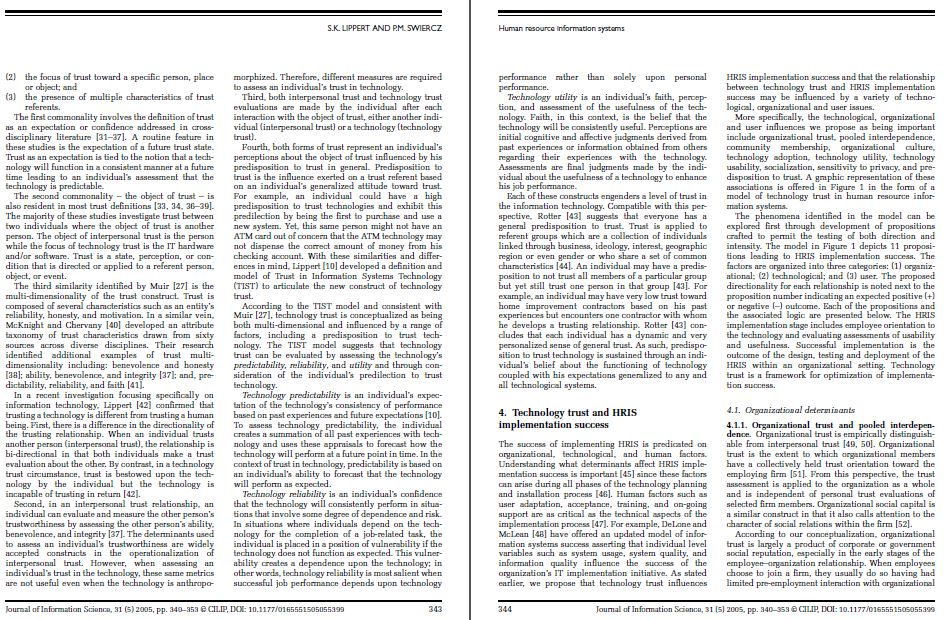

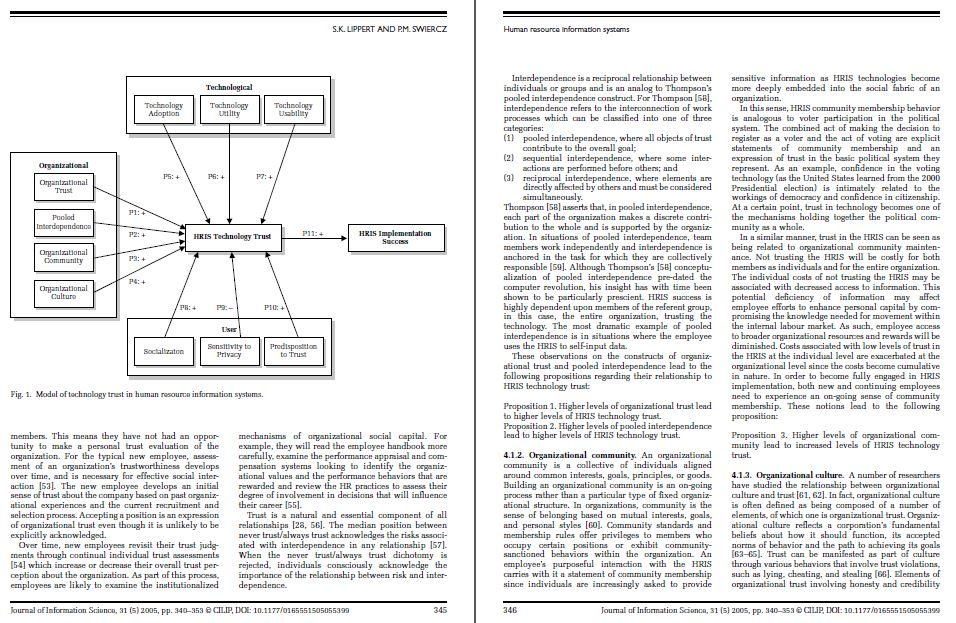

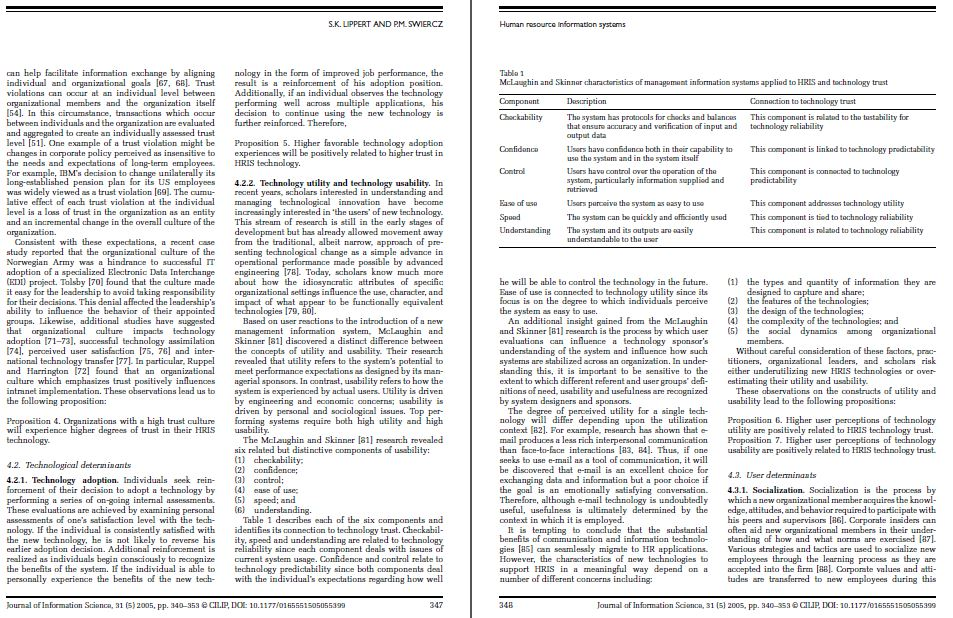

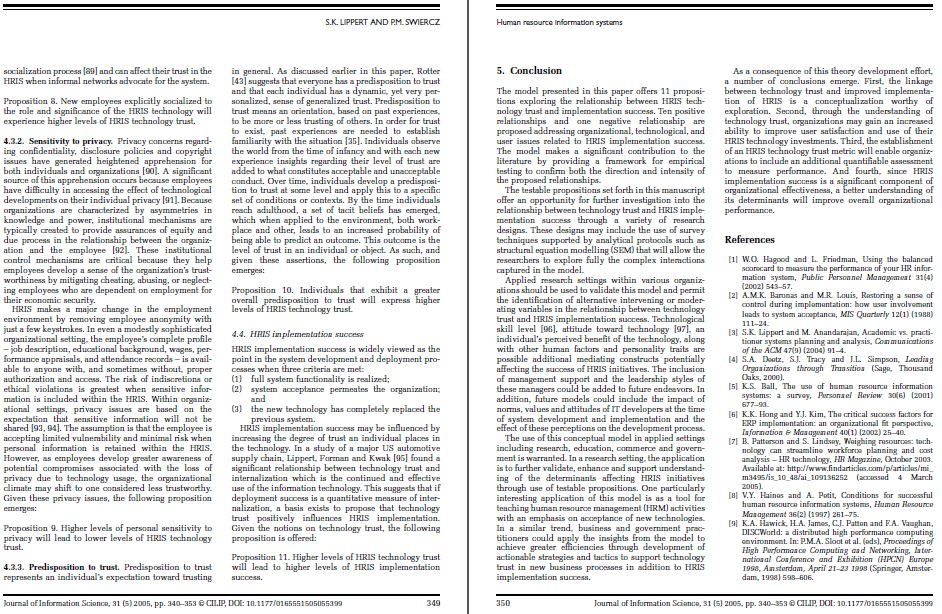

JIS Human resource information systems (HRIS) and technology trust Susan K. Lippert Department of Mosogonent, Lellow College of Business, Drexel Vaiversity, Philadelphia, USA Paul Michael Swiercz Department of Mosogonent Science, School of Business and Public Management. The George Washington Diversity, Washington DC, USA trust influence an individual level of trust in the TIRIS technology technology trust) and ultimately the wc of an HRIS Implementation price. A summary of the relationship between the key contracts in the model and recommendations for future research are provided Keywords: technology trust: human resource infor mation systems systems implementation; organi ational trust; pooled interdependence; ornnimational community; animational culture technology adaption technology utility technology usability: socialization; sensitivity to privacy: predisposition to trust Roxcavod 25 January 2005 Ruvised 10 March 2005 1. Introduction Abstract Scholars in many disciplines have considered the antecedents and on e of various forms of trust. This paper general 11 pmpositions exploring the relationship between Human Resource Information Systems (HRIS) and the trust an individual place in the animate technolon technology trust and models the effect of those relation- ships on HRIS Implementation Specifically rantatal, technological, and wer factors are con- sidered and modeled to rate a set of estable propesi- Bons that can subsequently be investigated in various rantaalweg. El propositions are offered su- proting that organizational trust pooled interdependence, rantatal c o ntrational culture, tech- molog adoptie, technology to technolo ability socialization, selvity to pracy, and predisposition to Hutan Resource Information Systems) CHRIS) imple mentation such as emr a significant chal lenge for organizations attempting to justify planned investments or recover expenses ociated with investments already incurred 1. In the information technology (IT) literature, a number of ons have been offered to explain implementation files Nonetheless, new determinants of implementation SUCCESS are required because the Editional explana tons - limited user intention 2. poor planning al. misation of technology to existing organisational business processes 14 and limited research -are inadequate in the face of the unique challenges associated with successful TRIS implementation SIA concurrent organizational challenge is the creation of performance metrics to the value-added contri bution of new HRIS initiatives 11.6L Suresful implementation of new and upgraded human resource information systems requires a more encompassing Correspondence de Susan K Lippert, Ph.D., Drul Uni- ursity. Lalow College of Business, Department of Manage munt 101 N. Srl, Room21, Philadelphia, PA 19104 Email: lippu l adu 340 Journal of Information Science, 31 (5) 2005. Pp. 340-353 CUP, DOI: 10.1177/01 SOSO5399 S.K. LIPPERT AND P.M. SWIERCZ Human resource information systems to understand how technology trust impacts employee engagement with the HRIS. The purpose of this paper is to generate a set of 11 propositions exploring the relationship between HRIS and technology trust and to posit the effect of these proposed relationships on HRIS implementation success. Specifically, organizational technological, and user factors are considered and mnadeled to generate 11 testable propositions that permit the empirical investigation in a range of organizational settings. The paper is organized into five section, Section 1 intraducns the topic and explains how the presentation is structured. Section 2 provides the theoretical grounding for linking HRIS implementation with tech- nology trast. The third section explores trust and its relationship to technology, In Section 4, 11 propositions are offered to illustrate the relationship between tech- nology trust and HRIS implementation success. The paper concludes with a summary of the relationship between the key variables of the model and recomenen- dations for future research. perspective because technologies allowing for sophisti- cated human capital management are essential for competitive success in the contemporary world economy [7]. A successful model of HRIS implementa- tion succes must consider an expanded range of factors likely to influence acceptance of deployed technologies (8). What is required is a perspective that is more conscious af and responsive to the social and operational demands of distributed IT at the micro level [9]. In response to this need, in this paper we dengnistute that the construct technology that offers considerable promise toward the effort to explain why HRIS implementation is too often less than fully Sacessful. Technology trust can be defined as an individual's willingness to be vulnerable to a technology based on person-specific expectations of the technology's pre- dictability, reliability, and utility as moderated by the individual's predisposition to trust the technology 110, 11]. As showcased in the propositions offered below, we believe that a more focused understanding af how technology trust relates to HRIS deployment offers the opportunity to develop a broader range of strategies to improve implementation initiatives. A contemporary HRIS is a dynamic database of demographic and performance information about each ernployee. It comprises software, hardware, and systematic procedures used to acquire, store, manipu- late, analyze, retrieve, and distribute pertinent infor mation about an organization's human resources 12 13). Data maintained in an HRIS can be used as a con- petitive information resource for virtually all core man- agement functions including planning. Organizing monitoring, controlling and leading 1141, HRIS tech- nology supports strategic planning through the genera tion of labour force supply and demand needs. requirements and forecast lis). An HRIS maintains information on recruitment, applicant qualifications job specifications, hiring procedures, organizational structures, professional development, training casts, performance evaluations, workforce diversity, and employee attrition (15). With well-functionins HRIS. employers can quickly respond to a changing con petitive landscape by developing targeted conpense- tion and recognition programa, making accurate salary forecasts, tailoring benefit programs, determining where to invest scarce training dollars and, arguably most importantly, redeploying key personnel as market conditions demand 116. Because organizational success in a knowledge economy is disproportionately dependent on employee performance (17], it is becoming increasingly important 2. Rationale for the model but also serves individual employees by enabling them to become self-sufficient and in greater control of their personal data. On the positive side, if the employee is able to see a benefit in using the system, he is more likely to be motivated to input timelyaccurate and comprehensive data (24). By providing employees with access to their personal employment record. self- administered HRIS can provide the immediate feedback and validation essential to effective motiva- tional program design. An HRIS with problems can have the opposite effect. Employee concerns about the security of their personal information remain an important expany and public policy issue. In a case in early 2005, ChoicePoint, an information data storage company discovered that the expected security of their HR infomation was widely companised, leading to personal and proprietary data being opened to the public domain [25]. An outcome of this recent case is the requirement to conduct a com- prehensive investigation to determine how the data were disclosed. When something like this happens technology that is negatively affected by the exposed vulnerability of systems that had been promoted as reliable and secure. The effect is a compromise of an individual's technology trust, an outcome with the potential to negatively impact eenplayee willingness to enter accurate and timely personal data in the future. Second, the inclusion of HR functionality within full-service software technologies places additional burdens on HR and IT personnel. In particular, the introduction of Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems has challenged HR and IT personnel to learn and integrate the wide range of functions embedded within these systems. ERP systems developed by SAP. PeopleSoft, Oracle, Bann, and Lawson conbine depart- ment operations, including the HR function, into an integrated software program running of a single database oftentimes stored on a secured web server. These web-based systems enable departments to share information in ways not anticipated three decades ago when early HRIS software first began to emerge. With un ERP market expected to expand from $19.8 billion in 2001 to $31.4 billion in 2006 1211. the number of parties - suppliers, vendars, customers and a wide array of secondary stakeholders- with a vested interest in HRIS performance success continues to grow. Third is the emergence of self-administered' or 'self- service' HR management as a trend with wide-ranging trust implications Research by the consulting fir Towers Perrin (22 reported that the number of com- panies using HR self-service applications tripled between 1999 and 2000. In addition, HR departments using the internet as the medium for a self-service HR function experienced a 38% gain in accumcy, a 50% reduction in HR staff worklands, and a 100% improve ment in timeliness 22). Employens using self-service functionality can easily update and verify personal information, consult online lists of intemal job vacancies, access corporate hand- books, and receive notices about upcoming training sessions (23). Managers can analyze job candidate profiles online, construct salary models, view benefits programs, monitor abannten trends and retrieve government labour regulations and forts for compli- ance purposes. In addition, individual eenplayee per formance, evaluation, and career development can all be accomplished through an HRIS. One by-product of this technological interface is that these systems empower employees in non-traditional ways. Employees now have continual access to their personal information as well as the responsibility of ensuring that data in the HRIS is accurate and complete. Organizational members at all levels can quickly and efficiently access data while managers and supervisors can use the information for decision- making Systems empower employees by enabling them to have 24/7 access to their critical personal infor- mation via a web-based HRIS [24]. An enterprise-wide HRIS not only makes the HR function more effective Three important trends are linked to the investigation of the relationship between technology trust and HRIS implementation sucx . Finit, the number of firms investing in HRIS has dramatically increased in recent years 5. Over the last two decades, organizations have grown increasingly dependent upon human resource (HR) systems to increase the effectiveness of human assets and provide management guidance. Addition- ally, HR-specific competitive pressures and regulatory requirements are no longer restricted to large organiz- ations but are now of concern to large, mid-level and small companies 18. New technologies and reduced casts have enabled companies, regardless of fire size, to purchase HR technologies S, 19. As a consequence, human resource information systems have evolved into sophisticated IT solutions designed to manage a wide variety of human resource data and to provide analyti- cal tools to assist management in HR decision-making 118). The financial risks associated with IT use by both large and small enterprises are of greater relevance not only due to direct technology acquisition costs but also due to the high implementation expenses associated with time away from productive work in the form of downtime or training (20). As such, understanding the factors that impact successful implementation has economic implications for all employers regardless of Organizational size. 3. Technology trust - expanding the notion of trust Understanding the role of technology trust in the HRIS implementation success formula offers significant promise for explaining a major component of the implementation process. The notion of trusting an inanimate object is not new. Writing from the perspec- tive of a communications theorist, Giffin (26) suggested the entity upon which the trust is bestowed can be a person, place, event, or object. Thus, in this paper, the 'object of trust is the HRIS. Muir 1271 pioneered the use of a behavioral perspec- tive by building upon the interpersonal trust viewpoint developed by Reenpel, Holmes, and mainta 1231. In series of publications, Muir and her colleagues (27.29 30] employed an interpersonal approach to better understand the nature of trust between humans and machines and to determine the factors affecting this one-sided trust relationship. As a consequence of this effort, she identified three common trust elements: (1) the description of trust as an expectation or confidence; Journal of Information Science, 31 (5) 2005, pp. 340-353 CHIP, DCX: 10.1177/0165551505055399 Journal of Information Science, 31 (5) 2005, pp. 340-353 CLIP, DOI: 10.1177/0165551505055399 S.K. LIPPERT AND P.M. SWIERCZ Human resource Information systems morphixed. Therefore, different measures are required to assess an individual's trust in technology. Third, both interpersonal trust and technology trust evaluations are made by the individual after each interaction with the object of trust, either another indi- vidual interpersonal trust) or a technology (technology trust). Fourth, both forms of trust represent an individual's perceptions about the object of trust influenced by his predisposition to trust in general. Predisposition to trust is the influence exerted on a trust referent based on an individual's generalized attitude toward trust. F or exuenple, an individual could have a high predisposition to trust technologies and exhibit this predilection by being the first to purchase and use a new system. Yet, this same person might not have an ATM card out of concern that the ATM technology may not dispense the corect amount of money from his checking account, with the similarities and differ- ences in mind, Lippert 110] developed a definition and model of Trust in Information Systems Technology (TIST) to articulate the new construct of technology (2) the focus of trust toward a specific person, place or object; and (a) the presence of multiple characteristics of trust referents. The first commannlity involves the definition of trust as an expectation or confidence addressed in croS disciplinary literature (31-37). A routine feature in these studies is the expectation of a future trust state. Trust as an expectation is tied to the notion that a tech- nolagv will function in a consistent manner at a future time leading to an individual's assessment that the technology is predictable. The second comenonality - the object of trust -is also resident in most trust definitions 33, 34, 36-39). The majority of these studies investigate trust between two individuals where the object of trust is another person. The object of interpersonal trast is the person while the focus of technology trust is the IT hardware and/or software. Trust is a state, perception, or con- dition that is directed or applied to a referent person object, or event. The third similarity identified by Muir 1271 is the multi-dimensionality of the trust construct. Trust is Composed of several chancteristies such as an entity's reliability, honesty, and motivation. In a similar vein. McKnight and Chervany (40) developed an attribute taxonomy of trust characteristics drawn from sixty sources across diverse disciplines. Their research identified additional examples of trust multi- dimensionality including: benevolence and honesty 138); ability, benevolence, and integrity (37l; and, pre- dictability, reliability, and faith (41). In a recent investigation focusing specifically on information technology, Lippert [42] confirmed that trusting a technology is different from trusting a human being. First, there is a difference in the directionality of the trusting relationship. When an individual trusts another person interpersonal trust), the relationship is bi-directional in that both individuals make a trust evaluation about the ather. By contrast, in a technology trust circumstance, trust is bestowed upon the tech- nalogy by the individual but the technology is incapable of trusting in retum 42). Second, in an interpersonal trust relationship, an individual can evaluate and measure the other person's trustworthiness by assessing the other person's ability. benevolence, and integrity [37]. The determinants used to assess an individual's trustworthiness are widely accepted contracts in the operationalization of interpersonal inast. However, when assessing an individual's trust in the technology, these same metrics are not useful even when the technology is anthropo- performance rather than solely upon personal pert::. Technology utility is an individual's faith, percep- tion, and assessment of the usefulness of the tech- nology. Faith, in this context is the belief that the technology will be consistently useful. Perceptions are initial cognitive and affective judgments derived from past experiences or information obtained from others regarding their experiences with the technology Assessments are final judgments made by the indi- vidual about the usefulness of a technology to enhance his job performance. Each of these constructs engenders a level ofinst in the information technology. Conpatible with this per spective, Rotter (43) suggests that everyone has a general predisposition to trust. Trust is applied to referent groups which are a collection of individuals linked through business, ideology, interest, geographic region or even gender or who share a set of canno characteristics 44). An individual may have a predis- position to not trust all members of a particular group but yet still trust ane person in that group 43) Far example, an individual may have very low inust toward home improvement contractors based on his past experiences tout encounters one contractor with whom he develops a trusting relationship. Rotter (43) con- cludes that each individual has a dynamic and very personalized sense of general trust. As such, predispor sition to trust technology is sustained through an indi- vidual's belief about the functioning of technology coupled with his expectations generalized to any and all technological systems. HRIS implementation success and that the relationship between technology trust and HRIS implementation Success may be influenced by a variety of techno- logical, arganizational and user issues. More specifically, the technological, organizational and user influences we propose as being important include organizational trust, pooled interdependence, community membership. organizational culture, technology adoption, technology utility, technology usability, cinlization, sensitivity to privacy and pre- disposition to trust. A graphic representation of these associations is offered in Figure 1 in the fom af a nadel of Enchnology trust in human resource infor mation systeens. The phenomena identified in the model can be explored first through development of propositions Crafted to permit the testing of both direction and intensity. The model in Figure 1 depicts 11 proposi- t ions leading to HRIS implementation success. The factors are organized into three categories: (1) beganiz- a tional; (2) technological; and (2) user. The proposed directionality for each relationship is noted next to the proposition number indicating an expected positive (+1 or negative (-) outcome. Each of the propositions and the associated logic are presented below. The HRIS implementation stage includes einployee orientation to the technology and evaluating assessments of usability and usefulness. Successful implementation is the outcome of the design, testing and deployment of the HRIS within an organizational setting. Technology trust is a framework for optimization of implementa- tiones. 4. Technology trust and HRIS implementation success According to the TIST model and consistent with Muir [27], technology that is conceptualized as being both multi-dimensional and influenced by a range of factors, including a predisposition to trust tech- nology. The TIST model suggests that technology trust can be evaluated by assessing the technology's predictability, reliability, and utility and through con- sideration of the individual's predilection to trust Technology. Technology predictability is an individual's expec- tation of the technology consistency of performance based on past experiences and future expectations (10]. To assess technology predictability, the individual creates a summation of all past experiences with tech- nolagy and uses these appraisals to forecast how the technology will perform at a future point in time. In the context of trust in technology, predictability is based on an individual's ability to forecast that the technology will perform as expected. Technology reliability is an individual's confidence that the technology will consistently perior in situa- tions that involve some degree of dependence and risk In situations where individual depend on the tech- nology for the completion of a job-related task, the individual is placed in a position of vulnerability if the technology does not function as expected. This vulner- ability creates a dependence upon the technology: in other words, technology reliability is mast salient when successful jobs performance depends upon technology The success of implementing HRIS is predicated on organizational technological and human factors Understanding what determinants affect HRIS imple mentation success is important (45) since these factors can arise during all phases of the technology planning and installation process 46). Human factors such as user adaptation, acceptance, training, and on-going support are as critical as the technical aspects of the implementation process [47]. For example, Delane and McLean (48) have obinred an undated model of infor mation systems succes s ing that individual level variables such as system usage, system quality, and information quality influence the success of the organization's IT implementation initiative. As stated earlier, we propose that technology trust influences 4.1. Organizational determinants 4.1.1. Organizational trust and pooled interdepen- dence. Organizational trust is empirically distinguish- able from interpersonal trust 49, 50). Organizational trust is the extent to which arganizational members have a collectively held trast orientation toward the eenplaying firm (511. From this perspective, the trast assessment is applied to the organization as a whole and is independent af personal trust evaluations of selected firm menbers. Organizational social capital is a similar construct in that it also calls attention to the character of social relations within the firm (52). According to our conceptualization, organizational trust is lonely a product of cont rove nt social reputation, especially in the early stages of the enployee-organization relationship. When employees chowe to join a firm, they usually do so having und limited pre-employment interaction with organizational Journal of Information Science, 31 (5) 2005, pp. 340-352 CILIP, DOE: 10.1177/0165551505055399 343 344 Journal if Information Sa , 31 [5] 2005, P. 340353 CLIP, DOI: 10.11772 15555 15053553 S.K. LIPPERT AND PM. SWIERCZ Human resource Information systems Technological Technology ality Technology Usabile P2: + HRIS Technology Trust HRIS Implementation Interdependence is a reciprocal relationship between individuals or groups and is an analog to Thompson's pooled interdependence construct. For Thompson (5B). interdependence refers to the interconnection of work processes which can be classified into one of three categories: (11 pooled interdependence, where all objects of trust contribute to the overall goal: (2) sequential interdependence, where some inter actions are performed before then und (31 reciprocal interdependence, where elements are directly affected by others and must be considered simultaneously. Thompson (58) asserts that, in pooled interdependence, ench part of the organization makes a discrete contri- bution to the whole and is supported by the organiz ation. In situations of pooled interdependence, team members work independently and interdependence is anchored in the task for which they are collectively responsible [59]. Although Thompson's [58] conceptu- alization of pooled interdependence pre-dated the computer revolution, his insight hy with time been shown to be particularly prescient. HRIS success is highly dependent upon members of the referent group. in this case, the entire organization, trusting the technology. The most dramatic example of pooled interdependence is in situations where the employee uses the HRIS to self-input data. These observations on the constructs of organiz- ational trust and pooled interdependence lead to the following propositions regarding their relationship to HRIS technology trust sensitive information an HRIS technologies become more deeply embedded into the social fabric of an organization. In this sense, HRIS community membership behavior is analogous to voter participation in the political system. The combined act of making the decision to register as a voter and the act of voting are explicit statements of community membership and an expression of trust in the basic political system they represent. As an example, confidence in the voting technology as the United States learned from the 2000 Presidential election is intimately related to the workings of denocracy and confidence in citizenship. At a certain point, trust in technology becomes one of the mechanisms holding together the political com- munity whole. In a similar man, trust in the HRIS can be seen as being related to organizational community mainten- unce. Not trusting the HRIS will be costly for both members as individuals and for the entire organization. The individual casts af not insting the HRIS may be associated with decreased access to information. This potential deficiency of information may affect eenplayee efforts to enhance personal capital by com- pranising the knowledge nended for movement within the internal Inbour market. As such, employee access to broader organizational resources and rewards will be diminished. Costs associated with low levels of trust in the HRIS at the individual level are exacerbated at the organizational level since the costs became cumulative in nature. In ander to become fully engaged in HRIS implementation, both new and continuing employees need to experience an on-going sense of community membership. These notions lead to the following proposition PS: PIO: Predisposition Socializaton Sensitivity to Privacy Fig. 1. Model of technology trust in human resource information systems. Proposition 1. Higher levels of organizational trust lead to higher levels of HRIS technology trust. Proposition 2. Higher levels of pooled interdependence lead to higher levels of HRIS technology trust. Proposition 3. Higher levels of organizational con- munity lead to increased levels of HRIS technology trust. thernbers. This means they have not had an oppor- tunity to make a personal trust evaluation of the organization. For the typical new employee, assess ment of an organization's trustworthiness develops over time, and is necessary for effective social inter- action 52). The new employee develops an initial sense of tnast about the company based on past organiz- utional experiences and the current recruitment and selection process. Accepting a position is an expression of organizational trust even though it is unlikely to be explicitly acknowledged Over time, new employees revisit their trust judg- mnents through continul individual trust assessments 154 which increase or decrease their overall trust per ception about the organization. As part of this process, enployees are likely to examine the institutionalized mechanisms of coganizational social capital. For example, they will read the employee handbook more carefully, examine the performance appraisal and com- pensation systems looking to identify the beganiz- ational values and the performance behaviors that are rewarded and review the HR practices to assess their degree of involvement in decisions that will influence their career (55) Trust is a natural and essential component of all relationships (28, 56). The median position between never trust/always trust acknowledges the risks associ- ated with interdependence in any relationship 157] When the never trust/always trust dichotomy is rejected individuals consciously acknowledge the importance of the relationship between risk and inter- dependence. 4.1.2. Organizational community. An organizational Comenunity is a collective of individuals aligned around common interests, goals, principles, or goods. Building an organizational comienunity is an on-going process rather than a particular type of fixed organiz- ational structure. In organizations, community is the sense of belonging based on mutual interests, goals, and personal styles [60]. Community standards and membership rules offer privileges to members who occupy certain positions or exhibit community- sanctioned behaviors within the organization. An employee's purposeful interaction with the HRIS carries with it a statement of community membership since individuals are increasingly asked to provide 4.1.3. Organizational culture. A number of researchers have studied the relationship between organizational culture and trust (61, 62]. In fact, organizational culture is often defined as being composed of a number of elements, of which one is organizational trust. Organiz- ational culture reflects a corporation's fundamental beliefs about how it should function, its accepted nors of behavior and the path to achieving its goals 63-65). Trust can be manifested as part of culture through various behaviors that involve trust violations such as lying cheating, and steling gol. Elements of organizational trust involving honesty and credibility Journal of Information Science, 31 (5) 2005, pp. 340-353 @ CILIP, DOE: 10.1177/0165551505055399 345 Joumal of Information Science, 31 (5) 2005, pp. 340-353 CLIP, DOT: 10.1177/0165551505055399 S.K. LIPPERT AND P.M. SWIERCZ Human resource information systems Tabla 1 McLaughin and Skinner characteristics of management information systems applied to HRS and technology trust nology in the form of improved job performance, the result is a reinforcement of his adoption position Additionally, if an individual observes the technology performing well across multiple applications, his decision to continue using the new technology is further reinforced. Therefore, Component Description Connection to technology trust Chorkability This component is related to the tastability for technology reliability Proposition 5. Higher favorable technology adoption experiences will be positively related to higher trust in HRIS technology. Confidence The system has protocols for chocks and balances that ensure accuracy and verification of input and output data Users have confidence both in their capability in use the system and in the system itself Users have control over the operation of the system, particularly information supplied and this component is linked to technology predictability Control This component is connected to technology predictability Ease of use Speed Understanding can help facilitate information exchange by aligning individual and organizational goals [67, 6B]. Trast violations can occur at an individual level between organizational members and the organization itself 154). In this circumstance, transactions which occur between individunls and the organization are evaluated and aggregated to create an individually assessed tnast level [51]. One example of a trust violation might be changes in corporate policy perceived as insensitive to the needs and expectations of long-teren employees. For example, IBM's decision to change unilaterally its long-established pension plan for its US employees was widely viewed as a trust violation (G9). The cum- lative effect of each trust violation at the individual level is a loss of trust in the organization as an entity and an incremental change in the overall culture of the organisation Consistent with these expectations, a recent case study reported that the organizational culture of the Norwegian Army was a hindrance to successful IT adoption of a specialized Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) project. Talsby [70] found that the culture made it easy for the leadership to avoid taking responsibility for their decisions. This denial affected the leadership's ability to influence the behavior of their appointed groups. Likewise, additional studies have suggested that organizational culture impacts technology adoption 71-73), successful technology assimilation [74]. perceived user satisfaction [75, 76] and inter national technology transfer 77. In particular, Ruppel and Harrington [72] found that an organizational culture which emphasizes trast positively influences intranet implementation. These observations lead us to the following proposition: Users parceive the system as easy to use The system can be quickly and efficiently used "The system and its outputs aru sasily understandable to the user This component addresses technology utility this component is tied to technology reliability This component is related to technology reliability 4.2.2. Technology utility and technology usability. In recent years, scholars interested in understanding and managing technological innovation have become increasingly interested in the users' of new technology This stream of research is still in the early stages of development but has already allowed movement away from the traditional, albeit narrow approach of pre- senting technological change as a simple advance in operational performance made possible by advanced engineering (78). Today, scholars know much more about how the idiosyncratic attributes of specific organizational settings influence the use, character, and impact of what appear to be functionally equivalent technologies (79, 80). Based on user reactions to the introduction of a new management information system, McLaughin and Skinner (81) discovered a distinct difference between the concepts of utility and usability. Their research revealed that utility refers to the systeen's potential to neet performance expectations as designed by its man- agerial sponsors. In contrast, usability refers to how the system is experienced by actul unens. Utility is driven by engineering and economic concerns; usability is driven by personal and sociological issues. Top per- forming systerns require both high utility and high usability The McLaughin and Skinner tail research revealed six related but distinctive components of usability: (1) checkability: (2) confidence; al control; (4) case of use (5) Speed; and (6) understanding. Table 1 describes each of the six components and identifies its connection to technology trust. Checkahil- ity, speed and understanding are related to technology reliability since each component deals with issues of current system usage. Confidence and control relate to technology predictability since both components deal with the individual's expectations regarding how well (1) the types and quantity of information they are designed to cnpture and share; (2) the features of the technologies; (3) the design of the technologies; (41 the complexity of the technologies; and (5) the social dynamics among organizational members Without Careful considerntion of these factors, prac- titioners, organizational leaders, and scholars risk either underutilizing new HRIS technologies or over estigating their utility and usability. These abservations on the constructs of utility and usability lead to the following propositions: Proposition 4. Organizations with hish trust culture will experience higher degrees of trust in their HRIS technology. he will be able to control the technology in the future. Ease of use is connected to technology utility since its focus is on the degree to which individuals perceive the system as many to use. An additional insight gained from the McLaughin and Skinner (81) research is the process by which user evaluations can influence a technology sponsor's understanding of the system and influence how such systems are stabilized across an organization. In under standing this, it is important to be sensitive to the extent to which different referent and usergroups' defi- nitions of need, usability and usefulness are recognized by system designers and sponsors. The degree of perceived utility for a single tech- nology will differ depending upon the utilization context 82). For example, research has shown that mail produces a less rich interpersonal communication than face-to-face interactions 183, 84. Thus, if one seeks to use e-mail as a tool of communication, it will be discovered that e-mail is an excellent choice for exchanging data and information but a poor choice if the goal is an emotionally satisfying conversation Therefore, although e-mail technology is undoubtedly useful. usefulness in ultimately determined by the context in which it is employed. It is tempting to conclude that the substantial benefits of coninunication and information technolo- gies (a5] can seselessly migrate to HR applications However, the characteristics of new technologies to support HRIS in a meaningful way depend on a nurnber of different concerns including: Proposition G. Higher user perceptions of technology utility are positively related to HRIS technology trust. Proposition 7. Higher user perceptions of technology usability are positively related to HRIS technology trast. 4.2. Technological determinants 4.2.1. Technology adoption. Individuals seek rein forcement of their decision to adopt a technology by performing a series of on-going internal assessments These evaluations are achieved by examining personal assessments of one's satisfaction level with the tech- nology. If the individual is consistently satisfied with the new technology, he is not likely to reverse his earlier adoption decision. Additional reinforcement is realized as individuals begin consciously to recognize the benefits of the system. If the individual is able to personally experience the benefits of the new tech- 4.3. User determinants 4.3.1. Socialization. Socialization is the process by which a new organizational member acquires the knowl- edge, attitudes, and behavior required to participate with his peers and supervisor (16]. Corporate insiders can often aid new organizational menbers in their under- standing af how and what norms are exercised (87) Various strategies and tactics are used to socialize new eenployees through the learning process as they are accepted into the fire [88. Corporate values and atti- tudes are transferred to new employees during this gunal HE InftTatian Striant, 31 (5) 2005, P. 140-333 CLIP, DIY: 10. 1 01655550505533 Toumal af information Science, 31 (5) 2005, pp. 340-353 @ CILJP. DOI: 10.1177/0165551505055399 JIS Human resource information systems (HRIS) and technology trust Susan K. Lippert Department of Mosogonent, Lellow College of Business, Drexel Vaiversity, Philadelphia, USA Paul Michael Swiercz Department of Mosogonent Science, School of Business and Public Management. The George Washington Diversity, Washington DC, USA trust influence an individual level of trust in the TIRIS technology technology trust) and ultimately the wc of an HRIS Implementation price. A summary of the relationship between the key contracts in the model and recommendations for future research are provided Keywords: technology trust: human resource infor mation systems systems implementation; organi ational trust; pooled interdependence; ornnimational community; animational culture technology adaption technology utility technology usability: socialization; sensitivity to privacy: predisposition to trust Roxcavod 25 January 2005 Ruvised 10 March 2005 1. Introduction Abstract Scholars in many disciplines have considered the antecedents and on e of various forms of trust. This paper general 11 pmpositions exploring the relationship between Human Resource Information Systems (HRIS) and the trust an individual place in the animate technolon technology trust and models the effect of those relation- ships on HRIS Implementation Specifically rantatal, technological, and wer factors are con- sidered and modeled to rate a set of estable propesi- Bons that can subsequently be investigated in various rantaalweg. El propositions are offered su- proting that organizational trust pooled interdependence, rantatal c o ntrational culture, tech- molog adoptie, technology to technolo ability socialization, selvity to pracy, and predisposition to Hutan Resource Information Systems) CHRIS) imple mentation such as emr a significant chal lenge for organizations attempting to justify planned investments or recover expenses ociated with investments already incurred 1. In the information technology (IT) literature, a number of ons have been offered to explain implementation files Nonetheless, new determinants of implementation SUCCESS are required because the Editional explana tons - limited user intention 2. poor planning al. misation of technology to existing organisational business processes 14 and limited research -are inadequate in the face of the unique challenges associated with successful TRIS implementation SIA concurrent organizational challenge is the creation of performance metrics to the value-added contri bution of new HRIS initiatives 11.6L Suresful implementation of new and upgraded human resource information systems requires a more encompassing Correspondence de Susan K Lippert, Ph.D., Drul Uni- ursity. Lalow College of Business, Department of Manage munt 101 N. Srl, Room21, Philadelphia, PA 19104 Email: lippu l adu 340 Journal of Information Science, 31 (5) 2005. Pp. 340-353 CUP, DOI: 10.1177/01 SOSO5399 S.K. LIPPERT AND P.M. SWIERCZ Human resource information systems to understand how technology trust impacts employee engagement with the HRIS. The purpose of this paper is to generate a set of 11 propositions exploring the relationship between HRIS and technology trust and to posit the effect of these proposed relationships on HRIS implementation success. Specifically, organizational technological, and user factors are considered and mnadeled to generate 11 testable propositions that permit the empirical investigation in a range of organizational settings. The paper is organized into five section, Section 1 intraducns the topic and explains how the presentation is structured. Section 2 provides the theoretical grounding for linking HRIS implementation with tech- nology trast. The third section explores trust and its relationship to technology, In Section 4, 11 propositions are offered to illustrate the relationship between tech- nology trust and HRIS implementation success. The paper concludes with a summary of the relationship between the key variables of the model and recomenen- dations for future research. perspective because technologies allowing for sophisti- cated human capital management are essential for competitive success in the contemporary world economy [7]. A successful model of HRIS implementa- tion succes must consider an expanded range of factors likely to influence acceptance of deployed technologies (8). What is required is a perspective that is more conscious af and responsive to the social and operational demands of distributed IT at the micro level [9]. In response to this need, in this paper we dengnistute that the construct technology that offers considerable promise toward the effort to explain why HRIS implementation is too often less than fully Sacessful. Technology trust can be defined as an individual's willingness to be vulnerable to a technology based on person-specific expectations of the technology's pre- dictability, reliability, and utility as moderated by the individual's predisposition to trust the technology 110, 11]. As showcased in the propositions offered below, we believe that a more focused understanding af how technology trust relates to HRIS deployment offers the opportunity to develop a broader range of strategies to improve implementation initiatives. A contemporary HRIS is a dynamic database of demographic and performance information about each ernployee. It comprises software, hardware, and systematic procedures used to acquire, store, manipu- late, analyze, retrieve, and distribute pertinent infor mation about an organization's human resources 12 13). Data maintained in an HRIS can be used as a con- petitive information resource for virtually all core man- agement functions including planning. Organizing monitoring, controlling and leading 1141, HRIS tech- nology supports strategic planning through the genera tion of labour force supply and demand needs. requirements and forecast lis). An HRIS maintains information on recruitment, applicant qualifications job specifications, hiring procedures, organizational structures, professional development, training casts, performance evaluations, workforce diversity, and employee attrition (15). With well-functionins HRIS. employers can quickly respond to a changing con petitive landscape by developing targeted conpense- tion and recognition programa, making accurate salary forecasts, tailoring benefit programs, determining where to invest scarce training dollars and, arguably most importantly, redeploying key personnel as market conditions demand 116. Because organizational success in a knowledge economy is disproportionately dependent on employee performance (17], it is becoming increasingly important 2. Rationale for the model but also serves individual employees by enabling them to become self-sufficient and in greater control of their personal data. On the positive side, if the employee is able to see a benefit in using the system, he is more likely to be motivated to input timelyaccurate and comprehensive data (24). By providing employees with access to their personal employment record. self- administered HRIS can provide the immediate feedback and validation essential to effective motiva- tional program design. An HRIS with problems can have the opposite effect. Employee concerns about the security of their personal information remain an important expany and public policy issue. In a case in early 2005, ChoicePoint, an information data storage company discovered that the expected security of their HR infomation was widely companised, leading to personal and proprietary data being opened to the public domain [25]. An outcome of this recent case is the requirement to conduct a com- prehensive investigation to determine how the data were disclosed. When something like this happens technology that is negatively affected by the exposed vulnerability of systems that had been promoted as reliable and secure. The effect is a compromise of an individual's technology trust, an outcome with the potential to negatively impact eenplayee willingness to enter accurate and timely personal data in the future. Second, the inclusion of HR functionality within full-service software technologies places additional burdens on HR and IT personnel. In particular, the introduction of Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems has challenged HR and IT personnel to learn and integrate the wide range of functions embedded within these systems. ERP systems developed by SAP. PeopleSoft, Oracle, Bann, and Lawson conbine depart- ment operations, including the HR function, into an integrated software program running of a single database oftentimes stored on a secured web server. These web-based systems enable departments to share information in ways not anticipated three decades ago when early HRIS software first began to emerge. With un ERP market expected to expand from $19.8 billion in 2001 to $31.4 billion in 2006 1211. the number of parties - suppliers, vendars, customers and a wide array of secondary stakeholders- with a vested interest in HRIS performance success continues to grow. Third is the emergence of self-administered' or 'self- service' HR management as a trend with wide-ranging trust implications Research by the consulting fir Towers Perrin (22 reported that the number of com- panies using HR self-service applications tripled between 1999 and 2000. In addition, HR departments using the internet as the medium for a self-service HR function experienced a 38% gain in accumcy, a 50% reduction in HR staff worklands, and a 100% improve ment in timeliness 22). Employens using self-service functionality can easily update and verify personal information, consult online lists of intemal job vacancies, access corporate hand- books, and receive notices about upcoming training sessions (23). Managers can analyze job candidate profiles online, construct salary models, view benefits programs, monitor abannten trends and retrieve government labour regulations and forts for compli- ance purposes. In addition, individual eenplayee per formance, evaluation, and career development can all be accomplished through an HRIS. One by-product of this technological interface is that these systems empower employees in non-traditional ways. Employees now have continual access to their personal information as well as the responsibility of ensuring that data in the HRIS is accurate and complete. Organizational members at all levels can quickly and efficiently access data while managers and supervisors can use the information for decision- making Systems empower employees by enabling them to have 24/7 access to their critical personal infor- mation via a web-based HRIS [24]. An enterprise-wide HRIS not only makes the HR function more effective Three important trends are linked to the investigation of the relationship between technology trust and HRIS implementation sucx . Finit, the number of firms investing in HRIS has dramatically increased in recent years 5. Over the last two decades, organizations have grown increasingly dependent upon human resource (HR) systems to increase the effectiveness of human assets and provide management guidance. Addition- ally, HR-specific competitive pressures and regulatory requirements are no longer restricted to large organiz- ations but are now of concern to large, mid-level and small companies 18. New technologies and reduced casts have enabled companies, regardless of fire size, to purchase HR technologies S, 19. As a consequence, human resource information systems have evolved into sophisticated IT solutions designed to manage a wide variety of human resource data and to provide analyti- cal tools to assist management in HR decision-making 118). The financial risks associated with IT use by both large and small enterprises are of greater relevance not only due to direct technology acquisition costs but also due to the high implementation expenses associated with time away from productive work in the form of downtime or training (20). As such, understanding the factors that impact successful implementation has economic implications for all employers regardless of Organizational size. 3. Technology trust - expanding the notion of trust Understanding the role of technology trust in the HRIS implementation success formula offers significant promise for explaining a major component of the implementation process. The notion of trusting an inanimate object is not new. Writing from the perspec- tive of a communications theorist, Giffin (26) suggested the entity upon which the trust is bestowed can be a person, place, event, or object. Thus, in this paper, the 'object of trust is the HRIS. Muir 1271 pioneered the use of a behavioral perspec- tive by building upon the interpersonal trust viewpoint developed by Reenpel, Holmes, and mainta 1231. In series of publications, Muir and her colleagues (27.29 30] employed an interpersonal approach to better understand the nature of trust between humans and machines and to determine the factors affecting this one-sided trust relationship. As a consequence of this effort, she identified three common trust elements: (1) the description of trust as an expectation or confidence; Journal of Information Science, 31 (5) 2005, pp. 340-353 CHIP, DCX: 10.1177/0165551505055399 Journal of Information Science, 31 (5) 2005, pp. 340-353 CLIP, DOI: 10.1177/0165551505055399 S.K. LIPPERT AND P.M. SWIERCZ Human resource Information systems morphixed. Therefore, different measures are required to assess an individual's trust in technology. Third, both interpersonal trust and technology trust evaluations are made by the individual after each interaction with the object of trust, either another indi- vidual interpersonal trust) or a technology (technology trust). Fourth, both forms of trust represent an individual's perceptions about the object of trust influenced by his predisposition to trust in general. Predisposition to trust is the influence exerted on a trust referent based on an individual's generalized attitude toward trust. F or exuenple, an individual could have a high predisposition to trust technologies and exhibit this predilection by being the first to purchase and use a new system. Yet, this same person might not have an ATM card out of concern that the ATM technology may not dispense the corect amount of money from his checking account, with the similarities and differ- ences in mind, Lippert 110] developed a definition and model of Trust in Information Systems Technology (TIST) to articulate the new construct of technology (2) the focus of trust toward a specific person, place or object; and (a) the presence of multiple characteristics of trust referents. The first commannlity involves the definition of trust as an expectation or confidence addressed in croS disciplinary literature (31-37). A routine feature in these studies is the expectation of a future trust state. Trust as an expectation is tied to the notion that a tech- nolagv will function in a consistent manner at a future time leading to an individual's assessment that the technology is predictable. The second comenonality - the object of trust -is also resident in most trust definitions 33, 34, 36-39). The majority of these studies investigate trust between two individuals where the object of trust is another person. The object of interpersonal trast is the person while the focus of technology trust is the IT hardware and/or software. Trust is a state, perception, or con- dition that is directed or applied to a referent person object, or event. The third similarity identified by Muir 1271 is the multi-dimensionality of the trust construct. Trust is Composed of several chancteristies such as an entity's reliability, honesty, and motivation. In a similar vein. McKnight and Chervany (40) developed an attribute taxonomy of trust characteristics drawn from sixty sources across diverse disciplines. Their research identified additional examples of trust multi- dimensionality including: benevolence and honesty 138); ability, benevolence, and integrity (37l; and, pre- dictability, reliability, and faith (41). In a recent investigation focusing specifically on information technology, Lippert [42] confirmed that trusting a technology is different from trusting a human being. First, there is a difference in the directionality of the trusting relationship. When an individual trusts another person interpersonal trust), the relationship is bi-directional in that both individuals make a trust evaluation about the ather. By contrast, in a technology trust circumstance, trust is bestowed upon the tech- nalogy by the individual but the technology is incapable of trusting in retum 42). Second, in an interpersonal trust relationship, an individual can evaluate and measure the other person's trustworthiness by assessing the other person's ability. benevolence, and integrity [37]. The determinants used to assess an individual's trustworthiness are widely accepted contracts in the operationalization of interpersonal inast. However, when assessing an individual's trust in the technology, these same metrics are not useful even when the technology is anthropo- performance rather than solely upon personal pert::. Technology utility is an individual's faith, percep- tion, and assessment of the usefulness of the tech- nology. Faith, in this context is the belief that the technology will be consistently useful. Perceptions are initial cognitive and affective judgments derived from past experiences or information obtained from others regarding their experiences with the technology Assessments are final judgments made by the indi- vidual about the usefulness of a technology to enhance his job performance. Each of these constructs engenders a level ofinst in the information technology. Conpatible with this per spective, Rotter (43) suggests that everyone has a general predisposition to trust. Trust is applied to referent groups which are a collection of individuals linked through business, ideology, interest, geographic region or even gender or who share a set of canno characteristics 44). An individual may have a predis- position to not trust all members of a particular group but yet still trust ane person in that group 43) Far example, an individual may have very low inust toward home improvement contractors based on his past experiences tout encounters one contractor with whom he develops a trusting relationship. Rotter (43) con- cludes that each individual has a dynamic and very personalized sense of general trust. As such, predispor sition to trust technology is sustained through an indi- vidual's belief about the functioning of technology coupled with his expectations generalized to any and all technological systems. HRIS implementation success and that the relationship between technology trust and HRIS implementation Success may be influenced by a variety of techno- logical, arganizational and user issues. More specifically, the technological, organizational and user influences we propose as being important include organizational trust, pooled interdependence, community membership. organizational culture, technology adoption, technology utility, technology usability, cinlization, sensitivity to privacy and pre- disposition to trust. A graphic representation of these associations is offered in Figure 1 in the fom af a nadel of Enchnology trust in human resource infor mation systeens. The phenomena identified in the model can be explored first through development of propositions Crafted to permit the testing of both direction and intensity. The model in Figure 1 depicts 11 proposi- t ions leading to HRIS implementation success. The factors are organized into three categories: (1) beganiz- a tional; (2) technological; and (2) user. The proposed directionality for each relationship is noted next to the proposition number indicating an expected positive (+1 or negative (-) outcome. Each of the propositions and the associated logic are presented below. The HRIS implementation stage includes einployee orientation to the technology and evaluating assessments of usability and usefulness. Successful implementation is the outcome of the design, testing and deployment of the HRIS within an organizational setting. Technology trust is a framework for optimization of implementa- tiones. 4. Technology trust and HRIS implementation success According to the TIST model and consistent with Muir [27], technology that is conceptualized as being both multi-dimensional and influenced by a range of factors, including a predisposition to trust tech- nology. The TIST model suggests that technology trust can be evaluated by assessing the technology's predictability, reliability, and utility and through con- sideration of the individual's predilection to trust Technology. Technology predictability is an individual's expec- tation of the technology consistency of performance based on past experiences and future expectations (10]. To assess technology predictability, the individual creates a summation of all past experiences with tech- nolagy and uses these appraisals to forecast how the technology will perform at a future point in time. In the context of trust in technology, predictability is based on an individual's ability to forecast that the technology will perform as expected. Technology reliability is an individual's confidence that the technology will consistently perior in situa- tions that involve some degree of dependence and risk In situations where individual depend on the tech- nology for the completion of a job-related task, the individual is placed in a position of vulnerability if the technology does not function as expected. This vulner- ability creates a dependence upon the technology: in other words, technology reliability is mast salient when successful jobs performance depends upon technology The success of implementing HRIS is predicated on organizational technological and human factors Understanding what determinants affect HRIS imple mentation success is important (45) since these factors can arise during all phases of the technology planning and installation process 46). Human factors such as user adaptation, acceptance, training, and on-going support are as critical as the technical aspects of the implementation process [47]. For example, Delane and McLean (48) have obinred an undated model of infor mation systems succes s ing that individual level variables such as system usage, system quality, and information quality influence the success of the organization's IT implementation initiative. As stated earlier, we propose that technology trust influences 4.1. Organizational determinants 4.1.1. Organizational trust and pooled interdepen- dence. Organizational trust is empirically distinguish- able from interpersonal trust 49, 50). Organizational trust is the extent to which arganizational members have a collectively held trast orientation toward the eenplaying firm (511. From this perspective, the trast assessment is applied to the organization as a whole and is independent af personal trust evaluations of selected firm menbers. Organizational social capital is a similar construct in that it also calls attention to the character of social relations within the firm (52). According to our conceptualization, organizational trust is lonely a product of cont rove nt social reputation, especially in the early stages of the enployee-organization relationship. When employees chowe to join a firm, they usually do so having und limited pre-employment interaction with organizational Journal of Information Science, 31 (5) 2005, pp. 340-352 CILIP, DOE: 10.1177/0165551505055399 343 344 Journal if Information Sa , 31 [5] 2005, P. 340353 CLIP, DOI: 10.11772 15555 15053553 S.K. LIPPERT AND PM. SWIERCZ Human resource Information systems Technological Technology ality Technology Usabile P2: + HRIS Technology Trust HRIS Implementation Interdependence is a reciprocal relationship between individuals or groups and is an analog to Thompson's pooled interdependence construct. For Thompson (5B). interdependence refers to the interconnection of work procesStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

1 Expert Approved Answer

Step: 1 Unlock

Question Has Been Solved by an Expert!

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts

Step: 2 Unlock

Step: 3 Unlock