Question: please answer what ever you can! I really appreciate it! and much thumbs up The Colombian Peso (Foreign Currency Forecasting) The Colombian government had pegged

please answer what ever you can! I really appreciate it! and much thumbs up

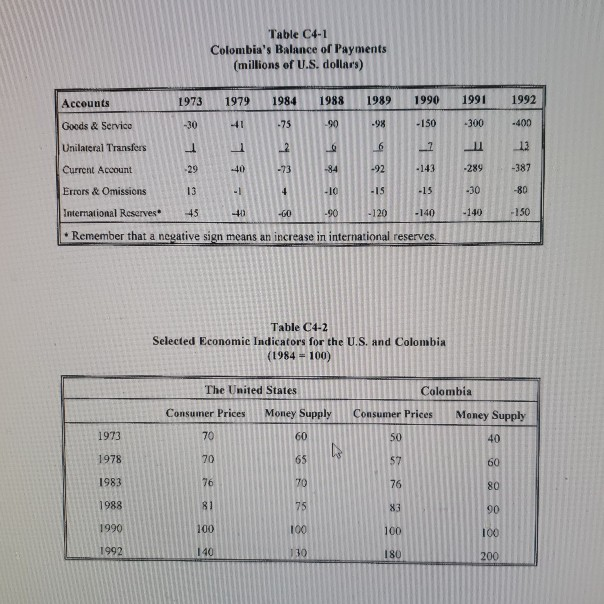

The Colombian Peso (Foreign Currency Forecasting) The Colombian government had pegged its peso to the U.S. dollar since its system of fixed, but adjustable, exchange rates (based on the 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement) collapsed in 1973. However, on June 2, 1993, Colombia unexpectedly announced its decision to devalue the peso close to 100 percent and to float the peso. This announcement was accompanied by more elaborate foreign exchange controls. The peso devaluation and the peso float, at first glance, seemed to have caused some serious problems for the International Products Corporation whose manufacturing facilities in Colombia depend heavily upon raw materials and components from the United States. An emergency meeting of the International Finance Committee was called on June 4 at 7:30 am to deal with the consequences of the devaluation and the float. Kevin Redlin, Vice President of Finance for South American operations of International Products, knew that all of the company's top executives would be attending the meeting and felt certain that he would be asked why the devaluation and the float had caught the company off guard. He decided to analyze economic statistics for both Colombia and the United States along with the news clippings in his file on the Colombian peso. Concern over the possibility of a devaluation had existed for years because, from 1973 to June 1, 1993, the exchange rate of 20 pesos per dollar had been artificially maintained through a variety of mechanisms. Exchange controls, import controls, and intervention were make the peso appear more stable than it was. These controls frustrated multinational companies with manufacturing operations in Colombia because many could not import crucial raw materials and components. Nevertheless, many analysts had not expected a devaluation until after the July 1993 meeting of Colombia's finance minister with representatives of a consortium bank. On the agenda was a discussion to reschedule S1 billion in overdue Colombian loan payments. Moreover, some observers felt that a bumper coffee crop and higher coffee prices might improve the country's balance of payments to such an extent that devaluation would not be necessary. Mr. Redlin was, therefore, not the only person caught off guard by the size of the devaluation and by the timing of the float. When Colombian Central Bank opened on Tuesday, June 2, it began quoting pesos at about 50,0263 per peso or 38 pesos per dollar as compared with the June I value of $0.05 per peso or 20 pesos per dollar. By Wednesday, foreign exchange experts had become sharply divided on how far the peso might fall. Some said that the foreign exchange market had already overreacted, while others saw no end in sight to the peso's depreciation Analysts also disagreed whether the devaluation and the float would be sufficient to correct the country's balance- of payments difficulties. All these conflicting the perplexing points of view made it more difficult for Mr. Redlin to assess the effects of the float and of the newly imposed exchange controls on his company's operations in Colombia By March 1993, rumors of an imminent devaluation of the peso were widespread. Although the same exchange rate of $0.05 per peso had been maintained for about 20 years, this was not the first time that rumors of a devaluation had surfaced, rumors had cropped up periodically for years, especially around the spring time. But this time, there were a number of reasons for apprehension Colombia's growing trade delicits and an inflation rate (at least twice the rate of the United States) had prompted international treasurers and bankers to conclude that a devaluation of the peso was inevitable. The The Columbian Peso annual growth rate of the country's money supply had been more than three times that of the United States in recent years. The spread between official and free market exchange rates had skyrocketed since November 1992. Many wealthy Colombians had moved large sums of money from Colombia into the United States and other foreign countries. Finally, for 1992 the difference between the U.S. interest rate and the Colombian interest rate ranged up to 8 percent in favor of the peso, but the forward discount rate for the peso ranged up to 20 percent Market analysts, including Mr. Redlin, agreed that the peso was overvalued in dollar terms. However, the size of the devaluation and the timing of the float came as a surprise to even the most sophisticated international treasurers and bankers. Colombia's ongoing success in obtaining large sums of money to finance its huge current account deficits indicated that the country could defend the exchange rate of 20 pesos per dollar. In may 1993, for example, Colombia borrowed $200 million from a group of European banks, thus making its total foreign des close to $10 billion. In fact, the country's international reserves had recently increased though its current account had been consistently negative. Second, many international treasurers and bankers said that Colombia did not have unused productive capacity sufficient enough to capitalize on a lower exchange rate. Moreover, favorable international economic conditions and reasonably promising growth for Colombian exports (higher-value exports of coffee in particular) had steadily narrowed the discounts on forward pesos since early April 1993. The country's finance minister had repeatedly denied rumors that a devaluation of the peso was imminent: in fact, the latest denial was issued on May 28, just a few days before the government announcement to float the peso on June 2 Table C4-1 Colombia's Balance of Payments (millions of U.S. dollars) 1973 1979 1989 1990 1992 -400 Accounts Goods & Service Unilateral Transfers Current Account Errors & Omissions International Reserves Remember that a negative sign means an increase in international reserves. Table C4-2 Selected Economic Indicators for the U.S. and Colombia (1984 = 100) Colombia The United States Consumer Prices Money Supply Consumer Prices Money Supply Questions: 1. Do you think that the peso has fallen far enough or that it will continue to lose value? (Hint: answer this question using the purchasing power parity theory) 2. Could the peso float have been forecasted? (Hint: answer this question using such economic indicators as the balance of payments, international reserves, inflation, money supply, and official versus market rates.) 3. How can you be sure that many wealthy Colombians had moved large amounts of money out of their country? (Hint: One of the items in Table C4-1 may shed some light on this question.) 4. The discrepancy between the interest differential and the forward discount rate for the peso in 1992 seemed to open incentives for arbitrage. Could it have been possible to take advantage of the opportunity for covered interest arbitrage? 5. What alternatives are available to the Colombian government for dealing with its balance-of- payments problems? 6. Briefly outline courses of action that International Products should take to cope with the foreign exchange controls (Remember that the company's manufacturing facilities in Colombia depend heavily on raw materials and components form the United States.) Note: This is a fictitious case and draws heavily upon the following two cases: Richard Moxon, "The Mexican Peso," in Gunter Dufey and lan H. Giddy, ed. 50 Cases in International Finance, Reading, MA Addison-Wesley, 1983. pp. 138-149, and John D. Daniels and Lee H. Radebaugh, "The Mexican Peso," International Business, Reading, MA Addison-Wesley. 1992, pp. 259-264

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts