Question: please do not write your opinion, write everything from the article. QUESTION 1- WHAT DID FRANK DO THAT DEMONSTRATED HIS EFFECTIVENESS AS A MANAGER? QUESTION

please do not write your opinion, write everything from the article.

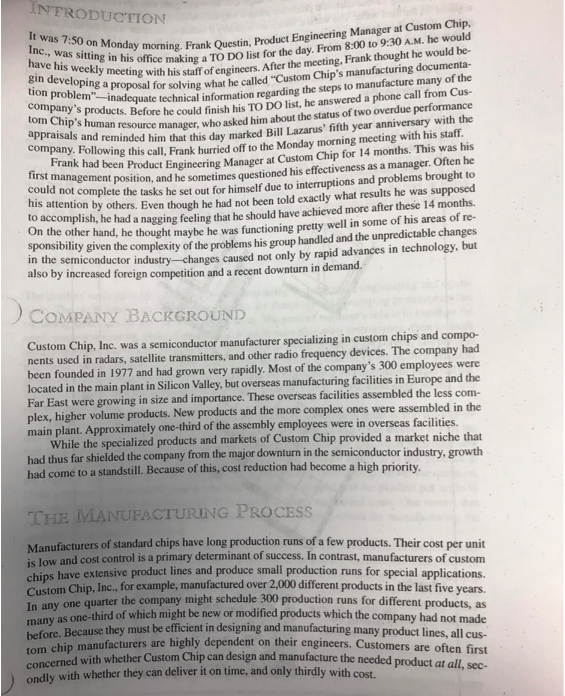

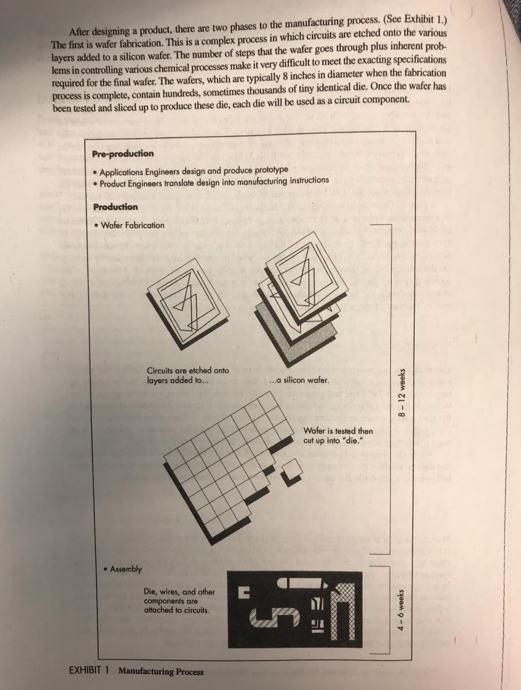

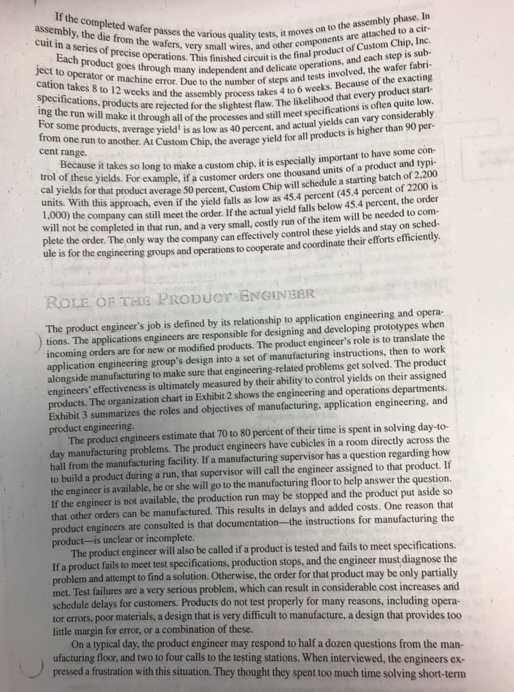

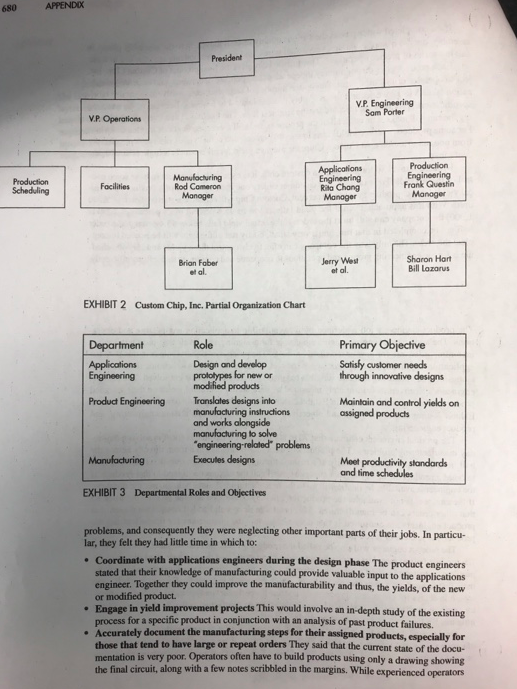

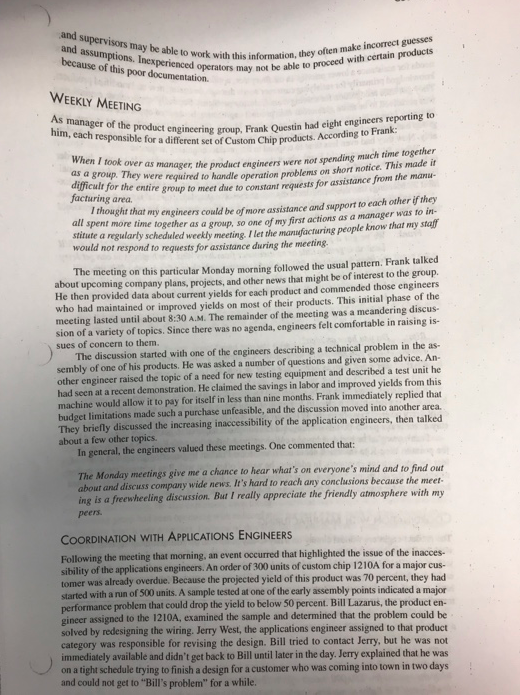

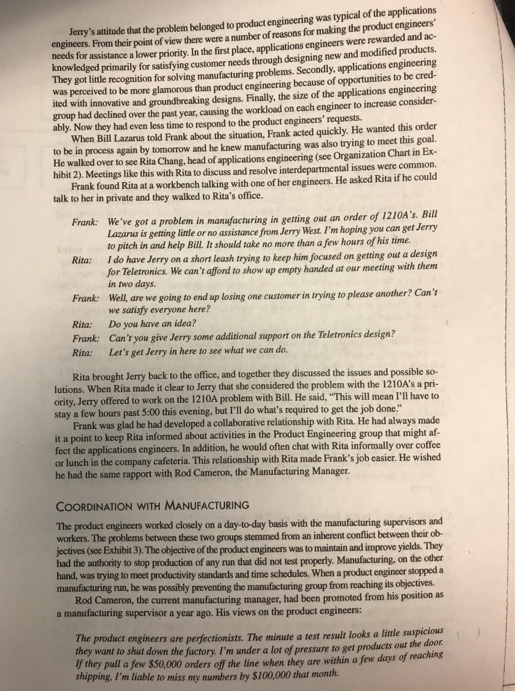

QUESTION 1- WHAT DID FRANK DO THAT DEMONSTRATED HIS EFFECTIVENESS AS A MANAGER? QUESTION 2- WHAT DID FRANK DO THAT YOU CONSIDERED TO BE INEFFECTIVE? QUESTION 3- USING MINTZBERG'S FRAMEWORK OF MANAGERIAL ROLES, RATE FRANK (USING 1 FOR WORST, 5 FOR BEST). A. LIAISON B. FIGUREHEAD C. LEADER D. DISSEMINATOR E. MONITOR F. SPOKESPERSON G. ENTREPRENUER H. DISTURBANCE HANDLER I. RESOURCE ALLOCATOR J. NEGOTIATOR GIVE EXAMPLES TO SUPPORT YOUR RATING QUESTION 4 - WHAT RECOMMENDATIONS WOULD YOU MAKE TO FRANK IN ORDER FOR HIM TO INCREASE HIS EFFECTIVENESS AS A MANGER? It was 7:50 on Monday morning. Frank Questin, Product Engineering Manager at Custom Chip. Inc., was sitting in his office making a TO DO list for the day. From 8:00 to 9:30 A.M. he would have his weekly meeting with his staff of engineers. After the meeting. Frank thought he would be gin developing a proposal for solving what he called "Custom Chip's manufacturing documenta- tion problem"-inadequate technical information regarding the steps to manufacture many of the company's products. Before he could finish his TO DO list, he answered a phone call from Cus- tom Chip's human resource manager, who asked him about the status of two overdue performance INTRODUCTION company. Following this call , Frank hurried off to the Monday morning meeting with his staff, first management position, and he sometimes questioned his effectiveness as a manager. Often he could not complete the tasks he set out for himself due to interruptions and problems brought to his attention by others. Even though he had not been told exactly what results he was supposed to accomplish, he had a nagging feeling that he should have achieved more after these 14 months. On the other hand, he thought maybe he was functioning pretty well in some of his areas of re- sponsibility given the complexity of the problems his group handled and the unpredictable changes in the semiconductor industry-changes caused not only by rapid advances in technology, but also by increased foreign competition and a recent downturn in demand. COMPANY BACKGROUND Custom Chip, Inc. was a semiconductor manufacturer specializing in custom chips and compo- nents used in radars, satellite transmitters, and other radio frequency devices. The company had been founded in 1977 and had grown very rapidly. Most of the company's 300 employees were located in the main plant in Silicon Valley, but overseas manufacturing facilities in Europe and the Far East were growing in size and importance. These overseas facilities assembled the less com- plex, higher volume products. New products and the more complex ones were assembled in the main plant. Approximately one-third of the assembly employees were in overseas facilities. While the specialized products and markets of Custom Chip provided a market niche that had thus far shielded the company from the major downturn in the semiconductor industry, growth had come to a standstill. Because of this, cost reduction had become a high priority. THE MANUFACTURING PROCESS Manufacturers of standard chips have long production runs of a few products. Their cost per unit is low and cost control is a primary determinant of success. In contrast, manufacturers of custom chips have extensive product lines and produce small production runs for special applications. Custom Chip, Inc., for example, manufactured over 2,000 different products in the last five years. In any one quarter the company might schedule 300 production runs for different products, as many as one-third of which might be new or modified products which the company had not made before. Because they must be efficient in designing and manufacturing many product lines, all cus- tom chip manufacturers are highly dependent on their engineers. Customers are often first concerned with whether Custom Chip can design and manufacture the needed product at all, sec- ondly with whether they can deliver it on time, and only thirdly with cost. After designing a product, there are two phases to the manufacturing process. (See Exhibit 1.) The first is wafer fabrication. This is a complex process in which circuits are etched onto the various layers added to a silicon wafer. The number of steps that the wafer goes through plus inherent prob- lems in controlling various chemical processes make it very difficult to meet the exacting specifications required for the final wafer. The wafers, which are typically 8 inches in diameter when the fabrication process is complete, contain hundreds, sometimes thousands of tiny identical die. Once the wafer has been tested and sliced up to produce these die, cach die will be used as a circuit component Pre-production Applications Engineers design and produce prototype Product Engineers translate design into manufacturing instructions Production Wafer Fabrication Circuits are etched onto layers added to... ...o silicon wofer. 8-12 weeks Wofer is tested then cut up into die." Assembly E Die, wires, and other components are attached to circuits. 2008 4-6 weeks SI EXHIBITI Manufacturing Process assembly, the die from the wafers, very small wires, and other components are attached to a cir If the completed wafer passes the various quality tests, it moves on to the assembly phase. In cuit in a series of precise operations. This finished circuit is the final product of Custom Chip, Inc. ject to operator or machine error. Due to the number of steps and tests involved, the wafer fabri Each product goes through many independent and delicate operations, and each step is sub cation takes 8 to 12 weeks and the assembly process takes 4 to 6 weeks. Because of the exacting Specifications, products are rejected for the slightest flaw. The likelihood that every product start- ing the run will make it through all of the processes and still meet specifications is often quite low, For some products, average yield' is as low as 40 percent, and actual yields can vary considerably from one run to another. At Custom Chip, the average yield for all products is higher than 90 per cent range. trol of these yields. For example, if a customer orders one thousand units of a product and typi- Because it takes so long to make a custom chip, it is especially important to have some con cal yields for that product average 50 percent, Custom Chip will schedule a starting batch of 2,200 units. With this approach, even if the yield falls as low as 45.4 percent (45.4 percent of 2200 is 1.000) the company can still meet the order. If the actual yield falls below 45.4 percent, the order will not be completed in that run, and a very small, costly run of the item will be needed to com plete the order. The only way the company can effectively control these yields and stay on sched- ule is for the engineering groups and operations to cooperate and coordinate their efforts efficiently. ROLE OF THE PRODUCT ENGINEAR The product engineer's job is defined by its relationship to application engineering and opera tions. The applications engineers are responsible for designing and developing prototypes when incoming orders are for new or modified products. The product engineer's role is to translate the application engineering group's design into a set of manufacturing instructions, then to work alongside manufacturing to make sure that engineering-related problems get solved. The product engineers' effectiveness is ultimately measured by their ability to control yields on their assigned products. The organization chart in Exhibit 2 shows the engineering and operations departments. Exhibit 3 summarizes the roles and objectives of manufacturing, application engineering, and product engineering The product engineers estimate that 70 to 80 percent of their time is spent in solving day-to- day manufacturing problems. The product engineers have cubicles in a room directly across the hall from the manufacturing facility. If a manufacturing supervisor has a question regarding how to build a product during a run, that supervisor will call the engineer assigned to that product. If the engineer is available, he or she will go to the manufacturing floor to help answer the question, If the engineer is not available, the production run may be stopped and the product put aside so that other orders can be manufactured. This results in delays and added costs. One reason that product engineers are consulted is that documentation-the instructions for manufacturing the product is unclear or incomplete. The product engineer will also be called if a product is tested and fails to meet specifications. If a product fails to meet test specifications, production stops, and the engineer must diagnose the problem and attempt to find a solution. Otherwise, the order for that product may be only partially met. Test failures are a very serious problem, which can result in considerable cost increases and schedule delays for customers. Products do not test properly for many reasons, including opera- tor errors, poor materials, a design that is very difficult to manufacture, a design that provides too little margin for error, or a combination of these. On a typical day, the product engineer may respond to half a dozen questions from the man- ufacturing floor, and two to four calls to the testing stations. When interviewed, the engineers ex- pressed a frustration with this situation. They thought they spent too much time solving short-term 680 APPENDIX Presiden President V.P. Engineering Som Porter V.P. Operations Production Scheduling Manufacturing Rod Cameron Manager Facilities Production Engineering Frank Questin Manager Applications Engineering Rita Chong Manager Brian Faber et al. Jerry West et al. Sharon Hort Bill Lazarus EXHIBIT 2 Custom Chip, Inc. Partial Organization Chart Department Applications Engineering Primary Objective Satisfy customer needs through innovative designs Product Engineering Role Design and develop prototypes for new or modified products Translates designs into manufacturing instructions and works alongside manufacturing to solve "engineering-related problems Execules designs Maintain and control yields on assigned products Manufacturing Moet productivity standards and time schedules EXHIBIT 3 Departmental Roles and Objectives problems, and consequently they were neglecting other important parts of their jobs. In particu- lar, they felt they had little time in which to: Coordinate with applications engineers during the design phase The product engineers stated that their knowledge of manufacturing could provide valuable input to the applications engineer. Together they could improve the manufacturability and thus, the yields, of the new or modified product Engage in yield improvement projects This would involve an in-depth study of the existing process for a specific product in conjunction with an analysis of past product failures. Accurately document the manufacturing steps for their assigned products, especially for those that tend to have large or repeat orders They said that the current state of the docu- mentation is very poor. Operators often have to build products using only a drawing showing the final circuit, along with a few notes scribbled in the margins. While experienced operators because of this poor documentation WEEKLY MEETING and supervisors may be able to work with this information, they often make incorrect guesses and assumptions. Inexperienced operators may not be able to proceed with certain products As manager of the product engineering group, Frank Questin had eight engineers reporting to him, each responsible for a different set of Custom Chip products. According to Frank: When I took over as manager, the product engineers were not spending much time together difficult for the entire group to meet due to constant requests for assistance from the manu- as a group. They were required to handle operation problems on short notice. This made ir facturing area. I thought that my engineers could be of more assistance and support to each other if they all spent more time together as a group, so one of my first actions as a manager was to in stitute a regularly scheduled weekly meeting. I let the manufacturing people know that my staff would not respond to requests for assistance during the meeting. The meeting on this particular Monday morning followed the usual pattern. Frank talked about upcoming company plans, projects, and other news that might be of interest to the group. He then provided data about current yields for each product and commended those engineers who had maintained or improved yields on most of their products. This initial phase of the meeting lasted until about 8:30 A.M. The remainder of the meeting was a meandering discus- sion of a variety of topics. Since there was no agenda, engineers felt comfortable in raising is- sues of concern to them. The discussion started with one of the engineers describing a technical problem in the as- sembly of one of his products. He was asked a number of questions and given some advice. An- other engineer raised the topic of a need for new testing equipment and described a test unit he had seen at a recent demonstration. He claimed the savings in labor and improved yields from this machine would allow it to pay for itself in less than nine months. Frank immediately replied that budget limitations made such a purchase unfeasible, and the discussion moved into another area. They briefly discussed the increasing inaccessibility of the application engineers, then talked about a few other topics. In general, the engineers valued these meetings. One commented that: The Monday meetings give me a chance to hear what's on everyone's mind and to find out about and discuss company wide news. It's hard to reach any conclusions because the meet ing is a freewheeling discussion. But I really appreciate the friendly atmosphere with my peers. COORDINATION WITH APPLICATIONS ENGINEERS Following the meeting that morning, an event occurred that highlighted the issue of the inacces sibility of the applications engineers. An order of 300 units of custom chip 1210A for a major cus- tomer was already overdue. Because the projected yield of this product was 70 percent, they had started with a run of 500 units. A sample tested at one of the early assembly points indicated a major performance problem that could drop the yield to below 50 percent. Bill Lazarus, the product en- gineer assigned to the 1210A, examined the sample and determined that the problem could be solved by redesigning the wiring. Jerry West, the applications engineer assigned to that product category was responsible for revising the design. Bill tried to contact Jerry, but he was not immediately available and didn't get back to Bill until later in the day, Jerry explained that he was on a tight schedule trying to finish a design for a customer who was coming into town in two days and could not get to "Bill's problem" for a while. Jenry's attitude that the problem belonged to product engineering was typical of the applications engineers. From their point of view there were a number of reasons for making the product engineers' needs for assistance a lower priority. In the first place, applications engineers were rewarded and ac knowledged primarily for satisfying customer needs through designing new and modified products. They got little recognition for solving manufacturing problems. Secondly, applications engineering was perceived to be more glamorous than product engineering because of opportunities to be cred- ited with innovative and groundbreaking designs. Finally, the size of the applications engineering group had declined over the past year, causing the workload on each engineer to increase consider ably. Now they had even less time to respond to the product engineers' requests. When Bill Lazarus told Frank about the situation, Frank acted quickly. He wanted this order to be in process again by tomorrow and he knew manufacturing was also trying to meet this goal. He walked over to see Rita Chang, head of applications engineering (see Organization Chart in Ex- hibit 2). Meetings like this with Rita to discuss and resolve interdepartmental issues were common. Frank found Rita at a workbench talking with one of her engineers. He asked Rita if he could talk to her in private and they walked to Rita's office. Frank: We've got a problem in manufacturing in getting out an order of 1210A's. Bill Lazarus is getting linle or no assistance from Jerry West. I'm hoping you can get Jerry to pitch in and help Bill. It should take no more than a few hours of his time. Rita: I do have Jerry on a short leash trying to keep him focused on getting out a design for Teletronics. We can't afford to show up empty handed at our meeting with them in two days. Frank: Well, are we going to end up losing one customer in trying to please another? Can't we satisfy everyone here? Do you have an idea? Frank: Can't you give Jerry some additional support on the Teletronics design? Let's get Jerry in here to see what we can do Rita: Rita: Rita brought Jerry back to the office, and together they discussed the issues and possible so- lutions. When Rita made it clear to Jerry that she considered the problem with the 1210A's a pri- ority, Jerry offered to work on the 1210A problem with Bill. He said, "This will mean I'll have to stay a few hours past 5:00 this evening, but I'll do what's required to get the job done." Frank was glad he had developed a collaborative relationship with Rita. He had always made it a point to keep Rita informed about activities in the Product Engineering group that might af- feet the applications engineers. In addition, he would often chat with Rita informally over coffee or lunch in the company cafeteria. This relationship with Rita made Frank's job easier. He wished he had the same rapport with Rod Cameron, the Manufacturing Manager. COORDINATION WITH MANUFACTURING The product engineers worked closely on a day-to-day basis with the manufacturing supervisors and workers. The problems between these two groups stemmed from an inherent conflict between their ob- jectives (see Exhibit 3). The objective of the product engineers was to maintain and improve yields. They had the authority to stop production of any run that did not test properly. Manufacturing, on the other hand, was trying to meet productivity standards and time schedules. When a product engineer stopped a manufacturing run, he was possibly preventing the manufacturing group from reaching its objectives Rod Cameron, the current manufacturing manager, had been promoted from his position as a manufacturing supervisor a year ago. His views on the product engineers: The product engineers are perfectionists. The minute a test result looks a little suspicious they want to shut down the factory. I'm under a lot of pressure to get products out the door If they pull a few $50,000 orders off the line when they are within a few days of reaching shipping. I'm liable to miss my numbers by $100,000 that month. Besides that, they are doing a lousy job of documenting the manufacturing steps. I've got a lot of turnover and my new operators need to be told or shown exactly what to do for each product. The instructions for a lot of our products are a joke. At first, Frank found Rod very difficult to deal with. Rod found fault with the product engia neers for many problems and sometimes seemed rude to Frank when they talked. For example, Rod might tell Frank to "make it quick, I haven't got much time." Frank tried not to take Rod's actions personally and through persistence was able to develop a more amicable relationship with him. According to Frank: Sometimes, my people will stop work on a product because it doesn't meet test results at that stage of manufacturing. If we study the situation, we might be able to maintain yields or even save an entire run by adjusting the manufacturing procedures. Rod tries to bully me into changing my engineers' decisions. He yells at me or criticizes the competence of my people, but I don't allow his temper or ravings to influence my best judgment in a situation. My strat egy in dealing with Rod is to try not to respond defensively to him. Eventually he cools down, and we can have a reasonable discussion of the situation. Despite this strategy, Frank could not always resolve his problems with Rod. On these occa- sions, Frank took the issue to his own boss, Sam Porter, the Vice President in charge of engi- neering. However, Prank was not satisfied with the support he got from Sam. Frank said: Sam avoids confrontations with the Operations VP. He doesn't have the influence or clout with the other VPs or the president to do justice to engineering 's needs in the organization. Early that afternoon, Frank again found himself trying to resolve a conflict between engi- neering and manufacturing. Sharon Hart, one of his most effective product engineers was re- sponsible for a series of products used in radars--the 3805A-3808A series. Today she had stopped a large run of 3806A's. The manufacturing supervisor, Brian Faber, went to Rod Cameron to com- plain about the impact of this stoppage on his group's productivity. Brian felt that yields were low on that particular product because the production instructions were confusing to his operators, and that even with clearer instructions, his operators would need additional training to build it satisfactorily. He stressed that the product engineer's responsibility was to adequately document the production instructions and provide training. For these reasons, Brian asserted that product en gineering, and not manufacturing, should be accountable for the productivity loss in the case of these 3806A's. Rod called Frank to his office, where he joined the discussion with Sharon, Brian, and Rod. After listening to the issues, Frank conceded that product engineering had responsibility for doc- umenting and training. He also explained, even though everyone was aware of it, that the product engineering group had been operating with reduced staff for over a year now, so training and doc- umentation were lower priorities. Because of this staffing situation, Frank suggested that manu facturing and product engineering work together and pool their limited resources to solve the documentation and training problem. He was especially interested in using a few of the long-term experienced workers to assist in training newer workers. Rod and Brian opposed his suggestion. They did not want to take experienced operators off of the line because it would decrease pro- ductivity. The meeting ended when Brian stormed out, saying that Sharon had better get the 3806A's up and running again that morning. Frank was particularly frustrated by this episode with manufacturing. He knew perfectly well that his group had primary responsibility for documenting the manufacturing steps for each prod- uct. A year ago he told Sam Porter that the product engineers needed to update and standardize all of the documentation for manufacturing products. At that time, Sam told Frank that he would support his efforts to develop the documentation but would not increase his staff. In fact, Sam had withheld authorization to fill a recently vacated product engineering slot. Frank was reluctant to push the staffing issue because of Sam's adamant stance on reducing costs. "Perhaps," Frank DIX thought, "if I develop a proposal clearly showing the benefits of a documentation program in man- ufacturing and detailing the steps and resources required to implement the program, I might be able to convince Sam to provide us with more resources." But Frank could never find the time to de- velop that proposal. And so he remained frustrated. LATER IN THE DAY Frank was reflecting on the complexity of his job when Sharon came to the doorway to see if he had a few moments. Before he could say "come in," the phone rang. He looked at the clock. It was 4:10 P.M. Rita was on the other end of the line with an idea she wanted to try out on Frank, so Frank said he could call her back shortly. Sharon was upset and told him that she was thinking of quit- ting because the job was not satisfying for her. Sharon said that although she very much enjoyed working on yield improvement projects, she could find no time for them. She was tired of the applications engineers acting like "prima don- nas," too busy to help her solve what they seemed to think were mundane day-to-day manufac- turing problems. She also thought that many of the day-to-day problems she handled wouldn't exist if there was enough time to document manufacturing procedures to begin with. Frank didn't want to lose Sharon, so he tried to get into a frame of mind where he could be empathetic to her. He listened to her and told her that he could understand her frustration in this situation. He told her the situation would change as industry conditions improved. He told her that he was pleased that she felt comfortable in venting her frustrations with him, and he hoped she would stay with Custom Chip. After Sharon left, Frank realized that he had told Rita that he would call back. He glanced at the TO DO list he had never completed and realized that he hadn't spent time on his top priority- developing a proposal relating to solving the documentation problem in manufacturing. Then, he remembered that he had forgotten to acknowledge Bill Lazarus' fifth year anniversary with the com- pany. He thought to himself that his job felt like a roller coaster ride, and once again he pondered his effectiveness as a manager. ENDNOTE 1. Yield refers to the ratio of finished products that meet specifications relative to the number that initially entered the manufacturing processStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

1 Expert Approved Answer

Step: 1 Unlock

Question Has Been Solved by an Expert!

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts

Step: 2 Unlock

Step: 3 Unlock