Question: Please read the case study below and answer the following: 1. Who should be blamed for the failure of the projects in this case study?

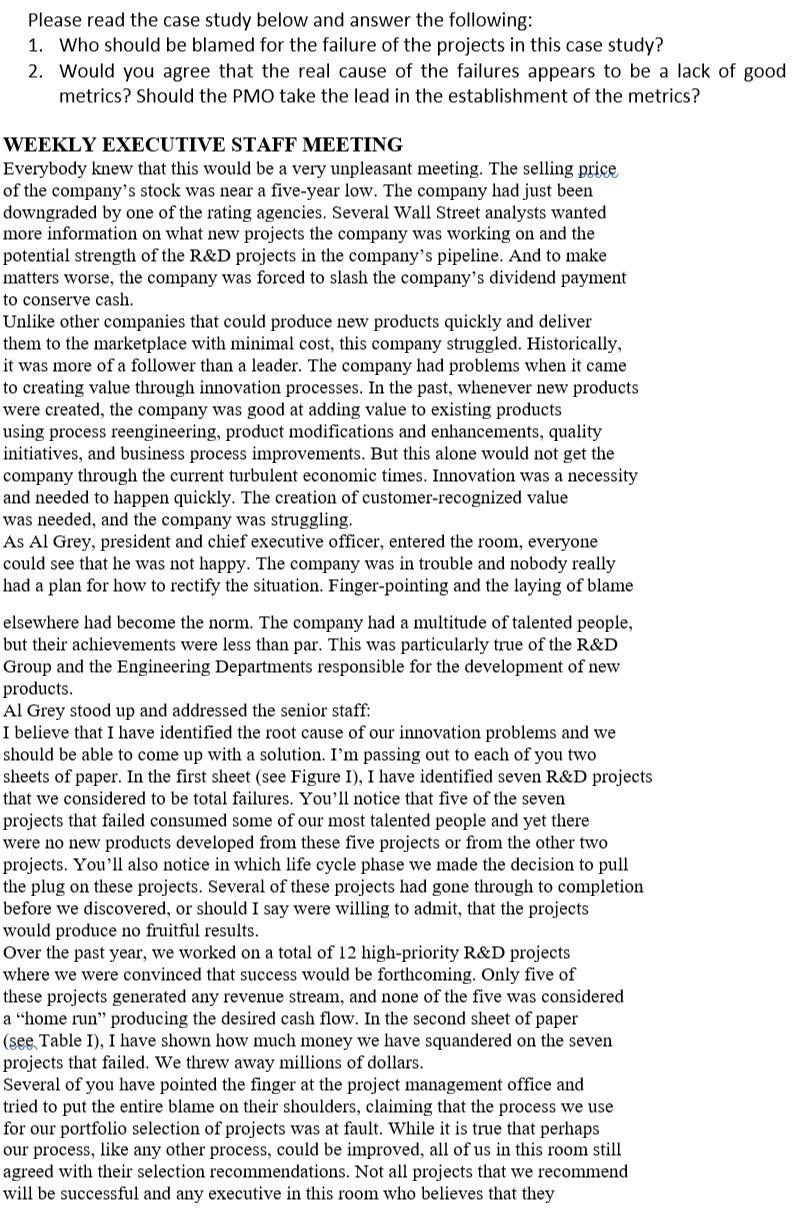

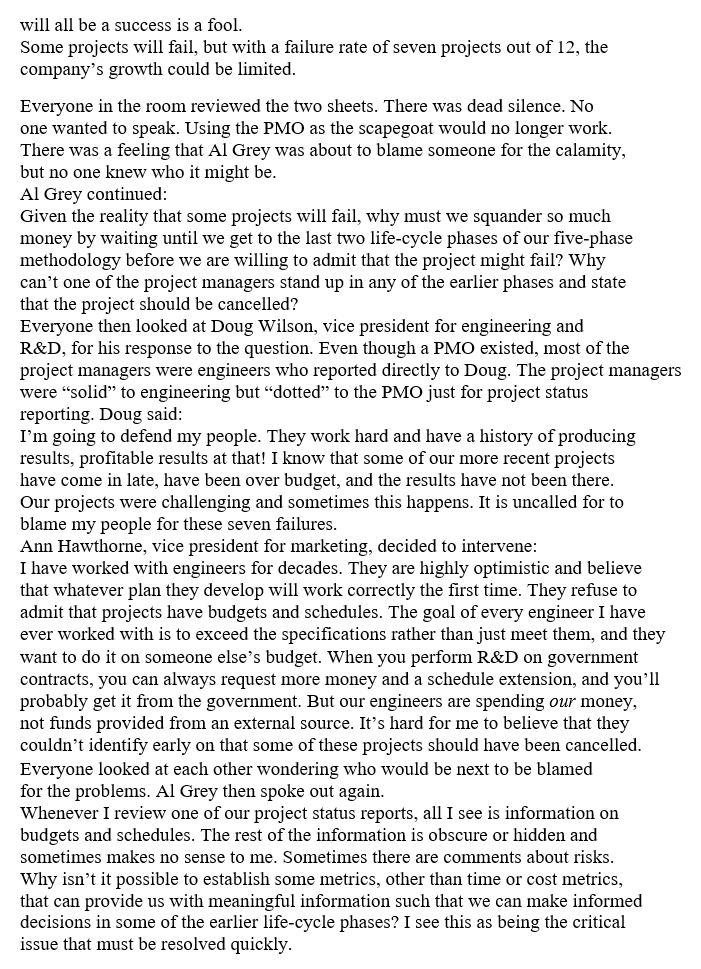

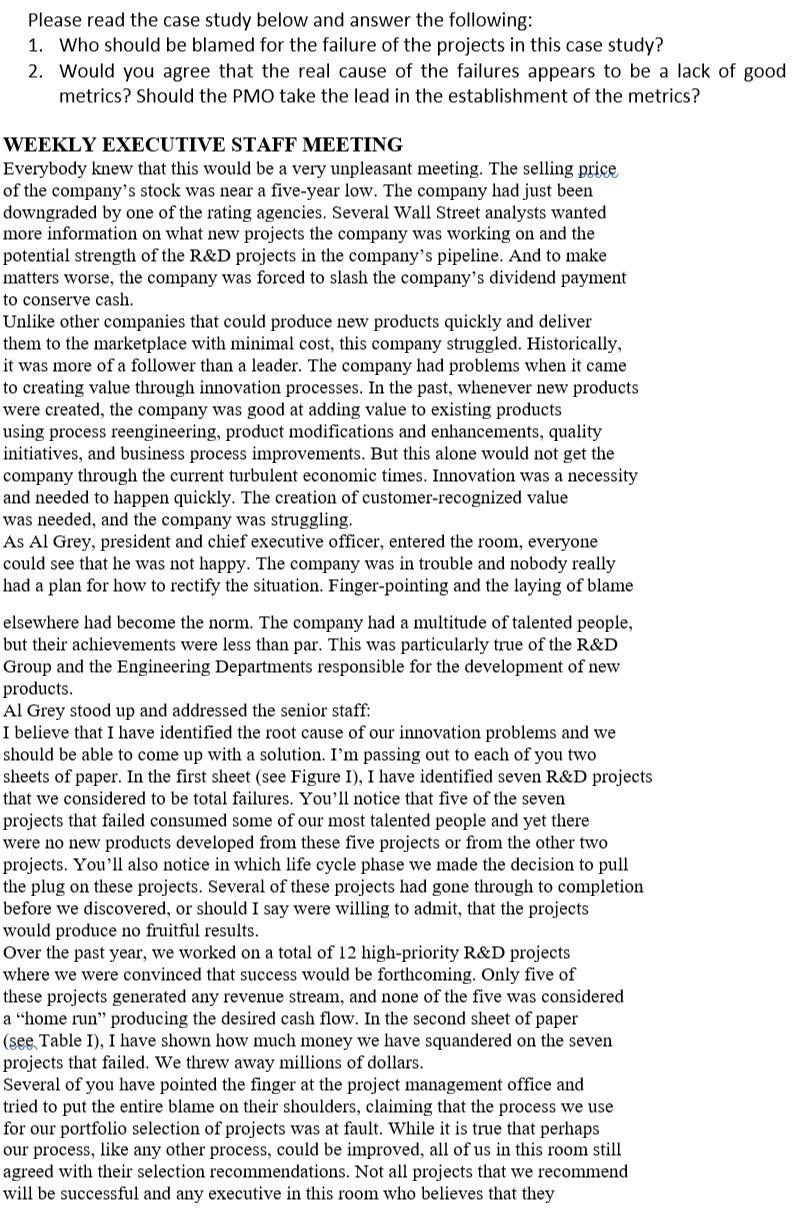

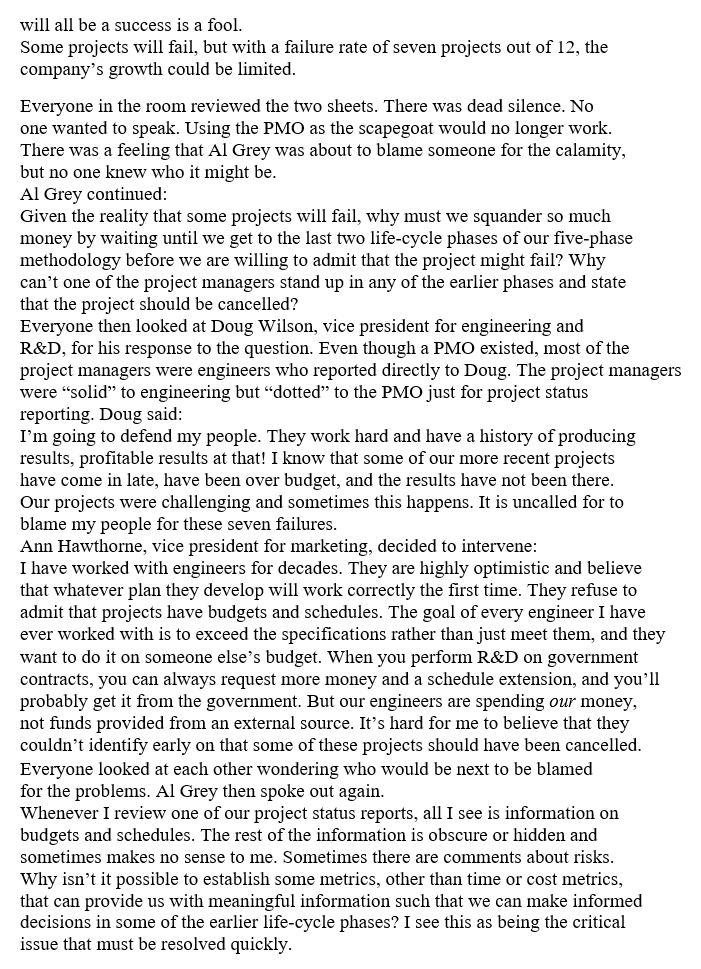

Please read the case study below and answer the following: 1. Who should be blamed for the failure of the projects in this case study? 2. Would you agree that the real cause of the failures appears to be a lack of good metrics? Should the PMO take the lead in the establishment of the metrics? WEEKLY EXECUTIVE STAFF MEETING Everybody knew that this would be a very unpleasant meeting. The selling price of the company's stock was near a five-year low. The company had just been downgraded by one of the rating agencies. Several Wall Street analysts wanted more information on what new projects the company was working on and the potential strength of the R\&D projects in the company's pipeline. And to make matters worse, the company was forced to slash the company's dividend payment to conserve cash. Unlike other companies that could produce new products quickly and deliver them to the marketplace with minimal cost, this company struggled. Historically, it was more of a follower than a leader. The company had problems when it came to creating value through innovation processes. In the past, whenever new products were created, the company was good at adding value to existing products using process reengineering, product modifications and enhancements, quality initiatives, and business process improvements. But this alone would not get the company through the current turbulent economic times. Innovation was a necessity and needed to happen quickly. The creation of customer-recognized value was needed, and the company was struggling. As Al Grey, president and chief executive officer, entered the room, everyone could see that he was not happy. The company was in trouble and nobody really had a plan for how to rectify the situation. Finger-pointing and the laying of blame elsewhere had become the norm. The company had a multitude of talented people, but their achievements were less than par. This was particularly true of the R&D Group and the Engineering Departments responsible for the development of new products. Al Grey stood up and addressed the senior staff: I believe that I have identified the root cause of our innovation problems and we should be able to come up with a solution. I'm passing out to each of you two sheets of paper. In the first sheet (see Figure I), I have identified seven R\&D projects that we considered to be total failures. You'll notice that five of the seven projects that failed consumed some of our most talented people and yet there were no new products developed from these five projects or from the other two projects. You'll also notice in which life cycle phase we made the decision to pull the plug on these projects. Several of these projects had gone through to completion before we discovered, or should I say were willing to admit, that the projects would produce no fruitful results. Over the past year, we worked on a total of 12 high-priority R&D projects where we were convinced that success would be forthcoming. Only five of these projects generated any revenue stream, and none of the five was considered a "home run" producing the desired cash flow. In the second sheet of paper (see Table I), I have shown how much money we have squandered on the seven projects that failed. We threw away millions of dollars. Several of you have pointed the finger at the project management office and tried to put the entire blame on their shoulders, claiming that the process we use for our portfolio selection of projects was at fault. While it is true that perhaps our process, like any other process, could be improved, all of us in this room still agreed with their selection recommendations. Not all projects that we recommend will be successful and any executive in this room who believes that they will all be a success is a fool. Some projects will fail, but with a failure rate of seven projects out of 12 , the company's growth could be limited. Everyone in the room reviewed the two sheets. There was dead silence. No one wanted to speak. Using the PMO as the scapegoat would no longer work. There was a feeling that Al Grey was about to blame someone for the calamity, but no one knew who it might be. Al Grey continued: Given the reality that some projects will fail, why must we squander so much money by waiting until we get to the last two life-cycle phases of our five-phase methodology before we are willing to admit that the project might fail? Why can't one of the project managers stand up in any of the earlier phases and state that the project should be cancelled? Everyone then looked at Doug Wilson, vice president for engineering and R&D, for his response to the question. Even though a PMO existed, most of the project managers were engineers who reported directly to Doug. The project managers were "solid" to engineering but "dotted" to the PMO just for project status reporting. Doug said: I'm going to defend my people. They work hard and have a history of producing results, profitable results at that! I know that some of our more recent projects have come in late, have been over budget, and the results have not been there. Our projects were challenging and sometimes this happens. It is uncalled for to blame my people for these seven failures. Ann Hawthorne, vice president for marketing, decided to intervene: I have worked with engineers for decades. They are highly optimistic and believe that whatever plan they develop will work correctly the first time. They refuse to admit that projects have budgets and schedules. The goal of every engineer I have ever worked with is to exceed the specifications rather than just meet them, and they want to do it on someone else's budget. When you perform R\&D on government contracts, you can always request more money and a schedule extension, and you'll probably get it from the government. But our engineers are spending our money, not funds provided from an external source. It's hard for me to believe that they couldn't identify early on that some of these projects should have been cancelled. Everyone looked at each other wondering who would be next to be blamed for the problems. Al Grey then spoke out again. Whenever I review one of our project status reports, all I see is information on budgets and schedules. The rest of the information is obscure or hidden and sometimes makes no sense to me. Sometimes there are comments about risks. Why isn't it possible to establish some metrics, other than time or cost metrics, that can provide us with meaningful information such that we can make informed decisions in some of the earlier life-cycle phases? I see this as being the critical issue that must be resolved quickly. FIGURE I Failure identification per life cycle phase TABLE I R\&D TERMINATION COSTS AND REASONS FOR FAILURE After a brief discussion, everyone seemed to agree that better metrics could alleviate some of the problems. But getting agreement on the identification of the problem was a lot easier than finding a solution. New issues on how to perform metrics management would now be surfacing, and most of the people in the room had limited experience with metrics management. The company had a PMO that reported to Carol Daniels, chief information officer. The PMO was created for several reasons, including the development of an enterprise project management methodology, support for the senior staff in the project portfolio selection process, and creation of executive-level dashboards that would provide information on the performance of the strategic plan. Carol then commented: Our PMO has expertise with metrics, but business-based metrics rather than project-based metrics. Our dashboards contain information on financial metrics such as profitability, market share, number of new customers, percentage of our business that is repeat business, customer satisfaction, quality survey results, and so forth. I will ask the PMO to take the lead in this, but I honestly have no clue how long it will take or the complexities with designing project-based metrics. Everyone seemed relieved and pleased that Carol Daniels would take the lead role in establishing a project-based metric system. But there were still concerns and issues that needed to be addressed, and it was certainly possible that this solution could not be achieved even after the expenditure of significant time and effort on metric management. Al Grey then stated that he wanted another meeting with the executive staff scheduled in a few days where the only item up for discussion would be the plan for developing the metrics. Everyone in the room was given the same action item in preparation for the next meeting: "Prepare a list of what metrics you feel are necessary for early-on informed project decision making and what potential problems we must address in order to accomplish this