Question: PLZ ANSWER THE QUESTIONS BELOW!! In the Target case, identify and explain two things that you would you have done differently from the CEO perspective?

PLZ ANSWER THE QUESTIONS BELOW!!

In the Target case, identify and explain two things that you would you have done differently from the CEO perspective?

What did Target do that was beneficial (identify and describe two (2) items)?

What actions of Target where detrimental or caused deterioration of this incident/situation (identify and describe two (2) items)?

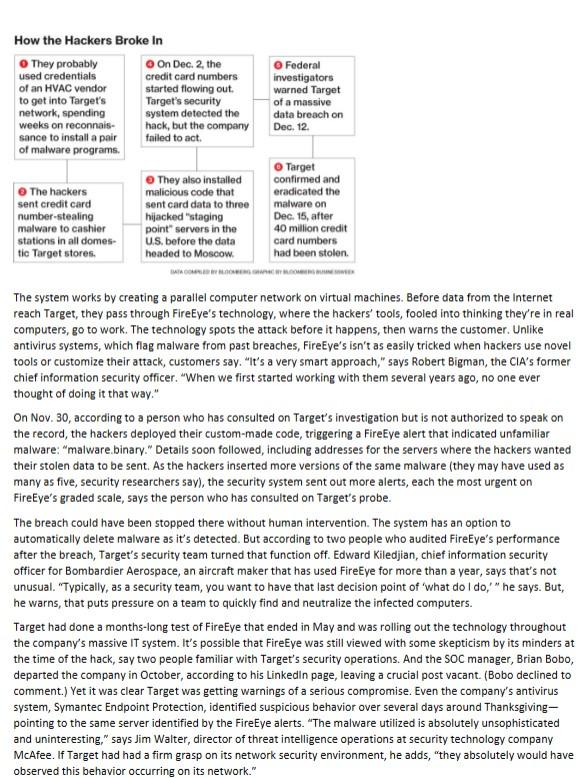

CASE STUDY 1 TARGET Missed Alarms and 40 Million Stolen Credit Card Numbers: How Target Blew it Target ignored its own alarms - and turned its customers into victims by Michael Riley The biggest retail hack in U.S. history wasn't particularly inventive, nor did it appear destined for success. In the days prior to Thanksgiving 2013, someone installed malware in Target's security and payments system designed to steal every credit card used at the company's 1,797 U.S. stores. At the critical moment-when the Christmas gifts had been scanned and bagged and the cashier asked for a swipe-the malware would step in, capture the shopper's credit card number, and store it on a Target server commandeered by the hackers. It's a measure of how common these crimes have become, and how conventional the hackers' approach in this case, that Target was prepared for such an attack. Six months earlier the company began installing a $1.6million malware detection tool made by the computer security firm FireEye, whose customers also include the CIA and the Pentagon. Target had a team of security specialists in Bangalore to monitor its computers around the clock. If Bangalore noticed anything suspicious, Target's security operations center in Minneapolis would be notified. On Saturday, Nov. 30, the hackers had set their traps and had just one thing to do before starting the attack: plan the data's escape route. As they uploaded exfiltration malware to move stolen credit card numbers-first to staging points spread around the U.S. to cover their tracks, then into their computers in Russia-FireEye spotted them. Bangalore got an alert and flagged the security team in Minneapolis. And then ... Nothing happened. For some reason, Minneapolis didn't react to the sirens. Bloomberg Businessweek spoke to more than 10 former Target employees familiar with the company's data security operation, as well as eight people with specific knowledge of the hack and its aftermath, including former employees, security researchers, and law enforcement officials. The story they tell is of an alert system, installed to protect the bond between retailer and customer that worked beautifully. But then, Target stood by as 40 million credit card numbers-and 70 million addresses, phone numbers, and other pieces of personal information-gushed out of its mainframes. When asked to respond to a list of specific questions about the incident and the company's lack of an immediate response to it, Target Chairman, President, and Chief Executive Officer Gregg Steinhafel issued an e-mailed statement: "Target was certified as meeting the standard for the payment card industry (PCl) in September 2013. Nonetheless, we suffered a data breach. As a result, we are conducting an end-to-end review of our people, processes and technology to understand our opportunities to improve data security and are committed to learning from this experience. While we are still in the midst of an ongoing investigation, we have already taken significant steps, including beginning the overhaul of our information security structure and the acceleration of our transition to chip-enabled cards. However, as the investigation is not complete, we don't believe it's constructive to engage in speculation without the benefit of the final analysis." More than 90 lawsuits have been filed against Target by customers and banks for negligence and compensatory damages. That's on top of other costs, which analysts estimate could run into the billions. Target spent $61 million through Feb. 1 responding to the breach, according to its fourth-quarter report to investors. It set up a customer response operation, and in an effort to regain lost trust, Steinhafel promised that consumers won't have to pay any fraudulent charges stemming from the breach. Target's profit for the holiday shopping period fell 46 percent from the same quarter the year before; the number of transactions suffered its biggest decline since the retailer began reporting the statistic in 2008 . In testimony before Congress, Target has said that it was only after the U.S. Department of Justice notified the retailer about the breach in mid-December that company investigators went back to figure out what happened. What it hasn't publicly revealed: Poring over computer logs, Target found FireEye's alerts from Nov. 30 and more from Dec. 2, when hackers installed yet another version of the malware. Not only should those alarms have been impossible to miss, they went off early enough that the hackers hadn't begun transmitting the stolen card data out of Target's network. Had the company's security team responded when it was supposed to, the theft that has since engulfed Target, touched as many as one in three American consumers, and led to an international manhunt for the hackers never would have happened at all. The heart of Target's antihacking operation is cloistered in a corner room on the sixth floor of a building in downtown Minneapolis. There are no internal-facing windows, just a locked door. Visitors ring a bell, then wait for a visual scan before being buzzed in. If you've seen one security operations center, or SOC, you've essentially seen them all. Inside, analysts sit in front of rows of screens that monitor Target's billion-dollar IT infrastructure. Government agencies often build their own SOCs, as do big banks, defense contractors, tech companies, wireless carriers, and other corporations with centralized stockpiles of high-value information. Retailers, however, tend not to. Most still focus on their primary mission, selling stuff-in part because their sprawling networks of stores and e-tailing entry points are difficult to lock down against incursions. A three-year study by Verizon Enterprise Solutions found that companies discover breaches through their own monitoring in only 31 percent of cases. For retailers, it's 5 percent. They're the wildebeests of the digital savannah. Target was striving to be different. Company officials say its information security staff now numbers more than 300 people-a tenfold increase since 2006 , says one of the chain's former information security managers. Less than a year before the Thanksgiving attack, Target brought in FireEye, a security software company in Milpitas, Calif., that was initially funded by the CIA and is used by intelligence agencies around the world. The system works by creating a parallel computer network on virtual machines. Before data from the internet reach Target, they pass through FireEye's technology, where the hackers' tools, fooled into thinking they're in real computers, go to work. The technology spots the attack before it happens, then warns the customer. Unlike antivirus systems, which flag malware from past breaches, FireEye's isn't as easily tricked when hackers use novel tools or customize their attack, customers say. "It's a very smart approach," says Robert Bigman, the ClA's former chief information security officer. "When we first started working with them several years ago, no one ever thought of doing it that way." On Nov. 30, according to a person who has consulted on Target's investigation but is not authorized to speak on the record, the hackers deployed their custom-made code, triggering a FireEye alert that indicated unfamiliar malware: "malware.binary." Details soon followed, including addresses for the servers where the hackers wanted their stolen data to be sent. As the hackers inserted more versions of the same malware (they may have used as many as five, security researchers say), the security system sent out more alerts, each the most urgent on FireEye's graded scale, says the person who has consulted on Target's probe. The breach could have been stopped there without human intervention. The system has an option to automatically delete malware as it's detected. But according to two people who audited FireEye's performance after the breach, Target's security team turned that function off. Edward Kiledjian, chief information security officer for Bombardier Aerospace, an aircraft maker that has used FireEye for more than a year, says that's not unusual. "Typically, as a security team, you want to have that last decision point of 'what do I do,'" he says. But, he warns, that puts pressure on a team to quickly find and neutralize the infected computers. Target had done a months-long test of FireEye that ended in May and was rolling out the technology throughout the company's massive IT system. It's possible that FireEye was still viewed with some skepticism by its minders at the time of the hack, say two people familiar with Target's security operations. And the SOC manager, Brian Bobo, departed the company in October, according to his Linkedln page, leaving a crucial post vacant. (Bobo declined to comment.) Yet it was clear Target was getting warnings of a serious compromise. Even the company's antivirus system, Symantec Endpoint Protection, identified suspicious behavior over several days around Thanksgivingpointing to the same server identified by the FireEye alerts. "The malware utilized is absolutely unsophisticated and uninteresting," says Jim Walter, director of threat intelligence operations at security technology company McAfee. If Target had had a firm grasp on its network security environment, he adds, "they absolutely would have Target's security blunders don't end there. Its spokeswoman, Molly Snyder, says the intruders had gained access to the system by using stolen credentials from a third-party vendor. Brian Krebs, a security blogger whose site krebsonsecurity.com first broke the news of the Target hack, has reported that the vendor was a refrigeration and heating company near Pittsburgh called Fazio Mechanical Services. A statement on Fazio's website says its IT systems and security measures are in compliance with industry practices, and its data connection to Target was purely for billing, contract submission, and project management. Target's system, like any standard corporate network, is segmented so that the most sensitive parts - including customer payments and personal data-are walled off from other parts of the network and, especially, the open internet. Target's walls obviously had holes. The hackers' malware disguised itself with the name Bladelogic, probably to mimic a component in a data center management product, according to a report by Dell SecureWorks. (SecureWorks is one of many cybersecurity firms that got their hands on the Target malware, which was made public on various websites used by researchers to help other companies fend off similar attacks.) In other words, the hackers cloaked their bad code with the name of legitimate software used by companies to protect cardholder and payment data. Once their malware was successfully in place on Nov. 30-the data didn't actually start moving out of Target's network until Dec. 2-the hackers had almost two weeks to pillage credit card numbers unmolested. According to SecureWorks, the malware was designed to send data automatically to three different U.S. staging points, working only between the hours of 10a.m. and 6p.m. Central Standard Time. That was presumably to make sure the outbound data would be submerged in regular working-hours traffic. From there the card information went to Moscow. Seculert, an Israeli security firm, was able to analyze the hackers' activity on one of the U.S.-based staging points, which showed them eventually taking 11 gigabytes of data stored there to a Moscow-based hosting service called vpsville.ru. Alexander Kiva, spokesman for vpsville.ru, says the company has too many clients to monitor them effectively, and that it hadn't been contacted by U.S. investigators as of February. If Target's security team had followed up on the earliest FireEye alerts, it could have been right behind the hackers on their escape path. The malware had user names and passwords for the thieves' staging servers embedded in the code, according to Jaime Blasco, a researcher for the security firm AlienVault Labs. Target security could have signed in to the servers themselves-located in Ashburn, Va., Provo, Utah, and Los Angeles and seen the stolen data sitting there waiting for the hackers' daily pickup. But by the time company investigators figured that out, the data were long gone. Federal law enforcement officials contacted Target about the breach on Dec. 12, according to congressional testimony. CEO Steinhafel has said that it took his company three days to confirm it. The authorities had more than just reports of fraudulent charges to go on, however: They had obtained the actual stolen data, which the hackers had carelessly left on their dump servers, according to a person familiar with the federal investigation. Target first publicly confirmed the breach in a press release at 6 a.m. on Dec. 19. Kelly Warpechowski, a 23-yearold IT recruiter in Milwaukee, already knew something was wrong. Her bank notified her that someone in Russia had spent $900 at "an oil company" using her card. Target had been Warpechowski's go-to store, but she says she's visited only twice since. That night, Jamie Doyle, who's in the Navy and lives in Chesapeake, Va., got a fraud alert from the Navy Federal Credit Union while he was on overnight shipboard duty. His wife, Tracy, a school speech pathologist, checked the next morning and found their debit card had been drained, with more than $600 in pending charges. "We were literally going in to buy our Christmas dinner, and we had no money," she says. Jamie, who almost never shopped at Target, had used his debit card to grab $5 worth of groceries from a Chesapeake store on Black Friday. The card number was then used by thieves at an Ellicott City (Md.) Target store, Tracy says. She blames the retailer for the breach and for not checking more closely when the fraudulent user rang up the charges. Why didn't the cashier ask for ID to verify the cardholder, she wonders. The bank credited the Doyles' account in two days, Tracy says. She no longer shops at Target. The anger has spilled into Congress, where company officials, including Chief Financial Officer John Mulligan, were called to testify in February. The House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, which this week received from Target documents related to what executives knew and when they knew it, will now seek additional material related to Bloomberg Businessweek's reporting, said Frederick Hill, a spokesman for U.S. Representative Darrell Issa, the panel's chairman. "The Oversight Committee has asked Target when it will be producing documents related to the November 30 incident," Hill said. Major banks and store chains are pointing fingers at each other over years of delay in adopting a more secure technology that uses cards with embedded chips. Such cards, now common throughout Europe, are harder to counterfeit than those with magnetic strips. Target executives-Chief Information Officer Beth Jacob resigned on March 5-promise that their company will help lead that transition; they announced in February that they'll spend $100 million for registers and other technology that read the new cards. Its stock is trading near $61, almost unchanged since the day it disclosed the hack. FireEye shares have more than doubled, to around $80. Sometime in early March someone broke into Rescator.so and stole the logins, passwords, and payment information of carders, then posted the data online. Krebs says it's unclear who was behind the hack, but it appears to be someone who wanted to shut the operation down, possibly vigilantes or competitors

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts