Question: Question! Indalex: Discuss the following operations categories for this site in relation to company and operations strategy: capacity, facilities, technology, vertical integration, sourcing, work force,

Question!

Indalex: Discuss the following operations categories for this site in relation to company and operations strategy: capacity, facilities, technology, vertical integration, sourcing, work

force, quality, production planning and control, and organization. Do the decisions made

in these areas fit the corporate strategy? In what ways, or why not?

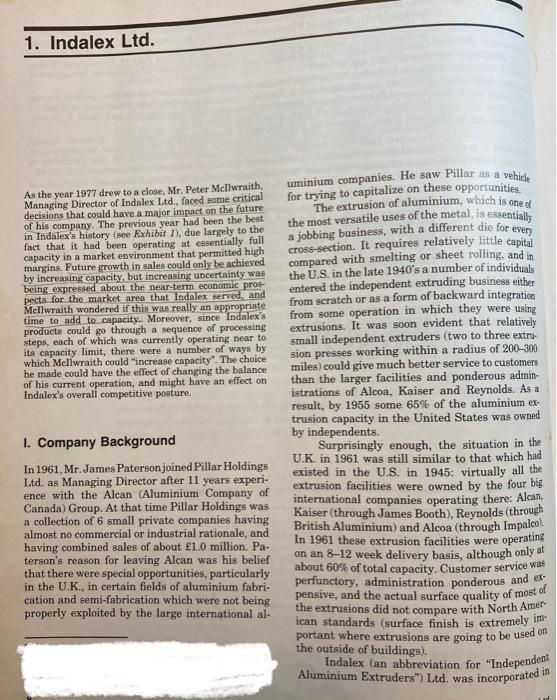

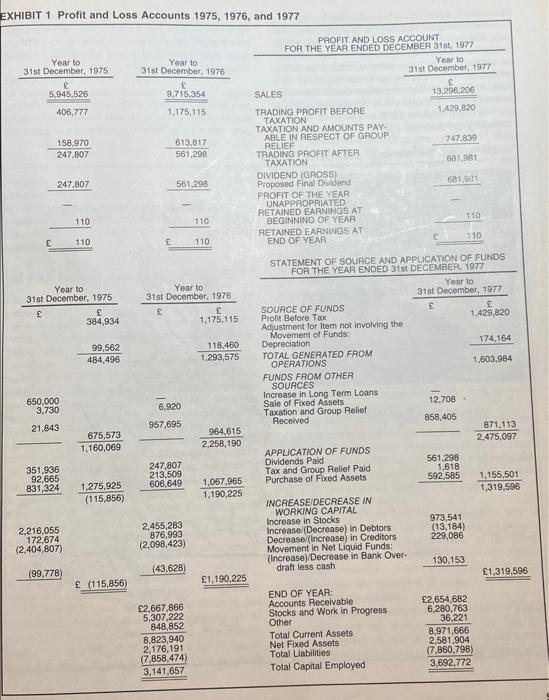

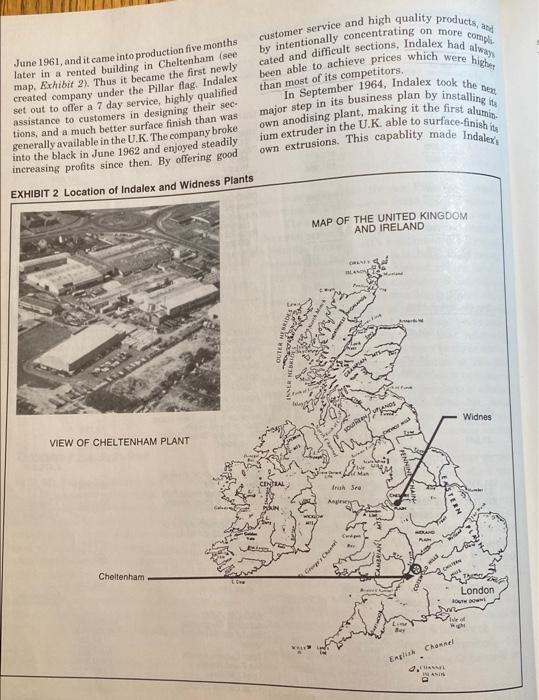

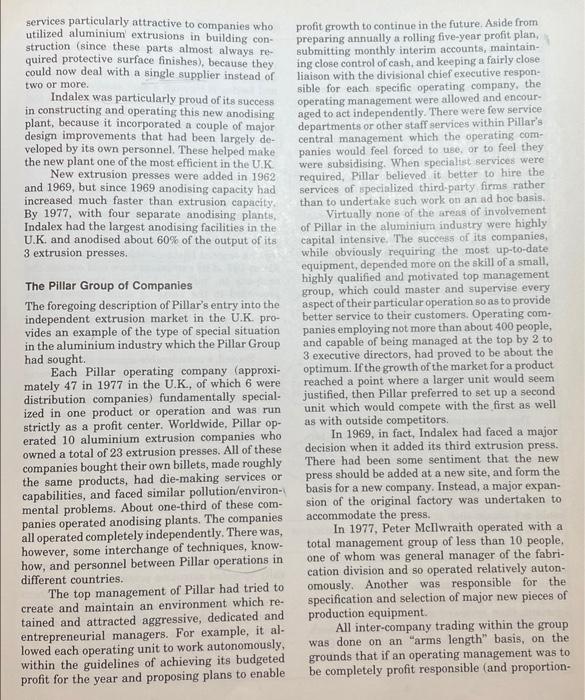

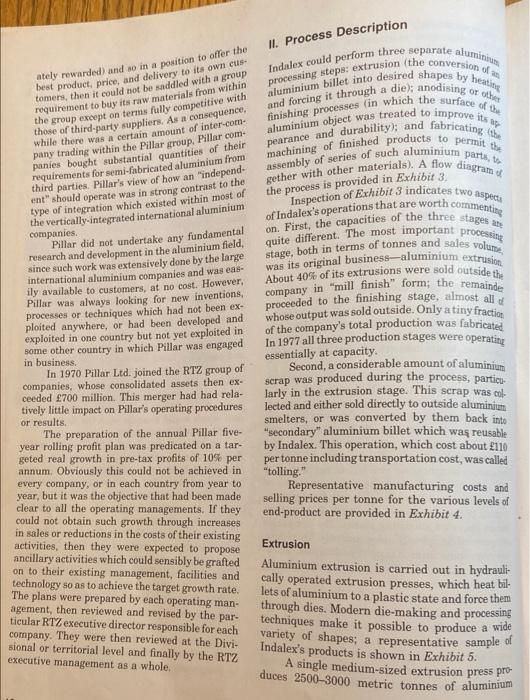

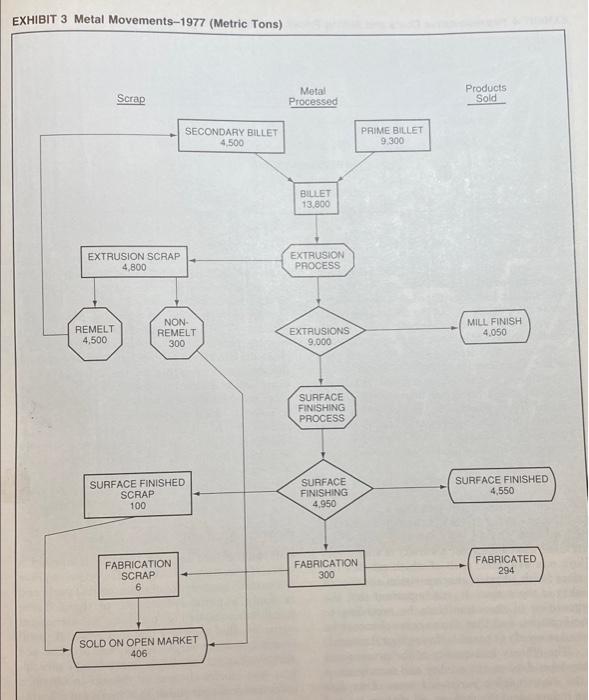

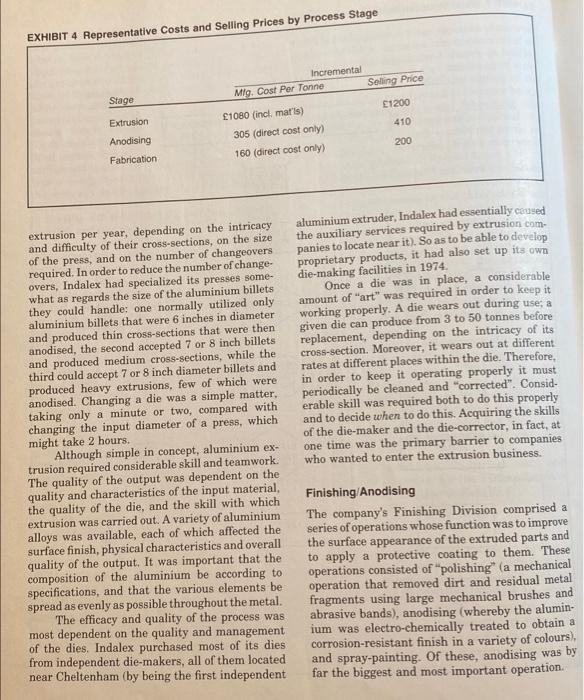

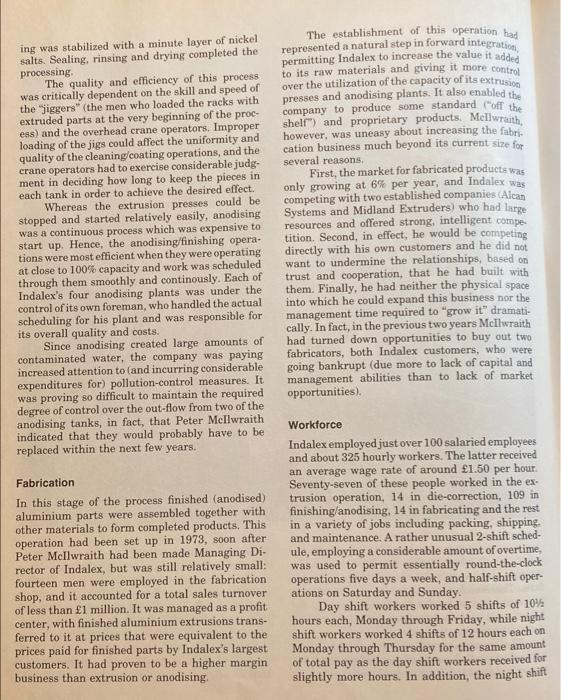

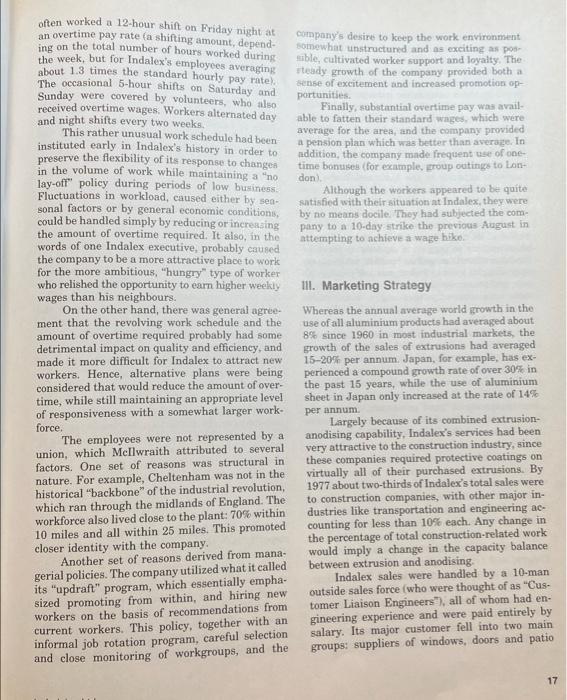

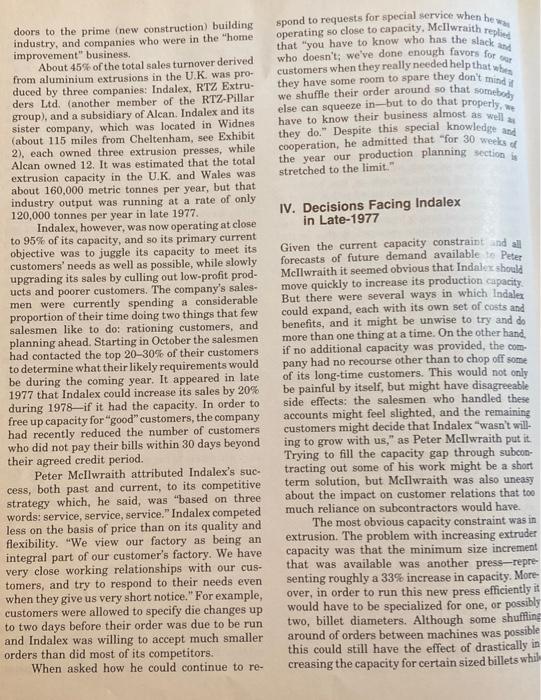

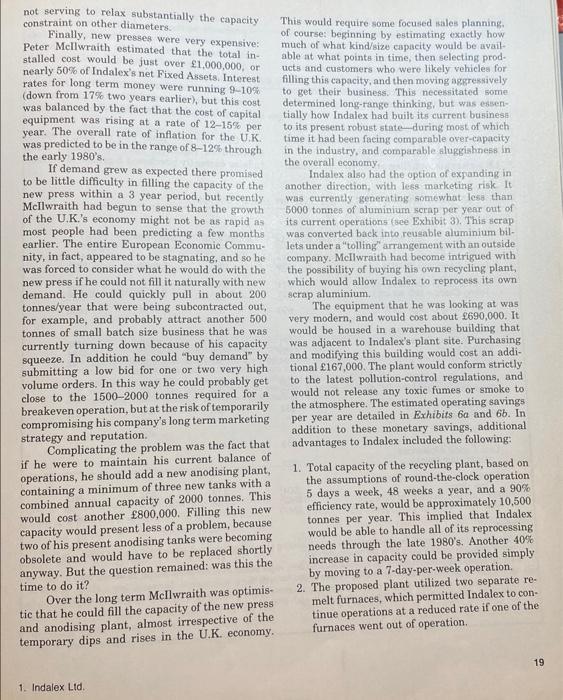

1. Indalex Ltd. As the year 1977 drew to a close, Mr. Peter Mcllwraith, Managing Director of Indalex Ltd., faced some critical decisions that could have a major impact on the future of his company. The previous year had been the best in Indalex's history (see Exhibit 1), due largely to the fact that it had been operating at essentially full capacity in a market environment that permitted high margins. Future growth in sales could only be achieved by increasing capacity, but increasing uncertainty was being expressed about the near-term economic pros- pects for the market area that Indalex served, and Mellwraith wondered if this was really an appropriate time to add to capacity. Moreover, since Indalex's products could go through a sequence of processing steps, each of which was currently operating near to its capacity limit, there were a number of ways by which Mellwraith could "increase capacity". The choice he made could have the effect of changing the balance of his current operation, and might have an effect on Indalex's overall competitive posture. I. Company Background In 1961, Mr. James Paterson joined Pillar Holdings Ltd. as Managing Director after 11 years experi- ence with the Alcan (Aluminium Company of Canada) Group. At that time Pillar Holdings was a collection of 6 small private companies having almost no commercial or industrial rationale, and having combined sales of about 1.0 million. Pa- terson's reason for leaving Alcan was his belief that there were special opportunities, particularly in the U.K., in certain fields of aluminium fabri- cation and semi-fabrication which were not being properly exploited by the large international al- uminium companies. He saw Pillar as a vehicle for trying to capitalize on these opportunities. The extrusion of aluminium, which is one of the most versatile uses of the metal, is essentially a jobbing business, with a different die for every cross-section. It requires relatively little capital compared with smelting or sheet rolling, and in the U.S. in the late 1940's a number of individuals entered the independent extruding business either. from scratch or as a form of backward integration from some operation in which they were using extrusions. It was soon evident that relatively small independent extruders (two to three extru- sion presses working within a radius of 200-300 miles) could give much better service to customers. than the larger facilities and ponderous admin- istrations of Alcoa, Kaiser and Reynolds. As a result, by 1955 some 65% of the aluminium ex- trusion capacity in the United States was owned by independents. Surprisingly enough, the situation in the U.K. in 1961 was still similar to that which had existed in the U.S. in 1945: virtually all the extrusion facilities were owned by the four big international companies operating there: Alcan, Kaiser (through James Booth), Reynolds (through British Aluminium) and Alcoa (through Impalco. In 1961 these extrusion facilities were operating on an 8-12 week delivery basis, although only at about 60% of total capacity. Customer service was perfunctory, administration ponderous and ex- pensive, and the actual surface quality of most of the extrusions did not compare with North Amer ican standards (surface finish is extremely im- portant where extrusions are going to be used on the outside of buildings). Aluminium Extruders") Ltd. was Indalex (an abbreviation for "Independent incorporated in EXHIBIT 1 Profit and Loss Accounts 1975, 1976, and 1977 Year to 31st December, 1975 Year to 31st December, 1976 E 5,945,526 9,715,354 406,777 1,175,115 158,970 613,817 247,807 561,298 247,807 561,298 110 110 110 110 Year to 31st December, 1975 Year to 31st December, 1976 384,934 1,175,115 99,562 118,460 484,496 1,293,575 650,000 3,730 21,843 675,573 964,615 1,160,069 2,258,190 351,936 92,665 1,067,965 831,324 1,275,925 (115,856) 1,190,225 2,216,055 172,674 (2,404,807) (99,778) 1,190,225 (115,856) 6,920 957,695 247,807 213,509 606,649 2,455,283 876,993 (2,098,423) (43,628) 2,667,866 5,307,222 848,852 8,823,940 2,176,191 (7.858,474) 3,141,657 PROFIT AND LOSS ACCOUNT FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31st, 1977 Year to 31st December, 1977 SALES 13,296,206 1,429,820 TRADING PROFIT BEFORE TAXATION TAXATION AND AMOUNTS PAY- ABLE IN RESPECT OF GROUP 747,839 RELIEF TRADING PROFIT AFTER TAXATION 681,981 681,901 DIVIDEND (GROSS) Proposed Final Dividend PROFIT OF THE YEAR UNAPPROPRIATED RETAINED EARNINGS AT BEGINNING OF YEAR RETAINED EARNINGS AT END OF YEAR 110 110 STATEMENT OF SOURCE AND APPLICATION OF FUNDS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31st DECEMBER, 1977 Year to 31st December, 1977 SOURCE OF FUNDS Profit Before Tax 1,429,820 Adjustment for Item not involving the Movement of Funds: Depreciation 174,164 TOTAL GENERATED FROM OPERATIONS 1,603,984 FUNDS FROM OTHER SOURCES Increase in Long Term Loans Sale of Fixed Assets Taxation and Group Relief Received 871,113 2,475,097 APPLICATION OF FUNDS Dividends Paid Tax and Group Relief Paid Purchase of Fixed Assets 1,155,501 1,319,596 INCREASE/DECREASE IN WORKING CAPITAL Increase in Stocks Increase (Decrease) in Debtors Decrease/(Increase) in Creditors Movement in Net Liquid Funds: (Increase)/Decrease in Bank Over- draft less cash 1,319,596 END OF YEAR: Accounts Receivable Stocks and Work in Progress Other Total Current Assets. Net Fixed Assets Total Liabilities Total Capital Employed 12,708 858,405 561,298 1,618 592,585 973,541 (13,184) 229,086 130,153 2,654,682 6,280,763 36,221 8,971,666 2,581,904 (7.860,798) 3,692,772 June 1961, and it came into production five months later in a rented building in Cheltenham (see map, Exhibit 2). Thus it became the first newly created company under the Pillar flag. Indalex set out to offer a 7 day service, highly qualified assistance to customers in designing their sec- tions, and a much better surface finish than was generally available in the U.K. The company broke into the black in June 1962 and enjoyed steadily increasing profits since then. By offering good EXHIBIT 2 Location of Indalex and Widness Plants AN VIEW OF CHELTENHAM PLANT Cheltenham. than most of its competitors. customer service and high quality products, and cated and difficult sections, Indalex had always by intentionally concentrating on more compli been able to achieve prices which were higher In September 1964, Indalex took the nex major step in its business plan by installing its own anodising plant, making it the first alumin ium extruder in the U.K. able to surface-finish ta own extrusions. This capablity made Indalex MAP OF THE UNITED KINGDOM AND IRELAND BLAND OUTER but Thi (Man www Irish Sea Angin (wg Gronge's Channel O Widnes yefat London OUTDOWN English Channel 2. TH INANS Isle of Wigh services particularly attractive to companies who utilized aluminium extrusions in building con- struction (since these parts almost always re- quired protective surface finishes), because they could now deal with a single supplier instead of two or more. Indalex was particularly proud of its success in constructing and operating this new anodising plant, because it incorporated a couple of major design improvements that had been largely de- veloped by its own personnel. These helped make the new plant one of the most efficient in the U.K. New extrusion presses were added in 1962 and 1969, but since 1969 anodising capacity had increased much faster than extrusion capacity. By 1977, with four separate anodising plants, Indalex had the largest anodising facilities in the U.K. and anodised about 60% of the output of its 3 extrusion presses. The Pillar Group of Companies The foregoing description of Pillar's entry into the independent extrusion market in the U.K. pro- vides an example of the type of special situation in the aluminium industry which the Pillar Group had sought. Each Pillar operating company (approxi- mately 47 in 1977 in the U.K., of which 6 were distribution companies) fundamentally special- ized in one product or operation and was run strictly as a profit center. Worldwide, Pillar op- erated 10 aluminium extrusion companies who owned a total of 23 extrusion presses. All of these companies bought their own billets, made roughly the same products, had die-making services or capabilities, and faced similar pollution/environ- mental problems. About one-third of these com- panies operated anodising plants. The companies i all operated completely independently. There was, however, some interchange of techniques, know- how, and personnel between Pillar operations in different countries. The top management of Pillar had tried to: create and maintain an environment which re- tained and attracted aggressive, dedicated and entrepreneurial managers. For example, it al- lowed each operating unit to work autonomously, within the guidelines of achieving its budgeted. profit for the year and proposing plans to enable profit growth to continue in the future. Aside from preparing annually a rolling five-year profit plan, submitting monthly interim accounts, maintain- ing close control of cash, and keeping a fairly close liaison with the divisional chief executive respon- sible for each specific operating company, the operating management were allowed and encour- aged to act independently. There were few service departments or other staff services within Pillar's central management which the operating com- panies would feel forced to use, or to feel they were subsidising. When specialist services were required, Pillar believed it better to hire the services of specialized third-party firms rather than to undertake such work on an ad hoc basis.. Virtually none of the areas of involvement of Pillar in the aluminium industry were highly capital intensive. The success of its companies, while obviously requiring the most up-to-date equipment, depended more on the skill of a small, highly qualified and motivated top management group, which could master and supervise every aspect of their particular operation so as to provide better service to their customers. Operating com- panies employing not more than about 400 people, and capable of being managed at the top by 2 to 3 executive directors, had proved to be about the optimum. If the growth of the market for a product reached a point where a larger unit would seem justified, then Pillar preferred to set up a second unit which would compete with the first as well as with outside competitors. In 1969, in fact, Indalex had faced a major decision when it added its third extrusion press. There had been some sentiment that the new press should be added at a new site, and form the basis for a new company. Instead, a major expan- sion of the original factory was undertaken to accommodate the press. In 1977, Peter Mellwraith operated with a total management group of less than 10 people, one of whom was general manager of the fabri- cation division and so operated relatively auton- omously. Another was responsible for the specification and selection of major new pieces of production equipment. All inter-company trading within the group was done on an "arms length" basis, on the grounds that if an operating management was to be completely profit responsible (and proportion- II. Process Description Indalex could perform three separate aluminiu processing steps: extrusion (the conversion of an aluminium billet into desired shapes by heating and forcing it through a die); anodising or other finishing processes (in which the surface of the aluminium object was treated to improve its ap pearance and durability); and fabricating the machining of finished products to permit the assembly of series of such aluminium parts, t gether with other materials). A flow diagram of the process is provided in Exhibit 3. Inspection of Exhibit 3 indicates two aspects of Indalex's operations that are worth commenting on. First, the capacities of the three stages are quite different. The most important processing stage, both in terms of tonnes and sales volume, was its original business-aluminium extrusion About 40% of its extrusions were sold outside the proceeded to the finishing stage, almost all d company in "mill finish" form; the remainder whose output was sold outside. Only a tiny fraction of the company's total production was fabricated In 1977 all three production stages were operating essentially at capacity. Second, a considerable amount of aluminium scrap was produced during the process, particu larly in the extrusion stage. This scrap was col- lected and either sold directly to outside aluminium smelters, or was converted by them back into "secondary" aluminium billet which was reusable by Indalex. This operation, which cost about 110 per tonne including transportation cost, was called "tolling." Representative manufacturing costs and selling prices per tonne for the various levels of end-product are provided in Exhibit 4. Extrusion Aluminium extrusion is carried out in hydrauli cally operated extrusion presses, which heat bil- lets of aluminium to a plastic state and force them through dies. Modern die-making and processing techniques make it possible to produce a wide variety of shapes; a representative sample of Indalex's products is shown in Exhibit 5. A single medium-sized extrusion press pro duces 2500-3000 metric tonnes of aluminium ately rewarded) and so in a position to offer the best product, price, and delivery to its own cus- tomers, then it could not be saddled with a group requirement to buy its raw materials from within the group except on terms fully competitive with those of third-party suppliers. As a consequence, while there was a certain amount of inter-com- pany trading within the Pillar group, Pillar com- panies bought substantial quantities of their requirements for semi-fabricated aluminium from third parties. Pillar's view of how an "independ- ent" should operate was in strong contrast to the type of integration which existed within most of the vertically-integrated international aluminium companies. Pillar did not undertake any fundamental research and development in the aluminium field, since such work was extensively done by the large international aluminium companies and was eas- ily available to customers, at no cost. However, Pillar was always looking for new inventions, processes or techniques which had not been ex- ploited anywhere, or had been developed and exploited in one country but not yet exploited in some other country in which Pillar was engaged in business. In 1970 Pillar Ltd. joined the RTZ group of companies, whose consolidated assets then ex- ceeded 700 million. This merger had had rela- tively little impact on Pillar's operating procedures or results.. The preparation of the annual Pillar five- year rolling profit plan was predicated on a tar- geted real growth in pre-tax profits of 10% per annum. Obviously this could not be achieved in every company, or in each country from year to year, but it was the objective that had been made clear to all the operating managements. If they could not obtain such growth through increases in sales or reductions in the costs of their existing activities, then they were expected to propose ancillary activities which could sensibly be grafted on to their existing management, facilities and technology so as to achieve the target growth rate. The plans were prepared by each operating man- agement, then reviewed and revised by the par- ticular RTZ executive director responsible for each company. They were then reviewed at the Divi- sional or territorial level and finally by the RTZ executive management as a whole. EXHIBIT 3 Metal Movements-1977 (Metric Tons) Scrap SECONDARY BILLET 4,500 EXTRUSION SCRAP 4,800 NON- REMELT 300 SURFACE FINISHED SCRAP 100 FABRICATION SCRAP 6 SOLD ON OPEN MARKET 406 REMELT 4,500 Metal Processed BILLET 13,800 EXTRUSION PROCESS EXTRUSIONS 9,000 SURFACE FINISHING PROCESS SURFACE FINISHING 4,950 FABRICATION 300 PRIME BILLET 9.300 Products Sold MILL FINISH 4,050 SURFACE FINISHED 4,550 FABRICATED 294 EXHIBIT 4 Representative Costs and Selling Prices by Process Stage Incremental Stage Mig. Cost Per Tonne Extrusion Anodising 305 (direct cost only) 160 (direct cost only) Fabrication extrusion per year, depending on the intricacy and difficulty of their cross-sections, on the size of the press, and on the number of changeovers required. In order to reduce the number of change- overs, Indalex had specialized its presses some- what as regards the size of the aluminium billets they could handle: one normally utilized only aluminium billets that were 6 inches in diameter and produced thin cross-sections that were then anodised, the second accepted 7 or 8 inch billets and produced medium cross-sections, while the third could accept 7 or 8 inch diameter billets and produced heavy extrusions, few of which were anodised. Changing a die was a simple matter, taking only a minute or two, compared with changing the input diameter of a press, which might take 2 hours. Although simple in concept, aluminium ex- trusion required considerable skill and teamwork. The quality of the output was dependent on the quality and characteristics of the input material, the quality of the die, and the skill with which extrusion was carried out. A variety of aluminium. alloys was available, each of which affected the surface finish, physical characteristics and overall quality of the output. It was important that the composition of the aluminium be according to specifications, and that the various elements be spread as evenly as possible throughout the metal. The efficacy and quality of the process was most dependent on the quality and management of the dies. Indalex purchased most of its dies from independent die-makers, all of them located. near Cheltenham (by being the first independent Selling Price 1200 410 200 aluminium extruder, Indalex had essentially caused the auxiliary services required by extrusion com- panies to locate near it). So as to be able to develop proprietary products, it had also set up its own die-making facilities in 1974. Once a die was in place, a considerable amount of "art" was required in order to keep it working properly. A die wears out during use; a given die can produce from 3 to 50 tonnes before replacement, depending on the intricacy of its cross-section. Moreover, it wears out at different rates at different places within the die. Therefore, in order to keep it operating properly it must periodically be cleaned and "corrected". Consid- erable skill was required both to do this properly and to decide when to do this. Acquiring the skills of the die-maker and the die-corrector, in fact, at one time was the primary barrier to companies who wanted to enter the extrusion business. Finishing/Anodising The company's Finishing Division comprised a series of operations whose function was to improve the surface appearance of the extruded parts and to apply a protective coating to them. These operations consisted of "polishing" (a mechanical operation that removed dirt and residual metal fragments using large mechanical brushes and abrasive bands), anodising (whereby the alumin- ium was electro-chemically treated to obtain a corrosion-resistant finish in a variety of colours), and spray-painting. Of these, anodising was by far the biggest and most important operation. 1080 (incl. matls) EXHIBIT 5 Examples of Products I First the parts were hand-loaded onto racks, called "jigs," which facilitated their movement through the sequence of electrochemical opera- tions. These took place in a row of long narrow tanks which contained a variety of chemical so- lutions, and in some of which circulated strong electrical currents. The jigs containing the extrusions were moved by hand-controlled overhead cranes from one tank. to the next, and left for standard periods of time.. } H L First, the extrusions were cleaned, then rinsed, and then etched (etching created the actual final surface appearance of the finished piece). The surfaces were then treated in the anodising tanks to form a tough protective coating of a prespecified thickness of aluminium oxide on them which resisted corrosion and discoloration. After a rinse, the parts were ready for the application, if re- quired, of one of the five color additions that Indalex offered. Next, the aluminium oxide coat- ing was stabilized with a minute layer of nickel. salts. Sealing, rinsing and drying completed the processing. The quality and efficiency of this process was critically dependent on the skill and speed of the "jiggers" (the men who loaded the racks with extruded parts at the very beginning of the proc- ess) and the overhead crane operators. Improper loading of the jigs could affect the uniformity and quality of the cleaning/coating operations, and the crane operators had to exercise considerable judg- ment in deciding how long to keep the pieces in each tank in order to achieve the desired effect. Whereas the extrusion presses could be stopped and started relatively easily, anodising was a continuous process which was expensive to start up. Hence, the anodising/finishing opera- tions were most efficient when they were operating at close to 100% capacity and work was scheduled through them smoothly and continously. Each of Indalex's four anodising plants was under the control of its own foreman, who handled the actual scheduling for his plant and was responsible for its overall quality and costs. Since anodising created large amounts of contaminated water, the company was paying increased attention to (and incurring considerable expenditures for) pollution-control measures. It was proving so difficult to maintain the required degree of control over the out-flow from two of the anodising tanks, in fact, that Peter Mcllwraith indicated that they would probably have to be replaced within the next few years. Fabrication In this stage of the process finished (anodised) aluminium parts were assembled together with other materials to form completed products. This operation had been set up in 1973, soon after Peter Mcllwraith had been made Managing Di- rector of Indalex, but was still relatively small: fourteen men were employed in the fabrication shop, and it accounted for a total sales turnover of less than 1 million. It was managed as a profit center, with finished aluminium extrusions trans- ferred to it at prices that were equivalent to the prices paid for finished parts by Indalex's largest customers. It had proven to be a higher margin business than extrusion or anodising. The establishment of this operation had represented a natural step in forward integration, permitting Indalex to increase the value it added to its raw materials and giving it more control over the utilization of the capacity of its extrusion presses and anodising plants. It also enabled the company to produce some standard ("off the shelf") and proprietary products. Mellwraith, however, was uneasy about increasing the fabri cation business much beyond its current size for several reasons. First, the market for fabricated products was only growing at 6% per year, and Indalex was competing with two established companies (Alcan Systems and Midland Extruders) who had large resources and offered strong, intelligent compe tition. Second, in effect, he would be competing directly with his own customers and he did not want to undermine the relationships, based on trust and cooperation, that he had built with them. Finally, he had neither the physical space into which he could expand this business nor the management time required to "grow it" dramati- cally. In fact, in the previous two years Mcllwraith had turned down opportunities to buy out two- fabricators, both Indalex customers, who were going bankrupt (due more to lack of capital and management abilities than to lack of market opportunities). Workforce Indalex employed just over 100 salaried employees and about 325 hourly workers. The latter received an average wage rate of around 1.50 per hour. Seventy-seven of these people worked in the ex- trusion operation, 14 in die-correction, 109 in finishing/anodising, 14 in fabricating and the rest in a variety of jobs including packing, shipping. and maintenance. A rather unusual 2-shift sched- ule, employing a considerable amount of overtime, was used to permit essentially round-the-clock operations five days a week, and half-shift oper- ations on Saturday and Sunday. Day shift workers worked 5 shifts of 10% hours each, Monday through Friday, while night shift workers worked 4 shifts of 12 hours each on Monday through Thursday for the same amount of total pay as the day shift workers received for slightly more hours. In addition, the night shift often worked a 12-hour shift on Friday night at an overtime pay rate (a shifting amount, depend- ing on the total number of hours worked during the week, but for Indalex's employees averaging about 1.3 times the standard hourly pay rate). The occasional 5-hour shifts on Saturday and Sunday were covered by volunteers, who also received overtime wages. Workers alternated day and night shifts every two weeks. This rather unusual work schedule had been instituted early in Indalex's history in order to preserve the flexibility of its response to changes in the volume of work while maintaining a "no lay-off" policy during periods of low business. Fluctuations in workload, caused either by sea- sonal factors or by general economic conditions, could be handled simply by reducing or increasing the amount of overtime required. It also, in the words of one Indalex executive, probably caused the company to be a more attractive place to work for the more ambitious, "hungry" type of worker who relished the opportunity to earn higher weekly wages than his neighbours. On the other hand, there was general agree- ment that the revolving work schedule and the amount of overtime required probably had some detrimental impact on quality and efficiency, and made it more difficult for Indalex to attract new i workers. Hence, alternative plans were being considered that would reduce the amount of over- time, while still maintaining an appropriate level of responsiveness with a somewhat larger work- force. The employees were not represented by a union, which Mellwraith attributed to several factors. One set of reasons was structural in nature. For example, Cheltenham was not in the historical "backbone" of the industrial revolution, which ran through the midlands of England. The workforce also lived close to the plant: 70% within 10 miles and all within 25 miles. This promoted closer identity with the company. Another set of reasons derived from mana- gerial policies. The company utilized what it called its "updraft" program, which essentially empha- sized promoting from within, and hiring new workers on the basis of recommendations from current workers. This policy, together with an informal job rotation program, careful selection and close monitoring of workgroups, and the company's desire to keep the work environment somewhat unstructured and as exciting as pos sible, cultivated worker support and loyalty. The steady growth of the company provided both a sense of excitement and increased promotion op- portunities. Finally, substantial overtime pay was avail- able to fatten their standard wages, which were average for the area, and the company provided a pension plan which was better than average. In addition, the company made frequent use of one- time bonuses (for example, group outings to Lon- don). Although the workers appeared to be quite satisfied with their situation at Indalex, they were by no means docile. They had subjected the com- pany to a 10-day strike the previous August in attempting to achieve a wage hike. III. Marketing Strategy Whereas the annual average world growth in the use of all aluminium products had averaged about 8% since 1960 in most industrial markets, the growth of the sales of extrusions had averaged 15-20% per annum. Japan, for example, has ex- perienced a compound growth rate of over 30% in the past 15 years, while the use of aluminium sheet in Japan only increased at the rate of 14% per annum. Largely because of its combined extrusion- anodising capability, Indalex's services had been very attractive to the construction industry, since these companies required protective coatings on virtually all of their purchased extrusions. By 1977 about two-thirds of Indalex's total sales were to construction companies, with other major in- dustries like transportation and engineering ac- counting for less than 10% each. Any change in the percentage of total construction-related work would imply a change in the capacity balance - between extrusion and anodising. Indalex sales were handled by a 10-man 1 outside sales force (who were thought of as "Cus- tomer Liaison Engineers"), all of whom had en- gineering experience and were paid entirely by salary. Its major customer fell into two main groups: suppliers of windows, doors and patio 17 doors to the prime (new construction) building industry, and companies who were in the "home- improvement" business. About 45% of the total sales turnover derived from aluminium extrusions in the U.K. was pro- duced by three companies: Indalex, RTZ Extru- ders Ltd. (another member of the RTZ-Pillar group), and a subsidiary of Alcan. Indalex and its sister company, which was located in Widnes (about 115 miles from Cheltenham, see Exhibit 2), each owned three extrusion presses, while Alcan owned 12. It was estimated that the total extrusion capacity in the U.K. and Wales was about 160,000 metric tonnes per year, but that industry output was running at a rate of only 120,000 tonnes per year in late 1977. Indalex, however, was now operating at close to 95% of its capacity, and so its primary current objective was to juggle its capacity to meet its customers' needs as well as possible, while slowly upgrading its sales by culling out low-profit prod- ucts and poorer customers. The company's sales- men were currently spending a considerable proportion of their time doing two things that few salesmen like to do: rationing customers, and planning ahead. Starting in October the salesmen had contacted the top 20-30% of their customers to determine what their likely requirements would be during the coming year. It appeared in late 1977 that Indalex could increase its sales by 20% during 1978-if it had the capacity. In order to free up capacity for "good" customers, the company had recently reduced the number of customers who did not pay their bills within 30 days beyond their agreed credit period. Peter Mcllwraith attributed Indalex's suc- cess, both past and current, to its competitive strategy which, he said, was "based on three words: service, service, service." Indalex competed less on the basis of price than on its quality and flexibility. "We view our factory as being an integral part of our customer's factory. We have very close working relationships with our cus- tomers, and try to respond to their needs even when they give us very short notice." For example, customers were allowed to specify die changes up to two days before their order was due to be run and Indalex was willing to accept much smaller orders than did most of its competitors. When asked how he could continue to re- spond to requests for special service when he was operating so close to capacity, Mellwraith replied that "you have to know who has the slack and who doesn't; we've done enough favors for our customers when they really needed help that when they have some room to spare they don't mind if we shuffle their order around so that somebody else can squeeze in-but to do that properly, we I have to know their business almost as well as they do." Despite this special knowledge and cooperation, he admitted that "for 30 weeks of the year our production planning section is stretched to the limit." IV. Decisions Facing Indalex in Late-1977 Given the current capacity constraint and all forecasts of future demand available to Peter Mellwraith it seemed obvious that Indalex should move quickly to increase its production capacity. But there were several ways in which Indalex could expand, each with its own set of costs and benefits, and it might be unwise to try and do more than one thing at a time. On the other hand, if no additional capacity was provided, the com- pany had no recourse other than to chop off some of its long-time customers. This would not only be painful by itself, but might have disagreeable side effects: the salesmen who handled these accounts might feel slighted, and the remaining customers might decide that Indalex "wasn't will- ing to grow with us," as Peter Mellwraith put it Trying to fill the capacity gap through subcon- tracting out some of his work might be a short term solution, but Mcllwraith was also uneasy about the impact on customer relations that too much reliance on subcontractors would have. The most obvious capacity constraint was in extrusion. The problem with increasing extruder capacity was that the minimum size increment that was available was another press-repre senting roughly a 33% increase in capacity. More- over, in order to run this new press efficiently it would have to be specialized for one, or possibly two, billet diameters. Although some shuffling around of orders between machines was possible this could still have the effect of drastically in creasing the capacity for certain sized billets while not serving to relax substantially the capacity constraint on other diameters. Finally, new presses were very expensive: Peter Mellwraith estimated that the total in-- stalled cost would be just over 1,000,000, or nearly 50% of Indalex's net Fixed Assets. Interest rates for long term money were running 9-10% (down from 17% two years earlier), but this cost was balanced by the fact that the cost of capital equipment was rising at a rate of 12-15% per year. The overall rate of inflation for the U.K. was predicted to be in the range of 8-12% through the early 1980's. If demand grew as expected there promised to be little difficulty in filling the capacity of the new press within a 3 year period, but recently Mellwraith had begun to sense that the growth of the U.K.'s economy might not be as rapid as most people had been predicting a few months earlier. The entire European Economic Commu- nity, in fact, appeared to be stagnating, and so he was forced to consider what he would do with the new press if he could not fill it naturally with new demand. He could quickly pull in about 200 tonnes/year that were being subcontracted out, for example, and probably attract another 500 tonnes of small batch size business that he was. currently turning down because of his capacity squeeze. In addition he could "buy demand" by submitting a low bid for one or two very high. volume orders. In this way he could probably get close to the 1500-2000 tonnes required for a breakeven operation, but at the risk of temporarily compromising his company's long term marketing strategy and reputation. Complicating the problem was the fact that if he were to maintain his current balance of operations, he should add a new anodising plant, containing a minimum of three new tanks with a combined annual capacity of 2000 tonnes. This would cost another 800,000. Filling this new capacity would present less of a problem, because two of his present anodising tanks were becoming obsolete and would have to be replaced shortly anyway. But the question remained: was this the time to do it? Over the long term Mcllwraith was optimis- tic that he could fill the capacity of the new press and anodising plant, almost irrespective of the temporary dips and rises in the U.K. economy. 1. Indalex Ltd. This would require some focused sales planning. of course: beginning by estimating exactly how much of what kind/size capacity would be avail- able at what points in time, then selecting prod- ucts and customers who were likely vehicles for filling this capacity, and then moving aggressively to get their business. This necessitated some determined long-range thinking, but was essen- tially how Indalex had built its current business to its present robust state during most of which time it had been facing comparable over-capacity in the industry, and comparable sluggishness in the overall economy. Indalex also had the option of expanding in another direction, with less marketing risk It was currently generating somewhat less than 5000 tonnes of aluminium scrap per year out of its current operations (see Exhibit 3). This scrap was converted back into reusable aluminium bil- lets under a "tolling" arrangement with an outside company. Mellwraith had become intrigued with the possibility of buying his own recycling plant, which would allow Indalex to reprocess its own scrap aluminium. The equipment that he was looking at was very modern, and would cost about 690,000. It would be housed in a warehouse building that was adjacent to Indalex's plant site. Purchasing and modifying this building would cost an addi- tional 167,000. The plant would conform strictly to the latest pollution-control regulations, and i would not release any toxic fumes or smoke to the atmosphere. The estimated operating savings per year are detailed in Exhibits 6a and 6b. In addition to these monetary savings, additional advantages to Indalex included the following: 1. Total capacity of the recycling plant, based on the assumptions of round-the-clock operation 5 days a week, 48 weeks a year, and a 90% efficiency rate, would be approximately 10,500 tonnes per year. This implied that Indalex would be able to handle all of its reprocessing needs through the late 1980's. Another 40% increase in capacity could be provided simply by moving to a 7-day-per-week operation. 2. The proposed plant utilized two separate re- melt furnaces, which permitted Indalex to con- tinue operations at a reduced rate if one of the furnaces went out of operation. 19 did not transfer ownership of the scrap it produced, so the cost of the capital tied up in scrap inventories would not be affected. In fact, its scrap inventories might even decrease as its scrap "pipeline" contracted and it was able to tailor the billet sizes it produced to its changing extrusion requirements. Other in- ventories (of various additives) might increase, but only on the order of 50,000 per year. Once the new plant was working properly, it would be relatively easy to manage. Since Indalex currently purchased 8 grades of alumin 1985 7480 192 1436 7480 8844 3. It gave Indalex total control over its supply of secondary billet (about one-third of its total aluminium usage), and freed it from having to depend on an outside company. This was ex- pected to become increasingly important as the demand for aluminium increased faster than world production capacity, suggesting the pos- sibility of a world shortage of ingots in the early-to-mid 1980's. 4. In times of billet shortage, Indalex would have the option of buying raw aluminium ingots and converting them to billets itself. 5. Under its current tolling arrangement, Indalex EXHIBIT 6A New Recycling Plant 1. BASE CASE: NO PLANT Internal Scrap Generated (tons)" Tolling Cost/ton (adj. for infl.) Total Tolling Charge (000's) II. NEW RECYCLING PLANT Internal Scrap Generated (tons) Implied Input Variable Cost/ton 220 320 Total Variable Costs Total Annual Costs 112 152 332 472 Total Operating Costs Plus Furnace eline 24 496 318 624 885 Savings Less Capital Allowances (for tax purposes) 822 Additional Taxable Profit From (504) 439 Operation 624 885 (262) 228 324 460 Tax Paid (Recovered), at 52% After Tax Profit (242) 211 300 425 Notes: Scrap tons are estimated from estimated sales tons, according to business plan, and assuming that scrap remains in the same proportion to total sales as is the case currently. Proper furnace operation requires the addition of about 20% virgin aluminum to the scrap charge, as well as trace amounts of magnesium and silicon. A 2% melt loss is also factored in. These costs are described in more detail in Exhibit 6b. Inflation has been factored into them, so they represent current. best estimates of the osts that will be experienced in each year. ESTIMATED OPERATING COST OF PROPOSED RECYCLING PLANT Selected Years 1979 1981 1983 5371 5922 6785 121 141 165 650 835 1120 5371 5922 6785 6350 7002 8022 (000's) 34.60 37.12 260 136 396 439 39.82 42.73 380 171 551 EXHIBIT 6B New Recycling Plant ESTIMATED VARIABLE COST/TON (1979) 1979 Consumable materials other than scrap and virgin ingot Energy 8.35 19.06 Other (maintenance, royalties, misc.) 2.68 Total Variable Costs per Ton Incl. Contingency at 15% 30.09 34.60 ESTIMATED ANNUAL FIXED COSTS (2000's) 1979 Direct labor and employee benefits Indirect labor Insurance Allocated overhead 136 Incl. Contingency at 15% Costs are best estimates, based largely on data provided by the equipment supplier. This provides a cushion against unforeseen or underestimated costs. Optimal efficiency is achieved if the furnace is fully crewed for 24 hour operation during the time it is in use. Although it will initially be used only at 50% capacity, the plan is to staff it for continuous operation and then shut it down periodically. During shut down times the 14-man workforce will be assigned to other tasks. Labor cost increases over time, therefore, will arise from wage rate increases rather than from increases in the number of workers employed. ium, it would have to separate the scrap it pro- duced and process it separately to preserve purity, but this presented no major problems. Mc- Ilwraith's superiors in the Pillar Group had al- ready informally agreed to let him buy this new smelter if he decided to recommend it, both on the basis of its own internal economics and the valuable information that would be generated for Pillar's other extrusion companies. But filling the remaining capacity of the remelt plant would present Indalex with new marketing problems, 61 13 16 97 1981. 9.71 19.57 3.00 32.28 37.12 1981 112 .a 75 16 9 18 118 and it probably did not have the personnel re- sources to do everything at once.. The question that Peter Mcllwraith pon- dered in late 1977 was: which of the various options in front of him should he choose to do first? Since each of the three alternatives (a new extrusion press, a new anodising plant, or the recycling plant) would require 10-12 months to install, a decision had to be made immediately in order for the new piece of equipment to be avail- able by the beginning of 1979. 01