Question: Read the above and answer the following 3 questions: Thank you! Social media is pervasive in American society. From online dating to text messaging, around

Read the above and answer the following 3 questions:

Thank you!

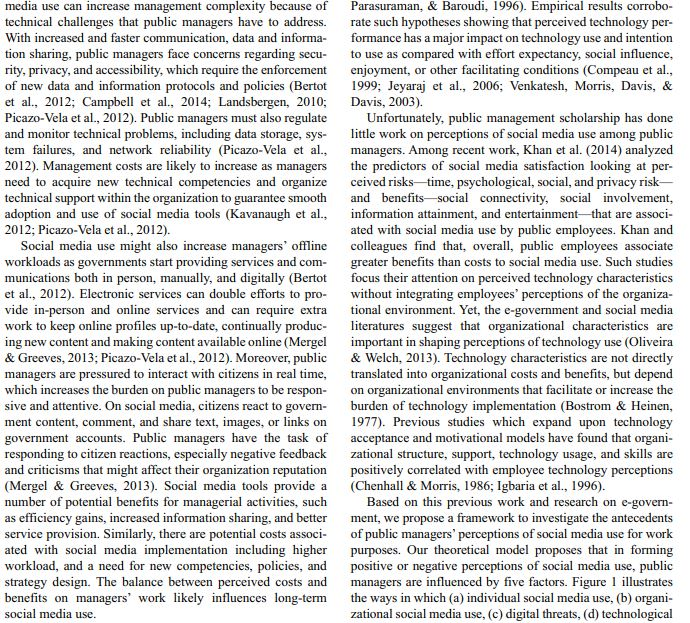

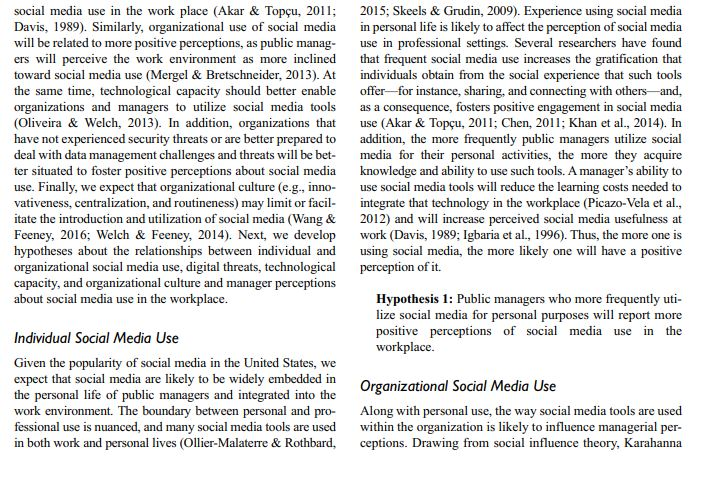

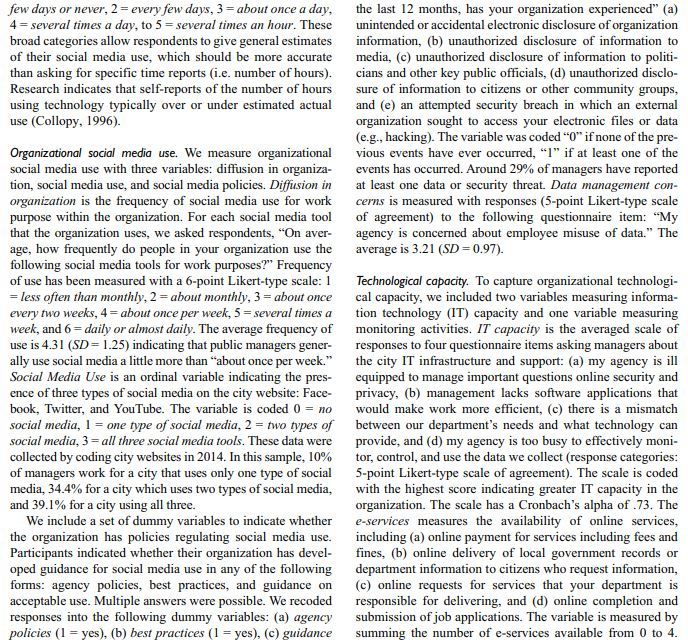

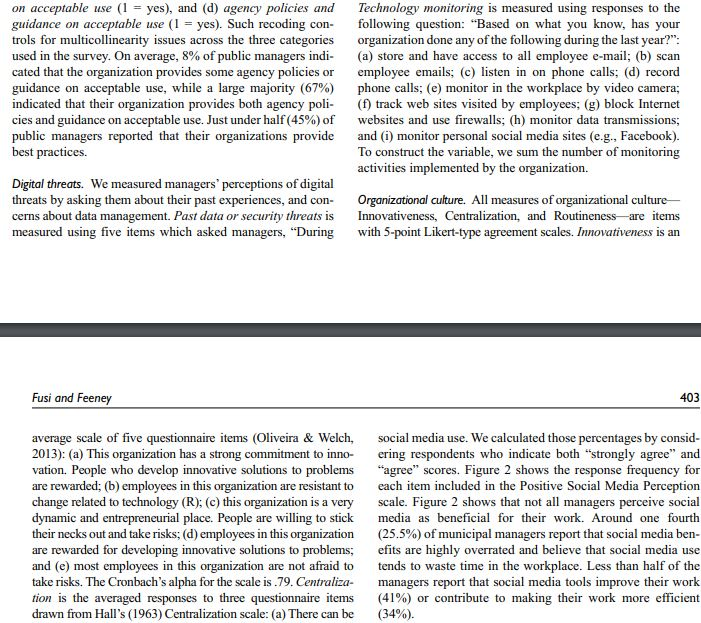

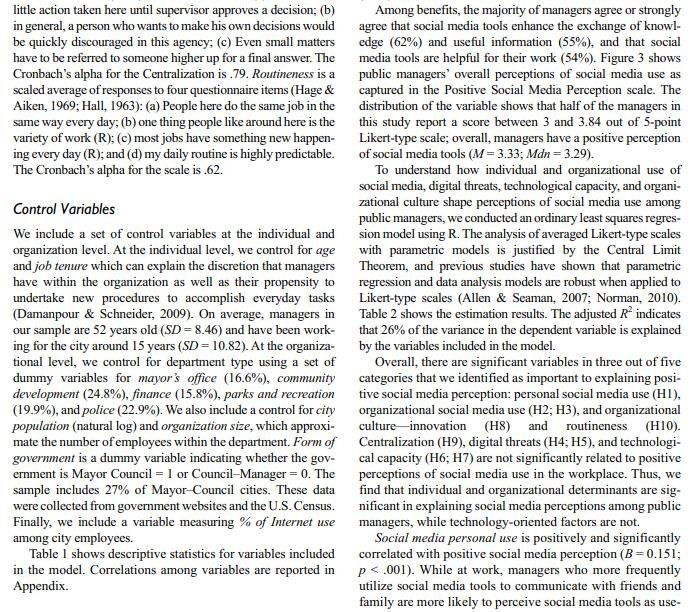

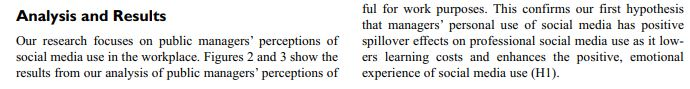

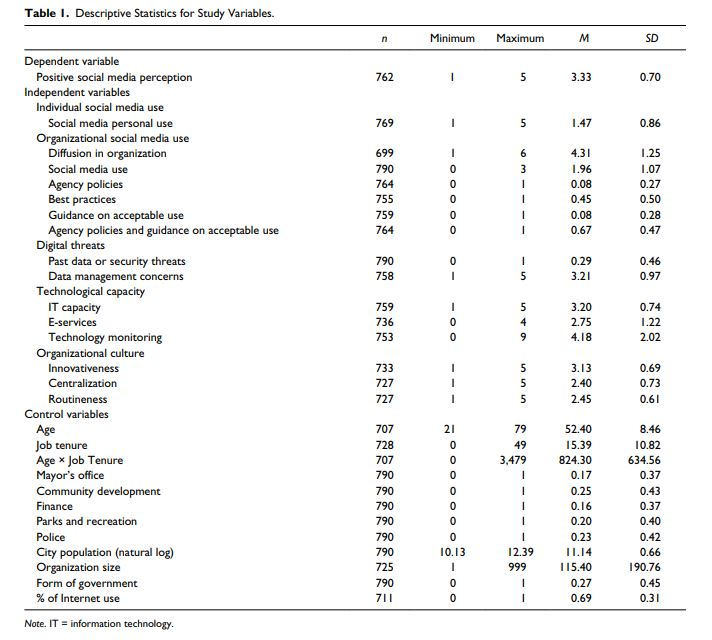

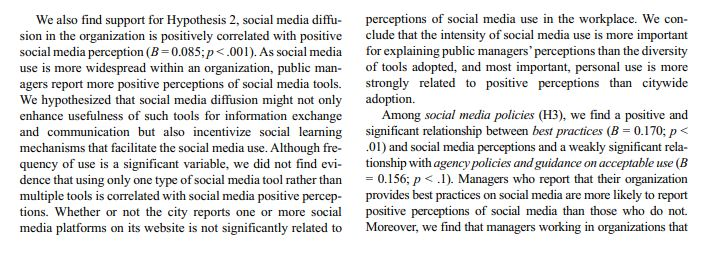

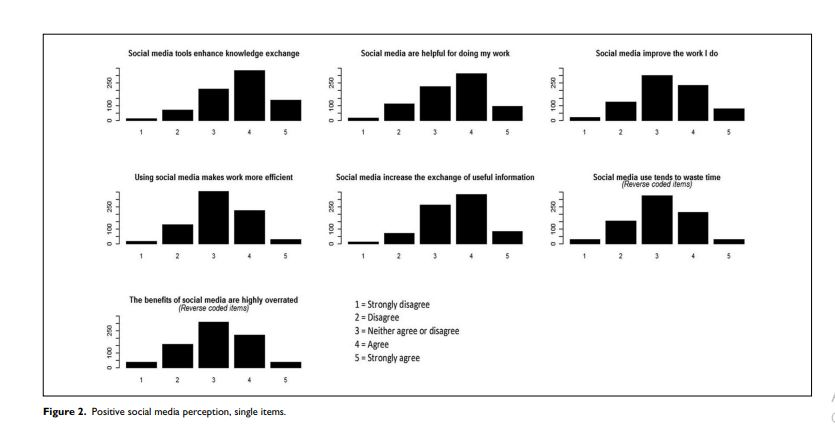

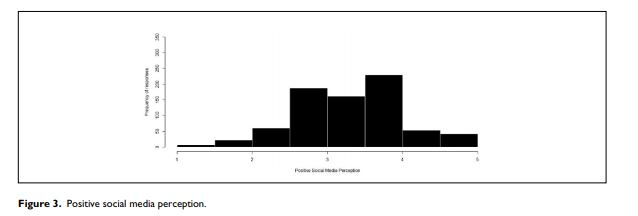

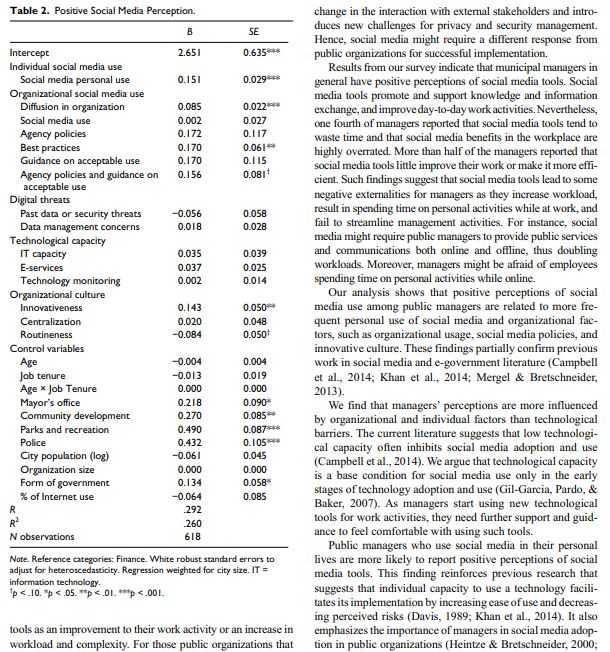

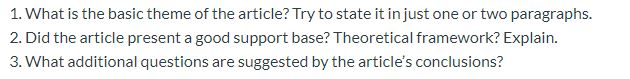

Social media is pervasive in American society. From online dating to text messaging, around 65% of American adults use social media in their everyday life (Perrin, 2015). This trend is global with 1.23 billion (Sedghi, 2014), 320 million (Twitter, 2015), and 1 billion (Billboard Staff, 2015) people worldwide using Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, respec- tively, on a monthly basis. Social media are a group of "Internet-based technologies that build on the ideological and technical foundations of Web 2.0" (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010, p. 61) to leverage the social and interactive nature of technology. Social media tools allow two-way information exchange between individuals or groups via videos, images, texts messages, and podcasts, and include not only free applications such as Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, YouTube and Flickr but also fee-driven services such as Basecamp or Ning. Initially, social media tools were designed for nonwork- related activities such as socializing, sharing photos, and connecting with friends (Mergel & Bretschneider, 2013). In fact, the majority of Americans report using social media pri- marily for staying in touch with friends and family or con- necting with lost friends (Smith, 2011). As social media has become a part of everyday life, organizations have sought to integrate these tools into work life. Public, private, and non- profit organizations have progressively increased their social media presence and usage to improve their relationships with customers and citizens, promote their corporate identity, and improve their communication (Klang & Nolin, 2011; Trainor, Andzulis, Rapp, & Agnihotri, 2014). In the public sector, government has progressively expanded its online presence by opening accounts on Facebook and Twitter. As people become more accustomed to using social media, they expect government to do the same. Moreover, social media has raised expectations for a variety of positive outcomes within government, such as enhancing transparency, accountability, and collaboration within and across public agencies, encour- aging citizen participation, and improving public service provision (Bonson, Torres, Royo, & Flores, 2012; Campbell, Lambright, & Wells, 2014; Kim, Park, & Rho, 2015; Mergel, 2010). Public managers play a pivotal role in social media adoption and use. Some public managers have promoted social media use within their departments, with entrepreneurial public managers Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ, USA Corresponding Author: Federica Fusi, Center for Science, Technology and Environmental Policy Studies, School of Public Affairs, Arizona State University, 411 N Central Ave #750, Phoenix, AZ 85004, USA Email: ffusi@asu.edu being the first to adopt social media tools in everyday organiza- tional activities (Mergel & Bretschneider, 2013). Yet, research- ers and governments have little understanding of how public managers perceive social media use and how social media use is affecting their work, whether positively or negatively (Kavanaugh et al., 2012; Khan, Swar, & Lee, 2014). Social media tools can help managers to better and faster perform their tasks, but research has also found that privacy concerns, time wasting, and multi-tasking challenges may increase manage- ment complexity and decrease public managers' concentration (Bertot, Jaeger, & Hansen, 2012; Oliveira & Welch, 2013). For example, among American adults using online tools for profes- sional purposes, 39% report a higher flexibility in their working hours, but an almost equal percentage report that online tools have actually increased their working time (Purcell & Rainie, 2014). All in all, there appear to be ambiguous effects of tech- nology use, including social media, on work activities. We investigate how public managers perceive social media use and what factors explain manager perceptions of social media use. Public manager perception of social media use is important to understand whether social media support or hinder government activities and how managers can take advantage of such tools (Ngai, Tao, & Moon, 2015; Tsay, Dabbish, & Herbsleb, 2012). The lack of understand ing of public managers' perceptions might lead to mis- placed strategies for social media adoption or the overly optimistic belief that social media use is intrinsically posi- tive for government activities. Building on technology adoption and use theories and e-government research, we focus our attention on the role of managers' personal expe- riences with social media use and organizational factors, such as organizational use of social media, organizational culture, digital threats, and technological capacity, in shap- ing perceptions. Although individuals are often the leaders in adopting social media, we argue that the organizational environment and the level of support they receive from their organization influence their long-term perceptions. As organization leaders, managers play a pivotal role in inno- vation adoption by influencing organizational practices and policies and by creating a climate favorable to innovation and change (Damanpour & Schneider, 2009; Jeyaraj, Rottman, & Lacity, 2006; Kiron, Palmer, Phillips, & Kruschwitz, 2012). Several studies have found that technology adoption and implementation within organizations are largely determined by managers, especially their perceptions and attitudes toward technology and innovation (Karahanna & Straub, 1999), political orientation (Damanpour & Schneider, 2009), and trust toward managerial capacity (Horst, Kuttschreuter, & Gutteling, 2007). Moreover, managerial support for technol- ogy implementation positively reinforces technology impact on the organization's performance (Heintze & Bretschneider, 2000). Hence, understanding managers' relationships with and perceptions of new technologies is fundamental to pre- dicting technology adoption, use, and impact across the organization. In the case of social media, public managers have often taken an entrepreneurial position by introducing social media tools in public organizations (Klang & Nolin, 2011; Mergel & Bretschneider, 2013) and experimenting with new approaches to use social media for public service provision (Goldsmith & Crawford, 2014). However, little research has empirically examined how public managers perceive social media use in the workplace. Understanding what shapes pub- lic managers' perceptions of social media use provides insights into whether government adoption of social media is leading to positive outcomes for managers and, if so, how to support social media use without compromising public man- agers' workload. Dissatisfaction is quite common during technology implementation as actual use might not meet user expectations (Bryer & Zavattaro, 2011; Picazo-Vela, Gutirrez-Martinez, & Luna-Reyes, 2012). Government managers may perceive social media as an opportunity to foster innovation and experimentation, but they might also perceive social media as an additional burden. We combine data from a 2014 national survey adminis- tered to 2,500 U.S. public managers in 500 U.S. cities, U.S. Census data, and data collected from city websites to test our hypotheses. We find that personal use of social media has a strong positive effect on public managers' perceptions of social media use. Moreover, public managers are more likely to report positive perceptions of social media use whether they work for more innovative organizations, organizations which use social media tools more frequently and organiza tions where best practices are available to guide public man- agers in the implementation and use of social media. Finally, we show that technological factors and digital threats do not influence public managers' perceptions of social media use. The e-government literature recognizes that social media can help public employees to connect to one another, build social capital, maintain awareness of professional issues, and share information (Cao, Vogel, Guo, Liu, & Gu, 2012; Skeels & Grudin, 2009). Moreover, efficiency gains may arise from the simplification of everyday activities, including public service provision and design, and faster communication with the public and other stakeholders. Social media provides a platform to local governments to interact with citizens, col- lect feedback on public services, and better target public ser- vice delivery (Khasawneh & Abu-Shanab, 2013; Kuzma, 2010; Perlman, 2012; Picazo-Vela et al., 2012). In addition, social media tools might facilitate information dissemination within the organization (Chun, Shulman, Sandoval, & Hovy, 2010; Khan, 2015) and provide access to diverse information by connecting local governments with external stakeholders, including citizens, other public agencies, and various levels of government (Khan et al., 2014). Information diversity Literature and Hypotheses Research has widely investigated the role of managers in the adoption of new technologies, such as social media. Fusi and Feeney 397 may improve decision-making processes and support mana- gerial choices (Bertot et al., 2012). Mergel and Greeves (2013) argued that setting up a social media account and using social media are relatively easy and costless activities. As compared with other technologies. which require large investments and organizational resources, social media adoption can be a low cost, bottom-up activity initiated by a single manager. However, widespread social media use within the organization may lead to managerial costs and might increase inefficiency rather than streamline organizational activities (Bryer & Zavattaro, 2011). Social use such technology (Davis, 1989; Featherman & Pavlou, 2003). Employees who perceive technology tools as more useful for their work are more willing to use them. Other theories note that expectations toward a technology perfor- mance are positively related to technology use. The Theory of Reasoned Action and Theory of Planned Behavior link technology use and intention to use to technology-expected outcomes (Compeau, Higgins, & Huff, 1999; Madden, Ellen, & Ajzen, 1992). Similarly, Motivational Models suggest that believing technology use will help achieve desired outcomes increases willingness to use a new technology (Igbaria, media use can increase management complexity because of Parasuraman, & Baroudi, 1996). Empirical results corrobo- technical challenges that public managers have to address. rate such hypotheses showing that perceived technology per- With increased and faster communication, data and informa formance has a major impact on technology use and intention tion sharing, public managers face concerns regarding secu to use as compared with effort expectancy, social influence, rity, privacy, and accessibility, which require the enforcement enjoyment, or other facilitating conditions (Compeau et al., of new data and information protocols and policies (Bertot 1999; Jeyaraj et al., 2006; Venkatesh, Morris, Davis, & et al., 2012; Campbell et al., 2014; Landsbergen, 2010; Davis, 2003). Picazo-Vela et al., 2012). Public managers must also regulate Unfortunately, public management scholarship has done and monitor technical problems, including data storage, sys little work on perceptions of social media use among public tem failures, and network reliability (Picazo-Vela et al., managers. Among recent work, Khan et al. (2014) analyzed 2012). Management costs are likely to increase as managers the predictors of social media satisfaction looking at per- need to acquire new technical competencies and organize ceived riskstime, psychological, social, and privacy risk- technical support within the organization to guarantee smooth and benefits-social connectivity, social involvement, adoption and use of social media tools (Kavanaugh et al., information attainment, and entertainmentthat are associ- 2012; Picazo-Vela et al., 2012). ated with social media use by public employees. Khan and Social media use might also increase managers' offline colleagues find that, overall, public employees associate workloads as governments start providing services and com greater benefits than costs to social media use. Such studies munications both in person, manually, and digitally (Bertot focus their attention on perceived technology characteristics et al., 2012). Electronic services can double efforts to pro without integrating employees' perceptions of the organiza- vide in-person and online services and can require extra tional environment. Yet, the e-government and social media work to keep online profiles up-to-date, continually produc- literatures suggest that organizational characteristics are ing new content and making content available online (Mergel important in shaping perceptions of technology use (Oliveira & Greeves, 2013; Picazo-Vela et al., 2012). Moreover, public & Welch, 2013). Technology characteristics are not directly managers are pressured to interact with citizens in real time, translated into organizational costs and benefits, but depend which increases the burden on public managers to be respon on organizational environments that facilitate or increase the sive and attentive. On social media, citizens react to govern- burden of technology implementation (Bostrom & Heinen, ment content, comment, and share text, images, or links on 1977). Previous studies which expand upon technology government accounts. Public managers have the task of acceptance and motivational models have found that organi- responding to citizen reactions, especially negative feedback zational structure, support, technology usage, and skills are and criticisms that might affect their organization reputation positively correlated with employee technology perceptions (Mergel & Greeves, 2013). Social media tools provide a (Chenhall & Morris, 1986; Igbaria et al., 1996). number of potential benefits for managerial activities, such B ased on this previous work and research on e-govern- as efficiency gains, increased information sharing, and betterm ent, we propose a framework to investigate the antecedents service provision. Similarly, there are potential costs associ- of public managers' perceptions of social media use for work ated with social media implementation including higher purposes. Our theoretical model proposes that in forming workload, and a need for new competencies, policies, and positive or negative perceptions of social media use, public strategy design. The balance between perceived costs and managers are influenced by five factors. Figure 1 illustrates benefits on managers' work likely influences long-term the ways in which (a) individual social media use, (b) organi- social media use. zational social media use, (c) digital threats, (d) technological A significant body of research has accumulated evidence that perceptions of a technology's impact on work perfor- mance are an important antecedent of its acceptance and use. Technology acceptance models (TAMs) argue that perceived technology usefulness significantly drives the propensity to capacity, and (e) organizational culture are related to public managers' perceptions of social media use. We expect that public managers who more frequently use social media in their personal lives will benefit from social media knowledge and expertise and will report more positive perceptions of American Review of Public Administration 48(5) Individual Social Media Use Organizational Social Media Use Diffusion in Oreanization Social Media Policies Digital Threats Past Date or Security Threats Data Management Concerns Positive Social Media Perception Technological Capacity IT Capacity Technology Monitoring Organizational Culture Innovativeness Centralization Routineness Control Variables Age Job Tenure Department Type Organization Size City Population Form of Government Internet Use social media use in the work place (Akar & Topu, 2011; Davis, 1989). Similarly, organizational use of social media will be related to more positive perceptions, as public manag- ers will perceive the work environment as more inclined toward social media use (Mergel & Bretschneider, 2013). At the same time, technological capacity should better enable organizations and managers to utilize social media tools (Oliveira & Welch, 2013). In addition, organizations that have not experienced security threats or are better prepared to deal with data management challenges and threats will be bet- ter situated to foster positive perceptions about social media use. Finally, we expect that organizational culture (e.g., inno- vativeness, centralization, and routineness) may limit or facil itate the introduction and utilization of social media (Wang & Feeney, 2016; Welch & Feeney, 2014). Next, we develop hypotheses about the relationships between individual and organizational social media use, digital threats, technological capacity, and organizational culture and manager perceptions about social media use in the workplace. 2015; Skeels & Grudin, 2009). Experience using social media in personal life is likely to affect the perception of social media use in professional settings. Several researchers have found that frequent social media use increases the gratification that individuals obtain from the social experience that such tools offer for instance, sharing, and connecting with others and, as a consequence, fosters positive engagement in social media use (Akar & Topu, 2011; Chen, 2011; Khan et al., 2014). In addition, the more frequently public managers utilize social media for their personal activities, the more they acquire knowledge and ability to use such tools. A manager's ability to use social media tools will reduce the learning costs needed to integrate that technology in the workplace (Picazo-Vela et al., 2012) and will increase perceived social media usefulness at work (Davis, 1989; Igbaria et al., 1996). Thus, the more one is using social media, the more likely one will have a positive perception of it. Hypothesis 1: Public managers who more frequently uti- lize social media for personal purposes will report more positive perceptions of social media use in the workplace. Individual Social Media Use Given the popularity of social media in the United States, we expect that social media are likely to be widely embedded in the personal life of public managers and integrated into the work environment. The boundary between personal and pro- fessional use is nuanced, and many social media tools are used in both work and personal lives (Ollier-Malaterre & Rothbard, Organizational Social Media Use Along with personal use, the way social media tools are used within the organization is likely to influence managerial per- ceptions. Drawing from social influence theory, Karahanna and Straub (1999) suggested that coworker behaviors and perceptions, especially those of peers and supervisors, are likely to affect an individual's technology perception. Individuals within the same organization are more likely to view technology adoption as useful when they see others reporting a positive experience with such technology (Schmitz & Fulk, 1991). Social influence is amplified in the case of social media tools whose primary aim is communica- tion and information exchange, both requiring input and response from multiple users (Leonardi, Huysman, & Steinfield, 2013). Given the nature of social media, there are strong incentives for a user to recruit other users within one's work network. Social media will provide greater benefits within organizations where more individuals use them, thus allowing organizations to exploit social media benefits, such as communication, coordination, and social capital building (Khan et al., 2014; Leonardi et al., 2013). Hence, we expect that when other employees are currently using social media tools within the organization, public managers will report more positive perceptions of social media. Digital Threats Risk is an important influence on managerial choices, especially when it comes to the adoption of new technologies (Landsbergen, 2010). Although social media policies can help to ease manage- rial concerns about technology use, they may not be sufficient for reducing perceived risks associated with social media use. Social media risk management is a key issue in the adoption of social media tools within public organizations (Landsbergen. 2010; Webber, Li, & Szymanski, 2012). Kavanaugh and col- leagues (2012) and Khan and colleagues (2014) found that cybersecurity is one of the most critical barriers for social media use in goverment Cybersecurity refers to perceived risk of online network exposure to the world (Featherman & Pavlou, 2003) and unauthorized disclosure of data and personal informa- tion. Cybersecurity issues might result in a loss of reputation, legal contentions, and other negative consequences (Webber et al., 2012). If public managers perceive social media use as risky, they will be less likely to view social media use in the workplace positively. Managers will feel that social media is a potential threat to their work and to their constituencies, as it increases the risk of unintended data disclosures (Campbell et al., 2014). In some cases, managers might have already expe- rienced data or security leaks. Such previous experience might also negatively affect public managers' perceptions of such tools. Hypothesis 2: Public managers who report higher organi- zational use of social media tools will report more posi- tive perceptions of social media in the workplace. Hypothesis 4: Public managers who report increased concerns about data management will report less positive perceptions of social media use. Hypothesis 5: Public managers who report previous experience with data or security threats will report less positive perceptions of social media use. As the number of people using social media grows and its usage becomes more frequent, organizations must establish common rules to avoid misuse, reduce privacy risks, and pre- vent security problems (Bonson et al., 2012; Mergel & Bretschneider, 2013). Although in the adoption stage the absence of regulation promotes entrepreneurship and experi- mentation (Mergel & Bretschneider, 2013), in the long term, policies and guidelines are needed to manage and bound con- cerns about privacy and data misuse (Campbell et al., 2014; Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010). We argue that social media policies might have a positive effect on public managers' perceptions. Social media poli- cies create a safe environment for social media use by setting standard operating procedures that reduce the amount of time and attention required to resolve failures and errors derived from social media misuse (Khan et al., 2014: Kiron et al., Technological Capacity Technology capacity is the organization's ability to mobilize IT resources and support (Nah & Saxton, 2013). Technology capacity has a positive effect on social media and e-government use as it increases the tools that public managers can deploy, and reduces implementation and leaming costs by providing ade- quate support to public managers and employees (Feeney & 2012: Mergel & Bretschneider, 2013). For instance, social media policies simplify social media use by driving and bounding its scopes and applications, such as the separation between professional and personal use (Picazo-Vela et al., 2012: Skeels & Grudin, 2009), or by providing examples of social media uses (i.e., best practices). Thus, while flexibility is important for innovation, we expect that in public sector environments, guidance about social media use will better enable managers to utilize and harness the potential of social media. Welch, 2016; Oliveira & Welch, 2013). In fact, managers in public and nonprofit organizations report that low organization technological capacity and staff expertise are serious barriers to social media adoption and use (Campbell et al., 2014). When organizations have low technology capacity, public managers must learn to use social media by themselves and cannot access organizational support in using such tools, thus increasing costs associated with social media use. As such, we expect that public managers in organizations with higher technology capacity will report more positive perceptions of social media use. Hypothesis 3: Public managers who report that their organizations have social media policies will report more positive perceptions of social media use. Hypothesis 6: Public managers who report higher organi- zational technology capacity will report more positive perceptions of social media use. 400 American Review of Public Administration 48(5) Public organizations might actively monitor social media use or more broadly monitor Internet-related activities by, for example, checking employee emails, blocking access to social media and personal websites, or monitoring data trans- mission and online activities. From the employer perspec- tive, online monitoring limits the misuse of the Internet and Internet-based technologies and helps the organization pre- vent productivity losses due to employees wasting time online (Griffiths, 2010; Young, 2010). As Landsbergen (2010) noted, monitoring social media activities might be fundamental to avoid the mistaken publication of inappropri- ate content (i.e., politically sensitive information) and to dis- courage employees from misusing social media. Feeney, 2016; Welch & Feeney, 2014). Hence, the organiza- tional culture innovativeness, centralization, and routine- ness in which social media activities are embedded will likely affect the overall perceptions of social media use among public managers. Innovativeness is defined as "the organizational) propen- sity to accept innovations" (Oliveira & Welch, 2013, p. 3). Innovative organizations are more likely to engage in risk- taking behaviors and adopt and implement new technology, such as social media (Powell & Grodal, 2005). Oliveira and Welch (2013) found that innovative public organizations are more likely to use social media for government tasks, such as disseminating information, collecting feedback on public ---- --- - - ---- policies, and collaborating internally. Moreover, innovative organizations are more likely to adapt their practices to inno- vation (Thompson, 1965). Social media use requires design- ing new managerial procedures and building of new managerial skills and competences (Mergel & Greeves, 2013), which significantly change organizational culture and practices (Picazo-Vela et al., 2012). We hypothesize that more innovative organizations are increasingly likely to accept the introduction of social media use for work purposes and will more actively encourage and support social media use. Thus, public managers who report working for innovative public organizations will be more likely to take advantage of social media use and apply social media tools to their tasks. From the employee perspective, monitoring practices might negatively affect satisfaction, trust, productivity, and engage ment, and can be perceived as an invasion of privacy and a threat to autonomy (Alder, Schminke, Noel, & Kuenzi, 2007; Choudhury, 2008; West & Bowman, 2016). Over-monitoring employee activities can reduce trust toward the organization and increase stress, workload, and perceived organization injustice (Grant & Higgins, 1989, Kallman, 1993; Oz, Glass, & Behling, 1999). As such, we might expect that organizational monitoring will decrease the benefits that public managers derive from social media use. Monitoring increases barriers to using social media in flexible and innovative ways while also increasing the psychological costs of using such tools. Moreover, monitoring negatively affects the likelihood of data and information sharing and intemal electronic collaboration among colleagues. However, studies of social media use in public organizations suggest that monitoring might have a positive impact on social media perceptions. Monitoring of social media use is a way for organizations to reduce perceived risks related to social media use by preventing misuse, information leaks, and privacy issues (Meijer & Torenvlied, 2016). Moreover, in the case of smaller municipal governments, the ability to monitor digital activity is likely a key indicator of technological and management capac- ity. The governments included in this study are relatively small, making the monitoring of digital activity a resource-intensive task. We expect that managers who report monitoring of online activities are more likely to be in organizations where there are clear rules and regulations about technology use and higher technological capacity, thus resulting in managers with more sophisticated levels of technology use, including social media, and, therefore, managers who are more likely to have positive perceptions of such technologies. Hypothesis 8: Public managers who perceive their orga- nizations as more innovative will report more positive perceptions of social media use. Researchers have consistently argued that implementing new technologies, such as social media, is easier in decentral- ized organizations where managers have the necessary auton- omy and decision-making authority to guide the organizational change (Landsbergen, 2010) and adjust organizational practices (Li & Feeney, 2014). When introducing social media tools, managers need to adapt their daily work routines according to new online activities and opportunities (Picazo-Vela et al., 2012). Meijer and Torenvlied (2016) found that Twitter use for external communication and information sharing was more effective in decentralized organizations where individuals could take the initiative on when and how to use Twitter for commu- nicating with their constituencies. By promoting the autono- mous use of social media tools, decentralized organizations increase opportunities to learn and experiment with social media tools and facilitate the design of customized social media prac- tices. Thus, we expect that decentralized organizations will allow for more experimentation and learning, and that managers in decentralized organizations will report more positive percep- tions of social media use. Hypothesis 7: Public managers who report higher organi- zational monitoring of online activities will report more positive perceptions of social media use. Organizational Culture LIQUIS UI SUURI III u use. Organizational Culture Organizational culture strongly predicts technology adoption in public organizations (Aiken & Hage, 1971; Damanpour & Schneider, 2009; Pandey & Bretschneider, 1997; Wang & Hypothesis 9: Public managers who perceive their orga- nizations as more centralized will report less positive per- ceptions of social media use. Fusi and Feeney 401 having the characteristic of being social and interactive in nature-allowing, but not requiring, two-way information exchange between individuals or groups, such as between individuals, public employees and citizens. Examples of commonly used social media tools include: Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, LinkedIn, Gov Loop, Ning, Basecamp, Tweetdeck, Jive, Tibbr, Yammer and SocialCast. Finally, we argue that managers with more standardized and routinized tasks might see social media as less useful for their job and as a waste of time. Job routineness pro- vides less opportunity for innovation adoption (Aiken & Hage, 1971), slows down technology adoption in public organizations (Li & Feeney, 2014), and reduces perceived positive outcomes from technology use (Welch & Feeney, 2014). Public managers who perform routinized activities will have fewer incentives to experiment with social media use and less opportunities to innovate their daily activities taking advantage of social media characteristics. As such, when performing routinized tasks, public managers might perceive social media use as an additional burden. Although we hypothesize that more innovative and decentralized organizations are more likely to accept social media use for work purposes, and will more actively encourage social media use, we state that managers performing routinized activities will report lower positive perceptions of social media use. Because our focus is on understanding how social media, as a group of tools that share similar characteristics, are related to public managers' perceptions, we do not differenti- ate between social media type and we broadly refer to social media use for any work activity (Cao et al., 2012; Leftheriotis & Giannakos, 2014). Dependent Variable: Positive Social Media Perception The dependent variable, positive social media perception, is partially based on the perceived usefulness scale developed in TAM studies. Similar to Davis (1989) and Karahanna and Straub (1999), we asked public managers about how social media affects their job performance, productivity, and time wasting. In addition, we asked perception of social media use Hypothesis 10: Public managers who perceive their orga- nizations as more routinized will report less positive per- ceptions of social media use. for information and knowledge exchange, a primary function of social media tools (Bonson et al., 2012; Leonardi et al., 2013). Respondents rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale their level of agreement (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree) with the following statements: Data and Method We combine data from the U.S. Census, city websites, and a national survey conducted in 2014 by the Center for Science, Technology and Environmental Policy Studies at the Arizona State University. A survey is an appropriate method for this study, as we are interested in investigating managers' percep- tions of social media use. Individual perceptions are relevant to the choice of using a new technology or not, as shown in previous studies (Davis, 1989Horst et al., 2007; Karahanna & Straub, 1999). The survey was administered to public managers in 500 local governments with populations ranging from 25,000 to 250,000 inhabitants. Because there are fewer large cities in the United States, we sampled the census of cities (184) with populations between 100,000 and 250,000 inhabitants and drew a random sample of smaller cities (316) with popula- tions of 25,000 to 99,999 residents. For each city, five man- agers were selected to participate to the study, one from each of the following departments: City Management, Community Development, Finance, Police, and Parks and Recreation, for a total of 2,500 managers. After removing bad addresses, vacancies, retirees, and managers who were no longer work- ing in the position, the sample was reduced to 2,461 public managers. The final response rate, calculated according to the Response Rate 2 (RR2) method from the American Association for Public Opinion Research, is 33.07% (790 respondents). The RR2 method counts partial interviews as respondents. In the survey, we defined social media in line with the literature: a. Social media enhance knowledge exchange in my or- ganization. b. Social media tools are helpful for doing my work. c. Social media tools improve the work I do. d. Social media use tends to waste time. (Reversed) e. Using social media makes work more efficient. f. The benefit of social media tools in the workplace is highly overrated. (Reversed) g. Social media tools increase the exchange of useful in- formation in my organization. The dependent variable, positive social media perception, is an average scale with a Cronbach's alpha of 89. A higher rating on the Positive Social Media Perception scale indi- cates positive perceptions of social media use. A lower score is associated with negative perceptions of social media use. Scale average is 3.33 (SD = 0.70). in Independent Variables Individual social media use. We measure Social Media Per sonal Use asking, "While at work, how often do you com- municate with friends or family using social media?" Response categories range from 1 = less often than every few days or never, 2 = every few days, 3 = about once a day, 4= several times a day, to 5 = several times an hour. These broad categories allow respondents to give general estimates of their social media use, which should be more accurate than asking for specific time reports (i.e. number of hours). Research indicates that self-reports of the number of hours using technology typically over or under estimated actual use (Collopy, 1996). the last 12 months, has your organization experienced" (a) unintended or accidental electronic disclosure of organization information, (b) unauthorized disclosure of information to media, (c) unauthorized disclosure of information to politi- cians and other key public officials, (d) unauthorized disclo- sure of information to citizens or other community groups, and (e) an attempted security breach in which an external organization sought to access your electronic files or data (e.g., hacking). The variable was coded "0" if none of the pre- vious events have ever occurred, "1" if at least one of the events has occurred. Around 29% of managers have reported at least one data or security threat. Data management con- cerns is measured with responses (5-point Likert-type scale of agreement) to the following questionnaire item: "My agency is concerned about employee misuse of data." The average is 3.21 (SD = 0.97). Organizational social media use. We measure organizational social media use with three variables: diffusion in organiza- tion, social media use, and social media policies. Diffusion in organization is the frequency of social media use for work purpose within the organization. For each social media tool that the organization uses, we asked respondents, "On aver- age, how frequently do people in your organization use the following social media tools for work purposes?" Frequency of use has been measured with a 6-point Likert-type scale: 1 = less often than monthly, 2 = about monthly, 3 = about once every two weeks, 4 = about once per week, 5= several times a week, and 6 = daily or almost daily. The average frequency of use is 4.31 (SD= 1.25) indicating that public managers gener- ally use social media a little more than about once per week." Social Media Use is an ordinal variable indicating the pres- ence of three types of social media on the city website: Face- book, Twitter, and YouTube. The variable is coded 0 = no social media, I = one type of social media, 2 = two types of social media, 3 = all three social media tools. These data were collected by coding city websites in 2014. In this sample, 10% of managers work for a city that uses only one type of social media, 34.4% for a city which uses two types of social media, and 39.1% for a city using all three. We include a set of dummy variables to indicate whether the organization has policies regulating social media use. Participants indicated whether their organization has devel- oped guidance for social media use in any of the following forms: agency policies, best practices, and guidance on acceptable use. Multiple answers were possible. We recoded responses into the following dummy variables: (a) agency policies (1 = yes), (b) best practices (1 = yes), (c) guidance Technological capacity. To capture organizational technologi- cal capacity, we included two variables measuring informa- tion technology (IT) capacity and one variable measuring monitoring activities. IT capacity is the averaged scale of responses to four questionnaire items asking managers about the city IT infrastructure and support: (a) my agency is ill equipped to manage important questions online security and privacy, (b) management lacks software applications that would make work more efficient, (c) there is a mismatch between our department's needs and what technology can provide, and (d) my agency is too busy to effectively moni- tor, control, and use the data we collect (response categories: 5-point Likert-type scale of agreement). The scale is coded with the highest score indicating greater IT capacity in the organization. The scale has a Cronbach's alpha of.73. The e-services measures the availability of online services, including (a) online payment for services including fees and fines, (b) online delivery of local government records or department information to citizens who request information, (c) online requests for services that your department is responsible for delivering, and (d) online completion and submission of job applications. The variable is measured by summing the number of e-services available from 0 to 4. on acceptable use (1 = yes), and (d) agency policies and guidance on acceptable use (1 = yes). Such recoding con trols for multicollinearity issues across the three categories used in the survey. On average, 8% of public managers indi- cated that the organization provides some agency policies or guidance on acceptable use, while a large majority (67%) indicated that their organization provides both agency poli- cies and guidance on acceptable use. Just under half (45%) of public managers reported that their organizations provide best practices. Technology monitoring is measured using responses to the following question: "Based on what you know, has your organization done any of the following during the last year?": (a) store and have access to all employee e-mail; (b) scan employee emails; (c) listen in on phone calls; (d) record phone calls; (c) monitor in the workplace by video camera; (f) track web sites visited by employees; (g) block Internet websites and use firewalls; (h) monitor data transmissions, and (i) monitor personal social media sites (e.g., Facebook). To construct the variable, we sum the number of monitoring activities implemented by the organization. Digital threats. We measured managers' perceptions of digital threats by asking them about their past experiences, and con- cerns about data management. Past data or security threats is measured using five items which asked managers, "During Organizational culture. All measures of organizational culture Innovativeness, Centralization, and Routineness are items with 5-point Likert-type agreement scales. Innovativeness is an Fusi and Feeney 403 average scale of five questionnaire items (Oliveira & Welch, 2013): (a) This organization has a strong commitment to inno- vation. People who develop innovative solutions to problems are rewarded; (b) employees in this organization are resistant to change related to technology (R); (c) this organization is a very dynamic and entrepreneurial place. People are willing to stick their necks out and take risks; (d) employees in this organization are rewarded for developing innovative solutions to problems; and (c) most employees in this organization are not afraid to take risks. The Cronbach's alpha for the scale is.79. Centraliza- tion is the averaged responses to three questionnaire items drawn from Hall's (1963) Centralization scale: (a) There can be social media use. We calculated those percentages by consid- ering respondents who indicate both strongly agree" and agree" scores. Figure 2 shows the response frequency for cach item included in the Positive Social Media Perception scale. Figure 2 shows that not all managers perceive social media as beneficial for their work. Around one fourth (25.5%) of municipal managers report that social media ben- efits are highly overrated and believe that social media use tends to waste time in the workplace. Less than half of the managers report that social media tools improve their work (41%) or contribute to making their work more efficient (34%). little action taken here until supervisor approves a decision; (b) in general, a person who wants to make his own decisions would be quickly discouraged in this agency: (c) Even small matters have to be referred to someone higher up for a final answer. The Cronbach's alpha for the Centralization is 79. Routineness is a scaled average of responses to four questionnaire items (Hage & Aiken, 1969; Hall, 1963): (a) People here do the same job in the same way every day; (b) one thing people like around here is the variety of work (R); (c) most jobs have something new happen ing every day (R); and (d) my daily routine is highly predictable. The Cronbach's alpha for the scale is .62. Control Variables We include a set of control variables at the individual and organization level. At the individual level, we control for age and job tenure which can explain the discretion that managers have within the organization as well as their propensity to undertake new procedures to accomplish everyday tasks (Damanpour & Schneider, 2009). On average, managers in our sample are 52 years old (SD = 8.46) and have been work- ing for the city around 15 years (SD= 10.82). At the organiza- tional level, we control for department type using a set of dummy variables for mayor's office (16.6%), community development (24.8%), finance (15.8%), parks and recreation (19.9%), and police (22.9%). We also include a control for city population (natural log) and organization size, which approxi- mate the number of employees within the department. Form of government is a dummy variable indicating whether the gov- ernment is Mayor Council = 1 or Council-Manager = 0. The sample includes 27% of Mayor-Council cities. These data were collected from government websites and the U.S. Census. Finally, we include a variable measuring % of Internet use among city employees. Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for variables included in the model. Correlations among variables are reported in Appendix. Among benefits, the majority of managers agree or strongly agree that social media tools enhance the exchange of knowl- edge (62%) and useful information (55%), and that social media tools are helpful for their work (54%). Figure 3 shows public managers' overall perceptions of social media use as captured in the Positive Social Media Perception scale. The distribution of the variable shows that half of the managers in this study report a score between 3 and 3.84 out of 5-point Likert-type scale; overall, managers have a positive perception of social media tools (M= 3.33; Mon=3.29). To understand how individual and organizational use of social media, digital threats, technological capacity, and organi- zational culture shape perceptions of social media use among public managers, we conducted an ordinary least squares regres- sion model using R. The analysis of averaged Likert-type scales with parametric models is justified by the Central Limit Theorem, and previous studies have shown that parametric regression and data analysis models are robust when applied to Likert-type scales (Allen & Seaman, 2007; Norman, 2010). Table 2 shows the estimation results. The adjusted R indicates that 26% of the variance in the dependent variable is explained by the variables included in the model. Overall, there are significant variables in three out of five categories that we identified as important to explaining posi- tive social media perception: personal social media use (HI), organizational social media use (H2, H3), and organizational culture innovation (H8) and routineness (H10). Centralization (H9), digital threats (H4; H5), and technologi- cal capacity (H6; H7) are not significantly related to positive perceptions of social media use in the workplace. Thus, we find that individual and organizational determinants are sig. nificant in explaining social media perceptions among public managers, while technology-oriented factors are not Social media personal use is positively and significantly correlated with positive social media perception (B=0.151; p

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

1 Expert Approved Answer

Step: 1 Unlock

Question Has Been Solved by an Expert!

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts

Step: 2 Unlock

Step: 3 Unlock