Question: Decide if the speech adjustments below are about dialect or register differences. I say when I'm in Mexico, but when I'm in Argentina. I say

Decide if the speech adjustments below are about dialect or register differences.

- I say

when I'm in Mexico, but when I'm in Argentina. - I say

when my friends tell me an incredible story, but if a teacher tells it to me I say - The more time I spend in New York, the less I pronounce the syllable-final

in English. - When my friends ask me how I'm doing, I say , but when my boss asks me, I say .

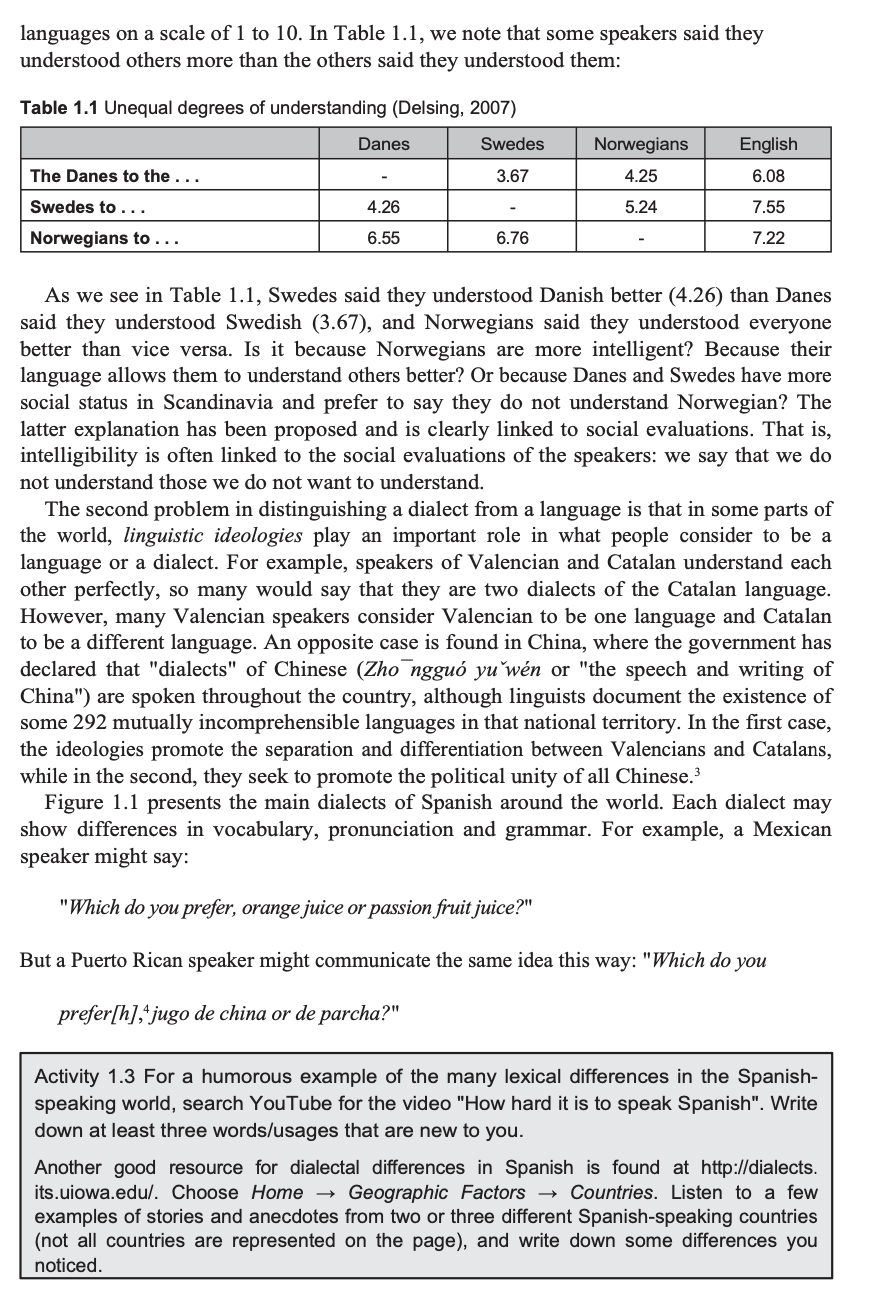

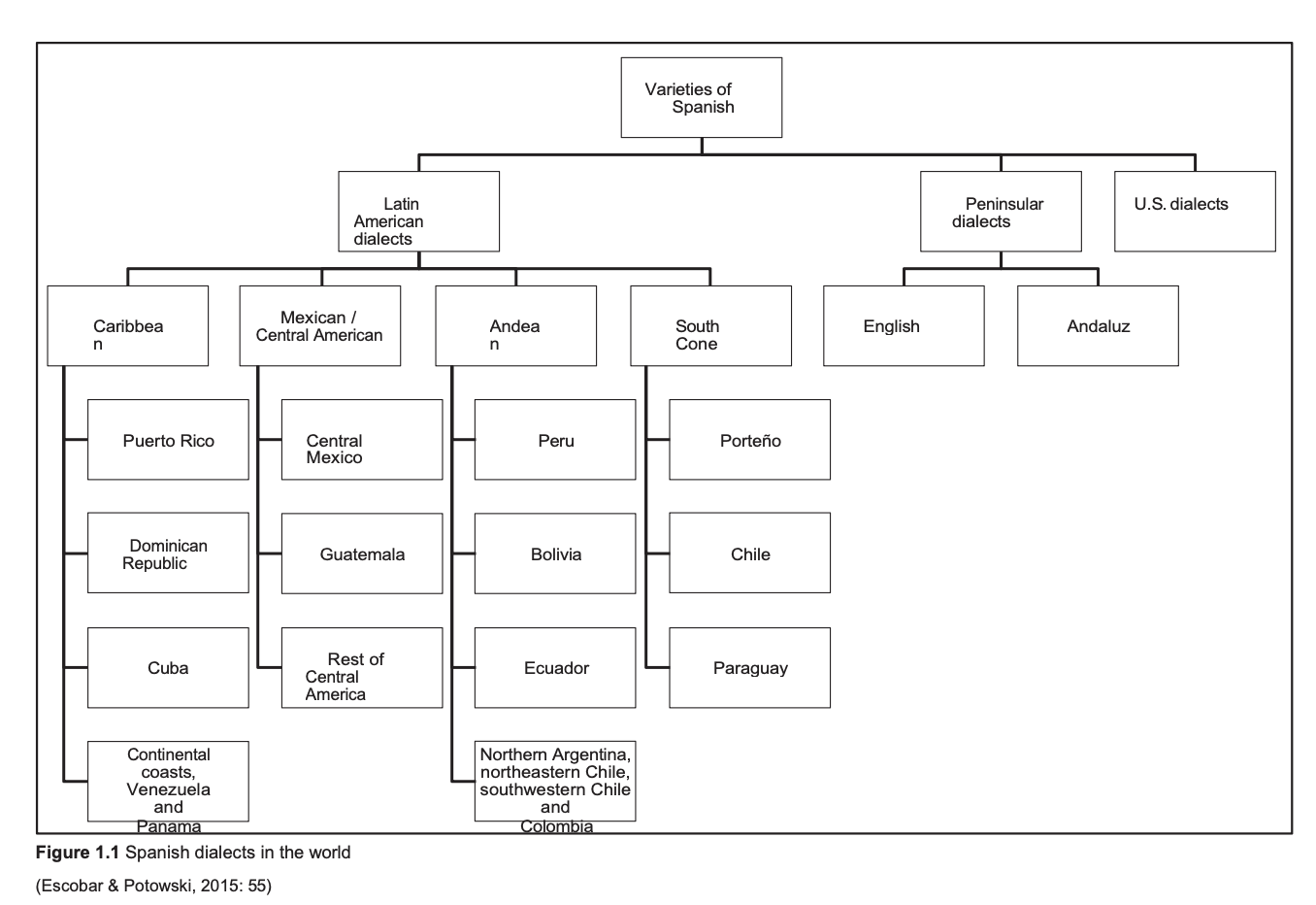

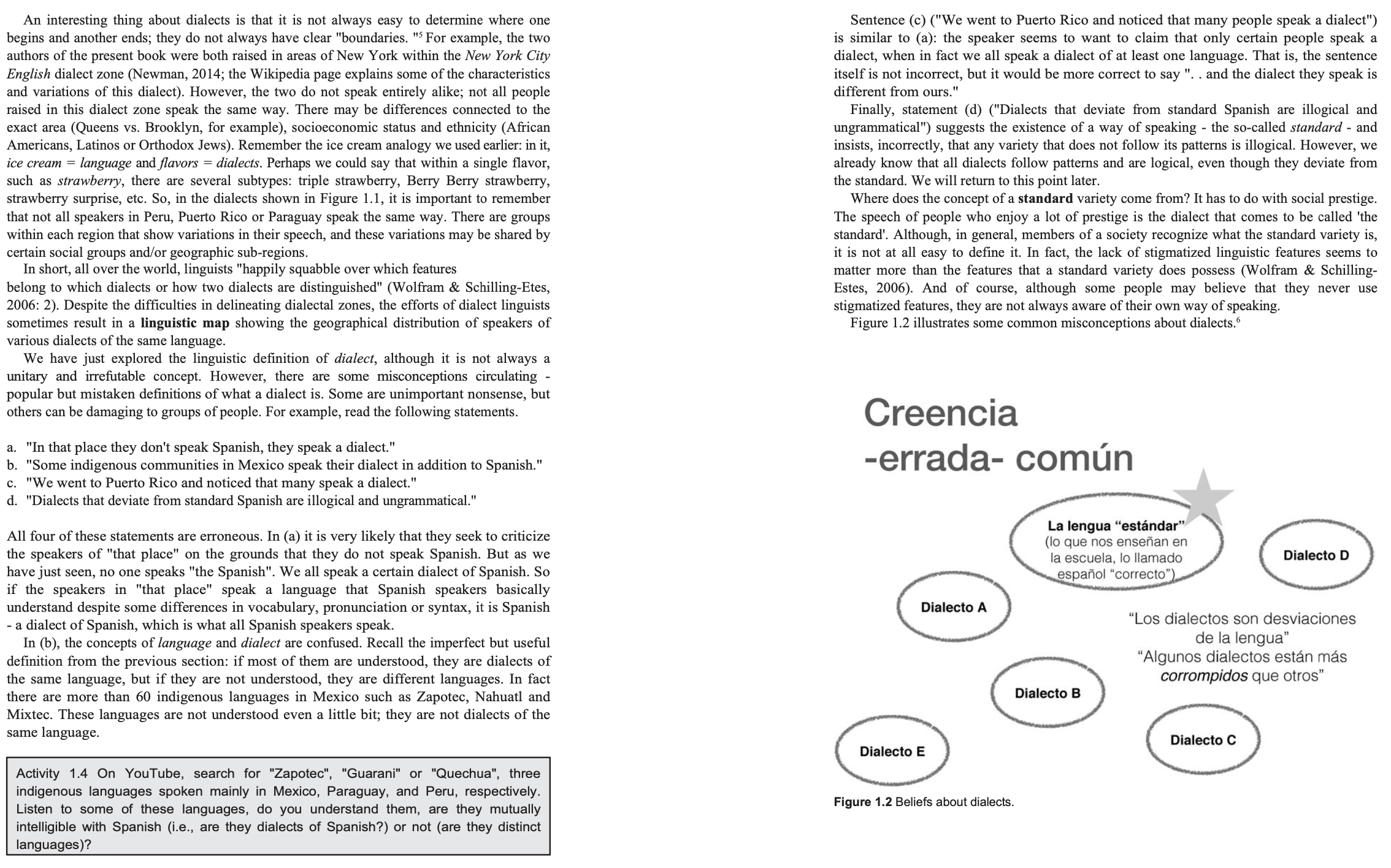

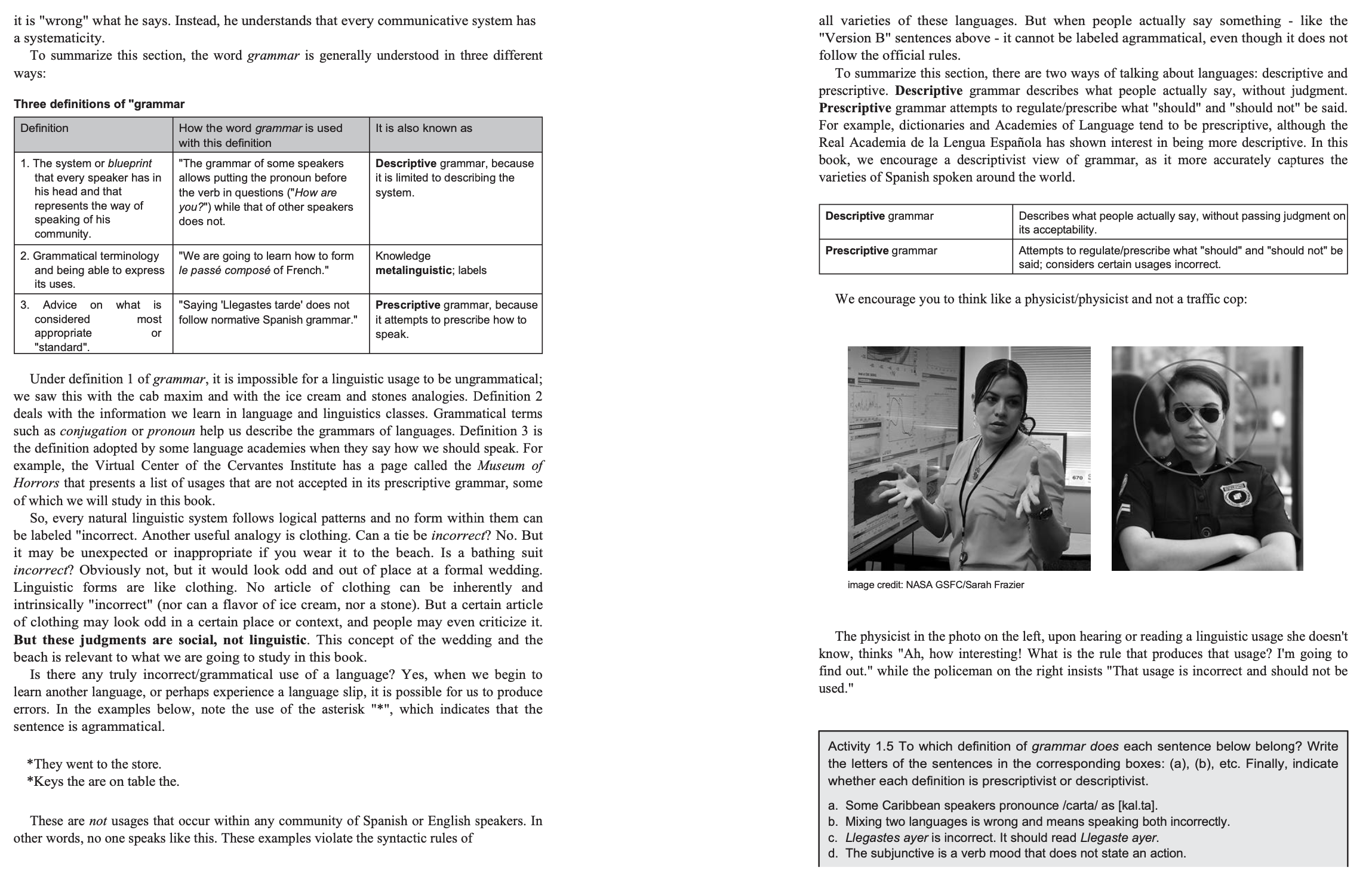

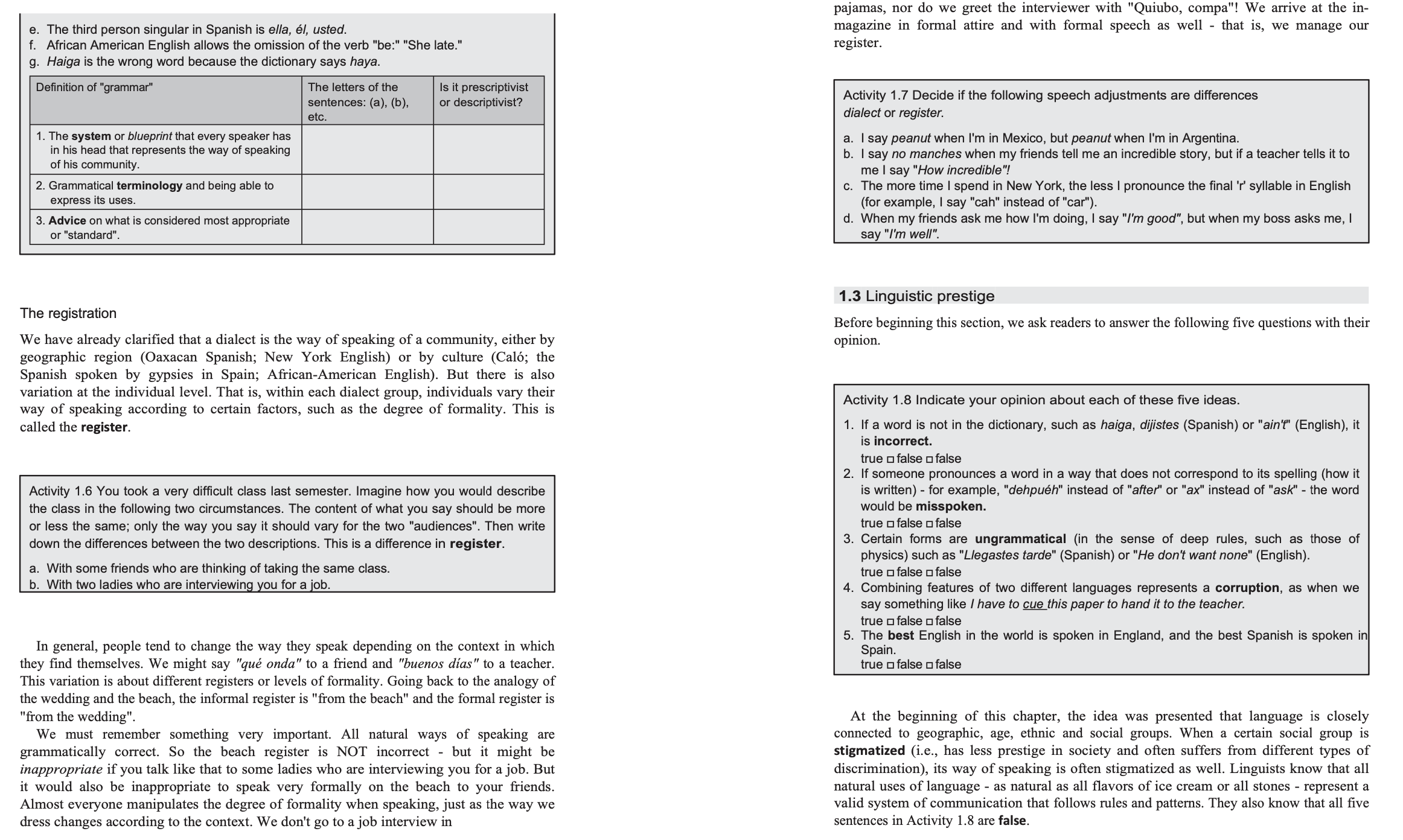

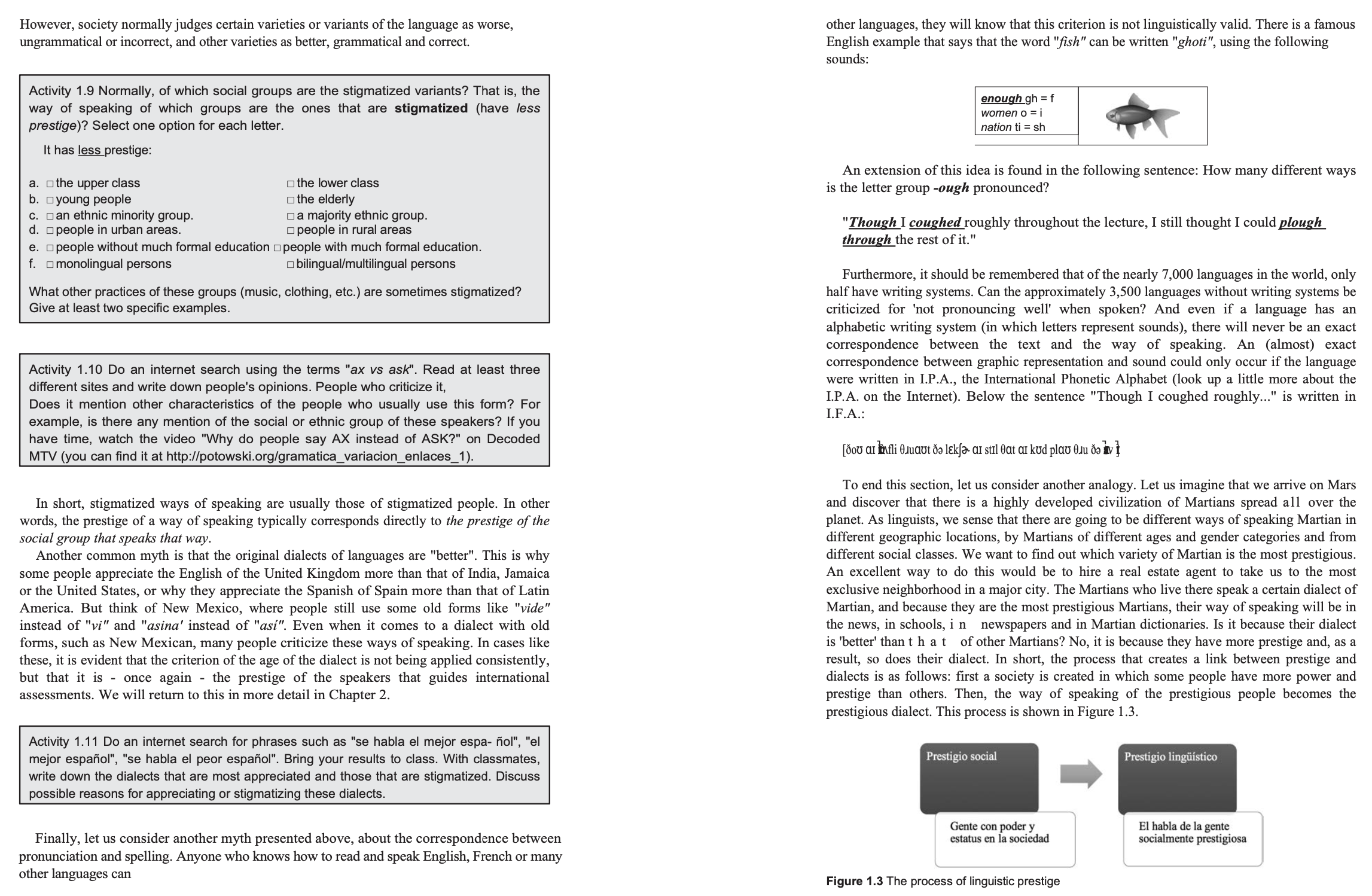

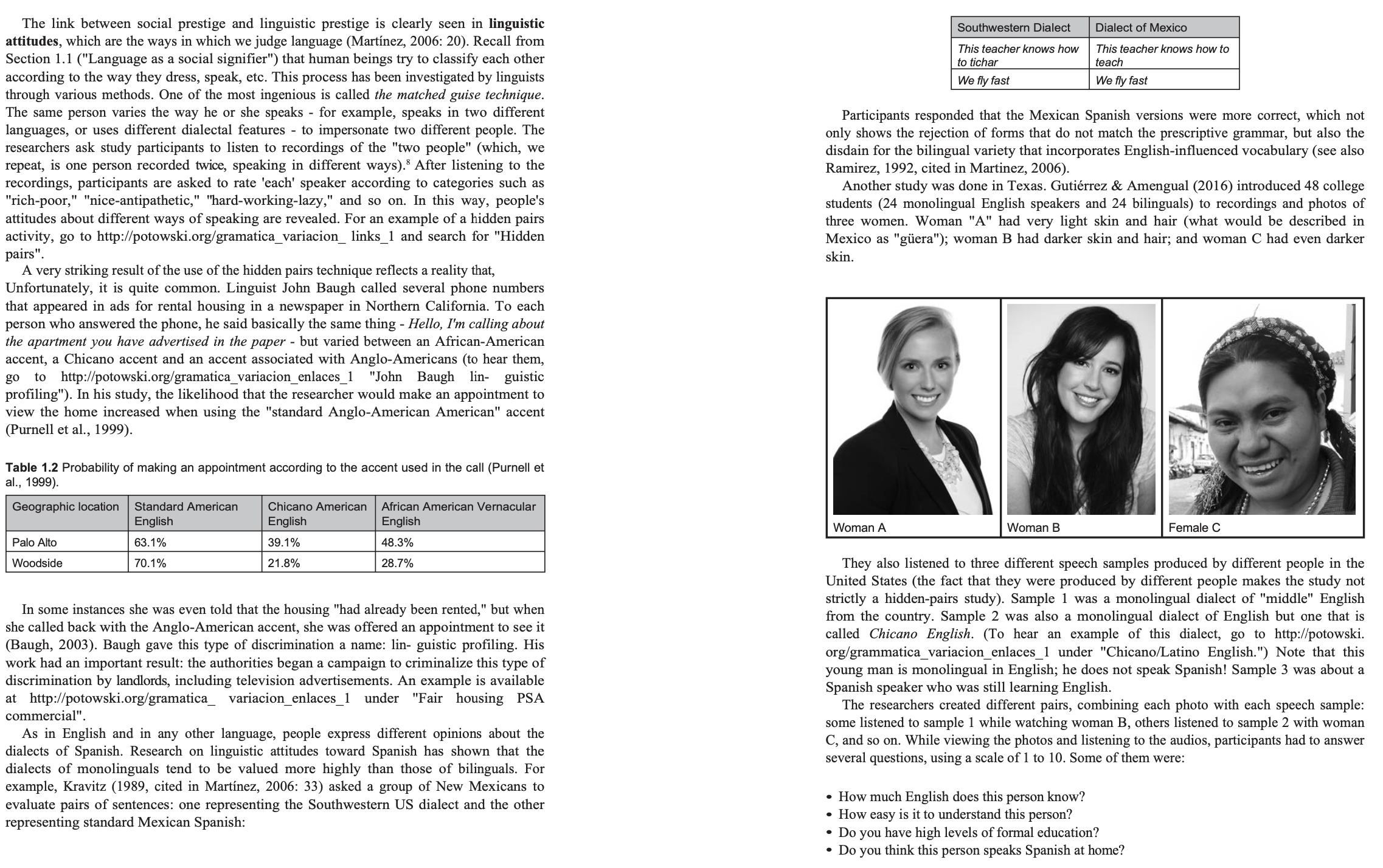

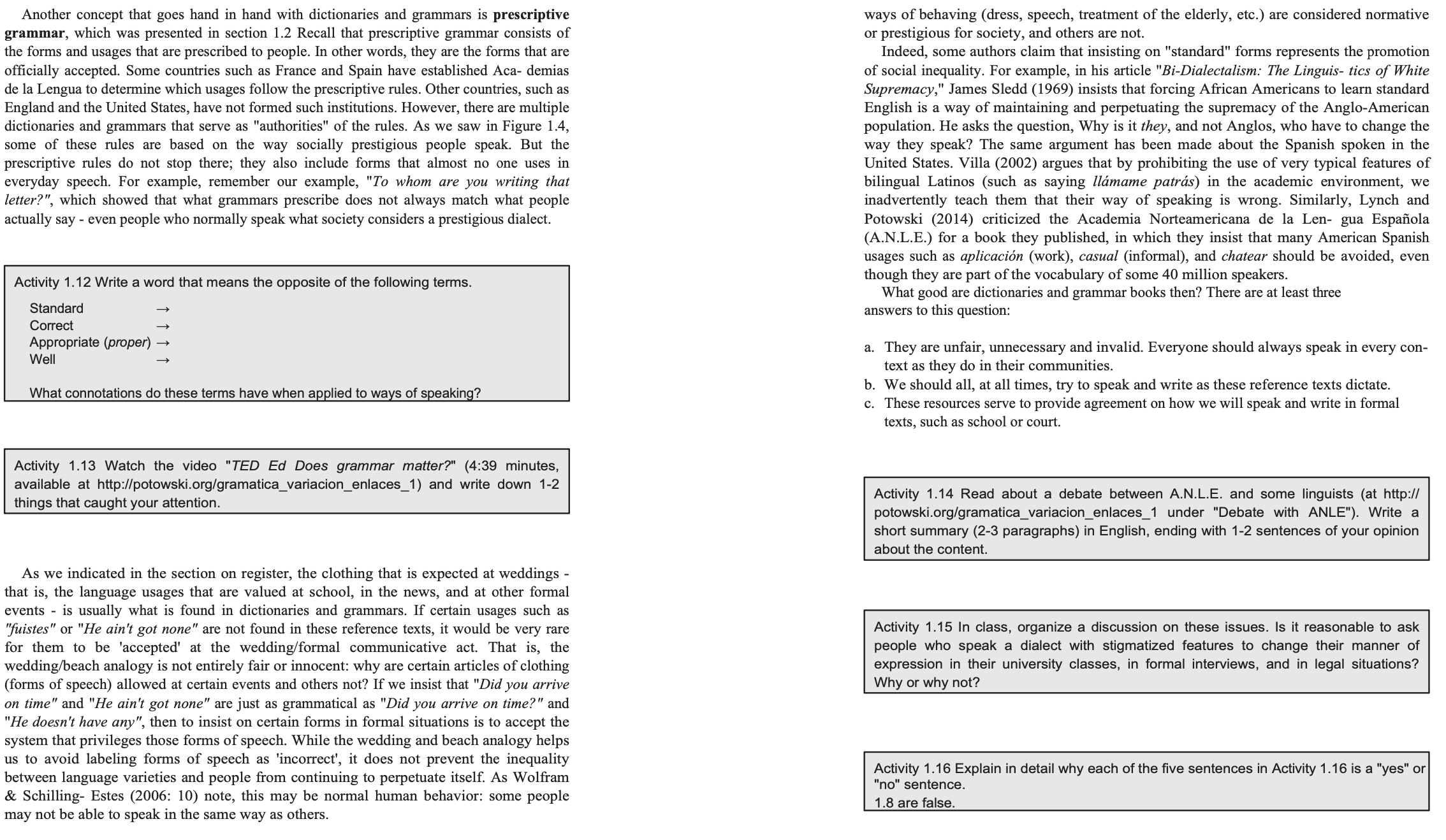

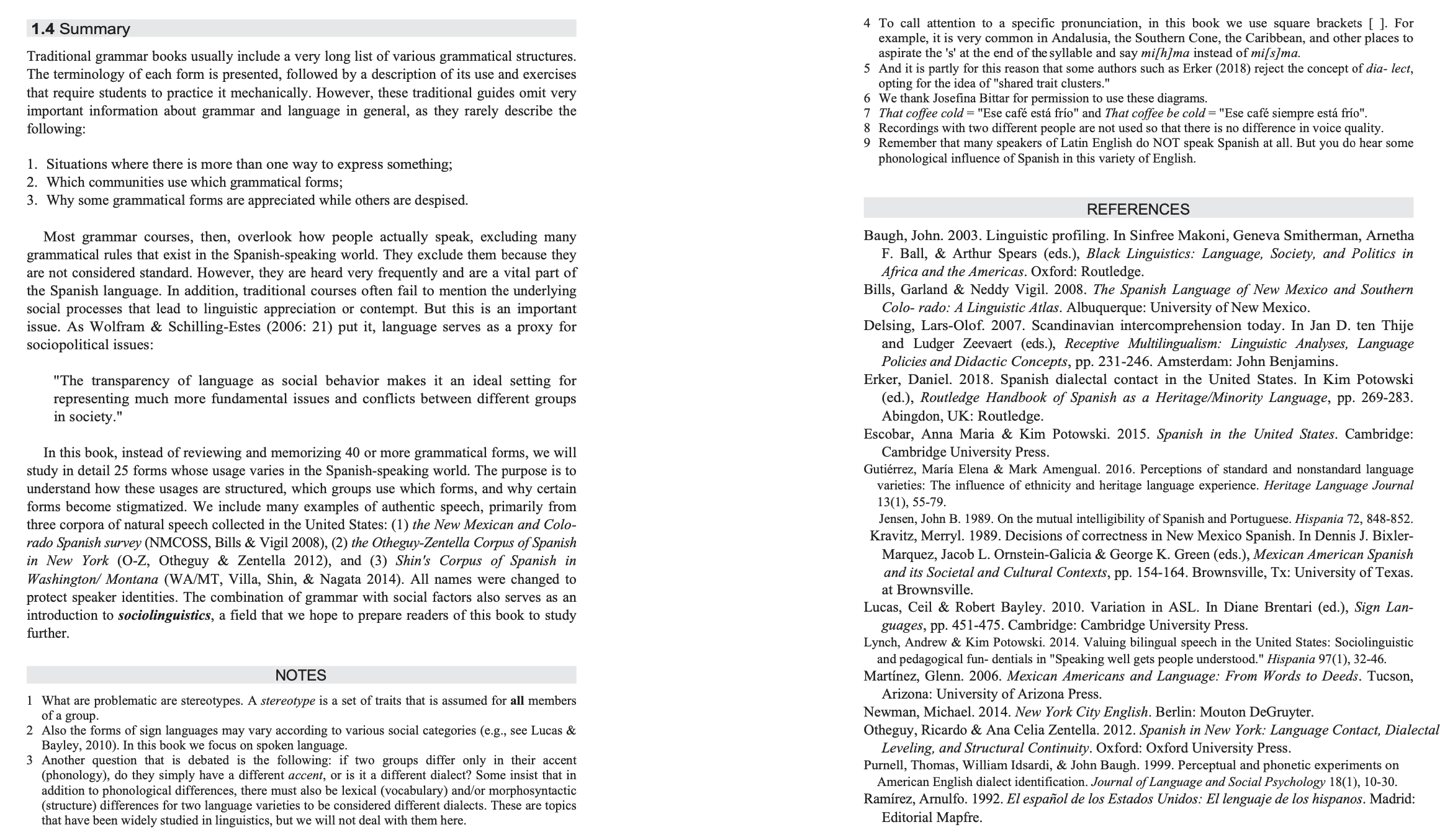

The main research question was: What influences participants' responses more: the voice or the photo? Here are some of the interesting results: 1. The more \"Spanish accent \"9 a sample had, the lower the attitudinal evaluations were in general, regardless of the photo. That is, the samples were evaluated as follows: 2. Overall, the Anglo accent sample was rated as the most understandable and proficient regardless of the photo - showing that the \"standard\" Anglo dialect is more appreciated than the Chicano dialect. Sample 3 (from the person who had English as a new language) was evaluated as the most difficult to understand - again, regardless of the photo. 3. The number of bilingual raters who said they could understand sample 3 was higher than among monolingual raters. 4. The photo influenced responses about whether the person used Spanish at home, but only among bilingual raters, who responded that the woman used Spanish at home more when sample 2 was paired with photo \\( \\mathrm{C} \\) than with photo \\( \\mathrm{A} \\). Although the photo did not affect the English evaluations of each sample, other studies indicate that physical traits rooted in a person's biology (the phenotype) can affect the evaluation of his or her speaking. In a famous study by Rubin (1992), 62 monolingual English language learners listened to a recording of a single 4-minute English lesson on a basic topic. The voice of the same woman, a native English speaker, was used for both recordings. While listening to the lesson, students viewed a picture of a woman who was supposed to represent the speaker. Half of the students were shown a picture of a Caucasian woman and half of the students were shown a picture of an Asian woman. Immediately after listening to the recording, students answered a series of questions about (1) the content and (2) the speaker's accent. Those who had seen the Asian face responded that the sample had a foreign accent. Remember that the same voice was used in both recordings, so it was a \"phantom accent\"! Even more surprising is the fact that, in the cases of the Asian woman's photo, the students answered more questions wrong, especially in the science lesson. These results suggest that ideologies influence ethnic and linguistic evaluations. Both Rubin (1992) and Gutierrez and Amengual (2016) found that presumed ethnicity influences how \"heard\" the way people speak. That is, sometimes people \"don't com- prehend\" certain people because they don't want to understand them. Why do some varieties have more prestige than others? Sometimes people answer that it is because of \"how it sounds\". Perhaps they say that they like the sounds of Italian better compared to German, or that American English sounds too 'nasal'. But consider the following example of the 'rr' sound. In Puerto Rico, instead of pronouncing the multiple \\( r \\) (as in carro or risa) in an alveolar manner - that is, in the front of the mouth - it is sometimes pronounced a velarized sound, that is, further back in the throat, so that carro sounds like caxo, and Ramn and jamn sound almost the same. Some Spanish speakers say they don't like Puerto Rican Spanish because they dislike this realization of 'rr'. But these same people could easily think that French is a very nice and prestigious language - even though French velarizes all the 'r's (so that franais sounds like fxanais). So, the perception of what sounds \"good\" or \"bad\" is influenced by certain prejudices. In the Spanish-speaking world, Puerto Ricans who say caxo instead of carro are not the most socially powerful people. If they were, people would most likely say that caxo sounds better than carro. Dictionaries, grammar books and academies of language What roles do dictionaries, grammar books and language academies play in the process of linguistic prestige? As we saw earlier with the Martians analogy, the words that make it into the dictionary and the forms of speech that make it into grammar books (also called \"grammars\") are those of favored groups. Again, their ways of speaking have no greater innate value, only greater social value. Language and power are inextricably linked. In this way, a self-maintaining cycle is created: The way of speaking of prestigious people enters the dictionary and the grammars; in turn, these people of the socioeconomic elite study in schools, institutions that resort to the aforementioned sources of reference to legitimize their way of speaking and exclude the ways of speaking of others. Figure 1.4 The cyuie u inuisul piesuye Language as a social signifier 1.1 Language as a social signifier 1.2 Dialects 1.3 Linguistic prestige 1.4 Summary 1.1 Language as a social signifier As soon as we see or hear new people, we almost unconsciously use various data to draw conclusions about them. For example, w e usually seek to classify them according to their gender, age, social class and ethnic group. We may also \"read\" something about their sexual orientation, their political leanings, or what part of the country they grew up in. What information do we use to infer all this information? There is visual data such as the way they dress, their hairstyle, tattoos, makeup and perhaps the way they walk and sit. Sometimes we get it wrong, especially if we rely on stereotypes. Stereotypes are different from schemas. Schemas are psychological structures that all human beings have to organize information. They help us process perceptions and incorporate new knowledge. For example, if we see a little girl in diapers who can barely walk, our schemas make us think that she will not know how to speak in complete sentences or solve algebra problems either. Another example would be listening to a man who seems to us to be Anglo-American but speaks fluent Mandarin. If we have had no previous experience with this type of individual - if our schemas have been formed only on the basis of people speaking Mandarin who seem to be from China - we might be surprised to find that this gentleman speaks this language. Far from being negative, schemas - underlying organizational patterns - are natural and necessary. \\( { }^{1} \\) To summarize, human beings try to \"classify\" everything we encounter around us according to the categories we have developed during our lives and in our communities. Activity 1.1 Using an internet search engine and the \"images\" function, search for these ten terms in English. 1. Truck driver 2. Restaurant server 3. Professor 4. Engineer 5. Nurse 6. Biker 7. Rapper 8. Police officer 9. Poker player. 10. Farmer Write down the characteristics of the people in most of the images you find: their gender, manner of dress, age, etc. Then, choose two (2) of the occupations and bring to However, society normally judges certain varieties or variants of the language as worse, ungrammatical or incorrect, and other varieties as better, grammatical and correct. Activity 1.10 Do an internet search using the terms \"ax vs ask\". Read at least three different sites and write down people's opinions. People who criticize it, Does it mention other characteristics of the people who usually use this form? For example, is there any mention of the social or ethnic group of these speakers? If you have time, watch the video \"Why do people say AX instead of ASK?\" on Decoded MTV (you can find it at http://potowski.org/gramatica_variacion_enlaces_1). In short, stigmatized ways of speaking are usually those of stigmatized people. In other words, the prestige of a way of speaking typically corresponds directly to the prestige of the social group that speaks that way. Another common myth is that the original dialects of languages are \"better\". This is why some people appreciate the English of the United Kingdom more than that of India, Jamaica or the United States, or why they appreciate the Spanish of Spain more than that of Latin America. But think of New Mexico, where people still use some old forms like \"vide\" instead of \"vi\" and \"asina' instead of \"asi\". Even when it comes to a dialect with old forms, such as New Mexican, many people criticize these ways of speaking. In cases like these, it is evident that the criterion of the age of the dialect is not being applied consistently, but that it is - once again - the prestige of the speakers that guides international assessments. We will return to this in more detail in Chapter 2. Activity 1.11 Do an internet search for phrases such as \"se habla el mejor espa- ol\", \"el mejor espaol\", \"se habla el peor espaol\". Bring your results to class. With classmates, write down the dialects that are most appreciated and those that are stigmatized. Discuss possible reasons for appreciating or stigmatizing these dialects. Finally, let us consider another myth presented above, about the correspondence between pronunciation and spelling. Anyone who knows how to read and speak English, French or many other languages can other languages, they will know that this criterion is not linguistically valid. There is a famous English example that says that the word \"fish\" can be written \"ghoti\", using the following sounds: An extension of this idea is found in the following sentence: How many different ways is the letter group -ough pronounced? \"Though I coughed roughly throughout the lecture, I still thought I could plough through the rest of it.\" Furthermore, it should be remembered that of the nearly 7,000 languages in the world, only half have writing systems. Can the approximately 3,500 languages without writing systems be criticized for 'not pronouncing well' when spoken? And even if a language has an alphabetic writing system (in which letters represent sounds), there will never be an exact correspondence between the text and the way of speaking. An (almost) exact correspondence between graphic representation and sound could only occur if the language were written in I.P.A., the International Phonetic Alphabet (look up a little more about the I.P.A. on the Internet). Below the sentence \"Though I coughed roughly...\" is written in I.F.A.: To end this section, let us consider another analogy. Let us imagine that we arrive on Mars and discover that there is a highly developed civilization of Martians spread all over the planet. As linguists, we sense that there are going to be different ways of speaking Martian in different geographic locations, by Martians of different ages and gender categories and from different social classes. We want to find out which variety of Martian is the most prestigious. An excellent way to do this would be to hire a real estate agent to take us to the most exclusive neighborhood in a major city. The Martians who live there speak a certain dialect of Martian, and because they are the most prestigious Martians, their way of speaking will be in the news, in schools, i n newspapers and in Martian dictionaries. Is it because their dialect is 'better' than \\( \\mathrm{t} \\mathrm{h} \\) a t of other Martians? No, it is because they have more prestige and, as a result, so does their dialect. In short, the process that creates a link between prestige and dialects is as follows: first a society is created in which some people have more power and prestige than others. Then, the way of speaking of the prestigious people becomes the prestigious dialect. This process is shown in Figure 1.3. Figure 1.3 The pivueso un minuisul piesulye Another concept that goes hand in hand with dictionaries and grammars is prescriptive grammar, which was presented in section 1.2 Recall that prescriptive grammar consists of the forms and usages that are prescribed to people. In other words, they are the forms that are officially accepted. Some countries such as France and Spain have established Aca- demias de la Lengua to determine which usages follow the prescriptive rules. Other countries, such as England and the United States, have not formed such institutions. However, there are multiple dictionaries and grammars that serve as \"authorities\" of the rules. As we saw in Figure 1.4, some of these rules are based on the way socially prestigious people speak. But the prescriptive rules do not stop there; they also include forms that almost no one uses in everyday speech. For example, remember our example, \"To whom are you writing that letter?\", which showed that what grammars prescribe does not always match what people actually say - even people who normally speak what society considers a prestigious dialect. Activity 1.12 Write a word that means the opposite of the following terms. \\( \\begin{array}{ll}\\text { Standard } & \ ightarrow \\\\ \\text { Correct } & \ ightarrow \\\\ \\text { Appropriate (proper) } & \ ightarrow \\\\ \\text { Well } & \ ightarrow\\end{array} \\) What connotations do these terms have when applied to ways of speaking? Activity 1.13 Watch the video \"TED Ed Does grammar matter?\" (4:39 minutes, available at http://potowski.org/gramatica_variacion_enlaces_1) and write down 1-2 things that caught your attention. As we indicated in the section on register, the clothing that is expected at weddings that is, the language usages that are valued at school, in the news, and at other formal events - is usually what is found in dictionaries and grammars. If certain usages such as \"fuistes\" or \"He ain't got none\" are not found in these reference texts, it would be very rare for them to be 'accepted' at the wedding/formal communicative act. That is, the wedding/beach analogy is not entirely fair or innocent: why are certain articles of clothing (forms of speech) allowed at certain events and others not? If we insist that \"Did you arrive on time\" and \"He ain't got none\" are just as grammatical as \"Did you arrive on time?\" and \"He doesn't have any\", then to insist on certain forms in formal situations is to accept the system that privileges those forms of speech. While the wedding and beach analogy helps us to avoid labeling forms of speech as 'incorrect', it does not prevent the inequality between language varieties and people from continuing to perpetuate itself. As Wolfram \\& Schilling- Estes (2006: 10) note, this may be normal human behavior: some people may not be able to speak in the same way as others. ways of behaving (dress, speech, treatment of the elderly, etc.) are considered normative or prestigious for society, and others are not. Indeed, some authors claim that insisting on \"standard\" forms represents the promotion of social inequality. For example, in his article \"Bi-Dialectalism: The Linguis- tics of White Supremacy,\" James Sledd (1969) insists that forcing African Americans to learn standard English is a way of maintaining and perpetuating the supremacy of the Anglo-American population. He asks the question, Why is it they, and not Anglos, who have to change the way they speak? The same argument has been made about the Spanish spoken in the United States. Villa (2002) argues that by prohibiting the use of very typical features of bilingual Latinos (such as saying llmame patrs) in the academic environment, we inadvertently teach them that their way of speaking is wrong. Similarly, Lynch and Potowski (2014) criticized the Academia Norteamericana de la Len- gua Espaola (A.N.L.E.) for a book they published, in which they insist that many American Spanish usages such as aplicacin (work), casual (informal), and chatear should be avoided, even though they are part of the vocabulary of some 40 million speakers. What good are dictionaries and grammar books then? There are at least three answers to this question: a. They are unfair, unnecessary and invalid. Everyone should always speak in every context as they do in their communities. b. We should all, at all times, try to speak and write as these reference texts dictate. c. These resources serve to provide agreement on how we will speak and write in formal texts, such as school or court. Activity 1.14 Read about a debate between A.N.L.E. and some linguists (at http:// potowski.org/gramatica_variacion_enlaces_1 under \"Debate with ANLE\"). Write a short summary (2-3 paragraphs) in English, ending with 1-2 sentences of your opinion about the content. Activity 1.15 In class, organize a discussion on these issues. Is it reasonable to ask people who speak a dialect with stigmatized features to change their manner of expression in their university classes, in formal interviews, and in legal situations? Why or why not? Activity 1.16 Explain in detail why each of the five sentences in Activity 1.16 is a \"yes\" or \"no\" sentence. 1.8 are false. it is \"wrong\" what he says. Instead, he understands that every communicative system has a systematicity. To summarize this section, the word grammar is generally understood in three different ways: Three definitions of \"arammar all varieties of these languages. But when people actually say something - like the \"Version B\" sentences above - it cannot be labeled agrammatical, even though it does not follow the official rules. To summarize this section, there are two ways of talking about languages: descriptive and prescriptive. Descriptive grammar describes what people actually say, without judgment. Prescriptive grammar attempts to regulate/prescribe what \"should\" and \"should not\" be said. For example, dictionaries and Academies of Language tend to be prescriptive, although the Real Academia de la Lengua Espaola has shown interest in being more descriptive. In this book, we encourage a descriptivist view of grammar, as it more accurately captures the varieties of Spanish spoken around the world. We encourage you to think like a physicist/physicist and not a traffic cop: The physicist in the photo on the left, upon hearing or reading a linguistic usage she doesn't know, thinks \"Ah, how interesting! What is the rule that produces that usage? I'm going to find out.\" while the policeman on the right insists \"That usage is incorrect and should not be used.\" Activity 1.5 To which definition of grammar does each sentence below belong? Write the letters of the sentences in the corresponding boxes: (a), (b), etc. Finally, indicate whether each definition is prescriptivist or descriptivist. a. Some Caribbean speakers pronounce /carta/ as [kal.ta]. b. Mixing two languages is wrong and means speaking both incorrectly. c. Llegastes ayer is incorrect. It should read Llegaste ayer. d. The subjunctive is a verb mood that does not state an action. languages on a scale of 1 to 10 . In Table 1.1 , we note that some speakers said they understood others more than the others said they understood them: Table 1.1 Unequal degrees of understanding (Delsing, 2007) As we see in Table 1.1, Swedes said they understood Danish better (4.26) than Danes said they understood Swedish (3.67), and Norwegians said they understood everyone better than vice versa. Is it because Norwegians are more intelligent? Because their language allows them to understand others better? Or because Danes and Swedes have more social status in Scandinavia and prefer to say they do not understand Norwegian? The latter explanation has been proposed and is clearly linked to social evaluations. That is, intelligibility is often linked to the social evaluations of the speakers: we say that we do not understand those we do not want to understand. The second problem in distinguishing a dialect from a language is that in some parts of the world, linguistic ideologies play an important role in what people consider to be a language or a dialect. For example, speakers of Valencian and Catalan understand each other perfectly, so many would say that they are two dialects of the Catalan language. However, many Valencian speakers consider Valencian to be one language and Catalan to be a different language. An opposite case is found in China, where the government has declared that \"dialects\" of Chinese (Zho nggu yuwn or \"the speech and writing of China\") are spoken throughout the country, although linguists document the existence of some 292 mutually incomprehensible languages in that national territory. In the first case, the ideologies promote the separation and differentiation between Valencians and Catalans, while in the second, they seek to promote the political unity of all Chinese. \\( { }^{3} \\) Figure 1.1 presents the main dialects of Spanish around the world. Each dialect may show differences in vocabulary, pronunciation and grammar. For example, a Mexican speaker might say: \"Which do you prefer, orange juice or passion fruit juice?\" But a Puerto Rican speaker might communicate the same idea this way: \"Which do you \\[ \\text { prefer[h], }{ }^{4} \\text { jugo de china or de parcha?\" } \\] Activity 1.3 For a humorous example of the many lexical differences in the Spanishspeaking world, search YouTube for the video \"How hard it is to speak Spanish\". Write down at least three words/usages that are new to you. Another good resource for dialectal differences in Spanish is found at http://dialects. its.uiowa.edu/. Choose Home \\( \ ightarrow \\) Geographic Factors \\( \ ightarrow \\) Countries. Listen to a few examples of stories and anecdotes from two or three different Spanish-speaking countries (not all countries are represented on the page), and write down some differences you noticed. e. The third person singular in Spanish is ella, l, usted. f. African American English allows the omission of the verb \"be:\" \"She late.\" g. Haiga is the wrong word because the dictionary says haya. The registration We have already clarified that a dialect is the way of speaking of a community, either by geographic region (Oaxacan Spanish; New York English) or by culture (Cal; the Spanish spoken by gypsies in Spain; African-American English). But there is also variation at the individual level. That is, within each dialect group, individuals vary their way of speaking according to certain factors, such as the degree of formality. This is called the register. Activity 1.6 You took a very difficult class last semester. Imagine how you would describe the class in the following two circumstances. The content of what you say should be more or less the same; only the way you say it should vary for the two \"audiences\". Then write down the differences between the two descriptions. This is a difference in register. a. With some friends who are thinking of taking the same class. b. With two ladies who are interviewing you for a job. In general, people tend to change the way they speak depending on the context in which they find themselves. We might say \"qu onda\" to a friend and \"buenos dias\" to a teacher. This variation is about different registers or levels of formality. Going back to the analogy of the wedding and the beach, the informal register is \"from the beach\" and the formal register is \"from the wedding\". We must remember something very important. All natural ways of speaking are grammatically correct. So the beach register is NOT incorrect - but it might be inappropriate if you talk like that to some ladies who are interviewing you for a job. But it would also be inappropriate to speak very formally on the beach to your friends. Almost everyone manipulates the degree of formality when speaking, just as the way we dress changes according to the context. We don't go to a job interview in pajamas, nor do we greet the interviewer with \"Quiubo, compa\"! We arrive at the inmagazine in formal attire and with formal speech as well - that is, we manage our register. Activity 1.7 Decide if the following speech adjustments are differences dialect or register. a. I say peanut when I'm in Mexico, but peanut when I'm in Argentina. b. I say no manches when my friends tell me an incredible story, but if a teacher tells it to me I say \"How incredible\"! c. The more time I spend in New York, the less I pronounce the final ' \\( r \\) ' syllable in English (for example, I say \"cah\" instead of \"car\"). d. When my friends ask me how I'm doing, I say \"I'm good\", but when my boss asks me, I say \"I'm well\". 1.3 Linguistic prestige Before beginning this section, we ask readers to answer the following five questions with their opinion. Activity 1.8 Indicate your opinion about each of these five ideas. 1. If a word is not in the dictionary, such as haiga, dijistes (Spanish) or \"ain't\" (English), it is incorrect. true \\( \\square \\) false \\( \\square \\) false 2. If someone pronounces a word in a way that does not correspond to its spelling (how it is written) - for example, \"dehpuh\" instead of \"after\" or \"ax\" instead of \"ask\" - the word would be misspoken. true \\( \\square \\) false \\( \\square \\) false 3. Certain forms are ungrammatical (in the sense of deep rules, such as those of physics) such as \"Llegastes tarde\" (Spanish) or \"He don't want none\" (English). true \\( \\square \\) false \\( \\square \\) false 4. Combining features of two different languages represents a corruption, as when we say something like I have to cue this paper to hand it to the teacher. true \\( \\square \\) false \\( a \\) false 5. The best English in the world is spoken in England, and the best Spanish is spoken in Spain. true \\( \\square \\) false \\( \\square \\) false At the beginning of this chapter, the idea was presented that language is closely connected to geographic, age, ethnic and social groups. When a certain social group is stigmatized (i.e., has less prestige in society and often suffers from different types of discrimination), its way of speaking is often stigmatized as well. Linguists know that all natural uses of language - as natural as all flavors of ice cream or all stones - represent a valid system of communication that follows rules and patterns. They also know that all five sentences in Activity 1.8 are false. class three (3) specific images for each (a total of 6 images) that are representative of what you found. What does this exercise teach us about the stereotypes that society has? Although physical elements go a long way in projecting aspects of our identity, one of the most powerful elements in classifying people is the way they speak. \\( { }^{2} \\) In fact, we may sometimes rely more on language than on any other factor. As is clear from the Citibank commercials, language plays a central role in social identity. We rely on language as a key variable in identifying gender, age, socioeconomic status and other factors. The way a person speaks is no coincidence. On the contrary, it is almost always closely linked to the place of origin and the ethnic, age and socioeconomic group to which he or she belongs. That is why our schemas expect a certain behavior from a person who speaks in a certain way, and vice versa: they expect a certain way of speaking from a person who behaves in a certain way. The term we have just used, \"form of speech\", is not very precise. We will see in the following section the terms used in the scientific field of linguistics. 1.2 Dialects For linguists, the term dialect is neutral, with neither positive nor negative connotations. It is used to refer to the way of speaking shared by a group of speakers. The group of speakers may live in a certain geographic area, or share a cultural identity based on ethnicity, religion, etc. From this perspective, there are no \"good\" or \"bad\" dialects, nor better or worse than others. Moreover, we all speak a certain dialect of a language. In fact, it can be said that languages do not exist except through their dialects. No one speaks \"English\" or \"Spanish\"; they speak a certain dialect of English (that of the United States, of London, of New York City, etc.) or of Spanish (that of Puerto Rico, of Buenos Aires, of southern Spain, etc.). One way to conceptualize this definition of dialect is to think of ice cream. Imagine you walk into a store that sells ice cream, and you say to the clerk, \"Please, I'd like some ice cream.\" What will the clerk serve you? What will the clerk serve you? Can he serve you anything? No, it can't do you any good because you haven't specified the flavor of ice cream you want. In this analogy, \"ice cream\" is like \"Spanish\" (the language). Ice cream does not exist except through its flavors, and Spanish does not exist except through its dialects. Now, it may be that you prefer strawberry ice cream but your friend prefers chocolate ice cream. But can you say that strawberry flavor is better than chocolate? Of course it is. no. All flavors have the same intrinsic value. But society often places a different value on different flavors. For example, chocolate ice cream may be associated with people with a low level of education and pistachio ice cream with people with a high level of education. We will return to this point throughout this book. We have just stated that languages \"do not exist\" and that there are only many dialects of each one. However, we can agree that the text you are reading right now is not written in the Chinese language, nor in the Hungarian language, but in the Spanish language. What is the difference, then, between a dialect and a language? A useful, but very imperfect, definition is the following. If two people can understand each other - despite differences in pronunciation, vocabulary or syntax - they are the same language. If they do not understand each other, they are two different languages. This parameter is known as mutual comprehension or mutual intelligibility between language varieties. For example, if the speakers in Caracas and those in Madrid understand each other, then what they speak are dialects of the same language (Spanish). But since these speakers do not understand those in Istanbul (who speak Turkish), then Turkish and Spanish are different languages. Ha rti a \"magyart,\" the \"tudja olvasni.\" If you did not understand the previous sentence, it is because you do not know the Hungarian language, which is a different language from Spanish. Why do we say that this distinction between language and dialect is imperfect? Several cases cast doubt on the usefulness of mutual understanding as a criterion. First, understanding between speakers is sometimes uneven. For example, Jensen (1989) found that the oral varieties of Latin American Spanish and Brazilian Portuguese are mutually intelligible at levels from \50 to \60, but Brazilians understand Spanish better than vice versa. In another example, in Northern Europe, Delsing (2007) conducted an experiment with speakers of various languages, asking them to indicate the degree to which they understood other languages. An interesting thing about dialects is that it is not always easy to determine where one begins and another ends; they do not always have clear \"boundaries. \" \\( { }^{5} \\) For example, the two authors of the present book were both raised in areas of New York within the New York City English dialect zone (Newman, 2014; the Wikipedia page explains some of the characteristics and variations of this dialect). However, the two do not speak entirely alike; not all people raised in this dialect zone speak the same way. There may be differences connected to the exact area (Queens vs. Brooklyn, for example), socioeconomic status and ethnicity (African Americans, Latinos or Orthodox Jews). Remember the ice cream analogy we used earlier: in it, ice cream = language and flavors \\( = \\) dialects. Perhaps we could say that within a single flavor, such as strawberry, there are several subtypes: triple strawberry, Berry Berry strawberry, strawberry surprise, etc. So, in the dialects shown in Figure 1.1, it is important to remember that not all speakers in Peru, Puerto Rico or Paraguay speak the same way. There are groups within each region that show variations in their speech, and these variations may be shared by certain social groups and/or geographic sub-regions. In short, all over the world, linguists \"happily squabble over which features belong to which dialects or how two dialects are distinguished\" (Wolfram \\& Schilling-Etes, 2006: 2). Despite the difficulties in delineating dialectal zones, the efforts of dialect linguists sometimes result in a linguistic map showing the geographical distribution of speakers of various dialects of the same language. We have just explored the linguistic definition of dialect, although it is not always a unitary and irrefutable concept. However, there are some misconceptions circulating popular but mistaken definitions of what a dialect is. Some are unimportant nonsense, but others can be damaging to groups of people. For example, read the following statements. a. \"In that place they don't speak Spanish, they speak a dialect.\" b. \"Some indigenous communities in Mexico speak their dialect in addition to Spanish.\" c. \"We went to Puerto Rico and noticed that many speak a dialect.\" d. \"Dialects that deviate from standard Spanish are illogical and ungrammatical.\" All four of these statements are erroneous. In (a) it is very likely that they seek to criticize the speakers of \"that place\" on the grounds that they do not speak Spanish. But as we have just seen, no one speaks \"the Spanish\". We all speak a certain dialect of Spanish. So if the speakers in \"that place\" speak a language that Spanish speakers basically understand despite some differences in vocabulary, pronunciation or syntax, it is Spanish - a dialect of Spanish, which is what all Spanish speakers speak. In (b), the concepts of language and dialect are confused. Recall the imperfect but useful definition from the previous section: if most of them are understood, they are dialects of the same language, but if they are not understood, they are different languages. In fact there are more than 60 indigenous languages in Mexico such as Zapotec, Nahuatl and Mixtec. These languages are not understood even a little bit; they are not dialects of the same language. Activity 1.4 On YouTube, search for \"Zapotec\", \"Guarani\" or \"Quechua\", three indigenous languages spoken mainly in Mexico, Paraguay, and Peru, respectively. Listen to some of these languages, do you understand them, are they mutually intelligible with Spanish (i.e., are they dialects of Spanish?) or not (are they distinct languages)? Sentence (c) (\"We went to Puerto Rico and noticed that many people speak a dialect\") is similar to (a): the speaker seems to want to claim that only certain people speak a dialect, when in fact we all speak a dialect of at least one language. That is, the sentence itself is not incorrect, but it would be more correct to say \". . and the dialect they speak is different from ours.\" Finally, statement (d) (\"Dialects that deviate from standard Spanish are illogical and ungrammatical\") suggests the existence of a way of speaking - the so-called standard - and insists, incorrectly, that any variety that does not follow its patterns is illogical. However, we already know that all dialects follow patterns and are logical, even though they deviate from the standard. We will return to this point later. Where does the concept of a standard variety come from? It has to do with social prestige. The speech of people who enjoy a lot of prestige is the dialect that comes to be called 'the standard'. Although, in general, members of a society recognize what the standard variety is, it is not at all easy to define it. In fact, the lack of stigmatized linguistic features seems to matter more than the features that a standard variety does possess (Wolfram \\& SchillingEstes, 2006). And of course, although some people may believe that they never use stigmatized features, they are not always aware of their own way of speaking. Figure 1.2 illustrates some common misconceptions about dialects. \\( { }^{6} \\) The link between social prestige and linguistic prestige is clearly seen in linguistic attitudes, which are the ways in which we judge language (Martnez, 2006: 20). Recall from Section 1.1 (\"Language as a social signifier\") that human beings try to classify each other according to the way they dress, speak, etc. This process has been investigated by linguists through various methods. One of the most ingenious is called the matched guise technique. The same person varies the way he or she speaks - for example, speaks in two different languages, or uses different dialectal features - to impersonate two different people. The researchers ask study participants to listen to recordings of the \"two people\" (which, we repeat, is one person recorded twice, speaking in different ways) \\( { }^{8} \\) After listening to the recordings, participants are asked to rate 'each' speaker according to categories such as \"rich-poor,\" \"nice-antipathetic,\" \"hard-working-lazy,\" and so on. In this way, people's attitudes about different ways of speaking are revealed. For an example of a hidden pairs activity, go to http://potowski.org/gramatica_variacion_links_1 and search for \"Hidden pairs\". A very striking result of the use of the hidden pairs technique reflects a reality that, Unfortunately, it is quite common. Linguist John Baugh called several phone numbers that appeared in ads for rental housing in a newspaper in Northern California. To each person who answered the phone, he said basically the same thing - Hello, I'm calling about the apartment you have advertised in the paper - but varied between an African-American accent, a Chicano accent and an accent associated with Anglo-Americans (to hear them, go to http://potowski.org/gramatica_variacion_enlaces_1 \"John Baugh lin- guistic profiling\"). In his study, the likelihood that the researcher would make an appointment to view the home increased when using the \"standard Anglo-American American\" accent (Purnell et al., 1999). Table 1.2 Probability of making an appointment according to the accent used in the call (Purnell et al., 1999). In some instances she was even told that the housing \"had already been rented,\" but when she called back with the Anglo-American accent, she was offered an appointment to see it (Baugh, 2003). Baugh gave this type of discrimination a name: lin- guistic profiling. His work had an important result: the authorities began a campaign to criminalize this type of discrimination by landlords, including television advertisements. An example is available at http://potowski.org/gramatica_ variacion_enlaces_1 under \"Fair housing PSA commercial\". As in English and in any other language, people express different opinions about the dialects of Spanish. Research on linguistic attitudes toward Spanish has shown that the dialects of monolinguals tend to be valued more highly than those of bilinguals. For example, Kravitz (1989, cited in Martnez, 2006: 33) asked a group of New Mexicans to evaluate pairs of sentences: one representing the Southwestern US dialect and the other representing standard Mexican Spanish: Participants responded that the Mexican Spanish versions were more correct, which not only shows the rejection of forms that do not match the prescriptive grammar, but also the disdain for the bilingual variety that incorporates English-influenced vocabulary (see also Ramirez, 1992, cited in Martinez, 2006). Another study was done in Texas. Gutirrez \\& Amengual (2016) introduced 48 college students (24 monolingual English speakers and 24 bilinguals) to recordings and photos of three women. Woman \"A\" had very light skin and hair (what would be described in Mexico as \"gera\"); woman B had darker skin and hair; and woman \\( \\mathrm{C} \\) had even darker skin. They also listened to three different speech samples produced by different people in the United States (the fact that they were produced by different people makes the study not strictly a hidden-pairs study). Sample 1 was a monolingual dialect of \"middle\" English from the country. Sample 2 was also a monolingual dialect of English but one that is called Chicano English. (To hear an example of this dialect, go to http://potowski. org/grammatica_variacion_enlaces_1 under \"Chicano/Latino English.\") Note that this young man is monolingual in English; he does not speak Spanish! Sample 3 was about a Spanish speaker who was still learning English. The researchers created different pairs, combining each photo with each speech sample: some listened to sample 1 while watching woman B, others listened to sample 2 with woman \\( \\mathrm{C} \\), and so on. While viewing the photos and listening to the audios, participants had to answer several questions, using a scale of 1 to 10 . Some of them were: - How much English does this person know? - How easy is it to understand this person? - Do you have high levels of formal education? - Do you think this person speaks Spanish at home? 1.4 Summary Traditional grammar books usually include a very long list of various grammatical structures. The terminology of each form is presented, followed by a description of its use and exercises that require students to practice it mechanically. However, these traditional guides omit very important information about grammar and language in general, as they rarely describe the following: 1. Situations where there is more than one way to express something; 2. Which communities use which grammatical forms; 3. Why some grammatical forms are appreciated while others are despised. Most grammar courses, then, overlook how people actually speak, excluding many grammatical rules that exist in the Spanish-speaking world. They exclude them because they are not considered standard. However, they are heard very frequently and are a vital part of the Spanish language. In addition, traditional courses often fail to mention the underlying social processes that lead to linguistic appreciation or contempt. But this is an important issue. As Wolfram \\& Schilling-Estes (2006: 21) put it, language serves as a proxy for sociopolitical issues: \"The transparency of language as social behavior makes it an ideal setting for representing much more fundamental issues and conflicts between different groups in society.\" In this book, instead of reviewing and memorizing 40 or more grammatical forms, we will study in detail 25 forms whose usage varies in the Spanish-speaking world. The purpose is to understand how these usages are structured, which groups use which forms, and why certain forms become stigmatized. We include many examples of authentic speech, primarily from three corpora of natural speech collected in the United States: (1) the New Mexican and Colorado Spanish survey (NMCOSS, Bills \\& Vigil 2008), (2) the Otheguy-Zentella Corpus of Spanish in New York (O-Z, Otheguy \\& Zentella 2012), and (3) Shin's Corpus of Spanish in Washington/ Montana (WA/MT, Villa, Shin, \\& Nagata 2014). All names were changed to protect speaker identities. The combination of grammar with social factors also serves as an introduction to sociolinguistics, a field that we hope to prepare readers of this book to study further. NOTES 1 What are problematic are stereotypes. A stereotype is a set of traits that is assumed for all members of a group. 2 Also the forms of sign languages may vary according to various social categories (e.g., see Lucas \\& Bayley, 2010). In this book we focus on spoken language. 3 Another question that is debated is the following: if two groups differ only in their accent (phonology), do they simply have a different accent, or is it a different dialect? Some insist that in addition to phonological differences, there must also be lexical (vocabulary) and/or morphosyntactic (structure) differences for two language varieties to be considered different dialects. These are topics that have been widely studied in linguistics, but we will not deal with them here. 4 To call attention to a specific pronunciation, in this book we use square brackets [ ]. For example, it is very common in Andalusia, the Southern Cone, the Caribbean, and other places to aspirate the 's' at the end of the syllable and say mi[h]ma instead of \\( \\mathrm{mi}[\\mathrm{s}] \\mathrm{ma} \\). 5 And it is partly for this reason that some authors such as Erker (2018) reject the concept of dia-lect, opting for the idea of \"shared trait clusters.\" 6 We thank Josefina Bittar for permission to use these diagrams. 7 That coffee cold = \"Ese caf est fro\" and That coffee be cold = \"Ese caf siempre est fro\". 8 Recordings with two different people are not used so that there is no difference in voice quality. 9 Remember that many speakers of Latin English do NOT speak Spanish at all. But you do hear some phonological influence of Spanish in this variety of English. REFERENCES Baugh, John. 2003. Linguistic profiling. In Sinfree Makoni, Geneva Smitherman, Arnetha F. Ball, \\& Arthur Spears (eds.), Black Linguistics: Language, Society, and Politics in Africa and the Americas. Oxford: Routledge. Bills, Garland \\& Neddy Vigil. 2008. The Spanish Language of New Mexico and Southern Colo- rado: A Linguistic Atlas. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico. Delsing, Lars-Olof. 2007. Scandinavian intercomprehension today. In Jan D. ten Thije and Ludger Zeevaert (eds.), Receptive Multilingualism: Linguistic Analyses, Language Policies and Didactic Concepts, pp. 231-246. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Erker, Daniel. 2018. Spanish dialectal contact in the United States. In Kim Potowski (ed.), Routledge Handbook of Spanish as a Heritage/Minority Language, pp. 269-283. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. Escobar, Anna Maria \\& Kim Potowski. 2015. Spanish in the United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Gutirrez, Mara Elena \\& Mark Amengual. 2016. Perceptions of standard and nonstandard language varieties: The influence of ethnicity and heritage language experience. Heritage Language Journal 13(1), 55-79. Jensen, John B. 1989. On the mutual intelligibility of Spanish and Portuguese. Hispania 72, 848-852. Kravitz, Merryl. 1989. Decisions of correctness in New Mexico Spanish. In Dennis J. BixlerMarquez, Jacob L. Ornstein-Galicia \\& George K. Green (eds.), Mexican American Spanish and its Societal and Cultural Contexts, pp. 154-164. Brownsville, Tx: University of Texas. at Brownsville. Lucas, Ceil \\& Robert Bayley. 2010. Variation in ASL. In Diane Brentari (ed.), Sign Languages, pp. 451-475. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Lynch, Andrew \\& Kim Potowski. 2014. Valuing bilingual speech in the United States: Sociolinguistic and pedagogical fun- dentials in \"Speaking well gets people understood.\" Hispania 97(1), 32-46. Martnez, Glenn. 2006. Mexican Americans and Language: From Words to Deeds. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press. Newman, Michael. 2014. New York City English. Berlin: Mouton DeGruyter. Otheguy, Ricardo \\& Ana Celia Zentella. 2012. Spanish in New York: Language Contact, Dialecta Leveling, and Structural Continuity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Purnell, Thomas, William Idsardi, \\& John Baugh. 1999. Perceptual and phonetic experiments on American English dialect identification. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 18(1), 10-30. Ramrez, Arnulfo. 1992. El espaol de los Estados Unidos: El lenguaje de los hispanos. Madrid: Editorial Mapfre. As es como funciona en the strawberry flavor patterns, nor the patterns of other flavors. It follows the patterns of chocolate with nuts. This also happens in every natural linguistic system: it follows its own realidad... logic. Here are some examples in Spanish and English. rigure 1.2 (Contnuea) As we have been emphasizing, we all speak a dialect of a language. But many people reserve the concept of \"dialect\" only for those who speak in a way that is different from their own, often suggesting that it is corrupted or incorrect. Why can it be harmful to refer to different ways of speaking as \"dialects\"? Because it is an attempt to take away the legitimacy of the way people speak - to say that their 'flavor' of ice cream is less valid. We will see some concrete results of this discrimination later. The grammaticality of all dialects It is important to recognize that all dialects/language systems are grammatical because they follow patterns. To understand this concept, the linguist Steven Pinker proposed the \\( c a b \\) maxim, which goes like this: Every cab in the world must necessarily obey the laws of physics. For example, all cabs are affected by the law of gravity; they cannot fly. This maxim applies to language in this way: Just like the laws of physics, there is a logic that everyone follows when they speak. All natural language follows internal patterns. It is impossible for a natural language to violate the laws of \"physics\" (linguistic), that is, not to follow a logic. However, unlike the law of gravity, there are other types of laws that cabs can violate. For example, a cab can violate the laws of New York City, where it is forbidden to turn right when a traffic light is red, or of the state of Michigan, or those of Massachusetts, or London, etc. These laws, of course, can be broken because they are not as profound as the laws of physics. When speaking a language, something similar happens: dictionaries and grammar books tell us that we have to speak in a certain way, prescribing how to speak and write. Do they prescribe how to speak and write. Does that mean we always speak that way? Of course not. Our way of speaking does not always follow the rules. However, just because we deviate from the rules described in dictionaries or grammar books doesn't mean that we don't follow a logic. When we communicate, we always follow the deeper laws, those of \"physics\", those of the logic of any human language. Going back to the ice cream analogy, can you say that the chocolate nut flavor is \"wrong\"? Obviously the idea is ridiculous. The only thing that could be said is that it does not follow According to some sources, all examples in column \"Version A\" are considered \"grammatically correct\" while those in \"Version B\" are not. However, all sentences in column \"Version B\" are natural usages of speaker communities and, therefore, it is impossible for them to be ungrammatical (i.e., it is impossible for them to violate \"the laws of physics\"). They follow their own rules different from those of other speaker communities. In fact, there is a difference between \"That coffee cold\" and \"That coffee be cold\" - they do not mean exactly the same thing, and speakers of African American English know when to use which. \\( { }^{7} \\) To extend the cab maxim analogy, we could say that Version A English utterances follow the laws of driving in the United States, while Version B English utterances follow the rules of England. How did you react to examples \\( 1,2,5,6,7 \\), and 8 ? Now that you understand that all these ways of speaking (\"different flavors of ice cream\") are natural usages and, therefore, 100\\% grammatical, what do you think of your initial reaction? Examples 3 and 4 in the list may surprise you. In U.S. English, many, many people say, \"Who are you writing that letter to\"? because the alternative, \"To whom are you writing that letter\"? sounds too stilted. These examples show that what grammars tell us does not always match what people actually say - even people who normally speak what society considers a prestigious dialect. As Wolfram and Schilling-Estes (2006: 10) point out: \"if we were to take a sample of the everyday speech of most people, we would find that almost no one speaks ... in the manner prescribed in grammar books.\" The same is true for Spanish. To invoke another analogy, we invite you to think like a geologist. When geologists find a stone somewhere, it would never occur to them to say, \"This stone is incorrect.\" It would be ridiculous because stones cannot be \"wrong\"! They can only belong to a certain part of the planet or another. The same goes for manners of speech. If you hear a person speak in the way he acquired his language in his place of origin, never think that (Escobar \\& Potowski, 2015: 55)

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts