Question: Read the case study Public sector management and reform: Cook Islands experience (Glassie, 2018) and answer the following question: 1. The case study says that:

Read the case study Public sector management and reform: Cook Islands experience (Glassie, 2018) and answer the following question:

1. The case study says that: The publics perception of the public sector continued to be poor due to reactive communication and a lack of effective public relations with communities concerning government policies and programmes. (p.213) --- Explain what is the issue here by linking it to aspect(s) of good governance. (6 points)

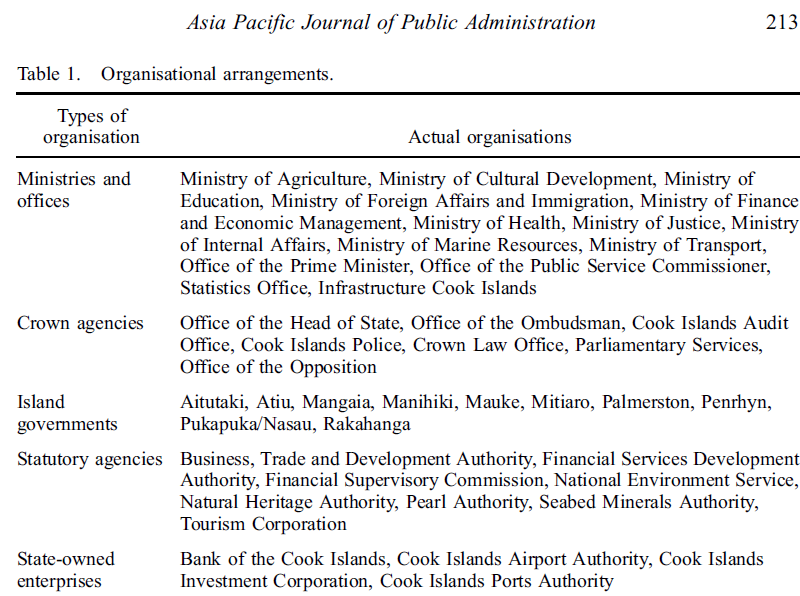

RESEARCH ARTICLE Public sector management and reform: Cook Islands experience Nandi T. Glassie Independent Researcher, House 55, Tipani Road, Nikao, Rarotonga, Cook Islands (Received 4 September 2018; accepted 19 October 2018) This article explores important features of the evolution of public sector management and reform in the Cook Islands, particularly from the mid-1990s. It addresses significant developments and challenges which require sound ongoing attention. In doing so, it contributes to an understanding of why and how small island developing states need to embrace programmes of public sector reform as a core component of their socio-economic development. Keywords: public sector management; public sector reform; performance manage- ment; devolution; small island states; Cook Islands Introduction The Cook Islands comprises fifteen small volcanic islands and atolls scattered over 1.8 million square kilometres of the Pacific Ocean and has a population of less than 18,000 people, of whom almost 70% live on the main island of Rarotonga as the centre of government and commerce (Statistics Office, 2012, 2017). The country occupies a total land area of 240 square kilometres in the centre of Polynesian, with Fiji Islands to the west, Tahiti to the east, Hawaii to the north, and New Zealand to the south. It is divided into the northern group as mostly atolls, and the southern group as mainly volcanic and raised atoll islands. The vast distances between these small islands present ongoing transportation and communication challenges. Since 1901, the Cook Islands has had a special constitutional relationship with New Zealand - which, since 1964, has involved its being internally self-governing in free association with New Zealand. The Constitution (1964) provides for a parliament within the realm of New Zealand, with Queen Elizabeth as the head of state represented by a local governor-general. The parliament comprises 24 elected members: 10 from Rarotonga and 14 from the other islands. A six-member cabinet is presided over by the prime minister. Management structures, reform and challenges Organisational arrangements As set out in Table 1, there are 14 ministries and offices, seven crown agencies, ten island governments, eight statutory agencies, and four state-owned enterprises. The first three groups of organisations comprise the public service as prescribed by the Public Service Act (2009). The other two groups are considered to be state services with degrees of autonomy from political control and accountability. Corresponding author. Email: glassienandi@gmail.com 2018 The University of Hong Kong Asia Pacific Journal of Public Administration 213 Table 1. Organisational arrangements. Types of organisation Actual organisations Ministries and Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Cultural Development, Ministry of offices Education, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Immigration, Ministry of Finance and Economic Management, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Internal Affairs, Ministry of Marine Resources, Ministry of Transport, Office of the Prime Minister, Office of the Public Service Commissioner, Statistics Office, Infrastructure Cook Islands Crown agencies Office of the Head of State, Office of the Ombudsman, Cook Islands Audit Office, Cook Islands Police, Crown Law Office, Parliamentary Services, Office of the Opposition Island Aitutaki, Atiu, Mangaia, Manihiki, Mauke, Mitiaro, Palmerston, Penrhyn, governments Pukapuka/Nasau, Rakahanga Statutory agencies Business, Trade and Development Authority, Financial Services Development Authority, Financial Supervisory Commission, National Environment Service, Natural Heritage Authority, Pearl Authority, Seabed Minerals Authority, Tourism Corporation State-owned Bank of the Cook Islands, Cook Islands Airport Authority, Cook Islands enterprises Investment Corporation, Cook Islands Ports Authority These relatively complex organisational arrangements make it difficult for the public, and even public servants, to fully understand how the system of government works, how it is paid for, and how it is made accountable. All of the organisations involved require plans, budgets, performance reviews and audits. The volume of work entailed in compiling the information and meeting the requirements individually and across the system inevitably results in inefficiencies, quality issues, delays in the preparation and auditing of financial statements, and associated delays in the reporting to parliament. The duplication of functions leads to an inefficient use of limited resources. Over 300 corporate support roles in financial management and administration account for $8million annually, which is almost 15% of the personnel budget (Public Sector Strategy 2016-2025, 2016, p. 10). Reporting lines are not sufficiently clear or logical and performance management is not well-developed and con- sistent throughout the system, resulting in problems of control and accountability. Reform programme and developments An analysis by the Asian Development Bank (2002) highlighted the extent to which the Cook Islands, especially in 19951996, was facing a national financial crisis. There were threats to the economy through labour force decline resulting from continual emigration; poor balance of payments through over-reliance on tourism; poor infrastructure particu- larly in the outer islands due to weak policy, planning and project preparation mechan- isms; and high levels of external debt. Years of economic mismanagement and imprudent policy responses had contributed significantly to the economic setbacks, which were compounded by a reduction in international air services, the outbreak of dengue fever mainly on Rarotonga, and the restoration of nuclear testing at Mururoa in neighbouring Tahiti. All of these factors resulted in declining economic opportunities, particularly in the tourism sector. 214 N. T. Glassie The adopted reform programme, which was aimed at economic recovery, included shifting from a public sector driven economy to a private sector led economy focused on development and sustainability. The programme emphasised five key points: right sizing the public sector; privatising those government functions and agencies that would operate better in the private sector than in the public sector; providing incentives for private sector growth; curbing government spending and increasing revenue collection; and rescheduling the time frame for repaying local and international debts (Wichman, 2008). The public service had long been perceived as over-staffed, with officials not perform- ing to expected standards. It was not unusual to observe a group of two or three people performing a job that could have been undertaken by one person. Standard work perfor- mance procedures for officials required attention. Action was essential concerning most aspects of public sector management on the grounds that the over-staffed public sector had aspects of public sector management on the grounds that the over-staffed public sector had increased national debt and aid-funded programmes and, in the process, had constrained the growth of the private sector as the productive base of the economy. Associated measures were necessary to improve access to land and capital and to improve policy and regulatory instruments for overseas and local investors (Wichman, 2008). Over the last decade, several legislative initiatives have been taken to enhance public sector efficiency and responsiveness. These have included the introduction of the Public Service Act (2009) to streamline the administration and regulation of the public service; the Employment Relations Act (2012) to establish good employment relations between employers and employees; the Island Government Act (2012-13) to foster good govern- ance by island governments, and the Official Information Act (2008) to provide the public with a legal right of access to government information. In terms of plans and strategies, the National Sustainable Development Plan 2011- 2015 (2011) set out national goals across priority areas. The plan was comprehensive and ambitious, but did not include a monitoring, evaluation and results framework as a critical basis for improving economic and administrative performance. Accordingly, government policy priorities remained unclear and were unable to be assessed as mean- ingfully as they needed to be. The public's perception of the public sector continued to be poor due to reactive communication and a lack of effective public relations with com- munities concerning government policies and programmes. Recently, two key documents have been published: the Public Sector Strategy 2016- 2025 (2016) and the annual report of the Public Service Commissioner (2017). According to the Public Service Commissioner (2017), the biggest challenge facing the public service is the shifting of mindsets and organisational cultures to a more strategic outcomes focus, with planning, actions and budgets to achieve these outcomes. The 2025 (2016) and the annual report of the Public Service Commissioner (2017). According to the Public Service Commissioner (2017), the biggest challenge facing the public service is the shifting of mindsets and organisational cultures to a more strategic outcomes focus, with planning, actions and budgets to achieve these outcomes. The Public Service Commissioner (2017) and the Public Sector Strategy 2016-2025 (2016) alike appreciate that a "public service of excellence requires effective leadership and team-work in seeking to strengthen efficient and effective capacity building, planning and performance across the public sector. The focus of the Public Service Commissioner (2017) is on lifting the strategic planning and reporting capability of public service organisations; supporting workforce development, strengthening organisational management practices; conducting organisa- tional capacity assessments; promoting leadership, talent and graduate recruitment pro- grammes; ensuring the continuation of public service induction training; and clarifying the roles, responsibilities and accountability of state service organisations. These are all matters in need of ongoing attention as means of facilitating increased administrative capacity, service delivery and accountability. They are realistic and able to be achieved, Asia Pacific Journal of Public Administration 215 subject especially to the extent that there are sufficient resources, commitment and action to sustain them in the longer term in accordance with national goals and commitments. Specific initiatives to-date have concerned key areas of the Public Sector Strategy 2016- 2025 (2016): people, structures and systems. A comprehensive HRM policy framework has been introduced, along with a performance management system, remuneration system, and recruitment practices to attract the best people into roles. Training programmes have been introduced to address the mindset changes needed across the public service from one of completing activities to that of producing outputs linked to better outcomes. The public service induction programme - which embeds an understanding of the role of public servants, of how the machinery of government operates, of significant HRM policies, and of the integrity and conduct expectations of public servants - has been completed by over 1,100 officials. A leadership and management training course has sought to improve the management capacity of senior public servants, and post-graduate courses have been provided to public servants as potential leaders for the future. A 40-person HR taskforce has been established and trained in preparing job descriptions and job evaluations and in using support systems in the development and maintenance of relevant HRM policies and practices for the public service. In addition, the government remuneration system has been aligned to the pay structure and career pathways for all roles across the public service. This alignment is complemented by a performance management system which seeks to reward exemplary performance and provide support where performance improvement is required. Also, an organisational performance improvement framework has been put in place to measure the delivery of outputs and results and to provide a basis for strengthening organisational infrastructure. Initial indications are that two of the ministries are performing above expectations and five are meeting expectations (Public Service Commissioner, 2017). With regard to island governments, changes had been made in the late 1990s in response to elements of the financial crisis which were deemed to require the territorial devolution of administrative functions and power. The aim had been to shift responsi- bility for as many government services as possible to the governments of the outer islands in the hope of increasing administrative responsiveness and public access to services. But little thought was given to crucial matters of whether or not the island governments were prepared for the new challenges involved and, more specifically, whether or not they had the capacity to manage their financial, human and infrastructural resources without relying on the central administration in Rarotonga. The consequence was that several of the devolved functions were soon re-centralised, including those involving aspects of education, health, police and justice, with largely only agriculture and infrastructure remaining as immediate island responsibilities. Subsequently, devolution policy guidelines were developed on the basis of national and outer island consultations. The guidelines addressed components of the devolution programme relating to legal, financial and administrative requirements. Somewhat belat- edly, they also focused on the upgrading of the skills needed to manage the financial and development aspects of devolution. The legislation required to complete the devolution process went through 13 drafts, with 19 versions having been prepared. Eventually, after many debates and delays, it was passed as the Island Government Act (2012-13). T1 ilond that +1 onda 20 1 The essence of the island governments is that the islands are each governed by a council comprising an elected mayor, elected island councillors, and elected represen- tatives from each village. Local policies are expected to be discussed and agreed at the council level before plans of action are handed to the island administration for 216 N. T. Glassie implementation under the supervision of a council executive officer (EO). The EO is in charge of the island administration and reports to the council through the mayor. Politically-appointed government representatives act as the government's eyes and ears on the island and report developments directly to the Office of the Prime Minister. Personal insights while working as the chief executive of the Office of the Minister of Island Administration between 2001 and 2006 provide a basis on which to comment on island governments prior to the enactment of the Island Government Act (2012-13). The Act has fostered some improvements in the operating procedures and in the lines of control and accountability of island governments. At the same time, several problems remain and need continually to be addressed. There have been various conflicts on the islands and between the island govrenments and the central administration. On several of the islands, conflicts have occurred between the mayors and island secretaries (now EOs). In one case, a mayor removed from office successive secretaries for insubordination, with the justifications sometimes being more personal than official. On one island, tense arguments between the mayor and the island secretary almost resulted in physical violence. At times, central intervention has been necessary, such as when the mayor of Mangaia instructed the closure of the Mangaia airport for fear of a dengue fever outbreak from incoming flights. Under instruction from the Minister of Police, a team of armed police was despatched by patrol boat to Mangaia during the night. By next morning, the airport had been cleared and re-opened by police for regular flights. In another case, the mayor of Penrhyn threatened to shoot a pearl farmer for allowing her workers to work in clear breach of the Sunday work taboo. Again under instruction from the Minister of Police, an armed squad was sent on a four-hour flight to the northern atoll to contain the situation. Questions have arisen concerning whether the government in Rarotonga has been fully aware of devolutionary principles and how to implement such a programme. Have the people of the islands been prepared for devolution, and have they understood the concept of devolution? Have government employees been prepared to face up to job losses at the centre as a result of the developments? Have successive governments been aware of the negative impact on the ground of residents leaving their home islands for Rarotonga, and continuing on to New Zealand and Australia? While these and related questions were particularly relevant to before the Island Government Act (2012-13) was introduced, they remain important. Significant challenges Technological advances reduce the number of administrative positions required, but also increase the knowledge, skills and experience requirements for positions in governance, policy, regulation, corporate support, and service delivery. Leadership and management skills are critical to the ability of organisations to fulfil their functions adequately; yet many senior positions are held by people without these skills. Financial constraints, poor workforce planning, inconsistencies in performance management, a lack of focus on capability development, and poor recruitment practices and systems are among the many issues that negatively affect the country's ability to attract and retain high performing employees. For some positions it is impossible to find suitable candidates from within the local population; accordingly, organisations either appoint people without the skills for the roles, or fill positions with technical specialists from overseas on short or long term bases, often using donor funding. Such recruitment experience, which involves the Asia Pacific Journal of Public Administration 217 challenge of matching skilled people with what it takes to do the work, is a significant reason why many organisations do not meet performance expectations. The Labour Market Remuneration Survey (2015) reports that 85% of employers identified a link between performance and salary; but, without an updated remuneration framework and an across-the-service capability development and performance manage- ment system that is consistently applied, the public sector does not have the mechanisms in place to attract and retain high performers. A third of public sector employees are under the age of 40; 42% are aged 40 to 59; and 11% are aged 60 or over (Public Sector Strategy 2016-2025, 2016, p. 8). There is very little succession planning or capability development occurring to ensure a flow of talent through public sector career pathways to fill positions, including those that become vacant as a result of retirement. The public sector employs 2,200 full time equivalent people, which represents 16.9% of the population. The total personnel budget for 20152016 was $55million, which was more than twice the budget for 20002001. Employees aged 60 or older account for $6.7million in salary and pension contributions, representing around 12% of total personnel costs (Public Sector Strategy 2016-2025, 2016, p. 8). The annual salary of most island government employees is between $10,000 and $15,000 (approximately $6.25 per hour). Just under 1,000 employees are paid an annual salary of between $16,000 and $39,999. Nine employees are paid an annual salary of $100,000 or more (Public Sector Strategy 2016-2025, 2016, p. 8). These personnel costs pose enormous challenges for the government and the econ- omy. They make it all the more important that there be highly effective productivity and performance management systems in place, along with sector-wide plans for developing leadership and management capability and for training officials in all aspects of their work. Such initiatives are essential to help officials learn how to solve systemic pro- blems, particularly with service delivery, and to improve performance in other ways through better planning, budgeting, monitoring and evaluation, policy development, and policy implementation. Across the public service, poor service delivery is still evident and members of the public experience frustration in delayed service waiting times. These service problems and the challenges inherent in them are accompanied by tourism growth having placed pressure on water and sanitation infrastructure, as well as other aspects of the environ- ment. Accordingly, more investment is urgently need in capital infrastructure. While the budget has continued to increase with steady GDP growth over the last decade, the public service continues to claim under-resourcing, particularly in the areas of infrastructure (capital projects and maintenance), justice (judiciary, land matters and the prison), health (rising prevalence of non-communicable diseases), and law, order and governance (Crown Law, Police, Ombudsman and central agencies). These are all areas for which significant funding will always be required. An assessment by Tisam (2015) is that public management reform has assisted in the improvement of economic performance and facilitated the growth in the private sector, including through fostering a shift in employment from government to the private sector, notably in tourism and related industries. But there have also been negative outcomes which pose an array of challenges. Included are an increase in out-migration; incidences of corruption in the procurement and awarding of contracts; increase in the cost of living partly as a result of the rise of government monopolies and a private sector oligopoly which determines price markets; imbalance in developments in the outer islands, and WHICHI UCITICS PTICE Thai Kets, moalance vclopTICTS III thic outci ISTATUS, and inequality in income distribution leading to outward migration. 218 N. T. Glassie Concluding comments Public sector reform takes time, as the Cook Islands experience clearly shows. While the country is on the OECD list of countries to be graduated to developed country status, it is still a small island developing state, with vulnerabilities such as weak institutions, human resource capacity gaps, and financial constraints as capital investments take priority over operational investments. The experience indicates that poor investment and management decisions made in the past are being remedied, along with ambitious development aspirations for the future, including a firm appreciation of the need to enhance human resource capacity and to respond effectively to competing priorities drawing on a limited financial resources pool. These are significant challenges for any government to address. They require demand-driven, resilient and forward-thinking leaders and leadership. Disclosure statement No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authorStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

1 Expert Approved Answer

Step: 1 Unlock

Question Has Been Solved by an Expert!

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts

Step: 2 Unlock

Step: 3 Unlock