Question: . Required Question: Q.1 How do customers purchase air express services? Are these differences between documents and parcels? (150 words) Q.2 What are DHLs strengths

.

Required Question:

Q.1 How do customers purchase air express services? Are these differences between documents and parcels? (150 words)

Q.2 What are DHLs strengths and weaknesses compared to its competitors? (100 words)

Q.3 How does DHL set prices? (100 words)

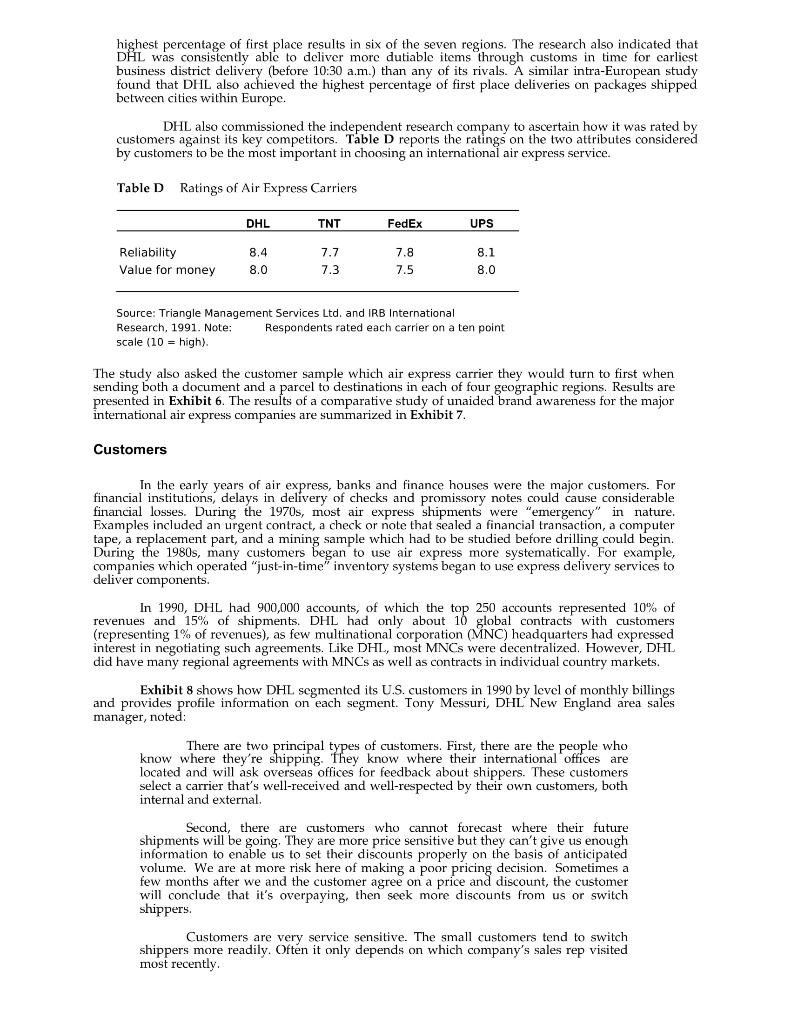

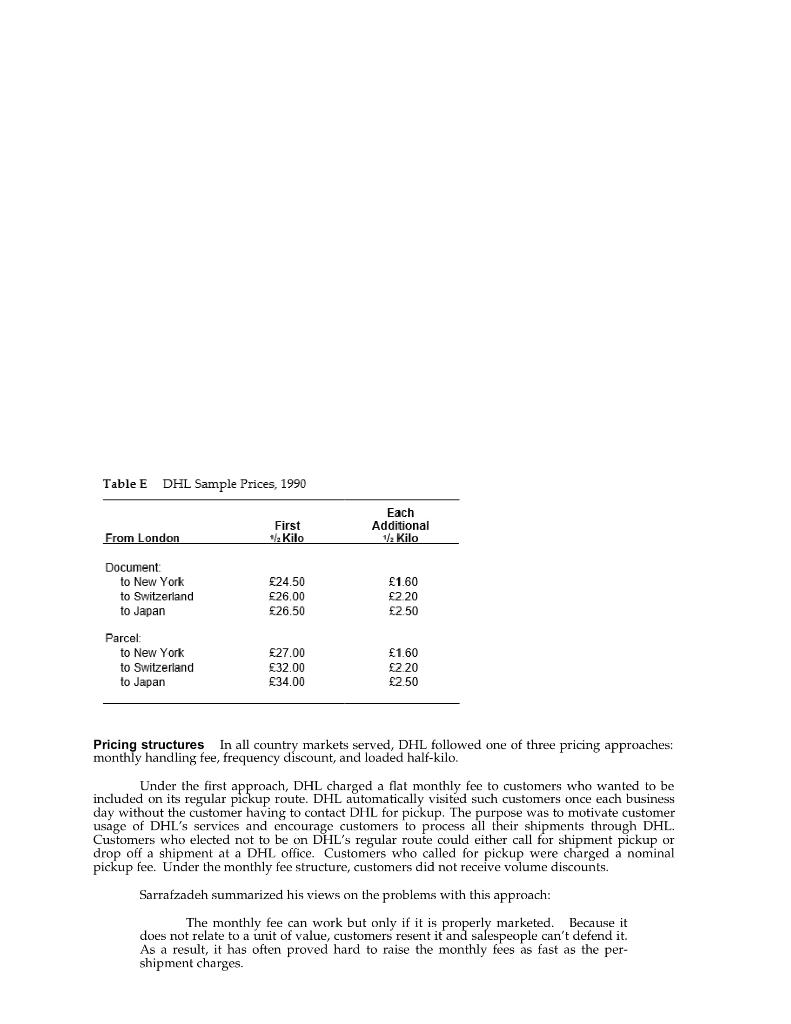

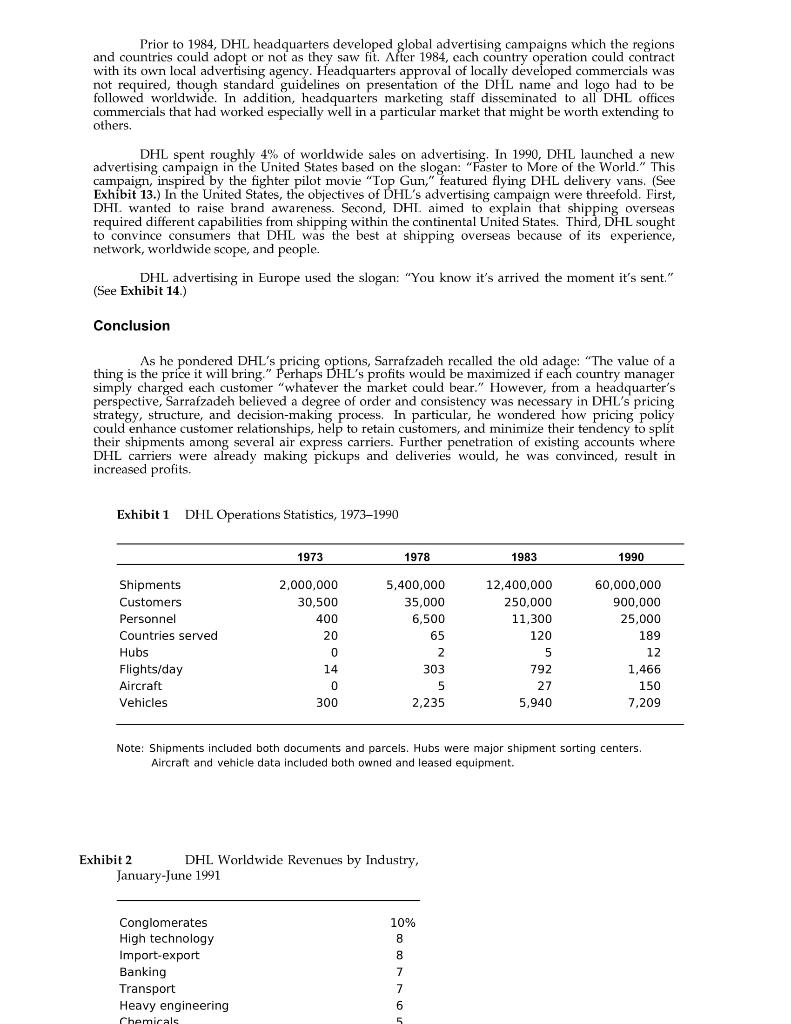

DHL Worldwide Express Company Background and Organization DHL legally comprised two companies: DHL Airways and DHL International. DHL Airways was based in San Francisco and managed all U.S. operations. DHL International was based in Brussels and managed all operations outside the United States. Each company was the exclusive delivery agent of the other. Revenues for 1990 were split: $600 million for DHL Airways, and $1,400 million for DHL International. One DHL executive commented, "The main reason DL is involved in domestic shipping within the United States is to lower the costs and increase the reliability of our international shipments. If not for our domestic business, we would be at the mercy of the domestic airlines bringing our packages to the international gateways." In 1990, DHL accounted for only 3% of intra-U.S. air express shipments but 20% of overseas shipments from the United States. DHL was the world's leading international express delivery network. It was privately held and headquartered in Brussels, Belgium. The company was formed in San Francisco in September 1969 by Adrian Dalsey, Larry Hillblom, and Robert Lynn. The three were involved in shipping and discovered that, by forwarding the shipping documents by air with an on-board courier, they could significantly reduce the turnaround time of ships in port. DHL grew rapidly and, by 1990, serviced 189 countries. In 1990, revenues were approximately s2 billion. Profits before taxes were 4%-6% of revenues. (Exhibit 1 summarizes the growth of DHL operations from 1973 to 1990; Exhibit 2 displays DHL's revenues by industry.) DHL used a hub system to transport shipments around the world. In 1991 the company operated 12 hubs (as shown in Exhibit 3). Within Europe, the United States, and the Middle East, DHL generally used owned or leased aircraft to carry its shipments, while on most intercontinental routes it used scheduled airlines. In 1991, approximately 65% of DHL shipments were sent via scheduled airlines and 35% via owned or leased aircraft. The other leading shippers also utilized scheduled airlines but to a lesser extent than DHL. Federal Express relied on its own fleet of planes to transport all its shipments. Pierre Madec, DHL's operations director, noted: FedEx has a dedicated airfleet which ties up capital and limits the flexibility of its operation: express packages are forced to wait until the FedEx plane's takeoff slot, which at major international airports frequently does not tie in with the end-of- the-day courier pickups. By using a variety of scheduled international carriers, DHL is able to optimize its transport network to minimize delivery times. DHL was organized into nine geographic regions. Region managers oversaw the relevant country managers and/or DHL agents in their regions and held profit and loss responsibility for performance within their territories. Revenues and profits were recognized at the location where a shipment originated. Only 70 people worked at DHL's world headquarters in Brussels. The main functions of the worldwide marketing services group, of which Sarrafzadeh was a member, were business development, information transfer, communication of best practice ideas, and sales coordination among the country operating units. Of DHL's 60 million shipments in 1990, 50 million were cross-border shipments. DHL's worldwide mission statement, included in its 1990 annual report, read: DHL will become the acknowledged global leader in the express delivery of documents and packages. Leadership will be achieved by establishing the industry standards of excellence for quality of service and by maintaining the lowest cost position relative to our service commitment in all markets of the world. DHL management believed that achievement of this mission required the following: Absolute dedication to understanding and fulfilling DHL's customers' needs with the appropriate mix of service, products, and price for each customer. Ensuring the long-term success of the business through profitable growth and reinvestment of earnings. An environment that rewards achievement, enthusiasm, and team spirit, and which offers each person in DHL superior opportunities for personal development and growth. A state-of-the-art worldwide information network for customer billing, tracking, tracing and management information/communications. Allocation of resources consistent with the recognition that DHL is one worldwide business. A professional organization able to maintain local initiative and local decision making while working together within a centrally managed network. DHL's annual report also stated: "The evolution of our business into new services, markets or products will be completely driven by our single-minded commitment to anticipating and meeting the changing needs of our customers. The International Air Express Industry Total revenues for the international air cxpress industry were approximately $3.4 billion in 1989 and $4.3 billion in 1990. The air express industry offered two main products: document delivery and parcel delivery. Industry revenues were split roughly 75:25 between parcels and documents. In 1989, the parcel sector grew 40%, while the document sector grew 15%. The growth of parcel and document express delivery was at the expense of the air cargo market and other traditional modes of shipping The growth of the air express industry was expected to continue. One optimistic forecast for 1992 is presented in Table A. Other observers were concerned that shipping capacity would expand faster than shipments, particularly if economic growth slowed. Table A Worldwide International (Cross-Border) Air Express 1992 Estimated Revenue Growth Rates Market 1992 Estimated Growth Rate Europe Asia/Pacific United States Rest of the world Total 28% 30 25 9 25% Note: Growth rates are for time-sensitive documents/packages under 30 kilograms. Acknowledging continuing progress toward completion of the European market integration program by the end of 1992, an article on the air express industry in Europe in Forbes (April, 1991) noted: The express-delivery business in Europe is booming.... Measured by revenues, the European express-delivery business is growing at a 28% compound annual rate. Big European companies are stocking products and parts in central locations and moving them by overnight express, instead of running warehouses in each country. Competitors Air express companies serviced a geographic region either by using their own personnel or by hiring agents. Building a comprehensive international network of owned operations and/or reliable agents required considerable time and investment and therefore, acted as a significant barrier to entry. DHL's principal competitors in door-to-door international air express delivery were Federal Express, TNT, and UPS. (Exhibit 4 provides operational data for the top four competitors; Table B summarizes their 1988 market shares.) Table B International Air Express Market Shares by S Revenue (1988) Company Market Share (% DHL 44% FedEx TNT UPS Others Total 7 18 4 27 100% Founded in 1973, FedEx focused for many years on the U.S. domestic market. During the late 1980s, the company began to expand internationally through acquisitions and competitive pricing, sometimes undercutting DHL published prices by as much as 50%. Between 1987 and 1991, FedEx invested over $1 billion in 14 acquisitions in nine countries: the United Kingdom, Holland, West Germany, Italy, Japan, Australia, United Arab Emirates, Canada, and the United States. FedEx also entered the international air freight business through the acquisition of Tiger International (Flying Tigers), which expanded further FedEx's global reach in document as well as parcel delivery, particularly in Asia. However, the challenge of integrating so many acquisitions meant that FedEx's international operations lost $43 million 1989 and $194 million in 1990. Nevertheless, with 45% of the U.S. air express market, 7% of the European market, and leadership in value-added services based on information systems technology, FedEx remained a formidable competitor. Thomas Nationwide Transport (TNT) was a publicly owned Australian transport group which had historically concentrated on air express delivery of documents. TNT focused mainly on Europe and had a low profile in North America. To participate in the North American market, 'INT held a 15% stake in an American shipper-Airborne Freight Corporation. This stake could be increased to a maximum holding of only 25% under U.S. aviation laws. During the late 1980s, TNT began to target heavier shipments and bulk consolidations to fuel its growth. United Parcel Service (UPS) was a privately held U.S. company, most of whose equity was owned by its employees. UPS had traditionally been known as a parcel shipper that emphasized everyday low prices rather than the fastest delivery. Unlike DHL, UPS sometimes held a package back to consolidate several shipments to the same destination in the interest of saving on costs. UPS had historically tried to avoid offering discounts from its published prices. UPS's 1990 annual report proclaimed the company's strategy as follows: UPS will achieve worldwide leadership in package distribution by developing and delivering solutions that best meet our customers' distribution needs at competitive rates. To do so, we will build upon our extensive and efficient distribution network, the legacy and dedication of our people to operational and service excellence and our commitment to anticipate and respond rapidly to changing market conditions and requirements. In addition to the industry giants, there were many small shipping forwarders which concentrated on a specific geographic area or industry sector. In the late 1980s, many of these small companies were acquired by larger firms trying to increase their market shares. National post offices were also competitors in air express, but they could not offer the same service and reliability because they were not integrated across borders (that is, no nation office could control the shipment of a package from one country to another). One industry executive commented: When we have internal competitive discussions on international business, the post offices just don't come up." Finally, the regular airlines were minor competitors in door-to-door express delivery. British Airways operated a wholesale airport-to-door courier service called Speedbird in cooperation with smaller couriers that did not have international networks. Swissair serviced 50 countries through its Skyracer service in cooperation with local agents. In the heavy cargo sector, most airlines were allied with freight forwarders who consolidated cargo from different sources and booked space in aircraft. These alliances represented significant competition as DHL expanded into delivery of heavier shipments. Some airlines were reluctant to upset their freight forwarder customers by dealing with integrated shippers such as DHL. Competition in the air express industry, aggravated by excess capacity, had resulted in intense price competition during the late 1980s.' DHL's chairman and CEO L. Patrick Lupo estimated that prices had dropped, on average, 5% each year from 1985 to 1990, with extreme price drops in some markets. For example, in Great Britain, DHL's list prices for shipments to the United States fell approximately 40% from 1987 to 1990. Some of the price reductions were offset, in part, by rising volume and productivity, yet Lupo noted, "There's no question that margins have been squeezed." DHL Services DHL offered two services: Worldwide Document Express (DOX) and Worldwide Parcel Express (WPX). DOX offered document delivery to locations around the world within the DHL network. DOX was DHL's first product and featured door-to-door service at an all-inclusive price for nondutiableondeclarable items. Typical items handled by DOX included interoffice correspondence, computer printouts, and contracts. The number of documents sent to and from each DHL location was, in most cases, evenly balanced. WPX was a parcel transport service for nondocument items that had a commercial value or needed to be declared to customs authorities. Like DOX, WPX offered door-to-door service at an all- inclusive price that covered DHL's handling of both the exporting and importing of the shipment. Typical items handled by WPX included prototype samples, spare parts, diskettes, and videotapes. DHL imposed size, weight, and content restrictions for all parcels. The size of a package could not exceed 175 centimeters in exterior dimensions (length + width + height), and the gross weight could not exceed 50 kilograms. Further, DHL would not ship various items such as firearms, hazardous material, jewelry, and pornographic material. Table C compares DHL's parcel and document businesses for 1990, Table C DHL's Document and Parcel Businesses, 1990 Total Revenues Growth (1989-90) Total Shipments Total Weight Gross Profits Revenues Document 60% 70% 50% 53% Parcel 40% +14 % +28 % 30% 50% 47% DHL offered numerous value-added services, including computerized tracking (LASERNET), 24-hour customer service every day of the year, and proof of delivery service. Customers could also tap the assistance of specialized industry consultants based in DHL regional offices. Such value added services could enhance customer loyalty and increase DHL'S share of a customer's international shipping requirements. However, such services were expensive to provide and customers using them were often not always charged extra, particularly since those services were also offered by key competitors such as FedEx. DHL had 20 years of experience in dealing with customs procedures and, by 1990, was electronically linked into an international customs network. All shipments were bar coded, which facilitated computerized sorting and tracking. Thanks to a direct computer link between DHL and customs authorities in 5 European countries, customs clearance could occur while shipments were en route. In addition, DHL's staff included licensed customs brokers in 80 countries, DHL had been cautious about differentiating itself on the basis of speed of service, and arrival times were not guaranteed. However, DHL executives believed that their extensive network meant that they could deliver packages faster than their competitors. Hence, in 1991, DHL commissioned an independent research company to send on the same day five documents and five dutiable packages from three U.S. origin cities via each of five air express companies to 21 international destinations (three cities in each of seven regions). Exhibit 5 reports the percentages of first place deliveries (i.e., fastest deliveries) achieved by each competitor in each region. DHL had the highest percentage of first place results in six of the seven regions. The research also indicated that DL was consistently able to deliver more dutiable items through customs in time for carliest business district delivery (before 10:30 a.m.) than any of its rivals. A similar intra-European study found that DHL also achieved the highest percentage of first place deliveries on packages shipped between cities within Europe. DHL also commissioned the independent research company to ascertain how it was rated by customers against its key competitors. Table D reports the ratings on the two attributes considered by customers to be the most important in choosing an international air express service. Table D Ratings of Air Express Carriers DHL TNT FedEx UPS Reliability Value for money 8.4 8.0 7.7 7.3 7.8 7.5 8.1 8.0 Source: Triangle Management Services Ltd. and IRB International Research, 1991. Note: Respondents rated each carrier on a ten point scale (10 = high). The study also asked the customer sample which air express carrier they would turn to first when sending both a document and a parcel to destinations in each of four geographic regions. Results are presented in Exhibit 6. The results of a comparative study of unaided brand awareness for the major international air express companies are summarized in Exhibit 7. Customers In the early years of air express, banks and finance houses were the major customers. For financial institutions, delays in delivery of checks and promissory notes could cause considerable financial losses. During the 1970s, most air express shipments were "emergency" in nature. Examples included an urgent contract, a check or note that sealed a financial transaction, a computer tape, a replacement part, and a mining sample which had to be studied before drilling could begin. During the 1980s, many customers began to use air express more systematically. For example, companies which operated "just-in-time" inventory systems began to use express delivery services to deliver components. In 1990, DHL had 900,000 accounts, of which the top 250 accounts represented 10% of revenues and 15% of shipments. DHL had only about 10 global contracts with customers (representing 1% of revenues), as few multinational corporation (MNC) headquarters had expressed interest in negotiating such agreements. Like DHL, most MNCs were decentralized. However, DHL did have many regional agreements with MNCs as well as contracts in individual country markets. Exhibit 8 shows how DHL segmented its U.S. customers in 1990 by level of monthly billings and provides profile information on each segment. Tony Messuri, DHL New England area sales manager, noted: know where they're spipping types of customers. First, there are the people who know where their international offices located and will ask overseas offices for feedback about shippers. These customers select a carrier that's well-received and well-respected by their own customers, both internal and external. are Second, there are customers who cannot forecast where their future shipments will be going. They are more price sensitive but they can't give us enough information to enable us to set their discounts properly on the basis of anticipated volume. We are at more risk here of making a poor pricing decision. Sometimes a few months after we and the customer agree on a price and discount, the customer will conclude that it's overpaying, then seek more discounts from us or switch shippers Customers are very service sensitive. The small customers tend to switch shippers more readily. Often it only depends on which company's sales rep visited most recently, The parcel market was typically more price sensitive than the document market. For most companies, the total cost of shipping parcels was a much larger line item than the total cost of shipping documents. Further, the decision-making unit was often different for the two services. The decision on how to ship a document was frequently made by an individual manager or secretary. As one shipper stated, "Documents go out the front door, whereas parcels go out the back door." Parcels were shipped from the loading dock by the traffic manager who could typically select from a list of carriers approved by the purchasing department. In some companies, parcel shipment decisions were being consolidated, often under the vice president of logistics. As one European auto parts supplier stated: We view parts delivery as a key component of our customer service." As a result, many customers split their air express business among several firms. For example, all documents might be shipped via DHL, while parcels might be assigned to another carrier. Alternatively, the customer's business might be split by geographic region; a multinational company might assign its North American business to Federal Express and its intercontinental shipments to DHL. For the sake of convenience and price leverage, most large customers were increasingly inclined to concentrate their air express shipments worldwide with two or three preferred suppliers Pricing Evolution of pricing policy As DHL expanded service into new countries throughout the 1970s and 1980s, it developed many different pricing strategies and structures. DHL country managers had almost total control of pricing. They typically set prices based on four factors: what the market could bear, prices charged by competition (which was often initially the national post office), DHL's initial entry pricing in other countries, and DHL's then-current pricing around the world, DHL's prices were historically 20% to 40% higher than those of competitors. (Exhibit 9 provides sample prices for DHL, TNT, FedEx, and UPS) In most countries, DHL published a tariff book which was updated yearly. Competitors who followed DHL into new markets often patterned their pricing structures after DHL's. DHL had developed a sophisticated, proprietary software package called PRISM to analyze profitability. A PRISM staff officer at each regional office advised and trained country operating units on use of the software. The program could calculate profitability by route or by customer in a given country. However, PRISM could not consolidate the profits of a given customer across countries. (Exhibit 10 provides a fuller description of PRISM.) All profitability analyses had to be based on average costs due to the variability in costs associated with transporting a shipment. For example, a package from Perth, Australia, to Tucson, Arizona, might be consolidated seven to eight times in transit and travel on five to six planes. Further, every package from Perth to Tucson did not necessarily travel the same route. (Exhibit 11 shows the revenues and costs associated with two sample lanes to illustrate the significant impact of geographical differences on costs and profitability.) PRISM was not used extensively by all DHL offices. As one country manager put it: "We and the customer both want a simple pricing structure. PRISM just provides more information, adds to complexity, and takes time away from selling." Base prices and options DHL's base prices were calculated according to product (service), weight, origin, and destination. Prices were often higher for parcels than for documents of equivalent weight due to extra costs for customs clearance, handling, packaging, and additional paperwork. FedEx charged the same for parcels and documents. Shipment weights were computed in pounds in the United States and in kilograms in all other countries. Moreover, weight breaks varied among countries. For example, in Hong Kong breaks were every half kilogram, and in Spain, every two kilograms. Some DHL executives believed that, for the sake of simplicity, DHL's weight breaks should be the same worldwide. (Table E gives examples of base prices on routes from London.) Table E DHL Sample Prices, 1990 Each Additional 1/2 Kilo First 12 Kilo From London $24.50 Document to New York to Switzerland to Japan 26.00 26.50 1.60 2.20 250 Parcel to New York to Switzerland to Japan 27.00 32.00 $34.00 1.60 2.20 2.50 Pricing structures In all country markets served, DHL followed one of three pricing approaches: monthly handling fee, frequency discount, and loaded half-kilo. Under the first approach, DHL charged a flat monthly fee to customers who wanted to be included on its regular pickup route. DHL automatically visited such customers once each business day without the customer having to contact DHL for pickup. The purpose was to motivate customer usage of DHL's services and encourage customers to process all their shipments through DHL. Customers who elected not to be on DHL's regular route could either call for shipment pickup or drop off a shipment at a DHL office. Customers who called for pickup were charged a nominal pickup fee. Under the monthly fee structure, customers did not receive volume discounts. Sarrafzadeh summarized his views on the problems with this approach: The monthly fee can work but only if it is properly marketed. Because it does not relate to a unit of value, customers resent it and salespeople can't defend it. As a result, it has often proved hard to raise the monthly fees as fast as the per- shipment charges. In some markets, including Great Britain, DHL offered a frequency discount structure under which a discount was provided based on number of units shipped. The more often a customer used DHL during a given month, the cheaper the unit shipment cost. The frequency discount was based on the total number of documents and parcels shipped. For example, if a customer purchased 10 document and 20 parcel shipments in a given month, it received a discount of 10 per shipment. Under the frequency discount structure, a customer did not pay a standard monthly route fee and DHL visited the account only upon request. The per-shipment frequency discount was retroactive and was computed for each customer at the end of the calendar month. Conversely, FedEx's discounts were based on forecast demand rather than past performance and on revenues rather than unit shipments. FedEx monitored a new account's actual shipments for six months before the account qualified for a discount and then adjusted the discount upward or downward based on quarterly shipment data and shipment density Price negotiations The largest customers sought one- or two-year deals with shippers to handle their transport needs. Typically, when a current agreement was nearing its end, the customer put its business up for bid and solicited proposals from interested shippers. Proposals incorporated the following information transit times, overhead rate structures, rates for specified countries, tracking capabilities, sample tracking reports, sample annual activity report, and a list of international stations (indicating which were company-owned versus run by agents). Most bid requests were made by the purchasing manager, yet the decision-making unit was often a committee comprising managers from the traffic, sales and marketing, customer service, and purchasing departments. The decision was complicated because the major shippers were organized into different regions and lanes, thereby hindering direct comparisons among proposals. Sophisticated accounts typically calculated the bottom-line cost of each proposal, while unsophisticated accounts based their decisions on comparisons on a few "reference prices" (e.g., New York-London). The average term of shipping agreements was two years, with almost all ranging between one and three years. Fifteen percent of DHL agreements involved formal contracts, while the other 85% were "handshake" agreements. Some customers tried to renegotiate prices in the middle of an agreement, though most Fortune 2000 companies abided by their deals. DHL sales reps had significant flexibility when negotiating proposals. For example, the rep could tailor discount rates by lane such that an account would obtain large discounts on its most frequently used routes. DHL senior management typically gave only general direction to sales reps on negotiating discounts. For example, senior management might advise, "Hold price on Asia, yet you can give some on the United States and Europe." Most proposals associated a monthly minimum level of billings (adjusted, if necessary, for seasonality of the business) with the offer of any discounts. DHL sales reps could negotiate discounts from book prices up to 35%. District sales managers could approve discounts up to 50%, while discounts above 50% required the approval of a regional sales director. Further, discounts over 60% required approval from the vice president of sales. For all discounts over 35%, a sales rep had to submit a Preferred Status Account (PSA) report, which included a detailed analysis of the profitability of the account. As shown in Exhibit 12, the PSA used a computer model to calculate fixed and variable costs, net profits by geographic lane and product line, and overall contribution margins. When deciding on the discount, management considered not only the financial implications of the discount but also competitive and capacity factors. Sales and Advertising DHL had a single sales force which sold both document and parcel services. Sales reps were organized geographically and were evaluated primarily on monthly sales. Typically, sales reps had separate monthly sales objectives for international, domestic, and total sales and received a bonus whenever they exceeded any one of the three. Sales managers were evaluated against profit as well as revenue objectives. When a new account called for a pickup, that account was assigned an account number the next day and was called upon by a DHL sales rep within a week. At large companies, sales reps targeted the traffic, shipping and receiving, and purchasing departments, while at small companies, they focused their efforts on line managers such as the vice president of marketing or vice president of International. Prior to 1984, DHL headquarters developed global advertising campaigns which the regions and countries could adopt or not as they saw fit. After 1984, cach country operation could contract with its own local advertising agency. Headquarters approval of locally developed commercials was not required, though standard guidelines on presentation of the DHL name and logo had to be followed worldwide. In addition, headquarters marketing staff disseminated to all DHL offices commercials that had worked especially well in a particular market that might be worth extending others. DHL spent roughly 4% of worldwide sales on advertising. In 1990, DHL launched a new advertising campaign in the United States based on the slogan: "Faster to More of the World." This campaign, inspired by the fighter pilot movie "Top Gun," teatured flying DHL delivery vans. (See Exhibit 13.) In the United States, the objectives of DHL's advertising campaign were threefold. First, DHI wanted to raise brand awareness. Second, DHL aimed to explain that shipping overseas required different capabilities from shipping within the continental United States. Third, DHL sought to convince consumers that DHL was the best at shipping overseas because of its experience, network, worldwide scope, and people. DHL advertising in Europe used the slogan: "You know it's arrived the moment it's sent." (See Exhibit 14.) Conclusion As he pondered DHL's pricing options, Sarrafzadeh recalled the old adage: "The value of a thing is the price it will bring." Perhaps DHL's profits would be maximized if each country manager simply charged each customer "whatever the market could bear." However, from a headquarter's perspective, Sarrafzadeh believed a degree of order and consistency was necessary in DHL's pricing strategy, structure, and decision-making process. In particular, he wondered how pricing policy could enhance customer relationships, help to retain customers, and minimize their tendency to split their shipments among several air express carriers. Further penetration of existing accounts where DHL carriers were already making pickups and deliveries would, he was convinced, result in increased profits. Exhibit 1 DHL Operations Statistics, 19731990 1973 1978 1983 1990 Shipments Customers Personnel Countries served Hubs Flights/day Aircraft Vehicles 2,000,000 30,500 400 20 0 14 D 300 5,400,000 35,000 6,500 65 12,400,000 250,000 11.300 120 5 792 27 5,940 60,000,000 900,000 25,000 189 12 1,466 150 7,209 303 5 2,235 Note: Shipments included both documents and parcels. Hubs were major shipment sorting centers. Aircraft and vehicle data included both owned and leased equipment. Exhibit 2 DHL Worldwide Revenues by Industry, January-June 1991 Conglomerates High technology Import-export Banking Transport Heavy engineering 10% 8 8 7 7 6 ChemicalsStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Q1 How do customers purchase air express services Are there differences between documents and parcels 150 words Customers purchase air express services through different channels based on their shipme... View full answer

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts