Question: Summarize the above Journal Article - Pricing to Create Shared Value by including a critical evaluation and analysis on what you learn, what you agree

Summarize the above Journal Article - Pricing to Create Shared Value by including a critical evaluation and analysis on what you learn, what you agree or disagree with, and your comments (Minimum 1000 words). Please provide proper citations (in APA Format) with information from books/websites.

*PLEASE TYPE YOUR ANSWER (NO SCREENSHOTS OR IMAGES) IN FULL SENTENCE/PARAGRAPH/REPORT FORMAT, NO POINT FORM. THANK YOU IN ADVANCE

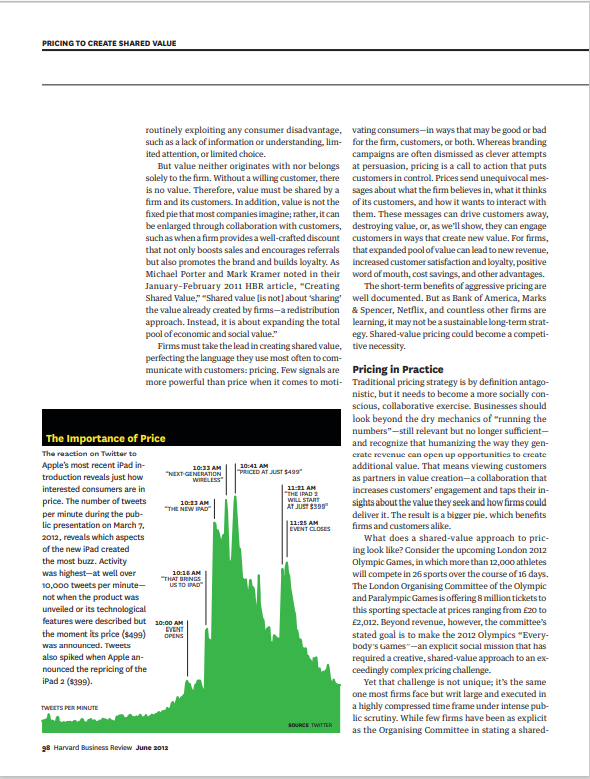

HBR.ORG Marco Bertini is an assis tant professor of marketing at London Business School. John T. Gourville is the Albert J. Weatherhead Jr. Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School 112 Rethinking the way prices are set can expand the pie for everyone. by Marco Bertini and John T. Gourville T he way most companies WHEN NETFLIX implemented a 60% price in- make money is not just crease in July 2011 for customers who both rented broken; it's destructive. DVDs and streamed video, 800,000 users cancelled From insurance and finantheir service and the company's market cap plum- cial services to telecom- meted by more than 70% munications and air travel, AND WHEN MARKS & SPENCER was targeted by companies use pricing to irate consumers in 2008 for charging 2.00 more extract what they can from for bras with large cups, the British retailer initially every transaction. Look, defended the practice, pointing to the higher cost of for example, at how air- goods. But as the complaint gained traction on social lines siphon off value. Once a customer buys a ticket, media, the company relented, implementing a "one the slow bleed begins. Want extra legroom? Pay us. price fits all" policy and offering a monthlong 25% Want to check a bag? Pay us. Want a pillow or some discount on all bras. thing to eat? Pay us. This antagonistic approach may have worked in the past. But today's consumers are The challengeand the opportunity for compa- not passive price takers. They root out and dissemi- nies is profound. Consumers aren't simply rejecting nate information about a firm's prices, exploiting so- questionable prices; they're rejecting many firms cial media platforms to publicize policies that they fundamental approach to making money. believe are unfair. And they don't hesitate to aban- Here's the problem:Companies have traditionally don companies that cross the line. treated value in the marketplace as a fixed ple and Consider the swift responses to companies have reasoned that they must compete with their whose aggressive pricing consumers deemed unjust: customers to appropriate as much of it as those cus- WHEN BANK OF AMERICA announced in Sep-tomers will relinquish. Whatever value they can ex- tember 2011 that it would start charging a $5 tract is value customers miss out on, and vice versa. monthly debit card fee, the public outcry was so What's more, firms have presumed that they are the intense that the bank soon rescinded the plan. But rightful owners of value and are therefore entitled the damage was done: Account closings in the final to charge whatever the market will bear. To that end, months of 2011 increased 20% compared with the they have treated pricing as an optimization prob- same period in 2010. lem, pricing mechanically in the pursuit of profit and ILLUSTRATION PEER GRUNDY June 2012 Harvard Business Review 97 PRICING TO CREATE SHARED VALUE routinely exploiting any consumer disadvantage, vating consumers-in ways that may be good or bad such as a lack of information or understanding, lim- for the firm, customers, or both. Whereas branding ited attention, or limited choice. campaigns are often dismissed as clever attempts But value neither originates with nor belongs at persuasion, pricing is a call to action that puts solely to the firm. Without a willing customer, there customers in control. Prices send unequivocal mes is no value. Therefore, value must be shared by a sages about what the firm believes in, what it thinks firm and its customers. In addition, value is not the of its customers, and how it wants to interact with fixed pie that most companies imagine; rather, it can them. These messages can drive customers away, be enlarged through collaboration with customers, destroying value, or, as we'll show, they can engage such as when a firm provides a well-crafted discount customers in ways that create new value. For firms, that not only boosts sales and encourages referrals that expanded pool of value can lead to new revenue, but also promotes the brand and builds loyalty. As increased customer satisfaction and loyalty, positive Michael Porter and Mark Kramer noted in their word of mouth.cost savings, and other advantages. January-February 2011 HBR article, "Creating The short-term benefits of aggressive pricing are Shared Value," "Shared value [is not about sharing well documented. But as Bank of America, Marks the value already created by firms-a redistribution & Spencer, Netflix, and countless other firms are approach. Instead, it is about expanding the total learning, it may not be a sustainable long-term strat- pool of economic and social value." egy. Shared-value pricing could become a competi- Firms must take the lead in creating shared value, tive necessity. perfecting the language they use most often to com- municate with customers: pricing. Few signals are Pricing in Practice more powerful than price when it comes to moti- Traditional pricing strategy is by definition antago- nistic, but it needs to become a more socially con- scious, collaborative exercise. Businesses should look beyond the dry mechanics of "running the numbers"-still relevant but no longer sufficient- The Importance of Price and recognize that humanizing the way they gen- The reaction on Twitter to crate revenue can open up opportunities to create Apple's most recent iPad in- additional value. That means viewing customers troduction reveals just how "NEXT GENERATION as partners in value creation-a collaboration that interested consumers are in 11:11 AM THE IPAD 2 increases customers' engagement and taps their in- price. The number of tweets 10:23 AM WILL START "THE NEW IPAD AT JUST $999 sights about the value they seek and how firms could per minute during the pub- deliver it. The result is a bigger pie which benefits lic presentation on March 7. 11:25 AM EVENT CLOSES firms and customers alike. 2012, reveals which aspects What does a shared-value approach to pric- of the new iPad created ing look like? Consider the upcoming London 2012 the most buzz. Activity Olympic Games, in which more than 12,000 athletes was highest-at well over 10:16 AM will compete in 26 sports over the course of 15 days. THAT BRINGS 10,000 tweets per minute- US TO IPAD The London Organising Committee of the Olympic not when the product was and Paralympic Games is offering 8 million tickets to unveiled or its technological this sporting spectacle at prices ranging from 20 to features were described but 10:00 AM 2,012. Beyond revenue, however, the committee's EVENT the moment its price (499) OPENS stated goal is to make the 2012 Olympics "Every- was announced. Tweets body's Games"-an explicit social mission that has also spiked when Apple an- required a creative, shared-value approach to an ex- nounced the repricing of the ceedingly complex pricing challenge. iPad 2 (1999) Yet that challenge is not unique; it's the same one most firms face but writ large and executed in TWEETS PER MINUTE a highly compressed time frame under intense pub- lic scrutiny. While few firms have been as explicit as the Organising Committee in stating a shared- 98 Harvard Business Review June 2012 10:33 AM WIRELESS 10:41 AM PRICED AT JUST $499" SOURCE TWITTER HBR.ORG MANAGE THE MARKET'S STANDARDS POR FAIRNESS. nale for your pricing Make sure that Idea in Brief Companies have long used pricing to extract as much value as they can from transactions. This approach is destructive in two ways: It antago- nizes customers, who are quick to punish companies they feel abuse them, and it fails to create new value that can benefit both the company and its customers. Companies must take the lead in creating shared value with customers. Five pricing strate- gies can help. FOCUS ON BE PROACTIVE PUTA PREMIUM PROMOTE RELATIONSHIPS, NOT Set prices in ways ON FLEXIBILITY TRANSPARENCY. ON TRANSACTIONS that encourage Design pricing so Provide the ratio Use pricing to com customer behavior that it can change municate that you that benefits both in response to shift to consumers. value your custom the firm and your ing consumer needs ers as people, not customers. and ensure the as wallets. equitable sharing of value your pricing meets customers' expecta tions about what is fair and that the pricing process is clear. value mission, most can nonetheless learn from the multiyear process used to devise the Games pricing. (See the sidebar "Pricing Lessons from the London Olympics.") Our in-depth study of the 2012 Games, detailed in a Harvard Business School teaching case (HBS Case 510-039), suggests five pricing principles that every business could profitably adopt. Focus on relationships, not on transactions. Consumers often come to identify with the brands they buy, and firms hope to encourage this, prefer- ring loyal customers to ones who engage on amerely transactional basis. But pricing decisions often un- dermine the relationship between brands and their followers. While a firm's brand communications may say, "We value you as a person," its pricing practices often say, "We value you as a wallet." Cus- tomers instantly pick up on the inconsistency and respond accordingly. Consider the World Triathlon Corporation (WTC), a U.S.-based, for-profit company founded in 1990, which organizes, promotes, and licenses triathlons under the Ironman brand. To triathletes and sports enthusiasts, the Ironman name was synonymous with extreme physical challenge and camaraderie through disciplined training. Beginning in 2008, however, when a private equity firm acquired the WTC, loyal followers sensed a shift from those core values to commercialization. First, the company decided that people who finished half-Ironman races also A firm's brand should have the right to call them- communications may selves "Ironmen." Second, it greatly say, "We value you as expanded its licensing agreements, a person," but its pricing leading to the introduction of du- bious Ironman-branded products practices often say, such as a mattress, a cologne, and a "We value you jogging stroller. Third, and most vis- as a wallet." ibly, in October 2010 it launched Iron- man Access, a membership program that allowed preferential access to hard-to-enter Iron- man events-for a $1,000 annual fee. The response was quick and decisive. Serious triathletes overwhelmingly criticized the move as a money grab, inconsistent with the true character of the brand. They rejected any attempt by the WTC to rationalize the value of the program for customers and mobilized an online protest that forced the com- pany to rescind the program and post an apology the day following its introduction. The message many triathletes got from the commercialization efforts was that the WTC cared more about monetizing the Ironman brand than about the customer relation- ships that had sustained the brand. Compare WTC's actions with those of Hilti, the European maker of high-end power tools. In an industry accustomed to selling tools to construc- tion companies, Hilti decided to provide a service instead. Customers subscribing to Hilti's Fleet Man- agement program pay a monthly fee- customized to fit their business models-that CONTINUED ON PE June 2012 Harvard Business Review 99 PRICING TO CREATE SHARED VALUE CASE STUDY Focus on Relationships, Not on Transactions Pricing Lessons From the London Olympics The committee organizing the London 2012 Olympic Games faced an extraordinary business challenge: How to price 8 million tickets in a way that allows equitable access to 26 sporting events, meets revenue and attendance targets, and adheres to the explicit social objective of making the Olympiad "Everybody's Games." To accomplish this, the committee applied all five principles of shared-value pricing, integrating them more completely than any other organization we've seen. The committee understood early on that it was in various relation ships with the British government with the British public, with the International Olympic Committee and so on- and that ticketing was the most visible aspect of those relationships. As one committee member put it, tickets account for 20% of the Games' revenue but when done wrong result in 80% of an organizer's headaches. The solution was to value customers more than their money. First, the committee increased the number of pricing tiers for many sports, which kept some ticket prices low while still hitting revenue targets. Second, it offered a pay your age pricing plan for young customers and discounted tickets to those over 6o. Third, for the opening ceremony it chose high and low price points--20.12 and 3,012, respectively-whose symbolic rationale everyone under stood. Finally, it instituted a strict policy of no free tickets, avoiding the public outrage free tickets had provoked at previous Olympica. To many, these actions said, "We are looking out for you." Be Proactive Consider the committee's decision not to bundle tickets to a more popular sport (swimming, say) with those to a less popular sport (taekwondo, for instance), a tactic sometimes used in previous Olympics to increase ticket sales and boost attendance at the less popular events. While bundling can increase revenues, it can also add costs for consumers and doesn't necessarily fill seats. Indeed, past experience with bundling sug gested that many who purchased the bundle let the tickets to the secondary event go to waste. To avoid this problem, the com- mittee let the ticketing of every sport stand on its own, creating 26 different pricing plans detailing how tickets should be promoted and sold to the appropriate target markets. Interestingly, however, the committee did bundle public trans portation into the ticket price, rec ognizing the opportunity to reduce traffic congestion in and around the venues. By pricing proactively in this way, the committee discour aged one type of behavior (not attending events) and encouraged another (using public transporta tion), benefiting both spectators and the Games HBR.ORG Put a Premium On Flexibility The committee had to price all events more than a year and a half in advance of the Games, before it had a clear understanding of demand. To manage the uncer tainty, the committee increased the number of price tiers across events, as mentioned, but did not assign a fixed number of seats to each tier. It did, however, promise that some one paying more would have a bet ter view of the event than someone paying less. In the spring of 2011, fans placed requests for tickets through an online ballot, thereby revealing how much they were will ing to pay for various events. This allowed the committee to gauge demand at each price point and reallocate some stats accordingly. By not predetermining the number of seats in each tier, the committee had the flexibility to better satisfy actual rather than anticipated de mand, which resulted in more seats sold and happier customers. Manage the Market's Standards for Fairness Ask Londoners about the Olympic Games, and many say that they de serve to attend the most desirable events at reasonable prices. After all, they financed and endured the construction. But not everyone who wants to attend a particular event will be able to obtain a ticket, and some tickets may seem unreason ably priced. The committee took two impor tant steps to manage these and other expectations: First, from the moment the ticketing process be gan, the committee heavily commu- nicated the pay your age and senior discounts and the percentage of tickets that would be sold at 2D, at or below 30, and so on. Yes, there would be some very expen sive tickets, and the British press would surely comment on that fact, but the committee wanted the general public to realize that without the expensive tickets there would be fewer inexpensive ones. , any suggestion to auction the ticke ets in highest demand or to allow secondary exchanges above face value. Instead, ticket allocation was carried out through a simple lottery. reinforcing the fact that there was no preferential treatment. Promote Transparency This being England, the commit tee knew its actions would be subject to intense public scrutiny, especially in the British tabloids. One of the explicit goals in pricing the Games was to limit negative media attention. From very early on, therefore, the committee issued a continuous flow of information to consumers and the media about the rationale and process of ticket ing, the major dates in the ticketing timeline, the price tiers for each sport, the number of tickets avail able, and the distribution of tickets to corporate sponsors and the general public. To date, the efforts have been largely successful, with the media's attempts to stir contro versy largely falling on deaf ears. June 2012 Harvard Business Review 101 HBR.ORG end, the firm is aggressively moving away from Telecom, a subsidiary of China Telecom, improve pricing products to pricing the incremental value both its relations with customers and its bottom line. created in each partnership. For example, SKF may In 2005, when managers saw customer satisfaction take over a customer's maintenance operations and slipping, they took a close look at the complex bills agree to split the monetary savings that accrue from that had long prompted inquiries and complaints. the advanced knowledge SKF brings to the task. Be- The firm redesigned and simplified the bills to pro- cause each customer engagement is unique, each vide detailed and useful information in a way that customer has its own price, which is a function of was intuitive and comprehensible. These seemingly the shared value that is created. cosmetic changes halved the number of complaints Promote transparency. Afirm that is transpar- to the call center in a matter of months-which trans- ent about the way it makes money fosters engage- lated to substantial cost savings and fewer delayed ment and builds trust and goodwill among custom- payments. It also improved customer satisfaction ers. Engaged customers cost less to retain, often and loyalty. In many service industries, the invoice migrate to higher-end products or invest in acces- is a firm's only communication with customers. A sories and additional services, provide more useful clear, simple bill sends a powerful message that the feedback and product innovation ideas, and are firm cares about engaging honestly with them. more forgiving of mistakes. Conversely, a firm that is Manage the market's standards for fairness. less transparent signals that it has something to hide, Finally, it's crucial to understand and be able to in- distancing itself from its customers and putting both fluence consumers' perceptions of pricing fairness. parties on the defensive. It is no surprise that many When prices seem fair, consumers often buy more of the sectors with the worst customer satisfaction and are more willing to pay a premium. Conversely, scores also have the most extensive product lines, when prices seem unfair, consumers may punish complicated pricing plans, and obscure contractual companies. Critically, perceptions of fairness relate terms-in other words, the most opaque relation- not only to final prices but also to the process by ships with customers. which they are set. Retail banking offers perhaps the clearest exam- Consider the widely reviled online ticketing ple of this (sadly, one can pick almost any major bank company Ticketmaster (Wired magazine captured to make the point). For years, banks made significant the sentiment in the 2010 article "Everyone Hates profits on a charge known as an overdraft fee-apen- Ticketmaster-But No One Can Take It Down"). The alty that few customers ever anticipated but many. company's problem can be traced to the failure to especially those in lower-income households, fell manage public expectations of what is "fair" in the victim to. In 2009 alone, U.S.consumers paid more ticketing world, In particular, consumers resented than $35 billion in overdraft fees. the seemingly mysterious service charges, conve- When legislation took effect in 2010 to curtail this nience charges, and processing charges commonly lucrative revenue stream, many banks brought added on top of ticket prices, and Ticketmaster back an account-keeping fee, which they had abolished years earlier in order to attract customers. Indeed, from 2009 to 2011, the Many of the sectors percentage of large U.S. banks offering free with the worst checking dropped from 96% to 35%. Years customer satisfaction ago shifting the revenue stream from a vis- scores also have the ible checking account fee to a hidden over- draft fee made sense. Customers tended to most complicated welcome free checking and to fail to notice or pricing plans. anticipate the likelihood of incurring the new fee. Now, as banks reinstate account-keeping fees, consumers are responding: From 2010 to 2011, the number of consumers opening accounts at credit unions, where checking is free, has doubled. In contrast to the antagonism such practices cie- ate, consider how transparency helped Shenzhen June 2012 Harvard Business Review 103 FAIR PRICING TO CREATE SHARED VALUE HBR.ORG exacerbated the hostility by hiding these fees until in which IKEA and its customers jointly create and late in the already tedious purchase process. Re- share value and jointly keep prices low. cently, however, the company began disclosing them at the start, a simple move that Ticketmaster reports An Evolving Strategy has increased repeat purchases. Most firms rate poorly on at least several of our prin- IKEA, in contrast, has done a stellar job of manag-ciples for shared-value pricing. If your company is ing expectations, as reflected in the almost spiritual among them, you can either treat your customers loyalty of its customers. Navigating a vast, mazelike like partners in value creation and set prices accord- store, transporting unassembled fumiture, and put- ingly or watch firms that do steal market share and ting it together at home isn't for everyone, but for profits. those who are willing, IKEA makes a promise. On J.C. Penney, in a bid to reverse a long decline, is its website and in its marketing literature, the com- doing the former. As recently as last year, Penney pany explicitly states what a consumer can expect bombarded shoppers with almost 600 promotions, and unfailingly delivers on that promise. IKEA will each one more confusing than the last, all focused on scour the globe for smart ways to make good-looking driving up sales. The message was more "we value furniture, find suppliers who are willing to provide your money than "we value you." Today under a the most suitable materials at low prices, and then new CEO, Ron Johnson, Penney is busily remaking buy in bulk to get deals that allow the company to of- the customer experience, and pricing is central to the fer prices 30% to 50% below competitors'. In return, strategy. Previously, Johnson created the famously customers must be willing to engage with the chal- engaging Apple Store, and that focus is increasingly lenging purchase, transport, and assembly process. apparent at Penney. In a highly publicized move the In this IKEA is unapologetic: You do your part and retailer has introduced "fair and square" pricing, we will do ours. The result is a shopping experience which is meant to be in sync with customers' lives rather than to coerce shoppers into unplanned and often unnecessary purchases. To signal this new transparency, the chain offers only three types of prices-everyday, monthlong, and clearance. And, in a small but symbolic move, all prices end in .00, not in 99. The major U.S. airlines, in contrast, are doing the latter, watching as first Southwest, then JetBlue, and now Virgin America provide for free many of the ame- nities that the majors charge for. It is little wonder CEO CFQ CSG why J.D. Power named those three airlines "2012 Cus- tomer Service Champions" and why each has an in- creasingly loyal following and climbing market share. Time will tell how effective Penney's new pricing strategy is. It could fall short because of poor imple- 09 mentation, underlying business conditions, or other factors. Similarly, the Olympics' pricing scheme will probably experience some glitches. Shared-value pricing is a nascent and evolving strategy, and some experiments will surely fail. But given the funda- mental shifta in consumers' power and expecta tions, customers will have dwindling patience for antagonistic pricing. And considering the benefits to Daveppender be gained by increasing the pool of value in the mar- ketplace and sharing it with customers, any firm that is not evaluating its pricing through a shared-value "Chief Second Guesser. lens should ask whether it can afford not to. HBR Reprint R1206F 104 Harvard Business Review June 2012 DOC CATTOON ONE OTIENTERStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts